Abstract

Background

Patients with dementia form an increasing proportion of those entering hospice care. Little is known about the types of hospices serving patients with dementia and the patterns of hospice use, including timing of hospice disenrollment between patients with and without dementia.

Objectives

To characterize the hospices that serve patients with dementia, to compare patterns of hospice disenrollment for patients with dementia and without dementia, and to evaluate patient-level and hospice-level characteristics associated with hospice disenrollment.

Methods

We used data from a longitudinal cohort study (2008–2011) of Medicare beneficiaries (n = 149,814) newly enrolled in a national random sample of hospices (n = 577) from the National Hospice Survey and followed until death (84% response rate).

Results

A total of 7328 patients (4.9%) had a primary diagnosis of dementia. Hospices caring for patients with dementia were more likely to be for-profit, larger sized, provide care for more than 5 years, and serve a large (>30%) percentage of nursing home patients. Patients with dementia were less likely to disenroll from hospice in conjunction with an acute hospitalization or emergency department visit and more likely to disenroll from hospice after long enrollment periods (more than 165 days) as compared with patients without dementia. No significant difference was found between patients with and without dementia for disenrollment after shorter enrollment periods (less than 165 days). In the multivariable analyses, patients were more likely to be disenrolled after 165 days if they were served by smaller hospices and hospices that served a small percentage of nursing home patients.

Conclusion

Patients with dementia are significantly more likely to be disenrolled from hospice following a long enrollment period compared with patients without dementia. As the number of individuals with dementia choosing hospice care continues to grow, it is critical to address potential barriers to the provision of quality palliative care for this population near the end of life.

Keywords: Hospice care, dementia, palliative care, cross-sectional, United States

Dementia is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and the number of individuals dying of dementia is steadily increasing.1 Between 2000 and 2015, the number of individuals who died from Alzheimer disease increased by 123% (or 61,000 individuals).2 An increasing number of people with dementia are enrolling with hospice at the end of life and they represent the fastest growing group of hospice users.3 As codified under Medicare, hospice provides a package of clinical and psychosocial services to Medicare beneficiaries who are considered to have a terminal diagnosis (defined as a life expectancy of ≤6 months) and who are willing to forgo Medicare coverage for curative treatment.4 In the late 1990s, only 3.3% of those who used hospice had a primary diagnosis of dementia.5 By 2014, an estimated 14.8% of hospice users had a primary diagnosis of dementia. Although an increasing body of evidence has identified the complexity of caring for those with dementia at the end of life,6,7 little is known about the types of hospices providing care for them.

Evidence suggests that patterns of hospice use for individuals with a diagnosis of dementia differ from those with other diseases. They tend to be either enrolled in hospice for a very short (1 week or less) or a very long (longer than 6 months) period of time.8–11 Moreover, patients with dementia have higher rates of disenrollment from hospice before death compared with others.12 In the context of the current regulatory environment in the United States, patients may be disenrolled from hospice for 4 reasons: (1) if their condition stabilizes or improves over time and the certifying physician is unable to recertify a prognosis of 6 months or less; (2) if the patient moves out of the hospice service area or is admitted to a hospital that does not have a hospice contract; (3) if a patient or surrogate desires to resume curative care; or (4) if a patient or family no longer wants hospice care.13 Disenrollment from hospice represents a disruption in continuity of care and has been associated with higher rates of subsequent hospitalizations and a greater likelihood of emergency department (ED) use, intensive care unit admission, and hospital death.14,15 Although our prior work has identified distinct patterns of hospice disenrollment and their associations with intensity of care at the end of life for patients with cancer,16 there are no studies to our knowledge that evaluate the patterns of disenrollment among a large national sample of individuals with dementia.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were (1) to characterize hospices that serve patients with a diagnosis of dementia (both as the primary diagnosis or as a comorbidity), (2) to compare patterns of hospice disenrollment for patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia and patients with a primary diagnosis other than dementia, and (3) to evaluate patient-level and hospice-level characteristics associated with different patterns of hospice disenrollment. Characterizing the types of hospices that care for patients with dementia and examining the patterns of hospice disenrollment for patients with and without dementia is a first step toward identifying hospices with “best practices” that may be replicated to provide higher-quality hospice care for this growing population.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

