Abstract

Background:

Patients with endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy are subject to benign tracheal stenosis (TS), for which current therapies are unsatisfactory. We conducted a preliminary investigation of drugs and drug combinations for the prevention and treatment of TS in a rabbit model.

Methods:

Fifty-four rabbits were apportioned into nine groups according to treatment: sham-operated control; untreated TS model; amikacin; budesonide; erythromycin; penicillin; amikacin + budesonide; erythromycin + budesonide; and penicillin + budesonide. TS was induced by abrasion during surgery. The drugs were applied for 7 days before and 10 days after the surgery. Rabbits were killed on the eleventh day. Tracheal specimens were processed for determining alterations in the thicknesses of tracheal epithelium and lamina propria via hematoxylin and eosin. The tracheal mRNA (assessed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction) expressions of the following fibrotic-related factors were determined: transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF- β1), collagen type I (COL1A1), collagen type III (COL3A1), and interleukin-17 (IL-17). The protein levels of TGF-β1, COL1A1, and COL3A1 were determined through immunohistochemistry and integrated optical densities.

Results:

Compared with all other groups, the untreated TS model had significantly thicker tracheal epithelium and lamina propria, and higher mRNA and protein levels of all targeted fibrotic factors. The mRNA and protein levels of the targeted fibrotic factors in all the drug-treated groups were lower than those of the untreated TS model, and differences were most significant in the erythromycin + budesonide group.

Conclusions:

Erythromycin combined with budesonide may reduce inflammation and modify fibrosis progression in TS after tracheal injury.

Keywords: corticosteroid, erythromycin, fibrosis, intubation, tracheal stenosis, tracheostomy

Introduction

Benign tracheal stenosis (TS) remains a difficult problem for the interventional physiologist. TS mainly occurs subsequent to endotracheal intubation (~66%) and tracheostomy (~26%).1–3 Among patients who undergo long-term tracheostomies, 20–64% experience obstructive lesions, the most frequent being tracheal granuloma (58%).4 One study reported that after tracheostomy (mostly indicated by prolonged intubation), 14% and 25% of patients suffered tracheal and subglottic stenosis, respectively.5 Factors that reportedly influence the incidence and development of TS include the timing and mode of mechanical ventilation after intubation,6 mucosal injury by balloon pressure,7 and recurrent respiratory infection.8

Histopathological studies of the thickened tracheal wall of patients with TS after intubation reported finding abnormal collagen deposition, related to myofibroblast activation. The pathological features of benign laryngeal stenosis were fibroblast proliferation and deposition of extracellular matrix, mainly with collagen types I and III.9–11 Many studies have linked interleukin-17 (IL-17), collagen types I and III (COL1A1 and COL3A1), and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) to the pathogenesis of fibrotic disease.

TGF-β is a multifunctional cytokine and an important profibrotic stimulant12,13 that can promote production of collagen protein and deposition of collagen fibers.14 TGF-β has three isoforms that are associated with the healing of wounds. Normal healing of acute wounds occurs in four overlapping phases (hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling), and in the latter two the TGF-β isoforms TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 promote fibrosis, while TGF-β3 suppresses fibrosis.15,16 Compared with normal tracheobronchial tissues, significantly higher levels of TGF-β were present in granulation tissue taken from stenotic trachea (after long-term tracheostomy or prolonged endotracheal intubation).17

Recent studies suggested that in patients with laryngotracheal stenosis, the levels of the proteins of TGF-β, COL1A1, and COL3A1 secreted by tracheal fibroblasts were elevated relative to those of normal controls.18 Studies with mouse models showed that TGF-β inhibitors suppressed fibrosis.19,20 In a rabbit TS model, after circumferential thermal injury, electrocauterization, and re-anastomosis, TGF-β was associated with an increase in submucosal fibrosis by upregulating the protein levels of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF).21

An acknowledged function of IL-17 is mediating inflammation by recruiting neutrophils.22 IL-17A has been associated with the deposition of extracellular matrix by promoting protein levels of TGF-β, IL-6, and collagen, and reducing the degradation of collagen, leading to fibrotic diseases. Studies have confirmed that blocking the IL-17 pathway may be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of fibrotic diseases.23,24 However, the pathogenesis of TS is still not fully clear.

However, there are few studies of drugs for the treatment of TS; most have concerned mitomycin C, and the timing and dosage remain controversial. Erythromycin is a macrolide antibiotic, with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory functions.25 Roxithromycin inhibits the production of TGF-β1 in human glomerular mesangial cells, which may be related to the inhibition of NF-κB p65 protein entering the nucleus.26 Glucocorticoid is an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drug that binds to the glucocorticoid receptor at the cell membrane and enters the nucleus to regulate the transcription of many genes, affecting cellular function. These therapies are not ideal and TS remains a difficult problem. The present study is a preliminary investigation of drugs and drug combinations for the prevention and treatment of TS.

Methods

Experimental design

The present study followed international, national, and institutional guidelines for humane animal treatment and complied with relevant legislation. The experiment was approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University with oversight of the facility in which the studies were conducted (No: 201601001).

