Abstract

The Sphaeropleales are a dominant group of green algae, which contain species important to freshwater ecosystems and those that have potential applied usages. In particular, Raphidocelis subcapitata is widely used worldwide for bioassays in toxicological risk assessments. However, there are few comparative genome analyses of the Sphaeropleales. To reveal genome evolution in the Sphaeropleales based on well-resolved phylogenetic relationships, nuclear, mitochondrial, and plastid genomes were sequenced in this study. The plastid genome provides insights into the phylogenetic relationships of R. subcapitata, which is located in the most basal lineage of the four species in the family Selenastraceae. The mitochondrial genome shows dynamic evolutionary histories with intron expansion in the Selenastraceae. The 51.2 Mbp nuclear genome of R. subcapitata, encoding 13,383 protein-coding genes, is more compact than the genome of its closely related oil-rich species, Monoraphidium neglectum (Selenastraceae), Tetradesmus obliquus (Scenedesmaceae), and Chromochloris zofingiensis (Chromochloridaceae); however, the four species share most of their genes. The Sphaeropleales possess a large number of genes for glycerolipid metabolism and sugar assimilation, which suggests that this order is capable of both heterotrophic and mixotrophic lifestyles in nature. Comparison of transporter genes suggests that the Sphaeropleales can adapt to different natural environmental conditions, such as salinity and low metal concentrations.

Introduction

Chlorophyceae are genetically, morphologically, and ecologically diverse class of green algae1. The group is dominant, particularly in freshwater, and plays important roles in global ecosystems2. The Chlorophyceae are composed of five taxonomic orders: Sphaeropleales, Chlamydomonadales, Chaetophorales, Chaetopeltidales, and Oedogoniales1. The Sphaeropleales are a large group, and contain some of the most common freshwater species (e.g. Scenedesmus, Desmodesmus, Tetradesmus, and Raphidocelis)3,4, including some species used in applications such as bioassays and biofuel production. In particular, Raphidocelis subcapitata and Desmodesmus subspicatus are recommended for ecotoxicological bioassays by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (TG201, http://www.oecd.org/) because they have higher growth rates and greater sensitivity to various substances than other algae.

Genome evolution in the Sphaeropleales is little understood compared to that of the Chlamydomonadales. In the Chlamydomonadales, genomes of four species (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, C. eustigma, Gonium pectorale, and Volvox carteri f. nagariensis) have been sequenced and analyzed thus far5–8. Comparative genome analyses have provided great insights into the evolution of green algae traits, such as flagella5, multicellularity6,7, and sexual reproduction9. In contrast, genome analyses of the Sphaeropleales are rare; only three genomes, that of Monoraphidium neglectum10, Tetradesmus obliquus11, and Chromochloris zofingiensis12, have been sequenced. Furthermore, their comparative analyses have not been performed. The comparative analyses should provide insights into genome evolution of the Sphaeropleales and adaptation to different freshwater environments. M. neglectum contains large amounts of lipids under a wide range of pH and salt conditions, and thus shows potential for lipid production13. Its genome is 68 Mbp and encodes 16,761 proteins, including many genes related to carbohydrate metabolism and fatty acid biosynthesis, and indicates that the vegetative cells have diploid characters. T. obliquus, which was formerly classified as Acutodesmus obliquus or Scenedesmus obliquus, is a model organism in the Sphaeropleales for biofuel production and organellar genetics. Its nuclear genome is 109 Mbp11, but its detailed genome structure (i.e. gene models and annotations) has not been described. Recently, the nuclear genome of C. zofingiensis (=Chlorella zofingiensis) has been sequenced; the genome size is 58 Mbp and it encodes 15,274 proteins. In the case of organellar genomes, the mitochondrial genome has unusual codon usages (i.e. UAG for leucine, not as a stop codon, and UCA as a stop codon, not for serine)14,15, and a split cox2 (cox2a, and cox2b)16. The cox2b gene is located in the nuclear genome, and thus it appears to have been transferred to the nuclear genome via an endosymbiotic gene transfer (EGT)17. In the Chlamydomonadales, both cox2a and cox2b are in the nuclear genome; therefore, the genes of T. obliquus are thought to be an intermediate character in EGT18. These mitochondrial characters are conserved in the Sphaeropleales17,19. The plastid genomes of the Sphaeropleales have fewer structural variations than the Chlamydomonadales and the OCC clade (Oedogoniales, Chaetopeltidales, and Chaetophorales)20. Therefore, the group is interesting for studying organellar and nuclear genome evolution in green algae.

R. subcapitata NIES-35 was formerly known as Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata or ‘Selenastrum capricornutum’4. On the basis of 18S rRNA phylogeny, R. subcapitata belongs to the family Selenastraceae, order Sphaeropleales, but its phylogenetic position in the group has not been resolved4,21,22. Although well-resolved phylogenetic relationships have been recently reported for the Sphaeropleales, using plastid or mitochondrial genome-encoded proteins19,20,23,24, the organellar genomes of R. subcapitata have not been sequenced. In this study, we sequenced the nuclear, mitochondrial, and plastid genomes of R. subcapitata, and compared them to other Sphaeropleales species genomes to reveal genome evolution in the order based on well-resolved phylogenetic relationships and to understand their genetic background in relation to high sensitivity to chemicals (e.g. metals). The plastid and mitochondrial genomes provide insights into the phylogenetic relationships of R. subcapitata and complex evolutionary histories in the order Sphaeropleales. The nuclear genome of R. subcapitata is the most compact in this order, and comparison of proteins indicates that the Sphaeropleales can adapt to a variety of nutrient and environmental conditions.