We conducted a longitudinal cohort study of Medicare beneficiaries cared for by a national random sample of hospices that responded to the National Hospice Survey. As described elsewhere,17 data from the 577 hospices included in the National Hospice Survey data were linked to Medicare claims for beneficiaries newly enrolled in those hospices in 2008–2009 and followed until their death (2008–2010). Patients who were not eligible for both Medicare Parts A and B (n = 2111), who were enrolled in a managed care organization (n = 46,567), or who were younger than 66 years (n = 15,003) were excluded from our analyses. The final sample included a total of 149,814 hospice enrollees who were cared for by a total of 577 hospices.

Measurements

Dementia diagnosis and patient characteristics

A primary diagnosis of dementia was identified on Medicare hospice claims data and defined based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (290.0–290.4x, 294.0, 294.1, 294.8, 331.0–331.2, and 331.7). The following patient demographic and clinical characteristics were also obtained from Medicare hospice claims data: age (categorized as 65–84 years and 85 years and older), sex, and reported race/ethnicity (white or other), and the count of chronic conditions (fewer than 5 vs more than 5). Information regarding the number of chronic conditions was obtained by examining all Medicare hospital inpatient and outpatient claims for each individual for the 12 months before their hospice enrollment.

Hospice characteristics

The following hospice agency characteristics were obtained from the National Hospice Survey and included in our analyses given their association with patterns of hospice care16,18: hospice ownership, size (defined as the number of patients per day in the past 12 months), whether or not the hospice has an open access policy (ie, whether a hospice offers palliative services to non-hospice patients), years of providing hospice care (measured as <5 years or ≥5 years), whether the hospice was part of a chain of hospices, proportion of patients served in the nursing home (categorized as <10%, 10%–20%, 20%–30% and >30%, based on the quartile values of the distribution), urban/rural location (measured as whether the hospice’s county had ≥1 million population) and census region of the hospice.

Patterns of hospice use

We measured hospice length of stay for each patient using the Medicare hospice claims data. Length of hospice stay from hospice enrollment to death or disenrollment was included in all models as a potential confounder of the association between hospice characteristics and disenrollment, based on our prior work.3,4,16 Consistent with prior work, we identified individuals as having disenrolled from hospice if: (1) they had only 1 hospice enrollment period and the patient status indicator code on the final hospice claim indicated that the patient was discharged (rather than died) and there was no date of death on the final hospice claim; or (2) if they had >1 hospice enrollment period. We categorized patterns of hospice disenrollment as (1) disenrollment in conjunction with an acute hospitalization or ED visit, (2) disenrollment following long hospice stays (defined as more than 165 days), and (3) disenrollment following hospice stays shorter than 165 days. Disenrollment from hospice in conjunction with an acute hospitalization (including intensive care unit admission) or ED visit was defined as hospice discharge within 1 day of an acute hospitalization or ED visit. We categorized hospice disenrollment after a long stay as being a stay that is more than 165 days because hospice enrollees with stays 180 days or more are required by the Medicare Hospice Benefit to be re-certified as terminal, and this recertification (or disenrollment) is likely to occur within 2 weeks of the 180-day period. We performed sensitivity analyses with alternative cutoffs of 160 days, 170 days, and 180 days, and results are not materially different.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the characteristics of our sample by patient demographic and clinical characteristics and hospice characteristics. We compared the prevalence of patient and hospice characteristics as well as the patterns of hospice disenrollment for the dementia and non-dementia group using χ2 tests. To characterize the hospices that serve patients with dementia, we examined the associations between hospice-level characteristics and the percentage of any patients with dementia they serve (both patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia and patients with a coexisting diagnosis of dementia), using generalized linear models. We estimated separate multivariable models for the 3 patterns of hospice disenrollment. For this, multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the associations between patient and hospice characteristics and the 3 patterns of disenrollment, compared with patients who remained with hospice until death. All tests were performed using techniques to account for the clustering of patient observations within hospices. A 2-tailed P < .05 was used to define statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM Statistics SPSS, version 24 (IBM Corp, Chicago, IL) and SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Study Population

