Abstract

Background and objectives

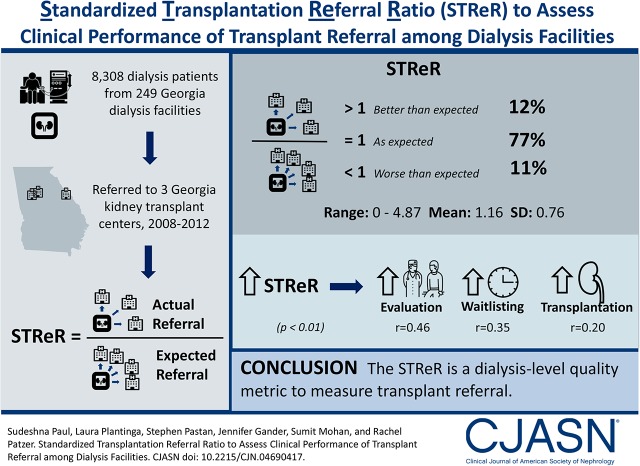

For patients with ESRD, referral from a dialysis facility to a transplant center for evaluation is an important step toward kidney transplantation. However, a standardized measure for assessing clinical performance of dialysis facilities transplant access is lacking. We describe methodology for a new dialysis facility measure: the Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratio.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Transplant referral data from 8308 patients with incident ESRD within 249 dialysis facilities in the United States state of Georgia were linked with US Renal Data System data from January of 2008 to December of 2011, with follow-up through December of 2012. Facility-level expected referrals were computed from a two-stage Cox proportional hazards model after patient case mix risk adjustment including demographics and comorbidities. The Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratio (95% confidence interval) was calculated as a ratio of observed to expected referrals. Measure validity and reliability were assessed.

Results

Over 2008–2011, facility Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratios in Georgia ranged from 0 to 4.87 (mean =1.16, SD=0.76). Most (77%) facilities had observed referrals as expected, whereas 11% and 12% had Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratios significantly greater than and less than expected, respectively. Age, race, sex, and comorbid conditions were significantly associated with the likelihood of referral, and they were included in risk adjustment for Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratio calculations. The Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratios were positively associated with evaluation, waitlisting, and transplantation (r=0.46, 0.35, and 0.20, respectively; P<0.01). On average, approximately 33% of the variability in Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratios was attributed to between-facility variation, and 67% of the variability in Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratios was attributed to within-facility variation.

Conclusions

The majority of observed variation in dialysis facility referral performance was due to characteristics within a dialysis facility rather than patient factors included in risk adjustment models. Our study shows a method for computing a facility-level standardized measure for transplant referral on the basis of a pilot sample of Georgia dialysis facilities that could be used to monitor transplant referral performance of dialysis facilities.

Keywords: kidney transplantation; evaluation referral; quality measure; end stage renal disease; Proportional Hazards Models; Risk Adjustment; Comorbidity; Confidence Intervals; Follow-Up Studies; Reproducibility of Results; Kidney Failure, Chronic; kidney, Probability; Referral and Consultation; Demography; Diagnosis-Related Groups; renal dialysis

Introduction

Although kidney transplantation is the optimal treatment for most of nearly 700,000 patients with ESRD in the United States, approximately 13% are waitlisted for transplantation, and of those, <20% get transplanted each year (1). Prior research has attributed poor access to kidney transplantation to gaps along the continuum of care for patients with ESRD (2,3). Although the effects of dialysis facility– and patient-level factors on waitlisting and transplantation have been studied (2–9), their effects on earlier steps, such as receiving education about the benefits of transplantation and referral from dialysis facilities to a transplant center for evaluation, have been understudied. With statewide data collection on transplant referral through the Southeastern Kidney Transplant Coalition, we previously reported wide variation in facility referral for kidney transplantation in the state of Georgia, where some facilities referred no patients and others referred up to 76% of their patient population (3). This wide variation suggests a need to examine referral as a quality metric for dialysis facilities, because no dialysis facility–based quality metrics for transplant access currently exist.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) plays a primary role in the development of new quality measures for dialysis facilities pertaining to their care of patients with ESRD. In 2015, the ESRD Access to Kidney Transplantation Technical Expert Panel identified several important quality gaps and considered development of several dialysis facility–level measures at the early steps, including transplant referral and waitlisting, for overall improved access (10). In addition, the kidney community has called for national collection of transplant referral data for use as a clinical measure to improve performance and equity in access to kidney transplantation (11,12).

