Abstract

Background Renal osteodystrophy is common in advanced CKD, but characterization of bone turnover status can only be achieved by histomorphometric analysis of bone biopsy specimens (gold standard test). We tested whether bone biomarkers and high-resolution peripheral computed tomography (HR-pQCT) parameters can predict bone turnover status determined by histomorphometry.

Methods We obtained fasting blood samples from 69 patients with CKD stages 4–5, including patients on dialysis, and 68 controls for biomarker analysis (intact parathyroid hormone [iPTH], procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide [PINP], bone alkaline phosphatase [bALP], collagen type 1 crosslinked C-telopeptide [CTX], and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b [TRAP5b]) and scanned the distal radius and tibia of participants by HR-pQCT. We used histomorphometry to evaluate bone biopsy specimens from 43 patients with CKD.

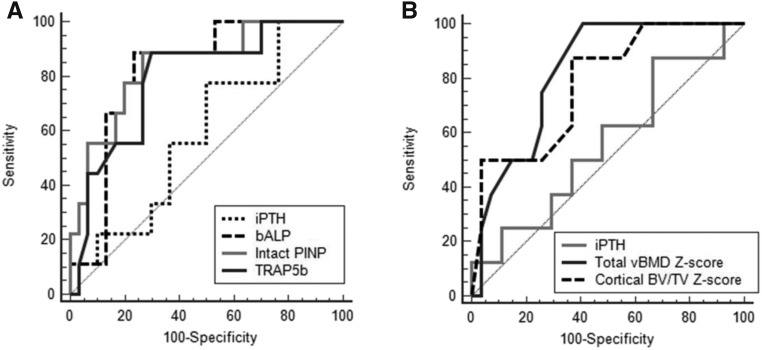

Results Levels of all biomarkers tested were significantly higher in CKD samples than control samples. For discriminating low bone turnover, bALP, intact PINP, and TRAP5b had an areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUCs) of 0.82, 0.79, and 0.80, respectively, each significantly better than the iPTH AUC of 0.61. Furthermore, radius HR-pQCT total volumetric bone mineral density and cortical bone volume had AUCs of 0.81 and 0.80, respectively. For discriminating high bone turnover, iPTH had an AUC of 0.76, similar to that of all other biomarkers tested.

Conclusions The biomarkers bALP, intact PINP, and TRAP5b and radius HR-pQCT parameters can discriminate low from nonlow bone turnover. Despite poor diagnostic accuracy for low bone turnover, iPTH can discriminate high bone turnover with accuracy similar to that of the other biomarkers, including CTX.

Keywords: renal osteodystrophy, mineral metabolism, parathyroid hormone, hyperparathyroidism, chronic kidney disease, chronic renal failure

Renal osteodystrophy is characterized by abnormal bone turnover, mineralization, and volume, which can only be assessed on bone histomorphometry (gold standard test).1 However, bone biopsy is invasive and rarely performed due to patients’ reluctance or limited expertise in the procedure and bone histomorphometry. Hence, current clinical practice still relies on intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), although it has been shown to have low sensitivity and specificity to assess bone turnover.2–4 The poor diagnostic accuracy of iPTH limits its use to guide therapies that target bone mineral density (BMD) or bone turnover.

Very high levels of both bone alkaline phosphatase (bALP) and iPTH are strongly predictive of high bone turnover in CKD.4–10 However, bALP has better predictive ability than iPTH for low bone turnover.4–6,9 There are other bone turnover biomarkers that are directly released during the process of bone resorption (e.g., collagen type 1 crosslinked C-telopeptide [CTX] and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b [TRAP5b]) and bone formation (e.g., procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide [PINP]); thus, they are potentially more accurate in assessing bone turnover in CKD.

The changes in BMD and microarchitecture associated with high or low bone turnover cannot be adequately assessed by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which is a two-dimensional imaging technique.11 However, high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) can detect microarchitectural changes in both the cortical and the trabecular bone compartments. Previous studies using HR-pQCT showed that patients with CKD had thinner cortical bone and lower trabecular bone volume compared with healthy controls.12–14

The emergence of bone biomarkers and HR-pQCT offers the possibility of replacing bone biopsy, but their diagnostic accuracy for predicting bone turnover in advanced CKD is unknown. We aimed to simultaneously test if biomarkers and HR-pQCT can identify patients with advanced CKD and low or high bone turnover as shown on histomorphometry. We also tested whether these noninvasive tests have better diagnostic accuracy than iPTH.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a cross-sectional study of patients with CKD stages 4–5 (including those on dialysis) ages 30–80 years old. The exclusion criteria included fracture/orthopedic surgery in the preceding 6 months; started/changed the dose of phosphate binders, vitamin D, or calcimimetics within 4 weeks of study entry; and received antiresorptive anabolic agent or systemic glucocorticoid in the preceding 6 months. All patients attending our nephrology center who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were invited to take part in the study. We also recruited age- and sex-matched controls with eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. The exclusion criteria were similar to those in CKD group, and we also excluded participants with known osteoporosis. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the South Yorkshire Research Ethics Committee. All participants gave written informed consent. All samples and imaging studies were obtained purely for research and summarized below. Complete methods are provided in Supplemental Material.

Bone Biomarkers

Fasting morning blood samples were taken, stored at −80°C, and analyzed at the end of the study. For patients on hemodialysis, blood samples were taken on the day after their hemodialysis session. We measured serum iPTH, bALP, intact PINP, CTX, TRAP5b, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D using the IDS-iSYS autoanalyzer (Immunodiagnostic Systems). Total PINP was measured using the Cobas e411 automated immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics). We measured fasting serum calcium, phosphate, total alkaline phosphatase, and creatinine on a Roche Cobas c701/702 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics) on the same day as sample collection. eGFR was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.