Our sample consisted of 149,814 patients who were newly enrolled with 1 of the 577 hospices that responded to the National Hospice Survey. Of these, 7328 patients (4.9%) had a primary diagnosis of dementia. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the samples of patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia and patients with a primary diagnosis other than dementia. The mean length of stay in hospice for people with a primary diagnosis of dementia was 112 days compared with 74 days for patients with a primary diagnosis other than dementia.

Table 1.

Patient and Hospice Characteristics

| Patients With Primary Diagnosis of Dementia, n = 7328 | Patients With Primary Diagnosis Other Than Dementia, n = 142,486 | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | n (%) | ||

| Age, y | † | ||

| 65–84 | 2678 (36.5) | 77,977 (54.7) | |

| ≥85 | 4650 (63.5) | 64,509 (45.3) | |

| Sex | † | ||

| Female | 5250 (71.6) | 83,710 (58.7) | |

| Male | 2078 (28.4) | 58,776 (41.3) | |

| Ethnicity | † | ||

| White | 6348 (86.6) | 127,618 (89.6) | |

| Other | 980 (13.4) | 14,868 (10.4) | |

| Count of chronic conditions | † | ||

| <5 | 3691 (50.4) | 74,991 (52.6) | |

| ≥5 | 3637 (49.6) | 67,495 (47.4) | |

| Length of stay in hospice | † | ||

| Mean number of days | 111.9 | 74.13 | |

| Hospice characteristics | n (%) | ||

| Hospice ownership | † | ||

| For-profit | 2776 (38) | 42,713 (30.3) | |

| Nonprofit | 4521 (62) | 98,280 (69.7) | |

| Hospice size (average no. of patients per day) | † | ||

| <20 | 191 (2.6) | 7509 (5.3) | |

| 20–49 | 611 (8.3) | 17,706 (12.4) | |

| 50–99 | 1411 (19.3) | 33,474 (23.5) | |

| ≥100 | 5115 (69.8) | 83,797 (58.8) | |

| Years of providing hospice care | † | ||

| Hospice provides care <5 years | 1270 (17.4) | 18,816 (13.2) | |

| Hospice provides care ≥5 years | 6033 (82.6) | 123,366 (86.8) | |

| Hospice is member of a chain | † | ||

| Yes | 2353 (32.1) | 35,144 (24.7) | |

| No | 4975 (67.9) | 107,342 (75.3) | |

| Open acces policy | † | ||

| Yes | 3923 (53.7) | 68,926 (48.5) | |

| No | 3377 (46.3) | 73,097 (51.5) | |

| Percentage of nursing home patients served by the hospice | † | ||

| <10% | 571 (8.2) | 18,303 (13.5) | |

| 10–20% | 1775 (25.6) | 37,866 (27.9) | |

| 20–30% | 1173 (16.9) | 18,381 (13.5) | |

| >30% | 3407 (49.2) | 61,406 (45.2) | |

| Location | † | ||

| Rural/Suburban | 512 (7) | 17,742 (12.5) | |

| Urban | 6816 (93) | 124,744 (87.5) | |

| Region | † | ||

| New England | 259 (3.5) | 5,479 (3.8) | |

| Middle Atlantic | 826 (11.3) | 12,520 (8.8) | |

| Eastern North Central | 1361 (18.6) | 28,686 (20.1) | |

| Western North Central | 332 (4.5) | 11,253 (7.9) | |

| South Atlantic | 2083 (28.4) | 34,234 (24) | |

| Eastern South Central | 574 (7.8) | 13,059 (9.2) | |

| Western South Central | 949 (13.0) | 16,170 (11.3) | |

| Mountain | 281 (3.8) | 8019 (5.6) | |

| Pacific | 663 (9.0) | 13,072 (9.2) |

Pearson χ2 testing for differences between the 2 groups.

