Abstract

Laboratory studies of human dietary choice have relied on computerized two-dimensional (2D) images as stimuli, whereas in everyday life, consumers make decisions in the context of real foods that have actual caloric content and afford grasping and consumption. Surprisingly, few studies have compared whether real foods are valued more than 2D images of foods, and in the studies that have, differences in the stimuli and testing conditions could have resulted in inflated bids for the real foods. Moreover, although the caloric content of food images has been shown to influence valuation, no studies to date have investigated whether ‘real food exposure effects’ on valuation reflect greater sensitivity to the caloric content of real foods versus images. Here, we compared willingness-to-pay (WTP) for, and expectations about satiety after consuming, everyday snack foods that were displayed as real foods versus 2D images. Critically, our 2D images were matched closely to the real foods for size, background, illumination, and apparent distance, and trial presentation and stimulus timing were identical across conditions. We used linear mixed effects modeling to determine whether effects of display format were modulated by food preference and the caloric content of the foods. Compared to food images, observers were willing to pay 6.62% more for (Experiment 1) and believed that they would feel more satiated after consuming (Experiment 2), foods displayed as real objects. Moreover, these effects appeared to be consistent across food preference, caloric content, as well as observers’ estimates of the caloric content of the foods. Together, our results confirm that consumers’ perception and valuation of everyday foods is influenced by the format in which they are displayed. Our findings raise important new insights into the factors that shape dietary choice in real-world contexts and highlight potential avenues for improving public health approaches to diet and obesity.

Keywords: Real foods, images, valuation, satiety, caloric density

1 INTRODUCTION

Obesity contributes significantly to the global burden of disease and increases the risk of heart disease, Type II diabetes and cancer (Bean, Stewart, & Olbrisch, 2008; Brownell & Gold, 2012; Klein et al., 2007; Wellman & Friedberg, 2002; Zhang & Wang, 2004). The alarming increase in obesity over the last three decades has been linked to the availability, accessibility and affordability of inexpensive, energy-dense snack foods (Afshin et al., 2017; Drewnowski & Darmon, 2005). Although a large body of research has documented the various visual properties of foods (such as their color, size, shape, and number) that can influence appetite and consumption (Imram, 1999; Wadhera & Capaldi-Phillips, 2014), recent research efforts have focused on understanding the underlying cognitive and neural systems that regulate decision-making and dietary choice (Rangel, 2013; Schultz, 2000). In turn, research outcomes in this domain have formed the foundation for public health initiatives aimed at curbing rising obesity rates. Unfortunately, however, these initiatives appear to have met with little to no measurable success (Drewnowski & Darmon, 2005; Imram, 1999; Marteau, Hollands, & Fletcher, 2012; Neal, Wood, & Quinn, 2006).

One potential reason for inconsistencies between laboratory studies of human decision-making versus the behavior of consumers in the real-world, is that the types of stimuli used in the laboratory do not reflect those consumers typically encounter when they make daily dietary choices (Camerer & Mobbs, 2017; Ledoux, Nguyen, Bakos-Block, & Bordnick, 2013; Medic et al., 2016). In the laboratory, observers are typically required to make decisions about two-dimensional (2D) images of foods that are displayed on a computer monitor (Beaver et al., 2006; Bode, Bennett, Stahl, & Murawski, 2014; Hare, O’Doherty, Camerer, Schultz, & Rangel, 2008; Plassmann, O’Doherty, & Rangel, 2010; Polanía, Krajbich, Grueschow, & Ruff; Rangel, 2013; Tang, Fellows, & Dagher, 2014). In the real-world, however, consumers typically make dietary decisions in the presence of real foods, such as at the fridge, cafeteria, or supermarket.

Real foods differ from their images in a number of respects that could have a critical influence on behavior and neural responses. Perhaps most importantly, real foods (but not their images) have actual caloric content. At a more fundamental level, when viewed with two eyes, real objects have a definite distance, location, and size relative to the observer, whereas for 2D computerized images only the distance to the computer monitor is known. When real objects are perceived to be within reach, they activate dorsal brain networks involved in reaching and grasping, in humans (Gallivan, Cavina-Pratesi, & Culham, 2009; Gallivan, McLean, & Culham, 2011) and monkeys (Iriki, Tanaka, & Iwamura, 1996; Mountcastle, Lynch, Georgopoulos, Sakata, & Acuna, 1975). Similar dorsal motor networks have been shown to be engaged when laboratory animals are confronted with real food rewards (Bruni, Giorgetti, Bonini, & Fogassi, 2015; Platt & Glimcher, 1999; Schultz, Tremblay, & Hollerman, 2000; Sugrue, Corrado, & Newsome, 2004; Volkow, Wang, & Baler, 2011). Although image interaction is becoming increasingly common in the modern world, humans have presumably evolved to perceive and grasp real objects and to consume real foods, not images (Cisek & Kalaska, 2010; Heft, 2013). Moreover, the size of food images in most human decision-making studies has not matched the typical real-world size of the foods, possibly making portion size ambiguous.

Although three-dimensional (3D) stereoscopic images more closely approximate the visual appearance, distance, and size of their real-world counterparts, it is the case that only real objects afford genuine physical interaction and have actual caloric content. Indeed, the physical presence of a food may be a powerful trigger for automatic Pavlovian (Bushong, King, Camerer, & Rangel, 2010; Pavlov, 2010; Rangel, 2013) and habit-based (Lally, van Jaarsveld, Potts, & Wardle, 2010; Neal et al., 2006) decision control systems that may place little if any weight on the long-term health consequences of poor food choices. It is possible, therefore, that studying responses to artificial displays has left important gaps in our understanding of the mechanisms that drive naturalistic decision-making, with detrimental flow-on effects for public health programs and policy.

The extent to which stimulus format influences decision-making has received surprisingly little systematic investigation. Classic early studies conducted at Stanford University by Walter Mischel and colleagues (Mischel, Ebbesen, & Zeiss, 1972; Mischel & Moore, 1973) showed that display format can have a dramatic influence on decision-making behavior in young children. In an initial study, Mischel et al. (1972) measured how long preschool children were able to wait alone in a room for the chance to consume a preferred food reward (i.e., a sweet biscuit). During the delay period, the children sat at a table facing either the preferred (but delayed) reward, a less preferred reward (e.g., a pretzel) that was immediately available, both food rewards, or neither reward. The authors found that if the snack foods were absent from view during the waiting period, the children were able to wait longer for the delayed (preferred) reward than if the snacks were in view. However, in a subsequent follow-up experiment, Mischel and Moore (1973) found that preschool children were able to wait for a preferred delayed reward when the stimuli were displayed as realistic color images (rather than real foods) during the delay period. The authors concluded that real foods have a more powerful influence on young children’s behavior than abstract representations, and they speculated as to whether real food displays would have a less pronounced influence on adult behavior (Mischel & Moore, 1973).

