Abstract

A persistent change in illumination causes light-adaptive changes in retinal neurons. Light adaptation improves visual encoding by preventing saturation and by adjusting spatiotemporal integration to increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and utilize signaling bandwidth efficiently. In dim light, the visual input contains a greater relative amount of quantal noise, and vertebrate receptive fields are extended in space and time to increase SNR. Whereas in bright light, SNR of the visual input is high, the rate of synaptic vesicle release from the photoreceptors is low so that quantal noise in synaptic output may limit SNR postsynaptically. Whether and how reduced synaptic SNR impacts spatiotemporal integration in postsynaptic neurons remains unclear. To address this, we measured spatiotemporal integration in retinal horizontal cells and ganglion cells in the guinea pig retina across a broad illumination range, from low to high photopic levels. In both cell types, the extent of spatial and temporal integration changed according to an inverted U-shaped function consistent with adaptation to low SNR at both low and high light levels. We show how a simple mechanistic model with interacting, opponent filters can generate the observed changes in ganglion cell spatiotemporal receptive fields across light-adaptive states and postulate that retinal neurons postsynaptic to the cones in bright light adopt low-pass spatiotemporal response characteristics to improve visual encoding under conditions of low synaptic SNR.

Keywords: horizontal cell, light adaptation, retina, retinal ganglion cell, white noise analysis

INTRODUCTION

Adaptive mechanisms in the sensory nervous system improve information transmission under changing stimulus conditions. For example, adaptation prevents response saturation by adjusting response gain and helps encode sensory input efficiently by giving priority to those aspects that carry the most information (Atick 2011; van Hateren 1992a). Efficient encoding depends directly on signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the sensory and synaptic input, and several strategies for optimal encoding have been described in theory (Atick and Redlich 1990; Shannon and Weaver 1949; van Hateren 1992b). In vision, in dim light, biological sources of noise such as voltage-gated channels, photon shot noise, and stochastic variations in synaptic vesicle release cause SNR of the visual signal within the retina to be low. Under these conditions, information is best encoded with a low-pass frequency-response characteristic (filter) to preserve lower frequencies through increased integration and avoid frequencies outside of the photoreceptor response range. With increasing light, SNR increases and optimal encoding becomes increasingly band pass to selectively attenuate low frequencies and commit signaling capacity to high frequencies. This is useful because low frequencies are more redundant compared with high frequencies, and high frequencies can carry more information per unit of time (Srinivasan et al. 1982; van Hateren 1992b).

Many lines of evidence show that light-adaptive changes in the visual systems of both vertebrates and invertebrates adhere to these principles (Atick 2011; Sterling and Laughlin 2015; van Hateren 1992a). Invertebrate photoreceptor cells depolarize to light so that SNR of synaptic vesicle release increases monotonically with light level. In the fly (Calliphora), increasing illumination shifts spatiotemporal encoding in visual neurons at the level of the lamina (large monopolar cells) from low pass to band pass (van Hateren 1992a). Several studies have shown that in the visual system of vertebrates, including cat and primate, increasing light level changes the response characteristics of retinal ganglion cells and their synaptic targets in the lateral geniculate nucleus from low pass to band pass (Benardete and Kaplan 1997; Enroth-Cugell and Shapley 1973; Frishman et al. 1987; Purpura et al. 1990). Separate experiments showed that in the same cells, contrast sensitivity, a direct measure of SNR, also increases monotonically with light level (Derrington and Lennie 1982; Enroth-Cugell and Shapley 1973). Thus light-adaptive changes in mammals appear consistent with first principles of efficient information transfer. However, vertebrate photoreceptors hyperpolarize to light: increasing background illumination level reduces the tonic rate of rod and cone synaptic vesicle release (Choi et al. 2005). This particular physiology implies that at high light levels, stochastic fluctuations in synaptic release should be large relative to the mean release rate so that SNR of the transmitted signal would be reduced. Few studies, however, have explored adaptation at light levels where synaptic SNR might become limiting, and how potentially increased synaptic noise of the cone output signal at high light levels might impact downstream signaling remains unclear.

Direct recordings of light-evoked responses in mammalian retinal neurons at light levels exceeding those of most previous studies demonstrated a decrease in SNR, measured as the contrast detection threshold (Borghuis et al. 2009). In both horizontal cells and ganglion cells, SNR of the visually evoked response peaked in the mid-photopic light level (~104 R*·cone−1·s−1) and decreased at both lower and higher light levels. Control experiments (see methods) show that this decrease does not likely reflect a shortcoming of the in vitro preparation, such as irreversible bleaching of the cone photopigment. We propose that these data reflect reduced signal quality at high light levels (>105 R*·cone−1·s−1) and ask whether light-adaptive mechanisms act to minimize the impact of this apparent reduction. If, as in the fly, visual neurons in the mammalian retina adapt in accordance with optimal signaling theory, then this predicts band-pass filter characteristics at a mid-photopic light level but increasingly low-pass filter characteristics at both lower and higher intensities to deemphasize high frequencies more corrupted by photon and synaptic noise, respectively. To test this, we measured spatiotemporal response characteristics at two synaptic stages in the guinea pig retina: directly postsynaptic to the cones (horizontal cells) and at the level of the retinal output (ganglion cells). Recording from whole mount tissues with attached retinal pigment epithelium and sclera permitted measurements over a large range of light levels with intact rod and cone visual sensitivity.

Increasing illumination changed horizontal cell and ganglion cell responses from low pass to band pass, consistent with previous reports, but these changes reversed at light levels above ~104 R*·cone−1·s−1, in line with our predictions. Changes in the filter characteristic were more pronounced in ganglion cells compared with horizontal cells. In addition, horizontal cell and ganglion response amplitudes, too, showed an inverted U-shape dependence on light level, with a peak in the mid-photopic light levels. Because temporal integration times decreased monotonically with light level up to the highest light level tested, the reversal of filter characteristics above mid-photopic light levels was not caused by a loss of photosensitivity. We conclude that the observed reversal to low-pass responses in bright light is a functional adaptation that helps maintain signal quality when SNR of the cone synaptic output is reduced.

METHODS

Data were obtained from whole mount guinea pig retinas with sclera attached and recorded at physiological temperature (36°C) in vitro. All procedures were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines under protocols approved by the University of Pennsylvania Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals of either sex were deeply anesthetized (40 mg/kg ketamine, 5 mg/kg xylazine plus 50 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital) and the eyes removed and placed in oxygenated (95% O2–5% CO2) Ames medium (Sigma-Aldrich) with glucose (3.6 g/l; pH 7.4). Each eye was hemisected, and the anterior half and lens were removed. The posterior half was radially incised and mounted on a cellulose filter membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) with the ganglion cell layer up, preserving attachment of the retina to pigment epithelium, choroid, and sclera. The retina preparation was placed in a recording chamber on an upright microscope (Olympus BX51) and continuously perfused with Ames medium at ~6 ml/min.

Horizontal cell recordings.

We recorded from horizontal cells intracellularly using glass electrodes (70–200 MΩ) advanced through the retina from the ganglion cell side without visual guidance. The electrode signal was amplified (Neurodata IR-283; Cygnus Technologies, Delaware Water Gap, PA) and digitized at 2 kHz using a data acquisition board (PCI 1200; National Instruments, Austin, TX), Apple Macintosh G4 computer, and custom software (StimDemo) written in C language (Metroworks Codewarrior; Freeware Semiconductors, Austin, TX).

Electrodes were backfilled with 1.5 M K-acetate solution containing 5% neurobiotin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and a fluorescent dye (Alexa Fluor 488 or 568; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for identification of cell type before recording. After recording, neurobiotin was injected into the cell with current pulses through the electrode (±1 nA, 1 Hz; 1 min). Tissue was then fixed (4% paraformaldehyde; 20 min at room temperature) and neurobiotin cross-reacted with fluorophore-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Horizontal cell type (A or B; Peichl and González-Soriano 1994) was determined from the dendritic morphology obtained with a confocal laser scanning microscope (×40 objective, N.A. 1.3). A-type horizontal cells were encountered most frequently and could be recorded more stably than B-type horizontal cells. For this reason, and because they exclusively contact the cone photoreceptors, which mediate vision under photopic conditions, we report results only for A-type horizontal cells.

Ganglion cell recordings.

