Introduction

Hemodialysis vascular access is the “lifeline” for patients on hemodialysis. Unfortunately, because of its poor patency and significant complication rate, it is also the “Achilles heel” of hemodialysis. For example, the current unassisted arteriovenous fistula (AVF) maturation rate is only 40% between 6 and 9 months, and the 1-year unassisted patency for polytetrafluoroethylene grafts is 23%. Despite the magnitude of the clinical problem, relatively few new and effective therapies have been introduced into this field over the last two decades, resulting in a stagnation of vascular access care. We believe that an important barrier to developing new and effective therapies is the current lack of consensus among the different vascular access stakeholder groups (information on project structure below) regarding acceptable clinical trial end points for vascular access trials. Achieving such a consensus would result in a better defined product development pathway, which is a critical step to stimulate development by academic and commercial entities of new drugs, devices, biologics, and processes of care for vascular access dysfunction.

The Kidney Health Initiative (KHI) is a public-private partnership between the American Society of Nephrology and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to promote innovation and patient safety in the field of kidney disease. The KHI aims to achieve this goal by initiating projects with output (white papers, data standards, workshops, and roadmaps) that better defines the product development and regulatory pathway for safe and effective kidney disease treatments (1,2). We believe that evidence-based consensus among all involved stakeholder groups regarding vascular access clinical trial end points will serve as an important catalyst for interest, innovation, and investment in the field of vascular access through the creation of well defined clinical and regulatory pathways in this area. This will hopefully then result in novel, safe, and effective therapies for vascular access dysfunction, which would allow us to take better care of our patients on hemodialysis.

This manuscript is the first in a four-paper series, and it serves to introduce the project. The second manuscript by Beathard et al. (3) describes clinical trial end points for arteriovenous dialysis access, whereas the third manuscript by Allon et al. (4) describes clinical trial end points for dialysis catheters. Finally, the fourth manuscript by Hurst et al. (5) is an FDA commentary on the first three manuscripts. Our hope is that this quartet of manuscripts will facilitate a more well defined clinical trial pathway for testing out novel therapies for vascular access.

