Abstract

Background and objectives

Urinary ammonium excretion increases in response to nonvolatile acids to maintain normal systemic bicarbonate and pH. However, enhanced ammonia production promotes tubulointerstitial fibrosis in animal models. Therefore, a subset of individuals with CKD and normal bicarbonate may have acid-mediated kidney fibrosis that might be better linked with ammonium excretion than bicarbonate. We hypothesized that urine TGF-β1, as an indicator of kidney fibrosis, would be more tightly linked with urine ammonium excretion than serum bicarbonate and other acid-base indicators.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We measured serum bicarbonate and urinary ammonium, titratable acids, pH, and TGF-β1/creatinine in 144 persons with CKD. Multivariable-adjusted linear regression models determined the cross-sectional association between TGF-β1/creatinine and serum bicarbonate, urine ammonium excretion, urine titratable acids excretion, and urine pH.

Results

Mean eGFR was 42 ml/min per 1.73 m2, mean age was 65 years old, 78% were men, and 62% had diabetes. Mean urinary TGF-β1/creatinine was 102 (49) ng/g, mean ammonium excretion was 1.27 (0.72) mEq/h, mean titratable acids excretion was 1.14 (0.65) mEq/h, mean urine pH was 5.6 (0.5), and mean serum bicarbonate was 23 (3) mEq/L. After adjusting for eGFR, proteinuria, and other potential confounders, each SD increase of urine ammonium and urine pH was associated with a statistically significant 1.22-fold (95% confidence interval, 1.11 to 1.35) or 1.11-fold (95% confidence interval, 1.02 to 1.21) higher geometric mean urine TGF-β1/creatinine, respectively. Each SD increase of serum bicarbonate and urine titratable acids was associated with a nonsignificant 1.06-fold (95% confidence interval, 0.97 to 1.16) or 1.03-fold (95% confidence interval, 0.92 to 1.14) higher geometric mean urine TGF-β1/creatinine, respectively.

Conclusions

Urinary ammonium excretion but not serum bicarbonate is associated with higher urine TGF-β1/creatinine.

Keywords: chronic metabolic acidosis; chronic kidney disease; renal fibrosis; Humans; Male; Animals; Aged; creatinine; glomerular filtration rate; Bicarbonates; Ammonia; Ammonium Compounds; Linear Models; Cross-Sectional Studies; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Kidney Function Tests; proteinuria; diabetes mellitus; Transforming Growth Factors; Models, Animal; Hydrogen-Ion Concentration

Introduction

Chronic metabolic acidosis in CKD is a risk factor for CKD progression and mortality (1–5). There is biologic plausibility, however, that urine ammonium (NH4+) excretion may be a better acid-base indicator of risk than systemic bicarbonate. Kidney ammonia production with consequent NH4+ excretion is a central biologic response to nonvolatile acids that facilitate acid excretion, bicarbonate generation, and maintenance of normal systemic bicarbonate and pH. Although enhanced kidney ammonia production by residual nephrons is important to prevent acidosis in CKD, this compensatory per nephron increase in ammonia production promotes tubulointerstitial fibrosis through intrarenal activation of the alternative pathway of complement (6). Hence, enhanced NH4+ excretion to maintain normal systemic bicarbonate and pH may come at the expense of further kidney fibrosis, and a subset of persons with CKD and clinically normal acid-base status might still have acid-related kidney injury because of higher ammonia production.

We hypothesize that urine NH4+ is more tightly linked with kidney fibrosis than serum bicarbonate. The primary objective of this study was to determine the cross-sectional associations of urine NH4+ and serum bicarbonate with the kidney profibrotic marker urine TGF-β1 in persons with CKD (7,8). We selected urine TGF-β1 as the marker of interest, because it was reduced by oral alkali in patients with CKD, suggesting that it is a biomarker of acid-mediated organ injury (9). We also assessed the associations of urine TGF-β1 with urine titratable acids excretion and urine pH. We hypothesized that urine NH4+ excretion, but not the other acid-base indicators, would be positively associated with urine TGF-β1 in CKD. This hypothesis was tested in 144 persons with nondialysis-requiring CKD, in whom we measured urine TGF-β1, NH4+, titratable acids, pH, and serum bicarbonate.