Male New Zealand White rabbits (n = 54) were raised by laboratory assistants at the Animal Experiment Center of Guangxi Medical University. At weight 2.0–2.5 kg, the rabbits were equally apportioned to the following nine groups using a random number table, according to the treatment given: sham-operated control; untreated TS model; amikacin (AMK); budesonide (BUD); erythromycin (ERY); penicillin (PEN); AMK combined with BUD (AMK+BUD); ERY combined with BUD (ERY+BUD); and PEN combined with BUD (PEN+BUD).

All drug doses were based on body surface area, calculated with the Meeh–Rubner formula: A = K × (W2/3/104), where A is body surface area, W is weight, and constant K for humans is 10.6 and for rabbits is 10.1.27 Doses for humans were converted to doses for rabbits. Doses for humans were considered as follows: AMK (200 mg/day), BUD (1000 µg/day), ERY (300 mg/day), and PEN (8 × 105 U/day). Drug doses were based on the clinical use in our department.

From 7 days before until 10 days after the surgery for establishing TS (or the sham operation for the control), each of the nine groups were given their respective treatments, twice daily with 6 h between treatments. The treatments of the sham-operated control and untreated TS model groups (vehicle, 0.50 ml/kg saline), and AMK (5 mg/kg in vehicle) and BUD (25 µg/kg in vehicle) were delivered by atomized spray. ERY was fed (7.5 mg/kg). PEN (20,000 U/kg) was delivered by intramuscular injection.

Surgical protocol

TS in the rabbits was established by scraping the tracheal mucosa, as described previously.28 In this study, scrapping of the mucosa and other principal operating procedures were performed by the same operator while blinded to the treatment group. Briefly, each rabbit was anesthetized with an intravenous injection of 3% pentobarbital sodium (1 ml/kg) and placed supine on an operating table. Penicillin sodium was given by intramuscular injection one time to prevent infection. The rabbit’s anterior neck was shaved and disinfected. To enhance analgesia, 2% lidocaine hydrochloride was injected into the anterior neck.

The trachea was clearly exposed with a midline skin incision in the anterior neck. The incision point was located from 1.5 cm to 2 cm cranial to 2 cm caudal of the thyroid cartilage. The trachea was incised transversely along the tracheal cartilage between adjacent tracheal rings, with an incision length two-thirds the circumference of the trachea.

A nylon brush was inserted into the trachea toward the mouth, and then the tracheal mucosa was completely scraped by pushing and pulling the brush before and after, against the left and right walls, about 10 times. Adrenaline gauze was pressed to the wound to stop oozing. The tracheae of the rabbits in the sham-operated control group were not abraded.

Muscle, subcutis, and skin were closed with a continuous suture. On the eleventh day after surgery, the rabbits were anesthetized with an overdose intravenous injection of 3% pentobarbital sodium. They were then killed and the trachea were collected. The excess anesthesia had no effect on experimental results.

Thickness of the epithelium and lamina propria (EPI+LP)

The tracheal specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. The capillaries, fibroblasts, and signs of inflammation in the tissues of each rabbit were observed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

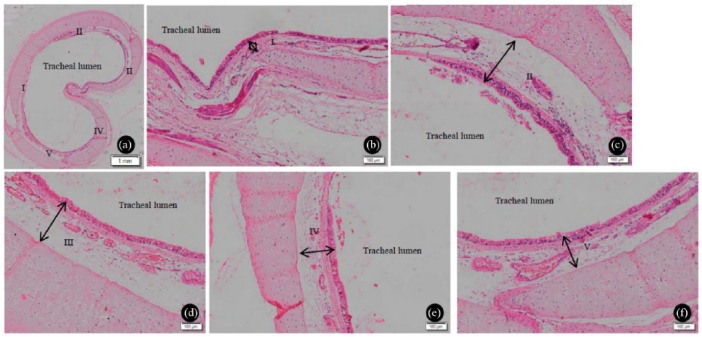

After staining, the trachea was split into five equal segments. The thicknesses of the EPI and LP were measured in accordance with the literature (Figure 1).29 A measurement was taken at the thickest part of each segment. From the medial aspect of the tracheal lumen, the thickness of the EPI+LP was measured from EPI to cartilage.

Figure 1.

Tracheal lamina propria and epithelium of the sham-operated control. (a) The trachea was split into five equal segments, I–V. (b–f) The black double-headed arrows indicate the location of measurement for determining the maximum thickness of the lamina propria and epithelium for the segment. (b) I; (c) II; (d) III; (e) IV; (f) V.