Project Structure

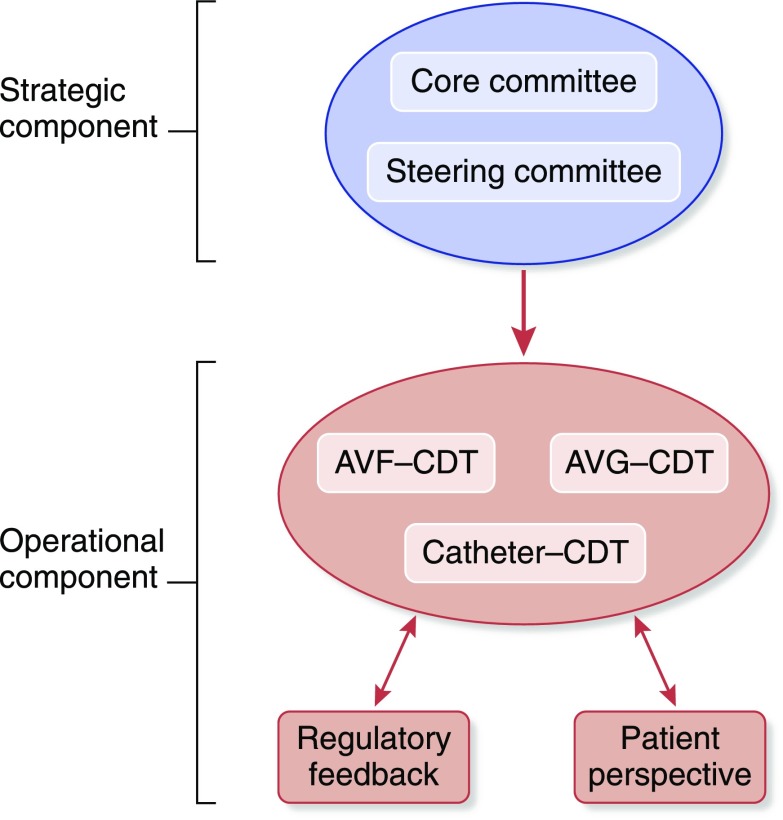

The organizational structure of this KHI project included strategic and operational components (Figure 1). The strategic component was made up of a small core committee, which was responsible for overall leadership and strategy for the project, together with a larger steering committee that allowed for broad representation from the vascular access community (surgeons [general, transplant, and vascular], nephrologists, interventionalists [radiologists, nephrologists, and surgeons], nurses, patients, international advisors, and industry partners). The operational component was divided initially into three content development teams (CDTs) that were tasked with identifying clinical trial end points for AVFs, arteriovenous grafts (AVGs), and tunneled dialysis catheters (catheters). At the end of the project, the outputs from the AVF and AVG teams were merged into a single manuscript defining clinical trial end points for arteriovenous access (3). Additional stakeholders included the KHI Patient and Family Partnership Council (PFPC) as well as FDA (Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; Center for Device and Radiological Health) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) representation.

Figure 1.

Organizational structure of the kidney Health Initiative: Vascular access clinical trial endpoints project. Strategic and operational components, the three content development teams (CDTs) opportunity for regulatory feedback and patient perspectives. AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, Arteriovenous graft.

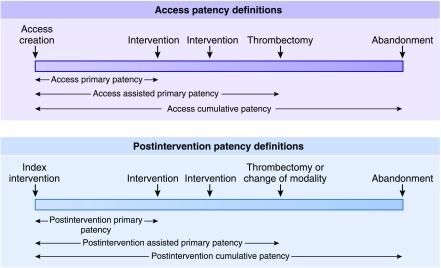

Figure 2.

Temporal vascular access patency definitions. The upper panel describes patency definitions after placement of the primary access, whereas the lower panel does the same after an intervention (please review in conjunction with Table 1).

Multidisciplinary Approach

As with all KHI projects, an important strength of this initiative was its access to a diverse breadth and depth of expertise through the KHI’s 80+ member organizations (1,2). This allowed us to populate the three different CDTs described above with a multidisciplinary workforce that included nephrologists, interventional nephrologists, surgeons, radiologists, nurses, and industry representatives. In addition, the AVF, AVG, and catheter CDTs were able to share the output from their work with the KHI PFPC (the patient perspective is discussed below) as well as with FDA and CDC colleagues (the project output is discussed below). We felt that such a multidisciplinary approach would be more likely to achieve a comprehensive deliverable in this field compared with previous primarily clinical guideline–centered, single-stakeholder offerings in this area (6–8). We are also confident that the output from this project will build on an initial multidisciplinary effort in this area (9).

Project Output

An important issue that was quickly identified during the process of interactions both within and between the different CDTs and various organizations (industry, health professional and patient organizations, and federal agencies) involved in this project was the broad range of opinion in this area, such as on (1) the relative importance of physiologic maturation (flow and diameter) versus functional (suitability for dialysis) end points for AVF maturation and (2) the use of peripheral stick versus dialysis blood line cultures for the diagnosis of catheter-related bloodstream infections. Although we felt that this was a powerful signal that justified our focus on vascular access, we also felt that the appropriate way to present our deliberations would be to divide the operational output from this project into introductory, scientific, and regulatory modules, which include (1) an introductory piece (this manuscript), which includes the patient perspective and recommended common lexicon; (2) scientific output from the three CDTs (AVF, AVG, and catheters) that has been condensed into two manuscripts (3,4); and (3) an FDA commentary on the latter two manuscripts (5).

Scientific Output from the AVF, AVG, and Catheter CDTs

All three CDTs used a methodologic approach that included different combinations of a comprehensive literature review, a questionnaire, and expert opinion to develop the AVF, AVG, and catheter manuscripts. Important scientific aspects of these manuscripts include the following.

(1) The creation of a common lexicon of definitions to ensure that there was uniformity across the output of all three CDTs (Table 1 shows an abbreviated version, and Supplemental Material shows the full version).

