Abstract

The SCN5A-encoded voltage-gated mechanosensitive Na+ channel NaV1.5 is expressed in human gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells and interstitial cells of Cajal. NaV1.5 contributes to smooth muscle electrical slow waves and mechanical sensitivity. In predominantly Caucasian irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patient cohorts, 2–3% of patients have SCN5A missense mutations that alter NaV1.5 function and may contribute to IBS pathophysiology. In this study we examined a racially and ethnically diverse cohort of IBS patients for SCN5A missense mutations, compared them with IBS-negative controls, and determined the resulting NaV1.5 voltage-dependent and mechanosensitive properties. All SCN5A exons were sequenced from somatic DNA of 252 Rome III IBS patients with diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds. Missense mutations were introduced into wild-type SCN5A by site-directed mutagenesis and cotransfected with green fluorescent protein into HEK-293 cells. NaV1.5 voltage-dependent and mechanosensitive functions were studied by whole cell electrophysiology with and without shear force. Five of 252 (2.0%) IBS patients had six rare SCN5A mutations that were absent in 377 IBS-negative controls. Six of six (100%) IBS-associated NaV1.5 mutations had voltage-dependent gating abnormalities [current density reduction (R225W, R433C, R986Q, and F1293S) and altered voltage dependence (R225W, R433C, R986Q, G1037V, and F1293S)], and at least one kinetic parameter was altered in all mutations. Four of six (67%) IBS-associated SCN5A mutations (R225W, R433C, R986Q, and F1293S) resulted in altered NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity. In this racially and ethnically diverse cohort of IBS patients, we show that 2% of IBS patients harbor SCN5A mutations that are absent in IBS-negative controls and result in NaV1.5 channels with abnormal voltage-dependent and mechanosensitive function.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The voltage-gated Na+ channel NaV1.5 contributes to smooth muscle physiology and electrical slow waves. In a racially and ethnically mixed irritable bowel syndrome cohort, 2% had mutations in the NaV1.5 gene SCN5A. These mutations were absent in irritable bowel syndrome-negative controls. Most mutant NaV1.5 channels were loss of function in voltage dependence or mechanosensitivity.

Keywords: ion channels, molecular mechanisms, mutations, smooth muscle

INTRODUCTION

Voltage-gated ion channels organize the electrical activity that is critical for normal gastrointestinal (GI) smooth muscle function (6). Voltage-gated Na+-selective (NaV) channels have been reported in GI tract smooth muscle cells of rat fundus (33) and colon (45) and canine jejunum (42). The voltage-gated mechanosensitive Na+ channel NaV1.5 is encoded by the SCN5A gene and is present in rat jejunum and colon (7) and, importantly, in the smooth muscle cells and interstitial cells of Cajal (43) in human jejunum (21) and colon (35).

NaV channels contribute to GI smooth muscle electrical activity. Na+ replacement, block, or knockdown hyperpolarized the membrane potential and decreased the upstroke rate, frequency, and amplitude of the slow wave, which is essential for normal GI motility (3, 14, 22, 43). Specific shRNA knockdown of NaV1.5 in rat jejunum resulted in hyperpolarization of the membrane potential and significant decreases in the peak amplitude and half-width of the electrical slow wave (7).

In addition to being voltage-gated, NaV1.5 is mechanosensitive in human jejunum (41) and colon (35) and when heterologously expressed in HEK-293 cells (9). Mechanical stress alters several NaV1.5 voltage-dependent properties. It increases NaV peak currents, hyperpolarizes the half-points of voltage dependence of activation and inactivation, accelerates activation, and delays recovery from inactivation (9, 35, 43). NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity is important for GI function, since ranolazine, a drug that is well known to be associated with constipation (34), blocks NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity (10) in human colon smooth muscle cells and decreases contractile activity of human ascending colon (35).

Ion channelopathies are diseases that result from abnormal function of ion channels due to mutations in ion channel pore-forming or -associating proteins (5). In the heart, SCN5A channelopathies are linked to cardiac conduction disorders (1). It is intriguing that >65% of patients with cardiac conduction disorders due to SCN5A mutations that result in NaV1.5 channelopathies report symptoms consistent with functional GI diseases, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (25). Follow-up studies showed SCN5A mutations in 2.0–2.2% of IBS patients (8, 37). These IBS-associated SCN5A mutations result in functionally abnormal NaV1.5 in 77% of the cases, and 90% of those are loss of voltage-dependent function (LOF) (8).

The limitations of the previous studies were that mechanosensitivity was frequently not tested and the patient cohorts were homogeneously Caucasian. Therefore, the aims of this study were to determine SCN5A missense mutations in a racially and ethnically diverse cohort of IBS patients, to examine an IBS-negative cohort for the presence of IBS-associated SCN5A mutations, and to examine voltage dependence properties, kinetics, and mechanosensitivity of IBS-associated NaV1.5 mutations.

METHODS

Patient Recruitment and Sample Collection

IBS patients and IBS-negative controls were recruited primarily from community advertisement, but also from the functional GI clinic at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) between April 2007 and November 2012. Subjects were 18–70 yr of age and underwent a physical examination, and a medical history, including a history of cardiovascular disease, was obtained. IBS and bowel habit subtyping were determined by the Rome III diagnostic criteria (13) in the absence of other chronic GI conditions and confirmed by a clinician with expertise in IBS. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, substance abuse, abdominal surgery, tobacco dependence (≥½ cigarette pack per day), current psychiatric illness, and extreme (≥1 h/day) strenuous exercise. DNA extracted from salivary samples of IBS patients and healthy controls was processed and assessed by the UCLA Biological Samples Processing Core using a nucleic acid purification instrument (Autopure LS, Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN). All subjects were compensated for participating in the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at UCLA and the Mayo Clinic and was conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines regulating human subjects research.

Mutational Analysis

We used PCR, denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography, and DNA sequencing, as described elsewhere (8), to conduct a comprehensive mutational analysis of all 27 amino acids encoding SCN5A exons. Mutations causing IBS were nonsynonymous (i.e., amino acid-altering) with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of <0.1% according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project (n = 6,503) (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/).

To examine a body mass index- and sex-matched cohort of racially and ethnically diverse IBS-negative controls (n = 377) for the presence of mutations identified in the IBS patients, we used TaqMan assay (20) when available or Sanger sequencing when TaqMan assay was not available.

Expression Vector Construction and HEK-293 Cell Transfection

For each mutation, the appropriate nucleotide changes were engineered by site-directed mutagenesis into a construct containing the most common splice variant of SCN5A (hH1c1, GenBank AC137587) (27) to encode an altered Na+ channel α-subunit, NaV1.5, using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of the constructs and the presence of the desired mutation were verified by DNA sequencing. The primers used for mutagenesis are listed in Table 1. Wild-type (WT) (27) or mutant constructs were cotransfected with pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) into HEK-293 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), as described previously (8, 37). After overnight culture, transfected cells positive for green fluorescent protein (GFP) were selected for whole cell voltage clamp.

Table 1.

Primers used for mutagenesis

| Primer |

||

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| R225W | ccttccgagtcctctgggccctgaaaact | agttttcagggcccagaggactcggaagg |

| R433C | gaggagaaggaaaagtgcttccaggaggcca | tggcctcctggaagcacttttccttctcctc |

| R986Q | gtggtctcctgcagcagcggcctca | tgaggccgctgctgcaggagaccac |

| G1037V | accaggccaggtcacccccgggg | ccccgggggtgacctggcctggt |

| F1293S | gccaacaccctgggctctgccgagatgg | ccatctcggcagagcccagggtgttggc |

| S1700G | ccttcgccaacagcgtgctgtgcctcttc | gaagaggcacagcacgctgttggcgaagg |

Whole Cell Electrophysiology

Solutions.