Bone Imaging

HR-pQCT of the distal radius and tibia was performed with XtremeCT (Scanco Medical AG) using a standard protocol. The images were analyzed with standard software (version 6.0; Scanco Medical AG) for volumetric BMD (milligrams per centimeter3) and microarchitectural parameters. The extended cortical measurement was also performed.

DXA of the lumbar spine (L1–L4), hip, and forearm was performed using the Hologic Discovery A densitometer (Hologic Inc.). Mean areal BMD (grams per centimeter2) was calculated using Hologic APEX software (version 3.4.2).

Transiliac Bone Biopsy and Histomorphometry

Bone biopsy was only performed in patients with CKD using tetracycline bone labeling. A transiliac bone biopsy was performed under local anesthetic using an 8-gauge Jamshidi 4-mm trephine and needle. The samples were analyzed using the Bioquant Osteo histomorphometry system (Bioquant Image Analysis Corporation), which uses standardized nomenclature.15 The samples fulfilled the histomorphometry minimum acceptable total section area in the standard analysis region of 30 mm2.16 All histomorphometry analyses were performed by a single operator (O.G.), and normal bone turnover was defined as bone formation rate/bone surface (BFR/BS) of 18–38 μm3/μm2 per year.17

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean (SD) and median (interquartile range [IQR]). We used t tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, and chi-squared tests to compare the characteristics of patients with CKD and controls, and we used Spearman rank analysis to identify the associations between variables.

We selected 43 controls who were age and sex matched to the 43 patients with CKD with bone histomorphometry to obtain HR-pQCT Z scores. HR-pQCT Z scores were used to control for the age and sex effects on bone microarchitecture and BMD. The Z scores were calculated using the formula: (HR-pQCT CKD measurement − mean of control group)/(SD of control group). DXA BMD Z scores were obtained from the Hologic software.

For receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, patients with CKD were grouped into low/nonlow and high/nonhigh bone turnover categories on the basis of bone turnover on histomorphometry (BFR/BS). The proportions of low and high bone turnover in this study were used as prevalence of the disease. We classified area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.6–0.7 as poor, 0.7–0.8 as fair, 0.8–0.9 as good, and 0.9–1.0 as excellent diagnostic accuracy. Combining variables for ROC analysis was performed using regression analysis.

We used P<0.05 to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 and MedCalc v16.8.4.

Results

Participants and the Bone Turnover on Histomorphometry

The demographics of 69 patients with advanced CKD stages 4–5 (including those on dialysis) and 68 age- and sex-matched control participants are shown in Table 1. There were 44 patients with CKD not yet on dialysis with median (IQR) eGFR of 13 (11–16) ml/min per 1.73 m2 and 25 patients on dialysis (hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis). Median (IQR) eGFR for controls was 81 (72 to >90) ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Table 1.

Demographics, biomarkers, and imaging parameters in patients with CKD and control participants

| Variables | CKD, n=69 | Control, n=68 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 62 (12) | 62 (12) | |

| Men, N | 53 | 53 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27 (4.1) | 28 (4.3) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes, % | 28 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Previous fragility fracture, % | 22 | 7 | <0.05 |

| Biomarkers | |||

| iPTH, pg/ml | 188 (121–280) | 32 (27–45) | <0.001 |

| Intact PINP, ng/ml | 67.5 (42.8–107.7) | 38.5 (31.8–55.3) | <0.001 |

| Total PINP, ng/ml | 125 (72.8–237.2) | 41.4 (33.7–56.7) | <0.001 |

| bALP, μg/L | 22.3 (16.6–33.3) | 17 (12.9–20.2) | <0.001 |

| tALP, IU/L | 88 (73–126) | 65.5 (55.3–78) | <0.001 |

| CTX, ng/ml | 1.49 (0.76–2.39) | 0.27 (0.19–0.5) | <0.001 |

| TRAP5b, U/L | 4.9 (3.2–6.9) | 3.8 (3.3–4.5) | 0.001 |

| Adjusted calcium, mmol/L | 2.28 (0.15) | 2.28 (0.07) | 0.90 |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 1.53 (0.3) | 1.06 (0.15) | <0.001 |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, ng/ml | 22.9 (9.4) | 23.9 (7.0) | 0.50 |