Results and Discussion

Phylogenetic analyses

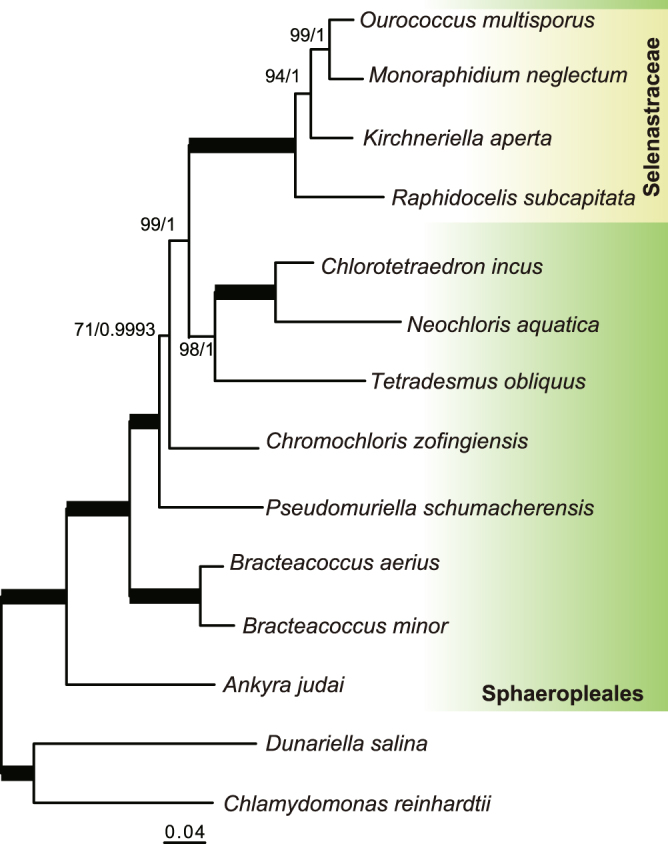

To infer the phylogenetic position of R. subcapitata within the Sphaeropleales, we performed phylogenetic analyses using two datasets: 55 plastid-encoded or 13 mitochondrion-encoded proteins (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. S1). In both trees, R. subcapitata formed a monophyletic group with the other Selenastraceae species, M. neglectum, Ourococcus multisporus, and Kirchneriella aperta. There was robust support (BP = 100 and BPP = 1.00) for inclusion of R. subcapitata in the Sphaeropleales; however, the topologies of the trees were different. The tree using plastid-encoded proteins resolves the phylogenetic relationships better than the mitochondrial tree because it had higher supporting values (BPs at all nodes ≥70) and was based on more amino acids than that based on mitochondrion-encoded proteins. In the plastid-based tree, R. subcapitata was the most basal lineage in the Selenastraceae (BP = 94 and BPP = 1.00) (Fig. 1). M. neglectum and O. multisporus were sister species showing robust support (BP = 99 and BPP = 1.00). The Selenastraceae was a sister group to T. obliquus, Neochloris aquatica, and Chlorotetraedron incus (BP = 99, BPP = 1.00). Chromochloris zofingiensis was monophyletic with the Selenastraceae, T. obliquus, N. aquatica, and C. incus, with moderate support (BP = 71, BPP = 0.9993). Therefore, C. zofingiensis was probably the most basal among the four species with available nuclear genomes of the Sphaeropleales.

Figure 1.

ML phylogenetic tree of the Sphaeropleales using 55 plastid-encoded proteins. The best tree was reconstructed using a concatenated dataset of 11,649 amino acids. Values at the nodes represent bootstrap supports (BP) of 200 replicates (right) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) (left). BP < 50 or BPP < 0.9 are not shown. Bold lines represent BP = 100 and BPP = 1.00.

Evolution of plastid and mitochondrial genomes

In the Sphaeropleales, 17 mitochondrial and 11 plastid genomes have been submitted so far to comparative analyses10,15,19,20,23–26. We sequenced the complete mitochondrial and plastid genomes of R. subcapitata and compared these sequences to those of other Sphaeropleales to reveal organellar genome evolution of the order, and particularly of the family Selenastraceae. The mitochondrial genome of R. subcapitata was circular and 44,268 bp in size (Supplementary Fig. S2a); this genome contained a large tandem repeat region with a 10-mer unit repeated at least 11 times at position 21,665. Protein-coding genes could be translated following the genetic code of the mitochondria of T. obliquus14. There were 13 conserved protein-coding genes (3 cytochrome oxygenases, 1 cytochrome b, 7 NADH dehydrogenase subunits, and 2 ATP synthase subunits), 6 fragmented rRNAs, and 28 tRNAs; as observed for other Sphaeropleales species, 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA were separated into two and four fragments, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Cox2 was split and its N-terminus (Cox2a) was encoded in the mitochondrial genome, similar to other mitochondrial genomes. Sphaeropleales species encode the C-terminus of Cox2 (Cox2b) in the nuclear genome17, and this was indeed the case in R. subcapitata (see below). R. subcapitata had 11 introns in cox1, cob, and rrl4, and 11 intronic open reading frames (ORFs), possibly encoding LAGLIDADG or GIY-YIG endonucleases. Except for an intron in rrl4, the introns of R. subcapitata were inserted at the same positions as that of at least one other Sphaeropleales species (Supplementary Fig. S3a–c), suggesting that they had the same origin. Selenastraceae species contained larger amounts of intronic sequences in the mitochondrial genomes than other Sphaeropleales species (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. S3a–c), suggesting that there was a gain in introns in a common ancestor of the Selenastraceae. ProgressiveMauve analysis27 was performed to reveal the genome arrangements in the Selenastraceae. The gene order in the mitochondrial genome of R. subcapitata was identical to those of K. aperta, O. multisporus, and M. neglectum; however, there was a divergent region in an intron of cob (Supplementary Fig. S4). Overall, R. subcapitata, K. aperta, and O. multisporus had genome structures with high similarities, although K. aperta possessed longer introns in rrl2 and rrl4. In contrast, M. neglectum had larger intergenic regions and introns (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. S4), which may have been caused by a secondary genome size expansion in this species.

Figure 2.

Size distributions of organellar genomes of Raphidocelis subcapitata and other Sphaeropleales species. (a) Mitochondrial genome of R. subcapitata. (b) Plastid genome of R. subcapitata. Blue, orange, and grey bars show the total sizes of coding sequences (CDSs), introns, and spacer regions, respectively.

The plastid genome of R. subcapitata was circularly mapped and 128,080 bp in size, including two 18,858 bp inverted repeats (IRs) (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Sixty-nine conserved protein-coding genes, 6 rRNAs, 30 tRNAs, and 7 intronic ORFs were found in the plastid genome (Supplementary Table S2). The IR had 1 psbA, 3 rRNAs, and 3 tRNAs. Two introns were inserted in psaA and 4 introns in 2 copies of rrl, all of which possessed an intronic ORF encoding LAGLIDADG endonuclease. Exceptionally, there was an ORF encoding maturase in an intergenic region between psbE and psaA-1; psaA was split into three fragments, which were dispersed in the genome, suggesting that they could be transcribed with trans-splicing, as in T. obliquus26. Among the Sphaeropleales species studied, M. homosphaera contained the smallest plastid genome (102.7 kbp), and R. subcapitata the second smallest, mainly because of small intergenic regions (Fig. 2b). Because the phylogenetic relationships between R. subcapitata and M. homosphaera are unclear, we cannot determine whether the genome reduction is derived. Of the three Selenastraceae species, R. subcapitata and K. aperta showed a completely conserved gene set (Supplementary Table S2), with K. aperta possessing a larger number of introns and intergenic regions (Fig. 2b). M. neglectum had an additional atpF in the IRs, one of which was fragmented; thus, it may be a pseudogene. Based on phylogenetic relationships, IRs increased in length in M. neglectum after branching in the Selenastraceae. The gene orders of M. neglectum and K. aperta were identical, but R. subcapitata contained an inversion of psbK–psbC (Supplementary Fig. S5), suggesting that this inversion occurred independently.

