Abstract

Objective

Dimensional personality trait models have gained favor as an alternative to categorical personality disorder (PD) diagnosis; however, debate persists regarding whether these traits should be conceptualized as maladaptive at both extremes (i.e., maladaptively bipolar) or just one trait pole (i.e., unipolar)

Method

To inform the debate on maladaptive bipolarity, linear and nonlinear relations between personality traits and dysfunction were examined in a large psychiatric patient sample (N = 365). Participants self-reported on normal-range and pathological personality domains, life satisfaction, specific interpersonal problems, and broad psychosocial functioning. In addition, participants were interviewed regarding specific psychiatric symptoms and broad psychosocial functioning.

Results

All traits related moderately to strongly with at least one dysfunction variable. All traits were predominately correlated with dysfunction at one pole; however, several small linear relations provided some evidence for maladaptively high extraversion and agreeableness. None of the significant nonlinear effects provided clear evidence for maladaptivity at both ends of any trait.

Conclusion

Taken together, these results suggest that broad personality traits are predominately maladaptive at one extreme; however, in limited cases, the opposite extreme may also be maladaptive.

Keywords: Five Factor Model, Personality Disorder, Bipolarity, Maladaptive, Personality Traits

The official Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, 5th edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) personality disorder (PD) classification system has been widely criticized (Clark, 2007; Krueger, et al., 2011; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009), with noted problems ranging from excessive diagnostic overlap (Zimmerman, Rothschild, & Chelminski, 2005) to limited descriptive coverage (e.g., Verheul, Bartak, & Widiger; 2007). Researchers have responded to these limitations by recommending that the current system be replaced by a trait model (e.g., Clark, 2007; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009). Despite support for such a change, disagreements persist regarding the nature of the traits that should be included (Simms et al., 2011; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009). Some researchers advocate including maladaptively bipolar dimensions, with pathology manifesting at both ends (Samuel, 2011; Widiger & Presnall, 2013), whereas others question the empirical basis for this position (Krueger et al., 2011; Wright & Simms, 2014). The present study adds to the literature on this topic by empirically examining the maladaptive bipolarity of two prominent PD trait models.

Defining Trait Polarity and Maladaptivity

Important, though rarely discussed, issues in the maladaptive bipolarity debate include defining polarity and maladaptivity. One simple definition of polarity might focus on a trait dimension’s observed indicators. A dimension may be bipolar if it has indicators (items, scales, etc.) that correlate both positively and negatively with the dimension (e.g., Goldberg, 1990), or unipolar if indicators correlate with the dimension in one direction only. An alternative, theoretically richer definition might instead focus on whether both ends of a dimension can be defined and empirically located within a nomological network (e.g., Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). From this perspective, a trait dimension’s external relations are an important test of its polarity. Notably, these definitions focus on whether meaningful constructs occupy both ends of a trait dimension, which is separate from whether these constructs are maladaptive.

Maladaptive personality traits can be seen as characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that either directly (e.g., distress) or indirectly (e.g., disorganization; Mullins-Sweatt & Widiger, 2010; Ro & Clark, 2009, 2013) lead to negative outcomes. Thus, maladaptively bipolar traits have well-defined opposing trait poles that both relate to negative outcomes. Two broad questions relevant to the PD literature are (a) whether opposing trait poles (e.g., agreeableness vs. antagonism) are ever both maladaptive and (b) how maladaptively bipolar dimensions should be represented. The second question is complex, but may be informed by questions about trait extremity (e.g., does one trait pole become problematic at an extreme few reach?), dysfunction severity (e.g., are trait poles associated with equally consequential problems?), dysfunction pervasiveness (e.g., do poles vary in the diversity or range of negative outcomes they relate to?), and variability at maladaptive trait poles (e.g., are there notable individual differences in affective, behavioral, or cognitive patterns at a trait pole?). The answers to these questions have important practical consequences. For instance, the latter two questions can inform whether additional conceptual and measurement resolution is needed to describe individual differences at maladaptive trait poles, such as through narrower traits (e.g., facets). With some exceptions (e.g., Samuel, 2011; Carter et al., 2016), these questions are rarely stated or researched, although answers to them are implied by specific PD trait models and measures.

Personality Measures and Models

Fundamental to evaluating claims regarding the maladaptive bipolarity of PD traits is the recognition that recently proposed PD models (e.g., Krueger et al., 2012; Simms et al., 2011; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2011) were developed in part through the refinement of the measures that operationalize them (e.g., Loevinger, 1957). Thus, in evaluating the maladaptive bipolarity of traits within a model, it is important to consider how these trait models are assessed.

The development and progression of the NEO family of personality measures (e.g., McCrae, Costa, & Martin, 2005) is central to the Five Factor Model (FFM) of PD (FFM-PD; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009). These measures assess 30 ostensibly bipolar (though not necessarily maladaptively bipolar) personality facets that are organized within five broad domains. NEO measures have been widely used and validated, especially in research settings (e.g., Ozer & Benet-Martinez, 2006); maintaining a connection with this basic research is a fundamental FFM-PD goal (e.g., Samuel, 2011). FFM-PD researchers view FFM domains as maladaptively bipolar (Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009) and there is evidence (e.g., Coker, Samuel, & Widiger, 2002) items reflecting maladaptive characteristics exist at all poles, though they are unevenly distributed (i.e., more maladaptive items at one pole). This unevenness has been viewed by FFM-PD researchers as a measurement limitation (e.g., Haigler & Widiger, 2001); however, given that this unevenness is similar to the distribution of socially undesirable adjectives in the English language (e.g., Coker et al., 2002), it might be argued that FFM traits are simply not as maladaptive at opposing poles. Regardless, some FFM-PD researchers have constructed measures that attempt to assess an equal number of maladaptive features at all trait poles (e.g., Rojas & Widiger, 2014).

Recently developed PD trait models have been strongly influenced by the Personality Psychopathology Five (PSY-5; Harkness & McNulty, 1994), in that they aimed to ensure adequate coverage of PSY-5 domains (i.e., negative emotionality, introversion, aggressiveness, disconstraint, and psychoticism), which resemble pathological variants of the FFM (e.g., Wright & Simms, 2014). Notably, these models began with a focus on articulating and measuring unipolar facets (i.e., meaningfully defined at one pole), then empirically tested their higher-order structure. Although the PSY-5 domains originally were operationalized as supplementary scales for the MMPI-2 (Harkness & McNulty, 1994), recent faceted measures with conceptual links to the PSY-5 include the Personality Inventory for the DSM-5 (PID-5; Krueger et al., 2012) and the Computerized Adaptive Test of Personality Disorder (CAT-PD; Simms et al., 2011). Factor analyses of these facet scales indicate PSY-5 structure (Krueger et al., 2012; Wright & Simms, 2014), with factors that are defined by meaningful and opposed constructs (e.g., antagonism vs. agreeableness); however, the factor loadings from such studies tend to indicate maladaptive unipolarity, with the exception of rigid perfectionism loading opposite disinhibition facets.