| HR-pQCT distal radius | |||

| Total vBMD, mg/cm3 | 266.2 (75.56) | 308.47 (74.2) | 0.003 |

| Cortical vBMD, mg/cm3 | 782.58 (110.66) | 821.04 (88.7) | 0.040 |

| Trabecular vBMD, mg/cm3 | 156.69 (46.17) | 184.6 (41.42) | 0.001 |

| Cortical thickness, mm | 0.61 (0.27) | 0.71 (0.26) | 0.06 |

| Cortical porosity, % | 3.0 (2.3–4.2) | 3.2 (2.0–3.8) | 0.40 |

| Cortical BV/TV, % | 90.0 (85.4–92.1) | 90.7 (88.6–93.4) | 0.10 |

| Trabecular thickness, mm | 0.064 (0.012) | 0.073 (0.013) | <0.001 |

| Trabecular number, 1/mm | 2.01 (0.363) | 2.11 (0.296) | 0.14 |

| Trabecular separation, mm | 0.434 (0.371–0.496) | 0.4 (0.349–0.443) | 0.06 |

| Trabecular BV/TV, % | 13.1 (3.8) | 15.4 (3.5) | 0.001 |

| HR-pQCT distal tibia | |||

| Total vBMD, mg/cm3 | 276.99 (63.67) | 314.97 (61.2) | 0.001 |

| Cortical vBMD, mg/cm3 | 819.85 (88.67) | 858.7 (67.89) | <0.01 |

| Trabecular vBMD, mg/cm3 | 172.12 (41.06) | 189.99 (41.12) | 0.01 |

| Cortical thickness, mm | 1.05 (0.36) | 1.25 (0.35) | 0.001 |

| Cortical porosity, % | 7.1 (5.7–10.4) | 6.8 (4.7–10.3) | 0.20 |

| Cortical BV/TV, % | 86.2 (6.0) | 88.1 (4.9) | 0.05 |

| Trabecular thickness, mm | 0.075 (0.014) | 0.081 (0.013) | 0.01 |

| Trabecular number, 1/mm | 1.92 (0.35) | 1.97 (0.4) | 0.40 |

| Trabecular separation, mm | 0.444 (0.395–0.522) | 0.425 (0.359–0.523) | 0.20 |

| Trabecular BV/TV, % | 14.3 (3.4) | 15.8 (3.4) | 0.01 |

| DXA BMD Z score | |||

| Forearm | −0.4 (1.5) | 0.2 (1.4) | 0.02 |

| Total hip | −0.2 (1.0) | 0.6 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Lumbar spine | 0.4 (1.7) | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.70 |

Data are presented as mean (SD) for normal distribution variables and median (interquartile range) for non-normal distribution variables. Group differences were tested using independent t tests for normal distribution variables, Mann–Whitney U tests for non-normal distribution variables, and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. BMI, body mass index; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; PINP, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide; bALP, bone alkaline phosphatase; tALP, total alkaline phosphatase CTX, collagen type 1 crosslinked C-telopeptide; TRAP5b, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; vBMD, volumetric bone mineral density; BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume; DXA, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry; BMD, bone mineral density.

In total, 49 bone biopsies were performed, but only 43 samples were adequate for histomorphometry analysis. Among these 43 patients, 28 (65%) had CKD but were not yet on dialysis, mean (SD) age was 59 (12) years old, 77% were men, 26% had diabetes, and 26% had previous fragility fracture. Their current medications are shown in Table 2, but none were taking calcimimetics. On the basis of BFR/BS on histomorphometry, 26% of patients had low bone turnover, 34% had normal bone turnover, and 40% had high bone turnover (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biomarkers and imaging parameters for low, normal, and high bone turnover categories in patients with advanced CKD (n=43)

| Variables | Low, n=11 | Normal, n=15 | High, n=17 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFR/BS, μm3/μm2 per 1 d | 13.8 (3.6–15.5) | 27.5 (22.5–32.2) | 67.4 (46.5–112.5) | <0.001 |

| Medications, % | ||||

| Vitamin D | 45 | 13 | 47 | |

| Calcium-based phosphate binder | 9 | 20 | 41 | |

| Noncalcium-based phosphate binder | 0 | 7 | 6 | |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| iPTH, pg/ml | 172 (119–292) | 172 (86–194) | 347 (161–381) | <0.05 |

| Intact PINP, ng/ml | 44.1 (29.2–68.4) | 81.1 (54.3–92.4) | 107.9 (63.5–182) | <0.01 |

| Total PINP, ng/ml | 76.3 (51.7–159.3) | 127.3 (68.4–221.7) | 214 (110.6–403) | <0.05 |

| bALP, μg/L | 17.7 (5.6) | 25.9 (8.7) | 34.4 (13.3) | <0.01 |

| tALP, IU/L | 82 (53–86) | 94 (82–127) | 115 (82–156) | <0.05 |

| CTX, ng/ml | 1.01 (0.68) | 1.46 (0.67) | 2.65 (1.68) | <0.01 |

| TRAP5b, U/L | 3.2 (2.9–4.3) | 5.2 (3.2–7.4) | 5.8 (4.8–8.5) | <0.05 |

| Adjusted calcium, mmol/L | 2.27 (2.22–2.33) | 2.32 (2.26–2.35) | 2.24 (2.14–2.40) | 0.60 |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 1.48 (1.30–1.77) | 1.61 (1.43–1.83) | 1.30 (1.25–1.55) | 0.10 |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, ng/ml | 23 (9.9) | 23.7 (8.2) | 22.6 (10.3) | 0.95 |

| HR-pQCT radius Z score | ||||

| Total vBMD | −0.11 (0.63) | −1.06 (0.66) | −0.97 (1.08) | <0.05 |

| Cortical vBMD | 0.49 (−0.47 to 0.9) | −0.63 (−1.4 to −0.14) | −0.84 (−1.67 to 0.15) | 0.09 |

| Trabecular vBMD | −0.31 (0.83) | −1.03 (0.57) | −1.11 (1.31) | 0.16 |

| Cortical thickness | 0.07 (0.8) | −0.76 (0.82) | −0.64 (0.98) | 0.10 |

| Cortical porosity | −0.51 (−0.95 to −0.02) | −0.12 (−0.94 to 1.58) | 0.10 (−0.47 to 0.90) | 0.15 |

| Cortical BV/TV | 0.72 (−0.08 to 0.97) | −0.2 (−1.48 to 0.27) | −0.23 (−1.46 to 0.27) | <0.05 |

| Trabecular thickness | −0.43 (−0.82 to −0.18) | −1.14 (−1.57 to −0.79) | −1.21 (−1.77 to 0.11) | 0.07 |