(2) The grouping of end points into categories that reflect the goal of the intervention, drug, biologic, or device being tested. For example, the arteriovenous dialysis access manuscript has different end points for therapies that aim to enhance AVF maturation compared with therapies that target malfunction of a previously functioning AVF. The manuscript also has five different categories that link trial end points to the “life stages” of an arteriovenous access from creation to abandonment.

(3) The use of broad categories for clinical trial end points (as described above) in combination with both primary and secondary end points (providing both depth and versatility) that are relevant to both current and future therapies (including therapies on the basis of future novel biologic and engineering concepts). In addition, future priority areas for research are identified (especially in the catheter paper), with the goal of catalyzing efforts to address specific unmet clinical needs within the vascular access area.

Table 1.

Lexicon of definitions

| End point: end point is defined as a study outcome and how it is measured. End points can be primary, secondary, or exploratory; binary or continuous; and single or composite. All study end points should be determined a priori. |

| IDBD: the abbreviation IDBD refers to intervention, drug, biologic, or device. |

| Arteriovenous dialysis access circuit: the complete vascular circuit starting with the heart and including the complete feeding artery from its central origin, the arteriovenous dialysis access, and the complete venous drainage up to the superior vena cava-right atrial junction or the inferior vena cava-right atrial junction in the case of a lower extremity dialysis access. |

| Arteriovenous dialysis access patency: the status (yes/no) of an arteriovenous dialysis access with detectable blood flow through and beyond the anastomosis shown by either an imaging modality or physical examination (presence of a palpable thrill or audible bruit along some point of the arteriovenous dialysis access beyond the arteriovenous anastomosis). |

| Definitions of arteriovenous access patency durations: definitions of arteriovenous access patency durations are timeframes in which arteriovenous dialysis access is patent (defined above) and can be used for a variety of IDBD studies; thus, it may be necessary for patency to be defined from the time of initial arteriovenous dialysis access creation, the time of an index intervention, or both depending on the nature of the study (Figure 2). |

| Target lesion: a predefined area toward which the IDBD used in the trial was directed. This should be defined a priori in the study protocol. |

| Target zone: the area within the arteriovenous dialysis access circuit that encompasses the target lesion toward which the IDBD intervention is directed and the adjacent ± “X” portion of the access. This should be defined a priori in the study protocol. For example, target lesion ±2 cm. |

| Significant dialysis access stenosis: a reduction in the vessel luminal diameter (graft or draining venous system) that is ≥50% reduction in normal vessel diameter (see note below) accompanied by hemodynamic, functional, or clinical abnormalities not explained by reasons other than the dialysis vascular access lesion. In general, the hemodynamic, functional, or clinical abnormality should be present for two or more dialysis sessions. |

| Dialysis vascular access abandonment: the act of discontinuing the clinical use of a dialysis vascular access, because it is no longer functional and considered to not be salvageable. An abandoned dialysis access is one that can no longer be used for one- or two-needle prescribed dialysis, because it is unable to provide adequate blood flow and/or is deemed unsafe for the patient, and the associated problem cannot be corrected by any intervention: medical, endovascular, or surgical. |

| Intervention rate: the number of IDBD interventions performed (type to be specified in the protocol) on a dialysis vascular access within a defined time period. For example, the term “intervention rate, postintervention cumulative patency” would indicate the number of interventions performed during the postintervention period from index procedure to access abandonment. Additionally, the types of intervention and any complications incurred should be clearly indicated as per the study protocol. |

| Patency definitions |

| Patency from the time of dialysis access creation (figure 2 Upper panel): |

| Access primary patency: the time from arteriovenous dialysis access creation to the first of one of the following events: access thrombosis; any intervention designed to facilitate, maintain, or re-establish patency; the access reaches a censoring event as specified a priori in the study protocol; or study end. |

| Access assisted primary patency: term used to describe an access that needed assistance to maintain continued patency during the study period. It is calculated as the time from arteriovenous dialysis access creation to the first of one of the following events: access thrombosis, the access reaches a censoring event as specified a priori in the study protocol, or study end. This period includes all intervening interventions (surgical or endovascular) designed to maintain the functionality of the dialysis vascular access as long as patency is not lost. |

