Abstract

Synthetic cathinones, frequently referred to as “bath salts”, have significant abuse potential, and recent evidence suggests that these novel psychoactive substances can also produce cognitive deficits as well as cytotoxic effects. However, most of these latter findings have been obtained either using high concentrations in vitro or following non-contingent high dose administration in vivo. The present study utilized a model of long-term voluntary binge-like self-administration to determine potential detrimental effects of synthetic cathinones on cognitive function and their known underlying neural circuits, collectively referred to as neurocognitive dysfunction. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were allowed to self-administer the cocaine-like synthetic cathinone 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV, 0.03 mg/kg/infusion i.v.) in 96-hr sessions, or saline as a control. A total of five 96-hr sessions were conducted, each separated by 3 days of abstinence in the home cage. Three weeks following the last 96-hr session, animals underwent assessment of cognitive function using spatial object recognition (SOR) and novel object recognition (NOR) tasks, after which brains were harvested and assessed for neurodegeneration using FluoroJade C (FJC). Compared to animals self-administering saline, animals self-administering MDPV demonstrated (1) robust drug intake that escalated over time, (2) deficits in NOR but not SOR, and (3) neurodegeneration in the perirhinal and entorhinal cortices. These results indicate that repeated binge-like intake of MDPV can induce neurocognitive dysfunction. In addition, utilization of rodent models of extended binge-like intake may provide insight into potential mechanisms and/or approaches to prevent or reverse the detrimental effects of abused substances on cognitive and neurobiological functioning.

Keywords: synthetic cathinone, pyrovalerone, MDPV, self-administration, binge, novel object recognition, spatial object recognition, neurodegeneration, entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex

1. Introduction

Frequently referred to as “bath salts” or other fictitious retail products, synthetic cathinones are β-keto amphetamines designed to mimic the effects of more traditionally abused illicit drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine (Banks et al., 2014, Baumann, 2014, Karila et al., 2015). Synthetic cathinones are derivatives of the naturally occurring alkaloid cathinone found in Catha edulis (Khat), and drugs carry a high risk of inducing severe adverse reactions including agitated delirium, psychosis, seizures, and multiple organ failure. Toxicity resulting from use of synthetic cathinones has resulted in numerous deaths, and between the years 2006 and 2011 were associated with >22,000 emergency department visits in the United States, underscoring the threat these drugs pose to public health (Maxwell, 2014). Although federal agencies have classified various cathinone derivatives as Schedule I controlled substances, numerous other derivatives continue to be developed, with many more likely to emerge in the foreseeable future.

Synthetic cathinones exert their pharmacological effects via mechanisms similar to those exerted by traditional psychostimulants. For example, 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone) and methylone act as monoamine releasing agents similar to amphetamines, while other synthetic cathinones including 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), pentedrone, and α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP) inhibit presynaptic monoamine transporters (e.g., dopamine and norepinephrine transporters, DAT and NET, respectively) in a manner similar to cocaine (Baumann et al., 2013, Simmler et al., 2013, Glennon, 2014, Baumann et al., 2017). In contrast to cocaine, however, MDPV and α-PVP can exert up to 100 times greater potency at inhibiting DAT and NET function, and also have longer durations of action and negligible affinities for presynaptic serotonin transporters (Baumann et al., 2013, Simmler et al., 2013, Simmler and Liechti, 2017).

In order to further understand the abuse liability, mechanisms of action, and toxic effects of synthetic cathinones, investigators have employed rodent models of drug intake, including the intravenous self-administration paradigm. Many synthetic cathinones, including mephedrone, MDPV, α-PVP, function as reinforcers in this paradigm and are readily self-administered via the intravenous route, as reviewed elsewhere (Watterson and Olive, 2014, Aarde and Taffe, 2017, Watterson and Olive, 2017). Yet most, if not all, of these prior studies in rodents were conducted under conditions of limited daily access (e.g, 1–6 hr/day), and it is clear from a myriad of case reports that human synthetic cathinones users often engage in binge-like patterns of intake spanning several consecutive days or even weeks (Winstock et al., 2011, Ross et al., 2012, Forrester, 2013, Gunderson et al., 2013, Miotto et al., 2013, Wright et al., 2013, Hall et al., 2014, Palamar et al., 2015, Barrio et al., 2016). It is therefore of great importance to implement rodent models of long term repeated binge-like self-administration patterns that are frequently observed in human synthetic cathinone users.

Long-term use of traditional psychostimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine can result in impaired cognition, including deficits in working memory, attention, self-control, and behavioral flexibility, the latter of which are major factors in perpetuating drug intake and relapse (Dean et al., 2013, Potvin et al., 2014, London et al., 2015, Bernheim et al., 2016). These cognitive impairments are often paralleled by varying degrees of neuropathology in the underlying neural circuits, which we collectively refer to as “neurocognitive dysfunction”. A small but growing body of literature suggests that synthetic cathinones induce similar neurocognitive dysfunction. For example, mephedrone use in humans is associated with deficits in working memory and verbal recall (Freeman et al., 2012, de Sousa Fernandes Perna et al., 2016, Jones et al., 2016). In rodents, mephedrone or methylone exposure induces deficits in working memory as well as object recognition and discrimination (Motbey et al., 2012, den Hollander et al., 2013, Shortall et al., 2013, Lopez-Arnau et al., 2014, Lopez-Arnau et al., 2015), which can be often accompanied by changes in striatal levels of proteins involved in monoamine transmission such as presynaptic dopamine or serotonin transporter (DAT or SERT, respectively, as reviewed elsewhere (Angoa-Perez et al., 2017). However, few studies to date, if any, have examined neurocognitive dysfunction induced by synthetic cathinones with monoamine reuptake inhibiting properties such as MDPV.

The goal of the present study was to utilize a recently developed rodent model of repeated binge-like psychostimulant self-administration to examine effects of prolonged intake of MDPV on cognitive functioning as well as its ability to produce any evidence of neuropathology. In this paradigm, rodents are allowed four consecutive days (96-hr) of access to intravenous drug self-administration, followed by 3 days of abstinence in the home cage. This process is then repeated four times to allow for a total of 5 weeks of binge-like access interspersed with periods of abstinence (Cornett and Goeders, 2013). Following binge-like self-administration of MDPV, we examined spatial object recognition (SOR) and novel object recognition (NOR) memory function, which have been shown to be compromised following long-term psychostimulant self-administration in rodents (Reichel et al., 2011, Reichel et al., 2012). Finally, since recent in vitro studies suggest that synthetic cathinones including MDPV can induce cytotoxic effects in various cell types (Rosas-Hernandez et al., 2016a, Rosas-Hernandez et al., 2016b, Wojcieszak et al., 2016, Valente et al., 2017), we sought to determine if any observed cognitive deficits were paralleled by evidence of neurodegeneration in their underlying brain circuits.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were purchased from Envigo (formerly Harlan Laboratories, Placentia, CA, USA). Upon arrival, animals were pair-housed in a temperature and humidity controlled vivarium on a reversed light-dark cycle (12:12; lights off at 06:00 h), and were allowed to acclimate for one week prior to commencement of experimental procedures. Food and water were available ad libitum at all times except during object placement and recognition testing. Following implantation of intravenous catheters, rats were singly housed to prevent cagemate chewing on vascular access ports. Rats were weighed once weekly throughout all phases of the study, and testing procedures were conducted during the dark phase of the light-dark cycle. All procedures were conducted according to the National Research Council’s Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Arizona State University. All efforts were made to minimize animal pain and distress and to reduce the total number of animals used.

2.2. Drugs

3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) was obtained from Laboratory Supply USA (San Diego, CA, USA) and verified for >95% purity by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry as previously described (Watterson et al., 2014). MDPV was dissolved in sterile saline for intravenous self-administration (St. Louis, MO). All veterinary pharmaceuticals were obtained from Henry Schein Animal Care (Melville, NY, USA).