P < .01.

Variation Among Hospice Providers in the Percentage of Patients With Dementia They Serve

The median number of patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia who were cared for by hospices in our sample was 5 (with an interquartile range of 2 to 15). A total of 388 (or 67.24% of) hospices cared for patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia. In total, 576 hospices (99%) cared for patients with any diagnosis of dementia (either a primary or coexisting diagnosis). The median number of patients with any diagnosis of dementia who were cared for by hospices in our sample was 56 (with an interquartile range of 22 to 133). The variation in percentage of patients with any diagnosis of dementia (either a primary or coexisting diagnosis) being served among hospice providers is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Average Proportion of Hospices’ Patient Population With Primary or Comorbid Dementia or Alzheimer Disease (n = 577 Hospices)

| Hospice Characteristics | Proportion of Patient Population With Dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

| Hospice ownership | ||||

| For-profit | 52.4 | 50.1 | ||

| Nonprofit | 41.3 | * | 43.3 | * |

| Hospice size (average no. patients per day) | ||||

| <20 | 41.9 | 43.3 | ||

| 20–49 | 46.8 | * | 46.5 | † |

| 50–99 | 49.1 | * | 48.1 | * |

| ≥100 | 48.6 | * | 48.6 | * |

| Open access policy | ||||

| Yes | 44.6 | 46.1 | ||

| No | 47.1 | 47.0 | ||

| Years of providing hospice care | ||||

| Hospice provides care <5 years | 52.6 | 50.2 | ||

| Hospice provides care ≥5 years | 43.5 | * | 44.9 | * |

| Hospice is member of a chain | ||||

| Yes | 52.3 | 47.1 | ||

| No | 44.6 | * | 46.5 | |

| Percentage of nursing home patients served by the hospice | ||||

| <10% | 40.4 | ref | 41.5 | ref |

| 10%–20% | 43.8 | † | 43.5 | |

| 20%–30% | 45.1 | † | 46.6 | * |

| >30% | 52.6 | * | 52.0 | * |

| Location | ||||

| Rural/Suburban | 39.8 | 42.3 | ||

| Urban | 49.4 | * | 48.4 | * |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 49.3 | ref | 51.1 | ref |

| Midwest | 43.8 | * | 44.3 | * |

| South | 48.7 | 47.6 | ||

| West | 43.0 | * | 45.1 | * |

P < .01.

P < .05.

Patterns of Hospice Disenrollment for Patients With and Without Dementia

A total of 20,212 patients (13.5%) disenrolled from hospice before death. The median number of days from hospice enrollment to disenrollment was 135 days for patients with dementia and 80 days for patients without dementia. The median number of days from hospice disenrollment to death was 154 days (approximately 5 months) for patients with dementia and 87 days for patients without a primary diagnosis of dementia.