Only a few studies have examined whether the format in which a stimulus is displayed influences valuation in adults (Bushong et al., 2010; Gross, Woelbert, & Strobel, 2015; Müller, 2013). In the first of these studies, Bushong et al. (2010) measured college-aged students’ ‘willingness-to-pay’ (WTP) for a range of appetitive (i.e., desirable) snack foods using a Becker DeGroot Marschak (BDM) bidding task (Becker, DeGroot, & Marschak, 1963). In the main experiment, participants were divided into three separate groups; one group viewed text descriptors of the snacks (e.g., “Snickers bar”), another group viewed the foods in the form of high-resolution colored photographs and the remaining participants viewed the stimuli as real snack foods. Students who viewed the real snacks bid 61% more for the foods than those who viewed the same items as images or text displays –a phenomenon the authors termed the ‘real-exposure effect’ (Bushong et al., 2010). The effect was equally apparent for strongly- and weakly-preferred items. A similar result (albeit a less dramatic 41% increase in WTP) was observed in a follow-up experiment in which students bid on trinkets, instead of snack foods. However, several aspects of Bushong et al. (2010) methodology could have resulted in inflated bids for the real objects. Participants in the text and photograph conditions were tested in parallel in groups of 6–12 at a time, whereas participants in the real object condition were tested one-on-one with the experimenter. The visual appearance of the stimuli and timing of events were also not closely matched across the different viewing conditions. Interestingly, a follow-up experiment revealed that bids for real foods were lower when participants viewed the items behind a transparent barrier that prevented ‘in-the-moment’ access to the foods. However, because parallel bids were not collected from the same observers in the context of image displays (or for real foods without the barrier), it is not possible to determine whether the bid values in the barrier study reflect an effect of display format or a-priori differences in the subjects’ bids for the foods. Müller (2013) showed a 31% increase in observers’ willingness-to-buy foods and objects when the stimuli were displayed as real exemplars versus colored photos. However, Müller’s (2013) images were not matched to the real objects, and the magnitude of the ‘real-exposure effect’ was lower than that reported by Bushong et al. (2010), even though participants were allowed to touch the stimuli during their study –a manipulation that might otherwise have been expected to amplify valuation for the real objects. Finally, using a monetary bidding task similar to Bushong et al. (2010), Gross et al. (2015) reported that WTP for real snack foods was reduced when participants wore a heavy wrist-band at the time of decision-making, compared to when no weights were worn. The effect of weight on value judgments was not observed in a separate group of participants who were exposed to the same weight manipulation, but viewed text displays of the items. Critically, however, the authors did not examine WTP for pictures of the foods. A number of studies indicate that words, which do not have visual properties that indicate manipulability (like pictures), are processed and represented differently to images of objects (Azizian, Watson, Parvaz, & Squires, 2006; Pezdek, Roman, & Sobolik, 1986; Salmon, Matheson, & McMullen, 2014; Schlochtermeier et al., 2013; Seifert, 1997), and may therefore not be expected to show ‘action-’, or ‘effort-related’ effects on valuation.

Finally, as outlined above, one fundamental difference between real foods and their images (as well as between real foods and other types of real objects and artifacts) is that real foods have actual caloric content. Recent behavioral and neuroimaging evidence suggests that valuation increases with caloric density. Using colored images of foods as stimuli, Tang et al. (2014) reported recently that monetary bids for snack foods, as well as neural activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (a brain area involved in computing the value of potential outcomes at the time of choice (Camerer & Mobbs, 2017; Hare et al., 2008; Rangel, 2013), correlated positively with the depicted foods’ caloric density. Surprisingly, however, in Tang et al. (2014) study, observers were poor at estimating the caloric content of the food images and bids did not correlate with observers’ own estimates of the caloric content of the food images. These results raise the intriguing question of whether valuation of real foods might be influenced more by caloric content than 2D images that do not have inherent energy value. If the mechanism for real food exposure effects reflects a sensitivity to the energy content of a food (for example via additional visual, olfactory or auditory cues), and if valuation increases with caloric content (Tang et al., 2014), then we should observe an interaction between display format and measures of caloric richness.

Here, across two experiments, we examined whether the value applied to a food and expectations about satiety after consuming foods, differ as a function of the format in which foods are displayed, as well as their caloric content. In Experiment 1 we measured hungry observers’ WTP for real foods versus high-resolution colored images of the same foods using a BDM task, based on that of (Bushong et al., 2010). Unlike previous studies, we used a within-subjects design in which stimulus timing and environmental conditions were identical for the real object and image displays. Our real object and image stimuli were matched closely for apparent size, distance, viewpoint, and background, and the order of trials in each display format was randomized throughout the experiment. Corresponding ratings were collected from observers with respect to their familiarity and preference for each food, as well as the perceived caloric content of the foods. Importantly, given the nested structure of the data, we used linear mixed effects modeling to evaluate the extent to which display format, preference, caloric content, and estimated calories, influenced WTP. We predicted that monetary bids for the real foods would be greater than their images, even after powerful effects of preference were accounted for in the model. We were particularly interested in whether valuation of the real foods and images would depend on the energy-richness of the foods, as measured either by actual or perceived caloric content. Given that it may be difficult or unnatural to think about food in terms of calories, Experiment 2 examined whether display format influences expectations about how satiating foods would be to consume.

2 EXPERIMENT 1

2.1 Method

2.1.2 Participants

Thirty undergraduate students at the University of Nevada, Reno (16 female, Mean age = 22.14, SD = 5.32) participated in Experiment 1 in exchange for course credit, or $10 payment. Participants also received an allowance of $3 that they could use to bid on the snack foods. Individuals were excluded if they had a history of eating disorders or food-related diseases, dieted in the past year, had any dietary restrictions (such as being vegetarian or vegan), were pregnant, or disliked commercial snack foods. All participants provided informed consent and the experimental protocols were approved by the University of Nevada, Reno Social, Behavioral, and Educational Institutional Review Board.

2.1.3 Stimuli and Apparatus

We compared responses to everyday snacks that were presented either as real foods or high-resolution colored computerized 2D images. We selected 60 popular snack foods (e.g., Cheetos, Snickers bar, M&Ms) that ranged in caloric density (total calories per serving/total grams per serving) from 0.18 to 6.07. The foods were displayed on white paper plates with both the package and some of the food visible (Bushong et al., 2010). The plates were presented on a custom-built manually-operated turn-table (Figure 1A). The turntable, which was 2 m in diameter, was divided into 20 sectors (62 cm depth × 26 cm width), each separated by 24cm vertical dividers. Stimuli on the turntable were viewed through a large 59 cm × 23 cm rectangular aperture, within a 152.5 cm × 127.5 cm vertical partition that was mounted between the subject and the turntable. The viewing aperture prevented more than one stimulus on the turntable from being visible on each trial, but did not interfere with observers’ manual access to the foods.

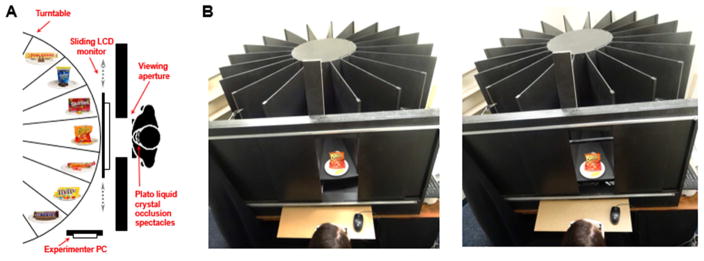

Figure 1. Experimental apparatus and stimuli.

(A) Aerial schematic showing display setup. The stimuli in Experiment 1 were 60 different everyday appetitive snack foods. Half of the snacks were presented to observers as real objects, and the remainder as high-resolution colored 2D computerized images. The real foods and images were presented to observers on a custom-built turntable apparatus. On real food trials, one snack food was visible to the observer on a sector of the turntable. On image trials, the stimuli were displayed on an LCD computer monitor. The monitor, which was mounted to a sliding track behind the viewing aperture, was positioned in front of the turntable on image trials, and retracted to the side of the viewing aperture on real object trials. Observers sat ~50cm from the turntable and all stimuli were within reaching distance. The experimenter, who stood out of participants’ view behind a curtain, controlled manually the stimulus order and display format on upcoming trials. Trial timing and stimulus duration were controlled on all trials using PLATO liquid crystal occlusion spectacles. (B) The images (shown right) were matched closely to the real-foods (shown left) for apparent size, distance, viewpoint, and background.