Gene expression analysis of fibrosis-related factors

The total mRNA of each trachea was extracted, and cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PT-PCR) was used to assess the relative values of the mRNAs of the following: TGF-β1; IL-17; COL1A1; COL3A1; and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; as the normalizing reference). The primer sequences are as follows: TGF-β1, 5′- CCCAAGTGATGATGAGGTGC-3′ and 5′-CCTTGCCAAAGAAGCCTGAG-3′; IL-17, 5′-AAGGGAATGAGGACCACCAC-3′ and 5′-CCTACAGCCACCAGCATCTT-3′; COL1A1, 5′-GGACCTCAAGATGTGCCACT-3′ and 5′- CTTGGGGTTCTTGCTGATGT-3′; COL3A1, 5′-TCAAGGCAGAAGGAAACAGC-3′ and 5′-GGGTAGTCTCACAGCCTTGC-3′; GAPDH, 5′-CAAGTGGGGTGATGCTGGT-3′ and 5′-TT-TTGGCTCCGCCCTTC-3′. The primers were designed by and purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and Takara Biomedical Technology (Beijing, China). The relative expression of the gene was quantified by the 2−ΔΔCt method.30

Protein analysis of fibrosis-related factors

TGF-β1, COL1A1, and COL3A1 of the tracheal mucosae were assessed by immunohistochemistry. The tracheal specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. After dewaxing, repairing, and sealing, the slices were incubated serially with TGF-β1 (Abcam), COL1A1 (Novus), and COL3A1 (Novus) antibody. The antibody titers of TGF-β1, COL1A1, and COL3A1 were, respectively, 1:400, 1:1000, and 1:1000. Tissues dyed brown were considered positive. Five fields of view of each slice were randomly selected. The mean density was detected by Image-Pro Plus 6 software and recorded as an integrated optical density (IOD) value. The detailed method was based on the usage of Image-Pro Plus 6.

Statistical analysis

The mean ± standard deviation of the thicknesses of the EPI and LP were calculated for each group. The difference between groups was determined by the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the least significant difference t test or Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 software.

Results

Thickness of tracheal EPI+LP

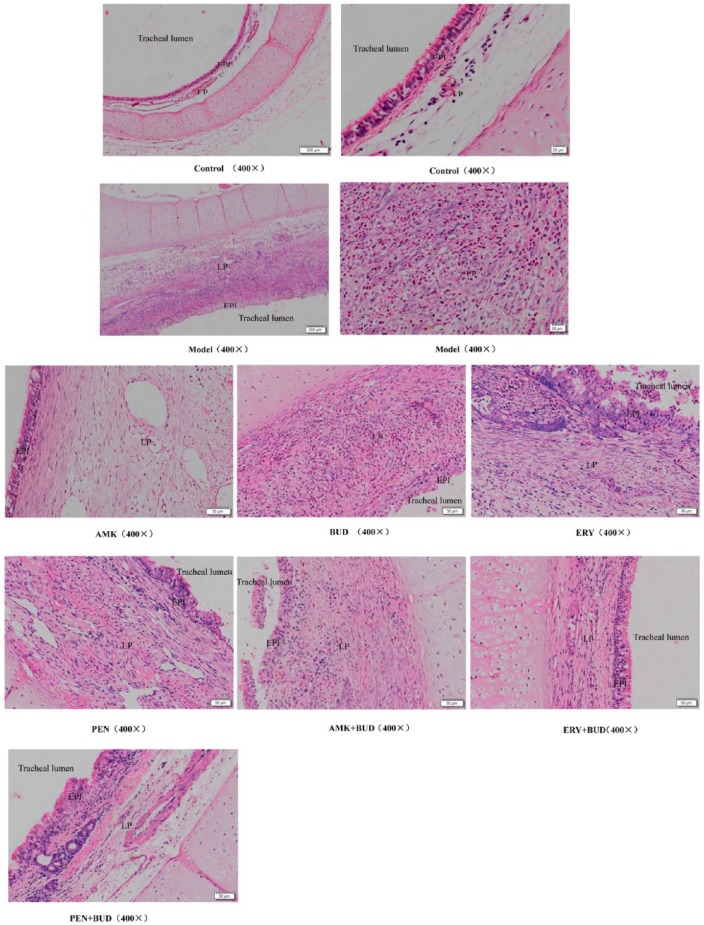

The H&E staining revealed that the thickness of the EPI+LP of the untreated TS model was significantly greater than that of all other groups, confirming that the TS model was successfully established (Table 1; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Targeted characteristics of the tracheal epithelium and lamina propria in the experimental groups: thickness and fibrotic factors.a

| Thickness, mm | TGF-β1 |

COL1A1 |

COL3A1 |

IL-17 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Protein | mRNA | Protein | mRNA | Protein | mRNA | ||

| Controlb | 0.24 ± 0.39 | Reference | 0.50 ± 0.10 | Reference | 0.50 ± 0.10 | Reference | 0.50 ± 0.10 | Reference |

| TS modelc | 1.49 ± 0.28* | 4.82 ± 0.15* | 46.6 ± 0.5* | 4.80 ± 0.15* | 60.8 ± 4.1* | 7.90 ± 0.21* | 79.4 ± 4.7* | 1.57 ± 0.01* |

| AMK | 0.66 ± 0.24 | 3.63 ± 0.06 | 39.5 ± 1.1 | 2.39 ± 0.05 | 24.3 ± 2.8 | 5.00 ± 0.05 | 70.5 ± 3.0 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| ERY | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 1.61 ± 0.02 | 13.3 ± 1.1 | 2.00 ± 0.08 | 3.50 ± 0.20 | 3.68 ± 0.04 | 8.90 ±0.90 | 0.04 ± 0.00 |

