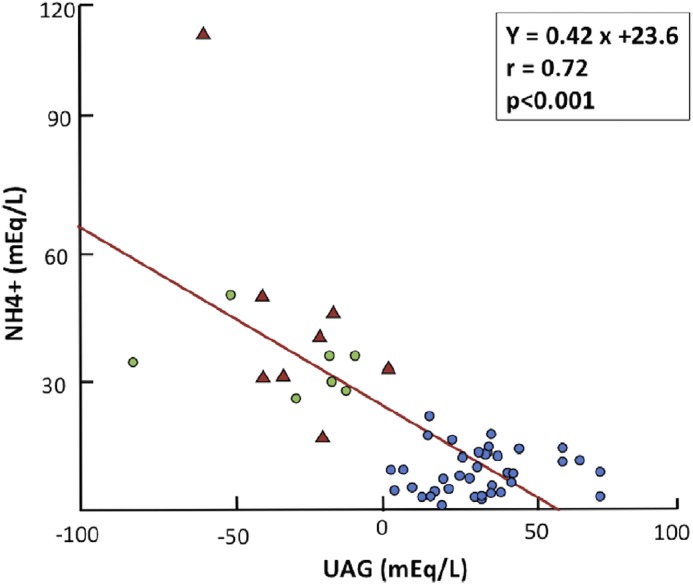

From its introduction in the late 1980s, the urine anion gap (UAG), calculated as [(Na+ + K+) – (Cl−)] has been used to roughly estimate whether urine ammonium is increased or decreased in the evaluation of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis (1,2). This is the context in which the use of the UAG can be very helpful at the bedside when urine ammonium is not available. The concept stems from the strong relationship between UAG and urine ammonium excretion in patients with metabolic acidosis induced by ammonium chloride administration, a potent stimulus for ammonium excretion (1). That is to say, the more ammonium in the urine, the lower the UAG is, which achieves negative values within a wide range (0 to −200 mEq/L) during hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. In patients with distal renal tubular acidosis (RTA) of several etiologies, the UAG is positive, despite the prevailing metabolic acidosis, and this is a useful bedside diagnostic index of impaired ammonium excretion (2) (Figure 1). In all types of distal RTA, whether hereditary or acquired, the UAG remains positive, because impaired hydrogen ion secretion leads to reduced ammonium excretion, the capital feature of distal RTA (3,4). It is important to know the effect of CKD on the UAG, however, because some patients with distal RTA, usually those with hyperkalemic forms, have reduced GFR (5).

Figure 1.

Urinary ammonium (NH4+) excretion in relation to urinary anion gap (UAG) for 38 patients with different types of distal renal tubular acidosis (blue circles), seven apparently healthy individuals receiving ammonium chloride (green circles), and eight patients with hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis associated with diarrhea (red triangles). Reprinted from ref. 6, with permission.

The UAG, like the plasma anion gap, serves mainly to identify an abnormal ion suspected to be either present in excessive quantities or inappropriately low for a given clinical setting. It should be used in the context of evaluating someone who presents with a low level of plasma bicarbonate caused by either metabolic acidosis or chronic respiratory alkalosis (6). Hypobicarbonatemia and hyperchloremia are features of both chronic respiratory alkalosis and hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. Physicians sometimes make the incorrect assumption that the patient has hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis until the arterial blood gas reveals the proper diagnosis. Unlike in hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, in chronic respiratory alkalosis, the UAG is increased (positive), reflecting low ammonium excretion, which is an appropriate compensatory response to the prevailing alkalemia (6). Outside the setting of evaluating someone with low plasma bicarbonate levels, there is no point in using the UAG, and even then, there are several caveats and limitations that were pointed out from the beginning (1,2): namely that the relationship between UAG and ammonium would be disturbed if the urine contains ketoanions, bicarbonate, or any other unusual compounds that were anionic or cationic. For example, high urine lithium levels would decrease the UAG (i.e., make it negative), whereas the presence of ketoanions would increase it and tend to make it positive. The latter situation, however, is complex, because the metabolic acidosis caused by ketoacidosis enhances ammonium excretion. That is, acidosis augments the excretion of an unmeasured cation (UC; urinary ammonium [NH4+]), and therefore, the UAG decreases. At the same time, however, the presence of ketoanions has the opposite effect on the UAG, such that it may not be as negative as expected from the high NH4+ content.