| Access cumulative patency: the time from arteriovenous dialysis access creation to access abandonment, when the access reaches a censoring event as specified a priori in the study protocol, or study end, including intervening manipulations (surgical or endovascular interventions) designed to maintain the functionality of the access. The term secondary patency has also been used in this context; however, this term has been misused in the literature, which makes it confusing. Hence, it is not used in this document. |

| Patency from the time of an index intervention: this may relate to the dialysis access circuit, the target zone, or both as defined a priori in the study protocol (figure 2 lower panel): |

| Postintervention primary patency: the time from the index IDBD to the first of one of the following events: access thrombosis; any intervention designed to facilitate, maintain, or re-establish patency; the access reaches a censoring event as specified a priori in the study protocol; or study end. |

| Postintervention assisted primary patency: term used to describe an access that needed assistance to maintain continued patency during the study period. It is calculated as the time from the index IDBD intervention to the first of one of the following events: access thrombosis, a surgical intervention that excludes the treated lesion from the dialysis access circuit, or the patient reaches a censored event as defined a priori in the study protocol. This period includes all intervening interventions (surgical or endovascular) designed to maintain the functionality of dialysis vascular access. |

| Postintervention cumulative patency: the time from the index IDBD intervention until the access is abandoned, including intervening manipulations (surgical or endovascular interventions) designed to maintain the functionality of a patent access, the patient reaches a censoring event as defined a priori in the study protocol, or study end. The term secondary patency has also been used in this context; however, this term has been misused in the literature, which makes it confusing. It is recommended that it not be used. |

These definitions (including the full version described in Supplemental Material) should be used in the development of clinical trial end points for vascular access in the context of any new therapeutic product. IDBD, intervention, drug, biologic, or device.

The FDA Commentary

The FDA commentary describes the different regulatory pathways for vascular access products and provides the FDA’s perspective on the output of the three CDTs, especially in areas where there was a relative lack of consensus.

Patient Perspective

An important focus of the KHI is to incorporate the patient perspective at every point within the product development process. To achieve this goal, we sought input from the PFPC (composed of up to ten members who are patients, family, care partners, and/or patient organization staff and office bearers) within the KHI, which has the goal of incorporating the patient voice and perspective into every KHI project. The insights and perspectives of the KHI PFPC on the arteriovenous access and catheter manuscripts are summarized below.

(1) Emphasized that this initiative was an important step forward in addressing what they described as the “Achilles heel” of hemodialysis, while noting that the patient perspective in this topic area was often very different from that of health care providers.

(2) Focused on the importance of ensuring that clinical trial end points in this area incorporate quality of life/patient satisfaction parameters.

(3) Highlighted the need to provide patients with lay summaries of ongoing and future clinical studies in vascular access to enhance study recruitment.

(4) Described the exponential effect of the patient voice on public initiatives within this area and other therapeutic areas.

In Summary

Our goal with this KHI project is to provide a durable framework for moving toward consensus in the broad area of clinical trial end points for dialysis vascular access. We recognize that this is a complex area due to its multidisciplinary nature and also, because of the high likelihood for the development of combination (drug/biologic plus device) products that target both vascular access creation and maintenance. Nevertheless, we strongly believe that the consensus building, multistakeholder, patient-centric approach that is championed in this series of manuscripts (1) establishes a solid foundation for clinical trial end points in this area (with the expectation for future revision as technology and science advance) and (2) will serve as a powerful catalyst to incentivize interest, innovation, and investment in this critically important but relatively neglected area of renal medicine.