| Trabecular number | −0.03 (1.01) | −0.11 (0.84) | −0.66 (1.58) | 0.39 |

| Trabecular separation | −0.13 (−0.5 to 0.71) | 0.30 (−0.39 to 0.55) | 0.59 (−0.50 to 1.18) | 0.50 |

| Trabecular BV/TV | −0.30 (0.82) | −1.01 (0.57) | −1.09 (1.31) | 0.17 |

| HR-pQCT tibia Z score | ||||

| Total vBMD | −0.34 (0.91) | −1.05 (0.90) | −0.92 (1.13) | 0.21 |

| Cortical vBMD | 0.26 (−0.93 to 0.44) | −0.60 (−2.0 to 0.31) | −0.21 (−2.0 to 0.13) | 0.13 |

| Trabecular vBMD | −0.48 (0.92) | −0.63 (0.88) | −0.70 (1.11) | 0.86 |

| Cortical thickness | −0.18 (0.92) | −1.1 (0.86) | −0.86 (1.16) | 0.10 |

| Cortical porosity | −0.31 (0.52) | 0.43 (1.26) | 0.31 (1.17) | 0.23 |

| Cortical BV/TV | 0.36 (−0.15 to 0.73) | −0.43 (−1.82 to 0.70) | 0.14 (−2.12 to 0.37) | 0.17 |

| Trabecular thickness | −0.70 (−0.87 to 0.23) | −0.93 (−1.62 to 0.21) | −0.78 (−1.66 to 0.14) | 0.44 |

| Trabecular number | −0.31 (1.23) | −0.03 (0.76) | −0.07 (0.92) | 0.74 |

| Trabecular separation | 0.56 (−0.75 to 0.84) | −0.09 (−0.30 to 0.55) | −0.04 (−0.44 to 0.52) | 0.66 |

| Trabecular BV/TV | −0.46 (0.91) | −0.60 (0.88) | −0.67 (1.10) | 0.86 |

| DXA BMD Z score | ||||

| Forearm | −0.24 (0.88) | −0.31 (0.99) | −0.94 (1.33) | 0.18 |

| Total hip | −0.07 (0.76) | −0.35 (0.96) | −0.38 (1.05) | 0.68 |

| Lumbar spine | −0.10 (−0.5 to 0.6) | 0.2 (−0.8 to 1.0) | 0 (−0.8 to 1.3) | 0.86 |

Data are presented as mean (SD) for normal distribution variables or median (interquartile range) for non-normal distribution variables. Group differences were tested using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests depending on the distribution of the variables. BFR/BS, bone formation rate/bone surface; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; PINP, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide; bALP, bone alkaline phosphatase; tALP, total alkaline phosphatase; CTX, collagen type 1 crosslinked C-telopeptide; TRAP5b, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; vBMD, volumetric bone mineral density; BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume; DXA, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry; BMD, bone mineral density.

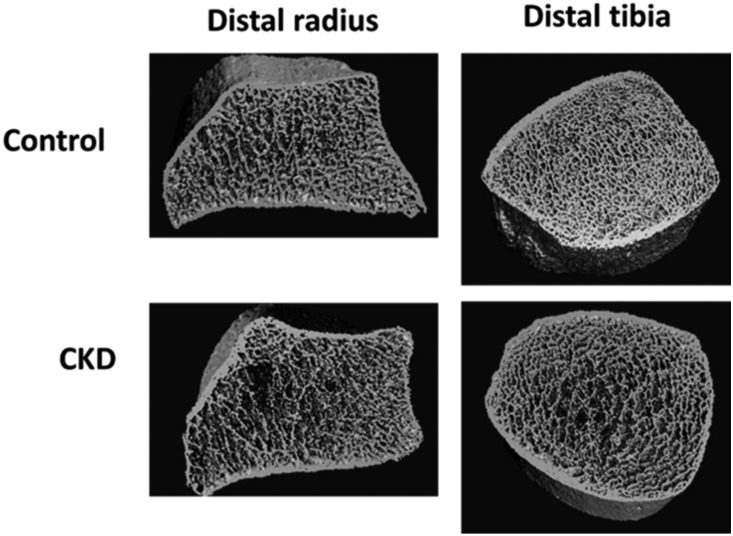

Biomarkers and Imaging in CKD and Controls

Patients with CKD had significantly higher biomarker levels compared with controls (Table 1). On HR-pQCT, patients with CKD had lower volumetric BMD, lower trabecular thickness, and lower trabecular bone volume at the distal radius and distal tibia compared with controls (Table 1). Additionally, patients with CKD had a thinner cortical bone at the tibia. Figure 1 shows examples of three-dimensional reconstruction of HR-pQCT images at both sites in this study.

Figure 1.

A CKD patient had trabecular bone impairment, whereas the control participant had normal trabecular bone microarchitecture. These are examples of high-resolution peripheral computed tomography (HR-pQCT) three-dimensional images of distal radius and distal tibia in this study.

Areal BMD Z scores by DXA at the forearm and total hip were also lower in patients with CKD compared with controls (Table 1); 59% of the CKD group had osteopenia (T score, −1.0 to −2.5) and 25% had osteoporosis (T score <−2.5) as assessed by BMD at the three sites. In the control group, 51% had osteopenia, and 12% had osteoporosis.