2.3. Surgical procedures

Surgical implantation of intravenous catheters was performed according to our previously published methods (Watterson et al., 2014). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and an incision was made on the ventral side of the neck to expose the jugular vein. Polyurethane catheters (Access Technologies, Skokie, IL, USA) were inserted 3.0 cm into the vein, secured with braided silk sutures, and the distal end of the catheter was tunneled subcutaneously to exit the skin through a 3-mm incision hole made between the scapulae. The catheter was then connected to a vascular access port (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) mounted on the dorsum. Following implantation, access ports were flushed with 0.2 ml of antibiotic solution (66.6 mg/ml Timentin in 70 U/ml heparinized saline) and capped with a silastic plug when not in use. Rats received one week of post-operative care with daily infusions of antibiotic solution to maintain catheter patency, and application of a topical antibiotic ointment to protect against infection. In addition, meloxicam (2 mg/kg s.c.) and buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg s.c.) were administered twice daily for the first 3 days of recovery to reduce post-surgical discomfort. Animals were then randomly assigned to undergo self-administration of MDPV or saline. Yoked administration of either saline or MDPV was not utilized as a control since intravenous saline infusions have been shown to produce interoceptive effects and brain activation (Kiyatkin and Lenoir, 2011), and yoked psychostimulant administration has aversive properties and reduces motivation for drug intake (Mutschler and Miczek, 1998, Twining et al., 2009). Both of these factors might have confounded results obtained during drug self-administration and/or subsequent cognitive testing or assessment of neurodegeneration.

2.4. Self-administration apparatus

Intravenous drug self-administration was conducted in computer-interfaced and controlled operant conditioning chambers (Med Associates, Model ENV-007, St. Albans, VT, USA). Each chamber was equipped with a 2.5-cm retractable “active” lever and a non-retractable “inactive” lever located approximately 7 cm above a stainless steel rod floor. Positioned above each response lever was a 2.5-cm diameter white stimulus light to provide a visual cue during drug infusions, and located near the top of the chamber was a Sonalert speaker that provided an auditory stimulus (~65 dB, 2900 Hz) during drug delivery. Each chamber contained a house light that was programmed to the same on/off times and light:dark cycle duration as the colony room. Each chamber was also equipped with a water bottle, and food pellets were placed on the floor of the chamber every morning during each 96-hr session. Located atop each chamber was a liquid swivel connected to a computer-controlled syringe pump (Med Associates) for intravenous drug infusions, which were delivered through polyethylene tubing housed within a stainless steel tether. Operant conditioning chambers were located in melamine sound-attenuating cubicles equipped with a house light and ventilation fan to mask external noise and odors. Ambient temperatures in the sound-attenuating cubicles were monitored via Track-It data loggers (Monarch Instrument, Amherst, NH, USA) and verified to be maintained at 20.5±1°C.

2.5 Self-administration procedures

Following one week recovery from surgery, rats were allowed to spontaneously acquire MDPV self-administration in 96-hr sessions, which was recently developed as a model of bingelike intake of methamphetamine (Cornett and Goeders, 2013). Self-administration sessions were 96 consecutive hours in length, immediately after which animals were returned to the home cage for 3 days. After the first 7 days of this procedure, the process was repeated 4 times, so that each animal was allowed a total of five 96-hr self-administration sessions, each of which separated by 3 days of abstinence in the home cage (Fig. 1A), lasting a total of 5 weeks. MDPV or saline self-administration was conducted on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement, whereby presses on the active lever resulted in delivery of either sterile saline or MDPV at a dose of 0.03 mg/kg per infusion. This dose was based on previous studies by our laboratory and others that have demonstrated reinforcing effects and/or escalation of drug intake during prolonged access at low doses (Aarde et al., 2013, Watterson et al., 2014, Aarde et al., 2015, Schindler et al., 2016, Gannon et al., 2017). Each MDPV or saline infusion was 2 sec in duration, delivered in a volume of 0.06 ml, and accompanied by simultaneous illumination of the white stimulus light located above the active lever, as well as presentation of an auditory cue. A 20-sec timeout period followed each drug or saline infusion, whereby additional active lever presses were recorded but had no programmed consequences. Each press on the inactive lever produced no programmed consequences at any time during the experiment. Prior to and following each 96-hr session, catheters were flushed with 0.1 ml of 66.6 mg/ml Timentin in 70 U/ml heparinized saline to maintain catheter patency and minimize infection. Successful acquisition of MDPV self-administration was defined as rats obtaining at least 10 infusions per session by the end of the third 96-hr session. Overall animal health was assessed twice daily, and body weights were recorded immediately before and after each 96 hr access period for calculation of drug intake levels in mg/kg.

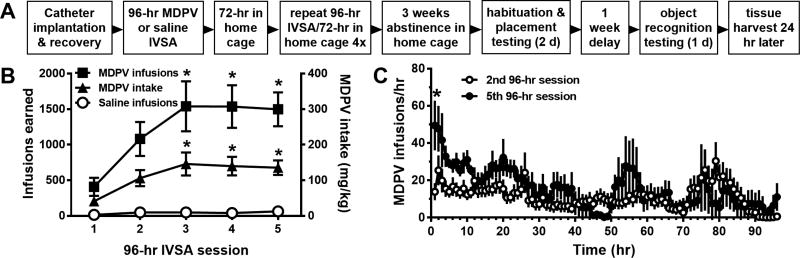

Fig 1.

A. Diagram of the experimental procedures used in the present study. B. Total number of MDPV or saline infusions obtained (left y-axis) and overall MDPV intake (right y-axis) across the five 96-hr self-administration sessions. *p<0.05 vs. first 96-hr session. C. Temporal pattern of MDPV self-administration in 1-hr time bins during the 2nd and 5th 96-hr self-administration periods. *p<0.05 vs. the same time bin in 2nd 96-hr session. Group sizes are n=13 for rats self-administering MDPV and n=8 for rats self-administering saline. Abbreviations: IVSA, intravenous self-administration, MDPV, 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone.

2.6. Spatial and novel object recognition testing

Following the last 96-hr self-administration session, animals were returned to their home cage and left undisturbed for 3 weeks (Fig. 1A). The duration of this period of abstinence was chosen to maximize clearance of MDPV as well as to minimize the influence of any potential bioactive metabolites. Previous studies have shown that the plasma elimination half-life of MDPV is ~90 min in rats, and that general motor activity is not influenced by MDPV metabolites (Anizan et al., 2016, Baumann et al., 2017). However, these prior studies were conducted using acute dosing procedures, and it is currently unknown whether significant MDPV and/or metabolite accumulation occurs in plasma or other tissue compartments following long-term self-administration over numerous weeks. A 3-week abstinence period was utilized to minimize this potential confound, as well as minimize the influence of withdrawal-induced dysphoria or anxiety-like behaviors on object exploration (Ennaceur, 2010, Antunes and Biala, 2012). For spatial object recognition (SOR) testing, an opaque acrylic open field arena (60 × 60 × 20 cm) with floor light intensity of ~250 lux was used, and extra-maze cues (posters with distinct geometric patterns) were mounted on the walls outside of the arena. For novel object recognition (NOR) testing, the same arena was used, but the lighting intensity level at the floor was reduced to ~80 lux and extra-maze cues were removed. For both procedures, animals were transported to the testing room at approximately 0900 h and allowed to habituate for 1 hr prior to commencement of testing (Bevins and Besheer, 2006).