We generated computerized images of the 60 snack foods by photographing each real food item on the turntable. The stimuli were photographed using a Canon Rebel T2i DSLR camera with constant F-stop and shutter speed. The camera was mounted on a tripod, which was positioned at the approximate height and distance of the participant when looking at the objects from straight ahead. Image size was fine-tuned using Adobe Photoshop so that the resulting displays matched closely the real objects for size, apparent distance, viewing angle, and background (see Figure 1B). The food images were displayed to participants on a 27″ Acer G276HL LCD computer monitor. The monitor was attached to a horizontal sliding track behind the vertical partition. Using the sliding track, the monitor could be moved rapidly in-between the viewing aperture and the turntable, thereby displaying the images (but not the real foods) on image trials (Figure 1B, left panel). The same monitor was used to display the rating scales that participants used to enter their responses on all trials. A black curtain was mounted beside the turntable to prevent participants from seeing the experimenter. A Dell T1700 Intel i7 CPU running Microsoft Windows 7 was positioned behind the curtain, to display to the experimenter information about the food identity and display format on upcoming trials. Stimulus viewing time in both the real object and image conditions were controlled using PLATO liquid crystal occlusion glasses (Milgram, 1987) that alternate between opaque (closed) and transparent (open) states.

2.1.4 Procedure

Participants were asked to refrain from eating three hours prior to the start of the experiment. All testing sessions were conducted in the afternoon between the hours of 1:00 – 7:00 pm. Upon arrival, participants completed a questionnaire to indicate the time at which they had last consumed any food or beverage, how hungry they were (10-point Likert scale), if they were on a diet (Y/N), and how much they enjoyed eating snack foods (10-point Likert scale). All participants were tested individually, one-on-one with the experimenter.

The experiment consisted of four main phases: a Liking-rating task, a Familiarity-rating task, a Bidding task, and a Food Auction (Figure 2A). Participants completed the Familiarity-rating and Liking-rating tasks first, before the main Bidding task and Food Auction. After these four phases were complete, participants completed a paper-and-pencil Caloric Estimation task. For the caloric estimation task, which was completed during the final waiting period, observers made judgments about how many calories they believed were in each of the 60 food items presented during the main experiment. Stimuli for the Caloric Estimation task were presented to observers in the form of text prompts (e.g., “Snickers bar”).

Figure 2. Experimental design.

(A) Timeline of the experiment. (B) Trial sequence for the Liking-rating, Familiarity-rating, and Bidding Tasks. For the Liking-rating Task, observers viewed an image of each snack food for 3 s, and then rated how much they liked the food item on a scale of −7 (strongly disliked) to +7 (strongly liked). In the Familiarity-rating task, observers viewed each food item (3 s) and then rated how familiar they were with the food, on a scale from 0 (not familiar) to 3 (very familiar). Observers entered their ratings by moving an analogue bid bar with a computer mouse. The order in which the Liking and Familiarity Tasks were completed was counterbalanced across observers. Next, participants completed a Bidding Task, in which they indicated their willingness-to-pay (WTP) for the chance to eat the food item after the experiment. On each trial, the PLATO spectacles opened (transparent state) revealing the stimulus (either a real food on the turntable, or an image of a food on the monitor) for 3 s. The PLATO spectacles then closed (opaque state) for a 3s inter-trial interval (ITI). The spectacles then re-opened to reveal the computer monitor displaying an analogue bid bar. Observers entered a bid (between $0 to $3) for the food, before continuing to the next trial. Trials were separated by a 5 s ITI (spectacles closed). After the main bidding task, we conducted a Food Auction to determine whether or the participant purchased a food item, and its price. All participants waited in the laboratory for 30 mins after the experiment, regardless of the outcome of the auction.

2.1.4.1 Liking and Familiarity Rating Tasks

We measured each participants’ likingness for each food item to determine the extent to which food preference influenced bid values (Bushong et al., 2010; Gross et al., 2015; Müller, 2013). On each trial, a high-resolution color photograph of a food item was presented for 3 sec, followed by a rating scale (Figure 2B). During the Liking-rating task, participants were asked “How much do you like ….?”, on a scale of −7 to 7, with zero denoting indifference. Additionally, we included a control task to verify that our sample was comprised of everyday familiar snack foods. In the Familiarity rating task, participants were asked to rate “How familiar are you with ….?”, on a scale of 0 (not very familiar) to 3 (very familiar). In both tasks, responses were entered by clicking with a computer mouse on a sliding analogue bid bar positioned below the text. An integer, corresponding to the desired bid amount, was displayed in a black box below the scale. Trials were self-paced and each trial was initiated via a computer mouse click. The order of stimulus presentation within the Familiarity- and Liking-rating tasks was randomized, and the order of tasks was counterbalanced across observers.

2.1.4.2 Bidding Task

The main experimental task was a BDM bidding task (Becker et al., 1963). The BDM, which is used frequently in studies of decision-making (Bushong et al., 2010; Gross et al., 2015; Johnson, Haubl, & Keinan, 2007; Plassmann et al., 2010), resembles a real-world buying scenario in which a consumer estimates how much money they are willing to pay to purchase a food. At the beginning of the experiment, participants were informed that they would be given an allowance of $3 that they could use to purchase common sweet and salty snack foods displayed during the study. Participants were instructed that they would need to wait in the lab for 30 mins after completing the experiment, regardless of whether or not they purchased a snack. If they purchased a snack food during the study they would be allowed to eat it during the waiting period; no other foods were allowed. Together with the requirement that participants refrain from eating prior to the experiment, these manipulations are typically used in incentivized decision experiments to limit the influence of market prices on bids (since an observer could purchase the same foods with their experimental allowance after the experiment) (Bushong et al., 2010; Gross et al., 2015; Plassmann et al., 2010).

During the Bidding task, participants saw each of the 60 snack foods once, either as a real food or an image. The order in which trials in each display format were presented was randomized within and between observers. White noise was played in the testing room throughout the experiment to mask any sounds generated by the monitor or turntable. Trials in the Bidding task began with the PLATO glasses closed (opaque state). The glasses opened (transparent state) to reveal the food stimulus for 3 sec. On ‘real object’ trials, the monitor was retracted behind the viewing aperture and the real food was visible on the turntable. On image trials, the computer monitor was positioned within the viewing aperture and the food stimulus was displayed on the monitor (Figure 1B).

The LCD glasses then returned to the closed state for a 3 sec inter-stimulus interval (ISI), during which the experimenter ensured that the monitor was positioned within the viewing aperture. The glasses then re-opened and the participant was prompted, via a text display on the monitor, to rate “How much do you bid for …?”, on a scale from $0 to $3. Bids were entered by clicking with a mouse on the analogue bid bar, as described above. Once a bid was entered, the glasses closed for a ~5 sec inter-trial interval (ITI) in which the experimenter positioned the stimulus for the upcoming trial within the viewing aperture. The upcoming trial was initiated by the experimenter. Participants completed 3 practice trials before starting the main Bidding task.

2.1.4.3 Food Auction

After the Bidding task was completed, we conducted a Food Auction. A computer was programmed to select randomly one of the 60 food items shown in the study, along with a random number between $0 – $3, in $0.25c increments. If the participants’ bid was equal to or greater than the computer-generated number, the participant would ‘win’ the item and pay a price equal to the computer’s bid from their $3 allowance. If the participant’s bid was below the computer-generated number, they could not purchase the item, and would keep their $3. For example, if a participant bid $2.30 for an item, and the computer-generated number was $2.25, the participant would purchase the item for $2.25. Participants were advised to refrain from basing their bids on expected retail prices, but rather to construct their bids based on how much they wanted to pay to eat the item at the end of the auction. Participants were informed that the optimal strategy under these conditions was to bid the maximum that they were willing to pay for each food item. This is because the selected bid amount could only influence the chance to purchase the food, but not the selling price. Importantly, to ensure that participants believed that they were spending their own money on the foods (as they would be in real-world purchasing situations), they were advised that any money from the $3 allowance not spent during the study, was theirs to keep (Becker et al., 1963). The entire experiment took ~ 2.5 hours to complete, not including set-up time.