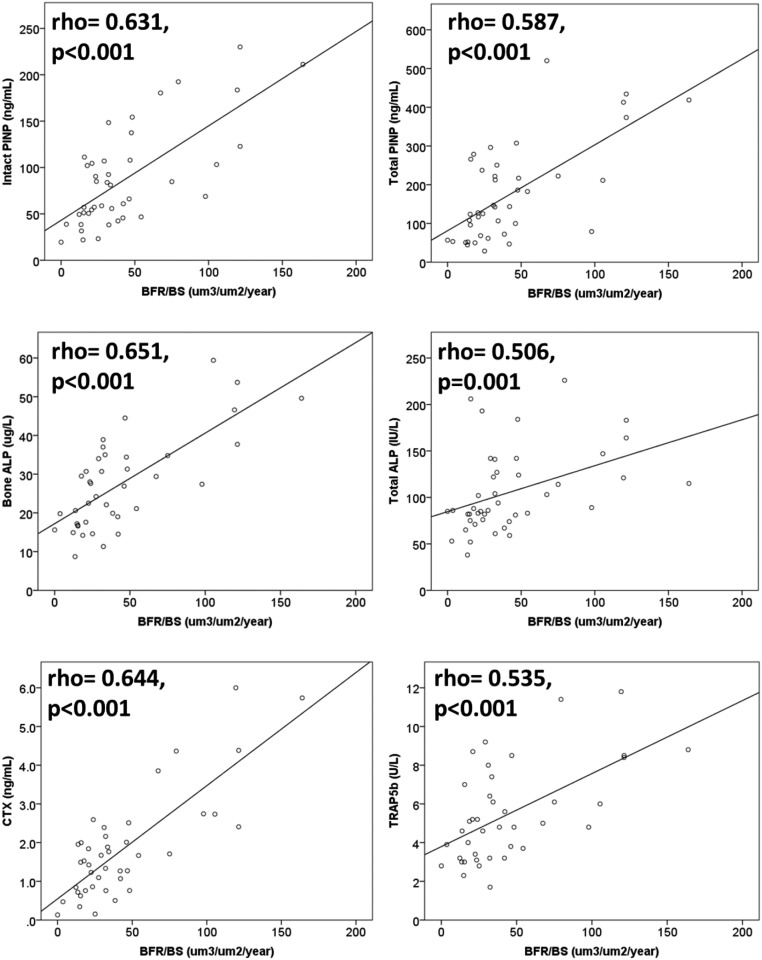

Relationship between Bone Turnover on Histomorphometry and Biomarkers and Imaging in CKD

In 43 patients with CKD and bone histomorphometry data, all biomarkers were significantly correlated with each other (Supplemental Table 1). iPTH was positively associated with bone turnover (BFR/BS; rho=0.42; P<0.01), but the other biomarkers showed higher correlations with bone turnover (Figure 2). There were significant differences for all of the biomarkers between low, normal, and high bone turnover categories (Table 2).

Figure 2.

All biomarkers showed positive correlations with bone turnover on histomorphometry (n=43). ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BFR/BS, bone formation rate/bone surface; CTX, collagen type 1 crosslinked C-telopeptide; PINP, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide; TRAP5b, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b.

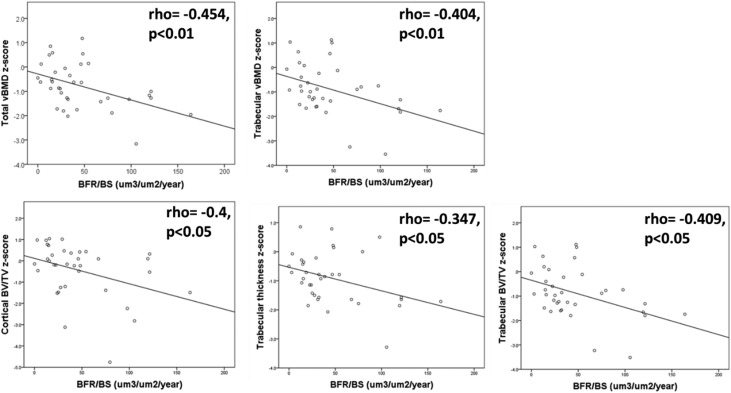

Bone turnover on histomorphometry was negatively associated with radius Z scores for BMD and microarchitecture (Figure 3), but no significant associations were found with tibia HR-pQCT Z scores. Differences were only significant for radius HR-pQCT total BMD and cortical bone volume (P<0.05) between the three bone turnover categories (Table 2). On DXA, only the forearm BMD Z score was significantly associated with bone turnover (rho=−0.307; P<0.05). No significant differences were found for DXA BMD Z scores between the bone turnover categories (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Distal radius high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) parameters showed negative correlations with bone turnover on histomorphometry (n=43). BFR/BS, bone formation rate/bone surface; BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume; vBMD, volumetric bone mineral density.

Diagnostic Accuracy of Biomarkers and Imaging for Low Bone Turnover

In ROC analysis for discriminating low from nonlow bone turnover, AUC for bALP was 0.824, AUC for intact PINP was 0.794, and AUC for TRAP5b was 0.799 (Table 3). These AUCs were significantly better (P<0.05) than the AUC for iPTH, which was 0.606 (Figure 4A). Combining biomarkers did not improve the AUC.

