Abstract

The left ventricular working, crystalloid-perfused heart is used extensively to evaluate basic cardiac function, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Crystalloid-perfused hearts may be limited by oxygen delivery, as adding oxygen carriers increases myoglobin oxygenation and improves myocardial function. However, whether decreased myoglobin oxygen saturation impacts oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) is unresolved, since myoglobin has a much lower affinity for oxygen than cytochrome c oxidase (COX). In the present study, a laboratory-based synthesis of an affordable perfluorocarbon (PFC) emulsion was developed to increase perfusate oxygen carrying capacity without impeding optical absorbance assessments. In left ventricular working hearts, along with conventional measurements of cardiac function and metabolic rate, myoglobin oxygenation and cytochrome redox state were monitored using a novel transmural illumination approach. Hearts were perfused with Krebs-Henseleit (KH) or KH supplemented with PFC, increasing perfusate oxygen carrying capacity by 3.6-fold. In KH-perfused hearts, myoglobin was deoxygenated, consistent with cytoplasmic hypoxia, and the mitochondrial cytochromes, including COX, exhibited a high reduction state, consistent with OxPhos hypoxia. PFC perfusate increased aortic output from 76 ± 6 to 142 ± 4 ml/min and increased oxygen consumption while also increasing myoglobin oxygenation and oxidizing the mitochondrial cytochromes. These results are consistent with limited delivery of oxygen to OxPhos resulting in an adapted lower cardiac performance with KH. Consistent with this, PFCs increased myocardial oxygenation, and cardiac work was higher over a wider range of perfusate Po2. In summary, heart mitochondria are limited by oxygen delivery with KH; supplementation of KH with PFC reverses mitochondrial hypoxia and improves cardiac performance, creating a more physiological tissue oxygen delivery.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Optical absorbance spectroscopy of intrinsic chromophores reveals that the commonly used crystalloid-perfused working heart is oxygen limited for oxidative phosphorylation and associated cardiac work. Oxygen-carrying perfluorocarbons increase myocardial oxygen delivery and improve cardiac function, providing a more physiological mitochondrial redox state and emphasizing cardiac work is modulated by myocardial oxygen delivery.

Keywords: cytochrome c oxidase, myoglobin oxygen saturation, oxidative phosphorylation, rabbit, rapid-scanning optical spectroscopy

INTRODUCTION

The isolated, perfused, left ventricular (LV) working heart is used extensively to investigate cardiac function and metabolism. These preparations allow substrate, metabolite, and hormone concentrations to be controlled as well as pH, preload and afterload pressures, and perfusate Po2 and Pco2. The LV working heart preparation is valuable because physiological workloads are reproduced and intrinsic physiological control of coronary flow (CF) is present, recapitulating essential elements of in vivo control.

Oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) is the primary source of myocardial energy (25). For an ex vivo perfused heart to appropriately represent in vivo function, adequate oxygenation to support aerobic metabolism must be maintained. Crystalloid perfusates, the most popular of which are Krebs-Henseleit (KH) and Tyrode saline-based solutions, are typically used in perfused heart experiments. These crystalloid perfusates have much lower oxygen carrying capacities than blood, and crystalloid-perfused hearts compensate, to some extent, with higher CFs (7, 12, 16, 32). Furthermore, previous studies have indicated that hearts perfused with crystalloid perfusate have compromised function and impaired cellular oxygenation (11, 12, 16, 32, 34, 36). Heart performance is improved when the perfusate oxygen carrying capacity is increased by the addition of red blood cells (RBCs) or artificial oxygen carriers (7, 11, 12, 16, 21, 27, 28, 32, 34, 37). The addition of RBCs to the perfusate has been shown to enhance myoglobin (Mb) oxygenation, reflecting an increase in cytosolic oxygen tension (34); however, no information is available regarding the oxidation-reduction (redox) status of the mitochondria and the impact on OxPhos.

Collectively, previous studies have suggested that the crystalloid-perfused heart is at or near the brink of functional hypoxia, implying that the metabolic reserve capacity of the perfused heart is limited. Consistent with this notion, crystalloid-perfused hearts are highly sensitive to changes in perfusate oxygenation: a small reduction in arterial Po2 decreases Mb oxygen saturation (33), shortens the action potential duration (APD) (20), and increases in mitochondrial NADH (43). Naturally, any changes in metabolic rate, such as increased heart rate (HR) or increased contractility, could induce mitochondrial hypoxia in the crystalloid-perfused heart.

Despite earlier studies that revealed Mb deoxygenation during crystalloid perfusion, the large discrepancy between the low oxygen affinity of Mb compared with cytochrome c oxidase (COX) makes it difficult to extrapolate the results of those studies to predict the impact of Mb deoxygenation on OxPhos. Therefore, a primary goal of the present study was to examine the mitochondrial oxygenation state under normal crystalloid-perfusion conditions and enhanced oxygen delivery with a perfluorocarbon (PFC) emulsion.

The redox state of the mitochondrial cytochromes and oxygenation of cytoplasmic Mb can be monitored using optical spectroscopy (1, 2, 8, 10, 13, 18, 23, 42). In the present study, we used a novel intrachamber probe to transmurally illuminate the LV wall to monitor changes in myocardial absorbance at high temporal resolution (18). The most physiological, but technically challenging, manner of increasing oxygen delivery is the use of RBCs (7, 12, 16, 32, 34). However, we have found that the remarkably high light absorbance in RBC-perfused hearts masks the detection of the mitochondrial chromophores, even during metabolic extremes, such as hypoxia. This is consistent with the modeling of RBC absorbance in the heart in vivo (19). To monitor the mitochondrial cytochromes and cytosolic Mb absorbance in the perfused heart, a perfusate with low visible light absorption (400–650 nm) and high oxygen carrying capacity needs to be developed.

PFCs are chemically inert compounds that act as oxygen carriers when properly prepared and have a linear relationship between Po2 and oxygen content (14, 39, 47). In addition to their oxygen carrying capacity, PFC suspensions are optically white and simply scatter light with no specific absorbance, making them a suitable candidate for optical studies in perfused hearts. While they were originally developed for medical applications as a potential blood substitute for transfusions, organ transplants, and battlefield medicine (26, 38, 39, 47), PFCs were not successfully translated to in vivo human use due to chronic toxicity. Important for this study, no acute impact of these agents on organ functions has been reported, underscoring the potential benefit of using PFCs in terminal perfusion experiments. Some commercial sources are still available, but the cost is exorbitant, making commercial PFC use for laboratory activities likely cost prohibitive. Thus, we tested whether, for acute studies (60–90 min), laboratory-synthesized PFCs might provide a tool to increase oxygen delivery to perfused hearts while providing direct detection of Mb and mitochondrial chromophores to evaluate the oxygenation of distinct cellular compartments.

The objectives of the present study were to 1) synthesize a laboratory-based PFC perfusate that supports the oxygenation of ex vivo perfused working hearts and is also affordable for typical cardiovascular laboratories and compatible with optical assessments of myocardial physiology and 2) characterize cardiac function and cytosolic and mitochondrial oxygenation of LV working rabbit hearts during KH perfusion and during perfusion with KH supplemented with PFC to increase oxygen delivery to the myocardium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PFC synthesis and characterization.

A suspension of 70% perfluorooctyl bromide (PFOB; Fluoryx) and 3% perfluorodecyl bromide (PFDB; Synquest Laboratories) was prepared according to Maillard et al. (29) with modifications. Soybean asolectin (28 g) was dissolved in 380.4 ml distilled H2O using a homogenizer (IKA) fitted with a wide-ended probe at 8,000 rpm for 10 min. PFDB (18 g) was slowly added while homogenizing at 8,000 rpm for an additional 5 min. PFOB (420 g) was added dropwise under mixing at 8,000 rpm using a Pasteur pipette. This mixture was then homogenized continuously for 30 min at 17,000 rpm in a glass water-jacketed flask connected to a water bath at 16°C.

The mixture was then split in half, and each half underwent sonication on ice for six cycles of 20 s with 60 s of rest. The sonicated suspension was subjected to three cycles of shearing to decrease particle size in a M-110P instrument (Microfluidics) with pressure set at 24,000 psi. This suspension could be stored overnight at 4°C. Before an experiment, the suspension was diluted 1:1 (resulting in a final concentration of 35% PFOB and 1.5% PFDB) with 2× crystalloid perfusion solution (KH, see below) and filtered through a 5.0-μm membrane.

Particle size was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using the DynaPro NanoStar DLS instrument (Wyatt). DLS measures the time dependence of the fluctuations in light scattering of molecules in solution, allowing the determination of the diffusion coefficient of a spherical particle, which is directly related to its radius. A representative PFC emulsion was diluted 1:10,000 in KH, and 0.1 ml of this suspension was placed in a plastic cuvette inside the DLS instrument. The time dependence of fluctuations in light scattering due to diffusion of the particles was analyzed by the instrument software, which calculated that a single population of particles with an average radius of 93 ± 7 nm was present in the suspension.

