Abstract

Although rare, canal of Nuck hernias containing pelvic structures or peritoneal contents are an important differential consideration in the pediatric setting of a palpable labial mass. This diagnosis should be considered early as there is a high rate of associated ovarian torsion in the setting of incarcerated hernias containing ovaries. Early sonographic evaluation is crucial to establish the diagnosis. We report an extremely rare case of a 2-month-old who presented with right labial swelling due to a canal of Nuck hernia containing the uterus, the ipsilateral ovary, and the fallopian tube.

Keywords: Canal Nuck, Labial mass, Uterus, Ovary

Case report

A 2-month-old female infant presented to the emergency department with a palpable, nontender, right labial mass. One day earlier, the infant had been seen by her primary physician, who palpated a right labial firmness and referred her for evaluation by a specialist. The infant's guardians first noticed this mass approximately 1 week before and reported no other symptoms such as fussiness, fever, or tenderness to touch. The patient was born as a full-term infant without perinatal complications. The infant had never been hospitalized and had no other significant medical or surgical history.

A focused ultrasound examination was performed, which demonstrated a right inguinal hernia extending into the right labia containing the uterus, the right ovary, and the fallopian tube. The contralateral left ovary was pulled over to the right side of the pelvis but remained above the right inguinal canal. (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

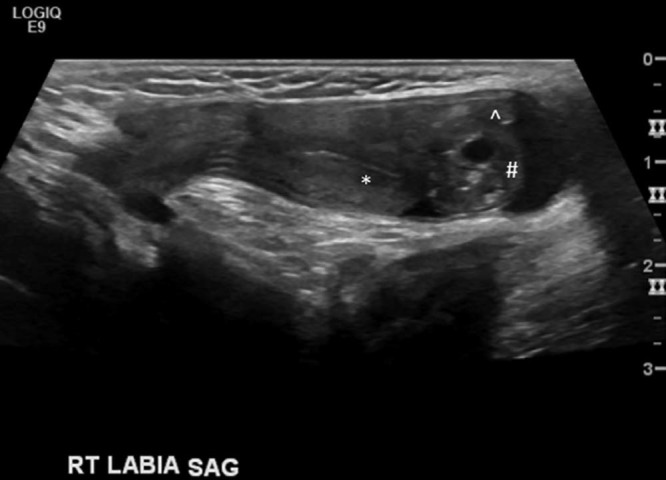

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound image demonstrating a sagittal view of the right inguinal region shows the canal of Nuck hernia containing the uterus (*), the RT ovary (#), and the fallopian tube (^).

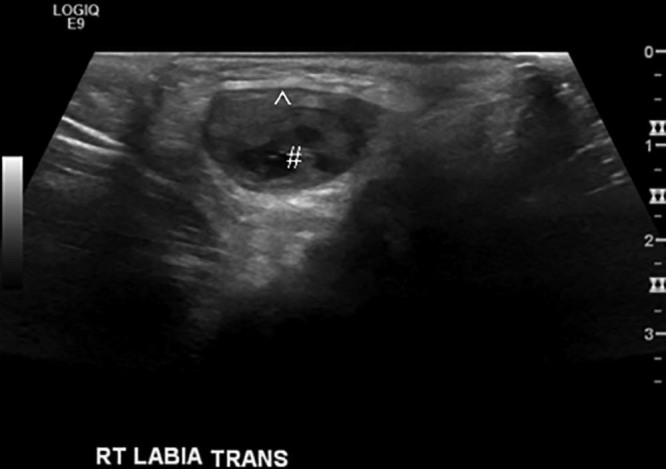

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound image with TRANS view of the RT labial region shows a herniated RT ovary (#) and fallopian tube (^). RT, right; TRANS, transverse.

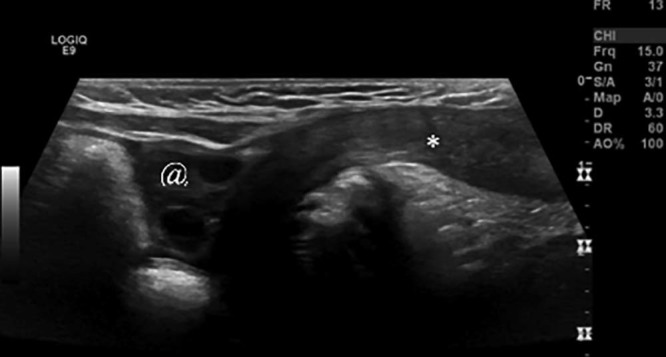

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound image with sagittal view of the right inguinal region shows the right canal of Nuck hernia containing the uterus (*) with the left ovary (@) pulled over to the right side of the pelvis but remaining above the inguinal ring.