SOR and NOR testing were conducted according to our previously published methods (Reichel et al., 2011, Nishimura et al., 2017). For SOR testing, animals were placed individually in the empty arena and allowed to habituate for 10 min, after which the animal was returned to the home cage. Object familiarization commenced 24 hr later, where two identical objects (empty green plastic soap dispensers, ~20 × 20 × 10 cm) were placed equidistant from the arena corners, and the animal placed into the arena and allowed free exploration for 3 min, followed by being returned to the home cage for 90 min. The 90-min delay period was selected to be the same as that used for NOR testing (see below), which was chosen based on our previous findings of NOR deficits induced by extended methamphetamine self-administration (Reichel et al., 2011). Following the delay period, one of the objects was moved to a different quadrant of the arena, and the animal was then returned to the arena and allowed free exploration for 3 min, followed by return to the home cage. The selection of the object moved was counterbalanced across animals within each experimental group.

NOR testing commenced two days after the end of SOR testing. This 2-day period was selected based on prior studies by our laboratory and others demonstrating significant loss of prior object memory after 24 hr (Ennaceur and Delacour, 1988, Reichel et al., 2011), thus minimizing any potential influence of prior SOR testing on results obtained in the NOR task. During familiarization, rats were allowed free exploration of two new identical objects (a combination of two of the following: an empty red 0.95 L plastic sharps collector, a nonfunctional yellow plastic flashlight stood on one end, or a green plastic tumbler cup placed upside down, each ~20 × 20 × 10 cm) for 3 min. Animals were then returned to the home cage, and recognition testing commenced 90 min later, where one of the objects was replaced with the previously unused object described above, and the animal was allowed free exploration of both objects for 3 min, followed by return to the home cage. The combinations of objects used was counterbalanced across animals within each experimental group.

For all SOR and NOR testing, animals were placed into the arena facing away from the objects to minimize object proximity bias. After each trial, the testing arena and objects were wiped down with 70% ethanol and allowed to dry. Object exploration was defined as orientation toward the object with the snout <3 cm from the object. Data from animals spending <10 sec total object exploration time were excluded from analyses. All sessions were video recorded and analyzed later by a blinded investigator. SOR placement index values were calculated as time spent exploring the moved object divided by the time spent exploring both objects. SOR discrimination index values were calculated as the difference in time spent exploring the moved vs. unmoved object divided by the time spent exploring both objects. NOR discrimination index values were calculated as the difference in time spent exploring the novel vs. familiar objects divided by the time spent exploring both objects (Antunes and Biala, 2012). Object exploration during the familiarization trials was also assessed to confirm an absence of side and/or object bias or avoidance.

2.7. Assessment of neurodegeneration

A 2-day period between NOR testing and euthanasia was allowed to allow for preparation of reagents and to minimize potential influences of animal transport stress on neurodegeneration. Animals were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg i.p.) and perfused by the transcardial route with saline followed by 4% w/v paraformaldehyde. As a positive control for assessment of neurodegeneration, a separate group of experimentally naïve animals were administered the neurotoxin kainic acid (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) at a dose of 8 mg/kg i.p. once daily for 3 days (Wang et al., 2005). Kainic acid was dissolved in physiological saline, and neurotoxin-treated animals were euthanized by transcardial perfusion as described above 48 hr after the last injection. Brains were then post-fixed for at least 48 hr in the same fixative at 4°C, cryoprotected in 30% w/v sucrose for at least 48 hr, and coronal sections through the mPFC, Ect, PRh and Ent were obtained at 40 µm thickness on a Leica CM1900 cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) and mounted onto gelatin-coated microscope slides. Slides were heated overnight at 50°C prior to Fluorojade C staining (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), which was performed according to the manufacturer directions and previously published methods (Schmued et al., 2005). Briefly, slides were immersed sequentially in the following solutions: 80% ethanol/1% NaOH for 5 min, 70% ethanol for 2 min, dH2O for 2 min, 0.06% w/v KMnO4 for 15 min, dH2O for 2 min, 0.0001% w/v FluoroJade C + 0.1% acetic acid for 10 min, and dH2O 3 × 1 min. Slides were then dried on a slide warmer at 50°C for 30 min, immersed in xylene for 2 min, coverslipped using DePeX mounting media (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA), and stored in darkness until microscopic analysis.

For quantification of FJC-positive neurons, sections containing the regions of interest were viewed at an excitation wavelength of 473 nm at ×10 magnification using a Hamamatsu Digital Camera (Hamamatsu City, Japan) attached to an Olympus BX53 microscope (Olympus Life Sciences, Center Valley, PA, USA). Sequential images were stitched into a single 8-bit TIFF image using Olympus cellSens software. FJC-positive cell counts in each region were quantified by a blinded investigator utilizing the Count tool in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA), and the area of each region of interest (in mm2) was calculated using the Polygonal Lasso tool in conjunction with a stereotaxic atlas of the rat brain (Paxinos and Watson, 2014). A calculated pixel size of 0.6498 pixels per micron was utilized for determination of brain region area. A neuron-like morphology (see Fig. 1C) was necessary in order for cells to be considered FJC-positive neurons. Due to the known non-specific staining by FJC of the meninges and ventricular ependymal cells (Schmued et al., 2005, Schmued, 2016), staining within 100 µm of tissue edges was excluded from analyses. A total of 4–8 sample areas of each region were counted for each animal, and resulting values were averaged together to provide a mean number of FJC-positive cells per animal for statistical analyses.

2.8 Statistical analyses

All data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and all statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v.7.03 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The number of MDPV vs. saline infusions obtained across the five 96-hr sessions was analyzed by two-way ANOVA. The amount of MDPV self-administered across the five 96-hr sessions was analyzed by a separate one-way ANOVA. To assess potential changes in MDPV intake patterns between earlier and later 96-hr sessions, the number of MDPV infusions in the 2nd vs. 5th 96-hr sessions were calculated in 1-hr bins, and analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Data from SOR and NOR testing (placement and/or discrimination indices) were analyzed by Student’s t-test. The amount of time spent exploring both objects during the SOR and NOR tasks were compared across group using a one-way ANOVA. Due to the large difference in means of the number of FJC-positive cells per mm2 in each brain region for kainic acid treated positive controls vs. rats self-administering MDPV or saline, separate two-way ANOVAs were conducted for comparing kainic acid vs. saline and MDPV vs. saline animals. All analyses were followed by appropriate post hoc test, including Tukey or Bonferroni corrections involving repeated measures where appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Final group sizes

A timeline of all procedures is shown in Fig. 1A. A total of n=24 animals underwent catheter implantation. Of these, n=2 were removed from the study due to loss of catheter patency, and n=2 were found dead in the operant self-administration apparatus during the first 96-hr session due to unknown causes, yielding final group sizes of n=13 rats self-administering MDPV and n=8 rats self-administering saline. Data from n=2 animals with a history of saline self-administration and n=1 animal with a history of MDPV self-administration were excluded from analysis of object placement or recognition testing due to failure to meet the minimum criteria for object exploration (10 sec) during the trial. Finally, FJC staining could not be quantified in brain sections from n=6 rats from the MDPV self-administration group and n=2 rats from the saline self-administration group due to excessive background fluorescence. It was empirically determined that high background levels were related to insufficient drying of tissue sections prior to immersion in xylene, which was subsequently corrected for all remaining tissue. Thus, final group sizes for FJC quantification were n=7 and n=6 for animals self-administering MDPV or saline, respectively.