We recorded from ON- and OFF-type brisk-transient ganglion cells (alpha cells). A ganglion cell was selected for recording on the basis of soma size (15–20 µm) and soma morphology (ON: angular, stellate; OFF: smooth, egg shaped) using infrared illumination and a charge-coupled device camera (model RS-170; Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). Extracellular spikes were recorded with glass electrodes filled with Ames medium in loose-patch configuration (electrode impedance 8–12 MΩ; Flaming/Brown P-97 pipette puller; Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA). The electrode signal was conventionally amplified and filtered (Neurodata IR-283; Cygnus Technologies), spikes were detected in hardware (custom-built analog window discriminator), and their time of occurrence was recorded at 0.5-ms resolution. Cell type was confirmed from light-evoked responses using established criteria (Borghuis et al. 2008, 2009): a transient response to light increments and decrements for ON- and OFF-type cells, respectively; peaks at ~3 ms in the response autocorrelogram; and a biphasic temporal filter (Benardete and Kaplan 1997; Chander and Chichilnisky 2001; Purpura et al. 1990), based on the recorded response at 5.0 × 103 R*·cone−1·s−1.

After recording, recorded cells were penetrated with a sharp glass electrode (70–200 MΩ) and electrophoresed with a mixture of fluorescent dye (Alexa Fluor 488 or 568) and neurobiotin (±1-nA square-wave current pulses through the electrode, 1-Hz duty cycle; 1 min). Images of cellular morphology were obtained with a confocal microscope to confirm cell type, as described for horizontal cells.

Visual stimulation.

The whole mount retina was stimulated with a miniature cathode ray tube (CRT) display (Lucivid; MicroBrightField, Colchester, VT; 60-Hz frame rate with P43 phosphor and peak emission at 543 nm) projected through the microscope objective lens (×4, N.A. 0.10). Display image size on the retina was 3.2 × 2.4 mm; the surrounding retina was not illuminated (mean luminance <101 photons·mm−2·s−1). Stimulus light level (mean luminance) was varied over 3.5 log units via a computer-controlled radial neutral density filter. Mean luminance ranged from low-mesopic to high-photopic light levels (4 × 101 to 2.5 × 105 photons·mm−2·s−1, equivalent to 7.2 × 101 to 3.6 × 104 R*·cone−1·s−1 and 9.5 × 101 to 4.7 × 104 R*·rod−1·s−1). Light levels were checked regularly (IL1400; International Light Technologies, Peabody, MA) and maintained constant between experiments.

Before recording, the retina was adapted to the lowest light level for 30–45 min. To minimize adaptation artifacts, spatiotemporal filters were measured at increasing light levels, increased in 0.5 log10-unit steps. Duration of the recording at each light level was ~3 min; the change in light level was near instantaneous (switch time <100 ms from one level to the next) and occurred under spatially uniform illumination. Recordings started ~10 s after each change in light level. Cells were stimulated with random binary luminance sequences presented either full-field (spatially uniform) or as a circular spatial pattern centered on the soma, comprising 48 concentric annuli of increasing diameter (see Fig. 4A). Each annulus was 25 µm wide; the outer diameter of the largest annulus was 2,400 µm to capture potentially large inhibitory surrounds at low light levels. Luminance of each annulus was updated every 33 ms according to a random binary sequence. For both full-field and spatial stimulation, contrast was 70%, i.e., luminance was either 70% greater or 70% smaller than the mean (Michelson contrast).

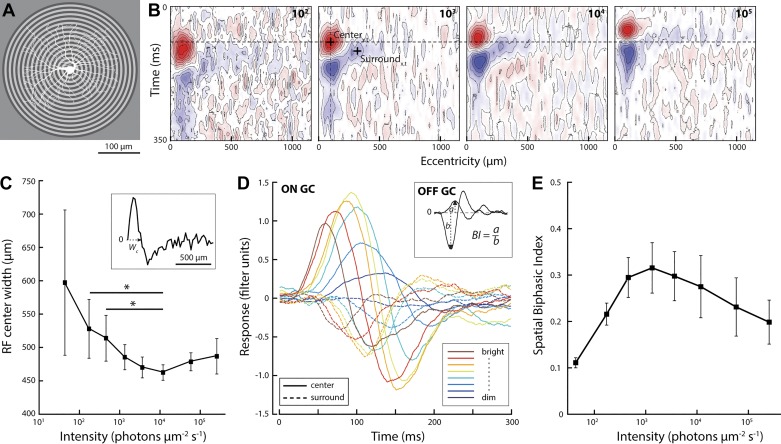

Fig. 4.

Bright light reduces surround inhibition of the ganglion cell response. A: schematic of the circular white noise stimulus used to measure spatiotemporal receptive fields of retinal ganglion cells (example ganglion cell morphology overlaid in white). Luminance of each circle was updated every 33 ms according to a random binary sequence. B: space-time plot of an example ganglion cell spatiotemporal receptive field measured with the circular white noise stimulus. Because annulus area increased with eccentricity, the third or fourth annulus typically showed the strongest positive correlation with the cell’s spike response (excitatory center, red). Negative correlations (inhibitory surround, blue) were strongest ~250 µm from the receptive field center. C: width of the receptive field center, defined as the zero crossing of the spatial response profile (wc; see inset; n = 8). *P = 0.02; t-test, all other P = 0.16–0.54, not significant). D: temporal filters of the receptive field center and surround (peak and trough in the spatial reverse correlogram; + in B) at different light levels (single-cell example; solid lines, center; dotted lines, surround). E: biphasic index of ganglion cell filters (black line; n = 8: 6 OFF, 2 ON). The spatial biphasic index was calculated as the ratio of the peak amplitude of the center and surround filter measured at each light level (see inset in D).

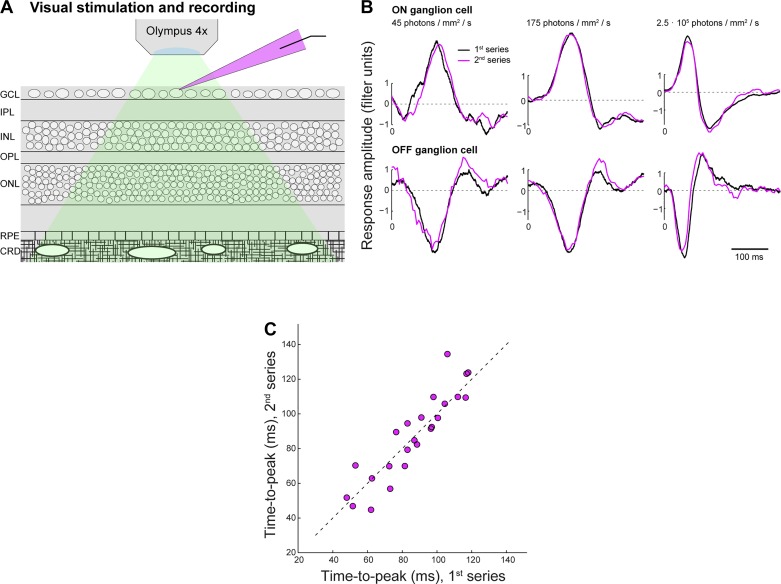

Measuring a cell’s spatiotemporal filter at all light levels required ~30 min of stable recording. This was readily achieved for both horizontal cell and ganglion cells. The retina remained attached to the sclera and pigment epithelium throughout the experiment, leaving intact metabolic pathways required for photopigment reactivation to prevent depletion of the photopigment. Indeed, control experiments, where the entire series of white noise stimulation at eight light levels was presented twice (see Fig. 7) showed that changes in visual responses with increasing light level were reversible. This demonstrates that the highest light levels used in our preparation did not cause persistent changes in visual sensitivity of the retina.

Fig. 7.

Visual sensitivity of the retina-with-choroid in vitro preparation is robust to stimulation at high light intensities. A: horizontal cell and ganglion cell recordings in this study were obtained from the whole mount guinea pig retina with intact retinal pigment epithelium and choroid (GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; CRD, choroid). Green shading indicates the stimulus light path; magenta shading indicates the glass recording pipette with Alexa 568. B: to test if changes in visual responses observed at high light levels are reversible, we presented the entire stimulus light-level series twice and compared temporal filters computed from responses recorded during the 1st (black) vs. 2nd series (magenta). Panels show overlay of filters at lowest two light levels and at the highest light level for a single example ON (top) and OFF cell (bottom). C: population data comparing filter time to peak at all 8 light levels during the 1st vs. 2nd recorded series for all recorded cells (n = 3). These data indicate that filter changes with increasing light level are reversible and that visual sensitivity is robust against the high light levels used in the experiments.

Definition of light levels.

Rods in guinea pig (like other nonprimate species) do not saturate but adapt and contribute to the cone signaling pathway throughout the photopic range (Yin et al. 2006). We define the mesopic/photopic border as the point where cones begin to adapt, i.e., 3 log units above the scotopic/mesopic border. This is consistent with the mesopic/photopic border in primates, where rods saturate and cones start to adapt. As background illumination increases, signals of rods mix in different proportions with the signals from cones, from nearly 100% rod in the low-mesopic range to 20% rod in the mid-photopic range (Yin et al. 2006). Rod signals in the low-mesopic to high-photopic range used in this study reach the ganglion cells through the cone pathway and will therefore similarly activate center-surround and adaptation mechanisms. The rod bipolar pathway contribution tapers out in the lowest log unit of the mesopic range (Stockman and Sharpe 2006; Troy et al. 1999). Because the principal results pertain to high light levels, our description of results focuses on adaptive changes in the cone signaling pathways.