Materials and Methods

Participant Characteristics

We evaluated 144 individuals with nondialysis-requiring CKD at the University of Utah and the Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Health Care System. One hundred are participants in an observational cohort study to determine the association between acid-base indicators, kidney injury, and physical function. Inclusion criteria were age older than 18 years old and stages 3 or 4 CKD. Exclusion criteria were presence of a chronic indwelling urinary catheter or history of chronic urinary tract infections. Forty-four are participants in a randomized interventional study comparing the effect of 6 months of oral sodium bicarbonate with that of placebo on urine TGF-β1 levels (NCT 01574157). Inclusion criteria are United States veterans older than 18 years old, type 1 or 2 diabetes, albuminuria ≥30 mg/g, stages 2–4 CKD, and normal serum bicarbonate concentration. Exclusion criteria are lean body weight >100 kg, use of oral alkali, serum potassium <3.5 mEq/L, use of five or more antihypertensive agents, BP>140/90 mmHg, congestive heart failure with New York Heart Association class 3 or 4 symptoms, significant fluid overload, factors judged to limit adherence, and chronic immunosuppressive therapy (10). Participants from the sodium bicarbonate study were included to broaden the range of CKD evaluated (stage 2 CKD) and increase statistical power. All participants were enrolled from December of 2012 to June of 2015, and baseline data from each study were analyzed. The studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Utah and the Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Healthcare System, and they were performed under the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurements

Trained research staff obtained demographic, comorbidity, medication, and laboratory data using standardized forms. BP was measured three times 1 minute apart after 5 minutes of quiet rest. The average was used in the analyses. GFR was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula (11). Participants collected a single 24-hour urine sample under mineral oil. Urine pH was measured using a pH meter. Urine NH4+ and titratable acids were measured using the formalin-titrimetric method (interassay coefficients of variation are 1.4% for NH4+ and 1% for titratable acids) (12,13). Titratable acids concentration (the main constituents are phosphate, creatinine, and uric acid) is first determined by mixing 10 ml of urine with 10 ml of 0.1 M hydrochloric acid to eliminate bicarbonate from the sample followed by titration to pH 7.4 with 0.1 M sodium hydroxide. Next, 10 ml of 8% formaldehyde is added to the sample, which forms hexamine and equimolar hydrochloric acid in the presence of ammonia. This is followed by titration with 0.1 M sodium hydroxide to urine pH 7.4. Dietary protein intake was calculated from urine urea nitrogen using the equation 6.25× [urine urea nitrogen + (weight ×0.031)] (14). Urine TGF-β1 was measured using the Human TGF-β1 Quantikine ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as previously described (15).

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are presented as means with SD unless otherwise specified. Categorical variables are presented as number with percentage. In descriptive analyses, participants were divided into tertiles of NH4+ excretion rate (milliequivalents per hour). Significance tests were performed using ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for dichotomous variables.

Multivariable linear regression analyses related the independent variables urine NH4+ excretion rate (in milliequivalents per hour and milliequivalents per kilogram per day), urine titratable acids excretion rate (in milliequivalents per hour and milliequivalents per kilogram per day), the sum of urine NH4+ and titratable acids excretion rate (in milliequivalents per hour and milliequivalents per kilogram per day), urine pH, serum bicarbonate, and acidosis status (acidosis was defined as bicarbonate <22 mEq/L) to the dependent variable urine TGF-β1/creatinine. TGF-β1/creatinine was right skewed; therefore, it was log transformed to better approximate a normal distribution. Because the units of the independent variables were different, we analyzed ΔTGF-β1/creatinine per 1-SD increase of each independent variable to better compare the strength of the relationship of each variable with log-transformed TGF-β1/creatinine. Models were adjusted for key clinical indicators, including age, sex, eGFR, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, diabetes status, systolic BP, body mass index (BMI), serum potassium, protein intake, and use of angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitors (ACE-is) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and/or alkali. BMI was not included in models in which the units of the independent variable included body weight. Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals are presented in their exponent form, representing geometric mean urine TGF-β1/creatinine fold change per SD increase. Similarly adjusted cubic spline regression models related each independent variable to the log-transformed urine TGF-β1–to-creatinine geometric mean ratio using the median value of each independent variable as the reference point.

The analyses were performed using Stata 14 (College Station, TX).

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Table 1 presents the cohort characteristics overall and by tertiles of NH4+ excretion. The cohort consisted of predominantly non-Hispanic whites, men, and participants with diabetes. The majority of participants had stage 3 or 4 CKD, and 78% were on ACE-i or ARB. Mean systolic BP was 125 mmHg, and 83% had systolic BP below 140 mmHg. In general, participants with higher NH4+ excretion were more likely to be men, more likely to have higher protein intake and eGFR, more likely to have lower serum potassium, and less likely to be taking alkali. There was a trend toward younger age with higher NH4+ excretion rate. Characteristics of participants by study are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics overall and by urine ammonium excretion rate tertiles

| Variable | Total Cohort, n=144 | NH4+ Tertile 1 (0.3–0.8 mEq/h), n=48 | NH4+ Tertile 2 (0.9–1.3 mEq/h), n=48 | NH4+ Tertile 3 (1.4–5.3 mEq/h), n=48 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 65 (13) | 68 (14) | 65 (12) | 62 (13) |

| Non-Hispanic white, no. (%) | 137 (95) | 46 (96) | 45 (94) | 46 (96) |

| Men, no. (%) | 112 (78) | 32 (67) | 36 (75) | 44 (92) |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 89 (62) | 30 (63) | 27 (56) | 32 (67) |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 115 (80) | 42 (88) | 34 (71) | 39 (81) |