The extracellular solution contained (in mM) 159 Cl−, 139 Cs+, 15 Na+, 4.7 K+, 2.5 Ca2+, 10 HEPES, and 5.5 glucose; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The intracellular solution contained (in mM) 125 CH3SO3−, 35 Cl−, 145 Cs+, 5 Na+, 5 Mg2+, 5 HEPES, and 2 EGTA; pH was adjusted to 7.0 with CsOH. Osmolality was 290 mmol/kg. The predicted liquid junction potential was subtracted during analysis.

Data acquisition.

Electrodes were pulled to a resistance of 2–5 MΩ from Kimble KG12 glass on a P97 puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and coated with heat-cured R6101 polymer (Dow Corning). Whole cell current data from HEK-293 cells dialyzed with intracellular solution were recorded with an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier, CyberAmp320, Digidata 1322A, and pClamp9.2 software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA).

Voltage-clamp protocols.

Electrophysiology protocols were previously designed and validated to test voltage-dependent function (8) and response to shear stress applied by flow of the bath solution at 10 ml/min (37). To measure steady-state activation only, cells were held at −120 mV and, every 250 ms, were stepped for 30 ms in 5-mV intervals from −100 through −10 mV. Families of current sweeps were recorded as averages of up to 20 consecutive runs, 6 s elapsed per run. To measure steady-state activation and inactivation, cells were held at −120 mV and, every 5 s, were stepped to a first test pulse from −120 through −30 mV for 2.9 s in 5-mV intervals and to a second test pulse of −30 mV for 100 ms. Peak currents (Ipeak) normalized to the equation

were fit with a sigmoidal three-parameter curve:

where x0 is V1/2, the voltage of half-activation or half-inactivation. Currents activated during the test pulse steps were fitted with a three-term weighted exponential equation:

in which three time constants represent one activation and two inactivation states of NaV1.5. Peak currents are expressed as a fraction of cell capacitance (pA/pF).

Analysis.

Data were analyzed with pClamp 10.5 (Molecular Devices), Microsoft Excel 2010 (Redmond, WA), and SigmaPlot 12.3 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Significance was assigned at P < 0.05 vs. wild-type SCN5A (Table 1) by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (Prism 5, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Unique SCN5A Mutations in a Racially and Ethnically Diverse IBS Patient Cohort

Women comprised 75% of the 252 IBS patients recruited for the study. The ethnic and racial makeup of this IBS patient cohort was diverse: 16% Hispanic ethnicity, 58% Caucasian, 15% African American, 11% Asian, 3% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 1% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 9% multi-racial, and 3% other (Table 2). The 377 IBS-negative control cohort had a similar female predominance (71%) and body mass index. This cohort was also racially and ethnically diverse, yet it was younger and consisted of fewer Caucasians (43%) and more Asians (25%) than the IBS cohort (P < 0.05, by nonparametric 2-tailed t-test for age or Fisher’s exact test for racial and ethnic demographics; Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient cohort characteristics

| Control | Total IBS | SCN5A Mutations | SCN5A Polymorphisms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, n (%total) | 377 (100) | 252 (100) | 5 (2.0) | 25 (10) |

| Median age, yr (range) | 27 (18–63) | 34 (18–70)** | 30 (20–41) | 37 (19–70) |

| Median BMI, kg/m2 (range) | 24.0 (15.7–46.7) | 24.1 (15.7–41.7) | 25.4 (15.7–35.8) | 24.6 (18.9–34.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 266 (71) | 189 (75) | 5 (100) | 17 (68) |

| H558R, n (%) | 71 (28) | 0 (0) | 9 (36) | |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian, n (%) | 14 (4) | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Asian, n (%) | 93 (25) | 27 (11)* | 1 (20)4 | 4 (16) |

| African American, n (%) | 46 (12) | 37 (15) | 0 (0) | 9 (36)† |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 164 (43) | 147 (58)* | 2 (40)1,5 | 7 (28)† |

| Pacific Islander, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Multi-racial, n (%) | 33 (9) | 24 (9) | 1 (20)2 | 4 (16) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 26 (7) | 7 (3) | 1 (20)3 | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic, n (%) | 80 (21) | 40 (16) | 3 (60)2,3,5† | 4 (16) |

| Non-Hispanic, n (%) | 297 (79) | 212 (84) | 2 (40)1,4 | 21 (84) |

| IBS subtype | ||||

| IBS-C, n (%) | 75 (30) | 1 (20)2 | 8 (32) | |

| IBS-D, n (%) | 81 (32) | 3 (60)1,4,5 | 8 (32) | |

| IBS-M, n (%) | 65 (26) | 1 (20)3 | 5 (20) | |

| Other, n (%) | 31 (12) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; BMI, body mass index; IBS-C, IBS with constipation; IBS-D, IBS with diarrhea; IBS-M, mixed-subtype IBS. For race, P < 0.05, total IBS vs. control or SCN5A polymorphisms vs. total IBS (by χ2 test).

R225W;

R433C;

R986Q and S1700G heterozygote;

G1037V;

F1293S.

P < 0.05 vs. control and

P < 0.05 vs. total IBS (by Fisher’s exact test).

P < 0.05 vs. control (by nonparametric 2-tailed t-test).

We discovered 31 SCN5A variations in the IBS cohort. SCN5A polymorphisms, defined as having a MAF >0.1% (44), accounted for a majority at 25 of 31 (81%) SCN5A variations. The makeup of this cohort was similar to that of the IBS cohort. It was 68% (17 of 25) women and ethnically and racially diverse: Hispanic ethnicity (n = 4), Caucasian (n = 7), African American (n = 9), Asian (n = 4), American Indian (n = 1), and multi-racial (n = 4) (Table 2). This cohort differed from the IBS cohort, in that it comprised more (36%) African Americans and fewer (28%) Caucasians (P < 0.05 between IBS cohort and SCN5A polymorphisms, by Fisher’s exact test; Table 2).

We found six missense SCN5A mutations in 5 of the 252 patients (2.0%), as judged by a MAF <0.1% in the reference cohort (44) (Table 2). All five of the patients with SCN5A mutations were female (n = 5) and ethnically and racially diverse: Hispanic ethnicity (n = 3), Caucasian (n = 2), Asian (n = 1), and multi-racial (n = 1). None of these patients had a history of cardiac disease. We did not find any of these IBS-associated SCN5A mutations in IBS-negative control patients (n = 377).

Profile of the IBS-Related SCN5A Mutations

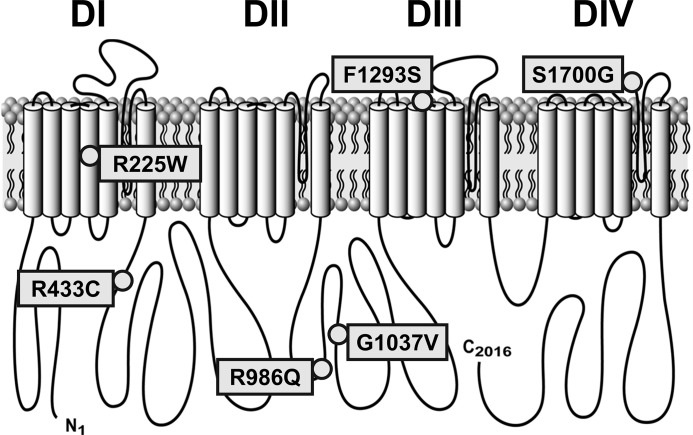

The IBS-associated SCN5A mutations were distributed across the protein (Fig. 1). One of these mutations (R225W) was in the transmembrane region, while the others were in linkers: intradomain [F1293S in domain IIIS3 (DIIIS3)-DIIIS4 and S1700G in DIVS5-DIVS6] or interdomain (R433C in DI-DII and R986Q and G1037V in DII-DIII). Three of the six (50%) mutations (R225W, R986Q, and F1293S) were previously identified in men to associate with cardiac disorders: wide complex tachycardia and dilated cardiomyopathy (R225W) (11), lone atrial fibrillation (R986Q) (18), and Brugada syndrome (F1293S) (39).