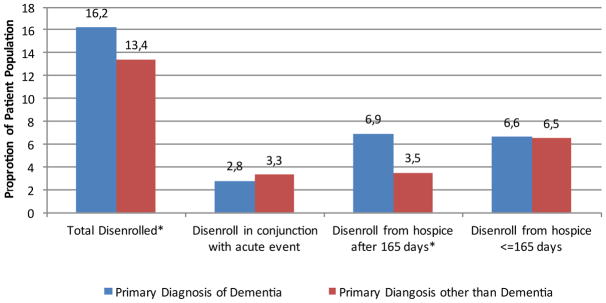

The proportions of patients with and without a primary diagnosis of dementia by hospice disenrollment pattern are shown in Figure 1. Among patients with a primary diagnosis, 16.2% disenrolled from hospice, whereas this occurred for 13.4% of patients with a primary diagnosis other than dementia. The unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) show that patients with dementia were less likely to remain with hospice until death (OR 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.66–0.94) and more likely to disenroll from hospice after a long hospice stay (OR 2.01; 95% CI 1.74–2.31) as compared with patients with a primary diagnosis other than dementia (data not shown in tables). The multivariable results show no significant difference between patients with and without a primary diagnosis of dementia in overall disenrollment from hospice; however, differences were observed within the different patterns of disenrollment (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Dementia status and hospice disenrollment patterns. Column percentages; Pearson χ2 testing for differences among the 4 different patterns of disenrollment: (1) patients who remained with hospice until death, (2) patients who disenrolled from hospice in conjunction with an acute event, (3) patients who disenrolled from hospice >165 days, and (4) patients who disenrolled from hospice ≤165 days. *P < .05.

Table 3.

Patient and Hospice Characteristics Associated With Hospice Disenrollment Patterns, n = 149,814

| Overall Disenrollment From Hospice* | Patterns of Hospice Disenrollment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Patients Who Disenrolled in Conjunction With an Acute Event* | Patients Who Disenrolled >165 Days† | Patients Who Disenrolled ≥165 Days* | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Primary diagnosis of dementia | ||||

| Yes | 1.04 (0.92–1.16) | 0.78 (0.65–0.94)‡ | 1.25 (1.08–1.46)† | 0.97 (0.86–1.09) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Age, y | ||||

| 65–84 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| ≥85 | 0.88 (0.84–0.91)‡ | 0.67 (0.62–0.72)‡ | 0.92 (0.86–0.98)‡ | 0.91 (0.87–0.96)‡ |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1.06 (1.02–1.10)‡ | 0.97 (0.91–1.04) | 1.14 (1.06–1.23)‡ | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) |

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 0.70 (0.64–0.75)‡ | 0.49 (0.44–0.54)‡ | 0.86 (0.76–0.97)‡ | 0.78 (0.71–0.85)‡ |

| Other | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Count of chronic conditions | ||||

| <5 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| ≥5 | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 1.17 (1.10–1.26)‡ | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 0.90 (0.86–0.95)‡ |

| Hospice characteristics | ||||

| Hospice ownership | ||||

| For-profit | 1.38 (1.23–1.55)‡ | 2.15 (1.79–2.59)‡ | 0.97 (0.83–1.14) | 1.24 (1.10–1.40)‡ |

| Nonprofit | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Hospice size (average no. patients per day) | ||||

| <20 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 20–49 | 1.01 (0.85–1.19) | 1.10 (0.85–1.43) | 1.04 (0.81–1.33) | 0.95 (0.78–1.16) |

| 50–99 | 0.84 (0.70–0.99)‡ | 0.90 (0.70–1.16) | 0.80 (0.63–1.03) | 0.83 (0.68–1.00) |

| ≥100 | 0.75 (0.63–0.91)‡ | 0.83 (0.61–1.13) | 0.64 (0.49–0.82)‡ | 0.77 (0.63–0.94)‡ |

| Open access policy | ||||

| Yes | 1.01 (0.90–1.14) | 0.95 (0.77–1.16) | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 1.03 (0.91–1.17) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Years of providing hospice care | ||||

| Hospice provides care <5 years | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Hospice provides care >5 years | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) | 1.02 (0.87–1.20) | 0.91 (0.79–1.04) |

| Percentage of nursing home patients served by the hospice | ||||

| <10% | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 10%–20% | 0.95 (0.83–1.10) | 0.93 (0.70–1.22) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) |

| 20%–30% | 0.78 (0.64–0.95)‡ | 0.65 (0.49–0.90)‡ | 0.75 (0.56–0.99)‡ | 0.83 (0.69–1.00) |

| >30% | 0.74 (0.62–0.88)‡ | 0.51 (0.41–0.71)‡ | 0.76 (0.60–0.96)‡ | 0.80 (0.67–0.95)‡ |