Data analysis.

Neural filters were computed numerically in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) by cross-multiplying and summing vectors representing the stimulus and membrane voltage response (horizontal cells) or the stimulus and spike response in 4-ms bins (ganglion cells; Chichilnisky 2001). Performing this operation with relative time offsets of 0–500 ms (4-ms steps) between the two vectors gave for each cell a linear filter characteristic with a 4-ms time base. Filters were computed using the entire recorded response (~3-min duration) at each light level. Omitting up to 25 s of the initial response to avoid potential nonstationarity following a light-level change negligibly affected the computed filter properties, including filter shape, amplitude, or time to peak. Analysis of filters for horizontal cells, calculated from subsequent 2.5-s response fragments, showed that time to peak was stable from the initial response fragment onward; an ~15% gain change during the first 25 s in horizontal cells at the highest light level impacted the amplitude of the calculated filter less than 4% due to the total duration of the recordings.

To compute the static nonlinear response function at each light level, we generated a linear response prediction by convolving the stimulus with the filter and plotting this linear prediction against the measured response, averaged in 100 equal-sized bins.

Quantifying filter characteristics.

To quantify filter time to peak and amplitude of the peak and opponent peak, we first located the maximum (ON ganglion cells) or minimum (OFF ganglion cells and horizontal cells) within a filter time window of 20–250 ms. After the peak was located, the opponent peak was located, defined as the first zero-crossing of the derivative of the filter waveform following the peak, computed numerically as r′(ti) = r(t) – r(ti−1) over tpeak – t250 ms. Filter time to peak and amplitude of peak and opponent peak were obtained from a polynomial fit with high temporal resolution (0.1 ms) centered on the filter peak and opponent peak. The use of a polynomial fit made these measures robust against spurious local fluctuations and allowed estimates of time to peak with temporal resolution exceeding the filter’s 4-ms time base.

Filter shape was quantified with the biphasic index,

| (1) |

where a1 and a2 are the absolute amplitudes of the first and second (opponent) peak of the linear filter, with the opponent peak defined as the first sign reversal of the derivative of the filter waveform following the first filter peak. As for the first peak, amplitude and timing of the opponent peak were measured using a polynomial fit centered on the opponent peak. Accuracy of the fits to peak and opponent peak timing and amplitude was confirmed by visual inspection of each filter in a 0- to 1,000-ms time window. The biphasic index ranges from 0 for a true monophasic filter (excitatory phase only) to 1 for a biphasic filter with excitatory and inhibitory response phases of equal amplitude. At all light levels, the biphasic index measured for horizontal cell and ganglion cell filters fell between these extremes.

Model fits to the ganglion cell spatial filters (see Fig. 5, D–F) were obtained by minimizing the root mean square (RMS) error (least-squares function in MATLAB) between the measured filters and a difference-of-Gaussians spatial weighting function, R(x,y) = s·(center − surround), with and . Free parameters of the fit were s, a global scale factor; σc, the center width; a, the relative surround width; and k, the relative surround amplitude.

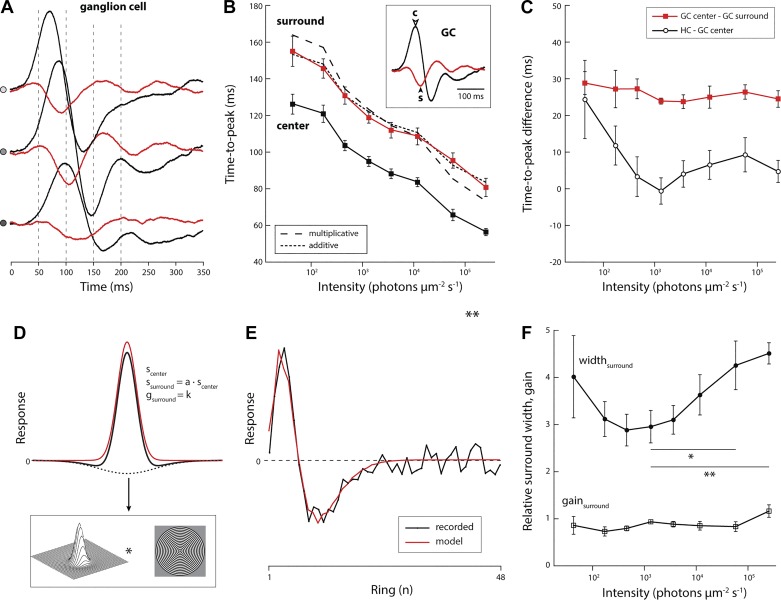

Fig. 5.

Filters representing center and surround speed up in parallel whereas filters representing outer and inner retina do not. A: temporal filters of the center (black) and surround (red) of an ON-type ganglion cell at 3 different light levels (top, 2.5 × 105; middle, 1.2 × 104; bottom, 4.7 × 102 photons·μm−2·s−1). B: time to peak of filters representing the center and surround of all ganglion cells recorded with the spatial white noise stimulus (both ON- and OFF-type cells; n = 8). Two models were tested to describe the difference between center and surround time to peak: an additive model, where the delay was constant (dotted line), and a multiplicative model, where the delay was a fixed fraction of the center time to peak (dashed line). C: difference of center and surround time to peak for the spatial receptive field data shown in B (red; n = 8) and difference in time to peak of the average horizontal cell and ganglion cell filter (black; data shown in Fig. 3A). Receptive field center and surround parameters were obtained from a model fit to the recorded data. D: illustration of the fit procedure. Measured receptive fields (corrected for changes in annulus area) were fit with a difference-of-Gaussians function. Free parameters are the width of the center Gaussian (scenter), relative width of the surround Gaussian relative to the center Gaussian (a), relative strength of the surround Gaussian (k), and a global scale parameter to match the difference-of-Gaussians waveform to the measured filters. E. Fit parameters were obtained by minimizing the root mean square error between the receptive field profile computed from the predicted response to the circular white noise stimulus and the receptive field profile computed from the recorded response to the circular white noise stimulus. F: relative surround width and amplitude, measured at the time when the center response peaked, obtained from the model fits at different light levels (values represent ratio of surround to center; n = 8). The increase in surround width in bright light is significant (relative values compared with width at 3.6 × 103 photons·μm−2·s−1; t-test, *P = 0.005; **P < 0.001).

Model of ganglion cell receptive field dynamics.

We present a computational model that recapitulates the ganglion cell center and surround temporal dynamics from the dimmest through the bright light level used in our experiments. The model generates a wave shape for the center and surround responses from a modified “alpha” function (4th order in time) with different delays and response time constants for center and surround. The model has six parameters. Of these, two define the excitatory center wave form (center response delay, center time constant factor), two define the inhibitory surround wave form (surround response delay, surround time constant factor), one defines the strength of the surround relative to the center (relative surround gain), and one scales the filter after subtraction of the excitatory and inhibitory waveform to match the relative amplitudes to the measured filters across light levels (overall gain). Time constant and delay of the surround were set to be fixed relative to those of the center. Thus, of these six parameters, the values of four were varied with light level to obtain the filters shown in Fig. 6B.

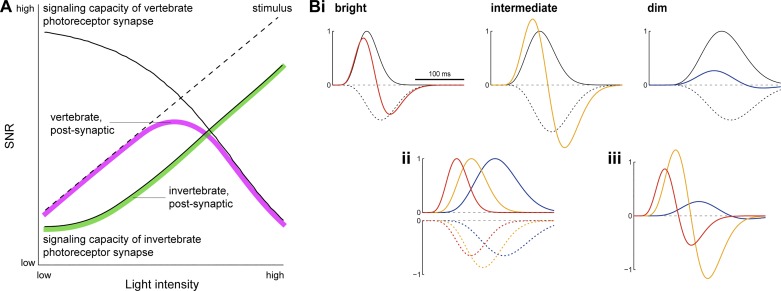

Fig. 6.