Disclosures

S.S. receives research funding for Humacyte Inc. and serves on the Clinical Adjudication Committee, CR Bard. M.A. serves as a consultant for CorMedix. G.B. is an employee of Lifeline Vascular Access/DaVita. L.D. serves as a Data and Safety Monitoring Board Member of Proteon Therapeutics, Inc. M.G. has consultancy agreements with WL Gore TVA Merit Medical Proteon, ownership interest with TVA Medical, Hancock Jaffe Labs and receives honoraria from Cryolife, WL Gore, and Merit. T.L. serves as a consultant with Lifeline Vascular. C.L. receives research funding from TVA Medical, honoraria from Sanofi and InMed Pharmaceuticals. P.R.-C. serves on the Advisory Boards at Medtronic, CR Bard, WL Gore, TVA Medical and CorMedix. H.W. serves as a consultant for TVA Medical, Proteon Therapeutics, Inc., and CTI Clinical Trial Service, Inc. T.H., D.B.-M., and C.L. reported no disclosures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Kidney Health Initiative (KHI), a public-private partnership of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN), US Food and Drug Administration, and >75 member non-for-profit and for profit organizations. KHI funds were used to defray costs, including project management costs. There was no remuneration to KHI workgroup members. The authors are fully responsible for the content of this work. KHI makes every effort to avoid actual, potential, or perceived conflicts of interest among members of the workgroup. More information on the KHI, or conflict of interest policy, can be found at www.kidneyhealthinitiative.org. The views and opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views or policies of any KHI member organization, or the US Department of Health and Human Services. No mention of trade names, organizations, or reference to particular technologies implies endorsement by the KHI, or any US Government Agency.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Deceased.

See related articles, “Recommended Clinical Trial End Points for Dialysis Catheters,” “Definitions and End Points for Interventional Studies for Arteriovenous Dialysis Access,” and “FDA Regulatory Perspectives for Studies on Hemodialysis Vascular Access,” on pages 495–500, 501–512 and 513–518, respectively.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13321216/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Archdeacon P, Shaffer RN, Winkelmayer WC, Falk RJ, Roy-Chaudhury P: Fostering innovation, advancing patient safety: The kidney health initiative. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1609–1617, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linde PG, Archdeacon P, Breyer MD, Ibrahim T, Inrig JK, Kewalramani R, Lee CC, Neuland CY, Roy-Chaudhury P, Sloand JA, Meyer R, Smith KA, Snook J, West M, Falk RJ: Overcoming barriers in kidney health-forging a platform for innovation. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1902–1910, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beathard GA, Lok CE, Glickman MH, Al-Jaishi AA, Bednarski D, Cull DL, Lawson JH, Lee TC, Niyyar VD, Syracuse D, Trerotola SO, Roy-Chaudhury P, Shenoy S, Underwood M, Wasse M, Woo K, Yuo TH, Huber TS: Definitions and end points for interventional studies for arteriovenous dialysis access [published online ahead of print July 20, 2017]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol doi:10.2215/CJN.11531116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Allon M, Brouwer-Meir DJ, Abreo K, Baskin KM, Bregel K, Chand DH, Easom AM, Mermel L, Mokrzycki MH, Patel PR, Roy-Chaudhury P, Shenoy S, Valentini RP, Wasse H: Recommended clinical trial end points for dialysis catheters [published online ahead of print July 20, 2017]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol doi:10.2215/CJN.12011116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Hurst FP, Lee RE, Thompson AM, Pullin BD, Silverstein DM: FDA regulatory perspectives for studies on hemodialysis vascular access [published online ahead of print July 24, 2017]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol doi:10.2215/CJN.02900317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Sidawy AN, Spergel LM, Besarab A, Allon M, Jennings WC, Padberg FT Jr, Murad MH, Montori VM, O'Hare AM, Calligaro KD, Macsata RA, Lumsden AB; Society for Vascular Surgery: The society for vascular surgery: Clinical practice guidelines for the surgical placement and maintenance of arteriovenous hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg 48[5 Suppl]: 2S–25S, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray RJ, Sacks D, Martin LG, Trerotola SO; Society of Interventional Radiology Technology Assessment Committee: Reporting standards for percutaneous interventions in dialysis access. J Vasc Interv Radiol 14: S433–S442, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Kidney Foundation: III. NKF-K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for vascular access: Update 2000. Am J Kidney Dis 37[Suppl 1]: S137–S181, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee T, Mokrzycki M, Moist L, Maya I, Vazquez M, Lok CE; North American Vascular Access Consortium: Standardized definitions for hemodialysis vascular access. Semin Dial 24: 515–524, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.