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers and radius high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography for identifying patients with low bone turnover

| Variables | AUC (95% CI) | Criterion | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV, % | NPV, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers | ||||||

| iPTH | 0.563 (0.40 to 0.72) | ≤183 pg/ml | 70 | 53 | 32 | 85 |

| Intact PINP | 0.794 (0.64 to 0.90) | ≤57 ng/ml | 80 | 75 | 50 | 92 |

| Total PINP | 0.719 (0.56 to 0.85) | ≤124 ng/ml | 80 | 68 | 44 | 91 |

| bALP | 0.824 (0.67 to 0.93) | ≤21 μg/L | 89 | 77 | 53 | 96 |

| tALP | 0.753 (0.60 to 0.87) | ≤88 IU/L | 91 | 63 | 46 | 95 |

| CTX | 0.766 (0.61 to 0.88) | ≤0.84 ng/ml | 60 | 84 | 55 | 87 |

| TRAP5b | 0.799 (0.64 to 0.91) | ≤4.6 U/L | 89 | 71 | 47 | 96 |

| Radius HR-pQCT Z score | ||||||

| Total vBMD | 0.811 (0.65 to 0.92) | >−1.0 | 100 | 59 | 45 | 100 |

| Cortical BV/TV | 0.802 (0.64 to 0.92) | >−0.2 | 89 | 63 | 44 | 94 |

| Combined variables | ||||||

| bALP and radius total vBMD Z score | 0.797 (0.62 to 0.92) | Not available | 100 | 58 | 39 | 100 |

AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; PINP, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide; bALP, bone alkaline phosphatase; tALP, total alkaline phosphatase; CTX, collagen type 1 crosslinked C-telopeptide; TRAP5b, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; vBMD, volumetric bone mineral density; BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume.

Figure 4.

Biomarkers and distal radius high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) parameters can discriminate patients with CKD and low bone turnover. (A) Receiver operating characteristic curves show that the biomarkers bone alkaline phosphatase (bALP), intact procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (PINP), and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRAP5b) performed significantly better than intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) in discriminating patients with low bone turnover. (B) Distal radius HR-pQCT parameters were not significantly better than iPTH, despite areas under the curve being >0.80. BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume; vBMD, volumetric bone mineral density.

Radius HR-pQCT Z scores for total BMD and cortical bone volume had AUCs of 0.811 and 0.802, respectively, for discriminating low bone turnover (Figure 4B, Table 3). However, these AUCs were not significantly better than the iPTH AUC. Tibia HR-pQCT Z scores only had an AUC≤0.70. All three sites’ DXA BMD Z scores also had nonsignificant AUCs (Supplemental Table 2). Combining bALP and radius total BMD Z scores did not improve the AUC (Table 3).

Diagnostic Accuracy of Biomarkers and Imaging for High Bone Turnover

In ROC analysis for discriminating high from nonhigh bone turnover, iPTH had an AUC of 0.76, which was similar to the AUCs for the other biomarkers (Table 4). Combining biomarkers did not improve the AUC. All bone imaging parameters also had nonsignificant AUCs (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers for identifying patients with high bone turnover

| Biomarkers | AUC (95% CI) | Criterion | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV, % | NPV, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPTH | 0.760 (0.60 to 0.88) | >327 pg/ml | 53 | 96 | 90 | 75 |

| Intact PINP | 0.765 (0.61 to 0.88) | >107 ng/ml | 53 | 92 | 82 | 74 |

| Total PINP | 0.725 (0.56 to 0.85) | >142 ng/ml | 75 | 68 | 60 | 81 |

| bALP | 0.750 (0.59 to 0.87) | >31 μg/L | 56 | 83 | 69 | 74 |

| tALP | 0.670 (0.51 to 0.81) | >102 IU/L | 65 | 73 | 61 | 76 |

| CTX | 0.762 (0.61 to 0.88) | >2.39 ng/ml | 53 | 96 | 90 | 75 |

| TRAP5b | 0.710 (0.55 to 0.84) | >4.6 U/L | 81 | 58 | 57 | 82 |

AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; PINP, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide; bALP, bone alkaline phosphatase; tALP, total alkaline phosphatase; CTX, collagen type 1 crosslinked C-telopeptide; TRAP5b, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b.

Discussion

This is the first study to simultaneously compare biomarkers and HR-pQCT with bone histomorphometry to determine their diagnostic accuracy in discriminating bone turnover status in patients with advanced CKD. bALP and radius HR-pQCT can discriminate low bone turnover, and their AUCs are >0.80. We also found that iPTH, all of the biomarkers, and bone imaging had similarly suboptimal diagnostic accuracy for discriminating high bone turnover.

bALP, intact PINP, and TRAP5b can discriminate patients with low bone turnover better than iPTH, most likely because they do not accumulate in advanced CKD.18,19 Secondary hyperparathyroidism is a common complication in advanced CKD, and it has a major role in CKD mineral bone disorder.1 iPTH is a poor diagnostic test to discriminate low bone turnover in patients with advanced CKD, partly due to the assay used. A second generation iPTH assay measures the whole (1–84) PTH molecule and the (7–84) PTH fragment. The fragment accumulates in CKD and has an antagonistic effect on bone turnover.20 Despite those limitations, iPTH can still discriminate high bone turnover with similar accuracy as other biomarkers used in this study. iPTH has 90% positive predictive value (PPV) for high bone turnover, which is consistent with that in previous studies.6,7,10 The optimal cutoff value for discriminating high bone turnover in this study is five times the upper limit of normal, whereas Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes CKD mineral bone disorder guidelines recommend that the iPTH level is maintained two to nine times the upper limit of normal in patients on dialysis.1 The number of patients on dialysis in our study was too small for further analysis to make a comparison.

