Abstract

Background:

The necessity of a second venous anastomosis in free flap surgery is controversial. The purpose of this systematic review is to determine whether venous flap failure and reoperation rates are lower when 2 venous anastomoses are performed. The secondary objective is to determine whether venous flap failure and reoperation rates are lower when the 2 veins are from 2 different drainage systems.

Methods:

A comprehensive search of the literature identified relevant studies. Investigators independently extracted data on rates of flap failure and reoperation secondary to venous congestion. A meta-analysis was performed; odds ratios (ORs) were pooled using a random-effects model and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

Of 18 190 studies identified, 15 were included for analysis. The mean sample size was 287 patients (minimum = 102, maximum = 564). No statistically significant difference in venous flap failure was found when comparing 1 versus 2 venous anastomoses (OR: 1.35; 95% CI: 0.46-3.93). A significant decrease in reoperation rate due to venous congestion was shown (OR: 3.03; 95% CI: 1.64-5.58). The results favor using 2 veins from 2 different systems over veins from the same system (OR: 0.16; 95% CI: 0.02-1.27).

Conclusions:

There is low-quality evidence suggesting that the use of 2 venous anastomoses will lower the rate of reoperation due to venous congestion. There are insufficient data published to meaningfully compare outcomes of flaps with 2 venous anastomoses from different systems to flaps with anastomoses from the same system.

Keywords: microsurgery, flap failure, venous anastomoses

Abstract

Historique :

La nécessité d’une deuxième anastomose veineuse lors d’une opération par lambeau libre est matière à controverse. La présente analyse systématique visait à déterminer si l’échec du lambeau veineux et le taux de réopération étaient plus faibles après deux anastomoses veineuses. L’objectif secondaire consistait à déterminer si l’échec du lambeau veineux et le taux de réopération étaient plus faibles lorsque les deux veines provenaient de deux systèmes de drainage différents.

Méthodologie :

Les chercheurs ont repéré les études pertinentes au moyen d’une recherche approfondie des publications. De manière indépendante, ils ont extrait les données sur le taux d’échec des lambeaux et des réopérations après une congestion veineuse. Ils ont procédé à une méta-analyse et ont regroupé les rapports de cote (RC) au moyen d’un modèle à effet aléatoire et d’intervalles de confiance (IC) à 95 %.

Résultats :

Sur les 18 190 études extraites, les chercheurs en ont inclus 15 dans l’analyse. Leur échantillon moyen était de 287 patients (minimum 102, maximum 564). Ils n’ont pas constaté de différence statistiquement significative des échecs des lambeaux lorsqu’ils comparaient une ou deux anastomoses veineuses (RC 1,35; IC à 95 % 0,46 à 3,93). Ils ont constaté une diminution significative du taux de réopérations attribuables à une congestion veineuse (RC 3,03; IC à 95 % 1,64 à 5,58). Les résultats favorisent le recours à deux veines de deux systèmes veineux différents plutôt que d’un même système (RC 0,16; IC à 95 % 0,02 à 1,27).

Conclusions :

Selon des preuves de faible qualité, le recours à deux anastomoses veineuses réduit le taux de réopérations attribuables à une congestion veineuse. Les données publiées sont insuffisantes pour comparer de manière significative les résultats des lambeaux de deux anastomoses provenant de systèmes différents à ceux des lambeaux provenant d’un même système.

Introduction

Free flap failure occurs in 2% to 7% of cases.1 This is a devastating complication for the patient, surgeon, and health-care team. A return to the operating room for venous insufficiency occurs in approximately 7% of cases.2 These “take-backs” increase the cost of a patient’s reconstruction. As a result, determining the factors associated with flap failure continues to be prevalent in the literature.3

Venous thrombosis and/or insufficiency has been reported as a more common reason for flap compromise compared to arterial problem.2,4 Proponents of dual venous anastomoses suggest that a second vein provides “back up” outflow in the case of venous thrombosis.5,6 Similarly, a second venous anastomosis could ensure adequate outflow in flaps that are not sufficiently drained by a single vein.6-8 The time and cost associated with an additional anastomosis must also be considered.9,10