Referral to a transplant center is an essential first step for patients to be considered candidates for kidney transplantation. Although national transplant referral data are unavailable, we recently collected patient referral data from all Georgia transplant centers as part of the Reducing Disparities in Access to Kidney Transplantation Community Study, and an extension of this data collection in other states is underway (13). The few studies that have examined transplant performance using transplant referral have used facility-level absolute referral rate to measure facility performance (3,14,15). In a recent study, we examined whether absolute facility referral was associated with other quality metrics within dialysis facilities and found that referral was not associated with other metrics, such as anemia management, morbidity, or mortality, and although referral was associated with waitlisting and transplantation, it was not entirely correspondent with these other measures of transplant access. These results suggest a need for a quality metric for transplant referral rather than waitlisting and transplantation, which may be more driven by organ supply or transplant center practices than dialysis facility attributes, whereas referral is more directly tied to the dialysis facility. Finally, because variation in referrals can be attributable to patient case mix within facilities, a risk-adjusted transplant referral measure is essential to effectively assess dialysis facility performance. The purpose of this study was to present a risk-adjusted quality metric, the Standardized Transplantation Referral Ratio (STReR), to evaluate dialysis facility performance in transplantation referrals relative to a regional average with similar patient case mix. We expect that this metric could be adapted in a larger, national population if national data on transplant referral are collected in the future.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

Patient-level data on transplant referrals between 2008 and 2012 were collected from all three transplant centers in the state of Georgia (Emory Transplant Center [Atlanta], Augusta University Medical Center [Augusta], and Piedmont Transplant Institute [Atlanta]) as previously described (3,16). ESRD Network 6 served as the data coordinating center and linked patient-level referral data with dialysis facility data by unique provider number.

To ensure complete patient follow-up and identify a cohort of nonreferred patients with ESRD in Georgia during the same time period, referral data were linked to the 2015 US Renal Data System (USRDS) standard analytic files, resulting in complete follow-up on patients with ESRD through December 31, 2012. The USRDS is a national surveillance data system that aggregates demographic, diagnosis, treatment, and facility information on nearly 2.5 million patients with ESRD from various data sources, including the Medical Evidence Report (CMS-2728), which is completed for all patients with ESRD at the start of ESRD, as well as United Network for Organ Sharing files on waitlisting and transplantation events.

Patients above 70 years old and those without an ESRD start date were excluded. Facilities with extremely low volumes can unduly influence the estimation of expected risk of referrals. Because the STReR provides little information about the underlying relative rates of these facilities, we limited our analysis to facilities with at least five incident patients per year. In sensitivity analyses, we calculated STReR for the 72 Georgia facilities excluded due to annual incidence of less than five.

Our final cohort included 8308 patients with incident ESRD receiving services at 249 Georgia facilities between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011 who were followed through December 31, 2012.

Study Variables

Analogous to existing CMS standardized quality measures (e.g., Standardized Mortality Ratio and Standardized Hospitalization Ratio), the STReR measure compares the observed number of referrals among patients with incident ESRD within a facility (numerator) with an expected number of patients with ESRD in Georgia adjusted for the patient characteristics (case mix) in that facility (denominator).

Outcome Definition

The outcome for this measure is the risk-adjusted dialysis facility–level count of adult Georgia patients on dialysis referred for transplant evaluation to one of the three Georgia transplant centers.

Referral for kidney transplantation was defined as the date on which the transplant center received a transplant referral form from a dialysis facility or referring provider. Only a patient’s first referral was counted in the event of multiple referrals.

The sample of patients with incident ESRD between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011 was followed for 1 year (last date of follow-up was December 31, 2012) or until their first referral, transplant, or death, whichever occurred first. Patients were assigned to a facility immediately after they started dialysis therapy at that facility. Facility transitions within the first year were accounted for to accurately calculate at-risk time of patients at each facility. For example, for a patient who received services at facility A for 8 months and then facility B for 4 months, the patient was considered to have an at-risk period of 0.67 years in facility A and 0.33 years in facility B.

Risk Adjustment Using Cox Proportional Hazards Model

To compute expected referrals at the facility level, we adjusted for risk factors of age, race, sex, body mass index (BMI), calendar year of incidence, and other comorbidities at ESRD start (e.g., congestive heart failure, atherosclerotic heart disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, diabetes, tobacco use, cancer, and nursing home status) in alignment with the CMS’s existing dialysis facility measures of hospitalization and mortality.