Taken together, prominent PD trait measures are characterized by different implicit (and explicit) assumptions regarding the maladaptive bipolarity of their dimensions. A distinction can be made between (a) conceptual arguments for maladaptively bipolar traits and (b) evidence that such conceptual models are valid. Much of the literature has focused on the former; in the present study, we aim to contribute explicitly to the latter.

Evidence for Maladaptive Unipolarity vs. Bipolarity

Evidence for maladaptive bipolarity in relations to psychopathology is mixed. For instance, correlations between common mental disorders (e.g., former Axis I; APA, 2000) and NEO domains (Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010), as well as PID-5 traits (Hopwood et al., 2013), indicate that traits relate to disorders at one end. However, meta-analyses of DSM PD relations to NEO domains and facets (Samuel & Widiger, 2008) show a moderate (i.e., r = .33) correlation between Histrionic PD (HPD) and extraversion, as well as a small association (i.e., r = .24) between conscientiousness and Obsessive-Compulsive PD (OCPD). Clinician ratings of prototypic PD cases additionally indicate the potential maladaptivity of specific openness and agreeableness facets (Samuel & Widiger, 2004). In contrast, PID-5 trait relations to DSM PDs are unidirectional for each trait domain (Fowler et al., 2015).

A limitation of trait-symptom research is that the DSM may not exhaustively represent psychopathology related to personality pathology (e.g., Verheul et al., 2007). Nonetheless, personality pathology of all forms would be expected to interrupt one or more aspects of psychosocial functioning (e.g., Ro & Clark, 2009). Recent work (Ro & Clark, 2013; Calabrese & Simms, 2014) has found that normal-range and maladaptive traits relate to well-being (e.g., self-actualization), interpersonal functioning, and basic functioning (e.g., self-care) in a manner consistent with maladaptive unipolarity. In contrast, Mullins-Sweatt and Widiger (2010) reported some evidence for the maladaptivity of extraversion and agreeableness when examining the relations between NEO traits and a range of impairment measures. Specifically, extraversion related negatively to most impairment scales, but positively to the Couple’s Critical Incidents Checklist (CCIC) interpersonal problems and reliability problems scales. Similarly, agreeableness only related positively to two scales: the CCIC cooperativeness problems scale and the Cooperative/Over-Conventional scale derived from the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (e.g., Horowitz et al., 1988). Notably, Mullins-Sweatt and Widiger (2010) replicated previous findings from the validation of the CCIC, which itself was designed to reflect problems “linked to motivational dynamics of the five-factor model” (Kosek, 1998); however, the primary focus of this measure is on “dissatisfaction an individual is experiencing with his or her spouse,” not necessarily the individual’s problems (Mullins-Sweatt & Widiger, 2010). Finally, a longitudinal study has demonstrated that highly conscientious individuals experience greater decreases in well-being following prolonged unemployment (Boyce, Wood, & Brown, 2010).

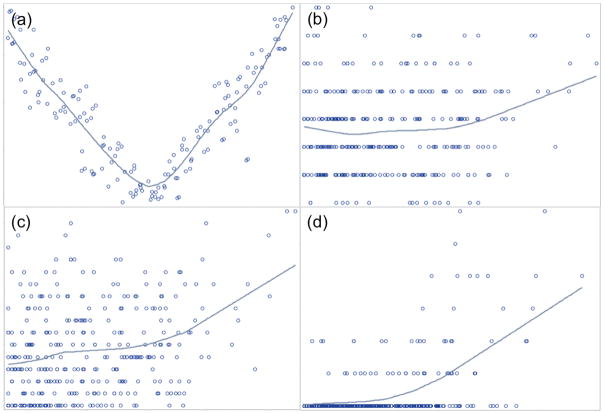

An additional limitation of this literature has been its focus on linear relations between traits and impairment. Insofar as opposing trait extremes are likely to reflect impairment, curvilinear (i.e., U-shaped; see Figure 1a) relations between traits and general impairment may be expected (Samuel, 2011). PD trait research rarely investigates such nonlinear effects; however, a more extensive literature on the topic exists in industrial-organizational research (e.g., Carter et al., 2013). In particular, there is evidence of curvilinear relations between neuroticism and work environment contributions, conscientiousness and task performance (Le et al., 2010), as well as extraversion and sales (Grant, 2013). Several recent studies also have examined curvilinear relations between personality and clinically relevant outcomes. For instance, Daspe, Sabourin, Péloquin, Lussier, and Wright (2013) found a small curvilinear effect for the relationship between neuroticism and dyadic adjustment. Wright, Hopwood, and Simms (2015) found a curvilinear effect for affiliative interpersonal problems (e.g., too cold vs. too warm) as related to interpersonal behavior instability. Finally, Carter, Guan, Maples, Williamson, and Miller (2016) found a curvilinear effect between conscientiousness and well-being, though the decrement in well-being at high levels of conscientiousness was minor relative to the lack of well-being associated with low conscientiousness.

Figure 1.

The Present Study

Little empirical work has focused specifically on the maladaptive polarity of traits within PD models and the broader literature that can inform this topic has produced inconsistent results and conclusions. Additionally, the primary focus on linear effects is problematic, as tests of nonlinear effects provide another compelling test of maladaptive polarity. In the present study, we examine whether personality traits are maladaptively bipolar and whether trait poles vary in the breadth (e.g., pervasiveness) of negative outcomes they relate to, through analyzing trait-impairment relations in a large psychiatric patient sample. In doing so, we evaluate whether traits exhibit (a) linear relations of opposing direction with specific forms of impairment (e.g., symptom patterns), and/or (b) nonlinear relations with more general impairment (e.g., life satisfaction). Given that the majority of evidence for trait bipolarity comes from research with a single measure (i.e., CCIC; Mullins-Sweatt & Widiger, 2010) and that other empirical work suggests that traits have generally linear relations with psychopathology (e.g., Kotov et al., 2010), we predict that strong evidence for maladaptive bipolarity will not be found, and when it is, trait poles will differ in the number and diversity of negative outcomes to which they relate. As little research examines nonlinear relations between traits and clinically-relevant variables, we analyze curvilinear relations on an exploratory basis to inform future theory and research.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Current and recent psychiatric patients (N = 6281 ), recruited from Western New York mental health clinics, attended a four-hour session during which they completed structured interviews and computer-administered self-report measures. Participants were compensated with $50 and transportation reimbursement. Most of these participants were in treatment (80%) or had been within the last one (10%) to two (5%) years. The present study used a subset of these participants (N = 336) who completed measures of normal and maladaptive personality traits as well as multiple measures of psychosocial impairment. The average age of this subset was 40.2 (SD = 12.7), and most participants were female (68%). Participants identified mostly as Caucasian (72%) and African American (25%). Fewer than 3% of participants identified as Hispanic, Asian, or American Indian or Alaskan Native. Relative to excluded participants (i.e., N = 292), included participants were more likely to be Caucasian (72% of included vs. 52% of excluded; χ2[1, N = 627] = 28.79, p < .001), female (68% vs. 59%; χ2[1, N = 627] = 5.57, p = .02), and were on average 6 years younger (t[626] = 6.59, p < .001).