The oxygen content of the PFC emulsion was measured in suspensions of mitochondria by assaying the change in Po2 with a known amount of ADP in the presence and absence of PFC at the concentration used in this study. Pig heart mitochondria were isolated according to Chess et al. (13). Mitochondria were suspended in solution containing (in mM) 137 KCl, 20 HEPES, 15 NaCl, 1 EDTA, 1 EGTA, 5 MgCl2, 5 glutamate, 5 malate, and 5 potassium phosphate (pH 7.1) with and without PFC. Oxygen consumption was measured in a water-jacketed, oxygen-tight, well-mixed glass chamber with a Clark electrode in contact with the mitochondrial suspension as previously reported from this laboratory (31). The difference in the change in Po2 with the addition of identical amounts of ADP with and without PFC was taken as the buffer capacity of the PFC over a wide range of initial Po2.

The effect of PFC on free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]f) was determined using a combination Ca2+ electrode (MG Scientific). CaCl2 was titrated into either distilled water or PFC diluted to 35% PFOB and 1.5% PFDB with distilled water, as used in this study. The slope of the logarithmic [Ca2+]f-voltage relationship did not differ between distilled water (n = 5) and PFC (n = 3, 0.57 ± 0.01 and 0.56 ± 0.03). Additionally, using the relationship defined by the CaCl2 titration experiment, [Ca2+]f was determined in PFC samples after dilution with 2× KH (described below) at the conclusion of perfusion experiments. In these samples (n = 4), [Ca2+]f was determined to be 2.2 ± 0.1 mM, consistent with no effect of PFC on the Ca2+ activity in the concentrations used in this study.

Heart excision and perfusion for optical absorbance spectroscopy experiments.

All animal protocols were approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and performed in accordance with guidelines described in the Animal Care and Welfare Act (7 USC 2142 §13). New Zealand White rabbits (2.2–3.5 kg) were anesthetized with a mixture of 50 mg/kg ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg acepromazine, and 5 mg/kg xylazine intramuscularly. Isoflurane was administered via a mask to supplement the ketamine-xylazine. A venous line was placed in the marginal ear vein, 5,000 USP units/kg heparin was injected, and rabbits were euthanized with the injection of ~3 ml of 2 mEq/ml potassium chloride into the venous line. A thoracotomy was performed, and hearts were rapidly excised and retrogradely perfused in Langendorff (Lang) mode using a working heart perfusion system (AD Instruments). All hearts were perfused via the aorta within 120 s of excision.

To ensure that the flow capacity of the AD Instruments system was sufficient for the flow requirements of a rabbit heart (roughly 2× maximal cardiac output), the LV working heart perfusion apparatus required the following modifications. First, an internal diameter of >5 mm was required for all tubing that contained perfusate. Second, maximum-diameter T connectors were used to connect perfusate tubes, and flow through the system was controlled by clamping tubes shut with hemostats rather than restrictive three-way valves; indeed, the entire perfusion system was free of standard three-way valves. Third, the left atrial preload bubble trap required a capacity of at least 150 ml to ensure that no bubbles entered the left atria, even at high aortic outputs. Throughout all experiments, reserve perfusate delivery capacity was monitored by the overflow from the left atrial preload reservoir. Fourth, the system was outfitted with an upper compliance chamber having a diameter of 6 cm and 200 ml of dead space. Fifth, specific modifications for PFCs included the incorporation of two 12-μm filters in parallel to filter the perfusate before entering the left atrial preload reservoir. Additionally, tubing with an internal diameter of at least 1.5 cm for the overflow of the left atrial preload reservoir was necessary to maintain laminar flow and prevent bubbles from forming in the overflow tubing. KH and PFC perfusates were buffered with HEPES and oxygenated with 100% O2 instead of using bicarbonate and 95% O2-5% CO2 because CO2 is more soluble in PFC than oxygen (40), making pH difficult to adjust and reducing Po2 by 5%. In theory, more physiological CO2 levels could be used if the added Po2 was not needed and pH was calibrated in the presence of PFCs. Finally, to maintain high Po2 while minimizing foam formation, PFC perfusate was oxygenated with 100% O2 in the stock reservoir with a single small-diameter tube instead of an oxygenating bubbler (Radnoti), as was used to oxygenate KH. 100% O2 was blown over the left atrial preload container in both conditions to minimize the loss to room air. The initial perfusate was modified KH solution maintained at 37°C and pH 7.4 that contained 10 U/l insulin and (in mM) 115 NaCl, 3.3 KCl, 2.2 CaCl2, 1.4 MgSO4, 1.0 KH2PO4, 5.0 glucose, 1.0 lactate, and 25 HEPES. Aortic preload pressure was set to 65 mmHg by chamber height. While in Lang mode, under constant pressure perfusion, the pulmonary veins and vena cavae were ligated, and the left atria and pulmonary artery were cannulated. Left atrial preload pressure was 7–10 mmHg, and aortic afterload pressure was 55 mmHg by filling chamber heights. Hearts remained in Lang mode an average of 12.6 ± 1.1 min before being switched to LV working mode.

Aortic and left atrial pressures were measured continuously. HR was calculated from the aortic pressure fluctuations. In-line flow sensors were used to monitor CF and aortic output (Transonic). Cardiac output was calculated as the sum of CF and aortic output, and stroke volume was calculated by dividing cardiac output by HR. Coronary vascular resistance was calculated by dividing CF by minimum aortic pressure.

In a subset of hearts, arterial (via left atrial input) and venous (via coronary artery) perfusate oxygenation was monitored using NeoFox optical oxygen sensors (Ocean Optics). Optical oxygen sensors were calibrated separately for KH and PFC perfusate. A 0% oxygen calibration point was established by bubbling KH and PFC with 100% N2, and a 100% oxygen calibration point was established by bubbling KH and PFC with 100% O2. Signals were acquired via a PowerLab unit (AD Instruments). The myocardial oxygen consumption rate was calculated using arterial Po2 (; in mmHg) and venous Po2 (; in mmHg) and CF rate (CFR; in ml/min) according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where αc is the solubility of oxygen in KH (1.30 × 10−6 M/mmHg at 37°C), according to Schenkman (33). For myocardial oxygen consumption and oxygen content calculations in hearts perfused with PFCs, αc multiplied by 3.62 (measured as described above), the fold increase in oxygen carrying capacity of PFC perfusate compared with KH.

Myocardial optical absorbance spectroscopy.

Changes in transmural visible light absorbance were measured from the LV free wall using a custom-designed white LED catheter placed in the LV cavity and a rapid scanning spectrometer (model QE65PRO, Ocean Optics), as we have previously described elsewhere (18). The LED catheter was fed into the working heart system through a hemostasis valve and through the aortic valve when the heart was perfused with KH in LV working mode. The hemostasis valve was closed to hold the catheter in place and light from the “side-firing” LED illuminated the LV from the endocardium. Transmitted light was collected with a fiber optic light guide (2 mm diameter, Thorlabs) placed ~1 cm from the LV perpendicular to the maximum transmitted light intensity. Our previous study (18) has revealed that the insertion of the LED catheter in the LV cavity had minimal impact on the performance of the heart. Light intensity within the entire spectral range of the spectrometer (1,044 points, 348.82–742.03 nm) was recorded. Transmural optical spectra were collected at either 0.5, 1, 2, or 100 Hz, depending on the time requirements of the experimental protocol, using a custom-designed program (LabVIEW); 100-Hz data were used to analyze spectral differences between systole and diastole. After it was determined there were no differences in Mb oxygenation or cytochrome redox status between systole and diastole, other data collection rates were chosen to minimize the total file space needed, with no concern about whether the systole and diastole data were being pooled. That is, with the exception of the cardiac cycle experiment, all spectral data were averaged across collections at both systole and diastole, and acquisition rates were set by time resolution required, rather than over sampling in time, that led to data storage and processing issues. The rates used were the aforementioned 100 Hz for the cardiac cycle experiment, 2 Hz for transitions from KH to PFC, 1 Hz for KH to PFC back to KH transition and deoxygenation experiments, and 0.5 Hz for long-term stability experiments.

Experimental protocol.

First, the effects of transitioning from KH to PFC perfusate in the working heart were investigated. During perfusion with KH in LV working heart mode, HR, CF, and aortic output were allowed to stabilize before the perfusate was switched from KH to PFC. Hearts were perfused with KH in LV working heart mode for 11.5 ± 1.8 min before the switch. While recording CF, aortic output, and aortic pressure, and in a subset of experiments, arterial and venous perfusate oxygenation and transmural optical spectra, the perfusate entering the left atria was switched from KH to PFC. For these experiments, spectra were acquired at 2 Hz. Data were continually acquired as the perfusate was transitioned from KH to PFCs and until HR, CF, and aortic output stabilized, an average of 6.5 ± 1.2 min.

In a subset of experiments, the effect of switching from KH to PFC and back to KH was tested to ensure there were no sustained effects of the PFCs on cardiac function or mitochondrial redox status. In these experiments, each heart was allowed to stabilize HR, CF, and aortic output during perfusion with KH before being switched to PFC. Once HR, CF, and aortic output stabilized during PFC perfusion, the perfusate was switched back to KH. Hearts were perfused for an average of 8.9 ± 2.8 min with KH before being switched to PFC and then an average of 7.5 ± 1.3 min before being switched back to KH. Spectral data were collected at 1 Hz in these experiments.