General features of the nuclear genome of R. subcapitata

We sequenced 4.1 Gbp reads using Illumina MiSeq. Based on assembly and scaffolding, we obtained 417 scaffolds (≥1 kbp). Major scaffolds (≥5 kb) were 51,162,697 bp in total (300 scaffolds) (Table 1). The assembly size was similar to the estimated genome size (46,790,751 bp), based on a k-mer analysis (Supplementary Fig. S6). To confirm the completeness of the genome, we performed BUSCO analysis, which assesses genome completeness to find the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCOs) in a target genome28. The analysis was based on the eukaryote dataset, and showed 91.7% complete BUSCOs, which was higher than those of C. zofingiensis, M. neglectum, and T. obliquus (84.5%, 58.5%, and 79.9%, respectively) (Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, 95.8% and 95.6% of the RNA-seq reads were mapped into ≥1 kb and ≥5 kb scaffolds, respectively. Therefore, we obtained a nearly complete genome for R. subcapitata. The 300 major scaffolds were annotated using the funannotate pipeline based on ab initio and transcripts-based gene prediction. Repeat sequences (12.45% of the major scaffolds) were masked, and most (10.5% of the major scaffolds) were simple repeats. At least 5 rRNAs, 46 tRNAs, and 13,383 protein-coding genes were predicted. Additionally, 11,902 protein-coding genes (88.9% of the prediction) were detected by RNA-seq. The remaining 11.1% of gene models were not mapped with the RNA-seq reads; therefore, they may be rarely expressed genes and some may be pseudogenes. The protein-coding genes contained 76,178 introns at a density of 5.7 introns per gene.

Table 1.

Statistical comparison of nuclear genomes of R. subcapitata, M. neglectum, T. obliquus, C. zofingiensis and C. reinhardtii.

| Raphidocelis subcapitata | Monoraphidium neglectum | Tetradesmus obliquus | Chromochloris zofingiensis ** | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii *** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | NIES-35 | SAG 48.87 | UTEX393 | SAG 211-14 | CC503 |

| Reference | This study | Bogen et al. (2013) | Carreres et al. (2017), this study | Roth et al. (2017) | Merchant et al. (2008) |

| Assembly size (Mbp) | 51 (≥5 kb) | 68 | 108 | 58 | 111 |

| Number of scaffolds | 417 (≥1 kb), 300 (≥5 kb) |

857 (>20 kb) | 1,368 | 19 (chromosomes) | 54 |

| L50 (Scaffolds) | 46 | 1,303 | 177 | — | 7 |

| N50 (Scaffolds, kbp) | 342 | 16 | 187 | chromosomes | 7,800 |

| GC% | 72 | 65 | 57 | 51 | 64 |

| Number of CDSs | 13,383 | 16,761 | 12,496 | 15,274 | 17,741 |

| Mean protein length (aa) | 561 | 348 | 452 | 427 | 736 |

| Mean intron length (bp) | 230 | 302 | 462 | 284 | 270 |

| Number of introns per gene | 5.7 | 4.0 | 7.8 | 4.0 | 7.5 |

| coding%* | 44.0 | 25.7 | 15.7 | 39**** | 35.2 |

*Only protein-coding genes.

**JGI v. 5.2.3.2.

***JGI v. 5.5.

****Roth et al. (2017).

The nuclear genome of R. subcapitata was smallest in the Sphaeropleales (Table 1). Thus far, the nuclear genomes of M. neglectum, T. obliquus, and C. zofingiensis have been sequenced10–12. The genomes differed greatly from that of R. subcapitata in size, gene number, coding capacity, and GC-content. T. obliquus has a 107.7 Mbp genome, which is nearly twice as large as that of R. subcapitata, but the two species possess a similar number of genes. The coding percentages of R. subcapitata and T. obliquus were 44.0% and 15.7%, respectively. These results suggest that the larger genome of T. obliquus is caused by a large amount of non-coding regions (i.e. intergenic regions and introns). The genomes of M. neglectum (68 Mbp) and C. zofingiensis (58 Mbp) were also smaller but with higher coding percentages (25.7% and 39%12, respectively) than that of T. obliquus. However, M. neglectum and C. zofingiensis possessed 16,761, and 15,274 genes, respectively, at least ~2,000 genes more than R. subcapitata and T. obliquus. We compared gene families, which were defined by TreeFam29, among R. subcapitata, M. neglectum, T. obliquus, and C. zofingiensis. Most of the families (58.2–69.8% of the total) were shared by them (Fig. 3a). C. zofingiensis had 4,063 gene families, ~300 more gene families than the others (Fig. 3b). However, only 296 unique gene families were found in C. zofingiensis, which was similar to that of the others (160–218 gene families) (Fig. 3a). Functional analyses using KEGG categories30 showed that most of the functions were shared in the Sphaeropleales (Fig. 3c). M. neglectum possessed the largest number of genes among the Sphaeropleales families considered in the study (Fig. 3b). Therefore, gene expansion in M. neglectum probably originated in the past as a complete or partial duplication of the genome. Bogen et al.10 reported that M. neglectum had a diploid character because their investigation of a ‘contig length vs. read count’ plot showed homozygous and heterozygous contigs. In this plot, contigs of homozygous loci have more than twice the read coverage than those of heterozygous loci31. However, such characters were not found in R. subcapitata, T. obliquus (Supplementary Fig. S7a,b), and C. zofingiensis12. Therefore, we consider that vegetative cells of the Sphaeropleales are basically haploid. The haploid character, and the small size and simplicity of the R. subcapitata genome are of great advantage for transformation and genome editing. Interestingly, GC-content of R. subcapitata was 71.6%, which was higher than that of M. neglectum, T. obliquus, and C. zofingiensis (Table 1). Roth et al.12 indicated that the high GC-content of several algae was associated with more fragmentary assemblies. However, the R. subcapitata genome had higher GC-content than M. neglectum and T. obliquus despite the less fragmentary assembly of R. subcapitata (Table 1; Supplementary Table S3). Therefore, the genome of R. subcapitata might have high GC-content in nature. Codon usage of R. subcapitata was highly biased; we found that although all codons were used, there was a greater proportion of GC at synonymous codons, e.g. cysteine was coded for by 20% UGU and 80% UGC codons (Supplementary Table S4). Additionally, the GC-content of transcripts (coding regions) in R. subcapitata was 74.6%, which was higher than that of spacer regions (66.2%). These results suggest that the GC bias is related to the high gene density and coding length of R. subcapitata. In mammalian species, it is known that high GC-content is positively correlated to gene density32 and coding length33.

Figure 3.

Comparison of gene families among Raphidocelis subcapitata, Monoraphidium neglectum, Tetradesmus obliquus, and Chromochloris zofingiensis. (a) Venn diagram of the gene families of R. subcapitata, M. neglectum, and T. obliquus. (b) The number and size of gene families. Gene families consisting of multiple genes are shown in red, grey, and orange according to their family size (two, three, and more than four, respectively). (c) Functional comparison of the genes according to KEGG classification.