Personality Measures

NEO Personality Inventory-3 First Half (NEO PI-3FH)

The NEO-PI-3 (McCrae et al., 2005) is a revision of the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) intended to improve readability and reliability. Research identified 37 replacement items, which improved the measure’s psychometric properties without altering its structure (McCrae et al., 2005). The full measure consists of 240 statements that are rated on a five-point scale (i.e., strongly disagree to strongly agree). These items form 30 facet scales, with six facets for each of the higher-order domains (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness). The NEO-PI-3FH consists of the first 120 items of the NEO-PI-3, with four items for each of the 30 facets. Despite being half the length of the original measure, relations to full-length scales are strong (Mdn r = .91) and the overall structure of the measure is preserved (McCrae & Costa, 2007). In the present sample, the median domain-level alpha coefficient was .82 (range = .80–.90).

Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5)

The PID-5 (Krueger et al., 2012) is a 220-item questionnaire with 25 scales, one for each DSM-5 Section III pathological personality facet. These facet scales are organized into five domains (Negative Affectivity, Antagonism, Detachment, Disinhibition, and Psychoticism) that are conceptually and empirically similar to the PSY-5 (Anderson et al., 2013; Harkness & McNulty, 1994). Each facet scale is measured by 4 to 14 items measured on a four-point scale of 0 (very false or often false) to 3 (very true or often true). In this study, the median PID-5 domain alpha coefficient was .93 (Range = .93–.95).

Interview Functioning and Psychopathology Measures

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)

The MINI 5.0.0 was developed as a brief structured diagnostic interview, covering commonly assessed and diagnosed disorders (Sheehan et al., 1998). Interview questions correspond directly to DSM symptoms. Previous research suggests that the MINI is both reliable and valid, converging well with other well-validated measures (Sheehan et al., 1998). In the present study, the MINI 5.0.0 was adapted, with permission, to assess currently experienced symptoms of DSM-5 (APA, 2013) disorders. In addition, skip-out rules were relaxed to allow for more comprehensive symptom assessment. Dimensional symptom counts were scored for each disorder and internal consistency, when calculable, was adequate (Mdn α = .81, range = .59–.91; See Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for All Measures

| Measure | Scale | α | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | ||||||

| NEO-PI-3FH | Neuroticism | .90 | 74.87 | 17.65 | 25.00 | 118.00 |

| Extraversion | .82 | 75.01 | 14.71 | 38.00 | 110.00 | |

| Openness | .82 | 84.13 | 12.92 | 43.00 | 116.00 | |

| Agreeableness | .89 | 85.43 | 13.06 | 43.00 | 119.00 | |

| Conscientiousness | .80 | 78.50 | 15.85 | 32.00 | 114.00 | |

| PID-5 | Negative Affect | .95 | 1.37 | 0.70 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| Detachment | .93 | 1.06 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 2.91 | |

| Psychoticism | .95 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 2.61 | |

| Antagonism | .93 | 0.97 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 2.49 | |

| Disinhibition | .93 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 3.00 | |

| Psychopathology & Functioning | ||||||

| General Impairment | ||||||

| SWLS Total | .90 | 16.74 | 7.93 | 5.00 | 35.00 | |

| MDA Total | .72 | 454.06 | 229.21 | 0.00 | 1000.00 | |

| WHODAS Total | .86 | 27.39 | 20.02 | 0.00 | 84.21 | |

| IIP-SC | Domineering | .74 | 2.92 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 12.00 |

| Vindictive | .76 | 3.13 | 3.17 | 0.00 | 16.00 | |

| Coldness | .83 | 4.53 | 3.71 | 0.00 | 16.00 | |

| Socially Avoidant | .90 | 5.65 | 4.78 | 0.00 | 16.00 | |

| Nonassertive | .87 | 6.43 | 4.34 | 0.00 | 16.00 | |

| Exploitable | .76 | 5.84 | 3.76 | 0.00 | 16.00 | |

| Overly Nurturant | .78 | 7.25 | 3.91 | 0.00 | 16.00 | |

| Intrusive | .77 | 4.56 | 3.67 | 0.00 | 14.00 | |

| Total | .93 | 40.30 | 21.24 | 0.00 | 116.00 | |

| MINI 6 | Major Depression | .83 | 3.79 | 2.80 | 0.00 | 9.00 |

| Mania | .70 | 3.02 | 2.88 | 0.00 | 8.00 | |

| Dysthymia | .87 | 3.96 | 2.58 | 0.00 | 7.00 | |

| Panic Disorder | .74 | 6.55 | 6.07 | 0.00 | 17.00 | |

| Social Anxiety | N/A1 | 1.18 | 1.69 | 0.00 | 4.00 | |

| Obsessive Compulsive | N/A1 | 0.49 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 3.00 | |

| Post-Traumatic Stress | .91 | 6.75 | 5.65 | 0.00 | 20.00 | |

| Generalized Anxiety | .79 | 4.66 | 2.48 | 0.00 | 8.00 | |

| Alcohol Use | .89 | 1.38 | 2.69 | 0.00 | 11.00 | |

| (Other) Substance Use | .91 | 1.36 | 2.96 | 0.00 | 11.00 | |

| Current Psychosis | .66 | 0.35 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 6.00 | |

| Lifetime Psychosis | .59 | 0.75 | 1.44 | 0.00 | 8.00 | |

| Schizophrenia | N/A1 | 0.32 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 3.00 | |

| Suicidality | N/A1 | 3.69 | 5.42 | 0.00 | 31.00 | |

| SCID-II | Avoidant PD | .71 | 3.29 | 2.05 | 0.00 | 7.00 |

| Dependent PD | .52 | 2.11 | 1.63 | 0.00 | 8.00 | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive PD | .47 | 3.98 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 8.00 | |

| Paranoid PD | .76 | 3.52 | 2.22 | 0.00 | 7.00 | |

| Schizoid PD | .47 | 2.64 | 1.55 | 0.00 | 7.00 | |

| Schizotypal PD | .58 | 3.46 | 1.85 | 0.00 | 8.00 | |

| Histrionic PD | .57 | 1.71 | 1.65 | 0.00 | 6.00 | |

| Narcissistic PD | .70 | 3.95 | 2.35 | 0.00 | 9.00 | |

| Borderline PD | .80 | 5.00 | 2.73 | 0.00 | 9.00 | |

| Antisocial PD | .53 | 0.87 | 1.68 | 0.00 | 7.00 | |

Note. N = 336 for all measures.