Fig. 1.

Topology of the voltage-gated mechanosensitive Na+ channel NaV1.5 with irritable bowel syndrome-associated mutations. DI, DII, DIII, and DIV domains I, II, III, and IV.

Functional Characterization of IBS-Related SCN5A Mutations

Previous studies found that SCN5A mutations that result in functional NaV1.5 abnormalities in vitro have pathophysiological implications in vivo (23). Therefore, we expressed all six of the identified SCN5A IBS-related mutations in HEK-293 cells and used our previously validated voltage-clamp protocols (8) to analyze the mutations for functional abnormalities.

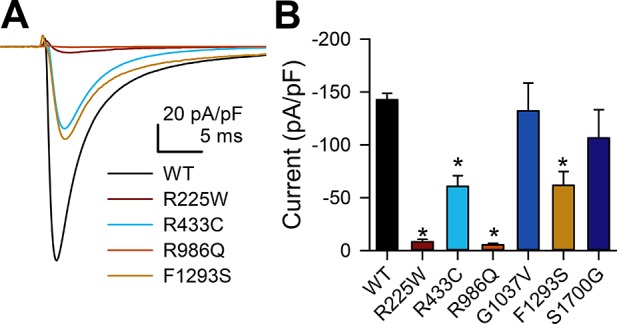

Peak Current Density

First, we examined peak current densities of all six identified NaV1.5 mutations (Fig. 2). Peak current density was decreased in four of six (67%) mutations, R225W (−8 ± 2 pA/pF), R433C (−61 ± 10 pA/pF), R986Q (−5 ± 1 pA/pF), and F1293S (−62 ± 13 pA/pF), compared with wild-type NaV1.5 (−143 ± 6 pA/pF, n = 8–11, P < 0.05 vs. WT; Fig. 2, Table 3). We consider the decrease in Na+ current a LOF, since Na+ influx depolarizes the cell membrane, bringing membrane voltage closer to activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, which are required for excitation-contraction coupling (8). Therefore, these four SCN5A mutations are LOF. None of the mutations resulted in a NaV1.5 channel with an increase in peak current [gain of function (GOF)].

Fig. 2.

NaV1.5 mutations R225W, R433C, R986Q, and F1293S have decreased current density. A: representative Na+ current traces elicited in wild-type (WT) or mutant NaV1.5-transfected HEK-293 cells by a step from −100 to −30 mV. B: current densities of the −30-mV current sweep of wild-type NaV1.5 vs. NaV1.5 mutations R225W, R433C, R986Q, G1037V, F1293S, and S1700G. Values are means ± SE; n = 8–12. *P < 0.05 vs. H558/Q1077del NaV1.5 (by nonparametric 2-tailed Student’s t-test).

Table 3.

Parameters of NaV1.5 in IBS patients with SCN5A missense mutations

| n | Ipeak, pA/pF | tpeak, ms | V1/2A, mV | δVA | V1/2I, mV | δVI | τIF, ms | τIS, ms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 11 | ||||||||

| No shear | −143 ± 6 | 1.35 ± 0.09 | −63.0 ± 1.3 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | −99.0 ± 2.3 | −5.7 ± 0.3 | 0.96 ± 0.07 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | |

| Shear | −169 ± 7* | 1.14 ± 0.07* | −63.7 ± 1.3* | 4.0 ± 0.2* | −100.4 ± 2.4 | −6.5 ± 0.5 | 0.64 ± 0.04* | 3.5 ± 0.2* | |

| R225W | 8 | ||||||||

| No shear | −8 ± 2† | 2.44 ± 0.12† | −45.5 ± 1.8† | 6.4 ± 0.3† | −89.8 ± 1.6† | −12.4 ± 2.6† | 1.67 ± 0.30† | 6.5 ± 1.6 | |

| Shear | −9 ± 2† | 2.11 ± 0.12*† | −47.9 ± 1.7*† | 6.4 ± 0.3† | −90.4 ± 1.3† | −12.2 ± 1.8† | 1.06 ± 0.22† | 4.1 ± 1.4 | |

| R433C | 9 | ||||||||

| No shear | −61 ± 10† | 1.73 ± 0.07† | −65.2 ± 2.2 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | −115.5 ± 3.0† | −4.0 ± 0.2† | 0.88 ± 0.07 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | |

| Shear | −78 ± 14*† | 1.48 ± 0.05*† | −68.2 ± 2.2* | 3.6 ± 0.2* | −118.9 ± 2.2*† | −3.7 ± 0.3† | 0.61 ± 0.03* | 2.9 ± 0.4* | |

| R986Q | 8 | ||||||||

| No shear | −5 ± 1† | 2.43 ± 0.27† | −43.3 ± 2.6† | 6.2 ± 0.4† | −84.8 ± 2.9† | −14.3 ± 2.0† | 1.89 ± 0.46† | 5.3 ± 0.7 | |

| Shear | −6 ± 2*† | 1.81 ± 0.14*† | −44.6 ± 2.2*† | 6.1 ± 0.3† | −85.9 ± 3.3† | −13.7 ± 2.8† | 1.37 ± 0.22† | 5.2 ± 0.9† | |

| G1037V | 12 | ||||||||

| No shear | −132 ± 26 | 1.55 ± 0.05† | −64.4 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | −109.3 ± 3.9† | −5.0 ± 0.3 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 4.0 ± 0.3† | |

| Shear | −157 ± 31* | 1.33 ± 0.05*† | −65.0 ± 1.0* | 4.0 ± 0.3* | −111.0 ± 4.9† | −4.6 ± 0.4† | 0.64 ± 0.05* | 2.9 ± 0.2*† | |

| F1293S | 8 | ||||||||

| No shear | −62 ± 13† | 1.93 ± 0.14† | −56.7 ± 1.9† | 3.9 ± 0.3 | −97.9 ± 1.7 | −5.1 ± 0.0 | 0.93 ± 0.09 | 6.5 ± 0.8† | |

| Shear | −68 ± 16† | 1.60 ± 0.12*† | −58.6 ± 1.9*† | 3.5 ± 0.3* | −99.6 ± 3.0 | −5.4 ± 0.3 | 0.69 ± 0.07* | 5.5 ± 0.9† | |

| S1700G | 9 | ||||||||

| No shear | −107 ± 27 | 1.49 ± 0.05 | −63.8 ± 0.9 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | −106.2 ± 2.5 | −4.9 ± 0.2 | 0.94 ± 0.10 | 3.9 ± 0.1† | |

| Shear | −127 ± 35* | 1.28 ± 0.05* | −64.6 ± 0.8* | 4.0 ± 0.2* | −107.4 ± 2.3 | −5.2 ± 0.0 | 0.60 ± 0.05* | 2.5 ± 0.2*† |

Values are means ± SE (n = 7–12). Shear stress, flow of extracellular solution; Ipeak, maximum peak current density; tpeak, time to peak current at −30 mV; V1/2A, voltage dependence of activation; δVA, slope of steady-state activation; V1/2I, voltage dependence of inactivation; δVI, slope of steady-state inactivation; τIF, time constant of fast inactivation at −30 mV; τIS, time constant of slow inactivation at −30 mV. Wild-type (WT) background was H558/Q1077del. Decreased current density, slower activation time constant, depolarized shift in V1/2 of activation, hyperpolarized shift in V1/2 of inactivation, or faster inactivation time constants compared with WT are shown in italic type (loss of function). Depolarized shift in V1/2 of inactivation or slower inactivation time constants compared with WT are underscored (gain of function).

P < 0.05 (boldface), shear vs. no shear (by 2-tailed paired Student’s t-test).

P < 0.05 (italic or underscored), missense mutation vs. WT (by 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test).