| BUD | 0.62 ± 0.11 | 1.85 ± 0.06 | 23.6 ± 2.4 | 1.80 ± 0.03 | 43.7 ± 1.60 | 4.48 ± 0.04 | 60.7 ± 6.6 | 0.05 ± 0.02 |

| PEN | 0.82 ± 0.18 | 2.15 ± 0.04 | 16.9 ± 1.7 | 2.13 ± 0.05 | 12.5 ± 0.10 | 5.33 ± 0.11 | 50.3 ± 4.4 | 0.09 ± 0.00 |

| AMK+BUD | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 2.17 ± 0.03 | 1.70 ± 0.10 | 1.72 ± 0.01 | 15.0 ± 1.90 | 4.87 ± 0.05 | 18.5 ± 4.7 | 0.04 ± 0.00 |

| ERY+BUD | 0.30 ± 0.02** | 1.41 ± 0.01** | 0.80 ± 0.10** | 1.64 ± 0.02** | 0.40 ± 0.50** | 3.05 ± 0.01** | 3.8 ± 2.1** | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| PEN+BUD | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 1.71 ± 0.02 | 1.80 ± 0.20 | 1.70 ± 0.02 | 7.40 ± 2.70 | 4.79 ± 0.04 | 25.6 ± 5.8 | 0.03 ± 0.00 |

Levels of mRNA are relative to the sham-operated control group; protein mean density is reported as ×10−3; bsham-operated control, not given a drug treatment; cTS model, not given a drug treatment; *versus control group, p < 0.05; ** versus other drugs intervention group, p < 0.05.

AMK, amikacin; BUD, budesonide; ERY, erythromycin; PEN, penicillin; TS, tracheal stenosis.

Figure 2.

Epithelium and lamina propria in the tracheal lumen of all groups; hematoxylin and eosin staining.

AMK, amikacin; BUD, budesonide; EPI, epithelium; ERY, erythromycin; LP, lamina propria; PEN, penicillin.

The H&E also showed that the cells of the EPI+LP in the sham-operated control group were orderly, and the boundary between these structures was clearly observed. However, in the TS model, the cells of these structures were disorderly, and the boundary between them was obscure. Furthermore, in the model group there were signs of angiogenesis, fibroblasts, and inflammatory cells. The majority of inflammatory cells were eosinophils. The structures and boundaries of the EPI and LP in the drug combination groups were clearer than in the single drug groups; also, compared with the single drug groups, the angiogenesis, fibroblasts, and inflammatory cells in the drug combination groups were significantly reduced (Figure 2).

The thicknesses of the tracheal EPI+LP in the control and ERY+BUD groups were statistically similar (p = 0.07; Table 1). The thicknesses in the AMK, BUD, and PEN groups were comparable, but all were significantly greater than those of the control and ERY+BUD groups, and also significantly greater than those of the ERY group. The thickness in the ERY+BUD group was also significantly lower than that of the AMK+BUD or PEN+BUD groups (p = 0.009, each).

Factors associated with fibrosis

This study determined the normalized mRNA expressions of the following factors that have been positively associated with the degree of tracheal fibrosis in the EPI+LP: TGF-β1, COL1A1, COL3A1, and IL-17 (Table 1). In the untreated TS model group, the normalized mRNA expressions of TGF-β1, COL1A1, COL3A1, and IL-17 were all significantly higher than those of the sham-operated control (p = 0.003, 0.013, 0.007, and 0.002, respectively; Table 1).