The evidence to date is not conclusive. Some report improved flap survival when 2 veins are anastomosed,5,11 while others report no difference.9,12 Findings of improved survival in flaps drained by 1 vein can also be found.13 Studies with fewer take-backs for venous congestion without a difference in flap survival for 2-vein flaps have also been published.6,14 An additional variable to consider is whether the flap veins originate from the same system or different systems (ie, a deep and a superficial vein). Ichinose et al and Enajat et al have each reported excellent outcomes when anastomosing 2 veins from 2 different systems.6,15

A systematic review by Ahmadi et al compared the rate of venous thrombosis and flap failure when performing 1 or 2 venous anastamoses. They concluded that performing 2 venous anastamoses reduced the incidence of flap failure by 36% and venous thrombosis by 34%.16 There are a number of methodological elements in the study by Ahmadi et al that we sought to address in our systemic review and meta-analysis. (1) The clinically relevant outcome of the rate of reoperation due to venous congestion was not evaluated. (2) Since the literature search by Ahmadi et al was completed, 2 retrospective case series, evaluating large numbers of patients, have been published.8,9 (3) The influence of using veins from different systems was not evaluated. (4) The inclusion criteria in the study by Ahmadi et al encompassed studies with very small flap numbers,17,18 including some that recorded zero free flap failures.19 These small studies may skew the results of meta-analysis.

The purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine whether the rate of venous flap failure and the rate of venous congestion requiring reoperation are lower when 2 venous anastomoses are performed compared to 1 anastomosis. The secondary objective is to determine, in flaps with 2 venous anastomoses, whether the rates of venous flap failure and venous congestion requiring reoperation are lower when 1 vein comes from a superficial system and 1 from a deep system compared to when both veins are from the same system.

Methods

Study Eligibility

Inclusion criteria consisted of studies (1) pertaining to human participants; (2) including patients who underwent free flap surgery; (3) comparing outcomes of 1 versus 2 venous anastomoses; and (4) with design of a systematic review, randomized controlled trial (RCT), cohort, case–control, or case series. Exclusion criteria consisted of (1) studies in a language other than English; (2) case reports; (3) studies, abstracts, or conference proceedings with insufficient data; and (4) a sample size of less than 30 patients in a single study group.

Search Strategy

An electronic search of The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, and Embase databases was conducted in consultation with a McMaster University medical librarian, last updated September 2014. Keywords and subject headings “surgical flap” and “free tissue flap” were used. The search was limited to articles published in English since 1980. Study references were screened manually to identify potential citations to augment the initial database search. National and international trial registers including centerwatch.com, controlled-trials.com, and clinicaltrials.gov were searched for any ongoing or recently completed RCTs.

Study Selection

Two reviewers (J.L.K.M. and D.G.) independently screened titles and abstracts for predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Both reviewers then independently performed full-text review of potential studies for final inclusion. Disagreements among reviewers were resolved by consulting an arbitrator (S.H.V.).

Data Extraction and Methodological Quality

Data to be extracted were decided a priori and consisted of number of patients, age, gender, comorbidities (smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus), type of free flap performed, recipient site, total reoperation rate, reoperation rate secondary to venous congestion, free flap venous failure rate, total operative time, and the reason for choosing 1 or 2 venous anastomoses.

Two independent reviewers (J.L.K.M. and N.A.) extracted and entered the data into a predefined standardized form. In the case of any disagreements, resolution was achieved with the help of an arbitrator (S.H.V.). Authors were contacted by e-mail when relevant data were missing.

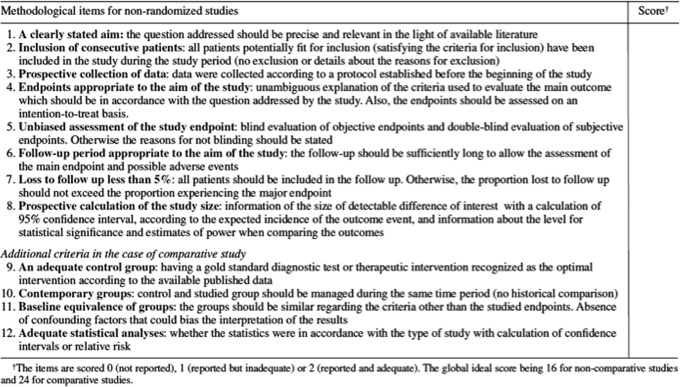

The methodological quality of each study was assessed by 2 independent reviewers (J.L.K.M. and N.A.) using the Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS) scale (Appendix A).20