A two-stage Cox proportional hazards model was used to compute the expected number of first year referrals at a facility (details are in Supplemental Material). The facility STReRs were obtained as a ratio of observed to expected referrals. Model fit was tested by comparing the risk-adjusted model with an unadjusted model using the Akaike information criterion (AIC).

STReR and 95% Confidence Intervals

By definition, an STReR value close to one indicates perfect agreement between observed referrals and those expected on the basis of facility case mix, whereas an STReR of less than one indicates that the facility’s transplant referral rate is lower than expected. Because of low first year observed referrals (approximately 75% of facilities had <15 referrals), exact 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for observed referrals and divided by the expected referrals to obtain the exact 95% CI of STReR (17). Patients with missing data were not excluded from the STReR calculation. Around 3% of the patients (n=257) had missing BMI, and <1% (n=32) had missing comorbidities. No patients were missing age, race, sex, or date of first ESRD treatment. For the purposes of calculation, missing values of BMI were replaced with mean values for patients of similar age and identical race and sex. Indicator variables identifying patients with missing values for comorbidities were included as covariates in the model.

Reliability

The reliability of STReR was assessed using interunit reliability (IUR) (18). A higher IUR (close to one) indicated that the variation between the STReRs was due to real facility-level differences and was not driven by random noise.

Validity

To assess predictive validity of the metric, we examined how well the STReR predicted downstream kidney transplant outcomes. Of those referred, facility proportions of evaluation, waitlisting, and transplantation within 6, 12, and 24 months of referral, respectively, were computed. Associations with STReRs were examined using Spearman rank correlations.

Data management and statistical analyses were performed in STATA 14.2 and SAS 9.3. SAS code for the calculation of STReR is included in Supplemental Material.

Results

Study Population

The study population included 9067 adult patients with incident ESRD receiving services at 321 Georgia dialysis facilities between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011, with follow-up through December 31, 2012. Of those facilities, 72 had fewer than five incident patients per year between 2008 and 2011 and were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 8308 incident patients in 249 facilities included in the final study population (Table 1), a total of 2542 (31%) had first referrals within 1 year of dialysis start. The median time to referral from assignment to the first dialysis facility was 115 days (interquartile range, 60–200 days). There were two first transplants and 940 deaths among patients within the first year of ESRD incidence over the study course. Population characteristics of Georgia patients on incident dialysis between 2008 and 2011 are summarized in Table 1. The crude number of first year referrals varied between 557 in 2008 and 708 in 2011 (i.e., crude referral proportions of 0.27–0.34 over the 4 years). The 4-year crude referral proportion for Georgia dialysis facilities was 0.31.

Table 1.

Referrals to kidney transplantation among Georgia patients on incident dialysis for data years 2008–2011

| Incident Year | Dialysis Facilities | Patients on Dialysis | Transplant Referrals within 1 yr of ESRD Start | Crude Transplant Referral Proportiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 177 | 2058 | 557 | 0.27 |

| 2009 | 194 | 2147 | 626 | 0.29 |

| 2010 | 189 | 2040 | 651 | 0.32 |

| 2011 | 200 | 2063 | 708 | 0.34 |

| Total | 249 | 8308 | 2542 | 0.31 |

The crude referral proportion was defined as the total number of transplant referrals divided by the total number of patients with incident ESRD.

Referral Counts by Patient Case Mix.

Table 2 shows the differences in referral proportions by levels of the patient case mix. Older age, nonblack race, and women were consistently associated with lower referral counts over the study years, and patients with comorbid conditions (except hypertension) were less likely to be referred.

Table 2.

Kidney transplant referrals (percentages) by levels of patient case mix (risk factors) at the time of ESRD start among Georgia patients on dialysis from 2008 to 2011

| Case Mix Variables | 2008, n=557 (27%) | 2009, n=626 (29%) | 2010, n=651 (32%) | 2011, n=708 (34%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) group (%) | ||||

| 19–30 | 47 (50) | 54 (45) | 63 (62) | 34 (43) |

| 31–40 | 102(47) | 95 (49) | 102 (53) | 125(58) |

| 41–50 | 138 (33) | 153 (36) | 158 (42) | 174 (42) |

| 51–60 | 167 (24) | 192 (28) | 211 (31) | 234 (36) |

| 60+ | 103 (16) | 132 (19) | 117 (17) | 141 (20) |

| Race (%) | ||||

| Black | 387 (28) | 428 (30) | 455 (34) | 488 (37) |

| White | 157 (24) | 186 (26) | 179 (27) | 201 (29) |

| Other | 13 (38) | 12 (36) | 17 (53) | 19 (40) |

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Men | 344 (30) | 340 (29) | 388 (33) | 413 (36) |