All of this is best seen by appreciating that the UAG formula UAG = [(Na+ + K+) − (Cl−)] actually reflects the difference between all unmeasured anions (UAs) and UCs (2,6). The principle of electroneutrality dictates that the sum of all anions and all cations present in the urine, like in plasma, should be equal (Equation 1). The UAs in urine are those that are not routinely measured are sulfate, phosphate, and organic anions. UCs in urine are NH4+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. Consistent with this principle, in a 24-hour urine collection, the sum of the excretions of sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and ammonium equaled the sum of the excretions of chloride, phosphate, sulfate, and organic anions (7). Therefore, the sum of routinely measured anions (Cl− and HCO3−) and cations (Na+ and K+) plus those anions and cations not routinely measured has to be the same:

| (1) |

This formula can be re-expressed as follows:

| (2) |

UHCO3− can be considered negligible at urine pH <6.6, and therefore, bicarbonate can be deleted from the UAG formula. This is done, because urine bicarbonate is usually not measured by clinical laboratories but can be easily calculated from the urine pH (8):

| (3) |

Thus,

| (4) |

It is Equation 4 that best describes how the UAG can be affected by changing UA, UC, or both. A large change in NH4+ will affect the UAG and decrease it. By how much? There are no normal UAG values because of the wider range of the UAG. The UAG should be largely negative, because ammonium increases about two- to fivefold during metabolic acidosis (1,2). An ideal clinical setting is one where only ammonium is expected to be increased (for instance, metabolic acidosis caused by diarrhea with normal kidney function). Here, the UAG decreases markedly and is largely negative (2). The other setting is distal RTA, where urine ammonium cannot increase owing to impaired H+ secretion and the UAG remains positive, despite metabolic acidosis as noted above. If the concentrations of other cations or anions are altered concurrently, there is also an effect on the UAG that must be taken into account. In the absence of confounding variables, the UAG does discriminate well if the kidney response in terms of ammonium excretion is appropriate or not in someone who has a low level of plasma bicarbonate.

But what if the patient has impaired GFR? This is the question that is often posed by residents and fellows during clinical rounds. At what level of CKD is the ability to excrete ammonium limited, such that the inverse correlation with the UAG is not present, despite the presence of metabolic acidosis? Are there concomitant alterations in other unmeasured ions, in the setting of CKD, that further compound the interpretation of the UAG? Until now, there was limited information from large clinical studies to support the otherwise pathophysiologically sound conclusion that, in the setting of CKD, the UAG is affected by both inability to produce urine NH4+ and concurrent changes in UAs that preclude its clinical use. In this issue, Raphael et al. (9) have examined the correlation between the UAG and urine ammonium using data collected from a cohort of patients with hypertension and CKD participating in the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension. Four parameters were evaluated in regard to their correlation with urine ammonium: the UAG, the UAG with the inclusion of urine phosphate, the UAG with the inclusion of urine sulfate, and the UAG with the inclusion of urine phosphate and sulfate. Participants were categorized into three groups by tertiles of UAG and daily urine ammonium. Overall, in this CKD population, the UAG had a weak and direct (not indirect) correlation with urine ammonium (r=0.18; P≤0.001). This should not be a surprise, because the ability to excrete ammonium is markedly curtailed with decreased kidney function. In addition, confounding variables related to concurrent alterations in UAs, namely sulfate and phosphate, further interfere with the UAG-ammonium relationship in CKD. In keeping with this expectation, a significant inverse correlation was found between the corrected UAG (the UAG with the inclusion of urine phosphate and sulfate) and urine ammonium (r=−0.58; P≤0.001). If these patients had metabolic acidosis or had been given ammonium chloride to stimulate acid excretion, the inverse correlation may have improved further but not by much, because in advanced CKD, an increase in the excretion of ammonium is severely limited. Reduced nephron number, increasing plasma potassium, and reduced aldosterone (often because of medications, such as renin angiotensin system blockers) all limit the ability to excrete ammonium in CKD, even in the presence of acidosis. In addition, sulfate and phosphate in the urine change in CKD and may be decreased as in the study by Raphael et al. (9). Measurement of these anions would add to the work flow and render it too cumbersome in clinical practice as pointed out by Raphael et al. (9). Therefore, there is little practical value for the use of a corrected UAG in the setting of CKD.