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were pooled from all included studies using a random-effects model with inverse variance approach. The first analysis conducted pooled all studies that compared 1 versus 2 venous anastomoses. Subgroup analysis was performed for studies with the primary objective of comparing 1 versus 2 venous anastomoses. Cochrane’s Q and the I 2 statistic were used to assess the presence and extent of heterogeneity among studies.21

Clinical heterogeneity was incorporated into the random-effects model. Sources of clinical heterogeneity were identified a priori: flap type, recipient site, patient comorbidities, surgical technique, and surgeon experience. Review Manger 5.3 (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman/) was used for data analysis.

Results

Literature Search

The literature search yielded 18 190 potentially eligible studies, of which 15 were selected for inclusion and analysis (Figure 1). All included studies were retrospective case series.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Study Characteristics

Studies were published from 2003 to 2014 and included free flap surgeries performed between 1987 and 2011. Calculated mean sample size was 287 patients (102-564). Mean patient age was 51.4 (2-89) years.

Seven of the 15 studies had a primary objective of comparing 1 versus 2 venous anastomoses.5-9,14,22 Six studies utilized various types of free flaps,5,13,22-25 5 used the radial forearm free flap (RFFF) only,7,11,26-28 2 utilized the deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap or transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap only,6,14 1 used anterolateral thigh only,8 and 1 performed osteocutaneous fibula only.9

The recipient sites for the free flaps also differed between studies. The head and neck, breast, and lower extremity were the sole recipient sites in 9, 2, and 1 studies, respectively. Only 3 studies reported operative time; therefore, no analysis of this variable was performed.

Methodological Quality

The majority of studies were of low methodological quality, with a mean MINORS score of 11.9/24 (8-15) and 7.2/18 (6-8) for comparative and non-comparative studies, respectively.

Flap Failure and Reoperation Rates

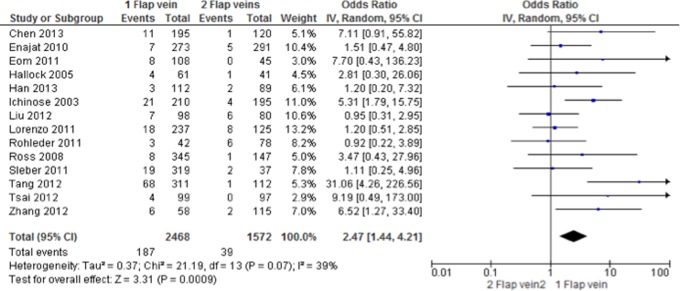

Twelve studies reported venous flap failure rates (Figure 2). No statistically significant difference was found between 1 and 2 venous anastomoses, with a calculated OR of 1.35 (95% CI: 0.46-3.93). Substantial heterogeneity was present among these studies (I 2 = 52%).29 Fourteen studies reported the rate of reoperation due to venous congestion (Figure 3). Heterogeneity was moderate with an I 2 of 39%. When 2 veins were used, a significant decrease in the rate of reoperation secondary to venous congestion was shown (OR: 2.47; 95% CI: 1.44-4.21).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of free flap venous failures—all studies.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of reoperations secondary to venous congestion—all studies.

Subgroup analysis of the 7 studies that had a primary objective of comparing 1 to 2 venous anastomoses is presented in Figures 4 and 5. There was a decrease in heterogeneity among these studies. No difference in free flap venous failure rate was again found (OR: 1.35; 95% CI: 0.46-3.93). A significant decrease in the rate of reoperation due to venous congestion was illustrated when 2 vein were used (OR: 3.03; 95% CI: 1.64-5.58).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of free flap venous failures—subgroup analysis of studies explicitly comparing the effect of 1 versus 2 venous anastamoses.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of reoperations secondary to venous congestion—subgroup analysis of studies explicitly comparing the effect of 1 versus 2 venous anastamoses.

Just 3 studies compared free flaps with 2 venous anastomoses from different systems to those with 2 anastomoses from the same system (Figure 6). The results favor using 2 veins from 2 different systems (OR: 0.16; 95% CI: 0.02-1.27), though substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 72%) was present.

Figure 6.

Forest plot—reoperations secondary to venous congestion: 2 venous anastomoses from different systems (2V2 S) versus 2 anastomoses from same system (2V1 S).