In this study, bALP had an AUC>0.80 and better diagnostic accuracy for low bone turnover than iPTH, findings that are consistent with previous studies.5,6,8,9 bALP and other biomarkers in this study had consistently low PPV but high negative predictive value for the optimal threshold (criterion) for low bone turnover. We also found that bALP only has 69% PPV for discriminating high bone turnover, whereas previous studies found >90% PPV.6,7,10

Sprague et al.4 recently published the diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers in predicting bone turnover in 492 patients on dialysis from four countries. They also showed that iPTH had similar diagnostic accuracy to bALP and PINP in predicting high bone turnover. They found that bALP and iPTH had the highest diagnostic accuracy for low bone turnover, but we found iPTH to be a poor diagnostic test for low bone turnover. They also found that combining iPTH and bALP improved the discrimination of both low and high bone turnover, but this is not the case in our study. There are differences between the study and our study. We included patients not yet on dialysis and patients on dialysis, which may account for the different proportion of patients with low bone turnover. Although our sample size was smaller, the proportion of patients with low bone turnover was similar to that in other studies.5,9 In contrast, Sprague et al.4 reported that around 60% of patients had low bone turnover, but most of their biopsies were performed for clinical indication, whereas our biopsies were collected purely for research. Our histomorphometry analysis was performed by a single operator to reduce intraobserver variability, whereas Sprague et al.4 had bone histomorphometry analyzed in several centers with different ranges of bone turnover defined as normal. The assays used for iPTH and bALP were also different from ours, and Sprague et al.4 used total PINP, whereas we evaluated total PINP and intact PINP separately.

PINP is cleaved off from type 1 collagen during the bone formation process. Total PINP assay measures the trimeric propeptide and its monomeric fragments, whereas the intact PINP assay only measures the trimeric propeptide.19 The trimeric propeptide is cleared from circulation by liver endothelial cells,21 whereas the monomeric fragments are cleared by the kidneys; hence, the fragments accumulate in advanced CKD.19 We have shown that, in advanced CKD, (1) only intact PINP can discriminate low bone turnover better than iPTH and that (2) both have suboptimal diagnostic accuracy for high bone turnover. Although total PINP is often used in the field of osteoporosis, we do not recommend its use to assess bone turnover in advanced CKD.

Biomarker profiles in patients on dialysis may differ from those in patients with CKD not yet on dialysis, even those with similar bone turnover status, because biomarkers, such as CTX, may be dialyzed.22 Hence, our patients on hemodialysis had blood samples taken the day after a dialysis session, but we did not assess residual renal function. These issues may have introduced bias in our study. However, the number of patients not yet on dialysis was small, with fewer than ten patients each in the low and high bone turnover categories, which makes further analysis in this subgroup questionable.

Patients with CKD in our study had lower BMD on HR-pQCT compared with controls, which is mostly due to trabecular bone impairment. Additionally, patients with CKD also had thinner cortical bone at the tibia. Previous studies also found that patients with CKD had lower BMD on HR-pQCT compared with controls due to both trabecular and cortical bone impairment.12–14 However, we did not match the BMDs of our control participants with the BMDs of patients with CKD, and we excluded participants with known osteoporosis, which may have introduced bias.

We found that radius BMD and microarchitecture were negatively associated with bone turnover in advanced CKD. Negri et al.14 showed a similar trend on HR-pQCT in women on dialysis, but they used biomarkers as measures of bone turnover rather than bone histomorphometry. We also found that patients with CKD and normal and high bone turnover had significantly lower radius BMD compared with those with low bone turnover, mostly due to lower cortical bone volume. Gerakis et al.23 described similar findings using DXA in patients on hemodialysis who had a bone biopsy. We did not find any difference in DXA BMDs between bone turnover categories. Importantly, DXA is unable to discriminate bone turnover status in advanced CKD.

Distal radius HR-pQCT can discriminate low bone turnover from nonlow bone turnover in patients in this study. However, it is important to recognize that the effects of bone turnover on microarchitecture are dynamic, whereas HR-pQCT is a static test. Thus, the cross-sectional use of HR-pQCT is perhaps more appropriate in assessing bone volume (static measurement) rather than bone turnover (dynamic measurement).24 Nevertheless, the use of bone imaging could be complementary to biomarkers in discriminating bone turnover status and deciding treatment decisions (for example, in osteoporotic CKD).

We included patients with CKD not yet on dialysis and patients with CKD on dialysis, and we assessed bone turnover using the gold standard bone biopsy; however, there were several limitations to our study. This was a single-center observational study with a small number of participants. However, the proportions of patients with low/high bone turnover were similar to those of previous studies, and we had a broad range of bone turnover, which is important in assessing diagnostic test accuracy. We were unable to assess patients not yet on dialysis and patients on dialysis separately. Hence, our results must be interpreted in the context of CKD stages 4–5 and dialysis.

In conclusion, bALP, intact PINP, TRAP5b, and radius HR-pQCT were able to discriminate low bone turnover in patients with advanced CKD. Despite poor diagnostic accuracy for low bone turnover, iPTH can discriminate high bone turnover with similar accuracy to other biomarkers in this study. In clinical practice, iPTH and bALP remain the diagnostic tests of choice to discriminate high and low bone turnover. However, we believe that all four biomarkers and radius HR-pQCT can potentially be used for patient selection in clinical trials in advanced CKD as we continue to search for bone-specific treatment to reduce fracture risk in this population.

Disclosures

S.S. has received research grants and support from Immunodiagnostics Systems and Biomedica. R.E. has received grants and consulting fees from Immunodiagnostics Systems and Roche Diagnostics. O.G., F.G., M.P., and A.K. have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sister Angela Green (lead research nurse), Selina Bratherton (bone imaging and project management), Louese Dunn (renal research coordinator), Prof. Mark Wilkinson (bone biopsy training), Dr. David Hughes (bone histology support), and all of the study participants. The study was conducted at the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Facility at the Northern General Hospital, Sheffield.

This study was funded by Kidney Research UK, Immunodiagnostic Systems, and Sheffield Hospitals Charity. S.S. is a Kidney Research UK Clinical Research Fellow.

