Abstract

Background:

Integrated palliative care aims at improving coordination of palliative care services around patients’ anticipated needs. However, international comparisons of how integrated palliative care is implemented across four key domains of integrated care (content of care, patient flow, information logistics and availability of (human) resources and material) are lacking.

Aim:

To examine how integrated palliative care takes shape in practice across abovementioned key domains within several integrated palliative care initiatives in Europe.

Design:

Qualitative group interview design.

Setting/participants:

A total of 19 group interviews were conducted (2 in Belgium, 4 in the Netherlands, 4 in the United Kingdom, 4 in Germany and 5 in Hungary) with 142 healthcare professionals from several integrated palliative care initiatives in five European countries. The majority were nurses (n = 66; 46%) and physicians (n = 50; 35%).

Results:

The dominant strategy for fostering integrated palliative care is building core teams of palliative care specialists and extended professional networks based on personal relationships, shared norms, values and mutual trust, rather than developing standardised information exchange and referral pathways. Providing integrated palliative care with healthcare professionals in the wider professional community appears difficult, as a shared proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach is lacking, and healthcare professionals often do not know palliative care professionals or services.

Conclusion:

Achieving better palliative care integration into regular healthcare and convincing the wider professional community is a difficult task that will take time and effort. Enhancing standardisation of palliative care into education, referral pathways and guidelines and standardised information exchange may be necessary. External authority (policy makers, insurance companies and professional bodies) may be needed to support integrated palliative care practices across settings.

Keywords: Delivery of healthcare, integrated, inter-professional relations, qualitative research, palliative care

What is already known about the topic?

Although integrated palliative care aims at improving coordination of palliative care services around patients’ anticipated needs, there is limited evidence about which integrated palliative care models could lead to optimal palliative care.

In order to promote integrated care, four key domains of the care delivery process need to be well organised (content of care, patient flow, information logistics and availability of (human) resources and material).

Palliative care literature describes these key domains only to a limited extent, for example, by referring to studies on the development of referral criteria to promote early integration as well as by the identification of indicators and elements important for palliative care integration into oncology and chronic care.

What this paper adds?

This paper suggests that the dominant strategy for fostering integrated palliative care is building core teams of palliative care specialists and extended professional networks, rather than developing standardised information exchange and referral pathways.

Although this seems a strength, integration still remains fragile due to its informal nature based on mutual trust and sharing values as well as its limited scope.

Therefore, integrated palliative care provision beyond extended professional networks, where healthcare professionals do not share a proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach and do not know palliative care professionals, is jeopardised.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

In order to promote better integration in regular healthcare, convincing the wider community is needed, but this is a difficult task that will take time and effort.

Standardisation of palliative care into education, referral pathways, protocols and guidelines and standardised information exchange may need to be enhanced.

Building evidence for the importance of delivering high-quality palliative care together with influence from external authorities, such as policy makers, insurance companies and professional bodies may be needed.

Introduction

Fragmentation of healthcare services and late referrals to palliative care prevent many patients from receiving the palliative care they need at the right time and in the right place.1,2 Therefore, many patients have unmet palliative care needs,3 experience undesired hospital admissions in the last weeks of life4 or are not able to die at their preferred place.5 Several studies have suggested that integrated palliative care (IPC) leads to better results in terms of quality of life, costs and even survival.6–8 IPC aims at improving coordination of palliative care around patients’ anticipated needs9,10 and can be defined as: ‘bringing together administrative, organisational, clinical and service aspects of palliative care in order to achieve continuity of care between all actors involved in the care network of patients receiving palliative care’.10

However, IPC is not easily achieved. Roles and responsibilities of generalist (professionals who are primary responsible for the patient) and specialist palliative care professionals are not always clear.11,12 Moreover, some generalist professionals fear that they find themselves taking the backseat in the care of their patients.11,12 Other challenges include lack of clarity about the level of expertise needed for palliative care and uncertain illness trajectories (especially regarding non-cancer diagnoses) that make it difficult to know the best timing to involve palliative care professionals.11,12 There is limited evidence from palliative care literature about which IPC models could lead to optimal palliative care.13 For this reason, it may be useful to turn to the growing body of evidence of integrated care in chronic illnesses. An extensive body of literature in integrated chronic care14–16 is available suggesting that in order to promote integrated care, four key domains of the care delivery process need to be well organised: (1) content of care – ensuring that patients receive the right care, (2) patient flow – ensuring that the right patients receive care at the right time from the right healthcare professional (HCP), (3) information logistics – ensuring that the right information is available at the right time and (4) availability of (human) resources and material – ensuring that the right HCP and the right medication and equipment are available at the right time.