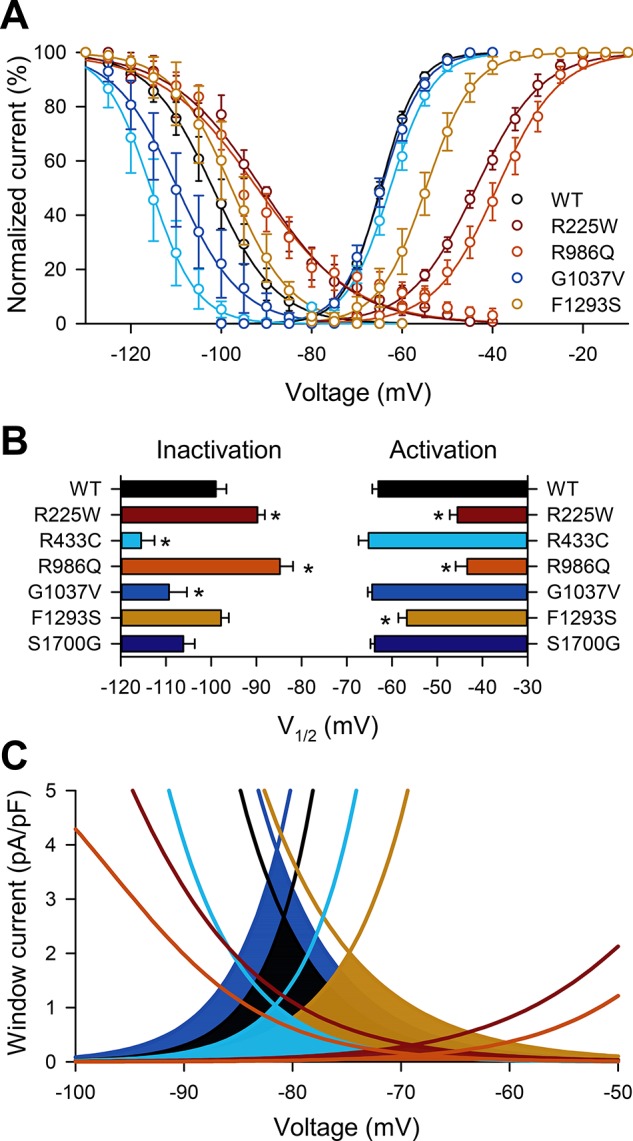

Voltage-Dependent Gating

We analyzed all NaV1.5 mutations for changes in steady-state voltage dependence (Fig. 3). Voltage dependence of activation (V1/2A) was shifted to more positive voltages in two of six (33%) mutations, R225W (−45.5 ± 1.8 mV) and R986Q (−43.3 ± 2.6 mV), compared with wild-type NaV1.5 (−63.0 ± 1.3 mV, n = 8–11, P < 0.05 vs. WT; Table 3). Voltage dependence of inactivation (V1/2I) was shifted to negative voltages in two of six (33%) mutations, R433C (−115.5 ± 3.0 mV) and G1037V (−109.3 ± 3.9 mV), and to positive voltages in two of six (33%) mutations, R225W (−89.8 ± 1.6 mV) and R986Q (−84.8 ± 2.9mV), compared with wild-type NaV1.5 (−99.0 ± 2.3 mV, n = 8–12, P < 0.05 vs. WT). An important property of NaV1.5 is the window current, which is defined as the area of overlap between the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation. When cell membrane voltage is within this window, a fraction of NaV1.5 channels are continuously open and, therefore, contribute to setting the membrane potential and overall electrical excitability. Three (50%) mutations (R225W, R433C, and R986Q) have a decreased window current, considered LOF for this property (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Voltage dependence of NaV1.5 mutations R225W, R433C, R986Q, and F1293S have shifts in steady-state voltage dependence that would lead to reduced window current. A: steady-state inactivation and activation curves of wild-type NaV1.5 or NaV1.5 mutations R225W, R433C, R986Q, and G1037V. B: average half-points of voltage dependence of inactivation or activation of mutations in A, as well as F1293S and S1700G. V1/2, voltage of half-activation. Values are means ± SE; n = 8–12. *P < 0.05 vs. H558/Q1077del NaV1.5 (by nonparametric 2-tailed Student’s t-test). C: projected window currents of mutations with shifts in voltage dependence as shown in B.

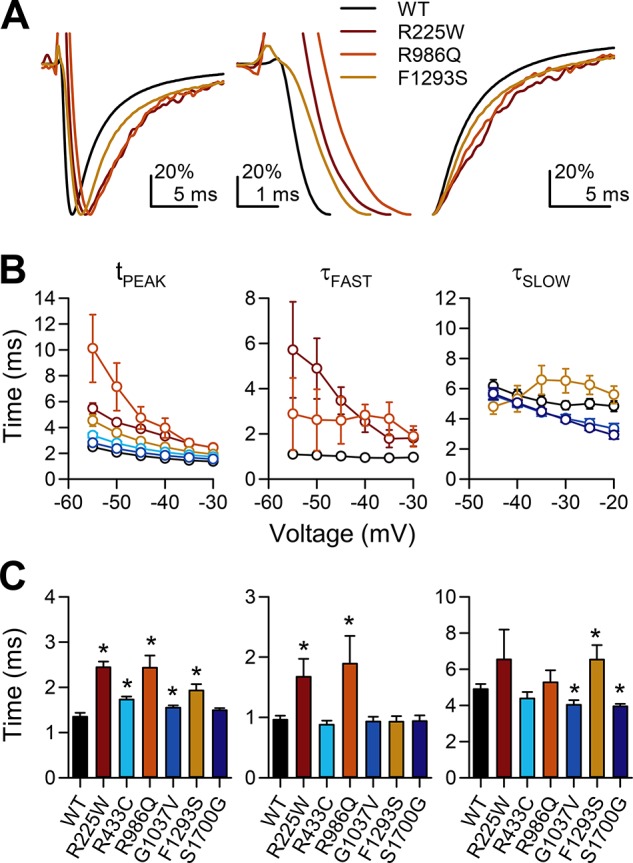

Activation and Inactivation kinetics

Next, we looked for changes in activation and inactivation kinetics (Fig. 4). These are important parameters when considering GOF and LOF, given that, along with peak current, they reflect a total amount of charge carried across the cell membrane. Therefore, slowing of the activation time represents LOF. We found that the times to peak current for five of the six (87%) mutations were slower than for wild-type NaV1.5 (1.35 ± 0.09 ms, n = 8–12, P < 0.05): R225W (2.44 ± 0.12 ms), R433C (1.73 ± 0.07 ms), R986Q (2.43 ± 0.27 ms), G1037V (1.55 ± 0.05 ms), and F1293S (1.93 ± 0.14 ms). Acceleration of the inactivation time constants represents LOF. We found faster inactivation in two of the six (33%) mutations than in wild-type NaV1.5 [slow time constant of inactivation (τIS), 4.9 ± 0.3 ms, n = 8–12, P < 0.05 vs. WT): G1037V (4.0 ± 0.3 ms) and S1700G (3.9 ± 0.1 ms). Deceleration of the time constants results in an increase in total charge carried during stimulation, reflecting a GOF. We found slower inactivation in two of the six (33%) mutations compared with WT NaV1.5 [fast time constant of inactivation (τIF), 0.96 ± 0.07 ms, n = 8–11, P < 0.05 vs. WT): R225W (1.67 ± 0.30 ms) and R986Q (1.89 ± 0.46 ms) (Fig. 4, Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Activation and inactivation kinetics are slower in NaV1.5 mutations R225W, R986Q, and F1293S, while inactivation kinetics are faster in G1037V and S1700G. A: representative current traces of wild-type and mutant NaV1.5 R225W, R986Q, and F1293S, elicited by a step from −100 to −30 mV and normalized by scaling from 0 pA to peak. Traces are shown elapsed over 30 ms (left), up to peak current (middle), or from peak current (right). B: average time to peak (tpeak) and fast and slow time constants of inactivation (τfast and τslow) of wild-type NaV1.5 (black) or NaV1.5 mutations R225W (red), R433C (light blue), R986Q (orange), G1037V (blue), F1293S (yellow), and S1700G (dark blue). C: averages of all mutations screened at the −30-mV test pulse. Values are means ± SE; n = 8–12. *P < 0.05 vs. H558/Q1077del NaV1.5 (by nonparametric 2-tailed Student’s t-test).