2.1.5 Data Analysis

We were primarily interested in examining the extent to which Display Format influenced WTP in the main Bidding task, and whether any such effects of Display Format were modulated by observers’ preference for the foods as measured by Liking ratings, the actual Caloric Density of the foods, or the estimated number of calories (Estimated Calories) in the foods. Because the data were nested within participants (i.e., each participant contributed responses for real objects and 2D images), it is not appropriate to analyze the data using correlation or regression approaches, both of which assume independence among observations (Snijders, 2011). Therefore, we employed a linear mixed-effects model in which the dependent variable was participants’ bid values for each food item, and Display Format, Liking ratings, Caloric Density, and Estimated Calories were entered as fixed effects in the model, using the restricted maximum likelihood estimation method. The model also included random effects of Participants to account for the variability among responses within each observer. We conducted preliminary t-tests and correlation analyses to compare mean bids versus retail values of the foods using Matlab and SPSS (MathWorks, 1996; SPSS, 2011). The linear mixed effects modeling analysis and estimation of effect size (Cohen’s d) was conducted using SPSS. In line with the assumptions of linear mixed effects modeling (Faraway, 2016), we confirmed that the residuals of the model (i.e., Bids from Experiment 1, and Heaviness Ratings from Experiment 2) were normally distributed.

2.2 Results

Two participants bid incorrectly during the main bidding task. Due to an experimenter error, the first participant enrolled in the study received incomplete task instructions and no practice trials; the observer placed $0.00 bids on 35% of trials and near-zero responses on all remaining trials. The other participant bid $0.00 bids on 90% of trials (despite high Likingness ratings for all items). Consequently, the data from both observers were excluded from further analysis. Mean ratings of the snack foods on the Familiarity rating scale were high (M = 2.43, SD = 0.88), confirming that participants were very familiar with the stimuli included in the study. Because the Familiarity rating task served as a control to ensure that participants recognized all of the food stimuli, these data were not entered into the main modelling analysis. The mean bid for the snacks was $1.14 (SD = .36), which was significantly greater than their typical retail value ($0.94, SD = .57; t(59) = 2.51, p =.015). There was no correlation between bids and retail value for either the real foods (r(58) = 0.055, p = 0.674) or their 2D images (r(58) = −0.012, p = 0.930).

For the linear mixed effects modeling analysis, we first tested the main effects of the four independent variables (Display Format, Caloric Density, Estimated Calories, and Liking ratings) on WTP. The results indicated that bids were influenced by all four independent variables. First, consistent with the findings of previous studies using image displays (Bushong et al., 2010; Hare et al., 2008; Plassmann et al., 2010), there was a strong main effect of Liking on the amount observers bid for the snack foods (F(1, 1655) = 1803.69, p < 0.001). Examination of the slope indicated that observers were predicted to increase their bid by $0.15 on average for one unit increase in Liking-rating, β = 0.15, t(1655) = 42.47, p < 0.001; d = 8.03. There was also a significant main effect of Caloric Density (F(1, 1649) = 6.87, p < 0.01) on WTP. Slope estimates indicated that bids increased by $0.024 on average per one unit increase in caloric density, β = 0.024, t(1649) = 2.62, p < 0.01; d = 0.50. Unlike Tang et al, (2014), however, the main effect of Estimated Calories was also significant (F(1, 1672) = 6.88, p < 0.01), indicating that participants’ own estimations of the number of calories in the foods influenced their bid values. The slope estimation indicated that participants were predicted to increase their bid by $0.009 on average for one unit increase in estimated calories, β = 0.009, t(1671) = 2.62, p < 0.01; d = 0.50. Critically, however, controlling for the effects of Liking, Caloric Density and Estimated Calories on bids, there was also a significant main effect of Display Format (F(1, 1645) = 7.99, p < 0.01, d = 0.53), in which average bid for real foods (M = $1.16, SD = 0.89) was higher than that of images (M = $1.09, SD = 0.87), an increase in WTP of 6.62%. The effect of Display Format was strikingly consistent across observers, with 20 out of 28 participants showing the predicted effect.

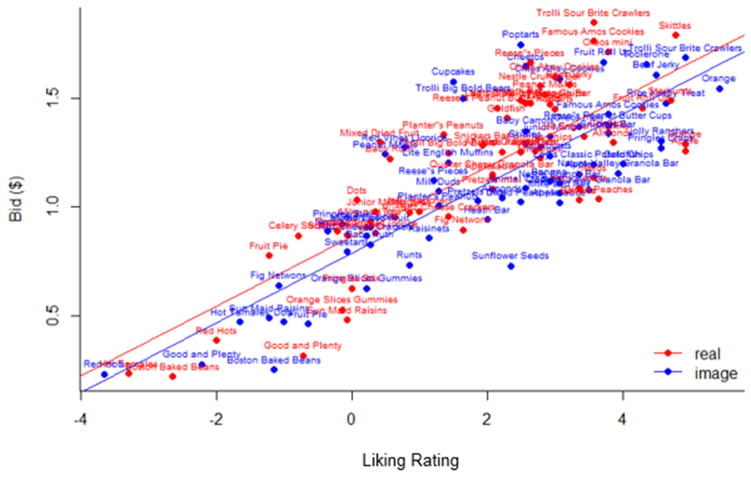

Next, we examined whether the effect of Display Format varied as a function of Liking Ratings, Caloric Density, or Estimated Calories, by searching for two-way interactions between Display Format and each of these factors, respectively, in the linear mixed effects model. For illustrative purposes, Figure 3 shows mean bids for each snack food item plotted as a function of Liking ratings, separately for foods that were displayed as real objects (shown in red) or 2D images (shown in blue). As is evident from Figure 3, the effect of Display Format on bids was constant across Liking ratings (F(1, 1644) = 0.025, p = 0.88). Similarly, neither the interaction between Display Format and Caloric Density (F(1, 1643) = 2.54, p = 0.11) (Figure 4), nor the interaction between Display Format and Estimated Calories (F(1,1643) = 0.11, p = 0.74), was significant. We then compared the model that included only the main effects of the four independent variables, versus a model that included the four main effects and their two-way interactions (Display Format × Caloric Density; Display Format × Estimated Calories), based on the maximum likelihood estimation method. This analysis revealed no significant difference between the two models (χ2(2)=2.43, p =0.30), further confirming the absence of two-way interactions in the previous analyses. Tests of other higher-order models revealed no 3-way or 4-way interactions between any of the factors (Fs ≤ 1.46, ps ≥ 0.23).

Figure 3.

Scatter plots, with lines of best fit, show a strong positive association between WTP and Likingness ratings, as well as a main effect of Display Format in which bids for real foods were greater than matched food images. Mean bid values ($) for the foods are displayed separately for the real foods (red) and 2D images (blue). Each data point represents the group average bid for each food item, separately for foods in each display format.

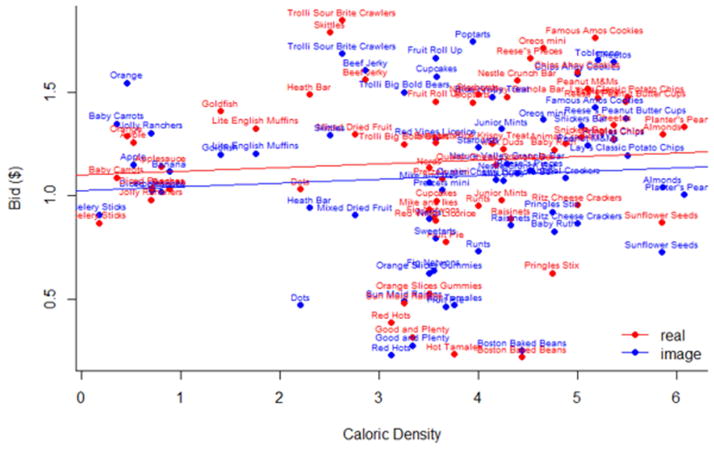

Figure 4.

Scatter plots, with lines of best fit, show a positive association between WTP and Caloric Density, as well as a main effect of Display Format in which bids for real foods were greater than food images. Mean bid values ($) for the foods are displayed separately for the real foods (red) and 2D images (blue). Each data point represents a group average for each snack food (labeled above).