Current palliative care literature describes some aspects of the abovementioned key domains. For example, patient flow was investigated in studies which developed referral criteria to promote early palliative care integration.17,18 Hui et al.19 described aspects of content of care by identifying indicators for the integration of palliative care in oncology (i.e. interdisciplinary teamwork, routine symptom screening, advance care planning and educational activities). Siouta et al.20 found similar results in their review of empirically tested IPC models in cancer and chronic diseases. However, literature21,22 also suggests that availability of (human) resources is often insufficient to enable widespread integration of palliative care. Although these studies could contribute to promoting IPC, international comparisons of how IPC is implemented across these four domains are lacking. Therefore, this article focuses on how IPC takes shape in practice across the four key domains of integrated care within several IPC initiatives in five European countries.

Methods

This study used a qualitative group interview design. Group interviews enable participants to interact and complement each other’s answers. Therefore, compared to individual interviews, group interviews can provide a broader spectrum of data including various insights in a particular phenomenon.23

Recruitment

This study was part of a multiple embedded case study conducted by the European InSup-C project that aimed to identify prerequisites for successful IPC.24 A total of 23 IPC initiatives were selected based on inclusion criteria described elsewhere.24 In order to select participants for the group interviews, we requested contact persons of the initiatives to indicate HCPs that were part of the initiative. In order to include outsider perspectives as well, invitation lists also included HCPs who cared for patients receiving care from the initiative but were not directly involved in the initiative. Therefore, we asked patients who had been recruited from the initiatives for an interview study24 for their consent to contact HCPs in their care networks for participation in a group interview. Invitation lists included a large number of HCPs per initiative (range: 15–25) in order to achieve a number of 6–10 participants per group interview. Participants were invited by e-mail.

Data collection

Group interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview protocol. The interview protocol was based on the four predefined key domains (content of care, patient flow, information logistics and availability of (human) resources and material) and included open and probing questions. A preliminary interview protocol was discussed and approved within the international research team and was pilot tested in the United Kingdom and in Germany. Findings from the two pilots were discussed within the international research team resulting in a final interview protocol (Supplementary file). This procedure ensured a uniform group interview procedure across countries, irrespective of language or culture group. Participants provided verbal consent before starting each group interview. Group interviews lasted on average of 90 min (range: 1–2 h) were mainly held at the initiatives’ locations and were facilitated and observed by two researchers from each national research team with experience in qualitative research and/or palliative care. Group interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were collected between May 2015 and January 2016.

Review committee approvals were obtained in all participating countries.25 In the Netherlands, the study did not fall within the remit of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act and was therefore waived for further screening by the ethics committee.

Data analysis

In order to enable uniform analysis of international data, the Dutch research team analysed the group interview transcripts from all countries. Transcripts that were not written in Dutch or English were translated into English by professional translators. Group interview transcripts were analysed using a deductive content analysis approach.26 This approach allowed us to examine how IPC takes shape in practice by building on already existing theory on integrated chronic care.

First, three researchers from the Dutch research team read all group interviews in order to become familiar with the data. In order to provide the Dutch research team with the required contextual knowledge to draw accurate interpretations from the international data, face-to-face and Skype discussions were held with national research teams in order to clarify health systems characteristics and particular national topics. Subsequently, one researcher deductively analysed the group interviews using the four key domains from the interview protocol as sensitising concepts to identify relevant themes. Identified themes were discussed within the Dutch research team until consensus was reached. In order to check validity of the themes and interpretations, these were peer reviewed by the international research team.

The analysis was supported by qualitative data software ATLAS.ti 7.1. Due to the complex international context, the authors anticipated it would be difficult to organise a member check with the original group interview participants. Therefore, we did not include a member check. However, the Dutch team frequently consulted the national research teams during international project team meetings. To report on the data collection and analysis methods, we used the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist.27

Results

A total of 19 group interviews were conducted: 2 in Belgium, 4 in the Netherlands, 4 in the United Kingdom, 4 in Germany and 5 in Hungary. Four initiatives did not participate due to lack of time or inability to further cooperate in the study. Initiatives involved specialised or general palliative care services based at various settings (home, hospital, hospice and nursing home; Table 1). Although all initiatives aimed to provide IPC for patients with both cancer and chronic diseases, the majority of patients had cancer. In total, 142 participants attended the group interviews of which the majority were nurses (n = 66; 46%) and physicians (n = 50; 35%; Table 2). Other participants included an occupational therapist, pharmacists, physiotherapists, psychologists, social workers and spiritual caregivers. Themes we identified for each of the four key domains are presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of integrated palliative care initiatives in the study.