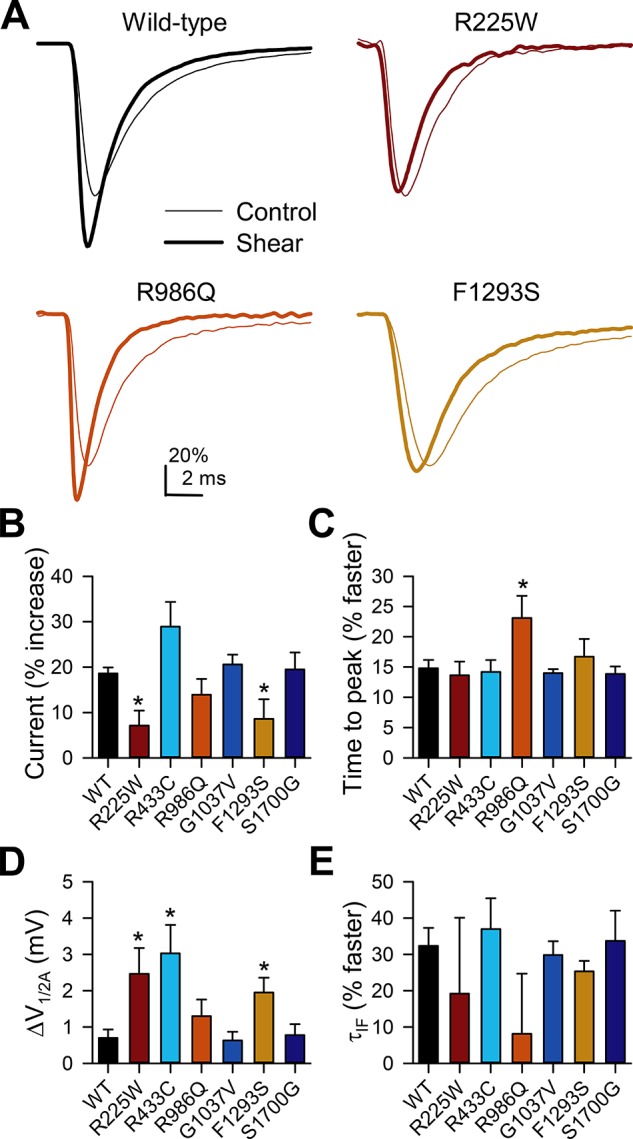

Mechanosensitivity

NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity plays a key role in GI physiology (35), and loss of NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity is associated with IBS (37). Therefore, it was important to determine whether any of the discovered IBS mutations lead to alterations in NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity. When examined under shear stress, mechanical forces have several effects on wild-type NaV1.5. Most notably, they increase peak current by 19 ± 1% [peak current density (ΔIpeak) −143 ± 6 pA/pF (control) to −169 ± 7 pA/pF (shear)], shift the voltage dependence of activation to the left by −0.7 ± 0.2 mV [voltage of half-activation (ΔV1/2A) −63.0 ± 1.3 mV (control) to −63.7 ± 1.3 mV (shear)], accelerate the kinetics of activation by 15 ± 1% [time to peak (Δtpeak) 1.35 ± 0.09 ms (control) to 1.14 ± 0.07 ms (shear)] and inactivation [fast time constant of inactivation (ΔτIF) 32 ± 5% faster: 0.96 ± 0.07 ms (control) to 0.64 ± 0.04 ms (shear); slow time constant of inactivation (ΔτIS) 27 ± 3% faster: 4.9 ± 0.3 ms (control) to 3.5 ± 0.2 ms (shear), n = 11, all stated parameters are P < 0.05, shear vs. control] (Fig. 5, Tables 3 and 4).

Fig. 5.

Peak currents of NaV1.5 mutations R225W and F1293S have reduced shear sensitivity, whereas activation and inactivation kinetics of R986Q have increased shear sensitivity. A: representative current traces elicited by a step from −100 to −30 mV in HEK-293 cells transfected with wild-type NaV1.5 or NaV1.5 mutations R225W, R986Q, and F1293S before (control) or during (shear) flow of extracellular solution at a rate of 10 ml/min. B: peak inward Na+ currents during shear, expressed as percent increase over control currents. C: time to peak of inward Na+ currents during shear, expressed as percent decrease in time to peak of control currents. D: change in half-point of voltage dependence of activation (V1/2A) with shear. E: time constant of inactivation (τIF) of inward Na+ currents during shear, expressed as percent decrease in inactivation time of control currents. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. H558/Q1077del NaV1.5 (by nonparametric 2-tailed Student’s t-test).

Table 4.

Parameters of NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity in IBS patients with SCN5A missense mutations

| ΔIpeak, %increase | Δtpeak, %faster | ΔV1/2A, mV | ΔτIF, %faster | ΔτIS, %faster | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 19 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | −0.7 ± 0.2 | 32 ± 5 | 27 ± 3 |

| R225W | 7 ± 3* | 14 ± 2 | −2.5 ± 0.7* | 19 ± 21 | 40 ± 23 |

| R433C | 29 ± 5 | 14 ± 2 | −3.0 ± 0.8* | 37 ± 8 | 35 ± 8 |

| R986Q | 14 ± 3 | 23 ± 4* | −1.3 ± 0.5 | 8 ± 17 | −4 ± 19 |

| G1037V | 21 ± 2 | 14 ± 1 | −0.6 ± 0.2 | 30 ± 4 | 29 ± 2 |

| F1293S | 9 ± 4* | 17 ± 3 | −1.9 ± 0.4* | 25 ± 3 | 17 ± 8 |

| S1700G | 19 ± 4 | 14 ± 1 | −0.8 ± 0.3 | 34 ± 8 | 37 ± 4 |

Values are means ± SE (n = 7–12, as in Table 1). ΔIpeak, %increase in maximum peak current density; Δtpeak, %decrease in time to peak current at −30 mV; ΔV1/2A, shift in voltage dependence of activation; ΔτIF, %decrease in time constant of fast inactivation at −30 mV; ΔτIS, %decrease in time constant of slow inactivation at −30 mV. Wild-type (WT) background was H558/Q1077del. Decreased change in current density compared with WT is shown in italic type (loss of function). Increased change in time to peak or decreased change in time constant of inactivation compared with WT is underscored (gain of function).

P < 0.05 (italic or underscored), missense mutation vs. WT (by 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test).