Discussion

It may seem intuitive to perform multiple venous anastomoses to reduce the risk of venous insufficiency or provide “backup” outflow in the setting of thrombosis; however, the evidence to date is inconclusive.5,8,9 This meta-analysis did not demonstrate venous flap failure rate to be influenced by the number of venous anastomoses (Figures 2 and 4). The literature contains individual studies that show fewer failures with 1 vein,13,27 while others show decreased failure rates with 2 veins.11,28 Therefore, a reasonable conclusion might be that flap failure is a multifactorial complication.

Vascular complications leading to flap failure can include venous thrombosis, arterial thrombosis, or both. Reasons for flap failure can be divided into technical factors and patient factors. Technical factors, including flap design and surgeon error, are considered common causes of vessel thrombosis.30 Surgical team errors are difficult to quantify; however, an attempt should be made to document technical challenges.31 The studies included in this analysis did not consider these issues with 2 exceptions.5,11 Patient factors, including the known (eg, age, smoking, obesity, and radiation) and unknown (eg, unknown coagulopathy and unknown medication effects), can also contribute to vascular compromise.23,30,31 There is no justification for not including a complete list of patient factors and operative details.

Ultimately, for each free flap case, there may be a single distinct event or a summation of minute technical and patient-related variables that could lead to flap failure. In some cases, the number of venous anastomoses might contribute to flap failure. Where 2 venous anastomoses are possible, the surgical team must make a decision if a second vein will be anastomosed. At this time, the evidence does not support performing a second anastomosis in all patients to reduce the risk of flap failure. Increased operative time and costs are also not strongly supported as reasons to limit the number of anastomoses.6,8 This is particularly true with the increased use of coupling devices.6 Thus, this decision will be influenced by surgeon experience, surgeon preference, patient factors, and intraoperative details rather than the existence of convincing evidence.

The second outcome evaluated is the rate of venous congestion. A significant benefit was found for flaps with 2 venous anastomoses (Figures 3 and 5), with a number needed to treat of 20. Therefore, for every 20 flaps, if 2 veins are anastomosed, it will save 1 of these 20 patients an additional operation due to venous congestion. The cost of an extra anastomosis should be weighed against the cost of an emergent return to the operating room. Of note, while the evidence supports preforming 2 venous anastomoses to reduce the incidence of venous congestion, there is no apparent benefit to flap failure rate (Figures 2 and 4).

Venous insufficiency can result from poor flap design, variations in venous drainage patterns, or with the formation of a thrombus. Due to the lack of details provided by the available studies, it is difficult to know why 2 veins reduces the incidence of venous congestion. In the cases where 1 vein is inadequate or thrombosed, the idea of “backup” outflow is supported by Enajat et al6 In their study, 1 or 2 venous anastomoses were performed in DIEP flaps for breast reconstruction. Each anastomoses had an implantable Doppler placed for monitoring. Ten flaps were brought back to the operating room for exploration after loss of a Doppler signal, 5 with 1 venous anastomosis and 5 with 2. Even though all 10 flaps had a thrombosed vein, only the flaps from the 1-vein group all showed clinical signs of venous congestion and required revision, whereas the 2-vein group did not. The authors suggest this is on account of the second vein providing adequate drainage for the flap. Based on clinical evaluation, the 5 flaps in the 2-vein group would not typically undergo re-exploration, thus saving health-care resources.

Conversely, other data support the use of 1 vein. A physiologic study of blood velocity by Hanasono et al demonstrated that in flaps where 2 venae comitantes (VCs) are anastomosed, the venous blood flow is slowed to less than half the velocity of a single vein flap.10 Since low flow states are a risk factor for thrombosis, a single VC anastomosis was favored over 2, even though there were no flap failures or take-backs in their study.10