| Coronary artery disease, no. (%) | 30 (21) | 8 (17) | 16 (33) | 6 (13) |

| Congestive heart failure, no. (%) | 13 (9) | 5 (10) | 3 (6) | 5 (10) |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 125 (16) | 124 (15) | 126 (15) | 127 (18) |

| Systolic BP <140 mmHg, no. (%) | 119 (83) | 43 (90) | 40 (83) | 36 (75) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 33 (8) | 32 (8) | 32 (6) | 34 (9) |

| Dietary protein intake, g/d | 81 (31) | 65 (21) | 77 (23) | 100 (36) |

| ACE-i/ARB use, no. (%) | 113 (78) | 40 (83) | 36 (75) | 37 (77) |

| Diuretic use, no. (%) | 73 (51) | 29 (60) | 25 (52) | 19 (40) |

| Alkali use, no. (%) | 25 (17) | 14 (29) | 7 (15) | 4 (8) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2, no. (%) | 42 (17) | 35 (15) | 40 (16) | 51 (16) |

| eGFR 60–89 | 20 (14) | 3 (6) | 6 (13) | 11 (23) |

| eGFR 45–59 | 41 (28) | 6 (13) | 14 (29) | 21 (44) |

| eGFR 30–44 | 45 (31) | 20 (42) | 13 (27) | 12 (25) |

| eGFR <30 | 38 (26) | 19 (40) | 15 (31) | 4 (8) |

| Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, mg/ga | 184 (48–576) | 176 (24–488) | 233 (50–570) | 181 (46–842) |

| Serum K+, mEq/L | 4.4 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.4 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.4) |

| Urine TGF-β1/creatinine, ng/g | 102 (49) | 103 (48) | 97 (44) | 107 (54) |

Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) unless noted otherwise, and categorical variables are presented as number (percentage). NH4+, ammonium; ACE-i, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Presented as median with interquartile range.

Acid-Base Measurements

Table 2 presents the acid-base measurements in the cohort and by tertiles of NH4+ excretion. Mean NH4+ excretion was 1.27 mEq/h, and mean bicarbonate was 23 mEq/L. Most participants had normal bicarbonate; however, 25% had bicarbonate <22 mEq/L. There was no clear relationship between NH4+ excretion and serum bicarbonate as a continuous or categorical variable. As expected, participants with higher NH4+ excretion also had higher titratable acids excretion, and mean urine acid excretion (NH4+ plus titratable acids) in the cohort was 0.59 mEq/kg body wt per day and 2.41 mEq/h. NH4+ excretion accounted for slightly more than one half of the total acid excretion. Few participants had urine pH ≥6.5, and NH4+ excretion was inversely associated with urine pH.

Table 2.

Acid-base measurements from serum and urine in the overall cohort and by urine ammonium excretion rate tertiles

| Acid-Base Measurement | Total Cohort, n=144 | NH4+ Tertile 1 (0.3–0.8 mEq/h), n=48 | NH4+ Tertile 2 (0.9–1.3 mEq/h), n=48 | NH4+ Tertile 3 (1.4–5.3 mEq/h), n=48 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | ||||

| NH4+, mEq/h | 1.27 (0.72) | 0.66 (0.14) | 1.11 (0.16) | 2.03 (0.74) |

| Titratable acid, mEq/h | 1.14 (0.65) | 0.66 (0.37) | 1.03 (0.42) | 1.72 (0.61) |

| NH4+ + titratable acid, mEq/h | 2.41 (1.27) | 1.32 (0.46) | 2.15 (0.47) | 3.75 (1.18) |

| NH4+, mEq/kg per day | 0.31 (0.16) | 0.18 (0.06) | 0.29 (0.07) | 0.47 (0.16) |

| Titratable acid, mEq/kg per day | 0.28 (0.15) | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.26 (0.10) | 0.40 (0.15) |

| NH4+ + titratable acid, mEq/kg per day | 0.59 (0.28) | 0.35 (0.13) | 0.55 (0.14) | 0.87 (0.27) |

| pH | 5.6 (0.5) | 5.8 (0.6) | 5.6 (0.5) | 5.4 (0.3) |

| pH≥6.5, no. (%) | 7 (5) | 5 (10) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Serum | ||||

| Bicarbonate, mEq/L | 23 (3) | 23 (2) | 23 (3) | 23 (3) |

| Bicarbonate <22 mEq/L, no. (%) | 36 (25) | 9 (19) | 15 (31) | 12 (25) |

| Bicarbonate 22–28 mEq/L, no. (%) | 106 (74) | 39 (81) | 32 (67) | 35 (73) |

| Bicarbonate >28 mEq/L, no. (%) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD), and categorical variables are presented as number (percentage). NH4+, ammonium.