Restricted endosymbiotic gene transfer of mitochondrial genes in the Sphaeropleales

Species in the Sphaeropleales have split cox2 (cox2a and cox2b) genes, with cox2a located in the mitochondrial genome and cox2b located in the nuclear genome, based on the difference in codon usage between the mitochondria and nucleus and the presence of spliceosomal introns. Because the Chlamydomonadales have both split cox2 genes in their nuclear genome16, the Sphaeropleales appear to show an intermediate trait of gene migration to the nucleus17.

To gain further insights into EGT from the mitochondrial genome in the Sphaeropleales, we searched for cox2b and nuclear mitochondrial DNA segments (NUMTs), which are nuclear sequences that are similar to the mitochondrial genome sequences. We found a cox2b gene in R. subcapitata, M. neglectum, and C. zofingiensis. T. obliquus possessed two copies of cox2b with N terminal sequences that differed from those reported previously17. All of the cox2b possessed a ~50 aa N-terminal extension, which was very similar to that of the Chlamydomonadales (Supplementary Fig. S8), strongly supporting the conclusion that cox2b migrated to the nucleus in a common ancestor of the Chlamydomonadales and Sphaeropleales17.

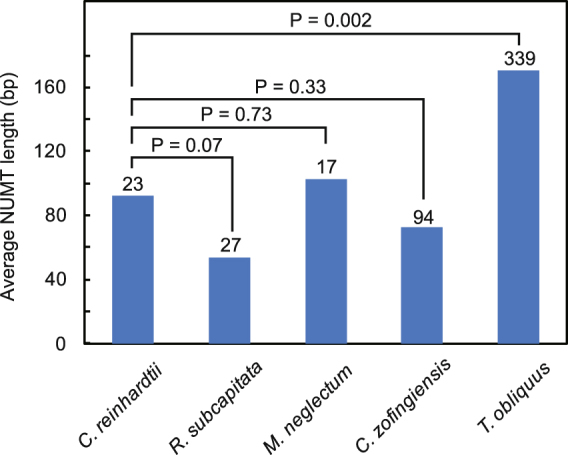

We also performed homology searching of the mitochondrial sequences against the nuclear sequences. We did not find mitochondrial-encoded genes in nuclear protein-coding genes; however, we found some NUMTs in intergenic regions or introns of the nuclear genomes. R. subcapitata possessed 27 NUMTs with 30–119 bp with 88–100% similarity (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S5), and M. neglectum possessed 17 NUMTs with 34–350 bp with 83–100% similarity. C. zofingiensis possessed 94 NUMTs, a greater number than in R. subcapitata and M. neglectum, with 31–279 bp with 82–100% similarity. These NUMT lengths were not significantly different from those in C. reinhardtii (P = 0.07–0.72, t-test) (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the Sphaeropleales and the Chlamydomonadales have similar amounts of ongoing mitochondrial DNA transfer to the nucleus. However, in the Sphaeropleales, cox2a has not been transferred to the nuclear genome; this might be caused by unusual codon usage in this order17. If the gene is transferred, it cannot be translated correctly to protein, and the DNA fragment may be eliminated immediately. Exceptionally, T. obliquus possessed many more NUMTs than the other Sphaeropleales, 339 NUMTs with 32–2,108 bp with 78–100% similarity (Supplementary Table S5), which were significantly larger in size than those of C. reinhardtii (P = 0.002, t-test) (Fig. 4). This may be explained by the lower gene density of T. obliquus. It had large spacer regions (3,647 bp on average) and introns (462 bp on average), therefore, it is likely that mitochondrial DNA fragments are transferred easily into the nucleus without disturbing genes.

Figure 4.

Comparison of NUMTs of Raphidocelis subcapitata, Monoraphidium neglectum, Tetradesmus obliquus, Chromochloris zofingiensis, and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Bars represent average length of NUMTs; the number of NUMTs are shown above the bars. P values (t-test) are shown.

Conserved gene repertories for lipid metabolism in the Sphaeropleales

Some Sphaeropleales species are used for the production of biomass, particularly biofuels. T. obliquus and M. neglectum accumulate palmitate (C16:0) and oleate (C18:1) as major lipid constituents, which may be suitable feedstock for biodiesel production10,34. A congener of M. neglectum, M. contortum, can also be useful for biofuel production because of its robust growth, with efficient neutral lipid accumulation, and a favourable fatty acid profile under nitrogen starvation conditions13. M. contortum and R. subcapitata mainly accumulate palmitate and oleate13,35. We searched for genes related to lipid metabolism in the Sphaeropleales, based on metabolic pathways10, and compared them to those of C. reinhardtii. They shared all the genes except for enoyl-acyl-carrier-protein reductase (EAR) (Fig. 5a). The gene for EAR in M. neglectum could not be detected by our homology search; however, Bogen et al.10 reported the presence of EAR. The Sphaeropleales possessed more genes for acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) than C. reinhardtii (Fig. 5a). DGAT catalyses the last step in triacylglycerol (TAG) biosynthesis in the acyl-CoA dependent pathway, and is composed of two families with similar structure, DGAT type1 and DGAT type2 (also known as DGTT)36. Roth et al.12 discussed the difficulties for annotation of these genes because of their high sequence diversities, and 11 reported putative genes for DGAT type1 or 2. In our analyses, although the exact number of genes for DGAT with diacylglycerol acyltransferase activity could not be confidently determined, R. subcapitata and T. obliquus tentatively possessed 11 and 12 genes for DGAT, respectively, and most of them were homologs of DGAT type2 by our phylogenetic analysis. The DGAT type2 genes of the Sphaeropleales were present in four clades (Fig. 5b), and each clade included other green algae, suggesting that the increase in genes originated in gene duplication. An increase in DGAT genes is found in other oleaginous organisms, such as Nannochloropsis species37,38. In these species, the increase in DGAT type2 genes originated in their endosymbiont via EGT37, whereas the gene number increase in the Sphaeropleales was probably caused by gene duplication in their ancestor. For the other genes related to lipid biosynthesis, the Sphaeropleales possessed a large number of genes for ACC, KAR, and KAS1/2 (Fig. 5a) as mentioned in Bogen et al.10. These findings imply that the large number of DGAT genes may be related to high lipid productivity in the Sphaeropleales.

Figure 5.