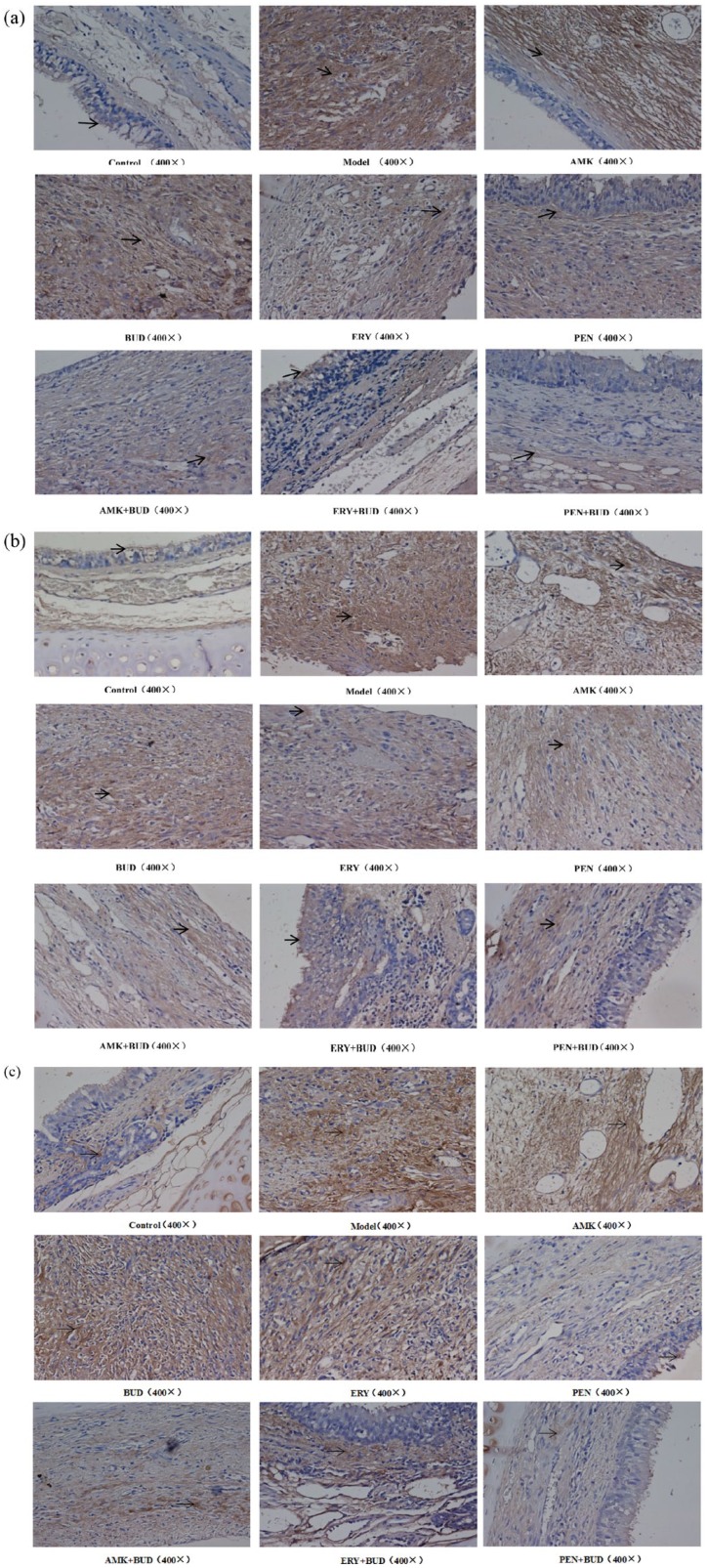

The proteins TGF-β1, COL1A1, and COL3A1 were found in the EPI+LP, but primarily in the LP, and specifically in the cytoplasm of the mucosa epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells. In the TS model group, the mean densities of the proteins TGF-β1, COL1A1, and COL3A1 were all significantly higher than that of the control group (Table 1; Figure 3), while the mean densities of all these proteins in the TS model were higher than that of the corresponding proteins in the drug-treated groups (Figure 3; as specified below).

Figure 3.

Staining results of fibrosis-related proteins in all groups. (a) TGF-β1; (b) COL1A1; (c) COL3A1 (400×).

AMK, amikacin; BUD, budesonide; ERY, erythromycin; PEN, penicillin.

TGF-β1 mRNA and protein levels

The normalized TGF-β1 mRNA expression in the untreated TS model was significantly higher than that of any group treated with any drug or drug combination (Table 1). The TGF-β1 mRNA expression of the AMK group was significantly higher than that of any of the other drug-treated groups, and that of the AMK+BUD group was significantly higher than that of the other combination-drug groups. Among the groups treated with a single drug, the TGF-β1 mRNA expression of the ERY group was significantly lower than that of the AMK (p = 0.001) or PEN (p = 0.006) groups, but comparable to the BUD (p = 0.105) group. Among the groups treated with a drug combination, the TGF-β1 mRNA expression of the ERY+BUD group was significantly lower than that of the AMK+BUD (p = 0.001) or PEN+BUD (p < 0.001) groups.

The TGF-β1 protein mean density of any group treated with a single drug was significantly higher than that of any group treated with a drug combination (Table 1; Figure 3(a)). Among the groups treated with a single drug, the TGF-β1 mean density of the AMK group was significantly higher than that of the BUD (p = 0.022), ERY (p < 0.001), and PEN (p = 0.001) groups, which were comparable, although the ERY group was lowest. Among the groups treated with a drug combination, the TGF-β1 mean density of the ERY+BUD group was significantly lower than that of either the AMK+BUD (p = 0.017) or PEN+BUD (p = 0.029) groups.

COL1A1 mRNA and protein levels

The normalized mRNA expression of COL1A1 in the untreated TS model was significantly higher than that of any of the drug-treated groups (Table 1). The mRNA expression of COL1A1 in any of the groups treated with a single drug was higher than that of any group treated with a drug combination. Among the groups treated with a single drug, the mRNA expressions of COL1A1 in the AMK, ERY, or PEN groups were statistically similar, with AMK being the highest; BUD was significantly lower than that of the others. Among the groups treated with a drug combination, the mRNA expressions of COL1A1 in the AMK+BUD and PEN+BUD were similar (p = 1.000), while that of the ERY+BUD group was significantly lower than either of these.