= Not calculable due to skip rules in the interview.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-II)

The SCID-II is a structured interview used for the diagnosis of DSM-IV PDs (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995). The SCID-II includes a Personality Questionnaire (SCID-II PQ) that functions as a screening measure for the interview (e.g., Ryder, Costa, & Bagby, 2007). Participants completed the SCID-II PQ first and were then interviewed, focusing only on the criteria of PDs they screened positive for (i.e., met criteria for diagnosis based on SCID-II PQ). Criteria not reviewed during the interviews were recorded as indicated by the SCID-II PQ. Dimensional criterion counts were created for each disorder, for each individual. The internal consistency of these scores varied by disorder (Mdn α = .58, Range = .47–.80; see Table 1).

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) 12-item Version, Interview-Administered

The WHODAS 2.0 12-item interview is a measure of functioning and disability in six domains: cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities (e.g., work), and participation in society (Üstün et al., 2010). Interviewers presented participants with a five-point rating scale (“None” to “Extreme or cannot do”) and instructed them to “answer these questions thinking about how much difficulty you have had, on average, over the past 30 days, while doing the activity as you usually do it.” The full self-report WHODAS 2.0 has been extensively validated and the interview version used has been found to explain 81% of the variance in the full measure (e.g., Üstün et al., 2010). In the present study, the two items comprising each domain were summed to create domain-level scores. The median domain alpha was .62 (range = .51–.88); the alpha for the WHODAS 2.0 total score was .86.

All interviews were conducted by clinical psychology doctoral students and study staff who were trained extensively. Weekly supervision sessions were conducted by the second author (L.J.S.) and consisted of discussing cases and comparing interviewing practices via video, making interviewing technique adjustments as needed. A randomly selected subset of 120 interviews were reviewed by a second interviewer to establish inter-rater reliability, which was high for MINI and SCID-II assessed disorders (Mdn κ = 0.96, range = 0.66–1.00) and WHODAS functioning scales (Mdn intraclass correlation = .98, range = .94–1.00).

Self-Report Functioning Measures

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) is 5-item scale that assesses participants’ global self-evaluation of their life (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”). Items are rated on scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) and summed such that higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction. In the present study, the alpha coefficient of the SWLS was .90.

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Short Circumplex (IIP-SC)

The IIP-SC (Soldz et al., 1995) is a 32-item measure of interpersonal behaviors that individuals perform excessively (e.g., “I argue with other people too much”) or deficiently (e.g., “It is hard for me to feel close to other people”). Items form 8 four-item scales (Domineering, Vindictive, Cold, Socially Avoidant, Nonassertive, Exploitable, Overly Nurturant, and Intrusive) that adhere to circumplex structure (Soldz et al., 1995). In addition, interpersonal distress severity is often assessed (e.g., Williams & Simms, 2016) through summing all items. In the present study, IIP-SC octant scales (α Range = .74–.90) and severity estimate (α. = 93) showed adequate internal consistency.

Multidimensional Dysfunction Aggregate (MDA)

Participants were presented with five questions related to psychosocial functioning (e.g., “In the past 6 months, to what extent have you noticed LIMITATIONS in your ability to control your impulsive behavior, to be self-directed, or to be a responsible and effective person?”) and responded using a visual analog scale ranging 0 (“not at all”) to 1000 (“very much”). Four of these questions were designed to assess the four psychosocial impairment domains found by Ro and Clark (2009): well-being (e.g., subjective well-being), basic functioning (e.g., self-care), self-mastery (e.g., internal self-control), and interpersonal and social relationships (e.g., disagreeableness). An additional question assessing difficulties at work and school also was included. These items were examined both separately and as a dysfunction composite, which was adequately reliable (α = .72)

Analyses and Results

Descriptive statistics and the alpha coefficients for all variables are provided in Table 1. Analyses proceeded in two steps: (a) examining bivariate correlations to examine whether personality traits demonstrate both positive and negative associations with a variety of psychosocial impairment variables, and (b) conducting polynomial regressions to examine whether curvilinear relationships exist between traits and impairment indicators, with U-shaped trait-impairment relationships (see Figure 1a) providing evidence for bipolarity (i.e., individuals at extremes demonstrate impairment, but those at moderate levels do not). For regression analyses, residual distributions, skedasticity, and outliers were examined to ensure that regression assumptions (e.g., Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003) were not violated. In the cases where they were violated, variable transformations (e.g., logarithmic) and outlier deletion were used to examine the effect on parameter estimates.

Bivariate Correlations

Bivariate correlations between traits and all impairment indicators are provided in Table 2. For each trait, 90% or more of significant correlations were in one direction; thus, to aide interpretation, significant (p < .01) correlations that go against the major directional trend for a trait are underlined. There were four such correlations, and all occurred with NEO-PI-3FH traits. First, extraversion yielded a small positive (i.e., r = .28) relationship with HPD, which contrasted with otherwise large negative correlations with impairment. Second, agreeableness demonstrated small positive correlations with three IIP-SC scales related to warm-submissive interpersonal problems, with the “Overly Nurturant” problems scale showing the strongest correlation (r = .21). All significant (p < .05) PID-5 domain correlations with functioning and psychopathology were unidirectional, indicative of unipolarity.

Table 2.

Trait Relations to Impairment and Psychopathology

| NEO-PI-3

|

PID-5

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | O | A | C | NA | DET | PSY | ANT | DIS | |

| General Impairment | ||||||||||

| (−)SWLS | .57 | −.42 | −.08 | −.05 | −.39 | .47 | .41 | .16 | −.09 | .34 |

| MDA Total | .56 | −.30 | −.05 | −.18 | −.43 | .56 | .50 | .40 | .16 | .50 |

| WHODAS Total | .44 | −.34 | −.16 | −.07 | −.35 | .47 | .54 | .39 | .09 | .45 |

| IIP-SC | ||||||||||

| Domineering | .40 | −.12 | −.23 | −.54 | −.28 | .46 | .34 | .47 | .50 | .51 |

| Vindictive | .41 | −.32 | −.30 | −.56 | −.25 | .50 | .51 | .47 | .48 | .51 |

| Coldness | .35 | −.52 | −.25 | −.26 | −.26 | .37 | .75 | .43 | .29 | .43 |

| Socially Avoidant | .47 | −.72 | −.20 | −.08 | −.31 | .44 | .68 | .34 | .05 | .38 |

| Nonassertive | .40 | −.47 | −.06 | .16 | −.37 | .39 | .41 | .21 | .06 | .34 |

| Exploitable | .39 | −.35 | −.06 | .16 | −.33 | .45 | .37 | .27 | .06 | .38 |

| Overly Nurturant | .37 | −.24 | .01 | .21 | −.26 | .45 | .26 | .27 | .01 | .33 |