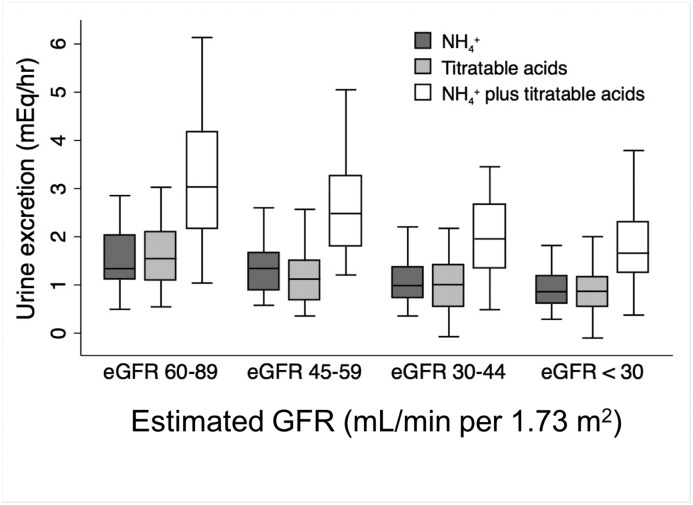

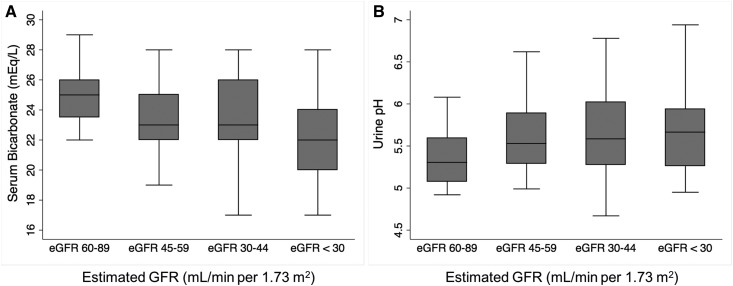

Figures 1 and 2 show values of the acid-base indicators across eGFR categories. As expected, urine NH4+ and titratable acids excretion and serum bicarbonate were lower with lower eGFR. There was no statistically significant difference in urine pH across the eGFR categories in this cohort.

Figure 1.

Urine acid excretion decreases with eGFR. P<0.001 for trend for each measure across eGFR categories.

Figure 2.

Serum bicarbonate decreases whereas urine pH is similar across eGFR categories. (A) Serum bicarbonate and (B) urine pH according to eGFR category. P=0.003 for trend for serum bicarbonate and P=0.05 for trend for urine pH.

Associations between Urinary TGF-β1 and Acid-Base Indicators

Table 3 presents the multivariable-adjusted associations between urine TGF-β1/creatinine and the acid-base indicators assessed. Each SD increase of NH4+ excretion was statistically significantly associated with 1.22-fold higher (for NH4+ expressed in milliequivalents per hour) or 1.20-fold higher (for NH4+ expressed in milliequivalents per kilogram per day) geometric mean TGF-β1/creatinine. There was no statistically significant relationship between urine titratable acids excretion and urine TGF-β1/creatinine. The sum of urine NH4+ and titratable acid excretion was directly associated with urine TGF-β1/creatinine but less so than urine NH4+ alone. Urine pH also was statistically significantly associated with 1.11-fold higher geometric mean TGF-β1/creatinine. Bicarbonate either as a continuous variable or categorized by acidosis status was not statistically significantly associated with urine TGF-β1/creatinine.

Table 3.

Association of urine TGF-β1/creatinine and the acid-base indicators after multivariable adjustment

| Acid-Base Measurement | SD of Acid-Base Measurement | Fold Difference in TGF-β1/Creatinine | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | |||

| NH4+, per SD ↑ | 0.72 mEq/h | 1.22 | 1.11 to 1.35 |

| Titratable acid, per SD ↑ | 0.65 mEq/h | 1.03 | 0.91 to 1.15 |

| NH4+ + titratable acid, per SD ↑ | 1.27 mEq/h | 1.15 | 1.03 to 1.30 |

| NH4+, per SD ↑ | 0.16 mEq/kg per daya | 1.20 | 1.09 to 1.32 |

| Titratable acid, per SD ↑ | 0.15 mEq/kg per daya | 1.03 | 0.92 to 1.14 |

| NH4+ + titratable acid, per SD ↑ | 0.28 mEq/kg per daya | 1.13 | 1.02 to 1.25 |

| pH, per SD ↑ | 0.5 | 1.11 | 1.02 to 1.21 |

| Serum | |||

| Bicarbonate, per SD ↑ | 3 mEq/L | 1.06 | 0.97 to 1.16 |

| Bicarbonate <22 versus ≥22 mEq/L | NA | 1.01 | 0.83 to 1.25 |

Models were adjusted for age; sex; eGFR; urine protein-to-creatinine ratio; diabetes; systolic BP; use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or alkali; body mass index; serum potassium; and protein intake. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NH4+, ammonium; NA, not applicable.

Body mass index was not adjusted for in these models.