| Type of initiativea | Setting in which initiative was

originated |

Diagnostic groups served in initiative (COPD/heart failure/cancer) | Initiative IDs (country + initiative number) | Example of an integrated palliative care initiative in this category | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | Hospital | Hospice | Nursing home | ||||

| Specialised palliative care support service | X | All, mainly cancer | B1, B3 | Secondary specialised palliative team providing consultation and palliative home care on request to regional hospitals, palliative care units, regional nursing homes, home care and replacement home environments | |||

| Specialised palliative care service in conjunction with specialised palliative home care services and/or other primary and secondary care services | X | All, mainly cancer | G1, G2, G3, G4, NL5, HU1 | Collaboration between specialised palliative care unit at (academic) hospital and specialised palliative home care team providing palliative care at home and coordinating several services in the community | |||

| Specialised palliative care service in conjunction with primary and secondary care | X | All, mainly cancer | UK1, UK3, UK5, HU4 | Collaboration between inpatient hospice providing day therapy and several services in the community such as hospitals, GP practice, nursing services, ambulance services, nursing/residential care homes | |||

| General palliative care service in conjunction with specialised palliative care (support) service | X | All, mainly cancer | B2, UK2, NL4, HU2, HU3 | General home care service providing palliative care at home with the support of a regional specialist palliative care team | |||

| General palliative care nursing home service in conjunction with secondary care | X | X | COPD | NL2 | Inpatient COPD nursing and rehabilitation ward located at a regional hospital providing palliative care and preparing patients to live at home | ||

| General palliative care service in conjunction with primary care | X | All, mainly cancer | NL3, HU5 | Multidisciplinary oncology unit at a regional hospital collaborating with specialised palliative care case managers who coordinate palliative care in the community | |||

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GP: general practitioner.

Specialised means that the majority of healthcare professionals involved in the initiatives are palliative care specialists, while general means that of the healthcare professionals involved in the initiative, only a few are palliative care specialist or have received basic palliative care training.

Table 2.

Participants who attended group interviews.

| Profession | N |

|---|---|

| Nursea | 66 |

| Physicianb | 50 |

| Physiotherapist | 6 |

| Psychologist | 6 |

| Social worker | 6 |

| Spiritual caregiver | 4 |

| Pharmacist | 2 |

| Occupational therapist | 1 |

| Other | 1 |

| Total | 142 |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GP: general practitioner.

Mainly includes home care nurses, specialised nurses or nurse specialists in, for example, COPD, heart failure, oncology and palliative care.

Mainly includes GPs, palliative care specialists and some cardiologists, pulmonologists, internists, pain specialists and geriatricians.

Table 3.

Key domains and corresponding themes.

| Key domains | Themes |

|---|---|

| Content of care | Sharing a proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach within the core team, extended professional network and wider professional community |

| Patient flow | The influence of available palliative care knowledge and informal professional relationships on palliative care referrals and hospital discharges |

| Information logistics | Variations in quality of information transfer and standardisation within core team, extended professional network and wider professional community |

| Availability of (human) resources and material | Solutions for availability of trained staff and medication during out-of-hours |

Content of care

Ensuring that patients receive the right care is based on whether HCPs share a proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach. This approach includes anticipatory holistic assessment of patient’s current and future needs and wishes as well as multidisciplinary collaboration between all professionals involved in the patient’s care:

[…] you try to think anticipatory […]: ‘Well, we’ve got this scenario, we can expect that and this has consequences for care provision’ […] You try to integrate this element [of] ‘multidisciplinary anticipatory thinking’. (NL4)