3.2. Patterns of MDPV self-administration in 96-hr sessions

By the end of the second 96-hr self-administration session, all animals self-administering MDPV displayed at least a 3:1 ratio of active to inactive lever presses (data not shown). These observations confirm the reinforcing effects of MDPV infusions produced by presses on the active lever. Levels of saline self-administration were consistently low, and animals in this group did not display any preference for the active or inactive lever (data not shown). Analysis of the overall number of infusions earned across each of the five 96-hr sessions revealed a significant effect of reinforcer (MDPV or saline, F1,84=36.74, p<0.0001), with greater number of MDPV infusions earned as compared to saline (Fig. 1B). However, overall effects of session number or a session × reinforcer interaction were not statistically significant (all p-values > 0.05). Post hoc analyses indicated that the number of MDPV infusions was greater during the 3rd, 4th and 5th sessions as compared to the first session (all p-values <0.01), and the same was true for the amount of MDPV intake (all p-values<0.01). No change in the number of saline infusions obtained across the five 96-hr sessions was observed (p>0.05).

Patterns of acquisition of MDPV self-administration in the first 96-hr session were highly variable, as intake in individual animals ranged from only a few infusions obtained to several hundred (data not shown). More stable intake patterns were observed in the latter four 96-hr sessions. To obtain a temporal profile of self-administration patterns and potential change over time, the number of infusions obtained during the 2nd and 5th 96-hr sessions were calculated in 1-hr time bins (Fig. 1C). Analyses of these temporal profiles revealed a significant effect of session number (F1,1920=25.67, p<0.001) and time bin (F5,1920=2.81, p<0.0001). However, a significant interaction effect was not observed (F95,1920=1.20, p=0.09). Post-hoc comparisons revealed significantly greater MDPV infusions only during the 1st 1-hr time bin (p<0.05, Fig. 1C), and no other comparisons were significantly significant.

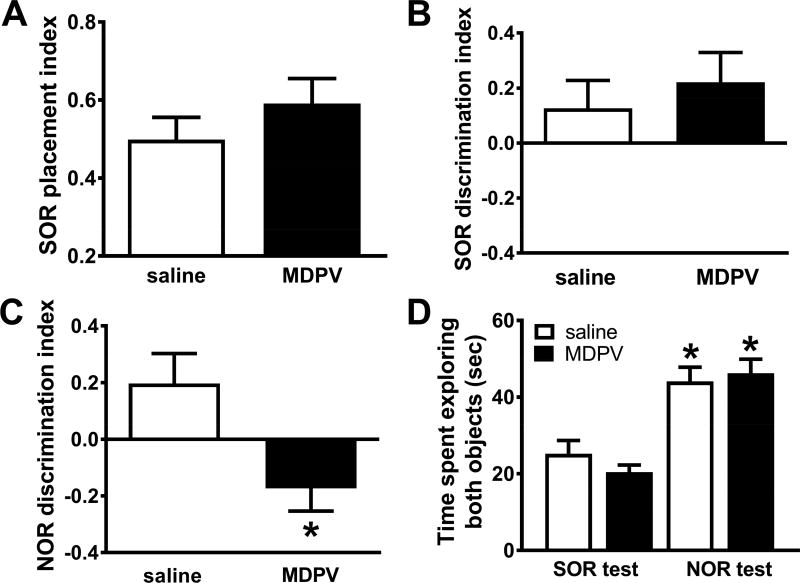

3.2. Effects of MDPV self-administration on object placement and recognition memory function

Rats with a history of MPDV self-administration did not differ in SOR placement (t14=0.99, p>0.05; Fig. 2A) and SOR discrimination index (t16=0.54, p>0.05; Fig. 2B) values as compared to rats with a history of saline self-administration. However, rats with a history of MPDV self-administration showed significantly lower NOR discrimination index scores (t18=2.78, p<0.05; Fig. 2C) as compared to rats with a history of saline self-administration, indicating that MDPV self-administration impaired NOR memory function. Analysis of the total time spent exploring the objects revealed a significant overall main effect (F3,34=17.26, p<0.0001), and post hoc comparisons revealed no differences between rats self-administering saline and those self-administering MDPV during each test session (p’s >0.05). However, both self-administration groups displayed increased time exploring both objects during object recognition testing (conducted last) as compared to during object placement testing (p’s <0.01, Fig. 2D). No group differences in time spent exploring objects during the familiarization phase were observed (p>0.05).

Fig. 2.

Performance in the SOR and NOR tasks in rats with a history of MDPV (n=12) or saline (n=6) self-administration. No differences in SOR placement index (A) or SOR discrimination index (B) values were observed. C. NOR discrimination index values were significantly reduced in rats with a history of MDPV self-administration (*p<0.05 vs. saline self-administering rats). D. No group differences were observed in total time spent exploring both objects during object placement or recognition testing, However, both groups of animals displayed significantly more time exploring both objects during the NOR testing (*p<0.01 vs. the respective group during SOR testing.

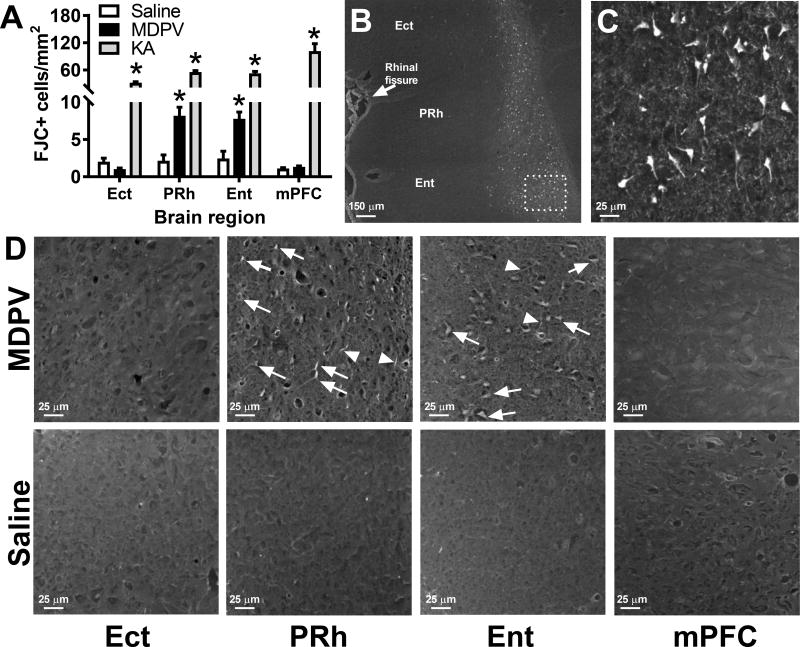

3.3. Effects of MDPV self-administration on neurodegeneration as assessed by FJC staining

Quantitative analysis of FJC staining revealed significant effects of brain region (F3,44=27.35, p<0.0001), self-administration group (MDPV or saline, F1,44=18.61, p<0.0001), and an interaction (F3,44=12.29, p<0.0001). Compared with rats with a history of saline self-administration, MDPV self-administering rats showed increased levels of FJC staining in the PRh and Ent cortices, but no differences were observed across groups for the mPFC and Ect (Fig. 3A and 3D). In the PRh and Ent, we observed no consistent pattern of MDPV-induced FJC across superficial vs. deeper layers of the cerebral cortex. As expected, rats treated with KA as a positive control displayed robust FJC staining that were significantly elevated in all brain regions as compared to rats with a history of saline self-administration (treatment group effect F1,32=284.9, brain region effect F3,32=17.53, interaction F3,32=18.69, all p-values < 0.0001; Fig. 3A–3C). In KA treated animals, FJC staining was largely confined to deeper layers of the cerebral cortex (Fig. 3B), consistent with the expression patterns of high affinity kainate receptors (Wisden and Seeburg, 1993). Finally, consistent with detailed characterizations of FJC staining patterns (Schmued et al., 2005, Schmued, 2016), non-specific staining was observed in the meninges and ventricular ependymal cells, and thus staining in these regions or within 100 µm of tissue edges was not quantified or analyzed. Several other brain regions were also examined for FJC staining including the hippocampus, striatum, and ventral midbrain, but due to the general absence of staining in both MDPV and saline self-administering animals in these regions (data not shown), quantification of FJC staining in these regions was not performed.