Then, using our validated shear-stress voltage-clamp protocols, we examined all the discovered mutants for changes in mechanosensitivity (Fig. 5, Table 4) (37). We found alterations in at least one functional parameter for four of six (67%) IBS-associated SCN5A mutations. Shear sensitivity of peak current was decreased, constituting a LOF in two of six (33%) mutations, R225W [from −8 ± 2 pA/pF (control) to −9 ± 2 pA/pF (shear), n = 8, P > 0.05, control vs. shear; ΔIpeak 7 ± 3% increase, P < 0.05 vs. WT NaV1.5] and F1293S [from −62 ± 13 pA/pF (control) to −68 ± 16 pA/pF (shear), n = 8, P > 0.05, control vs. shear; ΔIpeak 9 ± 4% increase, P < 0.05 vs. WT NaV1.5]. Negative shifts in V1/2A in response to shear increased in three of six (50%) mutations: R225W [from −45.5 ± 1.8 mV (control) to −47.9 ± 1.7 mV (shear), n = 11, P < 0.05, control vs. shear; ΔV1/2A −2.5 ± 0.7 mV, P < 0.05 vs. WT NaV1.5], R433C [from −43.3 ± 2.6 mV (control) to −44.6 ± 2.2 mV (shear), n = 14, P < 0.05, control vs. shear; ΔV1/2A −3.0 ± 0.8 mV, P < 0.05 vs. WT NaV1.5], and F1293S [from −56.7 ± 1.9 mV (control) to −58.6 ± 1.9 mV (shear), n = 11, P < 0.05, control vs. shear; ΔV1/2A −1.9 ± 0.4 mV, P < 0.05 vs. WT NaV1.5]. Shear sensitivity of the kinetics of activation was increased for one of six (17%) mutations: R986Q [from 2.43 ms (control) to 1.81 ms (shear), n = 8, P < 0.05, control vs. shear; Δtpeak 23 ± 4% faster, P < 0.05 vs. WT NaV1.5] (Fig. 5, Tables 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

Advances in sequencing have shined a light on ion channelopathies, which are diseases due to mutations in pore-forming or associating ion channel proteins that result in abnormal ion channel function (5). Previous studies revealed that patients with SCN5A mutations have an increase in IBS prevalence (25) and that between 2.0% (37) and 2.2% (8) of IBS patients have rare SCN5A mutations, the majority of which are responsible for NaV1.5 ion channelopathies (8, 37).

SCN5A Mutations Are Present in 2% of IBS Patients

In this study we used a geographically distinct, racially and ethnically diverse IBS patient cohort (Table 2) to confirm and extend the findings from the predominantly Caucasian Olmsted County cohorts (8, 25, 37). In this cohort, we found that 2.0% (5 of 252) of the patients had SCN5A mutations, and one patient had two rare SCN5A mutations (Fig. 4). This frequency closely matched previously reported frequencies of 2.0–2.2% of SCN5A channelopathies in IBS patients (8, 37).Importantly, in this study we did not find these mutations in a large cohort of IBS-negative control patients (n = 377), which further strengthens the connection between SCN5A mutations and IBS.

The IBS-associated SCN5A mutations were distributed across the SCN5A topology, in the transmembrane region and extracellular and intracellular linkers (Fig. 1). Previous work on SCN5A channelopathies in cardiac conduction disorders showed that pathogenicity is not evenly distributed across the SCN5A topology: transmembrane and extracellular regions are most significant [3 of 6 (50%) for this cohort], while intracellular linkers are generally less significant [3 of 6 (50%) for this cohort] (23). Considering previously available data on IBS-related SCN5A mutations, 15% (n = 3) are extracellular, 15% (n = 3) are transmembrane, and 70% (n = 14) are intracellular; of the intracellular mutations, 7% are on the NH2 terminus, 64% (n = 9) are on interdomain linkers, and 29% (n = 4) are on the COOH terminus. However, the major caveat to viewing pathogenicity from the standpoint of cardiac conduction disorders is that the mechanism of IBS pathogenesis due to SCN5A mutations is likely different from that of cardiac conduction disorders (8, 35, 37); therefore, it remains unclear which SCN5A regions are more pathogenic for IBS. Similar to the current work, studies on IBS-associated SCN5A channelopathies are needed to compare well-defined cohorts of IBS patients and IBS-negative controls (15, 19), to increase the number of SCN5A mutations in IBS patients, and to determine which SCN5A regions are most relevant for IBS.

IBS-Associated SCN5A Mutations Result in NaV1.5 Channels With Abnormal Voltage-Dependent and Mechanosensitive Functions

Previous studies showed that the majority of IBS-linked SCN5A mutations are functionally abnormal and that the majority of IBS-associated mutations are LOF (8, 37). To determine the functional significance of these IBS-linked SCN5A mutations, we used the voltage-clamp protocol to examine all six of the discovered IBS-linked SCN5A mutations for abnormalities in NaV1.5 voltage-dependent and mechanosensitive function. We found a variety of abnormalities in voltage-dependent function in all mutations. All 6 (100%) mutations had a functional change in ≥1 parameter that was consistent with LOF, and for all mutations LOF parameters accounted for 20 of 26 (77%) functionally abnormal parameters, while GOF accounted for 6 of 26 (23%) parameters (Table 3). Therefore, the current study in a racially and ethnically diverse cohort is consistent with the previous studies in Caucasian cohorts that showed that 77–100% of IBS-associated mutations are functionally abnormal and that a majority, but not all, of them are LOF (8, 37).

In a previous pilot study, a patient with IBS had a SCN5A mutation G298S that resulted in NaV1.5 channels with abnormal mechanosensitivity (37). Given the importance of NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity for GI motility (35), we examined all the mutations discovered in this study for abnormalities in mechanosensitivity. We found that four of six (67%) mutations had abnormal mechanosensitivity. Two of six (33%) mutations (R225W and F1293S) had a significant loss in mechanosensitivity (Fig. 5). Interestingly, voltage-dependent LOF did not predict mechanosensitive LOF, since R433C and R986Q had significant peak-current LOF but normal mechanosensitivity, as measured by an increase in peak current in response to shear stress (Fig. 5). In fact, for voltage-dependent LOF mutants R225W, R433C, and F1293S, we found that shear increased a leftward shift in the voltage dependence of activation, which would signify mechanosensitive GOF. Therefore, our data show that IBS-associated SCN5A mutations result in NaV1.5 channels with abnormal mechanosensitivity in ~67% of the cases, but alterations in NaV1.5 voltage-dependent function and mechanosensitivity are not necessarily linked. The mechanism of NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity is poorly understood (9, 32), and these patient-derived mutations may be useful for elucidation of basic mechanisms of NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity, as they have been for long QT syndrome in the heart (2). Abnormalities in NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity could still be discovered in disease-associated NaV1.5 mutations that lack an in vitro phenotype (36).

IBS-Associated SCN5A Mutations Are Present in Patients With Cardiac Conduction Disorders

In addition to an IBS phenotype, previous studies have linked SCN5A channelopathies to cardiac conduction disorders, such as long QT type 3 (1) and Brugada syndrome (24), where SCN5A plays a critical role. SCN5A mutations are also linked to atrial fibrillation (16) and dilated cardiomyopathy (29) by less clear mechanisms. Three of the six (50%) mutations we identified in our IBS cohort (R225W, R986Q, and F1293S) were previously linked to cardiac phenotypes, again suggesting that the IBS-associated SCN5A mutations are likely pathogenic (11, 18, 39). These three mutations were previously examined for abnormalities in the voltage-dependent function in transfected cell systems like ours.

Similar to our findings, when transfected in HEK-293 cells and compared with wild-type NaV1.5, the NaV1.5 mutation R225W caused a ~90% reduction in peak current density, rightward shifts in the half-points of voltage dependence of activation and inactivation, and significantly shallower slopes of voltage dependence of activation and inactivation (11). These abnormalities might have been caused by a gating charge loss due to the arginine-to-tryptophan mutation in the domain I voltage sensor. Also interesting is that R225W NaV1.5 has an accentuated ω-current (31), an ionic current through the voltage-sensor region of the channel (40). The ω-current may alter excitability independent of the decrease in current through the ion channel pore, as was proposed for cardiac conduction disorder patients with R225W NaV1.5 (30, 31). We speculate that this ω-current may be responsible for the diarrhea-predominant IBS phenotype in the patient with R225W NaV1.5 in this study.