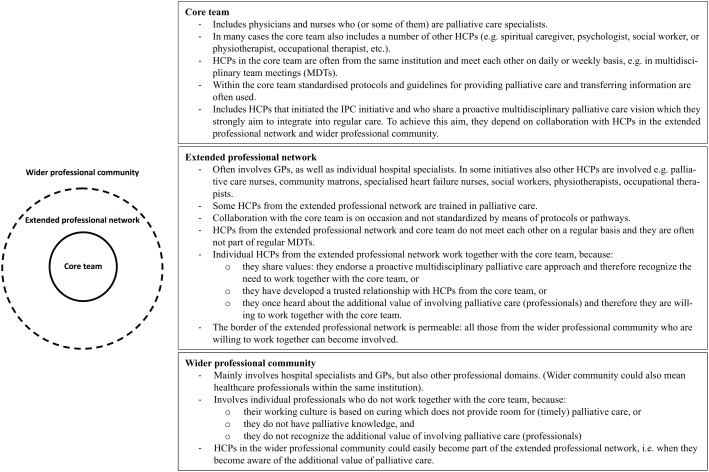

Most initiatives seem to consist of a core team, an extended professional network (hereafter extended network) and a wider professional community (hereafter wider community; Figure 1). The core team generally consists of HCPs who share a proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach. Core team members meet each other regularly, for example, during multidisciplinary meetings (MDTs), discuss patients’ multidimensional needs and make joint care plans:

At onco-team meetings we discuss the patients’ further treatments and care. In my opinion, it works very well for us. (Pulmonologist 2: HU1)

Figure 1.

Illustration and explanation of the core team, extended professional network and wider professional community.

HCPs from the core team have strong informal ties with HCPs in the extended network who also share a proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach but are not actively involved in the core team. Although HCPs in the extended network meet core team members less frequently, they report good collaboration for providing IPC:

As a family doctor […] I feel even more integrated, even though I am not always here at the [multidisciplinary team] discussions. […] I experience it as a positive togetherness that since [integrated palliative care initiative] started, as far as I can recall, there haven’t been any patients who were taken to hospital for a short period of time and died, but everything happened at home in absolute peace and with really perfect organisation. (G2)

However, participants report difficulties providing IPC when it concerns HCPs in the wider community. We are here together with […] a selected group of [palliative care] people […]. There are, well, many colleagues whom I think are poorer with regard to providing [palliative] care. (NL3). HCPs in the wider community seem not to share a proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach but often adopt a culture focussing on the medical and curative aspects of care. Participants therefore report insufficient collaboration with HCPs in the wider community, resulting in a lack of continuity of care:

And so that’s our biggest challenge, […] that all of us – and that means across all of the different health settings – all have to take a responsibility to work together. And that’s really difficult because we don’t even see each other, let alone talk to each other, and we inhabit different cultures. (UK1)

Sometimes we feel at the hospital that we are quite poorly integrated. […] [For example] the palliation is started on our part together with the patient, who goes to the hospital for some reason and has theoretically done everything, the therapy was stopped and everything is clear. And then comes some senior physician who says: ‘we still have a chemo session for you which should be done’. No matter whether it is sensible or not. (G2)

To optimise IPC, most initiatives aim to disseminate a shared vision among HCPs in the wider community by showing the additional value of a proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach through education and participation:

… the health care professional needs to be aware of the existing possibilities [of palliative care] and that is what you try to disseminate in a hospital. That, well, that individual contact with patients, that they [other healthcare professionals] will really experience the additional value of it. And to the outside you try to present this [palliative care vision] by providing education … (NL5)

Patient flow

For most initiatives, ensuring that the right patients receive care at the right time from the right HCP depends on the knowledge of referring HCPs about palliative care and available palliative care services and whether HCPs are part of the extended network. Patient transfers are rarely based on standardised criteria, protocols or pathways. Participants report vulnerabilities during referrals and hospital discharges when HCPs in the wider community are involved.

Timely referrals to palliative care allow HCPs to develop relationships with patients and proactively identify and address problems and needs. However, according to participants, referrals often depend on HCPs who have insufficient knowledge of when to refer patients and are not always aware of available palliative care services. This particularly concerns patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure and other non-malignant chronic diseases with prolonged disease trajectories and less clear prognosis compared to patients with cancer and for whom palliative care services appear less developed and less HCPs seem part of the extended network:

I think that currently it is still the oncologic patients whose disease courses are most tangible and clear. We have been increasingly come into contact with heart failure patients, with kidney patients, with COPD patients. But it is a lot less obvious how these [disease] trajectories will go. For these patients palliative care is far less being applied. Actually, I think that Oncology has been the starting point for us as palliative team and I feel that you still see that this is the greatest group of patients for whom palliative care is being involved. (B1)

[…] and I think the professional relationships are different with cancer, COPD and chronic heart failure. We’re quite lucky: we know, (K), we know (T). (K) who works for COPD and (T) for heart failure […] so I think the professional relationships are different and that doesn’t have the same level of integration. (UK2)

Therefore, referrals still often occur too late:

We are often involved very late. And then they ask the team’s support […], but there is only little time left to be able to deal with all those [holistic] aspects. (B2–B3)