Fig. 3.

A. Quantification of neurodegeneration in rats with a history of MDPV (n=7) or saline (n=6) self-administration, and rats treated with kainic acid as a positive control (n=4). *p<0.05 vs. saline self-administering animals within the same brain region. B. Representative images of FJC staining in the ectorhinal (Ect), perirhinal (PRh), and entorhinal (Ent) cortices of an animal treated with kainic acid. Robust FJC staining was primarily observed in deeper layers of the cerebral cortex, and similar observations were made in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC, not shown). Photograph at top right shows higher magnification of boxed area in B. C. Representative photographs of FJC staining in the Ect, PRh, Ent, and mPFC in rats with a history of MDPV or saline self-administration. Arrows denote FJC-positive neurons, and arrowheads denote FJC-positive fibrous processes.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we utilized a recently developed rodent model of prolonged binge-like psychostimulant self-administration (Cornett and Goeders, 2013) to demonstrate that long-term intake of the synthetic cathinone MDPV produces escalation of drug intake over time, as well as deficits in NOR memory. In addition, we demonstrate that these cognitive deficits are paralleled by neurodegeneration in the perirhinal and entorhinal cortices, two regions known to be involved in recognition memory function. Taken together, these findings suggest that extended MDPV self-administration produces neurocognitive dysfunction and neurotoxicity.

Previous studies have demonstrated that MDPV serves as a potent reinforcer and is readily self-administered by laboratory rodents (Aarde et al., 2013, Watterson et al., 2014, Aarde et al., 2015, Schindler et al., 2016, Gannon et al., 2017). However, these prior studies utilized daily self-administration sessions that varied from 1 to 6 hr in length. While such procedures are useful in modeling daily use patterns, they do not necessarily recapitulate the multi-day binge episodes in which synthetic cathinone users often engage (Winstock et al., 2011, Ross et al., 2012, Forrester, 2013, Gunderson et al., 2013, Miotto et al., 2013, Wright et al., 2013, Hall et al., 2014, Palamar et al., 2015, Barrio et al., 2016). Further studies are needed to systemically compare the degree of neurocognitive dysfunction induced by either daily yet limited drug self-administration, and that induced by repeated multi-day binge-like intake.

MDPV is a potent cocaine-like psychostimulant that produces long-lasting inhibition of DAT and NET, with negligible affinity for SERT (Baumann et al., 2013, Simmler et al., 2013, Baumann et al., 2017, Simmler and Liechti, 2017). The present study demonstrates that in 96-hr sessions, rodents will self-administer considerable amounts (up to 300 mg/kg) of this drug (see Fig. 1B). When analyzed in 1-hr time bins, we did not observe significant differences in intake patterns between the 2nd and 5th sessions, except during the first hour of the session where intake was elevated in the latter session. Other investigators have shown that rats engage in binge-like acquisition of MDPV self-administration, with high intake levels occurring the first portion of each session, even without an extensive history of prior intake (Aarde et al., 2015). In the present study, we found acquisition of MDPV self-administration during the first 96-hr session was highly variable between animals, likely a result of individual differences in reinforcer sensitivity (Aarde et al., 2015, Gannon et al., 2017). The observed increase in MDPV intake during the first hour of the 5th 96-hr session as compared to the 2nd session may be more reflective of a “loading phase” escalation of intake, as has been described for patterns of cocaine or methamphetamine when daily sessions are extended from 1 to 6 hr in duration (Ahmed and Koob, 1998, Ahmed and Koob, 1999, Kitamura et al., 2006, Wee et al., 2007). Additional studies employing different schedules of reinforcement, higher doses of MDPV, other synthetic cathinones with either monoamine reuptake inhibiting properties (e.g., α-PVP) or monoamine releasing properties (e.g., mephedrone), are needed to empirically assess the specific behavioral or pharmacological components that contribute to synthetic cathinone-induced neurocognitive dysfunction.

Similar to studies that have observed deleterious effects of prolonged daily access to methamphetamine on NOR memory function (Reichel et al., 2011, Reichel et al., 2012), we observed NOR deficits following prolonged binge-like intake of MDPV. While we are unaware of other studies examining neurocognitive dysfunction following exposure to MDPV, our findings are in general agreement with others that have reported deficits in working memory and object recognition and discrimination following subchronic administration of high doses of other synthetic cathinones such as mephedrone or methylone (Motbey et al., 2012, den Hollander et al., 2013, Shortall et al., 2013, Lopez-Arnau et al., 2014, Lopez-Arnau et al., 2015), as well as deficits in working memory and verbal recall that have been reported in human synthetic cathinone users (Freeman et al., 2012, de Sousa Fernandes Perna et al., 2016, Jones et al., 2016). In addition, it was recently reported that acute MDPV administration causes widespread reductions in functional connectivity between cortical and subcortical structures (Colon-Perez et al., 2016). Thus, if such functional disconnection occurs during voluntary MDPV self-administration, these effects may have contributed to the impairments in NOR memory observed in the present study.

However, we found that SOR memory in MDPV self-administering animals was unaltered, suggesting that at least under the present conditions, spatial object memory is not altered by binge-like MDPV intake. Additional studies employing more sophisticated spatial navigation and working memory tasks following prolonged MDPV self-administration are needed to verify the presence or absence of MDPV-induced spatial memory deficits. In addition, these negative findings should be interpreted with caution, as we observed that total object exploration was lower during SOR testing as compared to that observed during subsequent NOR testing, regardless of history of MDPV or saline self-administration. The most likely explanation for this is that animals were tested in the same arena in both SOR and NOR tasks, although the environment differed in terms of objects used, lighting intensity, and presence of extramaze cues. Prior studies have demonstrated that familiarization with the testing environment results in increased object exploration time during subsequent trials (Besheer and Bevins, 2000, Bevins and Besheer, 2006), likely a result of habituation to the testing arena itself. In addition, the order of SOR and NOR testing was not counterbalanced in the present study, and thus effects of MDPV on SOR memory function may have been observed if animals had been provided additional arena habituation time. Therefore, future studies are needed to assess potential disruptions in SOR memory under conditions of higher motivation to explore the objects (i.e., following increased environmental familiarization), as well as the context-specificity of these effects. Nonetheless, the fact that object exploration times were elevated in both MDPV and saline self-administering animals suggests a lack of influence of drug history on these measures.

The PRh cortex plays a key role in NOR memory by integrating sensory information from nearby association cortices to discriminate the recency and novelty of external stimuli (Winters et al., 2008, Ennaceur, 2010, Cohen and Stackman, 2015, Warburton and Brown, 2015). This region has reciprocal connections with the mPFC which incorporate aspects of working memory (e.g., temporal order) into object recognition (Barker et al., 2007, Morici et al., 2015). A primary output target of the PRh is the entorhinal cortex (Ent), which in turn sends efferent projections to the hippocampus which mediates spatial (e.g., placement) memory as well as contextual or temporal components (Winters et al., 2008, Ennaceur, 2010, Cohen and Stackman, 2015, Warburton and Brown, 2015). Dorsal to the PRh is the ectorhinal cortex (Ect), which does not appear to be involved in recognition memory (Winters et al., 2008, Ennaceur, 2010, Cohen and Stackman, 2015, Warburton and Brown, 2015). In the present study, we observed evidence of neurodegeneration in the PRh and Ent in rats with a history of binge-like MDPV intake, utilizing FJC as a fluorescent marker of degenerating neurons (Schmued et al., 2005, Schmued, 2016). However, there were no observable increases in FJC staining in the Ect or mPFC in rats with a history of MDPV self-administration, and while an exhaustive analysis of FJC staining throughout the entire brain was not conducted, we did not observe significant FJC staining in other regions including the hippocampus, striatum, or ventral midbrain (data not shown). Additional studies utilizing other histochemical markers of neurodegeneration are needed to confirm the extent of the neurotoxic effects of MDPV following long-term binge-like intake.