After stabilizing with PFC perfusion, LV working hearts underwent either 1) a gradual hypoxia protocol or 2) a cardiac function stability protocol. For gradual hypoxia experiments, PFC perfusate was bubbled with nitrogen gas to progressively reduce perfusate oxygenation and thus arterial oxygen content. Transmural optical spectra were acquired at 1 Hz for these gradual hypoxia experiments. For cardiac function stability experiments, hearts were monitored for 60 min while transmural optical spectra were continuously acquired at 0.5 Hz.

The gradual hypoxia protocol and cardiac function stability protocol were also performed in hearts that were perfused with KH in LV working heart mode for comparison with PFC perfused hearts. Hearts underwent gradual deoxygenation 34.0 ± 8.6 min (KH) and 30.9 ± 3.1 min (PFC) after being switched to LV working mode. The total time of the gradual deoxygenation was 8.8 ± 0.6 min. Stability data collection was standardized and began 20 min after the transition to LV working mode.

Spectral data processing.

Changes in myocardial absorbance were calculated as a change in spectral optical density (ΔOD, Eq. 2) using spectra (Iλ) acquired during the baseline condition [Iλ at time 0 (t0)] and during experimental perturbations [Iλ at times i (ti)], as follows:

| (2) |

The baseline condition was KH perfusion immediately before the perfusate was transitioned from KH to PFC. In the gradual hypoxia experiments the baseline condition was normoxia.

The contribution of specific chromophores to ΔOD spectra at each time point were quantified by fitting a set of reference spectra to each ΔOD spectra, using a least-squares fitting approach implemented in a custom program (LabVIEW), as we have previously described elsewhere for perfused hearts (13, 18, 22). The set of reference spectra contained previously acquired difference spectra (13) (denoted as λ) for fully reduced minus fully oxidized cytochromes a,a3 (a605), cytochrome blow (bL), cytochrome bhigh (bH), cytochrome c (c), cytochrome c1 (c1), and Mb as well as the spectra of the LED white light source (Io). The peroxy cytochrome a,a3 (a607) species was not used in these fits, because we were investigating the presence of hypoxia, which does not generate the peroxy form (13). ΔOD and reference spectra were zeroed at a wavelength of 630 nm before least-squares fitting. A linear straight line with a variable fixed slope (m) and offset (b) across the spectrum was applied (coefficient x9 in Eq. 3) (13, 18). Fitted ΔOD spectra (ΔOD*, Eq. 3) were computed using the reference set. Chromophore contributions to ΔOD were quantified using the fitting coefficient (xi) associated with each chromophore as follows:

| (3) |

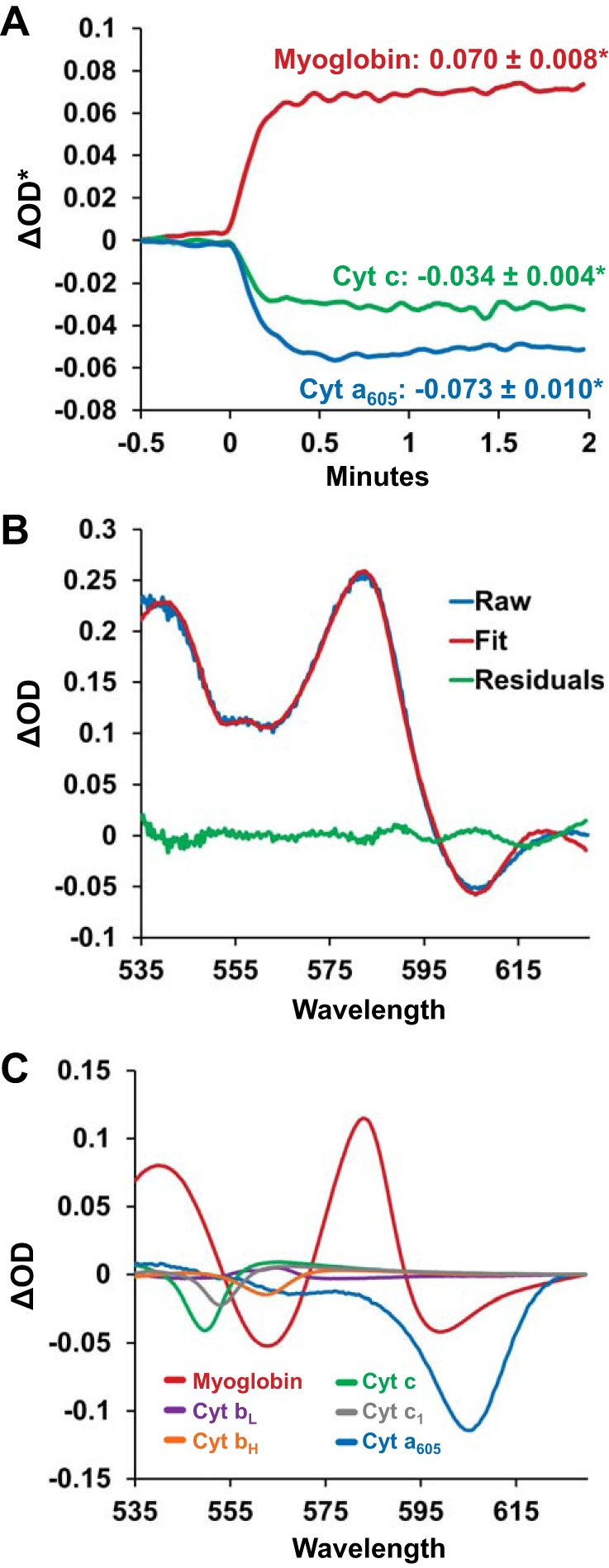

Maximum absorbance difference in all ΔOD spectra fell within 535–630 nm, so spectral fitting was restricted to this band to optimize chromophore selectivity (see residuals in Fig. 1B). The ratios of c1 and c were fixed based on the ratio detected in the fully reduced to fully oxidized difference spectrum in a whole heart homogenate, as previously described elsewhere (4, 18).

Fig. 1.

Changes in transmural absorbance spectra, and the underlying chromophores, when left ventricular working hearts were transitioned from Krebs-Henseleit (KH) to perfluorocarbon (PFC) perfusate. A: changes in myoglobin (red line), cytochrome (Cyt) c (green line), and cytochrome a605 (blue line) from a representative experiment when the perfusate was transitioned from KH to PFC at minute 0. Upon the transition, the oxygen saturation of myoglobin increased, as indicated by an increase in the fitted change in spectral optical density (ΔOD*) for myoglobin. Cytochromes a605 and c were oxidized, indicated by a decrease in ΔOD*. Values represent averages of n = 11 ± SE. *Significantly different from baseline. B: representative KH to PFC absorbance difference spectra. The raw difference spectra between PFC and KH perfusion (blue line) is shown with the fitted spectra (red line) and the residuals of the fit (green line). C: the spectral contribution of each chromophore to the resulting fitted spectra shown in B. Each reference spectra was scaled by its fitting coefficient that was determined during the least-squares spectral fitting algorithm.

Changes in the absorbance of each chromophore were monitored throughout experimental interventions by computing ΔOD* at specific wavelengths using the fitting coefficients. For example, during a KH to PFC transition, the fitting coefficients for Mb and cytochromes a605 and c were multiplied by the amplitude of the reference spectra at a chosen wavelength, thereby providing ΔOD* for each specific component. The wavelengths were 580 nm for Mb, 605 nm for cytochrome a, and 550 nm for cytochrome c.

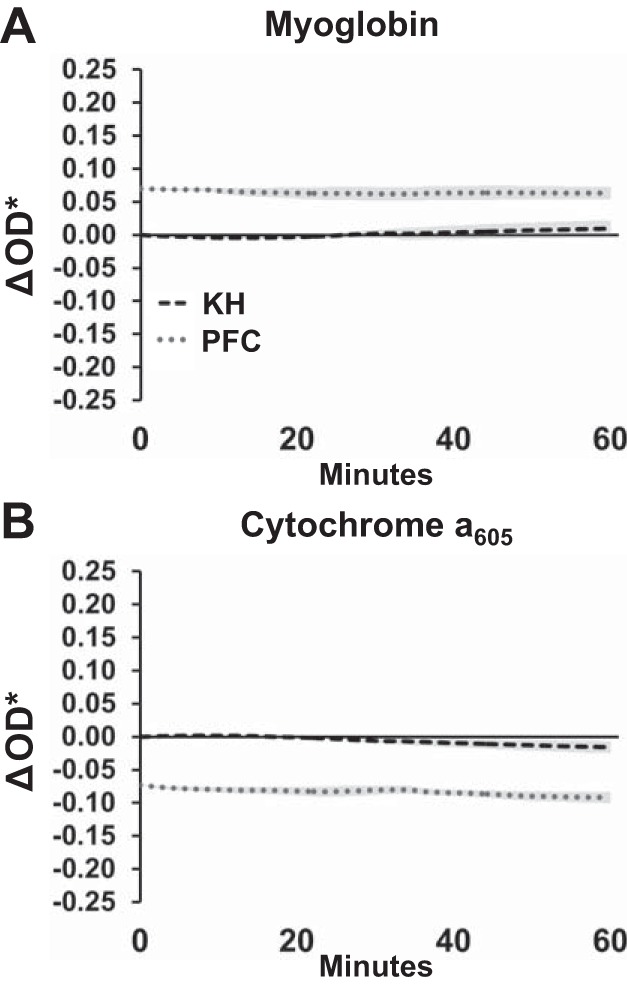

In the KH to PFC transition experiments, ΔOD* changes were calculated from baseline LV working heart perfusion with KH. An average of 50 data points was acquired for baseline. For deoxygenation data sets, a baseline average of 50 data points was acquired at maximal arterial oxygenation before initiating perfusate deoxygenation, and ΔOD* was calculated as changes from baseline. For PFC deoxygenation, these ΔOD* values were then offset by the average spectral change seen upon transition from KH to PFC (Fig. 1A). In the functional stability experiments, ΔOD* was calculated from a baseline average of 50 data points. ΔOD* values were calculated over the subsequent hour from that baseline. As before, for functional stability with PFC, these ΔOD* values were then offset by the average spectral change that occurred when KH perfusion was switched to PFC (Fig. 1A). For the functional stability experiments, ΔOD* was plotted on the full scale of ΔOD* values used to plot data from the deoxygenation experiments (see Fig. 5A).