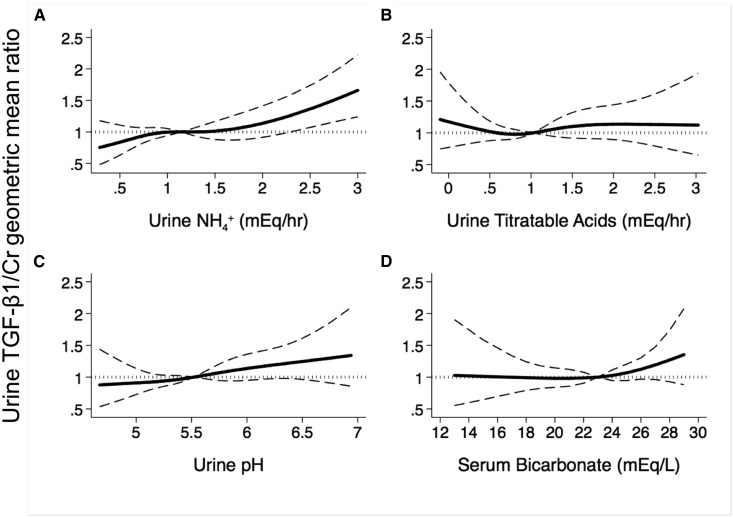

Figure 3 shows adjusted cubic spline regression plots of the association between urine TGF-β1/creatinine and the acid-base indicators using the median value of each as the reference. In each comparison, the associations were fairly linear, and urine NH4+ excretion and urine pH had a direct association with urine TGF-β1/creatinine. There was no significant relationship between urine TGF-β1/creatinine and urine titratable acids or serum bicarbonate.

Figure 3.

Urine ammonium excretion rate is directly associated with urine TGF-β1/creatinine. Adjusted cubic spline regression plots of the association between urine TGF-β1 (TGF-β1/creatinine [Cr]) and (A) urine ammonium (NH4+) excretion, (B) urine titratable acids excretion, (C) urine pH, and (D) serum bicarbonate. Shown on the ordinate of each panel is the ratio of the geometric mean urine TGF-β1/Cr to the geometric mean urine TGF-β1/Cr at the median value of each independent variable. Models are adjusted for eGFR, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, diabetes, body mass index, age, sex, systolic BP, serum potassium, dietary protein intake, and use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and/or alkali.

Because both urine NH4+ and urine pH directly associated with urine TGF-β1/creatinine, we included both terms in the multivariable regression model (Table 4). Although both had a statistically significant association with urine TGF-β1/creatinine after multivariable adjustment, each SD increase of NH4+ excretion and urine pH associated with 1.25- or 1.14-fold, respectively, higher geometric mean TGF-β1/creatinine in this model. Other factors with statistically significant associations with higher TGF-β1/creatinine included lower eGFR, lower protein intake, and women. There was a trend toward higher TGF-β1/creatinine among participants with diabetes compared with those without diabetes. There was no significant association between proteinuria, use of ACE-i/ARB, age, systolic BP, or BMI and TGF-β1/creatinine in this cohort to name a few (Table 4). Alkali use, which lowers NH4+ excretion and raises urine pH, was not associated with TGF-β1/creatinine in this model or a model that excluded NH4+ excretion rate and urine pH (fold change =0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 1.26).

Table 4.

Multivariable-adjusted associations between urine ammonium excretion, urine pH, and other clinical factors with urine TGF-β1/creatinine

| Variable | Fold Difference in TGF-β1/Creatinine | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Urine NH4+, mEq/h, per SD ↑ | 1.25 | 1.13 to 1.38 |

| Urine pH, per SD ↑ | 1.14 | 1.05 to 1.23 |

| GFR 60–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||

| Versus 45–59 | 1.32 | 1.01 to 1.73 |

| Versus 30–44 | 1.25 | 0.95 to 1.62 |

| Versus <30 | 1.42 | 1.05 to 1.92 |

| Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio <500 mg/g | ||

| Versus 500 to <1000 | 1.25 | 0.96 to 1.63 |

| Versus >1000 | 1.03 | 0.83 to 1.28 |

| Protein intake, g/d, per SD ↑ | 0.92 | 0.84 to 1.00 |

| Men versus women (reference) | 0.76 | 0.61 to 0.95 |

| Age, yr, per SD ↑ | 0.99 | 0.90 to 1.08 |

| Systolic BP < 120 mmHg | ||

| Versus 120–140 | 1.04 | 0.86 to 1.25 |

| Versus >140 | 1.22 | 0.95 to 1.58 |

| ACE-i/ARB use versus no (reference) | 0.93 | 0.76 to 1.13 |

| Diabetes versus no (reference) | 1.17 | 0.99 to 1.39 |

| Body mass index <25 kg/m2 | ||

| Versus 25 to <30 | 1.03 | 0.78 to 1.38 |

| Versus ≥30 | 0.90 | 0.68 to 1.19 |

| Alkali use versus no (reference) | 1.02 | 0.81 to 1.27 |

| Serum K+, mEq/L | 1.09 | 0.92 to 1.32 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NH4+, ammonium; ACE-i, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Discussion