| Women | 213 (23) | 286 (29) | 263 (31) | 295 (33) |

| BMI≥35 kg/m2 (%) | ||||

| Yes | 112 (24) | 148 (28) | 178 (35) | 197 (37) |

| No | 445 (28) | 478 (30) | 473 (31) | 511 (33) |

| Congestive heart failure (%) | ||||

| Yes | 121 (20) | 118 (21) | 132 (25) | 150 (27) |

| No | 436 (30) | 508 (32) | 519 (34) | 558 (37) |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease (%) | ||||

| Yes | 46 (19) | 50 (21) | 48 (22) | 37 (22) |

| No | 511 (28) | 576 (30) | 603 (33) | 671 (36) |

| Other cardiac disease (%) | ||||

| Yes | 57 (20) | 62 (25) | 59 (21) | 74 (25) |

| No | 500 (28) | 564 (30) | 592 (34) | 634 (36) |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | ||||

| Yes | 37 (16) | 39 (22) | 37 (20) | 34 (22) |

| No | 520 (28) | 587 (30) | 614 (33) | 674 (35) |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | ||||

| Yes | 35 (17) | 37 (18) | 29 (18) | 38 (23) |

| No | 522 (28) | 589 (30) | 622 (33) | 670 (35) |

| COPD (%) | ||||

| Yes | 21 (17) | 24 (16) | 19 (13) | 31 (22) |

| No | 536 (28) | 602 (30) | 632 (33) | 677 (35) |

| Hypertension (%) | ||||

| Yes | 495 (28) | 583 (30) | 583 (33) | 641 (35) |

| No | 62 (24) | 43 (20) | 68 (27) | 67 (28) |

| Diabetes (%) | ||||

| Yes | 295 (25) | 327 (27) | 346 (31) | 384 (32) |

| No | 262 (30) | 299 (32) | 305 (33) | 324 (37) |

| Tobacco use (%) | ||||

| Yes | 41 (21) | 48 (24) | 50 (29) | 62 (30) |

| No | 516 (28) | 578 (30) | 601 (32) | 646 (35) |

| Cancer (%) | ||||

| Yes | 11 (11) | 11 (10) | 15 (15) | 19 (17) |

| No | 546 (28) | 615 (30) | 636 (33) | 689 (35) |

| Nursing home status (%) | ||||

| No | 556 (28) | 625 (30) | 647 (34) | 701 (36) |

| Yes | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 6 (8) |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Risk-Adjusted Model for Referrals.

The stage 1 model of the two-stage Cox proportional hazards model indicated that age, race, sex, and patient comorbid conditions (except atherosclerotic heart disease and diabetes) were significantly associated with an increased likelihood of referral within 1 year of starting dialysis (Table 3). Blacks were 1.12 times more likely to be referred than whites in the first year (hazard ratio, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.24). Patients of older age, women, and those with the presence of comorbid conditions had a significantly lower referral. Additionally, there was a positive time trend, and the incidence of referral was significantly higher in 2011 compared with 2008 and 2009. Model AIC indicated that the adjusted model was a better fit than the crude model (AIC of 16,611.0 versus 17,297.7). In sensitivity analyses examining an extended 2-year follow-up, the model estimates of risk factors were not statistically different compared with the original model, and the Pearson correlation coefficient (r=0.96) indicated high agreement between the facility STReRs from both models (Supplemental Table 1). In sensitivity analyses including insurance status as an additional risk adjustment factor, patients with employer-based health insurance were more likely to be referred than patients with Medicare insurance (hazard ratio, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.55 to 2.00) (Supplemental Table 2), but facility STReRs were highly consistent (r=0.98).

Table 3.