Finally, a follow-up analysis using Estimated Calories as the dependent variable, and Liking, Caloric Density, and Display Format, as independent variables (with Participants as the random factor), revealed a significant main effect of actual Caloric Density on Estimated Calories (F (1, 1649) = 129.64, p < 0.001), but no main effects of either Liking or Display Format (Fs ≤ 1.46, ps ≥ 0.23).

3 EXPERIMENT 2

The results of Experiment 1 confirm that the format in which snack foods are displayed has a significant influence on willingness-to-pay. Monetary bids for real foods were significantly greater than bids for matched 2D images of the same foods. The effect of display format was constant across preference ratings (i.e., equally apparent for preferred and non-preferred foods), as well as across actual caloric density, and observers’ estimates of the number of calories in the foods. It could be the case, however, that most individuals are not accustomed to thinking about foods in terms of numbers of calories. This leaves open the question of whether the effect of display format on valuation may be more heavily influenced by the energy-richness of the foods if observers are asked to make more intuitive judgements about foods, such as their effect on satiety –the feeling of being full. Given that the primary aim of Experiment 1 was to examine whether effects of display format on valuation, as reported by Bushong et al., (2010), are apparent under tightly-controlled experimental conditions, we did not modify the bidding procedure. However, it could be the case that caloric estimates were not influenced by display format because participants made their estimates of caloric content after the main study in response to text prompts, rather than while they were viewing the stimuli during the bidding phase. Therefore, in Experiment 2 we examined whether display format and actual caloric content influenced observers’ ratings of satiety when observers performed satiety ratings while viewing the real objects and 2D images.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Sixteen students (10 female, Mean age = 26.35, SD = 7.18) participated in the study for a $5 payment. The exclusion criteria and informed consent procedures for participants were identical to those described in Experiment 1.

3.1.2 Stimuli and Apparatus

The stimuli for Experiment 2 were 20 snack foods, and their matched 2D images, that were used in Experiment 1, whose caloric density ranged from .18 to 5.48. All other aspects of the stimuli and apparatus were identical to Experiment 1, except that stimulus viewing time was unlimited and so participants did not wear the Plato glasses during the experiment.

3.1.3 Procedure and Data Analysis

The participants’ task was to rate how ‘satiating’, or filling, a range of different snack foods would be to consume, on a scale from 0 (light) to 10 (heavy). In contrast to Experiment 1, each participant saw the items as both a real food, and as a matched 2D image. The stimuli were presented on the turntable apparatus (Figure 1a, b). Trials in each Display Format (20 real foods, 20 images) were presented in separate blocks. The order of items within each block was randomized, and the order of blocks was counterbalanced across observers. Each trial began with a computer mouse click. On real object trials the experimenter retracted the monitor to reveal a real food item on the turntable; on image trials, a 2D food image appeared on the computer monitor. Participants made their responses by drawing a vertical line on a horizontal scale of 20 cm in length, with 1cm and 1mm major and minor tick-marks, respectively. All participants were tested individually. The experiment took ~30–45 minutes to complete.

As in Experiment 1, we employed a linear mixed-effects model to account for the multilevel structure of the data. In the model, participants’ estimates of satiety for each food item in the real or image conditions constituted the dependent variable. The model included fixed effects of Display Format, actual Caloric Density, and the interaction between these two factors. The model also included random effects of Participant and food Items (since there were repeated observations under each of these factors that were entered into the analysis). The linear mixed effects modeling analysis and estimation of effect size (Cohen’s d) was conducted using SPSS.

3.2 Results

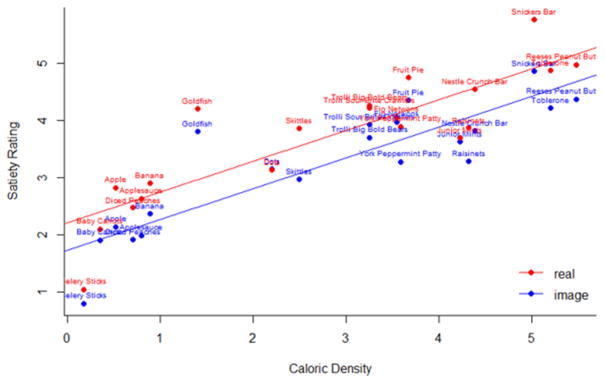

We first tested the main effects of the two independent variables, Display Format and Caloric Density, on observers’ satiety ratings. As expected, there was a strong main effect of Caloric Density (F(1, 303) = 129.07, p < 0.001). Slope estimations indicated that participants were predicted to increase their estimation of satiety by 0.55 units on average per one unit increase in actual caloric density (β = 0.55, t(303) = 10.51, p < 0.001; d = 2.63). In line with the results of Experiment 1, there was also a significant main effect of Display Format on satiety ratings (F(1, 318) = 6.55, p = 0.01), in which the real foods elicited higher average satiety ratings (M = 3.70, SD = 2.29) than 2D images (M = 3.22, SD = 2.15), d = 0.64. For illustrative purposes, Figure 5 shows mean satiety ratings for each snack food plotted as a function of actual Caloric Density, separately for foods that were viewed as real objects (shown in red) or 2D images (shown in blue). As is evident from Figure 5, despite the strong main effect of Display Format and Caloric Density on satiety ratings, there was no interaction between these two factors (F(1, 318) = 0.51, p = 0.48).

Figure 5.

Scatter plots (with lines of best fit) show a strong positive association between observers’ satiety ratings and Caloric Density, and a main effect of Display Format in which satiety estimates were higher for real foods versus food images. Stimuli in Experiment 2 were presented to observers both as real foods, and as matched 2D images of the same items. On each trial, participants rated how satiating (or ‘filling’) each food would be to eat, on a scale from 0 (light) to 10 (heavy). Mean ratings of the foods are displayed separately for the real foods (red) and 2D images (blue). Each data point represents a group average for each snack food (labeled above). There was no interaction between Caloric Density and Display Format on satiety ratings.

4 DISCUSSION

Current knowledge of the cognitive and neural systems that regulate human decision-making is based almost exclusively on studies that have used artificial stimuli in the form of computerized 2D images or text displays. Given that ultimately we aim to understand the processes that unfold in real-world scenarios it is important to determine how, and why, behavior might differ when observers view naturalistic stimuli versus their representations. In the current study, we examined whether observers’ WTP for common snack foods and their expectations about how filling foods would be to eat, depend on the format in which the foods were displayed. In the first experiment, healthy university students participated in a BDM auction in which they placed monetary bids on a range of appetitive snack foods. The foods were presented to observers either as real objects or matched high-resolution 2D colored images. Prior to the auction, participants rated their familiarity with, and preference for, each of the foods. After the experiment, participants estimated how many calories were in each of the foods presented during the auction. We used mixed-effects linear modeling of the multivariate data to determine the extent to which monetary bids for the foods depended on display format, preference ratings, actual caloric density, and participants’ estimates of the number of calories in the foods, as well as whether there were any interactions between each of these factors. As expected, a priori preference for the foods had a strong influence on monetary bids, as in previous studies (Bushong et al., 2010; Hare et al., 2008; Plassmann et al., 2010). Bids for the foods also increased as the actual caloric density, and participants’ estimates of the total number of calories in the foods, increased. Critically, despite the powerful effects of preference and of caloric content on valuation, bids were also influenced by the format in which the foods were viewed: WTP was significantly increased for items displayed as real foods versus 2D images. The effect of display format on WTP was apparent even though participants knew that they would receive the same (real) food reward at the end of the experiment irrespective of how the stimuli appeared during the bidding task. There were no other higher-order interactions between each of these factors in their effect on bids.