A previous study links R986Q to a male patient with lone atrial fibrillation (18). When expressed in CHO-K1 cells, R986Q had significantly reduced the peak Na+ current density ~50%, which is similar to our findings (Fig. 2). However, unlike our study, the authors did not find significant differences in steady-state voltage-dependence parameters (V1/2A, V1/2I, δVA, and δVI), but this was due to wild-type differences between the two studies (18). In a different report, F1293S NaV1.5 was found in a 3-yr-old boy with a compound heterozygote phenotype (p.F1293S and c.3258–3261del4) and Brugada syndrome (39). The authors compared some voltage-dependence properties of F1293S NaV1.5 with wild-type and, similar to our findings, discovered ~40% loss of peak current, which is similar to our findings of ~60% loss of peak current. In all, previous studies have identified three of these six IBS-associated mutations in patients with cardiac conduction disorders, and in vitro analysis of these mutations discovered voltage-dependent function alterations that are consistent with the abnormalities discovered in this study.

Sex-Dependent Manifestation of SCN5A Channelopathies in Heart and Gut

All five (100%) of the patients with SCN5A mutations in our IBS cohort were female, compared with 75% female patients in the overall cohort. Similarly, in our previous studies, 85% (8) and 100% (37) of the IBS patients with pathogenic SCN5A mutations were female. None of the female patients with IBS-associated SCN5A mutations had ECG or cardiac conduction abnormalities. Therefore, while naturally occurring SCN5A variants are evenly distributed in male and female patients, of the currently known IBS-related SCN5A mutations, 90% (17 of 19) were discovered in female patients. It is well known that IBS is more prevalent in female than male patients, but by a smaller margin than we find for the female predominance of IBS-related SCN5A mutations (26). Interestingly, Brugada syndrome, a cardiac conduction disorder associated with SCN5A LOF, is severalfold more likely to be phenotypically significant in male patients with SCN5A mutations (4). In the heart, this sex difference has been linked to sex hormones (28, 38) and appears to depend on differences in the transient outward K+ current (Ito) between men and women (17). In this study, all IBS-associated SCN5A mutations were found in women, but three of these six IBS-associated SCN5A mutations were previously identified in men with cardiac arrhythmias. Consistent with this sex discrepancy of the GI vs. cardiac phenotype, a previous study reported that a male patient with R225W inherited this mutation from his mother (he was compound heterozygote W156X and R225W) and had severe wide-complex tachycardia and dilated cardiomyopathy, while his mother had neither the conduction disorder nor dilated cardiomyopathy (11). Sex hormones are known to affect GI smooth muscle electrophysiology: there are differences in inward currents with application of progesterone (12). However, whether there is a difference between men and women in terms of K+ current density, another balancing current, or inward currents in GI smooth muscle is unknown.

Study Limitations

First, we used HEK-293 cells for expression of the SCN5A constructs, since these cells provide a validated robust platform for ion channel expression with low endogenous ion channel expression. Future studies are needed to examine IBS-associated SCN5A channelopathies in smooth muscle cells. Second, we have taken a conservative approach to define mutations as being only when the SCN5A MAF was <0.1% according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project. Given that the prevalence of IBS is high in the general population and that control groups in cardiac-related studies did not exclude IBS, it is likely that we underestimated the prevalence of IBS-associated SCN5A mutations. Third, in terms of sample size, we have determined a prevalence of 2% for SCN5A channelopathies in IBS in this large cohort, which matches that found in previous studies. However, a larger sample size is required to discover enough IBS-associated SCN5A mutations to draw full mechanistic conclusions, including changes in physiology. For example, this study and others have shown IBS-associated SCN5A mutations predominantly in women, while previous studies have clearly shown that cardiac disease-associated SCN5A mutations are more common in men. However, to draw a more definitive association, larger studies should obtain SCN5A genotyping along with detailed GI and cardiovascular family histories, including GI and cardiac physiological measurements such as GI transit and ECGs.

In summary, this study of a racially and ethnically diverse IBS cohort confirms previous reports that 2–3% of IBS patients have SCN5A-encoded NaV1.5 channelopathies, the majority of which have abnormal voltage-dependent function and mechanosensitivity in vitro.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grants DK-52766 (G. Farrugia), DK- 66271 (Y. A. Saito), and DK-106456 (A. Beyder), an American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award (A. Beyder), the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (NIDDK Grant P30 DK-084567), and the Mayo Clinic Windland Smith Rice Comprehensive Sudden Cardiac Death Program.