Stage 1 Cox proportional hazard model estimates of patient case mix factors on referral for transplantation for data years 2008–2011

| Parameters | Referent Group | Coefficient | SEM | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) group | ||||

| 19–30 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 1.40 (1.18 to 1.66) | |

| 31–40 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.59) | |

| 51–60 | −0.22 | 0.06 | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.89) | |

| 60+ | 41–50 | −0.75 | 0.06 | 0.47 (0.42 to 0.53) |

| Race group | ||||

| Black | White | 0.12 | 0.05 | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.24) |

| Other | 0.22 | 0.14 | 1.25 (0.95 to 1.65) | |

| Men | Women | 0.13 | 0.04 | 1.14 (1.05 to 1.24) |

| Incident ESRD year | ||||

| 2008 | −0.30 | 0.06 | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.84) | |

| 2009 | −0.18 | 0.06 | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.94) | |

| 2010 | 2011 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.07) |

| BMI≥35 kg/m2 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.04) | |

| BMI unknown | BMI<35 kg/m2 | −0.51 | 0.15 | 0.60 (0.45 to 0.81) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | None | −0.16 | 0.05 | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.94) |

| Congestive heart failure unknown | None | −0.92 | 0.60 | 0.40 (0.12 to 1.30) |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | None | 0.00 | 0.09 | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.18) |

| Other cardiac disease | None | −0.14 | 0.07 | 0.87 (0.76 to 1.00) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | None | −0.27 | 0.09 | 0.77 (0.64 to 0.91) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | None | −0.24 | 0.09 | 0.79 (0.66 to 0.95) |

| COPD | None | −0.28 | 0.11 | 0.76 (0.61 to 0.94) |

| Hypertension | None | 0.23 | 0.07 | 1. 25 (1.09 to 1.44) |

| Diabetes | None | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.07) |

| Tobacco use | None | −0.21 | 0.08 | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.95) |

| Cancer | None | −0.71 | 0.14 | 0.49 (0.37 to 0.64) |

| Nursing home status | None | −2.14 | 0.32 | 0.12 (0.06 to 0.22) |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Sensitivity Analyses Calculating STReR among Small Dialysis Facilities.

Among the 72 facilities excluded due to annual incident n<5, classification of facilities was almost identical, except for small differences in the better/worse than expected category (Supplemental Table 3).

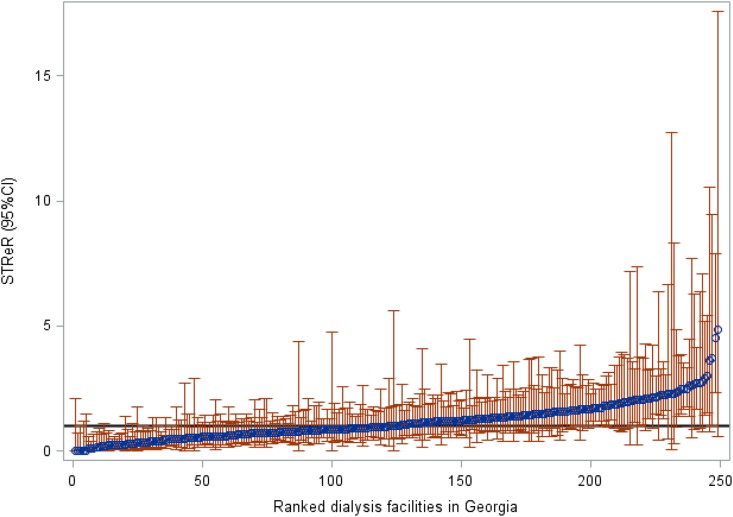

Rankings of facility-level STReRs (95% CI) over the 4-year period (2008–2011) are shown in Figure 1. Of the 249 facilities, 191 (77%) had STReRs not significantly different from one, 27 (11%) had STReRs significantly higher than one, and 31 (12%) had STReRs lower than one (Table 4). Compared with the remaining facilities, we found that the facilities with STReRs lower than expected were less likely to be for profit, were free standing, and were farther from the nearest transplant center. However, they were not different in terms of size or urban/rural classification (Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 1.

Ranked Standardized Transplant Ratios (STReRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) show actual referrals at Georgia dialysis facilities in reference to those expected for data years 2008–2011 (perfect agreement of observed and expected i.e. STReR=1 indicated in black).

Table 4.

Comparisons of the Standardized Transplant Referral Ratio classifications in an unadjusted model and a model adjusted for case mix for data years 2008–2011

| Model 1 (Unadjusted) | Model 2a (Adjusted for Case Mix) | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Better than Expected | As Expected | Worse than Expected | ||

| Better than expected (%) | 21 (8) | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 26 (10) |

| As expected (%) | 6 (2) | 185 (74) | 4 (2) | 195 (78) |

| Worse than expected (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 27 (11) | 28 (11) |

| Total (%) | 27 (11) | 191 (77) | 31 (12) | 249 |

Adjusted for patient case mix variables age, race, sex, incident year of ESRD, and comorbidities.