In order to encourage referrals, initiatives try to make referring HCPs part of their extended network, so that they become increasingly familiar with palliative care and the additional value of involving IPC initiatives:

[…] it has started with Oncology in the hospital and then the [other specialists] hear about it. You meet the entire hospital. So you’re starting to involve others as well. That’s how it happened with GPs as well. GPs who have good experiences with the palliative care network call more often. And they tell their colleagues: ‘Have you already thought about [involving] [case managers palliative care]?’ (NL3)

Hospital discharge also remains a challenge, especially for initiatives that are based in the community. Currently we often get a phone call like: ‘your patient is at home’, or the GP calls: ‘Oh it’s a disaster’, because someone has come home. We hurry to the home and find that nothing has been arranged. (B1) For these initiatives often only particular units in the hospital are part of their extended network:

[Community Matron]: […] the Discharge Co-ordinators which we have now started to build up a rapport and they know our patients and they’ll ring to say, ‘So-and-So is in hospital’, and […] as soon as they’re medically fit, we’ll go and see them. So they are improving but, as you say, it hasn’t been rolled out totally. It’s mostly on the medical respiratory wards that this is happening at the moment. (UK3)

Hospital-based initiatives report less difficulties with discharge, because HCPs from several hospital wards or in the community are part of their extended network and these initiatives have more possibilities to coordinate discharges themselves:

When the patient is still at the palliative station [palliative care unit] […] we have already taken part in the preparation for the patient’s discharge, the patient will have seen the negotiating partner and when the patient is at home, I pay a visit to check the home situation. At that point, community workers, […] try to support the patient and the relatives. (G2)

Information logistics

Ensuring that the right information is available at the right time for HCPs requires smooth information transfer between HCPs involved in the patient’s care. However, the quality of information transfer and the level of standardisation vary greatly among initiatives.

Participants report the highest quality of information transfer within the core team. These teams use a combination of communication channels and often standardise part of the information transfer specifically for core team members. For example, most initiatives have regular MDTs and some of them also use electronic systems to support information transfer. These systems are often only accessible to HCPs involved in the core team:

For the team, there are daily transmissions, weekly team meetings, which provide very good documentation in the computer system, I think, so that every point may be looked up regarding the current situation and the previous history. Especially important information is stored separately, as well, to make it more apparent. I think this is what is important. (G1)

Standardisation of when, how, which and with whom information is shared by means of protocols is not common. Nevertheless, because HCPs within extended networks and core teams know and trust each other, they have frequent contact, for example, by phone, face-to-face or personal notes, enabling information transfer:

[Communication] depends on […] the personal relationships of the doctors.(HU1)

What really advances [information transfer] is when we know each other personally. […] Not just on an institutional level. […] We have an idea of the other’s activities. It is easier to raise certain things, because we have a basic trust. And so, about what is inspiring and what causes obstacles. (G3)

However, according to HCPs within extended networks, barriers for information transfer also exist. For example, they are not automatically invited for regular core team MDTs or are not able to attend because their work schedules or locations do not permit them:

[Home help core team]: We don’t see [extended network member] often [at the MDTs]. We know that they are involved with the family, but they are not present at the meeting.

[Nurse extended network]: And are we invited?

[Home help core team]: Well, I don’t know. […]

[Social worker core team]: It depends on the question, but actually it would be better if you also attended, wouldn’t it? (BE2–3)

Limited standardisation of palliative care seems to be a predominant problem for the wider community, where HCPs are often not aware about the required information for providing IPC or lack any relationships with IPC professionals at all. Participants report that for this group information transfer is of limited quality, with the consequence that collecting the right information is often time consuming:

… a lot of the information we get is very poor, not very much at all. We spend a lot of our time digging for information, trying to ascertain exactly what’s happened, what they’ve [referring healthcare professionals] had done, what they haven’t had done, […] what the plan is. It can take us a couple of hours. (UK3)

Furthermore, limited standardisation means IPC professionals continuously need to adapt communication to the personal preferences and locally used communication channels of individual HCPs. Empathy and maintaining goodwill seem important, but adapting to individual wishes can also be demanding:

I find it very difficult that some of them [GPs] have very heterogeneous expectations about when, at what time, they want to be informed. […] There are no established basics in this area, and therefore, we always need a great deal of empathy and consideration because we can cause immense damage by failing to communicate. […] The system is actually quite tiresome, because it can only really be met when there is a full understanding of the usual personal information requirements. (G3)

Availability of (human) resources and material

Whether initiatives are successful in ensuring that the right professional and the right medication and equipment are available at the right time largely depends on the country. However, for all initiatives out-of-hours accessibility appears challenging.