Pathways of free fatty acids and triacylglycerol in the Sphaeropleales. (a) Putative pathways and gene numbers of free fatty acids and triacylglycerol in the Sphaeropleales. The metabolic pathways were based on Bogen et al.10. Enzymes are shown in bold type. Bars represent the number of genes of Raphidocelis subcapitata (blue), Monoraphidium neglectum (red), Tetradesmus obliquus (grey), Chromochloris zofingiensis (orange), and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (cyan). (b) Unrooted ML phylogenetic tree of DGAT2. Blue-coloured operational taxonomic units represent Sphaeropleales proteins. Green-coloured clades include the Sphaeropleales. Bootstrap support (BP) is indicated above the lines where BP is more than 50%. The ML analysis was performed using IQ-tree 1.5.5 with 215 amino acids with LG + F + G4 model. Non-parametric bootstrapping was performed 100 times. ACC: acetyl-CoA carboxylase; ACP: acyl carrier protein; MAT: acyl-carrier-protein S-malonyltranferase; KAS3: beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier-protein synthase III; KAR: 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) reductase; HD: hydrolyases; EAR: enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase; KAS1/2: beta-ketoacyl-acyl-carrier-protein synthase I/II; PAH: palmitoyl-protein thioesterase; OAH: oleoyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) hydrolase; GK: glycerol kinase; GPAT: glycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase; AGPAT: 1-acetylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase; PP: phosphatidate phosphatase; DGAT: acyl-CoA:diacylglcerol acyltransferase; PDAT: phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase.

Variation in nutrient transporter genes and environmental adaptation in the Sphaeropleales

The Sphaeropleales are known generally as a dominant group in freshwater and adapted to different environmental conditions e.g.39,40. Moreover, Sphaeropleales species have high sensitivity to exogenous substances41. To characterize the adaptive potential of the Sphaeropleales to environmental variability, we compared transporter genes among the Sphaeropleales and C. reinhardtii. Most of the transporter gene repertoires for nutrients and metals were similar among the Sphaeropleales and C. reinhardtii (Supplementary Table S6); however, the Sphaeropleales possessed markedly greater numbers of genes for H+/hexose transporters (2.A.1.1, TCAD ID), amino acid permeases (2.A.18.2), peptide transporters (2.A.17.3), aquaporin (1.A.8.8), and metal-nicotianamine transporters (2.A.67.2) than C. reinhardtii (Table 2).

Table 2.

The number of genes for several transporters.

| Annotation | TCAD ID | Number of genes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. subcapitata | M. neglectum | T. obliquus | C. zofingiensis | C. reinhardtii | ||

| Aquaporin | 1.A.8.8 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 1 |

| Hexose transporter | 2.A.1.1 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 3 |

| Peptide transporter | 2.A.17.3 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Amino acid permease | 2.A.18.2 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 4 | 0 |

| Metal-nicotianamine transporter | 2.A.67.2 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0 |

The H+/hexose cotransporter is functionally related to intake of glucose from the outside of cells42,43. A trebouxiophyte, Parachlorella kessleri, also has H+/hexose cotransporter genes44. They are categorized in three classes in green algae, based on the phylogenetic relationships45. In the classes, genes in the HUP-like class are increased uniquely in mixotrophic green algae (e.g. Chlorella and Auxenochlorella), and thus the HUP-like is possibly related to the heterotrophic lifestyle45. Expression of this gene is induced during heterotrophic growth in P. kessleri. The mRNA was not detected in photosynthetically-grown cells, but immediately induced by glucose under darkness46. Interestingly, our phylogenetic analysis showed that R. subcapitata, M. neglectum, T. obliquus, and C. zofingiensis had 6, 3, 4, and 7 HUP-like genes, respectively, and they were monophyletic with heterotrophic or mixotrophic trebouxiophytes (Fig. 6a). This result suggests that the HUP-like genes of the trebouxiophytes and the Sphaeropleales had the same origin, and the genes were acquired in the common ancestor of the trebouxiophytes and the Sphaeropleales but were lacking in the Chlamydomonadales. However, it is also possible, although unlikely, that the gene has been acquired independently in the trebouxiophytes and the Sphaeropleales via horizontal gene transfer and increase in each group. Genome information of the OCC clade is needed to clearly reveal their evolutionary history. Heterotrophic growth using hexose or other simple sugars (e.g. glucose) was observed in Monoraphidium sp.47, T. obliquus48,49, and C. zofingiensis50,51. To investigate the heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth ability of R. subcapitata, we cultured it with and without 0.5% glucose under light or continuous dark conditions for 9 days (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Fig. S9). Final cell concentration was the highest in the culture treatment with glucose under light; cell concentration was ~20-fold higher in this treatment than in the treatment without glucose under light. The treatment with glucose under continuous darkness had a ~6-fold higher cell concentration than the treatment without glucose under light; cells could not grow without glucose under continuous darkness. These results suggest that R. subcapitata is mixotrophic and can grow under heterotrophic conditions without photosynthesis. The cells cultured with glucose contained many lipid bodies (Supplementary Figs S9, S10), suggesting that R. subcapitata stores excess glucose as TAG in these lipid bodies. In the case of nitrogen resources, we identified a large number of amino acid/peptide transporter genes in the Sphaeropleales, although the number of nitrate/nitrite transporter genes was not different among the Sphaeropleales and C. reinhardtii. In Chlorella vulgaris, glucose or glucose analogues induce the intake of amino acids through amino acid permeases52, even if inorganic nitrogen (i.e. ammonium or nitrate) is present in high amounts53. Based on these findings, it appears reasonable that the Sphaeropleales possess a large number of H+/hexose cotransporters and amino acid permeases. These transporters may contribute to their rapid growth under different nutrient conditions.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of H+/Hexose cotransporters and growth curves of Raphidocelis subcapitata. (a) ML tree of H+/hexose cotransporters in green algae. Inositol transporters are used as an outgroup. Orange-coloured operational taxonomic units represent proteins of the Sphaeropleales. Bootstrap support (BP) is indicated above the lines where BP is more than 50%. Bold lines represent 100% BP. The ML analysis was performed using IQ-tree 1.5.5 with 348 amino acids with LG + F + G4 model. Non-parametric bootstrapping was performed 100 times. (b) Growth curves of R. subcapitata under autotrophic and heterotrophic conditions. Blue, red, grey, and orange lines represent cultures under light without glucose, continuous dark without glucose, light with glucose, and continuous dark with glucose, respectively. The three independent cultures for each cultivated condition were counted three times. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

M. neglectum and T. obliquus can grow under highly salinity conditions (up to 1% NaCl)10,54. The adaptation to high salt stress may be conferred by the large number of genes for aquaporin (Table 2). Aquaporin can passively transport small polar molecules, such as water, across cell membranes in different species of algae55, and is likely to be used for controlling intracellular osmotic pressure. Multiple metal-nicotianamine transporters may be related to high sensitivity of the Sphaeropleales to exogenous metals. Metal-nicotianamine transporters transport various metals, such as Fe(III), Fe(II), Ni(II), Zn(II), Cu(II), Mn(II), and Cd(II) as metal-PS (phytosiderophores) or metal-NA (nicotianamine) chelates in Zea mays56,57. In Scenedesmus, organic chelators are released in inorganic medium58, and uptake of iron is regulated by siderophore secretion59. These findings suggest that the large number of genes for metal-nicotianamine transporters in R. subcapitata may induce high sensitivity to different metals. M. neglectum, T. obliquus, and C. zofingiensis also possessed multiple copies of genes for metal-nicotianamine transporters, suggesting that the Sphaeropleales might have high sensitivity to metals. In our homology search, there were few genes for metal-nicotianamine transporters among green algae, except for the Sphaeropleales; however, their origins are unknown because of their sequence diversity. The increase in transporters in the Sphaeropleales is likely to be related to their lifestyle. In the Sphaeropleales cell cycle, the stage with motility (e.g. flagellates) is not dominant or not known60,61. Immobility may force cells to adapt to different environmental conditions aided by their numerous transporters.