Comparison of Adjusted Versus Unadjusted Facility STReRs.

The estimated STReRs were classified into either the “as expected” category (i.e., not significantly different from one) or the “worse (better) than expected” category (i.e., significantly lower [higher] than one). A crossclassification table indicated 6% (n=16) disagreement between the STReRs from the two models (Table 4). Of those, seven facilities (3%) showed better performance after risk adjustment, and nine (3%) showed worse performance after risk adjustment.

Reliability

We found that the IUR values for the STReR range from 22% to 45% across the years 2008–2011. On average, this indicates a moderate degree of reliability (i.e., around 33% of the variability in STReRs can be attributed to between-facility variation, and 67% of the variability in STReRs can be attributed to within-facility variation).

Validity

Of the 2147 Georgia patients on incident dialysis in 2009, 626 (29%) were referred within 1 year, 341 (16%) were evaluated within 6 months, 238 (11%) were waitlisted within 1 year, and 50 (2%) were transplanted within 2 years of referral. The first year STReRs had significant positive correlations with crude facility referral proportions (r=0.96; P<0.001), transplant evaluation (r=0.46; P<0.001), waitlisting (r=0.35; P<0.001), and transplantation (r=0.20; P=0.004) proportions. Because a small percentage of transplants occurred within 2 years of referral (end of study period), computing the standardized transplant ratio was not feasible.

Discussion

The CMS and the kidney community have called for the development of quality measures for dialysis facility–based metrics to monitor quality, reduce variability in transplant access, and ultimately, improve equity in kidney transplantation (11,12,14). To date, dialysis facilities have only been evaluated on crude measures of transplant referral, such as in ESRD Network quality improvement projects to increase equitability in kidney transplantation (15), and no national quality metrics for dialysis facility transplant access currently exist. Our study shows that a risk-adjusted measure, the STReR, is a potentially valid and reliable metric that could be used as a clinical performance metric to evaluate kidney transplant access among dialysis facilities. These results underscore the importance of collecting national data on referral for transplantation to calculate quality metrics, such as the STReR.

We found that variation in referrals could be partially attributed to differences in baseline patient characteristics (e.g., demographic and clinical factors). However, after adjusting for patient case mix, considerable variance in STReRs persisted. Although we did not account for all patient characteristics, it is highly unlikely that patient case mix alone explains the total variation in transplant referrals. This suggests that a large part of observed variance in facility performance is due to dialysis facility–level factors versus variation in the patient pool. In addition, STReRs (versus crude measures of referrals) may be more effective when targeting lower-performing facilities for quality improvement initiatives. When targeting facilities with a specific patient pool (e.g., age/sex/race/comorbidity groups), the STReRs could also help identify and compare performances of dialysis facilities not performing as expected and inform where to target additional interventions.

Although the majority of dialysis facilities in Georgia seem to be performing as expected relative to the state, the current STReRs are not indicative of facility performance relative to the nation. On the basis of prior research findings that have reported substantial geographic variability in waitlisting and transplantation (2,19–23), we posit that facility STReRs are likely to substantially differ in other regions, which may have different patient characteristics and better transplantation outcomes. Although no other study has looked at a standardized measure of transplant referrals before, one study examining early steps to transplantation (e.g., facility-level medical suitability, interest in transplantation, and pretransplantation workup at dialysis facilities in the Midwest [Indiana, Ohio, and Kentucky]) found a similar distribution of facility performances (4). However, the scope of comparison is limited due to geographic differences. Likewise, because the STReRs are on the basis of pilot data, providing recommendations for official flagging of facilities by the CMS or other government or payer entities is challenging. Recommending a flagging criteria for facilities on the basis of the STReR will require a nationally representative cohort and a detailed methodology of classification with perhaps an extension to a Bayesian inferential framework, which is important future work.