A: hypothetical model of light level-dependent changes in SNR in the vertebrate retina. Schematic shows the presumed bounds to SNR set by the visual signal and photoreceptor synapses of vertebrates and invertebrates. In all organisms, SNR in the retina (green, magenta) is constrained by SNR of the visual input (dashed line) and SNR in the neurons that receive and transmit this input (photoreceptors; solid lines). In the eye of invertebrates, with increasing light, SNR of the visual input and SNR of the photoreceptor synaptic output grow in parallel, because increasing photon flux increases the rate of synaptic vesicle release (assuming Poisson noise). In vertebrates, the expected pattern is different, because increasing photon flux decreases the rate of synaptic vesicle release. In dim light, stimulus SNR limits retinal SNR, whereas in bright light, due to the low rate of synaptic vesicle release, synaptic SNR limits retinal SNR. We postulate that the cone synapse limits SNR in postsynaptic retinal neurons, causing retinal SNR in vertebrates to peak at an intermediate light level, consistent with the results. B: a hypothetical model (see methods for details) recapitulates observed changes in ganglion cell filter time course across light-adapted states. i, Opponent monophasic filters with different time course and amplitude, representing interacting excitatory (solid black) and inhibitory signals (dashed, black) and combined by subtraction, approximate the observed changes in ganglion cell filter characteristics at different light levels (see Figs. 2B, 2C, and 4D: bright, red; intermediate, yellow; dim, blue). ii, Overlay of the excitatory (top) and inhibitory (bottom) filters in bright, intermediate, and dim light shown in i. iii, Overlay of the resultant filters in bright, intermediate, and dim light shown in i. Similar to the measured ganglion cell filter values (Fig. 5, B and C), the temporal delay between the peak of the combined (center; colors) filter and the peak of the opponent (surround; black dashed) filter is approximately constant at ~35 ms. Amplitude of the resultant filter at each light level was adjusted with an overall gain factor to match the measured filters.

Values for the center response delay were 30, 20, and 10 ms (dim, intermediate, and bright light, respectively), derived from the initial rise of the real data filter. The fixed additional surround delay was 4 ms. Values for the time constant factors were 0.007, 0.0032, and 0.0018 (dim, intermediate, and bright light, respectively). Values for the relative surround gain were −0.65, −0.87, and −0.65 (dim, intermediate, and bright light, respectively). Values for the overall gain were 0.6, 2.8, and 1.3 (dim, intermediate, and bright light, respectively), applied by multiplication of the resultant filter after subtraction of center and surround waveforms and set to approximate the measured filter data shown in Fig. 4D.

The model filters (see Fig. 6B) were computed as follows. Excitatory center signal c(t) = t − center delay; inhibitory surround signal s(t) = t − surround delay, where surround delay = center delay + 4 ms. Center waveform Rcenter = c(t)4·(center time constant factor)2·exp[−c(t)2·(center time constant factor)]; and surround waveform Rsurround = s(t)4·(surround time constant factor)2·exp[−s(t)2·(surround time constant factor)]·surround gain. Subtracting the surround from the center and wave forms and scaling gives the resultant filter representing the ganglion cell receptive field: FGC = (Rcenter − Rsurround)·(overall gain).

Statistics.

Error bars represent means ± SE, unless stated otherwise.

RESULTS

We recorded visually evoked responses from 20 A-type horizontal cells and 13 brisk-transient ganglion cells (3 ON-type and 10 OFF-type cells) stimulated with spatiotemporal white noise in a total of 31 whole mount retinas obtained from 22 guinea pigs. Stimulus contrast was kept constant (70% Michelson contrast) while mean intensity (light level) was varied over a 3.5-log10 unit range, from low to high photopic light levels. From the white noise response recorded at each light level, we calculated for each cell a linear response characteristic (“filter”) and static nonlinear transfer function (“static nonlinearity”) using existing methods (Chichilnisky 2001).

Response range and modulation amplitude.

From the lowest to the highest light level tested, the time-averaged membrane potential in horizontal cells decreased monotonically from −30.0 ± 0.6 to −64.7 ± 2.8 mV (n = 8; Fig. 1A). The decrease was negligible at intensities <103 photons·µm−2·s−1 and approximately proportional to log-intensity from 103 to 105 photons·µm−2·s−1 (Fig. 1B). In response to full-field white noise superimposed on the highest background intensity, membrane voltage did not hyperpolarize beyond −73 mV (Fig. 1A), where an apparent lower bound to the membrane potential rectified the light-evoked response. These data show that the light levels applied spanned the operating range of light adaptation at the level of the horizontal cells.

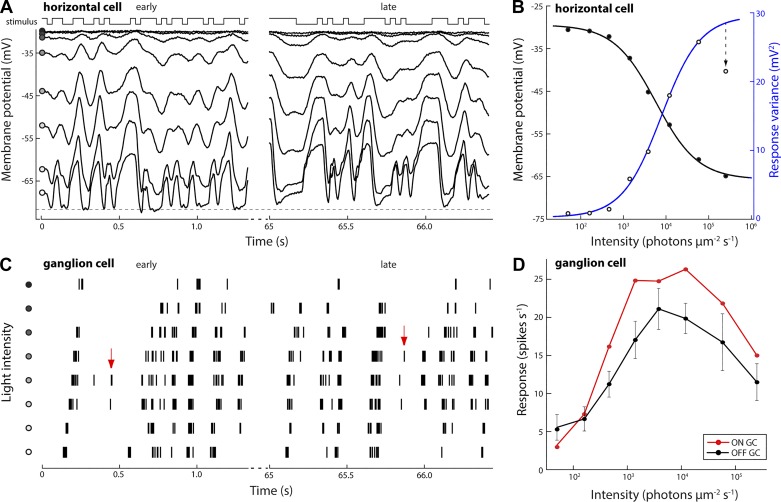

Fig. 1.

Response amplitudes of horizontal cell and ganglion cell visual responses are reduced at low and at high light levels. A: intracellular response of an A-type horizontal cell stimulated with full-field binary white noise at different mean light levels. Traces show sections of the recorded response immediately following a light level change (t = 0; early) and 65 s later (late). The same white noise sequence was used at each light level. Circles, from dark to light: 4.0 × 101, 1.7 × 102, 4.6 × 102, 1.3 × 103, 3.6 × 103, 1.2 × 104, 5.8 × 104, and 2.5 × 105 photons·μm−2·s−1; 70% Michelson contrast. Dashed line indicates an apparent limit to the recorded cell’s hyperpolarization at −73 mV. B: average membrane voltage (filled circles, black) and modulation amplitude (open circles, blue) of horizontal cell responses at each light level. Black and blue traces are sigmoidal fits to the data: y = a + (b − a)/{1 + e[−d(x − c)]}, where a and b are the respective lower and upper asymptotes, c is the half-rise point, and d defines the steepness. Modulation amplitude of the recorded response was reduced at the highest light level (arrow). C: extracellular spike response of an OFF-type ganglion cell stimulated with spatiotemporal binary white noise. Vertical lines represent spikes; rows represent the response recorded at each light level (same levels as in A). Arrows indicate stimulus features were signaled at intermediate light levels but not at low or high light levels. D: average ganglion cell response rates during white noise stimulation at each light level (n = 7 cells).

Rectification of the white noise response in horizontal cells was maximal immediately following an increase in background intensity to the highest light level but recovered through light-adaptive changes acting on a timescale of tens of seconds (Fig. 1A, compare early vs. late). Modulation amplitude of the horizontal cell response increased monotonically from dim to bright light, except at the highest light level, where the response amplitude was significantly reduced (Fig. 1B; t-test, P < 0.001, n = 8).

Presented with the same stimulus, at the level of the retinal output, the response rate of alpha-type ganglion cells increased from 9.0 ± 2.7 spikes/s in dim light to a peak of 34.2 ± 4.4 spikes/s at ~104 photons·µm−2·s−1 (Fig. 1, C and D) and with further light increase fell to 18.6 ± 3.9 spikes/s. Similar to the results obtained from horizontal cells, both ON and OFF alpha ganglion cells showed reduced response amplitudes at the highest light intensity (t-test, both P < 0.001; Fig. 1D).

Horizontal cell and ganglion cell filters from dim through bright light.

Next, we asked how spatiotemporal integration in horizontal cells and alpha-type ganglion cells changes as a function of light level. To answer this, we used the white noise responses recorded from horizontal cells and ganglion cells to compute for each cell a linear filter (Fig. 2, A–C) and a static nonlinearity (Fig. 2, D–F) approximating their response characteristics at each light level. The linear filter reflects the spatiotemporal frequency response function, whereas the static nonlinearity reflects the relative sensitivity (contrast gain) across stimulus conditions and can be used to identify response nonlinearities, including rectification and saturation. For each light level, the static nonlinearity computed represents the average response nonlinearity across the 3-min recording. As such, it does not show potential changes in nonlinearity on a slow (10–100 s) timescale. The following section describes light-adaptive changes in the filter and static nonlinearity, concentrating on the features most pertinent to the encoding of spatiotemporal luminance contrast.