| Intrusive | .37 | .01 | .02 | −.18 | −.38 | .44 | .11 | .39 | .32 | .44 |

| Total | .57 | −.52 | −.18 | −.15 | −.44 | .62 | .62 | .49 | .28 | .58 |

| MINI-6 | ||||||||||

| Major Depression | .54 | −.36 | −.12 | −.19 | −.39 | .54 | .50 | .42 | .13 | .48 |

| Mania | .33 | −.15 | −.17 | −.29 | −.22 | .38 | .32 | .42 | .27 | .44 |

| Dysthymia | .47 | −.36 | −.18 | −.16 | −.32 | .45 | .51 | .35 | .10 | .40 |

| Panic Disorder | .34 | −.18 | .05 | −.09 | −.12 | .35 | .27 | .32 | .09 | .23 |

| Social Anxiety | .43 | −.36 | −.01 | −.15 | −.26 | .49 | .35 | .39 | .14 | .38 |

| Obsessive Compulsive | .33 | −.17 | −.01 | −.15 | −.15 | .34 | .23 | .38 | .21 | .33 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress | .50 | −.31 | −.09 | −.22 | −.36 | .57 | .50 | .48 | .22 | .52 |

| Generalized Anxiety | .49 | −.19 | −.02 | −.16 | −.22 | .51 | .29 | .28 | .13 | .36 |

| Alcohol Use | .06 | .04 | .01 | −.15 | −.11 | .13 | .07 | .20 | .21 | .21 |

| (Other) Substance Use | .09 | .05 | −.03 | −.20 | −.15 | .13 | .02 | .10 | .16 | .21 |

| Current Psychosis | .12 | −.05 | .02 | −.19 | −.06 | .21 | .18 | .49 | .27 | .23 |

| Lifetime Psychosis | .06 | −.09 | .01 | −.14 | −.06 | .13 | .18 | .42 | .16 | .18 |

| Schizophrenia | .19 | −.12 | .01 | −.20 | −.11 | .26 | .22 | .45 | .25 | .27 |

| Suicidality | .34 | −.17 | .04 | −.06 | −.18 | .34 | .30 | .33 | .06 | .23 |

| SCID-II | ||||||||||

| Paranoid | .48 | −.31 | −.20 | −.48 | −.25 | .53 | .48 | .46 | .34 | .45 |

| Schizoid | .10 | −.46 | −.35 | −.14 | −.14 | .16 | .60 | .25 | .13 | .21 |

| Schizotypal | .39 | −.25 | .01 | −.25 | −.26 | .47 | .36 | .56 | .24 | .41 |

| Antisocial | .15 | .03 | −.07 | −.35 | −.15 | .20 | .18 | .33 | .38 | .32 |

| Borderline | .65 | −.28 | −.10 | −.36 | −.46 | .67 | .49 | .54 | .30 | .64 |

| Histrionic | .12 | .28 | .14 | −.27 | −.14 | .24 | −.08 | .28 | .40 | .26 |

| Narcissistic | .28 | .00 | −.09 | −.54 | −.17 | .41 | .26 | .44 | .52 | .41 |

| Avoidant | .51 | −.60 | −.17 | −.03 | −.33 | .48 | .55 | .26 | −.01 | .37 |

| Dependent | .41 | −.20 | −.03 | −.07 | −.26 | .54 | .26 | .31 | .07 | .42 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | .21 | −.13 | −.04 | −.20 | .02 | .28 | .25 | .29 | .20 | .21 |

|

| ||||||||||

| % Positive (p < .01) | 83 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 92 | 89 | 97 | 58 | 100 |

| % Negative (p < .01) | 0 | 69 | 31 | 72 | 81 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| % Non-significant | 17 | 28 | 69 | 19 | 19 | 8 | 11 | 3 | 42 | 3 |

Note. N = 336. All correlations > |.15| are significant (p < .01). Correlations > |.50| (i.e., large effect size) are in bold. Significant correlations that are indicative of bipolarity are underlined. N = Neuroticism, E = Extraversion, O = Openness, A = Agreeableness, C =Conscientiousness, NA = Negative Affect, DET = Detachment, ANT = Antagonism, DIS = Disinhibition, PSY = Psychoticism.

Nonlinear Relations with Impairment

The standardized quadratic (i.e., curvilinear) regression coefficient for each trait-impairment regression is presented in Table 3. In all cases, the linear trait-impairment relationship was controlled; thus the effects in Table 3 represent the unique predictive value of the quadratic effect. Due to the large number of regression models and sample size, an alpha-level of .01 was chosen for significance tests. There were a number of instances where regression assumptions were violated, mostly with the MINI variables. In most cases, these violations could be remediated through variable transformation or outlier deletion; no curvilinear effects became significant through remediation. In some cases, remediation failed (e.g., transformations were ineffective); these failures are indicated in Table 3 with superscripts.

Table 3.

Standardized Polynomial Regression Coefficients

| NEO-PI-3FH

|

PID-5

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | O | A | C | NA | DET | PSY | ANT | DIS | |

| General Impairment | ||||||||||

| (−)SWLS | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| MDA Total | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.13 | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.03 |

| WHODAS Total | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| IIP-SC | ||||||||||

| Domineering | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Vindictive | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Coldness | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.03 | −0.12 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.11 | −0.01 |

| Socially Avoidant | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.08 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 | −0.03 |

| Nonassertive | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Exploitable | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Overly Nurturant | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Intrusive | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.06 |

| Total | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| MINI-6 | ||||||||||

| Major Depression | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Mania | −0.10 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 |

| Dysthymia | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.01a | −0.02 |

| Panic Disorder | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| Social Anxiety | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02a | −0.03a | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02a | 0.00 |

| Obsessive Comp. | 0.07a | 0.01a | −0.05a | −0.08a | 0.01a | 0.10 | −0.05a | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Post-Tra. Stress | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 |

| Gen. Anxiety | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Alcohol Use | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Substance Use | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Current Psychosis | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.01a | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Life. Psychosis | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.03a | −0.08 | 0.03a | −0.01a | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Schizophrenia | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.14 | 0.06 | −0.01 |

| Suicidality | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.07 |

| SCID-II | ||||||||||

| Paranoid | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Schizoid | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| Schizotypal | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.05 |

| Antisocial | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.06 |

| Borderline | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.07 | 0.00 | −0.08 |

| Histrionic | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Narcissistic | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Avoidant | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.04 |

| Dependent | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Obsessive-Comp. | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

Note. N = 336. N = Neuroticism, E = Extraversion, O = Openness, A = Agreeableness, C =Conscientiousness, NA = Negative Affect, DET = Detachment, ANT = Antagonism, DIS = Disinhibition, PSY = Psychoticism. Significant (p < .01) standardized regression coefficients are in bold.

= Regression assumptions were violated and could not be remediated.