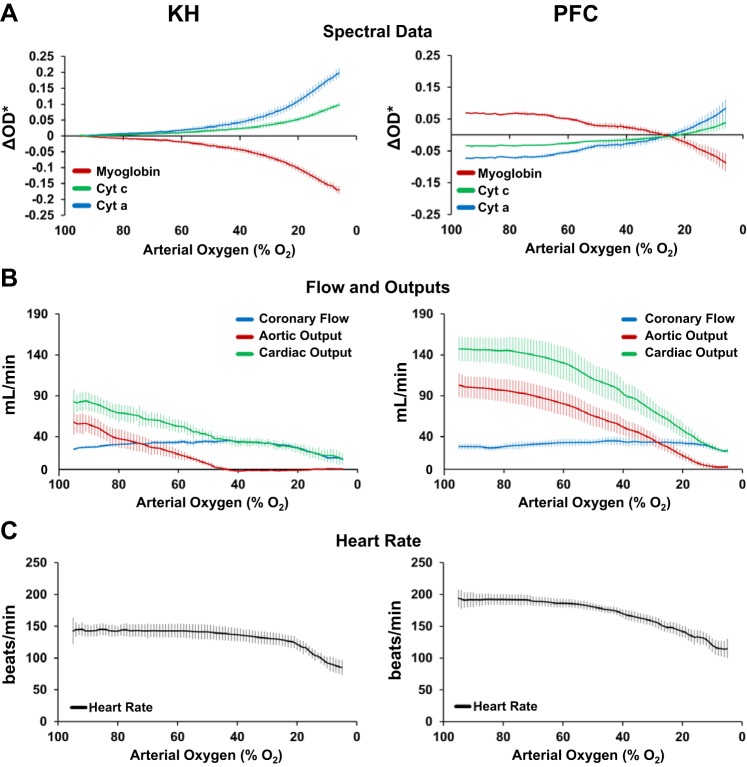

Fig. 5.

Effect of decreasing perfusate [either Krebs-Henseleit (KH) or perfluorocarbon (PFC)] oxygenation on cellular oxygenation, redox status, and cardiac function of left ventricular working hearts. A: during gradual perfusate deoxygenation, the myoglobin oxygen saturation decreases, indicated by a decrease in the fitted change in spectral optical density (ΔOD*), and cytochromes (Cyt) a605 and c become more reduced, indicated by an increase in ΔOD*. Data for KH perfusion were normalized to their respective baseline. Data for PFC perfusion were normalized to the average change in ΔOD* for data shown in Fig. 1A. KH: n = 6 and PFC: n = 7. B: effect of gradual perfusate deoxygenation on cardiac flow rates. With KH perfusion, aortic output dropped dramatically as soon as perfusate arterial oxygenation was lower than 90%. With PFC perfusion, aortic output was higher and better maintained. KH: n = 5 and PFC: n = 5. C: effect of gradual perfusate deoxygenation on heart rate. Heart rate was maintained at significantly higher levels with PFC perfusate at all levels of perfusate oxygenation. KH: n = 5 and PFC: n = 9. Data represent means ± SE.

Heart excision and perfusion for optical mapping experiments.

Animal protocols were approved by the George Washington University Animal Care and Use Committee. New Zealand White rabbits (2.2–3.5 kg, n = 6) were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of 44 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine. Heparin (2,000 units) was administered via an intravenous ear vein injection and allowed to circulate for 15 min. Rabbits were then subjected to inhalation of 5% isoflurane. After cessation of pain reflexes, the heart was quickly excised via thoracotomy and Langendorff perfused at 60 mmHg and 37°C on a biventricular working heart system (Hugo Sachs Elektronik) using the KH solution described above (20, 43). Hearts were stained while perfused with KH using 60 nmol of the voltage-sensitive dye di-4-ANEPPS dissolved in 30 μl of DMSO and then diluted in 3 ml perfusate and injected into the aorta. Hearts were paced at a cycle length of 290 ms (207 beats/min) during all optical mapping acquisitions.

Motion tracking and excitation ratiometry optical mapping.

Epicardial action potential signals were optically mapped using motion tracking with excitation ratiometry, as previously described (20, 49). Excitation LEDs (450 and 505 nm, Phillips Luxeon) were coupled to the inputs of two randomized quad fiber optic bundles (Schott), and the singular outputs were aimed at the LV epicardium of perfused rabbit hearts. A 460 ± 135-nm excitation filter and light diffuser were attached to the output of each light guide. A Pulsemaster A3400 cycled each of the two sets of LEDs to interlace epicardial illumination with the acquisition of di-4-ANEPPS fluorescence images, where even frames corresponded to 450-nm illumination and odd frames corresponded to 505-nm illumination. One high-speed EMCCD camera (iXon DV860, Andor Technology), fitted with a 635 ± 25-nm emission filter, acquired fluorescence images at 746 Hz during the experimental protocol, providing a frame rate of 373 Hz for each excitation wavelength. Circular fiducial markers were glued to the epicardium for tracking local contractile motion within the optically mapped region. Optical action potential (OAP) signals were then computed as the ratio of the motion-corrected fluorescence that was imaged at each excitation wavelength, as previously described (20, 49). OAP signals were spatially averaged within an epicardial region of ~15 mm2 on the anterior LV free wall. APD was measured from the average OAP signal as the average APD (±SD) of six action potentials within the signal. APD for individual OAPs was measured as the time interval between the maximum first derivative and the secondary peak of the second derivative (20, 49).

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SE. Raw data for HR, CF aortic pressures, and aortic output were found to be normally distributed using the Anderson-Darling test. Significant differences between data acquired during KH perfusion and PFC perfusion were identified using Student’s t-tests, with the appropriate modification for either paired or nonpaired data. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to determine significant differences during stability studies. P values of <0.05 were accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Perfusate oxygen carrying capacity.

KH supplemented with PFCs held 3.62 ± 0.09-fold more oxygen than KH alone based on the change in Po2 in response to the addition of known amounts of ADP to respiring mitochondria. The average phosphate:oxygen (P/O) in the absence of PFC was 3.38 ± 0.17 and in the presence of PFC was 12.2 ± 0.41, giving the average α-value above. With the methods of bubbling used, KH had a Po2 of 734 ± 13 mmHg and an oxygen content of 0.95 ± 0.02 mmol O2/l perfusate. KH supplemented with PFCs had a slightly higher oxygen content of 3.15 ± 0.07 mmol O2/l but a slightly lower Po2, 672 ± 15 mmHg (see Table 2). The small, ~10% difference in Po2 between KH and PFC was likely due to the oxygen buffering capacity of the PFCs, making it harder to attain high Po2. In addition, the bubbling techniques differed between KH and PFC, as explained in materials and methods: 100% O2 was introduced to KH via a fine oxygenating sintered glass bubbler and to PFC via a single tube to minimize foaming of the PFC perfusate.

Table 2.

Oxygen consumption in LV working heart with KH and PFC

| O2 Consumption Rate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Po2 In, mmHg | Po2 Out, mmHg | O2 Content, mmol O2/l medium | μmol O2·min−1g wet wt−1 | μmol O2/beat | |

| KH | 733 ± 13 | 69 ± 23 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 5.08 ± 0.30 | 0.24 ± 0.01 |

| PFC | 672 ± 15* | 297 ± 40* | 3.15 ± 0.07* | 6.74 ± 0.69* | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6. KH, Krebs-Henseleit; PFC, perfluorocarbon.

Significantly different from KH.

Myocardial mass.

Heart mass was used to normalize the functional and metabolic data, since animal sizes varied from 2.2 to 3.5 kg, with associated changes in heart mass. We did not attempt to measure the initial weights of the hearts, since speed of cannulation was imperative. On average, the hearts used in KH experiments had a wet mass of 6.18 ± 0.32 g, LV wet mass of 3.56 ± 0.17 g, and LV dry mass of 0.61 ± 0.03 g. Hearts used in PFC experiments had a wet mass of 8.89 ± 0.48 g, LV wet mass of 5.10 ± 0.26 g, and LV dry mass of 0.86 ± 0.06 g. It is important to note that the wet-to-dry ratios of these hearts under both conditions did not change, suggesting no major alteration in heart water or mass.

Improved function with elevated cytosolic and mitochondrial oxygenation.