We evaluated the association between acid-base indices and the kidney profibrotic marker urine TGF-β1 in persons with CKD. We did not identify an association between serum bicarbonate and urine TGF-β1. However, we identified significant direct correlations between urinary indices of acid-base regulation, specifically urine NH4+ excretion and urine pH, and urine TGF-β1. The magnitude of the relationship with urine TGF-β1 was stronger with urine NH4+ than urine pH, and the results were similar when NH4+ was evaluated as an hourly excretion rate or a daily excretion rate indexed to body weight. We did not observe an association between urine titratable acids excretion and TGF-β1. These results suggest that urine NH4+ excretion is more tightly linked with kidney fibrosis than systemic bicarbonate. We believe the direct association between urine NH4+ excretion and TGF-β1 is explained, at least in part, by high concentrations of intrarenal ammonia, subsequent activation of the alternative pathway of complement, and consequent kidney fibrosis as shown in animal models of CKD and hypokalemic nephropathy (6,16). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between urine NH4+ and kidney fibrosis markers in human CKD.

Because higher urine pH often indicates a more alkaline diet, which mitigates acid-mediated kidney injury (17,18), we were somewhat surprised to find an association between higher urine pH and higher urine TGF-β1 in this cohort. This association, however, may still be linked with ammonia-mediated kidney injury, because each unit higher urine pH corresponds with a tenfold higher NH3:NH4+. This is important, because the mechanism by which ammonia activates the alternative pathway of complement is by nucleophilic disruption of the internal thioester bond of the complement protein C3 by lone electron pairs on NH3 (19). This disruption is not likely to occur with NH4+, because electron pairs are unavailable for nucleophilic disruption. Hence, the direct association between urine pH and TGF-β1 may be because of a higher ratio of NH3 to NH4+ in the kidney, although this is speculative. Another possible reason why urine pH had a direct correlation with TGF-β1 is because TGF-β1 reduces aldosterone activity in the distal nephron, which would consequently reduce distal H+ secretion (20). Finally, higher urine pH may simply be an indicator of impaired tubular H+ secretion that coexists with a greater degree of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Irrespective of potential mechanisms, higher urine pH in CKD may be a sign of tubulointerstitial fibrosis.

Apart from urine NH4+ and urine pH, other factors that associated with higher urine TGF-β1 after multivariable adjustment included lower eGFR and women. Although the association with lower eGFR is not surprising, we are not aware of significant sex differences related to urine TGF-β1 levels in CKD. Higher intrarenal TGF-β1 may partly explain why women have a higher prevalence of CKD and diabetic kidney disease than men (21,22); however, sex differences regarding urine TGF-β1 in CKD require confirmation. Protein intake had an inverse association with urine TGF-β1 after multivariable adjustment, despite there being a direct relationship with urine NH4+ excretion. This suggests a tighter link between NH4+ and TGF-β1 than protein intake and TGF-β1. In addition, participants with diabetes had a trend toward higher urine TGF-β1. There was also a trend toward higher urine TGF-β1 with systolic BP >140 mmHg. A stronger relationship with higher systolic BP might not have been observed, because most participants had well controlled systolic BP and because lowering systolic BP reduces urine TGF-β1 (23). Although ACE-i/ARB use was not associated with TGF-β1, nearly 80% of the cohort was prescribed ACE-i/ARB, which also lowers urine TGF-β1 in CKD (24,25). We did not observe a consistent relationship between urine TGF-β1 and proteinuria in this cohort. Nevertheless, urine NH4+ excretion had a strong association with urine TGF-β1 in this cohort after adjustment for these potential confounders, an observation that should be confirmed in other cohorts.

Although our results suggest that higher urine NH4+ excretion associates with greater kidney fibrosis in CKD, we and others have found that lower urine NH4+ excretion is associated with higher risk of poor kidney and survival outcomes during long-term follow-up (26–28). For example, the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension participants with NH4+ excretion below 15 mEq/d had 46% higher risk of death or ESRD than if NH4+ excretion was >24 mEq/d. However, there was a suggestion of a U-shaped relationship, with the lowest risk of death or ESRD if urine NH4+ excretion was 30–40 mEq/d (26). More specifically, the slope between urine NH4+ and risk of death or ESRD was steeper below this range than the slope above this range. We hypothesize that, although higher kidney ammonia production and consequently, higher urine NH4+ excretion may promote kidney fibrosis, higher NH4+ excretion is also a sign that kidney tubules can produce and excrete ammonia in an effort to maintain normal bicarbonate and pH. Although lower NH4+ excretion may signal less TGF-β1–associated kidney injury, it is also an indicator of impaired tubule function, leading to interstitial acid retention (29,30) and increased risk of overt metabolic acidosis (26). We posit that this consequently augments other mechanisms of acid-mediated kidney injury (29–33), which on a background of impaired tubule function, leads to a risk of kidney failure that exceeds the risk observed with higher levels of ammonia production. Overall, urine NH4+ may reflect different states of kidney health and consequently, different levels of risk in CKD.