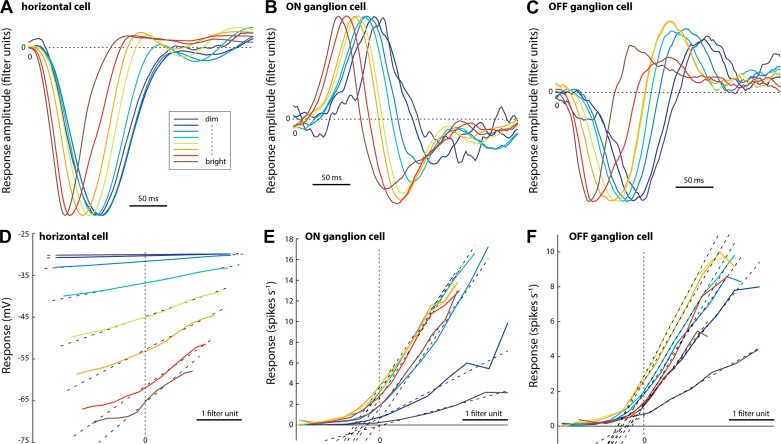

Fig. 2.

Light adaption impacts both linear and nonlinear response properties of horizontal cells and ganglion cells. A–C: temporal response characteristics (linear filters) of a horizontal cell (A), an ON-type ganglion cell (B), and an OFF-type ganglion cell (C). Each panel shows a single-cell example representative of the recorded population. Filters were calculated from the response to binary white noise (70% contrast) at different mean light levels (for values, see Fig. 1A legend). Filter amplitude is normalized to the first peak. D–F: static nonlinear transfer functions (see methods) obtained using the linear filters shown in A–C. Dotted lines show linear fits to the data from 15% to 85% of the cell’s dynamic response range used to measure contrast gain and response linearity at each light level.

Light-adaptive changes in temporal dynamics in outer and inner retina.

First, we compared how time to peak of the linear filter of horizontal cells and ganglion cells changed from dim to bright light. Analysis showed that nonstationarity apparent in the horizontal cell response at the highest light level (Fig. 1A, compare early vs. late) did not affect filter time to peak and impacted filter amplitude <4%. Therefore, filters were computed using the entire ~3-min recording at each light level. Over the dimmest 1.5 decades, horizontal cell time to peak remained approximately constant at 109 ± 7.2 ms (n = 20). Over the next two decades, time to peak fell at a constant rate of 20.5 ms per decade (Fig. 3A). Measured with the same stimulus and across the same intensity range, time to peak of ganglion cell filters decreased monotonically (Fig. 3A). At the lowest light levels, time to peak fell at a constant rate of 24.1 ms per decade, leveled off around 3.5 × 103 photons·µm−2·s−1 (approximately the light intensity where light adaptation shifts from the inner to the outer retina; Dunn et al. 2007), and at higher light levels continued to fall at a constant rate of 18.9 ms per decade (n = 12). Above ~1.4 × 103 photons·µm−2·s−1, the ratio of horizontal cell to ganglion cell time to peak was approximately constant (0.93 ± 0.07) and the difference in time to peak small, just 4.5 ± 4.1 ms.

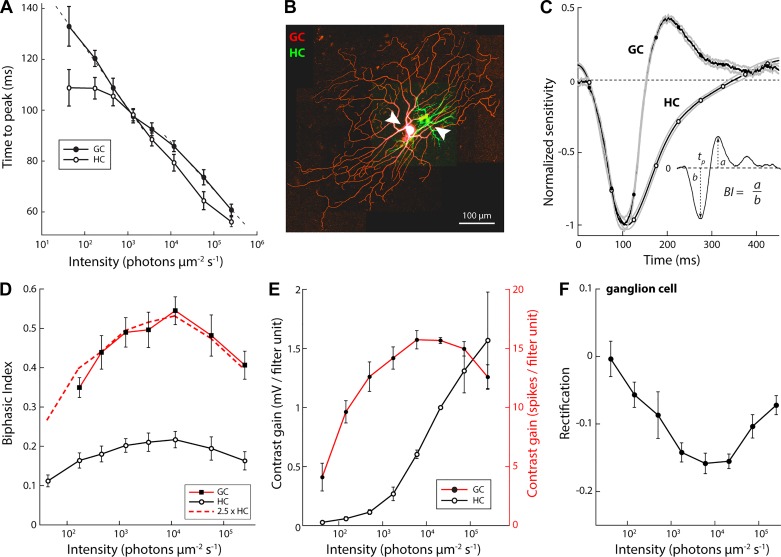

Fig. 3.

Response timing and amplitude adapt independently. A: filter time to peak (tp, see inset in C) for horizontal cells (n = 20) and ganglion cells (n = 12: 2 ON and 10 OFF) across light-adapted states. Dotted lines show linear fits to the ganglion cell time to peak in dim and bright light; respective slopes = 24.1 and 18.9 ms per log10 unit. B: Z projection of a confocal fluorescence image stack of a simultaneously recorded horizontal cell (HC) and OFF-alpha ganglion cell (GC; green Alexa Fluor 488; red, Alexa Fluor 568). C: temporal filters of the simultaneously recorded horizontal cell and ganglion cell pair shown in B. Inset shows calculation of the biphasic index (BI). D: biphasic index (ratio of peak of the inhibitory and excitatory response phase; see inset in C) for horizontal cells (n = 20) and ganglion cells (n = 12: 2 ON and 10 OFF). The horizontal cell and ganglion cell biphasic index differed by ~2.5-fold at all levels. E: light-adaptive changes in contrast gain (slope of the static nonlinear transfer function; see Fig. 2, D–F) of horizontal cells and ganglion cells. F: light-adaptive changes in rectification (the contrast value below which no spikes are fired; x-axis intercept of the linear fit to the static nonlinear transfer function, see Fig. 2, D–F) of the ganglion cell response.

Simultaneously recorded concentric horizontal and ganglion cell pairs (Fig. 3B) showed a close match in the initial falling phase of the cells’ temporal filters (Fig. 3C). During the subsequent rising phase, the ganglion cell filter transitioned sharply into an opponent response phase, whereas the horizontal cell filter showed a relatively slow return to baseline. The same was observed in all recorded pairs (n = 4).

These data show close agreement between the time to peak, and therefore temporal bandwidth, of horizontal cell and ganglion cell responses, except at the lowest light levels, where time to peak in ganglion cells is significantly longer than in horizontal cells, indicating increased temporal integration.

Light-adaptive changes in filter shape.

To assess the frequency response characteristics of horizontal cells and ganglion cells across light-adapted states, we quantified the shape of their respective filters across light levels with the biphasic index, defined as the ratio of the amplitudes of a filter’s net activating and inactivating response phases (Fig. 3C, inset). Relatively weak inactivation results in a low biphasic index and indicates a low-pass frequency response; relatively strong inactivation results in a high biphasic index and indicates a band-pass frequency response.

Biphasic indexes of horizontal cells and ganglion cells varied with light level (Fig. 3D). For horizontal cells, the biphasic index was lowest in dim light, peaked at 1.2 × 104 photons·µm−2·s−1, and decreased at higher light levels (Fig. 3D). The biphasic index for ganglion cells showed a similar dome-shaped curve (Fig. 3D), but at all light levels the biphasic index for ganglion cell filters was higher than for horizontal cell filters. Furthermore, the same change in light level evoked a larger change in the biphasic index in ganglion cells compared with horizontal cells. Overall, biphasic indexes of ganglion cells and horizontal cells differed by ~2.5 fold, and this ratio was nearly constant across the tested range of light-adapted states (Fig. 3D, red curve), indicating that filter characteristics scaled approximately proportionally across the tested range.

Light-adaptive changes in contrast gain and rectification.

Next, we asked how light adaptation affects horizontal cell and ganglion cell response gain and rectification. Gain expresses how much a cell’s output changes per unit change in the input; rectification is a measure of the cell’s response threshold, set by biophysical constraints including the spike threshold and reversal potentials of ion channels expressed in the cell membrane. To measure these parameters, we computed static nonlinear transfer functions for each cell type (Fig. 2, D–F). Because horizontal cells showed no substantial rectification except during the first ~20 s following a light-level increment to the highest light level (Figs. 1A and 2D), we quantified rectification only for ganglion cells.

The response gain of horizontal cells in dim light was low across the lowest 1.5 log units of intensity and increased nearly proportional to log intensity, with negligible saturation at high light levels (Fig. 3E). The response gain of ganglion cells rose sharply from the dimmest light level upward, peaked in the mid-photopic level, and decreased again at higher light intensities (Fig. 3E).

In both ON and OFF type ganglion cells, rectification, defined as the stimulus contrast value below which no spikes were fired, was strongest in dim light (Fig. 3F). Increasing light levels increased the firing rate at 0% contrast, which permitted additional, nonpreferred contrast values to be signaled. Thus, with increasing light, rectification decreased and the ganglion cell contrast response range expanded. However, at the highest light intensities, the spike rate at 0% contrast decreased again, in both ON- and OFF-type cells, and rectification increased (Fig. 3F). The observed decrease in response range in ganglion cells at high light levels is consistent with the decrease in average spike rate reported earlier (Fig. 1C). The observed changes in ganglion cell response nonlinearities are consistent with hypothesized changes in SNR.