The reasons for the apparent selective vulnerability of neurons in the PRh and Ent cortices to MDPV-induced neurodegeneration are currently unknown. Interestingly, these same regions, particularly the Ent cortex, is particularly vulnerable to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease, as it is among the first regions to show evidence of neuronal cell death in early stages of the disease (Stranahan and Mattson, 2010, Saxena and Caroni, 2011). While this neurodegenerative disease has a vastly different and more complex etiology and neuropathological profile as compared to psychostimulant abuse, there may be some common mechanisms underlying the vulnerable predisposition of neurons in the Ent and PRh cortices. For example, neurons in the PRh and Ent cortices appear to be vulnerable to the effects of neuroinflammation (Cribbs et al., 2012), a phenomenon well-documented to occur in psychostimulant abuse (Clark et al., 2013, Loftis and Janowsky, 2014). Alternatively, these regions may be particularly susceptible to drug-induced glutamatergic excitotoxicity (Eid et al., 1995). A recent study by Gregg and colleagues (Gregg et al., 2016) found that MPDV down-regulates the expression of glutamate transporter subtype I (GLT-1), thereby increasing extracellular levels of glutamate which could potentially lead to excitotoxicity. However, this study found GLT-1 expression to be altered in the nucleus accumbens but not the mPFC, and did not examine parahippocampal regions such as the PRh and Ent. Other studies have found that psychostimulants such as methamphetamine decrease total levels or cell surface expression of the metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5 and the ionotropic glutamate receptor subunit GluN2B in the PRh, which may have inhibitory effects on adaptive synaptic oplasticity that occurs as a result of a hyperglutamatergic transmission in this region (Reichel et al., 2011, Scofield et al., 2015). Future studies are needed to examine the precise molecular and neurophysiological changes that selectively occur in the Ent and PRh cortices following prolonged MDPV intake that may mediate vulnerability of neurons in these regions to the neurotoxic effects of this synthetic cathinone.

Recent in vitro studies conducted in various cell lines, including hepatocytes and SH-SY5Y dopaminergic neurons, have also revealed cytotoxic effects of MDPV (Rosas-Hernandez et al., 2016a, Rosas-Hernandez et al., 2016b, Wojcieszak et al., 2016, Angoa-Perez et al., 2017, Luethi et al., 2017, Valente et al., 2017). Such toxic effects were accompanied by increased production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, reduced intracellular glutathione levels and depletion of cellular ATP stores, and mitochondrial dysfunction, as well as induction of apoptosis and necrosis. It is therefore possible that long-term MDPV intake and the accompanying prolonged elevations in extracellular dopamine may result in increased formation of oxidative dopamine metabolites (Cunha-Oliveira et al., 2008, Angoa-Perez et al., 2017), resulting in oxidative stress and eventual neurodegeneration in the PRh and Ent. However, as noted above, we did not observe evidence of neurodegeneration in regions receiving dense dopaminergic innervation including the dorsal and ventral striatum. It is possible that other mechanisms may contribute to the toxicity of MDPV, including induction of pro-apoptotic signaling pathways, gliosis, and compromised blood-brain barrier function (Cui et al., 2014, Pereira et al., 2015, Soleimani et al., 2016). Clearly, additional studies are warranted to investigate this possibility.

Several limitations of the current study are worth noting. First, while we verified a consistent ambient temperature of 20.5±1°C in the operant testing apparatus during prolonged MDPV access, it is possible that hyperthermia produced by MDPV itself (Borek and Holstege, 2012, Kiyatkin et al., 2015, Valente et al., 2016, Gannon et al., 2017) may have contributed to the neurotoxic effects of this drug. In addition, the potent and long-lasting psychostimulant properties of MDPV, especially when self-administered in across multiple days and weeks, may have produced substantial sleep deprivation that contributed to the neurotoxic effects of this drug. However, evidence for neurotoxicity following prolonged sleep deprivation in rats is mixed, with some studies finding no effects of forced sleep deprivation on neuronal cell death or necrosis (Cirelli et al., 1999, Hipolide et al., 2002), while others have found increases in apoptosis and blood-barrier permeability following sleep deprivation, particularly following loss of rapid eye movement sleep (Biswas et al., 2006, Gomez-Gonzalez et al., 2013, Everson et al., 2014). It is therefore possible that prolonged wakefulness induced by binge-like MDPV intake in combination with the pharmacological effects of the drug may have contributed to the neurocognitive dysfunction observed in the current study. Finally, it should be noted that we utilized Timentin (ticarcillin and clavulanate) as an antibiotic to minimize infection following intravenous catheter implantation and throughout the self-administration phase of the study. As a beta-lactam based antibiotic, Timentin (particularly clavulanate) has the potential to upregulate the expression of GLT-1 (Kim et al., 2016), thus counteracting down-regulation of this transporter induced by MDPV intake (Gregg et al., 2016), ultimately leading to changes in glutamate homeostasis and the potential to alter the reinforcing and/or neurotoxic effects of MDPV. Unfortunately, we have found that antibiotics lacking beta-lactamase activity are ineffective in reducing post-operative infections in our laboratory, presumably due to microbial resistance of the bacterial species present. Further studies are needed to control for the potential influence of the aforementioned factors in the MDPV-induced neurocognitive dysfunction observed in the present study.

5. Conclusions

Self-administration paradigms incorporating prolonged, multi-day access to intravenous drug solutions, interspersed with periods of abstinence, are of great utility in examining potential effects of synthetic cathinones and other abused psychostimulants on neurocognitive function. We observed that prolonged MDPV intake produces deficits in specific cognitive functions, particularly NOR memory, while appearing to leave SOR memory intact. MDPV-induced cognitive deficits were paralleled by evidence of neurotoxicity in regions of the NOR memory circuitry, namely the PRh and Ent, while other regions including the Ect, mPFC, hippocampus and striatum were unaffected. Overall, these findings suggest that long-term MDPV use poses risks for inducing impaired cognitive function and neurodegeneration in specific brain regions.

Highlights.

Binge-like MDPV intake in 96-hr sessions produces novel object recognition deficits

Binge-like MDPV intake induces neurotoxicity in the perirhinal/entorhinal cortex

Prolonged binge-like intake paradigms can model drug-induced neurocognitive dysfunction