Transitioning from KH to PFC perfusion in LV working hearts profoundly improved Mb oxygenation, cytochrome redox state, and overall contractile performance (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Most notably, compared with KH, perfusion with PFCs dramatically improved aortic output, doubling it from 76 ± 6 to 142 ± 4 ml/min. Along with this, peak aortic pressure increased by 24 ± 3%, from 77.1 ± 2.1 to 95.0 ± 2.5 mmHg. HR also increased, stabilizing 14 ± 3% higher after the transition to PFCs (Table 1). Altogether, the dramatic elevations of aortic output and HR resulted in a large increase in cardiac work after transitioning to PFCs.

Table 1.

Left ventricular working heart function with KH and PFC

| Heart Rate, beats/min | Coronary Flow Rate, ml/min | Aortic Output, ml/min | Cardiac Output, ml/min | Stroke Volume, ml/beat | Coronary Vascular Resistance, mmHg·min·ml−1 | Peak Aortic Pressure, mmHg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KH | 170 ± 5 | 42 ± 2 | 76 ± 6 | 118 ± 6 | 0.70 ± 0.04 | 1.26 ± 0.10 | 77.1 ± 2.1 |

| PFC | 191 ± 5* | 36 ± 3* | 142 ± 4* | 178 ± 5* | 0.94 ± 0.04* | 1.78 ± 0.16* | 95.0 ± 2.5* |

| n | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 13 | 13 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of animals. KH, Krebs-Henseleit; PFC, perfluorocarbon.

Significantly different from KH.

CF significantly decreased from 42 ± 2 to 36 ± 3 ml/min after transitioning to PFCs. This decrease in CF was accompanied by an increase in coronary vascular resistance from 1.26 ± 0.10 to 1.78 ± 0.16 mmHg·min−1·ml−1.

Absolute oxygen consumption rate, measured in a subset of the hearts, increased from 5.08 ± 0.02 to 6.74 ± 0.69 μmol O2·min−1·g wet mass−1 after transition to PFC. The similar values for the calculated oxygen consumption per beat (KH: 0.24 ± 0.01 μmol O2/beat and PFC: 0.28 ± 0.03 μmol O2/beat) reveals that the primary effect on total oxygen consumption was HR, consistent with previous studies (15, 22a, 30a, 42a).

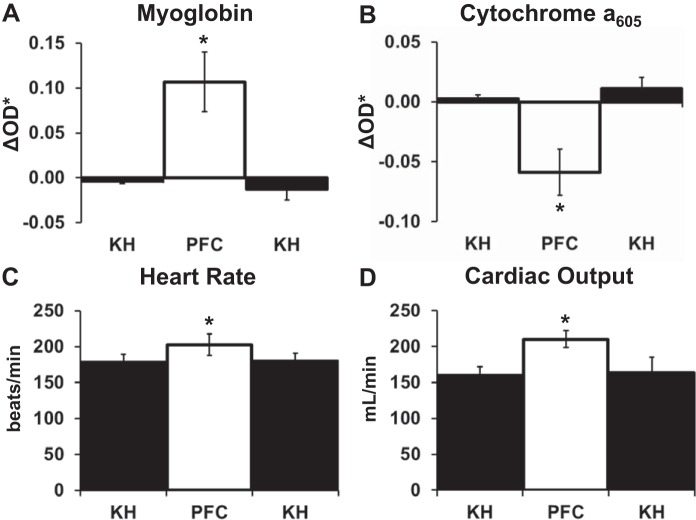

PFC perfusion increased Mb oxygenation and oxidized the cytochromes. Upon the transition from KH, when PFCs entered the left atria there was a rapid increase in Mb oxygenation, indicated by a ΔOD* increase, and an oxidation of both cytochromes a605 and c, indicated by a ΔOD* decrease. These changes stabilized within 1 min (Fig. 1A). The spectral fitting and contributions of the individual chromophores to the fit are shown in Fig. 1, B and C. These data are consistent with a net oxygenation of Mb but also, importantly, a net oxidation of the cytochromes, consistent with a significant increase in oxygenation at the level of the mitochondria. Moreover, these changes reverted when the perfusate was switched from PFC back to KH (Fig. 2, A–D).

Fig. 2.

Changes in cellular oxygenation, redox status, and cardiac function of left ventricular working hearts when perfusate was transitioned from Krebs-Henseleit (KH) to perfluorocarbon (PFC) and back to KH. A−D: average changes in myoglobin (A), cytochrome a605 (B), heart rate (C), and cardiac output (D) during KH perfusion, PFC perfusion, and KH perfusion after PFC perfusion. Data represent means ± SE; n = 4 for spectral data (A and B) and n = 6 for functional data (C and D). *Significantly different from baseline with KH.

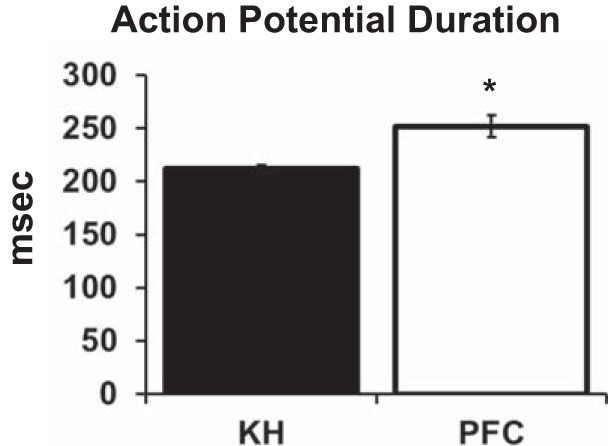

Optical APD changes in Langendorff-perfused hearts also indicated improved oxygenation with PFCs, as evidenced by an increase in APD with PFC perfusion. When paced at 207 beats/min, APD significantly increased when the perfusate was switched from KH to PFC: from 212 ± 3 ms with KH to 252 ± 10 ms with PFC perfusion (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Optical action potential duration during Langendorff perfusion with Krebs-Henseleit (KH) compared with perfluorocarbon (PFC). Optical action potentials were measured from the left ventricular epicardial surface while each heart (n = 6) was paced at 207 beats/min. Values are means ± SE of action potential duration. *Significantly different from KH.

Mb oxygenation and mitochondrial redox are constant throughout the cardiac cycle.

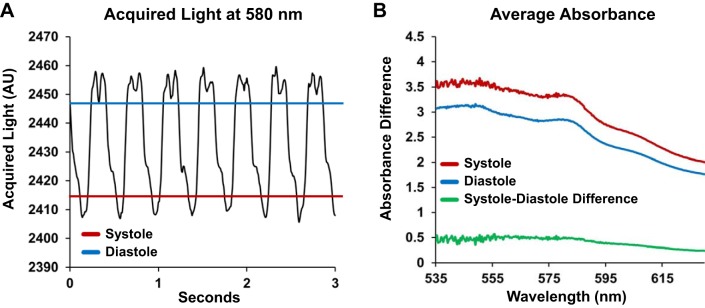

Transmural absorbance spectroscopy did not reveal changes in Mb oxygen saturation or cytochrome redox state during the cardiac cycle (Fig. 4), consistent with previous studies (17, 30, 40a). Acquired light is highest during diastole and lowest during systole, when the ventricular wall would be the thickest (Fig. 4A). When the spectral data were plotted, the shapes of the absorbance difference spectra were identical, simply offset due to changes in optical path length (Fig. 4B). The difference in absorbance spectra from systole and diastole was flat and did not reveal characteristics that were indicative of changes in chromophore redox state (Fig. 4B). These data supported our decision to average the spectra across beats, as described in materials and methods.

Fig. 4.

Transmural absorbance changes between acquisitions during systole and diastole are dominated by changes in pathlength. A: transmural light acquired from the epicardial surface was greatest during diastole (blue line) and was lowest during systole (red line). B: when transmural absorbance spectra acquired during systole were compared with spectra acquired during diastole, there was no spectral structure in the shape of the difference between the spectra (green line). n = 11.

PFC perfusate provided arterial oxygen reserve and maintained improved function.

To determine the oxygen reserve available to the myocardium, the oxygen content of the perfusate (either KH or PFCs), and thus arterial oxygen content, was lowered by bubbling the perfusate with N2 while monitoring functional parameters and spectral data. Spectral data were normalized to KH baseline for both KH and PFC data, as described in materials and methods.

During both KH and PFC perfusion, Mb oxygenation and cytochrome a605 and c redox status changed only slightly as arterial oxygenation was lowered from 95% to 60% (Fig. 5A). However, for these same perfusate oxygen levels, PFC perfusion maintained Mb at higher oxygenation, indicated as higher ΔOD* values, and the cytochromes were more oxidized, indicated as lower ΔOD* values. As arterial oxygenation fell below 60%, Mb began to deoxygenate, and the cytochromes became more reduced. The point in Fig. 5A where the curves for Mb, cytochrome c, and cytochrome a605 cross zero occurs at the PFC perfusate oxygen level between 22% and 28%. This result is important because it indicates that cellular oxygenation and mitochondrial redox status with PFC at 22–28% oxygenation is the same as that of KH perfusate at the baseline oxygenation level of 95%. Indeed, this is consistent with the absolute oxygen contents of the two perfusates: 95% oxygenation of KH perfusate corresponds to 0.94 μmol O2/l perfusate and 28% oxygenation corresponds to 0.25 μmol O2/l perfusate, whereas 28% oxygenation of PFC perfusate corresponds to 0.89 μmol O2/l perfusate, which is very close to the oxygen concentration of 95% oxygenated KH.