To use STReR as a standardized measure of dialysis facility performance in a national setting, collection of national surveillance data on transplant referrals from the >5000 dialysis facilities in the United States is essential. Although a CMS expert review panel recommended collection of these data a decade ago, a national benchmark for collecting referral data on a national level has yet to be established (24). Most recently, development of other kidney transplant access measures, such as the Standardized First Kidney Transplant Waitlist Ratio for Incident Dialysis Patients and the Percentage of Prevalent Patients Waitlisted, were proposed by a CMS Technical Expert Panel but have not yet been submitted to the National Quality Forum (10). Although waitlisting outcomes are more attributable to dialysis facilities compared with transplantation, the use of waitlisting as a performance metric may still be problematic due to geographic variability in waitlisting practices across the United States that is beyond the control of dialysis facilities. Thus, the inclusion of referral for kidney transplantation evaluation as a quality metric may have more face validity and relevance to the dialysis facility leadership and staff responsible for educating patients and referring them to a kidney transplant center for medical evaluation.

There are a number of limitations to our study that should be noted when interpreting the proposed STReR measure. Similar to other indirectly standardized measures (e.g., Standardized Mortality Ratio and Standardized Hospitalization Ratio), the STReR compares the facility-level referrals with those adjusted for patient characteristics within the facility. Thus, one should be cautious about comparing performances of facilities, unless the underlying patient populations are similar. Our restriction of facility size to five or more patients with incident ESRD resulted in an exclusion of 72 smaller facilities, thereby limiting generalizability. Although a sensitivity analysis indicated minimal effects of exclusion on the other facility STReRs, new methodologic research is warranted on how to evaluate performance of small dialysis centers, and it is an important topic of future research. Also, although we risk adjusted for patients’ sociodemographic factors (e.g., race and sex) when calculating STReRs, we do acknowledge that their inclusion may mask disparities and inequalities in care (25,26). A sensitivity analysis indicated that exclusion of race and sex from patient case mix had minimal effect on the STReR estimates, and the classification of STReRs from the two models agreed in 99% of cases. We decided a priori not to consider any socioeconomic indicators, such as health insurance or neighborhood poverty, in the risk adjustment, because we did not believe that dialysis facilities should restrict access to referral on the basis of social factors that are associated with widespread disparities in transplant access (27). Our sensitivity analyses showed that patients with employer-based health insurance are more likely to be referred than those with Medicare, suggesting that socioeconomic status factors do play a role in referral for transplantation at dialysis facilities. A national conversation may be warranted to discuss whether it is appropriate to risk adjust for these variables before they are applied in practice. The STReR calculation does not account for referrals (<1% of all referrals) made to centers outside Georgia and is likely to be slightly underestimated. Finally, because our study is limited to Georgia, the case mix adjustment is relative to a regional patient population instead of the national ESRD population. National data collection on transplant referral data is needed to ensure generalizability of the STReR to all United States dialysis facilities.

We showed the potential of a new standardized quality measure of dialysis facility transplant performance, the STReR, on the basis of a pilot sample of >8000 patients on dialysis receiving treatment within 249 dialysis facilities in Georgia. Future implementation of transplant referral as a quality metric among dialysis facilities could allow ESRD policymakers and clinical providers to identify gaps in quality and access of care, encourage and/or incentivize dialysis providers to refer appropriate candidates for transplantation, and target evidence-based guidelines and interventions to increase access to kidney transplantation for patients receiving treatment within the dialysis facilities with the lowest performance.

Disclosures

S.O.P. is a minority shareholder of Fresenius Dialysis (College Park, GA). No other disclosures are reported.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grants R24MD008077 and U01MD01061 as well as Arnold Foundation grant PG007374.