Across traits, the average absolute standardized coefficient (i.e., |β|) ranged from 0.03 to 0.05, and 14 effects (out of 360; 3.8%) were significant. For the NEO-PI-3FH, only neuroticism (1 effect) and conscientiousness (4 effects) yielded significant quadratic effects. All PID-5 domains, except negative affect, demonstrated at least one significant quadratic effect: Detachment had one, psychoticism had five, antagonism had two, and disinhibition had one. In order to better understand these relationships, nonparametric locally weighted regression plots were examined for trait-impairment relations showing significant quadratic effects using the SAS (version 9.4) PROC LOESS procedure. No plot strongly supported trait bipolarity. To illustrate, three examples of these plots are displayed in Figure 1 (panels b–d). Panel (a) of Figure 1 is based on simulated data and displays a curvilinear relationship that would provide strong evidence for a trait’s bipolarity. Panels (b)–(d) show the three chosen loess plot results. Only the relationship between antagonism and schizoid PD remotely resembles a U-shaped curve, the rest depict acceleration (e.g., stronger trait-impairment relationship at higher values of a trait).

Discussion

The present study examined whether traits are maladaptively bipolar and the breadth of dysfunction opposing trait poles relate to, as indicated by both linear and nonlinear relationships with psychopathology and impairment. Consistent with our hypotheses, linear relations provided little evidence of traits being maladaptively bipolar, and the evidence that did emerge suggested that the maladaptive bipolarity of NEO-PI-3FH extraversion and agreeableness is uneven, with one trait pole being related to an array of dysfunction indicators and the other being related to relatively few. Significant nonlinear trait-maladaptivity relations were scarce, and those found were inconsistent with both high and low extremes being maladaptive.

Evidence for and against Maladaptive Bipolarity

Several correlations provided evidence for maladaptive bipolarity. First, extraversion had a nearly moderate positive relation to HPD, replicating previous meta-analytic work (Samuel & Widiger, 2008) and research with clinicians (Samuel & Widiger, 2004); however, the broader literature adds complexity to this association. Previous research (De Fruyt et al., 2013; Wright & Simms, 2014; Crego & Widiger, 2016) suggests HPD-related traits (e.g., attention-seeking) are difficult to place in structural models, often having moderate-to-strong relations with both extraversion and agreeableness. This raises the question of which aspects of HPD align with each trait. Gore, Tomiatti, and Widiger (2011) explored this issue using numerous HPD measures, finding that (a) the HPD-agreeableness relation is most robust and (b) the HPD-extraversion relation is strongest with HPD measures that emphasize normal-range as opposed to pathological personality traits. This interpretation is supported by high extraversion’s lack of correlation with interpersonal problems, despite HPD relating to interpersonal problems (e.g., Williams & Simms, 2016). Although noting a client’s high extraversion may still be of clinical import (e.g., Widiger & Presnall, 2013), it remains unclear whether high extraversion alone is maladaptive.

Second, agreeableness demonstrated weak positive correlations with warm-submissive interpersonal problems, suggesting individuals high in agreeableness are somewhat more likely to be overly deferent or concerned with others’ needs. This finding aligns with theoretical expectations (e.g., Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009), though previous research regarding this effect has been inconsistent (e.g., Schmitz, Hartkamp, Baldini, Rollnik, & Tress, 2001). Structural analyses tend to place potential maladaptive agreeableness scales under neuroticism (e.g., Wright & Simms, 2014); however, FFM research (e.g., Gore, Presnall, Miller, Lynam, & Widiger, 2012; Gore & Widiger, 2015) indicates as many as six potentially overlooked maladaptive high agreeableness facets (Lynam, 2012). Notably, Crego and Widiger (2016) examined three such facets (along with other FFM facets) in joint factor analyses with the PID-5 and CAT-PD, finding that only one facet, timorousness, consistently loaded on an agreeableness factor. Only one other study has examined FFM timorousness, with the main finding being that it did not have its hypothesized relations to avoidant PD or social anxiety (Lynam, Loehr, Miller, & Widiger, 2012). Further work is needed to better understand the relevance of timorousness to personality pathology and consider other proposed maladaptive agreeableness facets.

In contrast, neuroticism, conscientiousness, openness, and all PID-5 traits showed only unidirectional correlations. Furthermore, all traits related to a broader array of maladaptive outcomes at one pole (e.g., low agreeableness correlated with HPD, paranoid PD, and major depression symptoms) and these relationships tended to be of stronger magnitude. These results are consistent with meta-analyses of trait relations to psychopathology (Kotov et al., 2010; Samuel & Widiger, 2008), as well as research relating traits to measures of functioning (e.g., Calabrese & Simms, 2014; Ro & Clark, 2013). Somewhat unexpected was the lack of evidence for maladaptively high conscientiousness, which has been indicated via relations to criterion variables (e.g., Carter et al., 2016; Samuel & Widiger, 2008), clinician ratings (Samuel & Widiger, 2004), structural analyses (Wright & Simms, 2014), and scale development (e.g., Crego, Samuel, & Widiger, 2015). The present study may have lacked the proper functioning variables (e.g., job satisfaction; Carter et al., 2016), inadequately measured OCPD, or missed a result that would be more evident at the facet-level (Carter et al., 2016). Additionally, openness to experience may be maladaptively bipolar (Piedmont, Sherman, Sherman, Dy-Liacco, & Williams, 2009); however, its bipolarity is likely contingent upon its relation to psychoticism, which is controversial (e.g., Wright & Simms, 2014). Overall, considering the present results and the broader literature, the strongest evidence for maladaptive bipolarity exists for conscientiousness and agreeableness; however, it appears that the low ends of these traits related to a broader array of dysfunction.

Advancing Perspectives on Maladaptive Bipolarity

The present study and previous research suggest broad personality domains are predominantly maladaptive at one extreme; however, high conscientiousness and agreeableness can be maladaptive at opposing extremes. These findings would seem to conflict with accounts that suggest that (a) all FFM traits are maladaptively bipolar (e.g., Samuel, 2011; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009) and (b) maladaptively bipolar traits should be measured with equal resolution at both extremes (e.g., capturing varied manifestations of a maladaptive trait pole through narrower facets; Rojas & Widiger, 2014).

In addition, these conclusions suggest that the DSM-5 Section III trait model aligns reasonably well with maladaptive bipolarity research; however, potential discrepancies should be noted. For instance, maladaptive conscientiousness may be underrepresented, in that there is only one such facet in the model (i.e., rigid-perfectionism; Krueger et al., 2012). Indeed, some evidence suggests that the trait workaholism meaningfully improves the DSM-5 model’s representation of maladaptive conscientiousness (e.g., Wright & Simms, 2014; Yalch & Hopwood, 2016). Additionally, it is possible that DSM-5 submissiveness (a) is misplaced (i.e., under negative affectivity) and (b) underrepresents maladaptive agreeableness (e.g., a timorousness facet is needed); however, further work is needed to confirm this. Future research seeking to add traits to the DSM-5 model should demonstrate that proposed traits are (a) not redundant with existing traits, (b) have practical importance (e.g., incremental predictive validity; Yalch & Hopwood, 2016), and (c) fit logically in the existing factor structure (e.g., Wright & Simms, 2014). Such work will help ensure that research on maladaptive bipolarity influences future DSM revisions (e.g., 5.1).