The monotonic dependence of the horizontal cell contrast gain on background light level indicates that compared with the ganglion cell, the horizontal cell response adapts less strongly to mean light level and, therefore, more closely follows the absolute changes in intensity of the visual stimulus. Thus increasing contrast gain of the horizontal cell transfer functions at increasing light levels is driven by the greater absolute change in intensity of the visual input with constant contrast at higher background levels (e.g., a 70% increase from a low background light level comprises a smaller intensity change compared with a 70% increase from a high background light level).

Light-adaptive changes in ganglion cell spatial filters.

If spatial adaptation follows the same rules as temporal adaptation, then the spatial biphasic index, too, should be low in dim light, peak at an intermediate light level, and be low again at high light levels. To test this, we measured ganglion cell spatial receptive fields with a circularly symmetric white noise stimulus (Fig. 4, A and B). Centered on a cell’s receptive field, this stimulus presented equivalent luminance contrast at each eccentricity. Circular white noise drove cells more strongly than a square “checkerboard” stimulus and allowed us to measure their spatiotemporal receptive fields quickly (<5 min) and with high spatial resolution (~25 µm).

Spatial receptive fields obtained from the circular white noise recordings were quantified through a least-squares fit with two linearly summed spatially antagonistic filters, representing receptive field center and surround, whose relative strengths and size were allowed to vary. Width of the spatial receptive field center was defined as the diameter of the fitted receptive field profile at the zero crossing. The average center width was 597 ± 108 µm in dim light. Width decreased to 463 ± 11 µm in the mid-photopic range, where the receptive field was at its narrowest (29% change), and did not change significantly at higher light levels (width = 487 ± 27 µm at the highest light level tested; paired t-test, P = 0.24, n = 6; Fig. 4C). For all cells, the spatial biphasic index (ratio of peak surround amplitude to peak center amplitude) was lowest in dim light, peaked at an intermediate light level, and decreased again with further increases in light intensity (Fig. 4, D and E). Collectively, these data show that both temporal and spatial filters become increasingly monophasic at high light levels.

Temporal dynamics of receptive field center and surround.

Results thus far demonstrate how light adaptation changes five basic properties of the horizontal cell and ganglion cell response: dynamic range, filter speed, filter shape, response gain, and rectification. In both cell types, light-adaptive changes to filter shape followed a dome-shaped function indicative of low-pass filtering in dim as well as bright light and band-pass filtering at intermediate light levels. Adaptive changes in filter shape in ganglion cells were ~2.5-fold larger compared with those in horizontal cells (Fig. 3D), indicating that an inner retinal mechanism contributes to the ganglion cell biphasic response. We explored this further by studying light adaptive changes in the ganglion cell center and surround.

The biphasic index expresses the relative strength of a neuron’s activating and inactivating response phase. Therefore, it reflects how a neuron filters the transmitted signal. Several mechanisms can generate a biphasic neuronal response and contribute to it, including synaptic depression, opening of potassium channels, and the interaction of excitatory and inhibitory inputs at the level of the outer and inner retina. In this study we asked how the latter mechanism might contribute to the observed receptive field changes in our measurements. Driven by excitatory-inhibitory interactions, the biphasic response waveform depends not only on the relative strengths of the excitatory and inhibitory inputs but also on their overlap. As such, the biphasic index does not constrain the underlying response components: for example, expressed as a linear filter, strong near-coincident inhibition would appear similar to weak delayed inhibition. To address this ambiguity, we compared the temporal dynamics of excitatory center and inhibitory surround responses across light-adapted states.

We compared time to peak of the temporal filter measured in the receptive field center and receptive field surround (Fig. 5A). For the center, we used the temporal filter at the eccentricity that gave the largest excitatory amplitude, and for the surround, we used the temporal filter at the eccentricity that gave the largest inhibitory amplitude. The peak response of the excitatory center always preceded that of the inhibitory surround (Fig. 5B). The average surround lag was 25.9 ± 1.8 ms; expressed as a fraction, the surround response peaked 30.0 ± 6.0% after the center.

Across 3.5 decades of intensity, the lag between the peak center and surround response changed less than 5 ms (range 23.8–28.8 ms; Fig. 5C), despite a more than 70-ms change in time to peak (Fig. 5B). To determine whether the lag of inhibition is due to an additive or a multiplicative mechanism, we asked whether the temporal offset between center and surround time to peak was best approximated by a constant offset (additive lag) or a constant ratio (multiplicative lag). To answer this, we compared two predictive computational models. In the additive model, the average lag was added to each measured center latency; in the multiplicative model, each measured center latency was multiplied by the average ratio of surround to center time to peak across light levels (Fig. 5B). The additive model prediction was nearly threefold more accurate than the multiplicative model (RMSE: 2.5 vs. 7.1, respectively). Thus the surround response lags the center response with a delay that is nearly constant. A functional consequence of this particular arrangement is that it renders temporal interactions following center and surround stimulation largely independent of the light-adapted state of the circuit.

Finally, a two-dimensional Gaussian fit (see methods for details) to the ganglion cell spatial receptive field across light levels showed that the light-adaptive change to the spatial receptive field consists primarily of changes in the width of the surround relative to the center (Fig. 5, D–F).

DISCUSSION

Light adaptation is essential for visual function under changing luminance conditions. We asked how retinal neurons adapt at high light levels, where we expect SNR of the photoreceptor output to be reduced due to a low rate of synaptic vesicle release (Choi et al. 2005). To answer this question, we measured light-adaptive changes in the response properties of horizontal cells and ganglion cells and found that in both cell types, increasing illumination from a low to a high photopic level accelerated the neural response, shifted temporal (horizontal cells) and spatiotemporal (ganglion cells) tuning from low pass to band pass, and increased the response amplitude, consistent with increasing SNR and increased information transmission. However, at light levels >104 photons·µm−2·s−1, the observed changes in frequency tuning characteristics and response amplitude reversed. While responses continued to accelerate, both horizontal cells and ganglion cells showed reduced response amplitudes and increasingly low-pass tuning, consistent with reduced SNR of the neuronal input. The magnitude of light-adaptive changes of the biphasic index in ganglion cells was ~2.5-fold larger compared with that in horizontal cells, implying that key contributing mechanisms are located in the inner retina. Our results are consistent with postulated upper bounds to SNR at the level of the stimulus and its neuronal representation (Fig. 6A) and with information-theoretic rules for optimizing signal transmission through a noisy channel with limited bandwidth (Shannon and Weaver 1949).

The cone synapse limits SNR in bright light.

Horizontal cells provide continuous negative feedback onto the cone photoreceptors to improve signaling by controlling synaptic gain and by limiting changes in the tonic rate of release of synaptic vesicles (VanLeeuwen et al. 2009). If this feedback were complete (unit gain), then a persistent change in rate of release would be compensated perfectly, and the tonic rate of release would be constant. However, an increase in light level reduces the tonic rate of release so that mammalian cones at high light levels release fewer vesicles (Choi et al. 2005). Because a lower rate of release decreases signaling capacity, fidelity, and SNR, these changes necessarily impact responses in downstream neurons.

Previous work showed that at high light levels, contrast sensitivity in horizontal cells and ganglion cells is decreased (Borghuis et al. 2009). Rather than an artifact of the in vitro preparation or a consequence of pigment bleaching, we now speculate this may be due to reduced SNR at the cone synapse given the known decrease in tonic release with increasing light level (Choi et al. 2005). Our current results are consistent with reduced SNR at the cone synapse, suggesting an appropriate shift in spatiotemporal response properties of postsynaptic neurons to accommodate this reduction. In our working model, bright light increases relative synaptic noise at the cone output, because increasing light levels hyperpolarize the cone and thus reduce its synaptic rate of release (Choi et al. 2005). With the assumption of Poisson statistics (Chavez-Noriega and Stevens 1994; DeVries et al. 2006; Thoreson 2007), quantal fluctuations in synaptic vesicle release at high light levels (low tonic release rate) would increasingly mask the light-evoked signal, thus limiting SNR of the synaptic output.