The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. Some of the data reported here have been supplied by the US Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related Patient Voice, “Accountability of Dialysis Facilities in Transplant Referral: CMS Needs to Collect National Data on Dialysis Facility Kidney Transplant Referrals,” on pages 193–194.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04690417/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System : USRDS 2016 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashby VB, Kalbfleisch JD, Wolfe RA, Lin MJ, Port FK, Leichtman AB: Geographic variability in access to primary kidney transplantation in the United States, 1996-2005. Am J Transplant 7: 1412–1423, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patzer RE, Plantinga LC, Paul S, Gander J, Krisher J, Sauls L, Gibney EM, Mulloy L, Pastan SO: Variation in dialysis facility referral for kidney transplantation among patients with end-stage renal disease in Georgia. JAMA 314: 582–594, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR; Transplant Task Force of The Renal Network, Inc : Variation in access to kidney transplantation across dialysis facilities: Using process of care measures for quality improvement. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 824–831, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patzer RE, Plantinga L, Krisher J, Pastan SO: Dialysis facility and network factors associated with low kidney transplantation rates among United States dialysis facilities. Am J Transplant 14: 1562–1572, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plantinga L, Pastan S, Kramer M, McClellan A, Krisher J, Patzer RE: Association of U.S. Dialysis facility neighborhood characteristics with facility-level kidney transplantation. Am J Nephrol 40: 164–173, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders MR, Cagney KA, Ross LF, Alexander GC: Neighborhood poverty, racial composition and renal transplant waitlist. Am J Transplant 10: 1912–1917, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schold JD, Gregg JA, Harman JS, Hall AG, Patton PR, Meier-Kriesche HU: Barriers to evaluation and wait listing for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1760–1767, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J: Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 995–1002, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClellan WM, Plantinga LC, Wilk AS, Patzer RE: ESRD databases, public policy, and quality of care: Translational medicine and nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 210–216, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehgal AR: Should transplant referral be a clinical performance measure? J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 721–723, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kucirka LM, Purnell TS, Segev DL: Improving access to kidney transplantation: Referral is not enough. JAMA 314: 565–567, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NIH RePORTER Database: Reducing Racial Disparities in Access to Kidney Transplantation: The RADIANT Regional Study (U01MD010611), 2017. Available at https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=9251320&icde=36776274&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=4&csb=default&cs=ASC&pball=. Accessed March 28, 2017

- 14.Plantinga LC, Pastan SO, Wilk AS, Krisher J, Mulloy L, Gibney EM, Patzer RE: Referral for kidney transplantation and indicators of quality of dialysis care: A Cross-sectional Study. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 257–265, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patzer RE, Paul S, Plantinga L, Gander J, Sauls L, Krisher J, Mulloy LL, Gibney EM, Browne T, Zayas CF, McClellan WM, Arriola KJ, Pastan SO; Southeastern Kidney Transplant Coalition : A randomized trial to reduce disparities in referral for transplant evaluation. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 935–942, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patzer RE, Gander J, Sauls L, Amamoo MA, Krisher J, Mulloy LL, Gibney E, Browne T, Plantinga L, Pastan SO; Southeastern Kidney Transplant Coalition : The RaDIANT community study protocol: Community-based participatory research for reducing disparities in access to kidney transplantation. BMC Nephrol 15: 171, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahai H, Khurshid A: Confidence intervals for the mean of a Poisson distribution: A review. Biom J 35: 857–867, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 18.University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center: Report for the Standardized Transfusion Ratio, 2017. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/Restricted-STrR-Methodology-Report_June2017.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2017

- 19.Hall YN, Choi AI, Xu P, O’Hare AM, Chertow GM: Racial ethnic differences in rates and determinants of deceased donor kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 743–751, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patzer RE, Plantinga L, Basu M, Pastan SO: Geographic variation in access to kidney transplantation in the United States by Race. Presented at the World Transplant Congress, San Francisco, CA, July 26–31, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohan S, Mutell R, Patzer RE, Holt J, Cohen D, McClellan W: Kidney transplantation and the intensity of poverty in the contiguous United States. Transplantation 98: 640–645, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Axelrod DA, Lentine KL, Xiao H, Bubolz T, Goodman D, Freeman R, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Schnitzler MA: Accountability for end-stage organ care: Implications of geographic variation in access to kidney transplantation. Surgery 155: 734–742, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vranic GM, Ma JZ, Keith DS: The role of minority geographic distribution in waiting time for deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 14: 2526–2534, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sehgal AR, Leon J, Stark S: CMS2005. Developing Dialysis Facility-Specific Kidney Transplant Referral Clinical Performance Measures. The Renal Network, Inc. Indianapolis, IN, 2005

- 25.Iezzoni LI: Risk Adjustment for Measuring Healthcare Outcomes, 3rd Ed., Chicago, Health Administration Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krumholz HM, Brindis RG, Brush JE, Cohen DJ, Epstein AJ, Furie K, Howard G, Peterson ED, Rathore SS, Smith SC Jr., Spertus JA, Wang Y, Normand SL; American Heart Association; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Writing Group; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Stroke Council; American College of Cardiology Foundation : Standards for statistical models used for public reporting of health outcomes: An American heart association scientific statement from the quality of care and outcomes research interdisciplinary writing group: Cosponsored by the council on epidemiology and prevention and the stroke council. endorsed by the American college of cardiology foundation. Circulation 113: 456–462, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patzer RE, McClellan WM: Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 533–541, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.