Another objective of the study by Raphael et al. (9) was to examine if UAG, as a surrogate of urine ammonium, was associated with risk of ESKD or death. This was a follow-up of their previous study reporting that these outcomes are poorer in patients with CKD and low NH4+ (10). Because urine ammonium falls as GFR declines, one could also conclude that it is not a better marker than a low GFR by itself. However, reduced urine ammonium may provide some pathophysiologic insight in CKD progression, and direct measurements are of interest. Given all of the limitations of using the UAG during CKD just outlined, it is no surprise that it failed to predict risk of ESKD or death (9). Although urine ammonium is not generally measured by the majority of hospitals in the United States, it can actually be measured using the methodology used routinely for measurement of plasma ammonium that is done by autoanalyzer or direct enzymatic methods. In the proper context, however, the UAG remains a useful tool at the bedside to roughly estimate whether ammonium excretion is either markedly increased or markedly decreased in patients who present with a low plasma bicarbonate. The absence of acute kidney disease or CKD is a necessary requirement for a meaningful interpretation of the UAG.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Robert Rosa for the careful reading of this editorial and his suggestions.

D.B. received grant support from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant R01 DK-104785.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related article, “Urine Anion Gap to Predict Urine Ammonium and Related Outcomes in Kidney Disease,” on pages 205–212.

References

- 1.Goldstein MB, Bear R, Richardson RM, Marsden PA, Halperin ML: The urine anion gap: A clinically useful index of ammonium excretion. Am J Med Sci 292: 198–202, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batlle DC, Hizon M, Cohen E, Gutterman C, Gupta R: The use of the urinary anion gap in the diagnosis of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. N Engl J Med 318: 594–599, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batlle D, Haque SK: Genetic causes and mechanisms of distal renal tubular acidosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3691–3704, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palazzo V, Provenzano A, Becherucci F, Sansavini G, Mazzinghi B, Orlandini V, Giunti L, Roperto RM, Pantaleo M, Artuso R, Andreucci E, Bargiacchi S, Traficante G, Stagi S, Murer L, Benetti E, Emma F, Giordano M, Rivieri F, Colussi G, Penco S, Manfredini E, Caruso MR, Garavelli L, Andrulli S, Vergine G, Miglietti N, Mancini E, Malaventura C, Percesepe A, Grosso E, Materassi M, Romagnani P, Giglio S: The genetic and clinical spectrum of a large cohort of patients with distal renal tubular acidosis. Kidney Int 91: 1243–1255, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batlle DC, Arruda JA, Kurtzman NA: Hyperkalemic distal renal tubular acidosis associated with obstructive uropathy. N Engl J Med 304: 373–380, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batlle D, Chin-Theodorou J, Tucker BM: Metabolic acidosis or respiratory alkalosis? Evaluation of a low plasma bicarbonate using the urine anion gap. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 440–444, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemann J Jr., Litzow JR, Lennon EJ: The effects of chronic acid loads in normal man: Further evidence for the participation of bone mineral in the defense against chronic metabolic acidosis. J Clin Invest 45: 1608–1614, 1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batlle D, Saleem K, Nithin R: The use of bedside urinary parameters in the evaluation of Metabolic Acidosis. In: Metabolic Acidosis, edited by Wesson D, New York, Springer Science, 2016, pp 39–51 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raphael KL, Gilligan S, Ix JH: Urine anion gap to predict urine ammonium and related outcomes in kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 205–212, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raphael KL, Carroll DJ, Murray J, Greene T, Beddhu S: Urine ammonium predicts clinical outcomes in hypertensive kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2483–2490, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]