Working with naturalistic stimuli under controlled laboratory conditions presents a number of practical challenges to the researcher. As such, very few studies to date have examined directly whether the value applied to 2D images of foods is equivalent to their real-world counterparts, and no studies to date have controlled adequately for differences in the appearance and timing of stimuli across display formats, or accounted for other factors that could modulate valuation (Bushong et al., 2010; Müller, 2013), perception, or other weight-related outcomes (Boswell & Kober, 2016; Lambert, Neal, Noyes, Parker, & Worrel, 1991). Here, using a BDM bidding task comparable to that of Bushong et al. (2010), but in which tight experimental controls were placed on the stimuli, trial timing, and testing environment, we found that observers were nevertheless willing to pay more for real foods versus their matched 2D images. This effect is unlikely to reflect inflated bids for the real foods due to differences in the way the stimuli were presented between the real food and image conditions (Bushong et al., 2010; Müller, 2013). Our 2D images were matched closely to the real foods for illumination, size, background, and viewing angle. Stimulus viewing time was matched on all trials using computer-controlled glasses and the order of trials in each display format was randomized throughout the testing session. We tested all participants one-on-one with the experimenter to rule out the possibility that differences in environmental conditions could differentially influence bids across conditions. Our within-subjects design minimized potential fluctuations in bids between conditions due to between-subject differences in a priori WTP. We also confirmed that all participants were highly familiar with all items, differences in bids across display formats were not attributable to food preference, and variability in bids between observers was accounted for in the estimation of main effects. Together, the results of Experiment 1 demonstrate the presence of a ‘real-exposure effect’ on food valuation (Bushong et al., 2010; Müller, 2013) that amounts to a 6.62% amplification in WTP. Our strict matching of stimulus characteristics between the different display formats may have caused strong associations between the 2D images and real foods, more so than in designs where participants only see one display type, or when stimulus characteristics are not closely matched. It will therefore be important for future studies to determine whether the magnitude of the real exposure effect is increased when matched stimuli are presented in the context of between-participant designs.

We were particularly interested in whether the caloric content of the stimuli would differentially influence valuation. A potential relationship between the format in which foods are displayed and their caloric content is important to consider because it could (a) provide critical insights into the mechanism for real food exposure effects, and (b) help to determine ways in which real-world environments could be manipulated to promote healthier eating and reduce obesity. In line with Tang et al. (2014), the results of Experiment 1 indicated that bids were influenced strongly by the actual caloric density of the foods. Unlike Tang et al. (2014), we also found that observers’ own estimates of the caloric content of the foods were related to bids. Interestingly, however, the effect of caloric content on bids did not appear to depend on the format in which the foods were displayed. Put differently, the amplification in WTP for real foods is equivalent for an apple (with few calories) as it is for a chocolate bar (which is high in calories). If the mechanism for the real food exposure effect on valuation reflects the availability of additional cues to the energy content of real foods versus images, and given that valuation increases with actual and perceived caloric content, then we would expect to have observed an interaction between display format and caloric measures (which was not the case).

The energy content of a food may, however, have a more powerful influence on display format effects if observers make ecologically-relevant judgments about foods, such as how filling they would be to eat (i.e., anticipated satiety), rather than estimates based on numbers of calories. Effects related to energy content may also be more apparent if observers are probed about satiety at the time of stimulus exposure, rather than after the experiment in response to a text-display. Therefore, in Experiment 2 we asked participants to rate how satiated they would feel if they were to consume each food item, both when the foods were presented as real objects and as 2D images. As expected, participants rated that they would feel more satiated if they ate foods of higher caloric density –suggesting that they were sensitive to the energy content of the foods (Almiron-Roig, Solis-Trapala, Dodd, & Jebb, 2013; Brunstrom, Shakeshaft, & Scott-Samuel, 2008; Carels, Konrad, & Harper, 2007; Keenan, Brunstrom, & Ferriday, 2015). Strikingly, participants also believed that they would feel more full after eating a food when they viewed it as a real object than as a matched 2D image of the very same item. Importantly, however, this effect of display format on satiety ratings was comparable for low- and high-calorie foods (similar to Experiment 1 using WTP as the dependent measure). Our data do not, therefore, lend support to the idea that the underlying mechanism for the real food exposure effect is related to caloric content. This conclusion is supported by previous findings that an amplification in WTP is apparent not only in the context of foods, but also with inedible trinkets (Bushong et al., 2010). The observation that the real exposure effect was relatively constant across variations in caloric content and food preference suggests that these factors are weighted similarly during dietary choice, regardless of display format. It is also possible, however, that the lack of an interaction between these factors reflects insufficient power to detect higher-order effects in the context of our linear mixed effects model. Future studies with larger sample sizes may be necessary to reveal more subtle relationships of this nature.

The considerations outlined above raise new questions about the underlying mechanism for the real-exposure effects that we observed in the context of food perception and decisions. One possibility is that observers are aware that real foods decay (whereas images of foods do not), which may elicit a sense of time pressure that is not present in the context of 2D images. We did not ask participants to rate the perceived longevity of the stimuli and so this might be an interesting factor to investigate in future studies. Alternatively, our results could also be interpreted from the perspective of behavioral learning theory. Current models of decision-making posit that behavior is influenced by different control systems that compete with one another, based on whether a behavior is motivated by the stimulus or a particular goal outcome (O’Doherty, Cockburn, & Pauli, 2017). In behavioral learning theory, stimulus-driven control refers to behaviors that are deployed rapidly and automatically in response to environmental cues, irrespective of the observer’s goals or expected outcomes (Balleine, 2005; O’Doherty et al., 2017). Examples of stimulus-driven controllers are reflexes (such as salivation in response to the presence of food), and habits that are established on the basis of stimulus-action associations (such as seeking food in cue-dependent locations that are associated with the receipt of previous rewards (Smith, Virkud, Deisseroth, & Graybiel, 2012). Conversely, goal-directed control refers to flexible behaviors that take into account the long term consequences of actions. Some have argued that, compared to other types of decisions, dietary choices may be unique in that they are influenced strongly by stimulus-driven controllers (Rangel, 2013). It is reasonable to expect that because real foods are a meaningful, biologically-potent stimulus (i.e., an ‘unconditioned stimulus’) they are more powerful triggers of automatic controllers than images, which are not associated strongly with the presence of real food (Balleine, 2005; Balleine, Daw, & O’Doherty, 2008; Bushong et al., 2010).

In contrast to models of decision-making that emphasize the serial progression of information processing from perceptual and cognitive stages to motor outputs (Clithero & Rangel, 2014; Kable & Glimcher, 2009; Padoa-Schioppa, 2011), recent evidence suggests that sensorimotor networks that are involved in generating a potential motor response to a stimulus are activated very rapidly after stimulus onset and can influence the early stages of decision-making (Harris & Lim, 2016). Indeed, a growing body of evidence supports the notion that decisions are represented within the same sensorimotor circuits as those responsible for planning and executing the associated actions (Cisek, 2007; Cisek & Kalaska, 2005, 2010). For example, objects within (but not outside of) reach activate dorsal brain areas involved in reaching and grasping, regardless of whether or not a grasp is overtly planned or executed (Gallivan et al., 2009; Gallivan et al., 2011). We did not ask participants to rate the graspability of the food stimuli in the context of our within-subjects design. Although direct manipulations of affordances for action, such as graspability, have not been conducted in human observers in the context of food decisions, non-human primates have difficulty inhibiting a gasping action towards a proximal food stimulus, but not a distal one (Junghans, Sterck, Overduin de Vries, Evers, & De Ridder, 2016). The notion that real-exposure effects on decision-making may be linked with the potential for action with a stimulus (rather than lower-level stereo differences) is supported by recent findings that real snack foods elicit significantly greater self-reported craving (Ledoux et al., 2013) and affective responses (Gorini, Griez, Petrova, & Riva, 2010) than do 3D immersive virtual reality displays of snack foods.