In addition to recognizing that trait models need to take into account complex realities of mixed (i.e., some traits, not all) and uneven (i.e., one pole dominantly maladaptive) maladaptive bipolarity, it is notable that there is little empirical or theoretical work on why traits are asymmetrically maladaptive. For instance, it may be that the maladaptiveness of a trait pole is strongly influenced by cultural norms, potentially leading one extreme to be more socially consequential than the other (Wakefield, 2006). Such an interpretation is supported by research that finds that English language has more undesirable trait adjectives for Big Five poles that have been typically associated with maladaptivity (e.g., Coker et al., 2002). Alternatively, it may be that this unevenness in undesirable adjectives mirrors real underlying social-cognitive dysfunction (e.g., Goldberg, 1990; Fleeson & Jayawickreme, 2015; Wakefield, 2006), which has a basis in the individual’s temperament or developmental history (e.g., Clark, 2005). Regardless, more attention to such issues will help ground debates on maladaptive bipolarity in traits.

Finally, future work will do well to adequately define maladaptive bipolarity and select appropriate research methods. Factor analysis, although useful, cannot conclusively determine the meaning of positive and negative poles of a dimension (e.g., Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). Also, when developing scales to meaningfully extend normal-range traits to have more pathological content (e.g., Gore & Widiger, 2015), it is important to supplement such studies with structural analyses of the full trait model to demonstrate that the alterations did not substantially change the constructs being measured. This is particularly true in cases where convergent correlations between new scales and their parent scales are low (e.g., < .5; Gore et al., 2012). In addition, both structural analyses and scale development procedures should be supplemented with criterion validity analyses, which include variables that represent impairments hypothesized to exist at the trait pole in question. In demonstrating criterion validity, polynomial regression may be necessary to uncover effects indicative of bipolarity (e.g., Carter et al., 2016), particularly when the criterion is a general functioning variable (e.g., theoretically, high and low agreeableness might both relate to poor relationship outcomes). All such data should be integrated into a complete understanding of maladaptive bipolarity in traits.

Limitations

The present study used a large clinical sample, numerous maladaptivity indicators, multiple assessment methods, and analyzed nonlinear trait-maladaptivity relationships; however, despite these strengths, this study also should be understood in the context of its limitations. First, despite multi-method assessment of maladaptivity, traits were only assessed via self-report and thus may miss important information about individuals’ personalities (e.g., Vazire, 2010); future work is needed to replicate these findings using informant reports. Second, recently developed FFM measures (e.g., Crego et al., 2015; Rojas & Widiger, 2014) have been developed to assess the maladaptive extremes of FFM facets; using scales from such measures may have yielded different results, such as indicating stronger maladaptivity for conscientiousness. However, as mentioned above, some of these maladaptive scales have low convergent correlations with their respective normal-range peers (e.g., Gore et al., 2012), and little factor analytic work (Crego & Widiger, 2016) has examined their placement within broader trait models. Third, despite examining an array of dysfunction indicators, it is possible that relevant variables were not assessed (e.g., job satisfaction; Carter et al., 2015). Although future work should expand the scope of dysfunction assessed, it should be noted that truly maladaptive traits would be expected to interfere with general functioning, which were assessed here.

Fourth, examining facets may have indicated traits within domains that relate to dysfunction in opposing directions, suggesting maladaptive bipolarity (e.g., Carter et al., 2016); however, it is unclear whether such an analysis is informative about the broader domain. Personality trait domains generally are conceptualized in terms of variance shared by facets; however, facets themselves have unique variance, which may be accounted for by other personality domains (e.g., Bäckström, Larsson, & Maddux, 2009) or unique constructs. Finally, recent research (Carter et al., 2016) has demonstrated an advantage for ideal point item response modeling for detecting curvilinear relationships between traits and functioning; however, such methods require larger sample sizes and, based on previous results (Carter et al., 2016; 2017), such scoring methods alone likely would not have grossly altered the present findings.

Conclusions

The present study examined whether broad trait domains are maladaptive at one pole (i.e., unipolar) or both poles (i.e., bipolarity) of their dimensions. Correlations and polynomial regressions with psychopathology and functioning variables suggested that, traits are predominately maladaptive at one extreme. Extraversion demonstrated at moderate positive relation to HPD, but previous research calls into question whether this truly indicates maladaptivity. Some evidence was also found for maladaptive high agreeableness. The present results and broader literature generally support the current DSM-5 Section III trait model, but also suggest possible areas for its improvement, such as attempting to increase the model’s coverage of maladaptively high conscientiousness. Overall, it is recommended that the discussion surrounding maladaptive bipolarity will benefit from shifting the dichotomous “bipolar vs. unipolar” focus to one that additionally considers the likely asymmetrical distribution of maladaptivity in opposing trait poles.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lew Goldberg, David Watson, John Roberts, John Welte, William Calabrese, Jane Rotterman, Monica Rudick, Aidan Wright, Wern How Yam, and Kerry Zelazny for their support of the broader project from which these data were drawn.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Grant R01MH080086 from the National Institute of Mental Health to L. J. Simms.