Conclusions

The Sphaeropleales are a dominant group of green algae and contain species important in ecosystems and those with potential for applied usage. In this study, we sequenced the nuclear, plastid, and mitochondrial genomes of R. subcapitata, and performed comparative analyses of Sphaeropleales species. The plastid and mitochondrial genomes provided insights into the phylogenetic relationships of R. subcapitata and the complex evolutionary histories in the Sphaeropleales. The nuclear genome of R. subcapitata was the more compact genome (i.e. assembly size) than those of M. neglectum, T. obliquus, and C. zofingiensis. The gene repertoire was conserved in Sphaeropleales species. Comparison of transporter genes indicated that the Sphaeropleales have the potential to adapt to different natural environmental conditions. These findings have implications for future ecological research and applications such as biomarkers and screening of highly oleaginous algae.

Methods

Culture

R. subcapitata NIES-35 (=ATCC22662) is a strain widely used in environmental bioassays e.g.60. It is an axenic strain that is available from the Microbial Culture Collection at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan (http://mcc.nies.go.jp). The strain was cultivated at 20 °C in C medium62 under white LED (~20 µmol photons/m2/s) with 12 h:12 h light:dark cycles in 300 mL glass flasks.

For tests of cultivation under mixotrophic or heterotrophic conditions, the cells were cultivated in 6 mL of C medium or C medium with 0.5% glucose in glass test tubes under the above light conditions or continuous darkness. Three separate R. subcapitata cultures were grown in each type of medium and light conditions. The cells were shaken using a TAITEC small size shaker NR-3 (TAITEC, Tokyo, Japan) at ~150 rotations per minute. The initial cell concentration was approximately 1.7 × 105 cells/mL. Cell concentrations were counted three times using a haemocytometer.

DNA and RNA extraction

For DNA extraction, R. subcapitata was cultured for 2 weeks in 500 mL of C medium. Cells were collected by gentle centrifugation and ground in a pre-cooled mortar with liquid nitrogen and 50 mg of 0.1 mm glass beads (Bertin, Rockville, MD, USA). The cells were incubated with 600 µL of CTAB extraction buffer63 at 65 °C for 1 h. DNA was separated by mixing with 500 µL of chloroform and centrifuging at 20,000 × g for 1 min; it was concentrated by standard EtOH precipitation. For RNA sequencing, cells were cultured for a week in 100 mL C medium. To acquire whole expressed genes, RNA was extracted twice just before light- and dark-phase. Cells were collected and ground as described above, and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA contamination was removed using the TURBO DNA-free Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Equal amounts of light- and dark-RNA samples were mixed and sequenced at the same time.

Sequencing

For DNA libraries, we prepared paired-end (~550 bp insert) and mate-pair (~3–4 kbp insert) libraries. The paired-end library was prepared using the TruSeq Nano DNA Library Prep Kit for NeoPrep (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with the NeoPrep system (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The mate-pair library was prepared using the Nextera Mate Pair Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s protocol. We also prepared a paired-end RNA library (~550 bp insert) using the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). mRNA was purified using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England BioLabs). All libraries were sequenced on the MiSeq sequencing system (Illumina) using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3, 600 cycles (300 bp × 2), and the MiSeq Reagent Kit v2, 150 cycles (75 bp × 2), for the paired-end and mate-pair libraries, respectively.

Assembly and annotation

We acquired 3,847,746, 16,768,250, and 1,394,371 read pairs for DNA paired-end, mate-pair, and RNA paired-end libraries, respectively. The reads were deposited in DDBJ/Genbank/ENA with accession numbers DRR090198 (DNA paired-end), DRR090199 (DNA mate-pair), and DRR090200 (RNA paired-end). The sequences were trimmed using Trimmomatic 0.3664 with default options. The DNA paired-end reads were used for in silico genome size estimation by Jellyfish 2.2.665 with the 17-mer option. The genome was assembled using SPAdes Genome Assembler 3.9.066 with default options. Scaffolding was performed using SSPACE-standard 3.067, and some gaps were closed by GapFiller v1.1068. To extract plastid and mitochondrial sequences, we performed a blastx69 search using available plastid and mitochondrial proteins of the Sphaeropleales as a query. The plastid and mitochondrial genomes were automatically annotated using Prokka v1.1170, and manually curated on an Artemis genome browser71. rRNA and tRNA were also searched using RNAmmer 1.272 and tRNAscan-SE 2.073, respectively. Group I and II introns were initially detected using RNAweasel74, and curated by alignments with homologs. Tandem repeats were found using Tandem Repeats Finder 4.0975. Gene models of the nuclear scaffolds were constructed following the funannotate pipeline 0.3.7 (https://github.com/nextgenusfs/funannotate). To acquire evidence for gene model construction, we mapped RNA-seq reads to the scaffolds using HISAT2 2.0.476, and constructed transcript-based gene models using Trinity 2.2.077 and PASA pipeline 2.0.278. For the nuclear genome of T. obliquus, because annotation was not available, we annotated the scaffolds (accession number GCA_900108755.1). Repeat regions of the scaffolds were soft-masked using RepeatModeler and RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org). Gene models were predicted using AUGUSTUS79, for which training was performed using BUSCO28 with the eukaryote dataset. The nuclear, plastid, and mitochondrial genomes of R. subcapitata were deposited in DDBJ/Genbank/ENA with accession numbers BDRX01000001–BDRX01000300, AP018038, and AP018037, respectively.