An alternative explanation, that pigment bleaching at high photon flux gives an isomerization rate so low that SNR is set presynaptically, appears unlikely. First, because of the large number of photopigment molecules per cone outer segment, ~2 × 107 (Nikonov et al. 2006), even with 99% of the photopigment bleached, the photon capture rate would exceed the vesicle release rate by several orders of magnitude and therefore contribute negligibly to the noise level of the transmitted signal. In bright light, larger Poisson fluctuations in the vesicle release rate relative to the mean will negatively impact SNR of the synaptic output, in conjunction with contributions from other noise sources. Second, if bleaching reduces the isomerization rates in the outer segment, then the cone signal should mimic dim light conditions and all light-adaptive changes should reduce or reverse. However, this is not what we observed: horizontal cells remained hyperpolarized (Fig. 1A) and filter time to peak in both horizontal cells and ganglion cells increased monotonically up to the highest intensity tested (Figs. 3A and 5B; 2.5 × 105 photons·µm−2·s−1, equivalent to 4.5 log td), demonstrating that phototransduction was not limiting. Indeed, robust visual transduction under high-photopic conditions is consistent with measurements of isolated salamander cones, which showed no deviation from Weber adaptation in the circulating cone current at these same high light levels, ~105 photons·µm−2·s−1 (Burkhardt 1994; Soo et al. 2008). Thus we conclude that under bright light conditions, the cone outer segment responds but the synaptic capacity to transmit the visual signal is reduced.

Pupil extends the high-SNR regime in human vision.

Our results and known properties of cone synaptic release indicate that light levels exceeding 104 photons·µm−2·s−1 reduce signal quality within the retina. Because low signal quality impairs vision, this raises the question whether specific mechanisms act to avoid high light levels on the retina. One obvious mechanism would be the pupil, whose diameter in humans changes with light level and is known to serve at least two purposes. First, by opening in dim light, the pupil increases photon flux on the retina, which improves SNR at the level of the photoreceptors. Second, by closing in bright light, the pupil reduces optical aberrations and improves spatial resolution of the image on the retina (Laughlin 1992). The latter improvement peaks at a diameter ~2.3 mm (Campbell and Gubisch 1966); for a smaller pupil, increased diffraction outweighs the reduction in optical aberration and degrades the image projected onto the retina. Our data suggest that the pupil may serve yet a third purpose: to improve retinal SNR by reducing photon flux under bright light conditions, to maintain a higher rate of cone synaptic vesicle release. Calculations show that for luminance above 103 cd/m2, pupil constriction attenuates the falloff of SNR and extends the range of light levels where SNR is maintained by more than twofold. Because all visual function is ultimately limited by retinal SNR, we conclude that by reducing photon flux on the retina, the pupil improves vertebrate vision at the high end of naturally occurring light levels. Our results show that the decline in visual signal amplitude and bandwidth occurs at light levels above 105 photons·µm−2·s−1. This is near the light level where melanopsin begins to activate intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells implicated in control of the pupil (~106 photons·µm−2·s−1) (Do et al. 2009). Thus melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells are well poised to contribute to the strong pupil constriction that helps improve visual function in bright light.

Neural mechanism underlying changes in the ganglion cell biphasic index.

Our demonstration that the spatiotemporal receptive field of alpha-type ganglion cells adapts in accordance with reported changes in SNR across light levels (Borghuis et al. 2009) raises the question of how this adaptation is achieved at the synaptic and circuit level. A recent psychophysical study in humans reported noise-modulated gain control within the scotopic rod pathway that functions over a time course on the order of 100 s (Rudd and Rieke 2016). Other recent work showed that under fixed stimulus conditions, such as a particular light-adapted state, the response of some OFF-type ganglion cells is optimized for SNR when the strength of excitation and inhibition onto the ganglion cell scale with stimulus strength according to exponential functions with opposite sign, driven by the same input signal (Homann and Freed 2017). Whereas optimizing the ganglion cell response for SNR was shown to depend on specific functional relations between circuit parameters, how these parameters would be set appropriately across stimulus conditions, such as different light-adapted states, remains unclear (Homann and Freed 2017).

In our assessment of adaptation to hypothesized changes in SNR of the visual signal across light levels, we consider two alternative mechanisms. In the first, the adapting cell uses a direct measure of SNR, e.g., based on fluctuations in the membrane voltage. A fundamental problem with this model is that it does not explain how fluctuations in the membrane voltage (i.e., SNR) modulated by background level would be distinguished from responses to spatiotemporal contrast of the visual input. Therefore, we argue for a different model that is supported by our data and does not rely on a direct measure of SNR. In this model, spatiotemporal adaptation is driven by the change in tonic glutamate release from the photoreceptors following a change in light level (Choi et al. 2005).

First, we assume that shape of the ganglion cell spatiotemporal receptive field is determined by the interaction between a feedforward excitatory signal (cone→bipolar cell→ganglion cell) and inhibitory signals impinging on this signal at the level of both the outer retina (horizontal cell→cone) and the inner retina (amacrine cell→bipolar cell; amacrine cell→ganglion cell; Frishman et al. 1987). Because excitation drives the inhibition, in both the outer retina (cone→horizontal cell) and the inner retina (bipolar cell→amacrine cell), the inhibitory signal lags the excitatory signal, consistent with our data (Fig. 5B). When inhibition is weak, receptive field shape is dominated by the predominantly monophasic excitatory filter and the frequency response is low pass. This matches our data at low photopic light levels. When the strength of inhibition increases, its delayed, negative-going response waveform turns the receptive field shape increasingly biphasic, and the frequency response becomes band pass. This matches our data at intermediate light levels. The return to low-pass signaling at high photopic light levels follows from reduced inhibition, which causes the monophasic excitatory filter to dominate again.

We propose a working model in which the ganglion cell spatiotemporal receptive field is generated by temporal overlap between excitatory and inhibitory signals that interact by subtraction. The respective signals represent the cumulative sum of excitatory and inhibitory signaling in the outer and inner retina and are modeled as monophasic, fourth-order “alpha” functions (Fig. 6B) with time constant, temporal delay, and amplitude set to match the measured filters (Fig. 4D) at three background light levels (bright, intermediate, dim).

To recapitulate decreasing time to peak of the measured filters, the time constant of the excitatory signal decreases monotonically with increasing background level, and the time constant of the inhibitory signal is greater than the excitatory time constant by a fixed parameter. Temporal overlap of these two opponent signals causes the resulting filter to be biphasic. The model shows that to maintain the relatively constant delay between the center and surround peaks (Fig. 4, A and B, Fig. 5, A–C), the excitatory and inhibitory signals must have longer time constants than the resulting biphasic peaks. Indeed, in alternative models where the time constants of the excitatory and inhibitory signals are set to correspond directly to the timing of the biphasic peaks, the required delay between the center and surround is longer by 1.3- to 3-fold compared with the delay of the measured data. At all light levels, the inhibitory component has substantial overlap with the excitatory component, but at dim and bright light levels, the model requires the amplitude of the inhibitory signal to be lower, to cause the resulting filter wave shape to be less biphasic compared with that at the intermediate light level. Whereas the inhibitory component under these conditions still contributes to the overall response, evident from decreased response gain (Fig. 1D), the surround amplitude diminishes, resulting in a temporally and spatially increasingly monophasic, excitation-dominated receptive field.

Although the separate excitatory and inhibitory kernels that comprise the model were not directly measurable from the real data, the model shows how interacting low-order basis functions can generate the measured ganglion cell center and surround signals. A requirement for this model is that the strength of inhibition is decreased in bright light, which can be tested experimentally. Indeed, mechanisms that may cause the strength of the surround to decrease at high light levels have been reported in the literature and include shorter temporal integration, reduced signal amplitude, and increased transience of the excitatory response at high levels (Jarsky et al. 2011). Furthermore, a recent study showed a return of visual responses in rod photoreceptors at high light levels equivalent to the levels used in our study (Tikidji-Hamburyan et al. 2017). Whereas apparent rod signaling correlates with relatively monophasic response profiles in horizontal cells and ganglion cells in dim and bright light, whether and how the rod signal might drive these light adaptive changes remains unclear.

Prior reports of reduced contrast sensitivity in bright light.

Previous studies of adaptation in vertebrate retinas under scotopic (Dunn et al. 2006; Dunn and Rieke 2008; Enroth-Cugell and Shapley 1973) and photopic conditions (Derrington and Lennie 1982; Dunn et al. 2007; Frishman et al. 1987; Purpura et al. 1990) showed the transition from low-pass to band-pass filters expected for adaptation to dim and bright light. However, none of these studies reported a return to low SNR characteristics in bright light, as shown in the present study. The explanation is that the highest background intensities in those studies, up to 1,500 cd/m2 (typical peak brightness of CRT monitors is ~340 cd/m2, equivalent to 104 photons·µm−2·s−1), were below the high-intensity range where, according to our data, a low rate of release begins to limit postsynaptic SNR. With the assumption of a 2.0-mm pupil in humans, light levels in these studies did not exceed the mid-photopic range, an order of magnitude below the highest light level used in the present study and encountered under natural viewing conditions. Indeed, contrast gain and biphasic index in our experiments peaked around 1,000 cd/m2 and were significantly reduced only above 5,000 cd/m2 (105 photons·µm−2·s−1; Figs. 1, 3, and 5).