DISCLOSURES

M. J. Ackerman serves as a consultant to Boston Scientific, Gilead Sciences, Invitae, Medtronic, MyoKardia, and St. Jude Medical and receives royalties from Transgenomic.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.R.S., L.C., A.B., and G.F. conceived and designed research; P.R.S., A.M., C.E.B., L.N., D.J.T., M.L.C., and L.C. performed experiments; P.R.S., A.M., D.J.T., M.L.C., and L.C. analyzed data; P.R.S., A.M., D.J.T., M.L.C., L.C., A.B., and G.F. interpreted results of experiments; P.R.S. prepared figures; P.R.S. drafted manuscript; P.R.S., A.M., L.N., S.J.G., Y.A.S., E.A.M., L.C., M.J.A., A.B., and G.F. edited and revised manuscript; P.R.S., A.M., C.E.B., L.N., S.J.G., Y.A.S., D.J.T., M.L.C., E.A.M., L.C., M.J.A., A.B., and G.F. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Zodrow for administrative assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackerman MJ. The long QT syndrome: ion channel diseases of the heart. Mayo Clin Proc 73: 250–269, 1998. doi: 10.4065/73.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banderali U, Juranka PF, Clark RB, Giles WR, Morris CE. Impaired stretch modulation in potentially lethal cardiac sodium channel mutants. Channels (Austin) 4: 12–21, 2010. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.1.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barajas-López C, Den Hertog A, Huizinga JD. Ionic basis of pacemaker generation in dog colonic smooth muscle. J Physiol 416: 385–402, 1989. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benito B, Sarkozy A, Mont L, Henkens S, Berruezo A, Tamborero D, Arzamendi D, Berne P, Brugada R, Brugada P, Brugada J. Gender differences in clinical manifestations of Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 52: 1567–1573, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyder A, Farrugia G. Ion channelopathies in functional GI disorders. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 311: G581–G586, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00237.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beyder A, Farrugia G. Targeting ion channels for the treatment of gastrointestinal motility disorders. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 5: 5–21, 2012. doi: 10.1177/1756283X11415892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyder A, Gibbons SJ, Mazzone A, Strege PR, Saravanaperumal SA, Sha L, Higgins S, Eisenman ST, Bernard CE, Geurts A, Kline CF, Mohler PJ, Farrugia G. Expression and function of the Scn5a-encoded voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.5 in the rat jejunum. Neurogastroenterol Motil 28: 64–73, 2016. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beyder A, Mazzone A, Strege PR, Tester DJ, Saito YA, Bernard CE, Enders FT, Ek WE, Schmidt PT, Dlugosz A, Lindberg G, Karling P, Ohlsson B, Gazouli M, Nardone G, Cuomo R, Usai-Satta P, Galeazzi F, Neri M, Portincasa P, Bellini M, Barbara G, Camilleri M, Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, D’Amato M, Ackerman MJ, Farrugia G. Loss-of-function of the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.5 (channelopathies) in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 146: 1659–1668, 2014. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyder A, Rae JL, Bernard C, Strege PR, Sachs F, Farrugia G. Mechanosensitivity of NaV1.5, a voltage-sensitive sodium channel. J Physiol 588: 4969–4985, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.199034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyder A, Strege PR, Reyes S, Bernard CE, Terzic A, Makielski J, Ackerman MJ, Farrugia G. Ranolazine decreases mechanosensitivity of the voltage-gated sodium ion channel NaV1.5: a novel mechanism of drug action. Circulation 125: 2698–2706, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.094714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bezzina CR, Rook MB, Groenewegen WA, Herfst LJ, van der Wal AC, Lam J, Jongsma HJ, Wilde AA, Mannens MM. Compound heterozygosity for mutations (W156X and R225W) in SCN5A associated with severe cardiac conduction disturbances and degenerative changes in the conduction system. Circ Res 92: 159–168, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000052672.97759.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bielefeldt K, Waite L, Abboud FM, Conklin JL. Nongenomic effects of progesterone on human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 271: G370–G376, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cattaruzza F, Spreadbury I, Miranda-Morales M, Grady EF, Vanner S, Bunnett NW. Transient receptor potential ankyrin-1 has a major role in mediating visceral pain in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298: G81–G91, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00221.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor JA, Prosser CL, Weems WA. A study of pace-maker activity in intestinal smooth muscle. J Physiol 240: 671–701, 1974. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Amato M. Genes and functional GI disorders: from casual to causal relationship. Neurogastroenterol Motil 25: 638–649, 2013. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darbar D, Kannankeril PJ, Donahue BS, Kucera G, Stubblefield T, Haines JL, George AL Jr, Roden DM. Cardiac sodium channel (SCN5A) variants associated with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 117: 1927–1935, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.757955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Diego JM, Cordeiro JM, Goodrow RJ, Fish JM, Zygmunt AC, Pérez GJ, Scornik FS, Antzelevitch C. Ionic and cellular basis for the predominance of the Brugada syndrome phenotype in males. Circulation 106: 2004–2011, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000032002.22105.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi K, Konno T, Tada H, Tani S, Liu L, Fujino N, Nohara A, Hodatsu A, Tsuda T, Tanaka Y, Kawashiri MA, Ino H, Makita N, Yamagishi M. Functional characterization of rare variants implicated in susceptibility to lone atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 8: 1095–1104, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henström M, Hadizadeh F, Beyder A, Bonfiglio F, Zheng T, Assadi G, Rafter J, Bujanda L, Agreus L, Andreasson A, Dlugosz A, Lindberg G, Schmidt PT, Karling P, Ohlsson B, Talley NJ, Simren M, Walter S, Wouters M, Farrugia G, D’Amato M. TRPM8 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of IBS-C and IBS-M. Gut 66: 1725–1727, 2017. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holland PM, Abramson RD, Watson R, Gelfand DH. Detection of specific polymerase chain reaction product by utilizing the 5′–3′ exonuclease activity of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 7276–7280, 1991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holm AN, Rich A, Miller SM, Strege P, Ou Y, Gibbons S, Sarr MG, Szurszewski JH, Rae JL, Farrugia G. Sodium current in human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology 122: 178–187, 2002. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Job DD. Ionic basis of intestinal electrical activity. Am J Physiol 217: 1534–1541, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapa S, Tester DJ, Salisbury BA, Harris-Kerr C, Pungliya MS, Alders M, Wilde AA, Ackerman MJ. Genetic testing for long-QT syndrome: distinguishing pathogenic mutations from benign variants. Circulation 120: 1752–1760, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Alders M, Benito B, Berthet M, Brugada J, Brugada P, Fressart V, Guerchicoff A, Harris-Kerr C, Kamakura S, Kyndt F, Koopmann TT, Miyamoto Y, Pfeiffer R, Pollevick GD, Probst V, Zumhagen S, Vatta M, Towbin JA, Shimizu W, Schulze-Bahr E, Antzelevitch C, Salisbury BA, Guicheney P, Wilde AA, Brugada R, Schott JJ, Ackerman MJ. An international compendium of mutations in the SCN5A-encoded cardiac sodium channel in patients referred for Brugada syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm 7: 33–46, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locke GR 3rd, Ackerman MJ, Zinsmeister AR, Thapa P, Farrugia G. Gastrointestinal symptoms in families of patients with an SCN5A-encoded cardiac channelopathy: evidence of an intestinal channelopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 1299–1304, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 712–721.e714, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makielski JC, Ye B, Valdivia CR, Pagel MD, Pu J, Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. A ubiquitous splice variant and a common polymorphism affect heterologous expression of recombinant human SCN5A heart sodium channels. Circ Res 93: 821–828, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000096652.14509.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuo K, Akahoshi M, Seto S, Yano K. Disappearance of the Brugada-type electrocardiogram after surgical castration: a role for testosterone and an explanation for the male preponderance. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 26, 7p1: 1551–1553, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.t01-1-00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNair WP, Sinagra G, Taylor MR, Di Lenarda A, Ferguson DA, Salcedo EE, Slavov D, Zhu X, Caldwell JH, Mestroni L; Familial Cardiomyopathy Registry Research Group . SCN5A mutations associate with arrhythmic dilated cardiomyopathy and commonly localize to the voltage-sensing mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 2160–2168, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreau A, Gosselin-Badaroudine P, Chahine M. Molecular biology and biophysical properties of ion channel gating pores. Q Rev Biophys 47: 364–388, 2014. doi: 10.1017/S0033583514000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreau A, Gosselin-Badaroudine P, Delemotte L, Klein ML, Chahine M. Gating pore currents are defects in common with two NaV1.5 mutations in patients with mixed arrhythmias and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Gen Physiol 145: 93–106, 2015. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201411304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris CE, Juranka PF. NaV channel mechanosensitivity: activation and inactivation accelerate reversibly with stretch. Biophys J 93: 822–833, 2007. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muraki K, Imaizumi Y, Watanabe M. Sodium currents in smooth muscle cells freshly isolated from stomach fundus of the rat and ureter of the guinea-pig. J Physiol 442: 351–375, 1991. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nash DT, Nash SD. Ranolazine for chronic stable angina. Lancet 372: 1335–1341, 2008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neshatian L, Strege PR, Rhee P-L, Kraichely RE, Mazzone A, Bernard CE, Cima RR, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Kline CF, Mohler PJ, Beyder A, Farrugia G. Ranolazine inhibits voltage-gated mechanosensitive sodium channels in human colon circular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 309: G506–G512, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00051.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruan Y, Liu N, Priori SG. Sodium channel mutations and arrhythmias. Nat Rev Cardiol 6: 337–348, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito YA, Strege PR, Tester DJ, Locke GR III, Talley NJ, Bernard CE, Rae JL, Makielski JC, Ackerman MJ, Farrugia G. Sodium channel mutation in irritable bowel syndrome: evidence for an ion channelopathy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 296: G211–G218, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90571.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimizu W, Matsuo K, Kokubo Y, Satomi K, Kurita T, Noda T, Nagaya N, Suyama K, Aihara N, Kamakura S, Inamoto N, Akahoshi M, Tomoike H. Sex hormone and gender difference—role of testosterone on male predominance in Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 18: 415–421, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sommariva E, Vatta M, Xi Y, Sala S, Ai T, Cheng J, Pappone C, Ferrari M, Benedetti S. Compound heterozygous SCN5A gene mutations in asymptomatic Brugada syndrome child. Cardiogenetics 2: 53–58, 2012. doi: 10.4081/cardiogenetics.2012.e11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Starace DM, Stefani E, Bezanilla F. Voltage-dependent proton transport by the voltage sensor of the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron 19: 1319–1327, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strege PR, Holm AN, Rich A, Miller SM, Ou Y, Sarr MG, Farrugia G. Cytoskeletal modulation of sodium current in human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C60–C66, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00532.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strege PR, Mazzone A, Kraichely RE, Sha L, Holm AN, Ou Y, Lim I, Gibbons SJ, Sarr MG, Farrugia G. Species dependent expression of intestinal smooth muscle mechanosensitive sodium channels. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19: 135–143, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strege PR, Ou Y, Sha L, Rich A, Gibbons SJ, Szurszewski JH, Sarr MG, Farrugia G. Sodium current in human intestinal interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G1111–G1121, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00152.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong GK, Yang Z, Passey DA, Kibukawa M, Paddock M, Liu CR, Bolund L, Yu J. A population threshold for functional polymorphisms. Genome Res 13: 1873–1879, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiong Z, Sperelakis N, Noffsinger A, Fenoglio-Preiser C. Fast Na+ current in circular smooth muscle cells of the large intestine. Pflugers Arch 423: 485–491, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF00374945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]