Among the groups treated with a single drug, the COL1A1 mean density of the BUD group was significantly higher than that of the AMK (p = 0.004), which was significantly higher than that of the ERY (p = 0.002; Table 1; Figure 3(b)). The COL1A1 mean density of the PEN, PEN+BUD, and AMK+BUD groups were comparable. The COL1A1 mean density of the ERY+BUD group was significantly lower than that of the AMK+BUD (p < 0.001) or PEN+BUD (p < 0.001) groups.

COL3A1 mRNA and protein levels

The mRNA expression of COL3A1 in the untreated TS model was significantly higher than that of any of the drug-treated groups (Table 1). Among the groups treated with a single drug, the normalized mRNA COL3A1 expressions in the AMK and PEN groups were similar (p = 0.731), while that of the ERY group was significantly lower than in any of the others (Table 1). Among the groups treated with a drug combination, the mRNA COL3A1 expressions in the AMK+BUD and PEN+BUD groups were similar (p = 0.455), while that of the ERY+BUD group was significantly lower than in any of the others.

Among the groups treated with a single drug, the mean density of COL3A1 of the ERY group was significantly lower than that of any of the others (Table 1; Figure 3(c)). Among the groups treated with a drug combination, the mean density of COL3A1 of the ERY+BUD group was significantly lower than that of the AMK+BUD (p < 0.001) or PEN+BUD (p < 0.001) groups.

IL-17 mRNA expression

The mRNA expression of IL-17 in the untreated TS model was significantly higher than that of any of the drug-treated groups, which were all statistically similar (Table 1). Among the groups treated with a single drug, the IL-17 mRNA expression was highest in the PEN group and lowest in the ERY group. Among the groups treated with a drug combination, the IL-17 mRNA expression was lowest in the ERY+BUD group.

Discussion

This was a preliminary investigation of the comparative protective effects against TS of the drugs AMK, ERY, PEN, or BUD, or of AMK, ERY, or PEN combined with BUD. The drug treatments were administered to rabbits from 7 days before until 10 days after tracheal abrasion was performed to induce a model of TS. H&E staining of tracheal segments on the eleventh day after surgery revealed that the EPI+LP of the TS model was significantly thicker than that of the sham-operated control. This showed that the TS model was successfully established. Furthermore, the significantly greater mRNA expressions and protein levels (i.e. mean density) of factors related to fibrosis in the trachea of the untreated TS model group compared with the sham-operated control confirmed an association between these factors and the thickness of the EPI+LP caused by tracheal injury. The major finding of this study is that the thickness of the tracheal EPI+LP in the rabbits treated with ERY+BUD, but not in the other drug-treated groups, was statistically comparable to that of the sham-operated control. Furthermore, the mRNA expressions and protein levels of each of the fibrotic factors TGF-β1, COL1A1, and COL3A1 were significantly lower in the ERY+BUD group compared with any of the other drug treatments. This strongly suggests that the combined treatment with ERY and BUD was protective against abrasion-induced tracheal fibrosis, and may be a potential clinical treatment in TS.

The treatment of TS remains a difficult problem. Tracheal resection and end-to end anastomosis (TRE) is the standard surgical treatment of TS, and is suitable for young patients.31 However, TRE is not suitable for patients with long airway stenosis, subglottic stenosis, concomitant infection, or cardiopulmonary insufficiency,32,33 and the restenosis rate is reportedly 12.4%.34 Methods of interventional bronchoscopy have been used to treat TS, including CO2 laser/cryotherapy, ballooning, bouginage, Nd:YAG (neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) laser resection, and stent insertion. The short-term effect is obvious and the success rate is 87%.1 In recent studies, a tracheal transplantation model in rabbits has also been used to treat TS, but the degradation of transplanted material remained a difficult problem.35 Thus, both surgical treatment and interventional bronchoscopy are associated with bodily damage that may lead to restenosis of the airway.

Medication to prevent or treat TS may avoid the secondary damage caused by to surgical treatment or interventional bronchoscopy. Currently, such medicines consist of mitomycin C,36 paclitaxel,37 glucocorticoids, 5-fluorouracil,38 and scar inhibitors. The dosage is controversial for mitomycin C. While mitomycin C is applied for stenosis caused by acute injury, it may not be effective for a chronic condition, and is best applied before the trachea is damaged.39,40

BUD has been used as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of TS. When combined with interventional bronchoscopy, BUD effectively inhibited the proliferation of granuloma.41,42 In a child with granuloma after tracheotomy, intravenous infusion of dexamethasone or YAG laser ablation could relieve the symptoms of tracheal obstruction symptoms. The granuloma did not re-proliferate after YAG laser ablation combined with BUD inhalation and tranilast.41

ERY is a macrolide antibiotic with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory functions, and which inhibits fibroblast proliferation and the secretion of fibrosis-related factors.43 Park and colleagues44 found that ERY treatment was associated with lower mRNA expressions of COL1A1 and COL3A1 in fibroblasts derived from nasal polyps stimulated to differentiate with TGF-β.

It has been reported that the presence of bacterial biofilms, bacterial counts, as well as TGF-β1 protein levels are associated with the pathogenesis of benign TS,45 and antibiotics may help prevent TS after tracheal injury.39 PEN is a β-lactam antibiotic with high efficiency, low toxicity, and wide clinical application.