One study that tested adaptation at high photopic backgrounds also showed a decrease in ganglion cell sensitivity at high luminance (Virsu and Lee 1983). Furthermore, a psychophysical study that tested detection performance at light levels as bright as those used in the present study, 106 photons·µm−2·s−1 (Stockman et al. 2006), showed reduced cone response modulation in bright light. In the latter study, contrast sensitivity peaked around 4 log td (~5,000 cd/m2), consistent with our current and previous measurements (Borghuis et al. 2009).

Optimal retinal representation of visual stimuli.

At first thought, a dome-shaped function of visual sensitivity from dim through bright light conditions is surprising, because it counters supposed Weber adaptation in bright light. However, it follows the combined upper bounds set by quantal noise fluctuations in the stimulus at low light levels and at the first visual synapse at high light levels (Fig. 6A). Our results emphasize that functional differences between organisms in a specific component of their neural circuitry, for example, the contrast polarity of the photoreceptor light response, impact directly how signals are best represented and transmitted (Sterling and Laughlin 2015). Thus explaining neural circuit architecture and function in evolutionarily divergent organisms requires taking into account the specific characteristics of their unique biological parts.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01 EY08124 (to B. G. Borghuis), R01 EY028188 (to B. G. Borghuis), R01 EY016607 (to R. G. Smith), and R01 EY23766 (to R. G. Smith), National Science Foundation Grant IBN-0344678 (to C. P. Ratliff), and NIH Vision Training Grant T32 07035 (to C. P. Ratliff).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.G.B., C.P.R., and R.G.S. conceived and designed research; B.G.B. performed experiments; B.G.B., C.P.R., and R.G.S. analyzed data; B.G.B., C.P.R., and R.G.S. interpreted results of experiments; B.G.B. and C.P.R. prepared figures; B.G.B. drafted manuscript; B.G.B., C.P.R., and R.G.S. edited and revised manuscript; B.G.B., C.P.R., and R.G.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jonathan Demb and Peter Sterling for useful comments on the manuscript and Simon Laughlin for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- Atick JJ. Could information theory provide an ecological theory of sensory processing? Network 22: 4–44, 2011. doi: 10.3109/0954898X.2011.638888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atick JJ, Redlich AN. Towards a theory of early visual processing. Neural Comput 2: 308–320, 1990. doi: 10.1162/neco.1990.2.3.308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benardete EA, Kaplan E. The receptive field of the primate P retinal ganglion cell, I: Linear dynamics. Vis Neurosci 14: 169–185, 1997. doi: 10.1017/S0952523800008853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghuis BG, Ratliff CP, Smith RG, Sterling P, Balasubramanian V. Design of a neuronal array. J Neurosci 28: 3178–3189, 2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5259-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghuis BG, Sterling P, Smith RG. Loss of sensitivity in an analog neural circuit. J Neurosci 29: 3045–3058, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5071-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt DA. Light adaptation and photopigment bleaching in cone photoreceptors in situ in the retina of the turtle. J Neurosci 14: 1091–1105, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FW, Gubisch RW. Optical quality of the human eye. J Physiol 186: 558–578, 1966. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander D, Chichilnisky EJ. Adaptation to temporal contrast in primate and salamander retina. J Neurosci 21: 9904–9916, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Noriega LE, Stevens CF. Increased transmitter release at excitatory synapses produced by direct activation of adenylate cyclase in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurosci 14: 310–317, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichilnisky EJ. A simple white noise analysis of neuronal light responses. Network 12: 199–213, 2001. doi: 10.1080/713663221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Borghuis BG, Rea R, Levitan ES, Sterling P, Kramer RH. Encoding light intensity by the cone photoreceptor synapse. Neuron 48: 555–562, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrington AM, Lennie P. The influence of temporal frequency and adaptation level on receptive field organization of retinal ganglion cells in cat. J Physiol 333: 343–366, 1982. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH, Li W, Saszik S. Parallel processing in two transmitter microenvironments at the cone photoreceptor synapse. Neuron 50: 735–748, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do MT, Kang SH, Xue T, Zhong H, Liao HW, Bergles DE, Yau KW. Photon capture and signalling by melanopsin retinal ganglion cells. Nature 457: 281–287, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nature07682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn FA, Doan T, Sampath AP, Rieke F. Controlling the gain of rod-mediated signals in the Mammalian retina. J Neurosci 26: 3959–3970, 2006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5148-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn FA, Lankheet MJ, Rieke F. Light adaptation in cone vision involves switching between receptor and post-receptor sites. Nature 449: 603–606, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nature06150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn FA, Rieke F. Single-photon absorptions evoke synaptic depression in the retina to extend the operational range of rod vision. Neuron 57: 894–904, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enroth-Cugell C, Shapley RM. Adaptation and dynamics of cat retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol 233: 271–309, 1973. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman LJ, Freeman AW, Troy JB, Schweitzer-Tong DE, Enroth-Cugell C. Spatiotemporal frequency responses of cat retinal ganglion cells. J Gen Physiol 89: 599–628, 1987. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.4.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homann J, Freed MA. A mammalian retinal ganglion cell implements a neuronal computation that maximizes the SNR of its postsynaptic currents. J Neurosci 37: 1468–1478, 2017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2814-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarsky T, Cembrowski M, Logan SM, Kath WL, Riecke H, Demb JB, Singer JH. A synaptic mechanism for retinal adaptation to luminance and contrast. J Neurosci 31: 11003–11015, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2631-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin SB. Retinal information capacity and the function of the pupil. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 12: 161–164, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikonov SS, Kholodenko R, Lem J, Pugh EN Jr. Physiological features of the S- and M-cone photoreceptors of wild-type mice from single-cell recordings. J Gen Physiol 127: 359–374, 2006. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichl L, González-Soriano J. Morphological types of horizontal cell in rodent retinae: a comparison of rat, mouse, gerbil, and guinea pig. Vis Neurosci 11: 501–517, 1994. doi: 10.1017/S095252380000242X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purpura K, Tranchina D, Kaplan E, Shapley RM. Light adaptation in the primate retina: analysis of changes in gain and dynamics of monkey retinal ganglion cells. Vis Neurosci 4: 75–93, 1990. doi: 10.1017/S0952523800002789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd ME, Rieke F. Brightness in human rod vision depends on slow neural adaptation to quantum statistics of light. J Vis 16: 23, 2016. doi: 10.1167/16.14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon CE, Weaver W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Soo FS, Detwiler PB, Rieke F. Light adaptation in salamander L-cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci 28: 1331–1342, 2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4121-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan MV, Laughlin SB, Dubs A. Predictive coding: a fresh view of inhibition in the retina. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 216: 427–459, 1982. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling P, Laughlin SB. Principles of Neural Design. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2015. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262028707.001.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman A, Langendörfer M, Smithson HE, Sharpe LT. Human cone light adaptation: from behavioral measurements to molecular mechanisms. J Vis 6: 1194–1213, 2006. doi: 10.1167/6.11.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman A, Sharpe LT. Into the twilight zone: the complexities of mesopic vision and luminous efficiency. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 26: 225–239, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2006.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson WB. Kinetics of synaptic transmission at ribbon synapses of rods and cones. Mol Neurobiol 36: 205–223, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-0019-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikidji-Hamburyan A, Reinhard K, Storchi R, Dietter J, Seitter H, Davis KE, Idrees S, Mutter M, Walmsley L, Bedford RA, Ueffing M, Ala-Laurila P, Brown TM, Lucas RJ, Münch TA. Rods progressively escape saturation to drive visual responses in daylight conditions. Nat Commun 8: 1813, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01816-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy JB, Bohnsack DL, Diller LC. Spatial properties of the cat X-cell receptive field as a function of mean light level. Vis Neurosci 16: 1089–1104, 1999. doi: 10.1017/S0952523899166094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hateren JH. Theoretical predictions of spatiotemporal receptive fields of fly LMCs, and experimental validation. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 171: 157–170, 1992a. doi: 10.1007/BF00188924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Hateren JH. A theory of maximizing sensory information. Biol Cybern 68: 23–29, 1992b. doi: 10.1007/BF00203134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanLeeuwen M, Fahrenfort I, Sjoerdsma T, Numan R, Kamermans M. Lateral gain control in the outer retina leads to potentiation of center responses of retinal neurons. J Neurosci 29: 6358–6366, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5834-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virsu V, Lee BB. Light adaptation in cells of macaque lateral geniculate nucleus and its relation to human light adaptation. J Neurophysiol 50: 864–878, 1983. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Smith RG, Sterling P, Brainard DH. Chromatic properties of horizontal and ganglion cell responses follow a dual gradient in cone opsin expression. J Neurosci 26: 12351–12361, 2006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1071-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]