Our results may have important implications regarding how alkaline therapy is currently used in CKD. Clinical practice guidelines recommend maintaining serum bicarbonate at a minimum of 22 mEq/L to ameliorate negative effects of acidosis on bone and protein (34). Results from several single-center studies suggest that alkaline therapy has potential kidney benefits as well, even among those without overt acidosis, and several ongoing trials are testing the pleiotropic effects of alkaline therapy in CKD in this setting (9,17,18,35–38). The results of this study support the notion that alkaline therapy may be indicated for the broader CKD population rather than only those with overt metabolic acidosis. For example, alkaline therapy might preserve kidney function among those with high NH4+ excretion by mitigating TGF-β1–mediated kidney fibrosis. However, alkaline therapy might also be beneficial for those with normal serum bicarbonate and low urine NH4+ excretion, because they are at higher risk of overt acidosis and poor long-term outcomes (26–28). Whether urine NH4+ measurements can better help guide the clinical use of alkaline therapy for the purpose of improving clinical outcomes in CKD should be determined.

A strength of this study is that we measured urine indicators of acid-base regulation in addition to serum bicarbonate. We also a priori selected TGF-β1 as the primary outcome of interest. Our cohort consisted of participants with a high prevalence of systolic BP <140 mmHg (83%) and treatment with ACE-i/ARB (78%). Hence, the associations between the acid-base indicators and TGF-β1 were observed in a cohort with a high proportion receiving standard of care. Nevertheless, our cohort consisted of predominantly non-Hispanic whites, men, and individuals with diabetes. Whether our results are generalizable to other populations should be determined. This was a cross-sectional analysis of the relationships between several acid-base indicators and urine TGF-β1; how these relationships change over time are uncertain. As such, we can only infer association rather than causation, and residual confounding may still be present. Nevertheless, alkali, which lowers kidney ammonia production, reduced urine TGF-β1 in patients with CKD and acidosis, supporting ammonia as the cause and TGF-β1 as the effect in our study (9). We did not measure systemic pH; however, it is unlikely that an association between systemic pH and urine TGF-β1 would have been observed, because there was no relationship with systemic bicarbonate. We did not measure urine bicarbonate; however, it is likely that it would have been undetectable in most participants, because only seven had urine pH ≥6.5.

In summary, urine NH4+ excretion has a strong and direct association with the kidney profibrotic marker urine TGF-β1 independent of eGFR, proteinuria, protein intake, diabetes status, and other potential confounders in persons with CKD. These results are consistent with the findings in animal models that high kidney ammonia production promotes kidney fibrosis. Urine pH also had a direct relationship with urine TGF-β1. Serum bicarbonate and urine titratable acids were not associated with urine TGF-β1. These data suggest that kidney ammonia production and NH4+ excretion are more tightly linked with kidney fibrosis than systemic acid-base status in CKD.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by Career Development award IK2 CX000537 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development award).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07510717/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dobre M, Yang W, Chen J, Drawz P, Hamm LL, Horwitz E, Hostetter T, Jaar B, Lora CM, Nessel L, Ojo A, Scialla J, Steigerwalt S, Teal V, Wolf M, Rahman M; CRIC Investigators : Association of serum bicarbonate with risk of renal and cardiovascular outcomes in CKD: A report from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 670–678, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Association of serum bicarbonate levels with mortality in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1232–1237, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raphael KL, Wei G, Baird BC, Greene T, Beddhu S: Higher serum bicarbonate levels within the normal range are associated with better survival and renal outcomes in African Americans. Kidney Int 79: 356–362, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raphael KL, Zhang Y, Wei G, Greene T, Cheung AK, Beddhu S: Serum bicarbonate and mortality in adults in NHANES III. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 1207–1213, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah SN, Abramowitz M, Hostetter TH, Melamed ML: Serum bicarbonate levels and the progression of kidney disease: A cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 270–277, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nath KA, Hostetter MK, Hostetter TH: Pathophysiology of chronic tubulo-interstitial disease in rats. Interactions of dietary acid load, ammonia, and complement component C3. J Clin Invest 76: 667–675, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Böttinger EP: TGF-beta in renal injury and disease. Semin Nephrol 27: 309–320, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu L, Border WA, Huang Y, Noble NA: TGF-beta isoforms in renal fibrogenesis. Kidney Int 64: 844–856, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phisitkul S, Khanna A, Simoni J, Broglio K, Sheather S, Rajab MH, Wesson DE: Amelioration of metabolic acidosis in patients with low GFR reduced kidney endothelin production and kidney injury, and better preserved GFR. Kidney Int 77: 617–623, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US National Library of Medicine: Investigations of the Optimum Serum Bicarbonate Level in Renal Disease, 2017. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01574157. Accessed September 29, 2017