Abstracts relating to this manuscript were presented at the European Calcified Tissue Society Conference, Salzburg, Austria, May 13–16, 2017 and the United Kingdom Kidney Week Conference, Liverpool, United Kingdom, June 19–21, 2017.

All of the authors worked independently from the funders. The funders were not involved in the study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; writing of this manuscript; or the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related article, “The Quest for Better Biomarkers of Bone Turnover in CKD,” on pages 1353–1355.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017050584/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl 113: S1–S130, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herberth J, Monier-Faugere MC, Mawad HW, Branscum AJ, Herberth Z, Wang G, et al.: The five most commonly used intact parathyroid hormone assays are useful for screening but not for diagnosing bone turnover abnormalities in CKD-5 patients. Clin Nephrol 72: 5–14, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barreto FC, Barreto DV, Moysés RM, Neves KR, Canziani ME, Draibe SA, et al.: K/DOQI-recommended intact PTH levels do not prevent low-turnover bone disease in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 73: 771–777, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sprague SM, Bellorin-Font E, Jorgetti V, Carvalho AB, Malluche HH, Ferreira A, et al.: Diagnostic accuracy of bone turnover markers and bone histology in patients with CKD treated by dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 559–566, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couttenye MM, D’Haese PC, Van Hoof VO, Lemoniatou E, Goodman W, Verpooten GA, et al.: Low serum levels of alkaline phosphatase of bone origin: A good marker of adynamic bone disease in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 1065–1072, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ureña P, Hruby M, Ferreira A, Ang KS, de Vernejoul MC: Plasma total versus bone alkaline phosphatase as markers of bone turnover in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 506–512, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher S, Jones RG, Rayner HC, Harnden P, Hordon LD, Aaron JE, et al.: Assessment of renal osteodystrophy in dialysis patients: Use of bone alkaline phosphatase, bone mineral density and parathyroid ultrasound in comparison with bone histology. Nephron 75: 412–419, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coen G, Ballanti P, Bonucci E, Calabria S, Centorrino M, Fassino V, et al.: Bone markers in the diagnosis of low turnover osteodystrophy in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 2294–2302, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bervoets AR, Spasovski GB, Behets GJ, Dams G, Polenakovic MH, Zafirovska K, et al.: Useful biochemical markers for diagnosing renal osteodystrophy in predialysis end-stage renal failure patients. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 997–1007, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehmann G, Ott U, Kaemmerer D, Schuetze J, Wolf G: Bone histomorphometry and biochemical markers of bone turnover in patients with chronic kidney disease Stages 3 - 5. Clin Nephrol 70: 296–305, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nickolas TL, Stein EM, Dworakowski E, Nishiyama KK, Komandah-Kosseh M, Zhang CA, et al. : Rapid cortical bone loss in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res 28: 1811–1820, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacchetta J, Boutroy S, Vilayphiou N, Juillard L, Guebre-Egziabher F, Rognant N, et al. : Early impairment of trabecular microarchitecture assessed with HR-pQCT in patients with stage II-IV chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res 25: 849–857, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cejka D, Patsch JM, Weber M, Diarra D, Riegersperger M, Kikic Z, et al.: Bone microarchitecture in hemodialysis patients assessed by HR-pQCT. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2264–2271, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Negri AL, Del Valle EE, Zanchetta MB, Nobaru M, Silveira F, Puddu M, et al.: Evaluation of bone microarchitecture by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) in hemodialysis patients. Osteoporos Int 23: 2543–2550, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, et al. : Bone histomorphometry: Standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 2: 595–610, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Recker RR, Kimmel DB, Dempster D, Weinstein RS, Wronski TJ, Burr DB: Issues in modern bone histomorphometry. Bone 49: 955–964, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malluche HH, Mawad HW, Monier-Faugere MC: Renal osteodystrophy in the first decade of the new millennium: Analysis of 630 bone biopsies in black and white patients. J Bone Miner Res 26: 1368–1376, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada S, Inaba M, Kurajoh M, Shidara K, Imanishi Y, Ishimura E, et al.: Utility of serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRACP5b) as a bone resorption marker in patients with chronic kidney disease: Independence from renal dysfunction. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 69: 189–196, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koivula MK, Ruotsalainen V, Björkman M, Nurmenniemi S, Ikäheimo R, Savolainen K, et al.: Difference between total and intact assays for N-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen reflects degradation of pN-collagen rather than denaturation of intact propeptide. Ann Clin Biochem 47: 67–71, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slatopolsky E, Finch J, Clay P, Martin D, Sicard G, Singer G, et al.: A novel mechanism for skeletal resistance in uremia. Kidney Int 58: 753–761, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melkko J, Hellevik T, Risteli L, Risteli J, Smedsrød B: Clearance of NH2-terminal propeptides of types I and III procollagen is a physiological function of the scavenger receptor in liver endothelial cells. J Exp Med 179: 405–412, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez L, Torregrosa JV, Peris P, Monegal A, Bedini JL, Martinez De Osaba MJ, et al.: Effect of hemodialysis and renal failure on serum biochemical markers of bone turnover. J Bone Miner Metab 22: 254–259, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerakis A, Hadjidakis D, Kokkinakis E, Apostolou T, Raptis S, Billis A: Correlation of bone mineral density with the histological findings of renal osteodystrophy in patients on hemodialysis. J Nephrol 13: 437–443, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marques ID, Araújo MJ, Graciolli FG, Reis LM, Pereira RM, Custódio MR, et al.: Biopsy vs. peripheral computed tomography to assess bone disease in CKD patients on dialysis: Differences and similarities. Osteoporos Int 28: 1675–1683, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.