More broadly, our findings of increased WTP and expectations about satiety for real foods (versus their images), complement other studies showing that real objects can have unique influences on brain responses and behavior. Using fMRI, Snow et al. (2011) found that whereas repeated images of objects elicit repetition-suppression, the same pattern was reduced, if not absent, for matched real-world exemplars, suggesting that the brain processes real objects differently to images. Differences between real objects versus images have also been reported in a range of behavioral measures. For example, preferences for real objects over images are apparent in eye movement patterns in young children as early as 7 months of age (Gerhard, Culham, & Schwarzer, 2016), as well as in non-human primates (Mustafar, De Luna, & Rainer, 2015). Patients with visual form agnosia who have severe deficits in identifying objects depicted in photographs and line-drawings show striking improvements in recognition when they are presented with real-world objects (Chainay & Humphreys, 2001; Humphrey, Goodale, Jakobson, & Servos, 1994). Similarly, real objects are more memorable than colored photographs or line drawings of the very same items (Snow, Skiba, Coleman, & Berryhill, 2014). We have also shown recently, using a flanker interference paradigm, that real objects capture attention more than both 2D and three-dimensional (3D) stereoscopic images of the same objects, suggesting that the unique effect of real objects (versus images) on responses is not merely attributable to richer visual information about the depth structure, size, or distance of the objects (Gomez, Skiba, & Snow, in press). Critically, however, the effects of real objects on attention disappeared when the stimuli were positioned out of reach of the observer, and when they were placed behind a transparent barrier that disrupted the potential for in-the-moment interaction with the objects (Gomez et al., in press). Together, these behavioral and neuroimaging findings raise the question of whether or not the underlying mechanisms that drive real-exposure effects in the context of dietary choice are analogous to those that drive the effects of real objects in the domains of eye-movements, perception, memory and attention.

The results of our experiments, together with related findings in previous studies (Bushong et al., 2010; Müller, 2013), contrast with a recent meta-analysis by Boswell and Kober (2016) that assessed the predictive effects of food cue reactivity and craving on eating and weight-related outcomes. Boswell and Kober (2016) reported that across 49 studies, visual food cues in the form of pictures or videos were associated with a similar effect size as exposure to real foods (and both of these measures elicited stronger effect sizes than exposure to olfactory cues). Boswell and Kober (2016) did not include studies that tested the effects of display format on other outcome measures, such as WTP. Although the effect of display format on WTP in our controlled study (6.62%) was smaller than that reported by Bushong et al., (2010) (61%), the influence of display format on bids in Experiment 1, and on estimated satiety in Experiment 2, nevertheless reflected medium effect sizes. Only one of the studies that contributed to Boswell and Kober’s, (2016) analysis compared directly responses to real foods versus images (Lambert et al., 1991), and little if any information was provided in Lambert et al.’s (1991) study about the nature of the image stimuli or whether they were similar in size, distance, or other important respects to the real objects. It will be important for future studies to determine the extent to which proximity to real food influences other real-world outcome measures, such as consumption and weight change (Medic et al., 2016), as well as whether or not the effects differ across sex, socio-economic status, dieters versus non-dieters, level of self-control or executive function (e.g., Hunter, Hollands, Couturier, & Marteau, 2016; Medic et al., 2016). A reliable 6.62% increase in WTP for real items may indeed have large-scale implications for marketing and product displays (Bushong et al., 2010).

4.1 Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate for the first time a reliable ‘real-exposure effect’ on both willingness-to-pay, and expectations about satiety, for snack foods. The results provide a critical extension to previous studies investigating the effect of display format on decision-making behavior in adults (Bushong et al., 2010; Müller, 2013) and children (Mischel et al., 1972; Mischel & Moore, 1973). Our stimuli and design rule out a number of competing explanations for real food exposure effects, perhaps most importantly the possibility that bids for real foods simply reflect differences in the environmental context or stimulus presentation and timing. Our results suggest that real-exposure effects on food decisions operate independently of other factors that drive valuation, such as food preference and caloric density, although future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to determine whether there may be meaningful relationships between these factors. Together with previous studies (Bushong et al., 2010; Gross et al., 2015; Müller, 2013; O’Connor, Meade, Carter, Rossiter, & Hester, 2014), the results have translational implications that could inform public health approaches to diet and obesity (Drewnowski & Darmon, 2005; Marteau et al., 2012; Neal et al., 2006). Specifically, we predict that that if proximity to real tangible foods has a powerful influence on dietary decisions and expectations about satiety, changes in the way foods are positioned in cafeterias and other food outlets, such as limiting the accessibility of high-calorie foods, or making low-calorie healthy foods easier to reach, should have a measurable influence on buyer behavior and long-term health outcomes (Hunter et al., 2016).

We examined effect of display format and caloric content on valuation and satiety

We implemented tight controls over stimulus presentation and timing

Real foods were perceived as being more valuable and more satiating than images

Effects of display format were constant across preference and caloric content

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was supported by a grant to J.C. Snow from the Clinical Translational Research Infrastructure Network [grant number 17-746Q-UNR-PG53-00]. The work was also supported by grants to J.C. Snow from the National Science Foundation (NSF) [grant number 1632849], and the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01EY026701. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the CTR-IN, NSF or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, … Murray CJL. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(1):13–27. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almiron-Roig E, Solis-Trapala I, Dodd J, Jebb SA. Estimating food portions. Influence of unit number, meal type and energy density. Appetite. 2013;71:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizian A, Watson TD, Parvaz MA, Squires NK. Time course of processes underlying picture and word evaluation: An event-related potential approach. Brain Topography. 2006;18(3):213–222. doi: 10.1007/s10548-006-0270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW. Neural bases of food-seeking: Affect, arousal and reward in corticostriatolimbic circuits. Physiology and Behavior. 2005;86(5):717–730. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Daw ND, O’Doherty JP. Multiple forms of value learning and the function of dopamine. Neuroeconomics: Decision Making and the Brain. 2008;36:7–385. [Google Scholar]