| Location | ||||

| Rural/Suburban | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Urban | 0.88 (0.78–1.00) | 0.82 (0.66–1.02) | 0.98 (0.82–1.16) | 0.88 (0.78–0.98)‡ |

| Region | ||||

| North East | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Midwest | 0.66 (0.55–0.78)‡ | 0.45 (0.29–0.70)‡ | 0.75 (0.60–0.94)‡ | 0.77 (0.66–0.90)‡ |

| South | 0.82 (0.67–1.00) | 0.64 (0.41–0.99)‡ | 0.70 (0.55–0.90)‡ | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) |

| West | 0.85 (0.70–1.05) | 0.53 (0.31–0.88)‡ | 0.74 (0.54–1.01) | 1.13 (0.96–1.32) |

Note. Bold values are statistically significant P < .05.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

The comparison group for the hospice disenrollment patterns are patients who remained with hospice until death.

Model 1, Model 2, and Model 4 control for patients’ total length of stay in hospice.

Model 3 only includes patients with a total length of stay >165 days.

P < .05.

Hospice disenrollment in conjunction with an acute hospitalization or ED visit

Patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia were less likely to disenroll from hospice in conjunction with an acute hospitalization or ED visit (OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.66–0.94) as compared with patients with a primary diagnosis other than dementia. All patients were more likely to be disenrolled in conjunction with an acute event if they were served by for-profit hospices (OR 2.15; 95% CI 1.79–2.59). They were less likely to be disenrolled in conjunction with an acute hospitalization or ED visit when they were served by a hospice serving a larger percentage (>30%) of nursing home patients (OR 0.51; 95% CI 0.41–0.71).

Hospice disenrollment after long hospice stay

Patients with dementia were more likely to be disenrolled from hospice after 165 days (OR 1.25; 95% CI 1.08–1.46) as compared with patients with a primary diagnosis other than dementia. In general, if patients were served by larger hospices taking care of more than 100 patients per day on average (OR 0.64; 95% CI 0.49–0.82) and by hospices who take care of a larger percentage (>30%) of nursing home patients (OR 0.76; 95% CI 0.60–0.96), they were less likely to be disenrolled after a long hospice stay.

Hospice disenrollment after hospice stay shorter than 165 days

No significant difference was found between patients with and without dementia for being disenrolled from hospice before 165 days. Patients were more likely to be discharged from hospice before 165 days if they were served by for-profit hospices (OR 1.24; 95% CI 1.10–1.40). Patients were less likely to disenroll before 165 days in hospices that serve a larger percentage of nursing home patients (OR 0.80; 95% CI 0.67–0.95), hospices located in an urban area (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.67–0.95) and hospices located in the northeast region of the United States (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.66–0.90).

Discussion

The proportion of patients with dementia cared for by hospices varies, with some hospices having no patients with dementia enrolled and others providing care for more than 500 patients with dementia. Patients in hospice with a primary diagnosis of dementia are less likely to be disenrolled from hospice in conjunction with an acute event compared with hospice enrollees with other primary diagnoses. Hospice patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia are significantly more likely to be disenrolled following a long length of stay in hospice.

The finding that for-profit hospices serve larger proportions of patients with dementia may be driven by the fact that hospice enrollees with dementia tend to have longer hospice enrollment periods. For-profit hospices are known to enroll higher volumes of patients with noncancer diagnoses.19,20 These diagnoses are associated with longer lengths of stay in hospice, which are known to be more profitable for hospices.21 However, recent efforts to reform Medicare’s hospice benefit increased the hospice reimbursement for the first days and reduced the reimbursement for the remainder of the enrollment period, to more accurately reflect hospice costs. This means the compensation for long enrollment periods is reduced, which might address the concern that some hospices follow a profit-maximization strategy by enrolling patients who are more likely to have long enrollments, including those with dementia, but future research is needed.22 Our finding that larger hospices and hospices older than 5 years serve higher proportions of patients with dementia might be explained by the fact that they have greater experience in service delivery for this population compared with small or newer hospices. Previous work has shown that programs serving patients with a secondary diagnosis of dementia are also more likely to enroll patients with dementia as a primary diagnosis, indicating that a dementia condition itself is not a major barrier to service delivery.23 Patients with dementia form an increasing proportion of those enrolling with hospice at the end of life.3 It is therefore important that all hospice providers are equipped to meet the specific challenges associated with caring for this growing population, as referral to hospice presents an opportunity to improve patients’ care at the end of life.7,24,25