Phylogenetic analyses

To infer the phylogenetic relationships between R. subcapitata and other species of the Sphaeropleales, we performed phylogenetic analyses using plastid and mitochondrial genome-encoded proteins. For plastid proteins, we used 55 proteins in the dataset described by Fučíková et al.20 (AtpA, AptB, AtpE, AtpF, AtpH, AtpI, CcsA, CemA, ClpP, PetB, PetD, PetG, PetL, PsaA, PsaB, PsaC, PsaJ, PsbA, PsbB, PsbC, PsbD, PsbE, PsbF, PsbI, PsbJ, PsbK, PsbL, PsbM, PsbN, PsbT, PsbZ, RbcL, Rpl2, Rpl5, Rpl14, Rpl16, Rpl20, Rpl23, Rpl36, RpoA, RpoBa, RpoBb, RpoC2, Rps3, Rps4, Rps7, Rps8, Rps9, Rps11, Rps12, Rps14, Rps18, Rps19, TufA, and Ycf3). The dataset was composed of 12 organisms in the Sphaeropleales. The complete plastid genome of Ourococcus multisporus was unavailable, but instead, we used its protein sequences. Mychonastes homosphaera was excluded from the dataset because of its rapid evolutionary rate. D. salina and C. reinhardtii were used as an outgroup. For the mitochondrial dataset, we used all mitochondrial genome encoding proteins: Atp6, Atp9, Cob, Cox1, Cox2a, Cox3, Nad1, Nad2, Nad3, Nad4, Nad4L, Nad5, and Nad6. The dataset was composed of 17 organisms. Stigeoclonium helveticum (Chaetophorales) was used as an outgroup. Both sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.22180, and highly divergent regions were manually trimmed with MEGA 6.0.681. Substitution models were tested using IQ-TREE 1.4.482. Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed using RAxML 8.2.983 with the LG + GAMMA + F + I model. Non-parametric bootstrap analyses were replicated 200 times. Bayesian analyses were performed using MrBayes v3.2.684 with the same substitution model. The inference consisted of 1,000,000 generations with sampling every 1,000 generations using four Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMCMC) simulations. Two separate runs were performed, and Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated from the majority rule consensus of the tree sampled after the initial 250 burn-in trees.

Identification of gene families, NUMTs, and genes for lipid biosynthesis and transporters

Gene families were searched using TreeFam 929 with an e-value cut-off of <1E−5. NUMTs were searched by blastn with the mitochondrial genomes as a query, with an e-value cut-off of <1E−3. Genes for lipid biosynthesis were based on Bogen et al.10, and searched using blastp with the proteins of Arabidopsis thaliana as a query, with an e-value cut-off of <1E−10. Transporters were identified using blastp with the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB)85 as a query, with an e-value cut-off of <1E−5.

Data availability

The strain used in this study (R. subcapitata, NIES-35) is available from the Microbial Culture Collection at the National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) (http://mcc.nies.go.jp), Japan. The DNA paired-end, mate-pair, and RNA paired-end reads were deposited in DDBJ/Genbank/ENA with accession numbers DRR090198, DRR090199, and DRR090200, respectively. The nuclear, plastid, and mitochondrial genomes were deposited in DDBJ/Genbank/ENA with accession numbers BDRX01000001–BDRX01000300, AP018038, and AP018037, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the National BioResource Project for Algae (http://www.nbrp.jp) under grant number 17km0210116j0001, which is funded by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Author Contributions