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Candace Lewis for assistance with intravenous catheter implantation surgeries, Theresa Lobato for assistance with behavioral testing, Larry Schmued for assistance in optimizing FJC staining, Cheryl Conrad for advice on the design and analysis of object placement and recognition testing, and Jason Newbern for assistance with microscope image acquisition. This research was funded by Public Health Service grants DA025606 and DA043172 (MFO) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aarde SM, Huang PK, Creehan KM, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. The novel recreational drug 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) is a potent psychomotor stimulant: self-administration and locomotor activity in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2013;71:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarde SM, Huang PK, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. Binge-like acquisition of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) self-administration and wheel activity in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:1867–1877. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3819-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarde SM, Taffe MA. Predicting the abuse liability of entactogen-class, new and emerging psychoactive substances via preclinical models of drug self-administration. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;32:145–164. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science. 1998;282:298–300. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Long-lasting increase in the set point for cocaine self-administration after escalation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:303–312. doi: 10.1007/s002130051121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angoa-Perez M, Anneken JH, Kuhn DM. Neurotoxicology of synthetic cathinone analogs. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;32:209–230. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anizan S, Concheiro M, Lehner KR, Bukhari MO, Suzuki M, Rice KC, Baumann MH, Huestis MA. Linear pharmacokinetics of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and its metabolites in the rat: relationship to pharmacodynamic effects. Addict Biol. 2016;21:339–347. doi: 10.1111/adb.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes M, Biala G. The novel object recognition memory: neurobiology, test procedure, and its modifications. Cogn Process. 2012;13:93–110. doi: 10.1007/s10339-011-0430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Worst TJ, Rusyniak DE, Sprague JE. Synthetic cathinones ("bath salts") The Journal of emergency medicine. 2014;46:632–642. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.11.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GR, Bird F, Alexander V, Warburton EC. Recognition memory for objects, place, and temporal order: a disconnection analysis of the role of the medial prefrontal cortex and perirhinal cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2948–2957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5289-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio P, Gaskell M, Goti J, Vilardell S, Fabregas JM. Persistent psychotic symptoms after long-term heavy use of mephedrone: a two-case series. Adicciones. 2016;28:154–157. doi: 10.20882/adicciones.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH. Awash in a sea of ‘bath salts’: implications for biomedical research and public health. Addiction. 2014;109:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/add.12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Bukhari MO, Lehner KR, Anizan S, Rice KC, Concheiro M, Huestis MA. Neuropharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), its metabolites, and related analogs. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;32:93–117. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, Rothman RB, Goldberg SR, Lupica CR, Sitte HH, Brandt SD, Tella SR, Cozzi NV, Schindler CW. Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive ‘bath salts’ products. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:552–562. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim A, See RE, Reichel CM. Chronic methamphetamine self-administration disrupts cortical control of cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;69:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besheer J, Bevins RA. The role of environmental familiarization in novel-object preference. Behav Processes. 2000;50:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(00)00090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins RA, Besheer J. Object recognition in rats and mice: a one-trial non-matching-to-sample learning task to study ‘recognition memory’. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1306–1311. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Mishra P, Mallick BN. Increased apoptosis in rat brain after rapid eye movement sleep loss. Neuroscience. 2006;142:315–331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borek HA, Holstege CP. Hyperthermia and multiorgan failure after abuse of "bath salts" containing 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:103–105. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli C, Shaw PJ, Rechtschaffen A, Tononi G. No evidence of brain cell degeneration after long-term sleep deprivation in rats. Brain Res. 1999;840:184–193. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01768-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KH, Wiley CA, Bradberry CW. Psychostimulant abuse and neuroinflammation: emerging evidence of their interconnection. Neurotox Res. 2013;23:174–188. doi: 10.1007/s12640-012-9334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SJ, Stackman RW., Jr Assessing rodent hippocampal involvement in the novel object recognition task. A review. Behav Brain Res. 2015;285:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Perez LM, Tran K, Thompson K, Pace MC, Blum K, Goldberger BA, Gold MS, Bruijnzeel AW, Setlow B, Febo M. The psychoactive designer drug and bathsalt constituent MDPV causes widespread disruption of brain functional connectivity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:2352–2365. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornett EM, Goeders NE. 96-hour methamphetamine self-administration in male and female rats: A novel model of human methamphetamine addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;111:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs DH, Berchtold NC, Perreau V, Coleman PD, Rogers J, Tenner AJ, Cotman CW. Extensive innate immune gene activation accompanies brain aging, increasing vulnerability to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration: a microarray study. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:179. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C, Shurtleff D, Harris RA. Neuroimmune mechanisms of alcohol and drug addiction. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2014;118:1–12. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801284-0.00001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha-Oliveira T, Rego AC, Oliveira CR. Cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the neurotoxicity of opioid and psychostimulant drugs. Brain Res Rev. 2008;58:192–208. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Fernandes Perna EB, Papaseit E, Perez-Mana C, Mateus J, Theunissen EL, Kuypers K, de la Torre R, Farre M, Ramaekers JG. Neurocognitive performance following acute mephedrone administration, with and without alcohol. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1305–1312. doi: 10.1177/0269881116662635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean AC, Groman SM, Morales AM, London ED. An evaluation of the evidence that methamphetamine abuse causes cognitive decline in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:259–274. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hollander B, Rozov S, Linden AM, Uusi-Oukari M, Ojanpera I, Korpi ER. Long-term cognitive and neurochemical effects of "bath salt" designer drugs methylone and mephedrone. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;103:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid T, Du F, Schwarcz R. Differential neuronal vulnerability to amino-oxyacetate and quinolinate in the rat parahippocampal region. Neuroscience. 1995;68:645–656. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00183-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A. One-trial object recognition in rats and mice: methodological and theoretical issues. Behav Brain Res. 2010;215:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, Delacour J. A new one-trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: Behavioral data. Behav Brain Res. 1988;31:47–59. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(88)90157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson CA, Henchen CJ, Szabo A, Hogg N. Cell injury and repair resulting from sleep loss and sleep recovery in laboratory rats. Sleep. 2014;37:1929–1940. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester MB. Adolescent synthetic cathinone exposures reported to Texas poison centers. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:151–155. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182808ae2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman TP, Morgan CJ, Vaughn-Jones J, Hussain N, Karimi K, Curran HV. Cognitive and subjective effects of mephedrone and factors influencing use of a ‘new legal high’. Addiction. 2012;107:792–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Galindo KI, Rice KC, Collins GT. Individual differences in the relative reinforcing effects of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone under fixed and progressive ratio schedules of reinforcement in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;361:181–189. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.239376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennon RA. Bath salts, mephedrone, and methylenedioxypyrovalerone as emerging illicit drugs that will need targeted therapeutic intervention. Adv Pharmacol. 2014;69:581–620. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00015-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gonzalez B, Hurtado-Alvarado G, Esqueda-Leon E, Santana-Miranda R, Rojas-Zamorano JA, Velazquez-Moctezuma J. REM sleep loss and recovery regulates blood-brain barrier function. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2013;10:197–207. doi: 10.2174/15672026113109990002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg RA, Hicks C, Nayak SU, Tallarida CS, Nucero P, Smith GR, Reitz AB, Rawls SM. Synthetic cathinone MDPV downregulates glutamate transporter subtype I (GLT-1) and produces rewarding and locomotor-activating effects that are reduced by a GLT-1 activator. Neuropharmacology. 2016;108:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EW, Kirkpatrick MG, Willing LM, Holstege CP. Substituted cathinone products: a new trend in "bath salts" and other designer stimulant drug use. J Addict Med. 2013;7:153–162. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829084b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C, Heyd C, Butler C, Yarema M. "Bath salts" intoxication: a new recreational drug that presents with a familiar toxidrome. CJEM. 2014;16:171–176. doi: 10.2310/8000.2013.131042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipolide DC, D’Almeida V, Raymond R, Tufik S, Nobrega JN. Sleep deprivation does not affect indices of necrosis or apoptosis in rat brain. Int J Neurosci. 2002;112:155–166. doi: 10.1080/00207450212022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Reed P, Parrott A. Mephedrone and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine: comparative psychobiological effects as reported by recreational polydrug users. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1313–1320. doi: 10.1177/0269881116653106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila L, Megarbane B, Cottencin O, Lejoyeux M. Synthetic cathinones: a new public health problem. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:12–20. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666141210224137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, John J, Langford D, Walker E, Ward S, Rawls SM. Clavulanic acid enhances glutamate transporter subtype I (GLT-1) expression and decreases reinforcing efficacy of cocaine in mice. Amino Acids. 2016;48:689–696. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura O, Wee S, Specio SE, Koob GF, Pulvirenti L. Escalation of methamphetamine self-administration in rats: a dose-effect function. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0353-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyatkin EA, Kim AH, Wakabayashi KT, Baumann MH, Shaham Y. Effects of social interaction and warm ambient temperature on brain hyperthermia induced by the designer drugs methylone and MDPV. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:436–445. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyatkin EA, Lenoir M. Intravenous saline injection as an interoceptive signal in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217:387–396. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2294-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis JM, Janowsky A. Neuroimmune basis of methamphetamine toxicity. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2014;118:165–197. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801284-0.00007-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London ED, Kohno M, Morales AM, Ballard ME. Chronic methamphetamine abuse and corticostriatal deficits revealed by neuroimaging. Brain Res. 2015;1628:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Arnau R, Martinez-Clemente J, Pubill D, Escubedo E, Camarasa J. Serotonergic impairment and memory deficits in adolescent rats after binge exposure of methylone. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:1053–1063. doi: 10.1177/0269881114548439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Arnau R, Martinez-Clemente J, Rodrigo T, Pubill D, Camarasa J, Escubedo E. Neuronal changes and oxidative stress in adolescent rats after repeated exposure to mephedrone. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luethi D, Liechti ME, Krahenbuhl S. Mechanisms of hepatocellular toxicity associated with new psychoactive synthetic cathinones. Toxicology. 2017;387:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JC. Psychoactive substances - some new, some old: a scan of the situation in the U.S. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miotto K, Striebel J, Cho AK, Wang C. Clinical and pharmacological aspects of bath salt use: a review of the literature and case reports. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morici JF, Bekinschtein P, Weisstaub NV. Medial prefrontal cortex role in recognition memory in rodents. Behav Brain Res. 2015;292:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motbey CP, Karanges E, Li KM, Wilkinson S, Winstock AR, Ramsay J, Hicks C, Kendig MD, Wyatt N, Callaghan PD, McGregor IS. Mephedrone in adolescent rats:residual memory impairment and acute but not lasting 5-HT depletion. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutschler NH, Miczek KA. Withdrawal from a self-administered or non-contingent cocaine binge: differences in ultrasonic distress vocalizations in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1998;136:402–408. doi: 10.1007/s002130050584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura KJ, Ortiz JB, Conrad CD. Antagonizing the GABAA receptor during behavioral training improves spatial memory at different doses in control and chronically stressed rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2017;145:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Martins SS, Su MK, Ompad DC. Self-reported use of novel psychoactive substances in a US nationally representative survey: prevalence, correlates, and a call for new survey methods to prevent underreporting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira RB, Andrade PB, Valentao P. A comprehensive view of the neurotoxicity mechanisms of cocaine and ethanol. Neurotox Res. 2015;28:253–267. doi: 10.1007/s12640-015-9536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin S, Stavro K, Rizkallah E, Pelletier J. Cocaine and cognition: a systematic quantitative review. J Addict Med. 2014;8:368–376. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Ramsey LA, Schwendt M, McGinty JF, See RE. Methamphetamine-induced changes in the object recognition memory circuit. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Schwendt M, McGinty JF, Olive MF, See RE. Loss of object recognition memory produced by extended access to methamphetamine self-administration is reversed by positive allosteric modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:782–792. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Hernandez H, Cuevas E, Lantz SM, Imam SZ, Rice KC, Gannon BM, Fantegrossi WE, Paule MG, Ali SF. 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) induces cytotoxic effects on human dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells. J Drug Alcohol Res. 2016a;5:235991. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Hernandez H, Cuevas E, Lantz SM, Rice KC, Gannon BM, Fantegrossi WE, Gonzalez C, Paule MG, Ali SF. Methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) induce differential cytotoxic effects in bovine brain microvessel endothelial cells. Neurosci Lett. 2016b;629:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross EA, Reisfield GM, Watson MC, Chronister CW, Goldberger BA. Psychoactive "bath salts" intoxication with methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Am J Med. 2012;125:854–858. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Caroni P. Selective neuronal vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases: from stressor thresholds to degeneration. Neuron. 2011;71:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Thorndike EB, Goldberg SR, Lehner KR, Cozzi NV, Brandt SD, Baumann MH. Reinforcing and neurochemical effects of the "bath salts" constituents 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylcathinone (methylone) in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016;233:1981–1990. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC. Development and application of novel histochemical tracers for localizing brain connectivity and pathology. Brain Res. 2016;1645:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC, Stowers CC, Scallet AC, Xu L. Fluoro-Jade C results in ultra high resolution and contrast labeling of degenerating neurons. Brain Res. 2005;1035:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scofield MD, Trantham-Davidson H, Schwendt M, Leong KC, Peters J, See RE, Reichel CM. Failure to recognize novelty after extended methamphetamine self-administration results from loss of long-term depression in the perirhinal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:2526–2535. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortall SE, Macerola AE, Swaby RT, Jayson R, Korsah C, Pillidge KE, Wigmore PM, Ebling FJ, Green AR, Fone KC, King MV. Behavioural and neurochemical comparison of chronic intermittent cathinone, mephedrone and MDMA administration to the rat. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, Schramm Y, Dieu LH, Huwyler J, Chaboz S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:458–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmler LD, Liechti ME. Interactions of cathinone NPS with human transporters and receptors in transfected cells. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;32:49–72. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani SMA, Ekhtiari H, Cadet JL. Drug-induced neurotoxicity in addiction medicine: from prevention to harm reduction. Prog Brain Res. 2016;223:19–41. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranahan AM, Mattson MP. Selective vulnerability of neurons in layer II of the entorhinal cortex during aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Plast. 2010;2010:108190. doi: 10.1155/2010/108190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twining RC, Bolan M, Grigson PS. Yoked delivery of cocaine is aversive and protects against the motivation for drug in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:913–925. doi: 10.1037/a0016498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente MJ, Araujo AM, Silva R, Bastos Mde L, Carvalho F, Guedes de Pinho P, Carvalho M. 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV): in vitro mechanisms of hepatotoxicity under normothermic and hyperthermic conditions. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90:1959–1973. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1653-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente MJ, Bastos ML, Fernandes E, Carvalho F, Guedes de Pinho P, Carvalho M. Neurotoxicity of β-keto amphetamines: deathly mechanisms elicited by methylone and MDPV in human dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:850–859. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Yu S, Simonyi A, Sun GY, Sun AY. Kainic acid-mediated excitotoxicity as a model for neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;31:3–16. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton EC, Brown MW. Neural circuitry for rat recognition memory. Behav Brain Res. 2015;285:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson LR, Kufahl PR, Nemirovsky NE, Sewalia K, Grabenauer M, Thomas BF, Marusich JA, Wegner S, Olive MF. Potent rewarding and reinforcing effects of the synthetic cathinone 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) Addict Biol. 2014;19:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson LR, Olive MF. Synthetic cathinones and their rewarding and reinforcing effects in rodents. Adv Neurosci. 2014;2014:209875. doi: 10.1155/2014/209875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson LR, Olive MF. Reinforcing effects of cathinone NPS in the intravenous drug self-administration paradigm. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;32:133–143. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee S, Specio SE, Koob GF. Effects of dose and session duration on cocaine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1134–1143. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Mitcheson LR, Deluca P, Davey Z, Corazza O, Schifano F. Mephedrone, new kid for the chop? Addiction. 2011;106:154–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. Object recognition memory: neurobiological mechanisms of encoding, consolidation and retrieval. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1055–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Seeburg PH. A complex mosaic of high-affinity kainate receptors in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3582–3598. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03582.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszak J, Andrzejczak D, Woldan-Tambor A, Zawilska JB. Cytotoxic activity of pyrovalerone derivatives, an emerging group of psychostimulant designer cathinones. Neurotox Res. 2016;30:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s12640-016-9640-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright TH, Cline-Parhamovich K, Lajoie D, Parsons L, Dunn M, Ferslew KE. Deaths involving methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in Upper East Tennessee. J Forens Sci. 2013;58:1558–1562. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]