The results of this study also show that the patterns of disenrollment differ for patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia and patients with a primary diagnosis other than dementia. We found that disenrollment from hospice in conjunction with an acute hospitalization or ED visit was less likely to occur for patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia compared with others. A discharge from hospice in conjunction with an acute event can sometimes be attributed to a scenario in which patients need inpatient services and the hospice was unable to provide general inpatient care because of the absence of a contract with the hospital. However, these discharges may also represent a hospice’s effort to avoid the costs of a hospitalization related to the terminal illness.26 Previous research has shown that individuals in hospice with dementia are less likely than individuals in hospice with other terminal diagnoses to undergo burdensome transitions between care settings,27,28 which might be explained by the fact that patients with dementia are less able to communicate their symptoms, such as pain.6,27 Also, many patients with dementia in hospice live in nursing homes and previous research has shown that transitions between care settings in the last months of life are less frequent among patients residing in nursing homes than among patients residing at home.29

Patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia were more likely to be disenrolled after a long hospice stay. Patients in hospice with a diagnosis of dementia have been found to have significantly longer duration of hospice care likely due to the difficulty of prognostication for those with a primary diagnosis of dementia compared with other diseases.30 We also found, however, that half of all patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia who disenrolled from hospice died within 5 months of hospice disenrollment, suggesting that the Medicare Hospice Benefit may not be the right fit for people with dementia.7 Home-based palliative care models outside of the Medicare Hospice Benefit that do not require a predictable terminal prognosis may better align with the needs of those with a primary diagnosis of dementia who desire home-based palliative care.

This is the first study to characterize the hospices serving patients with dementia and to evaluate patterns of disenrollment among a large national sample of individuals with dementia in the United States. This study also has limitations. First, these data were collected from 2008 through 2010 and thus may not reflect the current hospice market. However, as our results are in line with other recent studies,2,3 we have no reason to believe that the patterns of hospice use have changed. Second, neither the National Hospice Survey data nor the Medicare hospice claims data include information regarding the reasons for patient disenrollment from hospice or how disenrollment from hospice is related to patient and family preferences for care. Third, our results may not be generalizable to the approximately 7% of hospices in the United States that do not participate in the Medicare program, hospice users who are not Medicare beneficiaries, and hospice users who are enrolled in managed care organizations.

Conclusion

As the number of individuals with dementia enrolling with hospice at the end of life continues to grow, it is critical to ensure that all hospices have the right expertise in providing quality care for this frail and vulnerable patient group. Our results serve as a starting point for considering under what circumstances those with dementia should be disenrolled from hospice. Specifically, hospice-led disenrollment after a long stay may represent a discharge from hospice for “failure to die in a timely fashion” and thus limit hospice availability for patients with dementia near the end of life. Given evidence of poor outcomes for patients who disenroll from hospice, including higher rates of ED admissions and hospital death, hospice disenrollment rates and the reason for disenrollment should, at a minimum, be a reportable hospice quality measure alongside other reported relevant measures, such as the identification and management of symptoms (including pain), placement of a feeding tube, receipt of care concordant with patients’ preferences, and rate of burdensome transitions to acute care.12,27 Furthermore, our findings regarding the disenrollment patterns of those with dementia underscore the need for adequate guidance for hospices regarding the identification of patients appropriate for hospice admission. Hospice disenrollment may limit access to interdisciplinary palliative care services at the end of life for patients and their families. Future policy efforts should focus on providing high-quality palliative care based on patient and family need and not prognosis either through policy change enabling provision of non-hospice palliative care services in community settings or more flexible hospice eligibility criteria for patients with unpredictable prognosis, such as dementia.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:325–373. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldridge MD, Bradley EH. Epidemiology and patterns of care at the end of life: Rising complexity, shifts in care patterns and sites of death. Health Aff. 2017;36:1175–1183. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldridge MD, Canavan M, Cherlin E, Bradley EH. Has Hospice use changed? 2000–2010 utilization patterns. Med Care. 2015;53:95–101. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldridge MD, Schlesinger M, Barry CL, et al. National hospice survey results: For-profit status, community engagement, and service. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:500–506. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHPCO. [Accessed October 1, 2017];Facts and figures on hospice care NHPCO’s facts and figures. Available at: https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2016_Facts_Figures.pdf.