On physical examination, this right inguinal hernia and contents were easily reducible without evidence of incarceration. There was no associated tenderness or erythema. An elective hernia repair surgery was planned. At the time of surgery, a sliding right inguinal hernia was seen, which contained the entire uterus, the right ovary, and right fallopian tube. The left ovary wall pulled over to the right side of the pelvis but remained intraperitoneal. Reduction and hernia repair was performed without complication (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). There was no evidence of ovarian torsion or a contralateral inguinal hernia at the time of surgery.

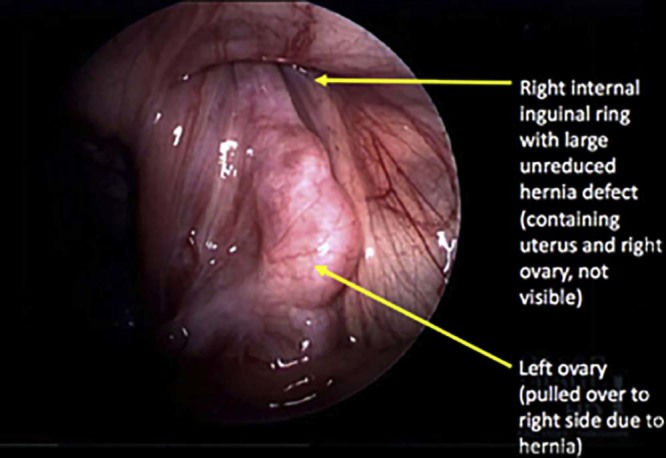

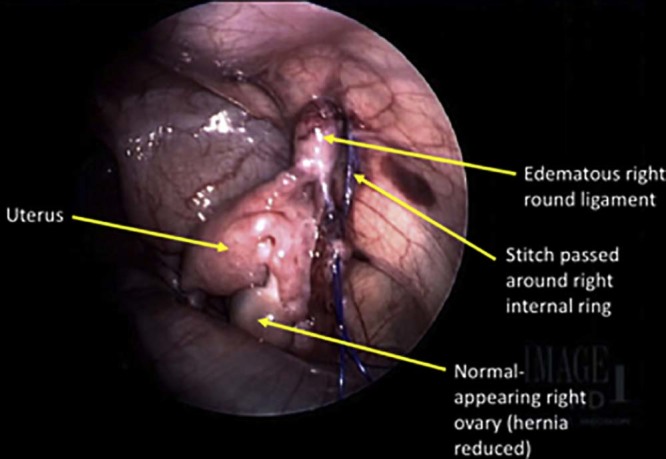

Fig. 4.

Initial intraoperative image during laparoscopic surgery demonstrates the left ovary pulled over to the right side of the pelvis because of the right inguinal hernia, whose contents are not visible from this peritoneal approach.

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative image obtained after manual hernia reduction shows the uterus, the right ovary, and the right fallopian tube, which have been returned to the pelvis, and the edematous right round ligament is noted extending into the internal ring. A stitch has been passed around the medial and the lateral aspects of the internal ring for repair of the hernia.

Discussion

Pediatric inguinal hernias occur most commonly in infancy and in early childhood, with the reported incidence ranging between 0.8% and 4.4% [1], [2]. The inguinal hernias in infancy are indirect inguinal hernias [1], [2]. Indirect inguinal hernias occur when abdominal contents protrude through the deep inguinal ring, lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels due to a patent inguinal canal from failure of closure of the embryonic processus vaginalis [3]. In contrast, direct inguinal hernias tend to occur in the middle aged and the elderly, when abdominal contents herniate medial to the inferior epigastric vessels through a weak spot in the fascia of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal [3]. In girls, a patent inguinal canal is called a canal of Nuck.