In the present preliminary study, we found that in the groups treated with AMK, BUD, ERY, or PEN, after tracheal mucosa injury the mRNA expressions of TGF-β1, COL1A1, COL3A1, and IL-17 were lower than in the untreated TS model group, and the maximal thicknesses of the EPI+LP were similarly less. The association between TGF-β1, COL1A1, COL3A1, and IL-17 with the thickness of the EPI+LP in response to airway injury indicates that these fibrotic factors have pathogenic roles in TS as well as specifically fibrosis. Because these signs of TS were significantly reduced in the drug-treated groups compared with the untreated model, we conclude that these drug treatments may be preventive in TS.

In addition, among the groups treated with a single drug, the effect of ERY was more significant than that of AMK, BUD, or PEN. In the groups treated with any drug combination (AMK+BUD, ERY+BUD, and PEN+BUD), the degree of tracheal fibrosis was less than that of any group treated with a single drug, and inhibition of stenosis was most obvious in the group treated with ERY+BUD. Thus, ERY+BUD may be considered a potential therapy for the treatment of TS. Our results warrant study of the long-term effects of these drugs in preventing or lessening TS, and investigations to determine dosage and complications.

In our research, we discovered that stenosis was not related to the membranous wall, which consists of muscle and elastic. Clinically, stenosis in patients after prolonged intubation and post-tracheostomy is not due to changes in the tracheal membranous wall. There is no research to investigate the reason for this.

In the present research, we regret that observations of the long-term efficacy of drugs were not an objective.

In summary, our study showed that AMK, BUD, ERY, or PEN could somewhat reduce the degree of tracheal fibrosis after tracheal injury, although the effect of using a single drug was not very satisfactory. The combination of ERY and BUD was the best preventive of the fibrotic process. Furthermore, levels of TGF-β1, COL1A1, COL3A1, and IL-17 were associated with pathogenesis, and the downregulation of these factors could be considered a goal to reduce inflammation and modify fibrosis.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Funds of China (81760001).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Qin Enyuan  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8494-4831

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8494-4831

Contributor Information

Qin Enyuan, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Xu Mingpeng, Fourth People’s Hospital of Nanning, Nanning, China.

Gan Luoman, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Gan Jinghua, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Li Yu, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Li Wentao, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Hou Changchun, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Li Lihua, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Liuzhou, China.

Meng Xiaoyan, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Zhou Lei, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Liu Guangnan, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, 530007, China.