- 11.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro III AF, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunarro JA, Weiner MW: A comparison of methods for measuring urinary ammonium. Kidney Int 5: 303–305, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan JC: The rapid determination of urinary titratable acid and ammonium and evaluation of freezing as a method of preservation. Clin Biochem 5: 94–98, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maroni BJ, Steinman TI, Mitch WE: A method for estimating nitrogen intake of patients with chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 27: 58–65, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis D, Forrest KY, Erbey J, Orchard TJ: Urinary measurement of transforming growth factor-beta and type IV collagen as new markers of renal injury: Application in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Chem 44: 950–956, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolins JP, Hostetter MK, Hostetter TH: Hypokalemic nephropathy in the rat. Role of ammonia in chronic tubular injury. J Clin Invest 79: 1447–1458, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo C, Wesson DE: Dietary acid reduction with fruits and vegetables or bicarbonate attenuates kidney injury in patients with a moderately reduced glomerular filtration rate due to hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int 81: 86–93, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE: A comparison of treating metabolic acidosis in CKD stage 4 hypertensive kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or sodium bicarbonate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 371–381, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark EC, Nath KA, Hostetter MK, Hostetter TH: Role of ammonia in tubulointerstitial injury. Miner Electrolyte Metab 16: 315–321, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husted RF, Matsushita K, Stokes JB: Induction of resistance to mineralocorticoid hormone in cultured inner medullary collecting duct cells by TGF-beta 1. Am J Physiol 267: F767–F775, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu MK, Lyles CR, Bent-Shaw LA, Young BA; Pathways Authors : Risk factor, age and sex differences in chronic kidney disease prevalence in a diabetic cohort: The pathways study. Am J Nephrol 36: 245–251, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertoluci MC, Uebel D, Schmidt A, Thomazelli FC, Oliveira FR, Schmid H: Urinary TGF-beta1 reduction related to a decrease of systolic blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes and clinical diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 72: 258–264, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park HC, Xu ZG, Choi S, Goo YS, Kang SW, Choi KH, Ha SK, Lee HY, Han DS: Effect of losartan and amlodipine on proteinuria and transforming growth factor-beta1 in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1115–1121, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Praga M, Andrade CF, Luño J, Arias M, Poveda R, Mora J, Prat MV, Rivera F, Galceran JM, Ara JM, Aguirre R, Bernis C, Marín R, Campistol JM: Antiproteinuric efficacy of losartan in comparison with amlodipine in non-diabetic proteinuric renal diseases: A double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1806–1813, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raphael KL, Carroll DJ, Murray J, Greene T, Beddhu S: Urine ammonium predicts clinical outcomes in hypertensive kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2483–2490, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scialla JJ, Asplin J, Dobre M, Chang AR, Lash J, Hsu CY, Kallem RR, Hamm LL, Feldman HI, Chen J, Appel LJ, Anderson CA, Wolf M; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study Investigators : Higher net acid excretion is associated with a lower risk of kidney disease progression in patients with diabetes. Kidney Int 91: 204–215, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallet M, Metzger M, Haymann JP, Flamant M, Gauci C, Thervet E, Boffa JJ, Vrtovsnik F, Froissart M, Stengel B, Houillier P; NephroTest Cohort Study group : Urinary ammonia and long-term outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 88: 137–145, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wesson DE, Jo CH, Simoni J: Angiotensin II receptors mediate increased distal nephron acidification caused by acid retention. Kidney Int 82: 1184–1194, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wesson DE, Jo CH, Simoni J: Angiotensin II-mediated GFR decline in subtotal nephrectomy is due to acid retention associated with reduced GFR. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 762–770, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farwell WR, Taylor EN: Serum anion gap, bicarbonate and biomarkers of inflammation in healthy individuals in a national survey. CMAJ 182: 137–141, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickering WP, Price SR, Bircher G, Marinovic AC, Mitch WE, Walls J: Nutrition in CAPD: Serum bicarbonate and the ubiquitin-proteasome system in muscle. Kidney Int 61: 1286–1292, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schindler R: Causes and therapy of microinflammation in renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19[Suppl 5]: V34–V40, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 42[4 Suppl 3]: S1–S201, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Brito-Ashurst I, Varagunam M, Raftery MJ, Yaqoob MM: Bicarbonate supplementation slows progression of CKD and improves nutritional status. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2075–2084, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE: Treatment of metabolic acidosis in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or oral bicarbonate reduces urine angiotensinogen and preserves glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int 86: 1031–1038, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahajan A, Simoni J, Sheather SJ, Broglio KR, Rajab MH, Wesson DE: Daily oral sodium bicarbonate preserves glomerular filtration rate by slowing its decline in early hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int 78: 303–309, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raphael KL: Approach to the treatment of chronic metabolic acidosis in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 696–702, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.