The prenatal development of the inguinal canal is due to the contribution of 2 main fetal anatomic structures, the processus vaginalis and the gubernaculum testis [2]. The gubernaculum testis attaches to the lower pole of the fetal gonad along its superior aspect and attaches to the skin of the fetal groin along its inferior aspect. In male infants, the gubernaculum testis assists in descent of testis from abdomen through the inguinal canal into the scrotum. In female infants, the midpoint of the gubernaculum testis attaches to the uterus and prevents ovarian descent into the inguinal canal [3]. The ovarian ligament, which extends medially from the ovary to the uterus, and the round ligament, which extends into the inguinal canal, are postnatal homologues of the fetal gubernaculum testis in female infants [3].

The processus vaginalis is a tubular fold of peritoneum that invaginates into the inguinal canal. The processus vaginalis develops around the sixth month of gestation and, in female infants, obliterates around the eighth month of gestation. The obliteration of the processus vaginalis proceeds gradually in a superior-to-inferior direction [2]. If the processus vaginalis remains patent, it is termed the canal of Nuck. The canal of Nuck allows pelvic contents, such as bowel, omental fat, fluid, ovary, fallopian tube, rarely the uterus, and the urinary bladder, to herniate through the inguinal canal to the labia majora.

Inguinal hernias occur more commonly among premature infants with reports that as many as 30% of premature infants develop inguinal hernias [1], [2]. Also, indirect inguinal hernias are 6 times more common in boys than in girls [1], [2]. Canal of Nuck hernias containing ovaries with or without fallopian tubes is reported in 15%-20% of all canal of Nuck hernias in infancy. However, hernias containing the uterus are extremely rare [1], [2], [4]. The pathology behind uterine hernias into the canal of Nuck is controversial, but an anatomic abnormality involving the uterine and ovarian suspensory ligaments is suspected [2], [4].

There is a higher incidence of canal of Nuck hernias containing ovary, testis, or uterine parts in certain syndromes of sexual development, such as androgen insensitivity syndrome and Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. With these syndromes, there is a high risk of incarceration or torsion of these inguinal gonads and uterine parts [5]. Accessory ovaries (connected by ligaments to a normal ovary) have also been reported to herniate along with the normal ovary into the canal of Nuck hernia [5].

The differential diagnosis of an asymptomatic palpable mass in the inguinal region of a female child includes lymphadenopathy, canal of Nuck hernia, hydrocele of the canal of Nuck, femoral hernia, Bartholin gland cyst, and benign masses such as lipoma. Ultrasound is the preferred modality in the evaluation of inguinal masses as this technique depicts the contents well and expedites surgical planning [6]. Early diagnosis of a canal of Nuck hernia containing the ovary is necessary as there is a risk for ovarian torsion without operative intervention. The risk for ovarian torsion is increased if there is an associated incarceration, which occurs in 43% of hernias containing ovaries [5]. Incarceration is felt to increase the risk of ovarian torsion due to blockage of normal venous and lymphatic return from the ovary contained in the canal of Nuck [5]. Ultrasound can establish a definite diagnosis in 100% of cases of canal of Nuck abnormalities [7], [8].

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.George E.K., Oudesluys-Murphy A.M., Madern G.C., Cleyndert P, Blomjous J.G.A.M. Inguinal hernias containing the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovary in premature female infants. J Pediatr. 1999;136:696–697. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.105140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deinkuyu B.E., Affrancheh M.R., Sonmez D., Koloğlu M.B., Fitoz S. Canal of Nuck in a female infant containing uterus, bilateral adnexa and bowel. Balkan Med J. 2016;33:566–568. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2016.150643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shadbolt C.L., Heinze S.B., Dietrich R.B. Imaging of groin masses: inguinal anatomy and pathologic conditions revisited. Radiographics. 2001;21:261–271. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.suppl_1.g01oc17s261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ming Y.C., Luo C.C., Chao H.C., Chu S.M. Inguinal hernia containing uterus and uterine adnexa in female infants: report of two cases. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011;52:103–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi K.H., Baek H.J. Incarcerated ovarian herniation of the canal of Nuck in a female infant: ultrasonographic findings and review of literature. Ann Med Surg. 2016;9:38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heller D.S. Lesions of the round ligament and canal of Nuck—it is not always an inguinal hernia: a review. J Gynec Surg. 2015;31:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang D., Kim H., Kim S., Lim S., Park S., Lim J. Ultasonographic diagnosis of ovary-containing hernias of the canal of Nuck. Ultrasonography. 2014;33(3):178–183. doi: 10.14366/usg.14010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akkoyun U., Kucukomanoglu I., Yalinkilinc E. Cyst of the canal of Nuck in pediatric patients. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:353–356. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.114166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]