- 6.Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekelman DB, Black BS, Shore AD, et al. Hospice care in a cohort of elders with dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller SC, Lima J, Gozalo PL, Mor V. The growth of hospice care in U.S. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Colón-Emeric C, et al. Associations between published quality ratings of skilled nursing facilities and outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:188.e1–188.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SC, Lima JC, Mitchell SL. Hospice care for persons with dementia: The growth of access in US nursing homes. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25:666–673. doi: 10.1177/1533317510385809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Miller SC, et al. Hospice care for patients with dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unroe KT, Meier DE. Quality of hospice care for individuals with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1212–1214. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutner JS, Blake M, Meyer SA. Predictors of live hospice discharge: Data from the National Home and Hospice Care Survey (NHHCS) Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012;19:331–337. doi: 10.1177/104990910201900510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson MDA, Herrin J, Du Q, et al. Impact of hospice disenrollment on health care use and Medicare expenditures for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4371–4375. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Johnson KS, et al. Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163:987–993. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson MDA, Herrin J, Du Q, et al. Hospice characteristics and the disenrollment of patients with cancer. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:2004–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aldridge MD, Epstein AJ, Brody AA, et al. The impact of reported hospice preferred practices on hospital utilization at the end of life. Med Care. 2016;54:657–663. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson MDA, Barry C, Schlesinger M, et al. Quality of palliative care at US hospices. Med Care. 2011;49:803–809. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822395b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenz KA, Ettner SL, Rosenfeld KE, et al. Cash and compassion: Profit status and the delivery of hospice services. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:507–514. doi: 10.1089/109662102760269742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindrooth RC, Weisbrod BA. Do religious nonprofit and for-profit organizations respond differently to financial incentives? The hospice industry. J Health Econ. 2007;26:342–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, McCarthy EP. Association of hospice agency profit status with patient diagnosis, location of care, and length of stay. JAMA. 2011;305:472–479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teno JM, Bowman J, Plotzke M, et al. Characteristics of hospice programs with problematic live discharges. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:548–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanrahan P, Luchins DJ. Access to hospice programs in end-stage dementia: A national survey of hospice programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:56–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller SC, Lima JC, Intrator O, et al. Palliative care consultations in nursing homes and reductions in acute care use and potentially burdensome end-of-life transitions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2280–2287. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gozalo PL, Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teno JM, Plotzke M, Gozalo P, Mor V. A national study of live discharges from hospice. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1121–1127. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albrecht JS, Gruber-Baldini AL, Fromme EK, et al. Quality of hospice care for individuals with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1060–1065. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang S-Y, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, et al. End-of-life care transition patterns of Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1406–1413. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penders YW, Van den Block L, Donker GA, et al. EURO IMPACT. Comparison of end-of-life care for older people living at home and in residential homes: A mortality follow-back study among GPs in the Netherlands. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65:e724–e730. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X687349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell D, Diamond EL, Lauder B, et al. Frequency and risk factors for live discharge from hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1726–1732. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]