The studies by Enajat et al and Hanasono et al appear to be contradictory. Yet, another variable to consider is whether the veins come from the superficial or deep system. The third outcome of this study was to look at flaps with 2 venous anastomoses and investigate whether there was a difference when the veins came from the same or different venous drainage systems. Unfortunately, only 3 studies met the inclusion criteria. These studies had a substantial amount of heterogeneity and did not provide sufficient data to answer the clinical question. Nevertheless, the results did favor using 2 veins from different systems. Enajat et al and Ichinose et al looked at the 2 most common flaps where there is an opportunity to perform 2 anastomoses from 2 different systems, the DIEP flap and RFFF. As previously discussed, Enajat et al provides compelling evidence that a second venous anastomosis from a separate system reduced the incidence of venous congestion, even in the setting of thrombosis.6 Ichinose et al also demonstrated the take-back rate for venous thrombosis to be significantly lower when 2 venous systems are used in the RFFF.32 Their study also looked at a subset of flaps in which 2 veins from 2 systems in the flap were anastomosed to 2 veins from 2 systems in the recipient site (internal and external jugular). This group of 135 flaps was the only group to have zero take-backs for venous thrombosis.32

A potential advantage of connecting 2 veins from 2 systems is that flow in deep and superficial veins should be independent of each other. This is in contrast to the 2 deep system veins (VCs) that have multiple connections. If a thrombus forms in 1 VC, it is reasonable to expect flow in the other VC to be negatively impacted. Hanasono et al provides evidence that deep system veins are connected and that anastomosing 1 veins from the deep system (VCs) could be detrimental.10

Several challenges were met when conducting this systematic review. First, a large number of studies were identified in the original search (Figure 1). Non-specific search terms were required due to the way microsurgery papers are currently indexed in electronic databases. Second, only about half (7 of 15) of the studies had a primary objective of directly comparing flaps with 1 venous anastomosis versus those with 2. In the remaining studies, it was a secondary or tertiary objective. Third, the overall quality of studies was poor, and this is reflected in the low MINOR scores. There were no randomized control trials despite the fact that this research question is suitable to randomization. All studies were retrospective, and the majority (10 of 15) were non-comparative without any evaluation of patient factors. The lack of patient details considerably limited the statistical tests that could be applied in our meta-analysis. Finally, the studies analyzed were heterogeneous. Reporting of the flap type, recipient site, number, and experience of surgeons involved was variable.

Several studies were excluded from this meta-analysis due to small sample size either overall or in a single study group (ie, either 1 vein or 2 vein groups).10,17-19 These studies were excluded because their results were deemed less reliable, evident by a zero flap failure rate in several.13,17,10 The use of these studies in other meta-analyses likely contributed to the finding that 2 venous anastomoses improved free flap failure rates.16,33

Conclusions

Flap failure is undoubtedly multifactorial; however, the current literature has been unable to elucidate whether the number of venous anastomoses is one such factor. This systematic review determined that there is a lack of strong evidence when comparing flaps with 1 versus 2 venous anastomoses. The meta-analysis further demonstrated that free flap failure is equivocal in 1-vein and 2-vein flaps. The one subgroup where there may be value is when the 2 veins of the flap originate from different systems (deep and superficial). Although there are insufficient data at this time, the results are promising and the physiologic argument makes sense.

This meta-analysis shows a reduction in free flap take-backs for venous congestion in 2-vein flaps, despite no difference in flap failure. Furthermore, there may be an additional benefit if the 2 veins are from 2 different systems. Fewer take-backs could have an impact both economically on the health-care system and psychologically on the patient and health-care team, despite the extra work involved in a second anastomosis.