As the perfusate was deoxygenated, a higher aortic output was maintained longer and HR remained higher during perfusion with PFCs compared with KH (Fig. 5B). Aortic output dropped to zero in KH-perfused hearts when arterial oxygenation reached 43%, whereas aortic output was 57 ± 11 ml/min in PFC-perfused hearts at the same arterial oxygen level (Fig. 5B). HR was relatively constant with both perfusates until arterial oxygenation dropped below 40% (Fig. 5C).

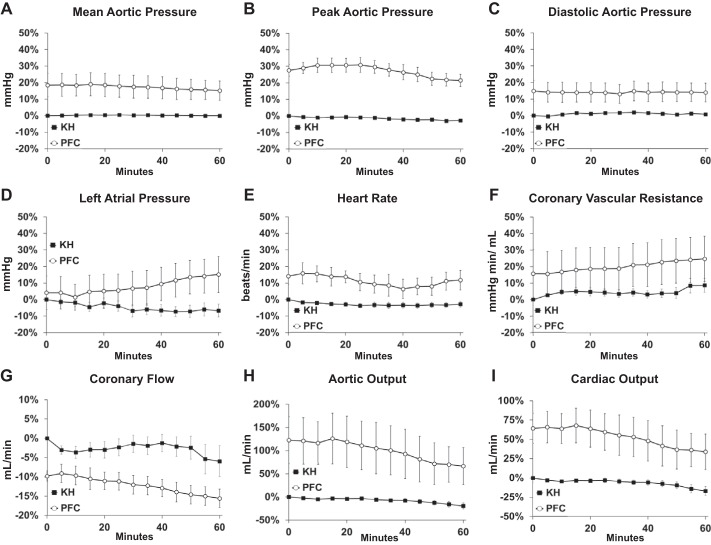

Both KH and PFC perfusates maintained myocardial function for at least an hour of LV working heart perfusion (Fig. 6). Stability data were normalized to baseline in KH-perfused hearts. In PFC-perfused hearts, stability data were normalized to the KH perfusion values measured before transitioning to PFC perfusion. Peak aortic pressure, aortic output, cardiac output, and HR were higher after an hour of perfusion with PFC compared with time 0 in KH-perfused hearts (Fig. 6 and Table 3). This indicates that, even after an hour of perfusion with PFC, LV working hearts had better performance than the early performance of hearts perfused with KH, the time when perfused heart performance is typically the best.

Fig. 6.

Functional stability of left ventricular working hearts perfused with Krebs-Henseleit (KH) or perfluorocarbon (PFC). A−C: percent changes of mean (A), peak (B), and minimum (C) aortic pressure over 60 min of perfusion with KH (n = 10) or PFC (n = 5). D−F: percent changes of mean left atrial pressure (D), heart rate (E), and calculated coronary vascular resistance (F) over 60 min of perfusion with KH (n = 10) or PFC (n = 5). G−I: percent changes in coronary flow (G), aortic output (H), and cardiac output (I) over 60 min of perfusion with KH (n = 10) or PFC (n = 5 for coronary flow and n = 4 for aortic and cardiac output). For A−I, KH was normalized to its own baseline; PFC was normalized to the KH baseline before the switch to PFC. Values are means ± SE.

Table 3.

Cardiac function at the beginning and end of stability experiments with KH and PFC

| Mean Aortic Pressure, mmHg | Peak Aortic Pressure, mmHg | Minimum Aortic Pressure, mmHg | Left Atrial Pressure, mmHg | Heart Rate, beats/min | Coronary Vascular Resistance, mmHg·min·ml−1 | Coronary Flow, ml/min | Aortic Output, ml/min | Cardiac Output, ml/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KH | |||||||||

| 0 min | 54.4 ± 0.5 | 71.8 ± 1.4 | 45.0 ± 0.9 | 9.3 ± 1.0 | 155 ± 8 | 1.44 ± 0.18 | 35 ± 6 | 66 ± 7 | 94 ± 11 |

| 60 min | 54.4 ± 0.5 | 69.8 ± 1.2 | 45.1 ± 1.1 | 8.5 ± 0.8 | 152 ± 8 | 1.64 ± 0.20 | 29 ± 5 | 53 ± 7 | 76 ± 8 |

| PFC | |||||||||

| 0 min | 65.8 ± 3.2 | 93.7 ± 6.9 | 56.6 ± 0.5 | 12.9 ± 2.6 | 180 ± 7 | 1.63 ± 0.29 | 39 ± 6 | 129 ± 17 | 166 ± 12 |

| 60 min | 64.1 ± 3.1 | 89.2 ± 6.7 | 56.1 ± 0.4 | 13.7 ± 2.1 | 177 ± 10 | 1.77 ± 0.32 | 35 ± 5 | 96 ± 19 | 132 ± 16 |

Values are means ± SE. Data represent average functional data shown in Fig. 6. KH, Krebs-Henseleit; PFC, perfluorocarbon; 0 min, beginning of the experiments; 60 min, end of the experiments.

Mb oxygenation and cytochrome a605 were also stable over an hour of perfusion with KH or PFC (Fig. 7). However, ΔOD* values in PFC-perfused hearts were offset from zero, reflecting the redox change observed during the KH to PFC transition. Indeed, this indicates that, compared with KH perfusion, LV working hearts perfused with PFCs initially have higher oxygenation and the cytochromes are more oxidized. We also found that PFC perfusion maintained these improved oxygenation levels for at least 1 h (Fig. 7). These data are shown with the ΔOD* range measured during deoxygenation (Fig. 5), illustrating that any changes in redox status over 1 h were small.

Fig. 7.

Stability of myoglobin oxygenation and cytochrome a650 redox state in left ventricular working hearts perfused with Krebs-Henseleit (KH) or perfluorocarbon (PFC). Data are shown with the fitted change in spectral density (ΔOD*) range measured during deoxygenation (Fig. 3, A and B), illustrating that any changes over 1 h were small. KH was normalized to its own baseline; PFC was normalized to the average change shown in Fig. 1A. Data reported as means ± SE; n = 4–5.

DISCUSSION

Ideally, excised heart preparations would represent in vivo conditions and reproduce in vivo myocardial function. The level to which this can be achieved is questionable, particularly in light of reports suggesting that perfusion with crystalloid media results in a mismatch between myocardial oxygen supply and demand. Here, we demonstrate that cardiac Mb deoxygenation in crystalloid perfused hearts is accompanied by a high reduction state of the mitochondrial cytochromes, including COX, despite its high affinity for oxygen. Our data indicate that OxPhos and downstream cardiac output are dramatically impaired in contrast to the in vivo situation (1, 3). To overcome the limitation of delivering oxygen to the perfused working heart, and in pursuit of reproducing in vivo myocardial function, we describe the synthesis of a laboratory-based PFC perfusate for short-term perfusion of excised hearts. This perfusate results in an energetically beneficial mitochondrial redox state and elevated Mb oxygenation that significantly improve myocardial function and double aortic output. Of particular importance, this PFC perfusate does not significantly interfere with the monitoring of Mb oxygenation and cytochrome redox status using visible light assessments. The combined technologies of transmural optical absorbance spectroscopy and PFC emulsion perfusion are a powerful enhancement to conventional ex vivo heart approaches and increase the physiological sophistication of investigations into cardiac physiology, pharmacology, and disease.

PFCs improve oxygenation and function.

Increasing the delivery of oxygen to the myocardium by supplementing traditional KH with PFCs dramatically increased cardiac work and improved function. Aortic output doubled almost immediately when LV working hearts were transitioned from KH to PFC perfusate, and peak aortic pressure and HR increased (Table 1). This increase in cardiac work with PFC was accompanied by an increase in , an oxygenation of Mb, and an oxidation of the mitochondrial cytochromes, indicating improved cellular and mitochondrial oxygenation (Fig. 1A and Table 2). These changes occurred despite there being no increase in ; in fact, was slightly lower with PFCs (Table 2). These data strongly indicate that ex vivo LV working perfused hearts are operating at an oxygen limitation that extends to the mitochondria and results in an adaptive repression of work output, perhaps similar to that of hibernating myocardium.

The present study is the first to demonstrate that Mb oxygenation and mitochondrial redox status are beneficially affected by adding an exogeneous oxygen carrier to crystalloid-based perfusate. When the PFC-supplemented KH was administered to a LV working heart, Mb oxygen saturation increased, consistent with data that report that Mb is only 72% saturated in the crystalloid-perfused LV working guinea pig heart and 93% saturated with a perfusate with 5% hematocrit (34). While these data indicate that the oxygenation of the cytosol is compromised with KH perfusion, it was unknown whether this affected the mitochondrial cytochromes. We have now demonstrated that upon perfusion with PFC, cytochromes c and a605 become more oxidized, consistent with the removal of an oxygen limitation for OxPhos (Fig. 1). Additionally, the longer APD observed during PFC perfusion compared with KH perfusion further indicates that PFC improves mitochondrial oxygenation, promoting the closure of ATP-sensitive K+ channels and resulting in the lengthening of APD.