Generally, several initiatives face problems with the funding and availability of trained staff. Attempts to solve the problem of out-of-hours accessibility are done by the initiatives in two ways. First, they aim at avoiding crisis situations during out-of-hours by planning care proactively:

Weekend and night-time periods are critical, so we must always think and act proactively about the weekend or the night in terms of either symptoms or drug therapy, and we should really make ourselves available, because if they fail to reach us, they will call the ambulance or the on-call duty service. (HU2)

Second, they make sure that someone is on call to give advice if a crisis situation does occur. Several initiatives have telephone consultation lines (e.g. locally provided by hospices, regional consultation lines or private phone numbers of IPC professionals) and some have connections with general practitioner (GP) on-call services that are available out-of-hours. These services are highly regarded by HCPs in the extended network:

As a GP, it gave an infinite sense of security that I could keep the patient at home. I have received support from the hospice care in this regard and the patient could feel safe, too. If you encountered any problems even at weekends or at night, the hospice doctor was able to help immediately. (HU1)

However, HCPs in the wider community often appear not to be aware of the available services and this could result in unnecessary hospital admissions:

[…] if the patient receives hospice care, several issues can be planned in advance. However, at night and weekends, the situation is still very critical at times. It is a problem that a lot of patients are sent from nursing homes to emergency treatment centres at weekends, while it could be solved locally. (H3)

Most initiatives report difficulties obtaining medication during out-of-hours sometimes when medication has not been arranged in advance and regular pharmacies are not open. Therefore, many initiatives have a ‘just-in-case’ stock of medicines or materials at the patient’s home or at the initiatives’ location to ensure availability if the clinical situation of the patient changes after hours:

Medication in the weekend is sometimes difficult when we are on-call. Well, you are called to start a sedation or something […] and then Dormicum is needed. Well, it was just recently that we needed to ask four pharmacies for medication. Well, that’s such a shame […] However, now we have a small stock [of medication] […]. And recently I was very happy that I had this stock. (B2–B3)

Furthermore, several initiatives have included a pharmacy in their extended network to solve problems with the availability of medication, particularly during out-of-hours:

We have a good working relationship with a pharmacy, which is available to us at all times. […] [Therefore] we are able to procure the patient’s medicine the same evening. (G1)

Table 4 displays a summary of the barriers and enablers for each integrated care domain identified in this study. The model initiatives use to realise IPC is based on building core teams of palliative care specialists and extended networks rather than developing standardised information exchange and referral pathways. Shared values and mutual trust within core teams and extended professional networks enable palliative care provision at the right time provided by the right HCP. Educational activities enable enhancing a shared proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach and extended networks. Informal contacts and electronic information systems allow for the right information to be available at the right time within core teams. Local solutions enable palliative care provision during out-of-hours. However, due to its informal nature and limited scope, integration of palliative care remains fragile and is jeopardised beyond extended networks. Furthermore, lack of (funding for) trained staff, medication and material hamper continuity of palliative care and oblige initiatives to use provisional solutions.

Table 4.

Summary of barriers and enablers for each domain of integrated palliative care identified in this study.

| Barrier | Enabler | |

|---|---|---|

| Content of care | Lack of palliative care knowledge/awareness among healthcare professionals in the wider professional community and therefore lack of a shared proactive multidisciplinary approach | Shared proactive multidisciplinary palliative care

approach Extended professional networks Education |

| Patient flow | Lack of awareness of available palliative care

services Lack of referral criteria, protocols and pathways |

Extended professional networks |

| Information logistics | Lack of widely shared electronic information systems or

information transfer protocols Multidisciplinary team meetings not always accessible beyond core teams |

Use of (electronic) information systems (although mainly

within core teams) Multidisciplinary team meetings, personal notes and phone calls Extended professional networks |

| Availability of (human) resources and material | Lack of (funding for) trained staff Lack of out-of-hour availability of staff, medication and material |

Local solutions, such as on-call (consultation) services

within small teams Just-in-case stocks for medicines and material Extended professional networks including pharmacies |

Discussion

This study examined how IPC takes shape across four domains: content of care, patient flow, information logistics and availability of (human) resources and material. We identified core teams, extended professional networks and the wider professional community to provide several limitations and enablers for better integration of palliative care. Enablers allow the initiatives to provide IPC on a small scale on informal basis within core teams and extended networks. However, initiatives report difficulties realising IPC in the wider community because these HCPs often do not share a proactive multidisciplinary palliative care approach, they do not know palliative care professionals personally and they do not have frequent contact.