References

- 1. Rahman NA, Fruchter O, Shitrit D, et al. Flexible bronchoscopic management of benign tracheal stenosis: long term follow-up of 115 patients. J Cardiothorac Surg 2010; 5: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thornton RH, Gordon RL, Kerlan RK, et al. Outcomes of tracheobronchial stent placement for benign disease. Radiology 2006; 240: 273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Povedano AC, Cabrera LM, Povedano FJC, et al. Endoscopic treatment of central airway stenosis: five years’ experience. Arch Bronconeumol 2005; 41: 322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bagley PH, O’Shea M. Increased frequency of obstructive airway abnormalities with long-term tracheostomy. Chest 1993; 104: 136–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elanwar MW, Nofal AF, Shawadfy MAE, et al. Tracheostomy in the intensive care unit: a university hospital in a developing country study. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017; 21: 33–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller TL, Zhu Y, Altman AR, et al. Sequential alterations of tracheal mechanical properties in the neonatal lamb: effect of mechanical ventilation. Pediatr Pulmonol 2007; 42: 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rumbak MJ, Walsh FW, Anderson WM, et al. Significant tracheal obstruction causing failure to wean in patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: a forgotten complication of long-term mechanical ventilation. Chest 1999; 115: 1092–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mazhar K, Gunawardana M, Webster P, et al. Bacterial biofilms and increased bacterial counts are associated with airway stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 150: 834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Correa Reis JG, Takiya CM, Lima Carvalho A, et al. Myofibroblast persistence and collagen type I accumulation in the human stenotic trachea. Head Neck 2012; 34: 1283–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu H, Chen JC, Holinger LD, et al. Histopathologic fundamentals of acquired laryngeal stenosis. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med 1995; 15: 655–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pokharel RP, Maeda K, Yamamoto T, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in exuberant tracheal granulation tissue in children. J Pathol 1999; 188: 82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moir LM, Burgess JK, Black JL. Transforming growth factor beta 1 increases fibronectin deposition through integrin receptor alpha 5 beta 1 on human airway smooth muscle. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 121: 1034–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Secker GA, Shortt AJ, Sampson E, et al. TGFbeta stimulated re-epithelialisation is regulated by CTGF and Ras/MEK/ERK signalling. Exp Cell Res 2008; 314: 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Varga J, Rosenbloom J, Jimenez SA. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF beta) causes a persistent increase in steady-state amounts of type I and type III collagen and fibronectin mRNAs in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Biochem J 1987; 247: 597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diegelmann RF, Evans MC. Wound healing: an overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Front Biosci 2004; 9: 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Elicora A, Liman ST, Yegin BA, et al. Effect of locally applied transforming growth factor beta3 on wound healing and stenosis development in tracheal surgery. Respir Care 2014; 59: 1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee YC, Hung MH, Liu LY, et al. The roles of transforming growth factor-beta(1) and vascular endothelial growth factor in the tracheal granulation formation. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2011; 24: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Motz K, Samad I, Yin LX, et al. Interferon-gamma treatment of human laryngotracheal stenosis-derived fibroblasts. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017; 143: 1134–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murillo-Cuesta S, Rodriguez-de la, Rosa L, Contreras J, et al. Transforming growth factor beta1 inhibition protects from noise-induced hearing loss. Front Aging Neurosci 2015; 7: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arribillaga L, Dotor J, Basagoiti M, et al. Therapeutic effect of a peptide inhibitor of TGF-β on pulmonary fibrosis. Cytokine 2011; 53: 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Antón-Pacheco JL, Usategui A, Martínez I, et al. TGF-β antagonist attenuates fibrosis but not luminal narrowing in experimental tracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope 2016; 127: 561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beringer A, Noack M, Miossec P. IL-17 in chronic inflammation: from discovery to targeting. Trends Mol Med 2016; 22: 230–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang S, Huang D, Weng J, et al. Neutralization of interleukin-17 attenuates cholestatic liver fibrosis in mice. Scand J Immunol 2016; 83: 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fu XX, Zhao N, Dong Q, et al. Interleukin-17A contributes to the development of post-operative atrial fibrillation by regulating inflammation and fibrosis in rats with sterile pericarditis. Int J Mol Med 2015; 36: 83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Macrolides beyond the conventional antimicrobials: a class of potent immunomodulators. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008; 31: 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamabe H, Shimada M, Kaizuka M, et al. Roxithromycin inhibits transforming growth factor-beta production by cultured human mesangial cells. Nephrology (Carlton) 2006; 11: 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spiers DE, Candas V. Relationship of skin surface area to body mass in the immature rat: a reexamination. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1984; 56: 240–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakagishi Y, Morimoto Y, Fujita M, et al. Rabbit model of airway stenosis induced by scraping of the tracheal mucosa. Laryngoscope 2005; 115: 1087–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hillel AT, Namba D, Ding D, et al. An in situ, in vivo murine model for the study of laryngotracheal stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 140: 961–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rao X, Huang X, Zhou Z, et al. An improvement of the 2ˆ(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinforma Biomath 2013; 3: 71–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ahn HY, Su Cho J, Kim YD, et al. Surgical outcomes of post intubational or post tracheostomy tracheal stenosis: report of 18 cases in single institution. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 21: 14–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsakiridis K, Darwiche K, Visouli AN, et al. Management of complex benign post-tracheostomy tracheal stenosis with bronchoscopic insertion of silicon tracheal stents, in patients with failed or contraindicated surgical reconstruction of trachea. J Thorac Dis 2012; 4: 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Puma F, Ragusa M, Avenia N, et al. The role of silicone stents in the treatment of cicatricial tracheal stenoses. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 120: 1064–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jeong BH, Um SW, Suh GY, et al. Results of interventional bronchoscopy in the management of postoperative tracheobronchial stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012; 144: 217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ghorbani F, Moradi L, Shadmehr MB, et al. In-vivo characterization of a 3D hybrid scaffold based on PCL/decellularized aorta for tracheal tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2017; 81: 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Palinko D, Matievics V, Szegesdi I, et al. Minimally invasive endoscopic treatment for pediatric combined high grade stenosis as a laryngeal manifestation of epidermolysis bullosa. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017; 92: 126–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qiu XJ, Zhang J, Wang J, et al. Application of paclitaxel as adjuvant treatment for benign cicatricial airway stenosis. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci 2016; 36: 817–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mao X, Cheng X, Zhang Z, et al. The therapy with ethosomes containing 5-fluorouracil for laryngotracheal stenosis in rabbit models. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017; 274: 1919–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith ME, Elstad M. Mitomycin C and the endoscopic treatment of laryngotracheal stenosis: are two applications better than one? Laryngoscope 2009; 119: 272–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Teo F, Anantham D, Feller-Kopman D, et al. Bronchoscopic management of sarcoidosis related bronchial stenosis with adjunctive topical mitomycin C. Ann Thorac Surg 2010; 89: 2005–2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Okuda N, Nakataki E, Itagaki T, et al. Complete bronchial obstruction by granuloma in a paediatric patient with translaryngeal endotracheal tube: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8: 260–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yokoi A, Nakao M, Bitoh Y, et al. Treatment of postoperative tracheal granulation tissue with inhaled budesonide in congenital tracheal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg 2014; 49: 293–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amsden GW. Anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides: an underappreciated benefit in the treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infections and chronic inflammatory pulmonary conditions? J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 55: 10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Park HH, Park IH, Cho JS, et al. The effect of macrolides on myofibroblast differentiation and collagen production in nasal polyp-derived fibroblasts. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2010; 24: 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mazhar K, Gunawardana M, Webster P, et al. Bacterial biofilms and increased bacterial counts are associated with airway stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 150: 834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]