- Bean MK, Stewart K, Olbrisch ME. Obesity in America: Implications for clinical and health psychologists. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2008;15(3):214–224. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver JD, Lawrence AD, van Ditzhuijzen J, Davis MH, Woods A, Calder AJ. Individual differences in reward drive predict neural responses to images of food. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(19):5160–5166. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0350-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GM, DeGroot MH, Marschak J. Stochastic models of choice behavior. Behavioral Science. 1963;8(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bode S, Bennett D, Stahl J, Murawski C. Distributed patterns of event-related potentials predict subsequent ratings of abstract stimulus attributes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e109070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell RG, Kober H. Food cue reactivity and craving predict eating and weight gain: A meta-analytic review. Obesity Reviews. 2016;17(2):159–177. doi: 10.1111/obr.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Gold MS. Food and addiction: A comprehensive handbook. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bruni S, Giorgetti V, Bonini L, Fogassi L. Processing and integration of contextual information in monkey ventrolateral prefrontal neurons during selection and execution of goal-directed manipulative actions. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35(34):11877–11890. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.1938-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunstrom JM, Shakeshaft NG, Scott-Samuel NE. Measuring ‘expected satiety’ in a range of common foods using a method of constant stimuli. Appetite. 2008;51(3):604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushong B, King LM, Camerer CF, Rangel A. Pavlovian processes in consumer choice: The physical presence of a good increases willingness-to-pay. The American Economic Review. 2010;100(4):1556–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Camerer C, Mobbs D. Differences in behavior and brain activity during hypothetical and real choices. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2017;21(1):46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carels RA, Konrad K, Harper J. Individual differences in food perceptions and calorie estimation: An examination of dieting status, weight, and gender. Appetite. 2007;49(2):450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chainay H, Humphreys GW. The real-object advantage in agnosia: Evidence for a role of surface and depth information in object recognition. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2001;18(2):175–191. doi: 10.1080/02643290042000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P. Cortical mechanisms of action selection: The affordance competition hypothesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 2007;362(1485):1585–1599. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P, Kalaska JF. Neural correlates of reaching decisions in dorsal premotor cortex: Specification of multiple direction choices and final selection of action. Neuron. 2005;45(5):801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P, Kalaska JF. Neural mechanisms for interacting with a world full of action choices. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2010;33:269–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clithero JA, Rangel A. Informatic parcellation of the network involved in the computation of subjective value. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2014;9(9):1289–1302. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Darmon N. Food choices and diet costs: An economic analysis. The Journal of Nutrition. 2005;135(4):900–904. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraway JJ. Extending the linear model with R: Generalized linear, mixed effects and nonparametric regression models. CRC Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan JP, Cavina-Pratesi C, Culham JC. Is that within reach? fMRI reveals that the human superior parieto-occipital cortex encodes objects reachable by the hand. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(14):4381–4391. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0377-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan JP, McLean A, Culham JC. Neuroimaging reveals enhanced activation in a reach-selective brain area for objects located within participants’ typical hand workspaces. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(13):3710–3721. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard TM, Culham JC, Schwarzer G. Distinct visual processing of real objects and pictures of those objects in 7- to 9-month-old infants. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7:827. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MA, Skiba RM, Snow JC. Graspable objects grab attention more than images. Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/0956797617730599. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorini A, Griez E, Petrova A, Riva G. Assessment of the emotional responses produced by exposure to real food, virtual food and photographs of food in patients affected by eating disorders. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2010;9:30. doi: 10.1186/1744-859x-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Woelbert E, Strobel M. The fox and the grapes-how physical constraints affect value based decision making. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0127619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, O’Doherty J, Camerer CF, Schultz W, Rangel A. Dissociating the role of the orbitofrontal cortex and the striatum in the computation of goal values and prediction errors. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(22):5623–5630. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.1309-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Lim SL. Temporal dynamics of sensorimotor networks in effort-based cost–benefit valuation: Early emergence and late net value integration. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36(27):7167–7183. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.4016-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heft H. Affordances. In: Runehov ALC, Oviedo L, editors. Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2013. pp. 32–32. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey GK, Goodale MA, Jakobson LS, Servos P. The role of surface information in object recognition: Studies of a visual form agnosic and normal subjects. Perception. 1994;23(12):1457–1481. doi: 10.1068/p231457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JA, Hollands GJ, Couturier DL, Marteau TM. Impact of altering proximity on snack food intake in individuals with high and low executive function: Study protocol. BioMed Central Public Health. 2016;16(1):504. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3184-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imram N. The role of visual cues in consumer perception and acceptance of a food product. Nutrition & Food Science. 1999;99(5):224–230. doi: 10.1108/00346659910277650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iriki A, Tanaka M, Iwamura Y. Attention-induced neuronal activity in the monkey somatosensory cortex revealed by pupillometrics. Neuroscience Research. 1996;25(2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(96)01043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EJ, Haubl G, Keinan A. Aspects of endowment: A query theory of value construction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2007;33(3):461–474. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junghans AF, Sterck EHM, Overduin de Vries A, Evers C, De Ridder DTD. Defying food – How distance determines monkeys’ ability to inhibit reaching for food. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7(158) doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JW, Glimcher PW. The neurobiology of decision: Consensus and controversy. Neuron. 2009;63(6):733–745. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan GS, Brunstrom JM, Ferriday D. Effects of meal variety on expected satiation: Evidence for a ‘perceived volume’ heuristic. Appetite. 2015;89:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Kelley DE, Leibel RL, Nonas C, Kahn R. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: A consensus statement from shaping America’s health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Obesity. 2007;15(5):1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally P, van Jaarsveld CHM, Potts HWW, Wardle J. How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;40(6):998–1009. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert KG, Neal T, Noyes J, Parker C, Worrel P. Food-related stimuli increase desire to eat in hungry and satiated human subjects. Current Psychology. 1991;10(4):297–303. doi: 10.1007/bf02686902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux T, Nguyen AS, Bakos-Block C, Bordnick P. Using virtual reality to study food cravings. Appetite. 2013;71:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM, Hollands GJ, Fletcher PC. Changing human behavior to prevent disease: The importance of targeting automatic processes. Science. 2012;337(6101):1492–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1226918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks I. MATLAB: the language of technical computing: computation, visualization, programming: installation guide for UNIX version 5. Natwick: Math Works Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Medic N, Ziauddeen H, Forwood SE, Davies KM, Ahern AL, Jebb SA, … Fletcher PC. The presence of real food usurps hypothetical health value judgment in overweight people. eNeuro. 2016;3(2) doi: 10.1523/eneuro.0025-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram P. A spectacle-mounted liquid-crystal tachistoscope. Behavior Research Methods. 1987;19(5):449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Ebbesen EB, Zeiss AR. Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1972;21(2):204–218. doi: 10.1037/h0032198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Moore B. Effects of attention to symbolically presented rewards on self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;28(2):172–179. doi: 10.1037/h0035716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle VB, Lynch JC, Georgopoulos A, Sakata H, Acuna C. Posterior parietal association cortex of the monkey: Command functions for operations within extrapersonal space. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1975;38(4):871–908. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H. The real-exposure effect revisited — How purchase rates vary under pictorial vs. real item presentations when consumers are allowed to use their tactile sense. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2013;30(3):304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2013.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafar F, De Luna P, Rainer G. Enhanced visual exploration for real objects compared to pictures during free viewing in the macaque monkey. Behavioural Processes. 2015;118:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DT, Wood W, Quinn JM. Habits: A repeat performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(4):198–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DA, Meade B, Carter O, Rossiter S, Hester R. Behavioral sensitivity to reward is reduced for far objects. Psychological Science. 2014;25(1):271–277. doi: 10.1177/0956797613503663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JP, Cockburn J, Pauli WM. Learning, reward, and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology. 2017;68:73–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padoa-Schioppa C. Neurobiology of economic choice: A good-based model. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2011;34:333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov PI. Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Annals of Neurosciences. 2010;17(3):136–141. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972-7531.1017309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezdek K, Roman Z, Sobolik KG. Spatial memory for objects and words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1986;12(4):530. [Google Scholar]

- Plassmann H, O’Doherty JP, Rangel A. Appetitive and aversive goal values are encoded in the medial orbitofrontal cortex at the time of decision making. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(32):10799–10808. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0788-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt ML, Glimcher PW. Neural correlates of decision variables in parietal cortex. Nature. 1999;400(6741):233–238. doi: 10.1038/22268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanía R, Krajbich I, Grueschow M, Ruff Christian C. Neural oscillations and synchronization differentially support evidence accumulation in perceptual and value-based decision making. Neuron. 82(3):709–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel A. Regulation of dietary choice by the decision-making circuitry. Nature Neuroscience. 2013;16(12):1717–1724. doi: 10.1038/nn.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon JP, Matheson HE, McMullen PA. Photographs of manipulable objects are named more quickly than the same objects depicted as line-drawings: Evidence that photographs engage embodiment more than line-drawings. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:1187. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlochtermeier LH, Kuchinke L, Pehrs C, Urton K, Kappelhoff H, Jacobs AM. Emotional picture and word processing: An FMRI study on effects of stimulus complexity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e55619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg T, Bakkour A, Hover AM, Mumford JA, Nagar L, Perez J, Poldrack RA. Changing value through cued approach: An automatic mechanism of behavior change. Nature Neuroscience. 2014;17(4):625–630. doi: 10.1038/nn.3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Multiple reward signals in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2000;1(3):199–207. doi: 10.1038/35044563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Tremblay L, Hollerman JR. Reward processing in primate orbitofrontal cortex and basal ganglia. Cerebral Cortex. 2000;10(3):272–284. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert LS. Activating representations in permanent memory: Different benefits for pictures and words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1997;23(5):11106–11121. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.5.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KS, Virkud A, Deisseroth K, Graybiel AM. Reversible online control of habitual behavior by optogenetic perturbation of medial prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(46):18932–18937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216264109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB. Multilevel Analysis. In: Lovric M, editor. International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2011. pp. 879–882. [Google Scholar]

- Snow JC, Pettypiece CE, McAdam TD, McLean AD, Stroman PW, Goodale MA, Culham JC. Bringing the real world into the fMRI scanner: Repetition effects for pictures versus real objects. Scientific Reports. 2011;1:130. doi: 10.1038/srep00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow JC, Skiba RM, Coleman TL, Berryhill ME. Real-world objects are more memorable than photographs of objects. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014;8:837. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS, I. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version Version 20.0) Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2011. [Google Scholar]