S.S., H.Y., and M.K. designed this study. S.S. assembled the genomes, performed comparative analyses, and wrote the manuscript. S.S. and N.N. generated sequence data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-26331-6.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Leliaert F, et al. Phylogeny and molecular evolution of the green algae. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2012;31:1–46. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2011.615705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falkowski PG, et al. The evolution of modern eukaryotic phytoplankton. Science. 2004;305:354–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1095964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf M, Buchheim M, Hegewald E, Krienitz L, Hepperle D. Phylogenetic position of the Sphaeropleaceae (Chlorophyta) Plant Syst. Evol. 2002;230:161–171. doi: 10.1007/s006060200002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krienitz L, Bock C, Nozaki H, Wolf M. SSU rRNA gene phylogeny of morphospecies affiliated to the bioassay alga ‘Selenastrum capricornutum’ recovered the polyphyletic origin of crescent-shaped Chlorophyta. J. Phycol. 2011;47:880–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merchant SS, et al. The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science. 2007;318:245–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1143609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanschen ER, et al. The Gonium pectorale genome demonstrates co-option of cell cycle regulation during the evolution of multicellularity. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11370. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prochnik SE, et al. Genomic analysis of organismal complexity in the multicellular green alga Volvox carteri. Science. 2010;329:223–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1188800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirooka S, et al. Acidophilic green algal genome provides insights into adaptation to an acidic environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:E8304–E8313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707072114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferris P, et al. Evolution of an expanded sex-determining locus in Volvox. Science. 2010;328:351–354. doi: 10.1126/science.1186222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogen C, et al. Reconstruction of the lipid metabolism for the microalga Monoraphidium neglectum from its genome sequence reveals characteristics suitable for biofuel production. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:926. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carreres BM, et al. Draft genome sequence of the oleaginous green alga Tetradesmus obliquus UTEX 393. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e01449–16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01449-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth MS, et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and transcriptome of the green alga Chromochloris zofingiensis illuminates astaxanthin production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:E4296–E4305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619928114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogen C, et al. Identification of Monoraphidium contortum as a promising species for liquid biofuel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013;133:622–626. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.01.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi-Ishimaru Y, Ohama T, Kawatsu Y, Nakamura K, Osawa S. UAG is a sense codon in several chlorophycean mitochondria. Curr. Genet. 1996;30:29–33. doi: 10.1007/s002940050096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nedelcu AM, Lee RW, Lemieux C, Gray MW, Burger G. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of Scenedesmus obliquus reflects an intermediate stage in the evolution of the green algal mitochondrial genome. Genome Res. 2000;10:819–831. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.6.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez-Martínez X, et al. Subunit II of cytochrome c oxidase in chlamydomonad algae is a heterodimer encoded by two independent nuclear genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11302–11309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodríguez-Salinas E, et al. Lineage-specific fragmentation and nuclear relocation of the mitochondrial cox2 gene in chlorophycean green algae (Chlorophyta) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2012;64:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funes S, et al. A green algal apicoplast ancestor. Science. 2002;298:2155. doi: 10.1126/science.1076003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fučíková K, Lewis PO, González-Halphen D, Lewis LA. Gene arrangement convergence, diverse intron content, and genetic code modifications in mitochondrial genomes of Sphaeropleales (Chlorophyta) Genome Biol. Evol. 2014;6:2170–80. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fučíková K, Lewis PO, Lewis LA. Chloroplast phylogenomic data from the green algal order Sphaeropleales (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) reveal complex patterns of sequence evolution. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016;98:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawley MW, Dean ML, Dimmer SK, Fawley KP. Evaluating the morphospecies concept in the Selenastraceae (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) J. Phycol. 2005;42:142–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00169.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemieux C, Vincent AT, Labarre A, Otis C, Turmel M. Chloroplast phylogenomic analysis of chlorophyte green algae identifies a novel lineage sister to the Sphaeropleales (Chlorophyceae) BMC Evol. Biol. 2015;15:264. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0544-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farwagi AA, Fučíková K, McManus HA. Phylogenetic patterns of gene rearrangements in four mitochondrial genomes from the green algal family Hydrodictyaceae (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyceae) BMC Genomics. 2015;16:826. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2056-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee H-G, et al. Unique mitochondrial genome structure of the green algal strain YC001 (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyta), with morphological observations. Phycologia. 2016;55:72–78. doi: 10.2216/15-71.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kück U, Jekosch K, Holzamer P. DNA sequence analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of the green alga Scenedesmus obliquus: evidence for UAG being a leucine and UCA being a non-sense codon. Gene. 2000;253:13–18. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Cambiaire J-C, Otis C, Lemieux C, Turmel M. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the chlorophycean green alga Scenedesmus obliquus reveals a compact gene organization and a biased distribution of genes on the two DNA strands. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006;6:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna N. T. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruan J, et al. TreeFam: 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D735–740. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D109–114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wibberg D, et al. Establishment and interpretation of the genome sequence of the phytopathogenic fungus Rhizoctonia solani AG1-IB isolate 7/3/14. J. Biotechnol. 2013;167:142–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sumner AT, de la Torre J, Stuppia L. The distribution of genes on chromosomes: A cytological approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1993;37:117–122. doi: 10.1007/BF02407346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pozzoli U, et al. Both selective and neutral processes drive GC content evolution in the human genome. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandal S, Mallick N. Microalga Scenedesmus obliquus as a potential source for biodiesel production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;84:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nascimento IA, et al. Screening microalgae strains for biodiesel production: lipid productivity and estimation of fuel quality based on fatty acids profiles as selective criteria. BioEnergy Res. 2013;6:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12155-012-9222-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turchetto-Zolet AC, et al. Evolutionary view of acyl-CoA diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT), a key enzyme in neutral lipid biosynthesis. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011;11:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang D, et al. Nannochloropsis genomes reveal evolution of microalgal oleaginous traits. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radakovits R, et al. Draft genome sequence and genetic transformation of the oleaginous alga Nannochloropis gaditana. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:686. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldisserotto C, et al. Salinity promotes growth of freshwater Neochloris oleoabundans UTEX 1185 (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyta): morphophysiological aspects. Phycologia. 2012;51:700–710. doi: 10.2216/11-099.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fawley MW, Fawley KP, Buchheim MA. Molecular diversity among communities of freshwater microchlorophytes. Microb. Ecol. 2004;48:489–499. doi: 10.1007/s00248-004-0214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagai T, Taya K, Yoda I. Comparative toxicity of 20 herbicides to 5 periphytic algae and the relationship with mode of action. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016;35:368–375. doi: 10.1002/etc.3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams LE, Lemoine R, Sauer N. Sugar transporters in higher plants – a diversity of roles and complex regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:283–290. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01681-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozcan S, Johnston M. Function and regulation of yeast hexose transporters. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:554–69. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.554-569.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauer N, Tanner W. The hexose carrier from. Chlorella. FEBS Lett. 1989;259:43–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao C, et al. Oil accumulation mechanisms of the oleaginous microalga Chlorella protothecoides revealed through its genome, transcriptomes, and proteomes. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:582. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hilgarth C, Sauer N, Tanner W. Glucose increases the expression of the ATP/ADP translocator and the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase genes in Chlorella. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:24044–24047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu X, et al. Isolation of a novel strain of Monoraphidium sp. and characterization of its potential application as biodiesel feedstock. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;121:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camacho Rubio F, Martínez Sancho ME, Sánchez Villasclaras S, Delgado Pérez A. Influence of pH on the kinetic and yield parameters of Scenedesmus obliquus heterotrophic growth. Process Biochem. 1989;40:133–136. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abeliovich A, Weisman D. Role of heterotrophic nutrition in growth of the alga Scenedesmus obliquus in high-rate oxidation ponds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1978;35:32–37. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.1.32-37.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun N, Wang Y, Li Y-T, Huang J-C, Chen F. Sugar-based growth, astaxanthin accumulation and carotenogenic transcription of heterotrophic Chlorella zofingiensis (Chlorophyta) Process Biochem. 2008;43:1288–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2008.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J, et al. Differential lipid and fatty acid profiles of photoautotrophic and heterotrophic Chlorella zofingiensis: Assessment of algal oils for biodiesel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cho BH, Sauer N, Komor E, Tanner W. Glucose induces two amino acid transport systems in Chlorella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1981;78:3591–3594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sauer N, Komor E, Tanner W. Regulation and characterization of two inducible amino-acid transport systems in Chlorella vulgaris. Planta. 1983;159:404–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00392075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gan X, Shen G, Xin B, Li M. Simultaneous biological desalination and lipid production by Scenedesmus obliquus cultured with brackish water. Desalination. 2016;400:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2016.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderberg HI, Danielson JÅ, Johanson U. Algal MIPs, high diversity and conserved motifs. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011;11:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schaaf G, et al. ZmYS1 functions as a proton-coupled symporter for phytosiderophore- and nicotianamine-chelated metals. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9091–9096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murata Y, et al. A specific transporter for iron(III)-phytosiderophore in barley roots. Plant J. 2006;46:563–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benderliev KM, Ivanova NI. Determination of available iron in mixtures of organic chelators secreted by Scenedesmus incrassatulus. Biotechnol. Tech. 1996;10:513–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00159516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benderliev KM, Ivanova NI. High-affinity siderophore-mediated iron-transport system in the green alga Scenedesmus incrassatulus. Planta. 1994;193:163–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00192525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamagishi T, Yamaguchi H, Suzuki S, Horie Y, Tatarazako N. Cell reproductive patterns in the green alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata (=Selenastrum capricornutum) and their variations under exposure to the typical toxicants potassium dichromate and 3,5-DCP. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trainor FP, Burg CA. Scenedesmus obliquus sexuality. Science. 1965;148:1094–1095. doi: 10.1126/science.148.3673.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ichimura, T. Sexual cell division and conjugation-papilla formation in sexual reproduction of Closterium strigosum. In International Symposium on Seaweed Research, 7th, Sapporo 208–214 (University of Tokyo Press, 1971).

- 63.Lang BF, Burger G. Purification of mitochondrial and plastid DNA. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:652–660. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marçais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:764–70. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:578–579. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boetzer M, Pirovano W. Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R56. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rutherford K, et al. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lagesen K, et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schattner P, Brooks AN, Lowe TM. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W686–689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lang BF, Laforest M-J, Burger G. Mitochondrial introns: a critical view. Trends Genet. 2007;23:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haas BJ, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haas BJ, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stanke M, Schöffmann O, Morgenstern B, Waack S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Katoh K, Toh H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief. Bioinform. 2008;9:286–98. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ronquist F, et al. Mrbayes 3.2: Efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saier MH, et al. The Transporter Classification Database (TCDB): recent advances. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D372–D379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The strain used in this study (R. subcapitata, NIES-35) is available from the Microbial Culture Collection at the National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) (http://mcc.nies.go.jp), Japan. The DNA paired-end, mate-pair, and RNA paired-end reads were deposited in DDBJ/Genbank/ENA with accession numbers DRR090198, DRR090199, and DRR090200, respectively. The nuclear, plastid, and mitochondrial genomes were deposited in DDBJ/Genbank/ENA with accession numbers BDRX01000001–BDRX01000300, AP018038, and AP018037, respectively.