Several studies16,28 confirm that inter-professional teamwork based on trust and shared knowledge, norms and values is an essential enabler for successful integrated care. Other studies19,20 underline that educational activities to make HCPs aware of and skilled in palliative care are an important element of IPC models. Moreover, expansion of basic palliative care training is seen as an important enabler for the integration of palliative care.21,29 However, the difficulties to integrate palliative care into the wider community due to barriers, such as a lack of palliative care knowledge and shared values, have been underlined in the literature as well.30,31 Since many HCPs have insufficient knowledge about what palliative care is, regard it as part of what they already do or consider it merely as terminal care and are focused on curing a disease,21,30,31 they do not recognise the additional value of collaborating with palliative care professionals.

Multidisciplinary teamwork and consultation are important components of horizontal integration.28,32 Comprehensive integration, however, also requires vertical integration, considered as adjacent levels in a chain of care.32 The initiatives in our study provide promising examples of vertical integration by starting from primary, secondary or tertiary care level and building relationships with HCPs working at other levels. However, many initiatives met difficulties particularly during transitions (referrals and discharge) suggesting that there is room for improvement, for example, using standardised care pathways.

The initiatives did not often make use of standardised care pathways, guidelines or electronic information systems beyond core teams. However, according to Fabbricotti,16 aligning tasks and procedures is one of the prerequisites for achieving enhanced integration. Although rigorous research on standardised information exchange in palliative care is lacking,33 literature shows that palliative care is only integrated in guidelines for cancer and chronic care to a limited extent,34,35 let alone its implementation into practice. Moreover, pathways and tools that guide HCPs to refer patients to palliative care in a timely way are being developed, but are not all validated yet.17–19

Although enhanced standardisation, such as the implementation of pathways and guidelines, is seen as an enabler for palliative care integration,29 this is probably not enough to fully realise integration. HCPs in the wider community first need to value the integration of palliative care in their clinical practice. Therefore, they need to explore and experience the surplus value of integrating palliative care. Examples are the recent integration of palliative care into oncology guidelines36 and the series about integration of palliative care into patients with COPD recently published in the Lancet.37 However, despite these promising examples, changing the attitudes among long-standing internal medical disciplines and GPs still remains a difficult task that will take time and effort.

Apart from building relationships and educational activities which were enablers in this study, enhanced evidence base is also seen as an enabler for palliative care integration.29 However, the optimal way to organise IPC in relation to patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes requires further research. Future research could, for example, focus on piloting implementation of a promising IPC model and conducting before and after implementation interviews with both HCPs and service users. Despite research and expert consultation, some prerequisites for achieving further integration are beyond the direct influence of palliative care professionals, including funding for trained palliative care staff, palliative care reimbursement, enhanced regulation and legislation.21,29 Therefore, support from external authorities, such as policy makers, insurance companies, research programmes and professional bodies, will probably be needed to fully achieve IPC.

Strengths and limitations

A large international group interview study with selected IPC initiatives in five European countries is a great and unique platform.18,30,38 It enabled collecting valuable in-depth data about how integrated care takes shape in practice within current IPC initiatives in Europe from the perspectives of HCPs. Due to the complex international context, it was difficult to fully achieve an iterative process39 of simultaneous data collection and analysis. Therefore, the data are possibly not as rich as intended. Although it would have been useful to describe examples of good practice of integration, this was not the focus of this article. However, detailed descriptions of some promising models in the InSup-C project have been described elsewhere.40

Conclusion

This study suggests that building core teams of palliative care specialists and professional networks based on personal relationships, shared norms and values and mutual trust is the dominant strategy for fostering IPC. However, convincing the wider community in order to achieve better integration into regular healthcare is a difficult task that will take time and effort. Moreover, enhancing standardisation of palliative care into education, referral pathways, protocols and guidelines as well as standardised information exchange may be needed as well. External authority will probably be needed to support IPC practices across settings. These insights should be prioritised by professional bodies, insurers and policy makers in order to promote IPC for patients with various disease backgrounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their valuable contributions to this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement no. 305555.