Appendix A

The revised and validated verison of MINORS.20

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: Therapeutic Level 3

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Disa JJ, Cordeiro PG, Hidalgo DA. Efficacy of conventional monitoring techniques in free tissue transfer: an 11-year experience in 750 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(1):97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coroneos CJ, Heller AM, Voineskos SH, Avram R. SIEA versus DIEP arterial complications: a cohort study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(5):802e–807e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wong AK, Joanna Nguyen T, Peric M, et al. Analysis of risk factors associated with microvascular free flap failure using a multi-institutional database. Microsurgery. 2015;35(1):6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hidalgo DA, Disa JJ, Cordeiro PG, Hu QY. A review of 716 consecutive free flaps for oncologic surgical defects: refinement in donor-site selection and technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(3):722–732; discussion 733-734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ross GL, Ang ES, Lannon D, et al. Ten-year experience of free flaps in head and neck surgery. How necessary is a second venous anastomosis? Head Neck. 2008;30(8):1086–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Enajat M, Rozen WM, Whitaker IS, Smit JM, Acosta R. A single center comparison of one versus two venous anastomoses in 564 consecutive DIEP flaps: investigating the effect on venous congestion and flap survival. Microsurgery. 2010;30(3):185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ichinose A, Terashi H, Nakahara M, et al. Do multiple venous anastomoses reduce risk of thrombosis in free-flap transfer? Efficacy of dual anastomoses of separate venous systems. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(1):61–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen WF, Kung YP, Kang YC, Lawrence WT, Tsao CK. An old controversy revisited-one versus two venous anastomoses in microvascular head and neck reconstruction using anterolateral thigh flap. Microsurgery. 2014;34(5):377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Han Z, Li J, Li H, Su M, Qin L. Single versus dual venous anastomoses of the free fibula osteocutaneous flap in mandibular reconstruction: a retrospective study. Microsurgery. 2013;33(8):652–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanasono MM, Kocak E, Ogunleye O, Hartley CJ, Miller MJ. One versus two venous anastomoses in microvascular free flap surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(5):1548–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rohleder NH, Wolff KD, Holzle F, et al. Secondary maxillofacial reconstruction with the radial forearm free flap: a standard operating procedure for the venous microanastomoses. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(7):1980–1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hallock GG, Rice DC. Efficacy of venous supercharging of the deep inferior epigastric perforator flap in a rat model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(2):551–555; discussion 556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lorenzo AR, Lin CH, Lin CH, et al. Selection of the recipient vein in microvascular flap reconstruction of the lower extremity: analysis of 362 free-tissue transfers. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(5):649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eom JS, Sun SH, Lee TJ. Selection of the recipient veins for additional anastomosis of the superficial inferior epigastric vein in breast reconstruction with free transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous or deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;67(5):505–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ichinose A, Tahara S, Terashi H, Yokoo S. Reestablished circulation after free radial forearm flap transfer. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2004;20(3):207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahmadi I, Herle P, Rozen WM, Leong J. One versus two venous anastomoses in microsurgical free flaps: a meta-analysis. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2014;30(6):413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jandali S, Wu LC, Vega SJ, Kovach SJ, Serletti JM. 1000 consecutive venous anastomoses using the microvascular anastomotic coupler in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):792–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamashiro M, Hasegawa K, Uzawa N, et al. Complications and outcome of free flap transfers for oral and maxillofacial reconstruction: analysis of 213 cases. Oral Sci Inter. 2009;6(1):46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun G, Lu M, Hu Q, Tang E, Yang X, Wang Z. Clinical application of thin anterolateral thigh flap in the reconstruction of intraoral defects. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115(2):185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(9):712–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hallock GG. Both superficial and deep extremity veins can be used successfully as the recipient site for free flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44(6):633–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joo YH, Sun DI, Park JO, Cho KJ, Kim MS. Risk factors of free flap compromise in 247 cases of microvascular head and neck reconstruction: a single surgeon’s experience. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267(10):1629–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsai YT, Lin TS. The suitability of end-to-side microvascular anastomosis in free flap transfer for limb reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68(2):171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang T, Lubek J, Salama A, et al. Venous anastomoses using microvascular coupler in free flap head and neck reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(4):992–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu Y, Zhao YF, Huang JT, et al. Analysis of 13 cases of venous compromise in 178 radial forearm free flaps for intraoral reconstruction. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41(4):448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Selber JC, Sanders E, Lin H, Yu P. Venous drainage of the radial forearm flap: comparison of the deep and superficial systems. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66(4):347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tang Z, Zhou Z, Wang D, et al. Free radial forearm flaps: an overview of our clinical experience and exploration of relevant issues. Int Symp Inf Technol Med Educ. 2012;1:524–528. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins JP, Green SE. Cochrane Handbook For Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. Chichester, England; John Wiley & Sons: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nahabedian MY, Momen B, Manson PN. Factors associated with anastomotic failure after microvascular reconstruction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(1):74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mirzabeigi MN, Wang T, Kovach SJ, Taylor JA, Serletti JM, Wu LC. Free flap take-back following postoperative microvascular compromise: predicting salvage versus failure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(3):579–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ichinose A, Tahara S, Yokoo S, et al. Fail-safe drainage procedure in free radial forearm flap transfer. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2003;19(6):371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Riot S, Herlin C, Mojallal A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of double venous anastomosis in free flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(6):1299–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]