An increase in oxygen consumption rate, as was observed with perfusion with PFCs, is expected to result in an increase in reduced cytochrome a in the peroxy form. The reduction level of cytochrome a is a primary regulator of flux through COX and maintains a positive, linear relationship with oxygen consumption rate (13, 22, 45). In our experiments, the increase in peak aortic pressure, aortic output, HR, and myocardial oxygen consumption upon the switch to PFC perfusion occurred simultaneously with an oxidation of the fully reduced (i.e., hypoxia) cytochrome a605 species, not an increase in the peroxy form predicted from isolated mitochondrial experiments. This result suggests that the increase in myocardial oxygen consumption with PFC was not due to increasing work directly but by relieving the oxygen limitation at COX, as witnessed by the oxidation of the cytochrome a605 species.

It is important to note that the PFC perfusate used in the acute experiments of this work and others has not been correlated with any detrimental short-term pathophysiological effects on the heart (11, 36). Chronic administration of PFCs in the whole body has detrimental effects, but these are not associated with direct cardiotoxicity (46). In our experiments, PFC perfusate improved cardiac function in acute administration (60–90 min) without any observed cardiotoxic effects. As a result, we propose that PFC perfusate is a significant enhancement to the conventional ex vivo implementation of the crystalloid perfused heart.

PFC perfusate maintained improved function and redox status during arterial deoxygenation.

A notable observation was the high sensitivity of aortic output to perfusate oxygenation. Aortic output robustly increased when hearts were perfused with PFCs (Table 1). Aortic output also dropped dramatically with reductions in arterial oxygenation (Fig. 5); however, aortic output for KH-perfused LV working hearts was more sensitive. Aortic output decreased by 50% in KH-perfused hearts when arterial oxygenation decreased to 70%, whereas a 50% change in aortic output was not observed with PFC until arterial oxygenation fell to 40%. Most notably, hearts perfused with KH ceased to generate adequate pressure to produce any aortic output when arterial oxygenation fell below 43%, whereas aortic output was still being generated at 10% oxygenation in PFC-perfused hearts (Fig. 5B). PFC-perfused hearts maintained improved cellular and mitochondrial oxygenation during arterial deoxygenation due to the effects of PFC on baseline normoxic function. The increased Mb oxygenation, indicated by a higher ΔOD*, and oxidation of the cytochromes, indicated by a lower ΔOD*, with PFC compared with KH perfusion was maintained until PFC oxygenation reached ~25%. At that point, ΔOD* values for Mb, cytochrome c, and cytochrome a605 are approximately zero. As mentioned above in the results, this crossover point is of note, as this value approximates the point at which KH and PFC perfusates have equal oxygen contents: at 95% O2, KH O2 content is 0.94 μmol/l, and at 28% O2, PFC O2 content is 0.89 μmol/l.

Despite the different apparent affinities for oxygen between Mb and COX, we found that decreases in oxymyoglobin and increases in reduced cytochrome a605 occur concomitantly during gradual perfusate deoxygenation (Fig. 5A). COX is the final electron acceptor of the electron transport chain, with P50 on the order of 0.5−0.05 µM (9, 48), whereas P50 of Mb is ~2–3 µM (35, 48). On the basis of these large differences in oxygen affinity, one would predict that Mb would deoxygenate at a much higher Po2 than COX; however, we found cytochrome a605 to be as sensitive to decreases in oxygenation as Mb in situ. This leads to the conclusion that Mb deoxygenation is occurring simultaneously with oxygen limitations in the mitochondria.

Others have seen this type of correlation between Mb oxygenation and cytochrome oxidase redox state in the perfused heart with an explanation that there is a steep oxygen gradient through the cytosol (6, 18, 41, 42, 44). This would be consistent with small, local regions of tissue total anoxia where Po2 is below the saturation level of both Mb and cytochrome oxidase in saline-perfused hearts that were eliminated by the PFC addition. It has been shown in some conditions that punctate anoxia can be present in the perfused heart (5); however, this was not observed in NADH epicardial images of the KH-perfused rabbit heart in our laboratories (43). Others have claimed that the oxygen affinity of cytochrome oxidase is much lower in vivo (24). Clearly, the actual mechanism by which Mb oxygenation and cytochrome oxidase redox state track each other in intact hearts in several laboratories is still unresolved.

Ease of preparation and utility of PFC perfusate.

Perfusion with whole blood or perfusate supplemented with erythrocytes improves the electromechanical function of excised perfused hearts (12, 16, 21, 32). However, perfusion with such solutions is difficult due to multiple technical challenges. Additional animals are usually required to provide adequate circulating blood volume for a perfusion system, which also necessitates diligent filtering of the perfusate. Additionally, the control of metabolic substrate and other bloodborne agents can be difficult unless the erythrocytes are removed from the blood, washed, and resuspended in KH, requiring additional preparation for each experiment. The PFC perfusate presented here can be made in <3 h, stored overnight for use the next day, and does not contain unknown organic material. We have found that our PFC perfusate can be recirculated by in-line filtering of the perfusate using two 12-µm filters in parallel.

One limitation of both KH and PFC perfusates is their requirement of being bubbled with 100% O2 to maximize oxygen carrying capacity. Due to its sigmoidal oxygen-binding characteristics, hemoglobin is almost fully saturated with oxygen at a Po2 of 100 mmHg, whereas KH and PFC oxygenation is linearly related to Po2, requiring bubbling with 100% O2 to maximize oxygen carrying capacity. Therefore, both KH and PFC perfusates have supraphysiological Po2 compared with erythrocyte-based oxygen carriers that could have physiological effects on the cells experiencing this high Po2. Additionally, at low Po2 values, neither KH nor PFC have the benefit the rapid offloading of O2 at low Po2 that hemoglobin provides.

Hemoglobin or erythrocytes, however, interfere with optical assessments of myocardial physiology, a critical limitation in all experiments where myocardial absorbance or fluorescence in the visible light band are planned to be measured. In contrast, our PFC perfusate is white with no specific absorbance, but light scattering is high due to the micelle structure of the PFC. In considering the high light-scattering properties of the myocardium (18), any additional scattering of the PFC within the vessels does not significantly impact optical measurements. Indeed, our PFC perfusate is compatible with many visible light assessments, including absorbance spectroscopy and fluorescence imaging (Figs. 1 and 3). Moreover, PFCs could potentially be used with a variety of fluorescent dyes, such as fluorescent cytosolic Ca2+ and pH indicators.