ORCID iD: Sheila Payne  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6982-9181

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6982-9181

References

- 1. Simmonds R, Glogowska M, McLachlan S, et al. Unplanned admissions and the organisational management of heart failure: a multicentre ethnographic, qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e007522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vermylen JH, Szmuilowicz E, Kalhan R. Palliative care in COPD: an unmet area for quality improvement. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015; 10: 1543–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beernaert K, Cohen J, Deliens L, et al. Referral to palliative care in COPD and other chronic diseases: a population-based study. Respir Med 2013; 107: 1731–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ko W, Deliens L, Miccinesi G, et al. Care provided and care setting transitions in the last three months of life of cancer patients: a nationwide monitoring study in four European countries. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Billingham MJ, Billingham SJ. Congruence between preferred and actual place of death according to the presence of malignant or non-malignant disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013; 3: 144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 9930: 1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 2745–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goodwin N. Understanding integrated care: a complex process, a fundamental principle. Int J Integr Care 2013; 13: e011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ewert B, Hodiamont F, van Wijngaarden J, et al. Building a taxonomy of integrated palliative care initiatives: results from a focus group. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016; 6: 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Firn J, Preston N, Walshe C. What are the views of hospital-based generalist palliative care professionals on what facilitates or hinders collaboration with in-patient specialist palliative care teams? A systematically constructed narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 240–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oishi A, Murtagh FE. The challenges of uncertainty and interprofessional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: a systematic review of views from patients, carers and health-care professionals. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 1081–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J 2010; 16: 423–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van der Klauw D, Molema H, Grooten L, et al. Identification of mechanisms enabling integrated care for patients with chronic diseases: a literature review. Int J Integr Care 2014; 14: e024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, et al. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care 2013; 13: e010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fabbricotti IN. Zorgen voor zorgketens: integratie en fragmentatie in de ontwikkeling van zorgketens. PhD Thesis, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, Rotterdam, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hui D, Mori M, Watanabe SM, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: e552–e559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gomez-Batiste X, Murray S, Thomas K, et al. Comprehensive and integrated palliative care for people with advanced chronic conditions: an update from several European initiatives and recommendations for policy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 16: 31203–31209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hui D, Bansal S, Strasser F, et al. Indicators of integration of oncology and palliative care programs: an international consensus. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1953–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siouta N, Van Beek K, Van der Eerden ME, et al. Integrated palliative care in Europe: a qualitative systematic literature review of empirically-tested models in cancer and chronic disease. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med 2015; 3: 224–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lynch T, Clark D, Centeno C, et al. Barriers to the development of palliative care in Western Europe. Palliat Med 2010; 24: 812–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frey JH, Fontana A. The group interview in social research. Soc Sci J 1991; 28: 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van der Eerden M, Csikos A, Busa C, et al. Experiences of patients, family and professional caregivers with integrated palliative care in Europe: protocol for an international, multicenter, prospective, mixed method study. BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Den Herder van der Eerden M, Hasselaar J, Payne S, et al. How continuity of care is experienced within the context of integrated palliative care: a qualitative study with patients and family caregivers in five European countries. Palliat Med 2017; 31: 946–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schrijvers G. Integrated care: better and cheaper. Amsterdam: Reed Business Information, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centeno C, Garralda E, Carrasco JM, et al. The palliative care challenge: analysis of barriers and opportunities to integrate palliative care in Europe in the view of national associations. J Palliat Med 2017; 20: 1195–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Albers G, Froggatt K, Van den Block L, et al. A qualitative exploration of the collaborative working between palliative care and geriatric medicine: barriers and facilitators from a European perspective. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kain DA, Eisenhauer EA. Early integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: evidence and overcoming barriers to implementation. Curr Oncol 2016; 23: 374–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas P, Meads G, Moustafa A, et al. Combined horizontal and vertical integration of care: a goal of practice-based commissioning. Qual Prim Care 2008; 16: 425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Petrova M, Riley J, Abel J, et al. Crash course in EPaCCS (Electronic Palliative Care Coordination Systems): 8 years of successes and failures in patient data sharing to learn from. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Epub ahead of print 16 September 2016. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Siouta N, Van Beek K, Preston N, et al. Towards integration of palliative care in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic literature review of European guidelines and pathways. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Beek K, Siouta N, Preston N, et al. To what degree is palliative care integrated in guidelines and pathways for adult cancer patients in Europe: a systematic literature review. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: ASCO clinical practice guideline update summary. J Oncol Pract 2017; 13: 119–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maddocks M, Lovell N, Booth S, et al. Palliative care and management of troublesome symptoms for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2017; 390: 988–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Van Riet Paap J, Vernooij-Dassen M, Brouwer F, et al. Improving the organization of palliative care: identification of barriers and facilitators in five European countries. Implement Sci 2014; 9: 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Z Soziol 1990; 19: 418–427. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hasselaar J, Payne S. Integrated palliative care. Nijmegen: Radboud University Medical Center, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.