Footnotes

The original sample consisted of 695 participants; 67 were excluded due to inconsistent responding, extensive missing data, and in-session behavior (e.g., intoxication) suggestive of invalid responding.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Selbom M, Bagby RM, Quilty LC, Veltri COC, Markon KE, Kruger RF. On the convergence between PSY-5 domains and PID-5 domains and facets: Implications for assessment of DSM-5 personality traits. Assessment. 2013;20:286–294. doi: 10.1177/1073191112471141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström M, Larsson MR, Maddux RE. A structural validation of an inventory based on the abridged five factor circumplex model (AB5C) Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91:462–472. doi: 10.1080/00223890903088065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce CJ, Wood AM, Brown GDA. The dark side of conscientiousness: Conscientious people experience greater drops in life satisfaction following unemployment. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:535–539. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese WR, Simms LJ. Prediction of daily ratings of psychosocial functioning: Can ratings of personality disorder traits and functioning be distinguished? Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2014;5:314–322. doi: 10.1037/per0000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter NT, Dalal DK, Guan L, LoPilato AC, Withrow SA. Item response theory scoring and the detection of curvilinear relationships. Psychological Methods. 2017;22:191–203. doi: 10.1037/met0000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter NT, Guan L, Maples JL, Williamson RL, Miller JD. The downsides of extreme conscientiousness for psychological well-being: The role of obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Journal of Personality. 2016;84:510–522. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorder: Perennial issues and an emerging reconceptualization. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:227–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coker LA, Samuel DB, Widiger TA. Maladaptive personality functioning within the Big Five and the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:385–401. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.5.385.22125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Crego C, Samuel DB, Widiger TA. The FFOCI and other measures and models of OCPD. Assessment. 2015;22:135–151. doi: 10.1177/1073191114539382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crego C, Widiger TA. Convergent and discriminant validity of alternative measures of maladaptive personality traits. Psychological Assessment. 2016;28:1561–1575. doi: 10.1037/pas0000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin. 1955;52:281. doi: 10.1037/h0040957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daspe M, Sabourin S, Péloquin K, Lussier Y, Wright J. Curvilinear associations between neuroticism and dyadic adjustment in treatment-seeking couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:232–241. doi: 10.1037/a0032107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F, De Clerq B, De Bolle M, Wille B, Markon K, Krueger RF. General and maladaptive traits in a five-factor framework for DSM-5 in a university student sample. Assessment. 2013;20:295–307. doi: 10.1177/1073191113475808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson W, Jayawickreme E. Whole trait theory. Journal of Research in Personality. 2015;56:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JC, Sharp C, Kapakci A, Madan A, Clapp J, Allen JG, Frueh BC, Oldham JM. A dimensional approach to assessing personality functioning: Examining personality trait domains utilizing DSM-IV personality disorder criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2015;56:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. An alternative “description of personality”: The Big Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:1216–1229. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.6.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore WL, Presnall JR, Miller JD, Lynam DR, Widiger TA. A five-factor measure of dependent personality traits. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2012;94:488–499. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.670681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore WL, Tomiatti M, Widiger TA. The home for histrionism. Personality and Mental Health. 2011;5:57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gore WL, Widiger TA. Assessment of dependency by the FFDI: Comparisons to the PID-5 and maladaptive agreeableness. Personality and Mental Health. 2015;9:258–276. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AM. Rethinking the extraverted sales ideal: The ambivert advantage. Psychological Science. 2013;24:1024–1030. doi: 10.1177/0956797612463706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigler ED, Widiger TA. Experimental manipulation of NEO-PI-R items. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2001;77:339–358. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7702_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness AR, McNulty JL. The Personality Psychopathology Five (PSY–5): Issues from the pages of a diagnostic manual instead of a dictionary. In: Strack S, Lorr M, editors. Differentiating normal and abnormal personality. New York, NY: Springer; 1994. pp. 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Wright AGC, Krueger RF, Schade N, Markon KE, Morey LC. DSM-5 pathological personality traits and the personality assessment inventory. Assessment. 2013;20:269–285. doi: 10.1177/1073191113486286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosek RB. Couples Critical Incidents Checklist: A construct validation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1998;54:785–794. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199810)54:6<785::aid-jclp5>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, Watson D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:768–821. doi: 10.1037/a0020327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Derringer R, Markon KE, Watson D, Skodol AE. Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:1879–1890. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Eaton NR, Clark LA, Watson D, Markon KE, Derringer J, Skodol A, Livesley WJ. Deriving an empirical structure of personality pathology for DSM-5. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2011;25:170–191. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le H, Oh I, Robbins SB, Ilies R, Holland E, Westrick P. Too much of a good thing: Curvilinear relationships between personality traits and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2011;96:113–133. doi: 10.1037/a0021016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loevinger J. Objective tests as instruments in psychological theory. Psychological Reports. 1957;3:635–694. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR. Assessment of maladaptive variants of five-factor model traits. Journal of Personality. 2012;80:1593–1614. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Loehr A, Miller JD, Widiger TA. A five-factor measure of avoidant personality: The FFAvA. Journal of personality assessment. 2012;94:466–474. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.677886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Brief versions of the NEO-PI-3. Journal of Individual Differences. 2007;28:116–128. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT, Jr, Martin TA. The NEO-PI-3: A more readable Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2005;84:261–270. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8403_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins-Sweatt SN, Widiger TA. Personality-related problems in living: An empirical approach. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatments. 2010;1:230–238. doi: 10.1037/a0018228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer DJ, Benet-Martínez V. Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:401–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL, Sherman MF, Sherman NC, Dy-Liacco GS, Williams JEG. Using the five-factor model to identify a new personality disorder domain: The case for experiential permeability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:1245–1258. doi: 10.1037/a0015368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro E, Clark LA. Psychosocial functioning in the context of diagnosis: Assessment and theoretical issues. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:313–324. doi: 10.1037/a0016611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro E, Clark LA. Interrelations between psychosocial functioning and adaptive- and maladaptive-range personality traits. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:822–835. doi: 10.1037/a0033620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas SL, Widiger TA. Convergent and discriminant validity of the five factor form. Assessment. 2014;21:143–157. doi: 10.1177/1073191113517260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Costa PT, Jr, Bagby RM. Evaluation of the SCID-II personality disorder traits for DSM-IV: Coherence, discrimination, relations with general personality traits and functional impairment. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:626–637. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB. Assessing personality in DSM-5: The utility of bipolar constructs. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2011;93:390–397. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.577476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. Clinician’s descriptions of prototypic personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:286–308. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.3.286.35446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1326–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Hartkamp N, Baldini C, Rollnik J, Tress W. Psychometric properties of the German version of the NEO-FFI in psychosomatic outpatients. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:713–722. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms LJ, Goldberg LR, Roberts JE, Watson D, Welte J, Rotterman JH. Computerized adaptive assessment of personality disorder: Introducing the CAT-PD project. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2011;93:380–389. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.577475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldz S, Budman S, Demby A, Merry J. Representation of personality disorders in circumplex and five-factor space: Explorations with a clinical sample. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Rehm J, Kennedy C, Epping-Jordan J, Saxena S, von Korff M, Pull C. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:815–823. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.067231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, Bartak A, Widiger T. Prevalence and construct validity of personality disorder not otherwise specified (PDNOS) Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:359–370. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield JC. Personality disorders as harmful dysfunction: DSM’s cultural deviance criterion reconsidered. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20:157–169. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Mullins-Sweatt SN. Five-Factor Model of personality disorder: A proposal for DSM-V. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:197–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Presnall JR. Clinical application of the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality. 2012;81:515–527. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TF, Simms LJ. Personality disorder models and their coverage of interpersonal problems. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2016;7:15–27. doi: 10.1037/per0000140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Hopwood CJ, Simms LJ. Daily Interpersonal and Affective Dynamics in Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2015;29:503–525. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2015.29.4.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Simms LJ. On the structure of personality disorder traits: Conjoint analyses of the CAT-PD, PID-5, and NEO-PI-3 trait models. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2014;5:43–54. doi: 10.1037/per0000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalch MM, Hopwood CJ. Convergent, discriminant, and criterion validity of DSM–5 traits. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2016;7:394–404. doi: 10.1037/per0000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1911–1918. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]