Summary

We found that the mitochondria of crystalloid perfused LV working hearts are limited by oxygen delivery, as evidenced by the redox status of COX. This limited oxygen delivery is associated with an adaptive, dramatically depressed cardiac work. To overcome this limitation, and in pursuit of the ideal of reproducing in vivo myocardial function, we synthesized a laboratory-based PFC emulsion perfusate for short-term perfusion of excised hearts. This perfusate increases arterial oxygen content, oxygenates Mb, oxidizes COX, doubles aortic output, increases HR, and increases myocardial oxygen consumption. The optical properties of the PFC perfusate do not significantly interfere with visible light assessments of myocardial physiology. The combined technologies of transmural rapid-scanning optical absorbance spectroscopy and PFC emulsion perfusion are a powerful enhancement to conventional ex vivo heart approaches and increase the physiological sophistication of investigations into cardiac physiology, pharmacology, and disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-095828 and R21-HL-132618 (to M. W. Kay) and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 14POST20490181 and Scientific Development Grant 16SDG30770015 (to S. Kuzmiak-Glancy). R. S. Balaban, B. Glancy, A. N. Femnou, R. Covian, and S. A. Fench were supported by the intramural program at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.K.-G., R.C., B.G., A.M.W., K.G., and S.F. performed experiments; S.K.-G., A.N.F., B.G., R.J., and R.S.B. analyzed data; S.K.-G., B.G., R.S.B., and M.W.K. interpreted results of experiments; S.K.-G. prepared figures; S.K.-G. drafted manuscript; S.K.-G., B.G., R.S.B., and M.W.K. edited and revised manuscript; S.K.-G., R.C., A.N.F., B.G., R.J., A.M.W., K.G., S.F., R.S.B., and M.W.K. approved final version of manuscript; R.S.B. and M.W.K. conceived and designed research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Jack Rogers and Hanyu Zhang for the expertise in guiding our implementation of their approach to motion tracking optical mapping with excitation ratiometry. We thank Joni Taylor, Shawn Kozlov, and Kathy Lucas for animal care and support. We thank Elizabeth Murphy for helpful comments in the preparation of the manuscript. We are also grateful to Alexander Kelly for the use of the M-110P instrument.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arai AE, Kasserra CE, Territo PR, Gandjbakhche AH, Balaban RS. Myocardial oxygenation in vivo: optical spectroscopy of cytoplasmic myoglobin and mitochondrial cytochromes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H683–H697, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakaki LSL, Burns DH, Kushmerick MJ. Accurate myoglobin oxygen saturation by optical spectroscopy measured in blood-perfused rat muscle. Appl Spectrosc 61: 978–985, 2007. doi: 10.1366/000370207781745928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bache RJ, Zhang J, Murakami Y, Zhang Y, Cho YK, Merkle H, Gong G, From AHL, Ugurbil K. Myocardial oxygenation at high workstates in hearts with left ventricular hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 42: 616–626, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balaban RS, Mootha VK, Arai A. Spectroscopic determination of cytochrome c oxidase content in tissues containing myoglobin or hemoglobin. Anal Biochem 237: 274–278, 1996. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow CH, Chance B. Ischemic areas in perfused rat hearts: measurement by NADH fluorescence photography. Science 193: 909–910, 1976. doi: 10.1126/science.181843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beard DA, Schenkman KA, Feigl EO. Myocardial oxygenation in isolated hearts predicted by an anatomically realistic microvascular transport model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1826–H1836, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00380.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergmann SR, Clark RE, Sobel BE. An improved isolated heart preparation for external assessment of myocardial metabolism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 236: H644–H661, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bose S, French S, Evans FJ, Joubert F, Balaban RS. Metabolic network control of oxidative phosphorylation: multiple roles of inorganic phosphate. J Biol Chem 278: 39155–39165, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chance B. Reaction of oxygen with the respiratory chain in cells and tissues. J Gen Physiol 49, Suppl: 163–188, 1965. doi: 10.1085/jgp.49.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chance B. Pyridine nucleotide as an indicator of the oxygen requirements for energy-linked functions of mitochondria. Circ Res 38, Suppl 1: I31–I38, 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chemnitius JM, Burger W, Bing RJ. Crystalloid and perfluorochemical perfusates in an isolated working rabbit heart preparation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 249: H285–H292, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen V, Chen YH, Downing SE. An improved isolated working rabbit heart preparation using red cell enhanced perfusate. Yale J Biol Med 60: 209–219, 1987. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chess DJ, Billings E, Covian R, Glancy B, French S, Taylor J, de Bari H, Murphy E, Balaban RS. Optical spectroscopy in turbid media using an integrating sphere: mitochondrial chromophore analysis during metabolic transitions. Anal Biochem 439: 161–172, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark LC Jr, Gollan F. Survival of mammals breathing organic liquids equilibrated with oxygen at atmospheric pressure. Science 152: 1755–1756, 1966. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3730.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncker DJ, Bache RJ. Regulation of coronary blood flow during exercise. Physiol Rev 88: 1009–1086, 2008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duvelleroy MA, Duruble M, Martin JL, Teisseire B, Droulez J, Cain M. Blood-perfused working isolated rat heart. J Appl Physiol 41: 603–607, 1976. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.41.4.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabel H. Normal and critical O~-supply of the heart. In: Oxygen Transport in Blood and Tissue, edited by Lubbers DW, Luft UC, Thews G, Witzleb E. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag, 1968, p. 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Femnou AN, Kuzmiak-Glancy S, Covian R, Giles A, Kay MW, Balaban RS. Intracardiac light catheter for rapid scanning transmural absorbance spectroscopy of perfused myocardium: measurement of myoglobin oxygenation and mitochondria redox state. Am J Physiol Hear Circ Physiol 313: H1199−H1208, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00306.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandjbakhche AH, Bonner RF, Arai AE, Balaban RS. Visible-light photon migration through myocardium in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H698–H704, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrott K, Kuzmiak-Glancy S, Wengrowski A, Zhang H, Rogers J, Kay MW. KATP channel inhibition blunts electromechanical decline during hypoxia in left ventricular working rabbit hearts. J Physiol 595: 3799–3813, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP273873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillis AM, Kulisz E, Mathison HJ. Cardiac electrophysiological variables in blood-perfused and buffer-perfused, isolated, working rabbit heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H784–H789, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glancy B, Willis WT, Chess DJ, Balaban RS. Effect of calcium on the oxidative phosphorylation cascade in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biochemistry 52: 2793–2809, 2013. doi: 10.1021/bi3015983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Gorman MW, Tune JD, Richmond KN, Feigl EO. Feedforward sympathetic coronary vasodilation in exercising dogs. J Appl Physiol 89: 1892–1902, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassinen IE, Hiltunen JK, Takala TES. Reflectance spectrophotometric monitoring of the isolated perfused heart as a method of measuring the oxidation-reduction state of cytochromes and oxygenation of myoglobin. Cardiovasc Res 15: 86–91, 1981. doi: 10.1093/cvr/15.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kariman K, Hempel FG, Jöbsis FF. In vivo comparison of cytochrome aa3 redox state and tissue PO2 in transient anoxia. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 55: 1057–1063, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi K, Neely JR. Control of maximum rates of glycolysis in rat cardiac muscle. Circ Res 44: 166–175, 1979. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.44.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuroda Y, Kawamura T, Suzuki Y, Fujiwara H, Yamamoto K, Saitoh Y. A new, simple method for cold storage of the pancreas using perfluorochemical. Transplantation 46: 457–460, 1988. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198809000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuzmiak-Glancy S, Jaimes R III, Wengrowski AM, Kay MW. Oxygen demand of perfused heart preparations: how electromechanical function and inadequate oxygenation affect physiology and optical measurements. Exp Physiol 100: 603–616, 2015. doi: 10.1113/EP085042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald VW, Winslow RM. Oxygen delivery and myocardial function in rabbit hearts perfused with cell-free hemoglobin. J Appl Physiol 72: 476–483, 1992. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.2.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maillard E, Juszczak MT, Langlois A, Kleiss C, Sencier MC, Bietiger W, Sanchez-Dominguez M, Krafft MP, Johnson PRV, Pinget M, Sigrist S. Perfluorocarbon emulsions prevent hypoxia of pancreatic β-cells. Cell Transplant 21: 657–669, 2012. doi: 10.3727/096368911X593136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makino N, Kanaide H, Yoshimura R, Nakamura M. Myoglobin oxygenation remains constant during the cardiac cycle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 245: H237–H243, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Merkus D, Houweling B, Zarbanoui A, Duncker DJ. Interaction between prostanoids and nitric oxide in regulation of systemic, pulmonary, and coronary vascular tone in exercising swine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1114–H1123, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mootha VK, Arai AE, Balaban RS. Maximum oxidative phosphorylation capacity of the mammalian heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H769–H775, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podesser BK, Hallström S, Schima H, Huber L, Weisser J, Kröner A, Fürst W, Wolner E. The erythrocyte-perfused “working heart” model: hemodynamic and metabolic performance in comparison to crystalloid perfused hearts. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 41: 9–15, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schenkman KA. Cardiac performance as a function of intracellular oxygen tension in buffer-perfused hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H2463–H2472, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schenkman KA, Beard DA, Ciesielski WA, Feigl EO. Comparison of buffer and red blood cell perfusion of guinea pig heart oxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1819–H1825, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00383.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schenkman KA, Marble DR, Burns DH, Feigl EO. Myoglobin oxygen dissociation by multiwavelength spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol 82: 86–92, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segel LD, Ensunsa JL, Boyle WA III. Prolonged support of working rabbit hearts using Fluosol-43 or erythrocyte media. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 252: H349–H359, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segel LD, Rendig SV. Isolated working rat heart perfusion with perfluorochemical emulsion Fluosol-43. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 242: H485–H489, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sloviter HA, Kamimoto T. Erythrocyte substitute for perfusion of brain. Nature 216: 458–460, 1967. doi: 10.1038/216458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spahn DR. Blood substitutes. Artificial oxygen carriers: perfluorocarbon emulsions. Crit Care 3: R93–R97, 1999. doi: 10.1186/cc364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiess BD. Basic mechanisms of gas transport and past research using perfluorocarbons. Diving Hyperb Med 40: 23–28, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40a.Steenbergen C, Deleeuw G, Barlow C, Chance B, Williamson JR. Heterogeneity of the hypoxic state in perfused rat heart. Circ Res 41: 606–615, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamura M, Hazeki O, Nioka S, Chance B. In vivo study of tissue oxygen metabolism using optical and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopies. Annu Rev Physiol 51: 813–834, 1989. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.004121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamura M, Oshino N, Chance B, Silver IA. Optical measurements of intracellular oxygen concentration of rat heart in vitro. Arch Biochem Biophys 191: 8–22, 1978. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42a.von Restorff W, Holtz J, Bassenge E. Exercise induced augmentation of myocardial oxygen extraction in spite of normal coronary dilatory capacity in dogs. Pflugers Arch 372: 181–185, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wengrowski AM, Kuzmiak-Glancy S, Jaimes R III, Kay MW. NADH changes during hypoxia, ischemia, and increased work differ between isolated heart preparations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H529–H537, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00696.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williamson J, Rich T. Mitochondrial function in normal and hypoxic states of the myocardium. In: Advances in Myocardiology, edited by Chazov E, Saks V, Rona G. New York: Springer, 1983, p. 271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson DF, Owen CS, Holian A. Control of mitochondrial respiration: a quantitative evaluation of the roles of cytochrome c and oxygen. Arch Biochem Biophys 182: 749–762, 1977. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90557-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winslow RM. Current status of oxygen carriers (‘blood substitutes’): 2006. Vox Sang 91: 102–110, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winslow RM. Blood substitutes: refocusing an elusive goal. Br J Haematol 111: 387–396, 2000. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wittenberg BA, Wittenberg JB. Oxygen pressure gradients in isolated cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 260: 6548–6554, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Iijima K, Huang J, Walcott GP, Rogers JM. Optical mapping of membrane potential and epicardial deformation in beating hearts. Biophys J 111: 438–451, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]