Abstract

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is characterized by gastrointestinal and ectodermal manifestations. In this paper, we describe a 64-year-old Iranian male, presenting with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with metastatic colon cancer. The patient was suffering from hair loss, which occurred on the scalp at first and then, during 5 months, extended to the whole body. After that, his sense of taste was impaired, and 2 months later, gastrointestinal symptoms gradually started, with weight loss of 20 kg over 2 months with an initial weight of 100 kg. Finally, he was admitted to our center 10 months after the onset of symptoms. On skin examination, generalized hair loss and hyperpigmentation and dysmorphic nail changes were observed. Multiple polyps within the colon and sigmoid were observed on colonoscopy. According to biopsies, a serrated adenoma and an invasive adenocarcinoma were reported in the ascending colon and sigmoid, respectively. Other polyps were pseudopolyps, and their characteristics were not significant. Computed tomography of the lungs and abdomen showed multiple adenopathies. On biopsy, metastatic adenocarcinoma was reported. The patient underwent chemotherapy with FOLFIRI and ERBITUX. Finally, after 5 courses of chemotherapy, his regimen was changed to FOLFOX and Avastin because of evidence of progression on computed tomography. The etiology of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is currently unknown, and the optimal therapy has not been reported so far. This syndrome has many complications; the major of them is malignancy, and the prognosis is poor with a mortality rate of 50%. Therefore, annual monitoring is necessary in these patients.

Keywords: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, Polyposis, Generalized hair loss, Colorectal cancer

Introduction

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare noninherited disorder that was reported for the first time in 1955 by Leonard Wolsey Cronkhite Jr. and Wilma Jeanne Canada [1]. Over 500 cases have been reported worldwide, the majority of them being reported from Japan [2, 3]. This syndrome is characterized by gastrointestinal polyposis in the stomach, small bowel, colon, and, very rarely, the esophagus [4]. Other manifestations are diarrhea, taste disturbance, alopecia, hyperpigmentation, and dystrophic changes of the fingernails [3]. Differential diagnoses of this syndrome are other polyposis syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cowden disease, hyperplastic polyposis, juvenile polyposis, and Turcot syndrome [5]. The etiology is still unknown, although some authors have suggested an autoimmune process and psychological stress [6, 7]. It is believed that no specific treatment has resulted in definite improvement, and, usually, the available management includes nutritional support, supplemental therapy, acid suppression, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, etc. [8, 9]. This syndrome has many complications, some of which are potentially fatal [5]. The major problem associated with CCS is malignancy with a rate of 5–25% [3, 10]. So far, 2 cases of this syndrome without malignancy have been reported in Iran, and in this study, we describe a 64-year-old Iranian male presenting with CCS with metastatic colon cancer [11, 12].

Case Presentation

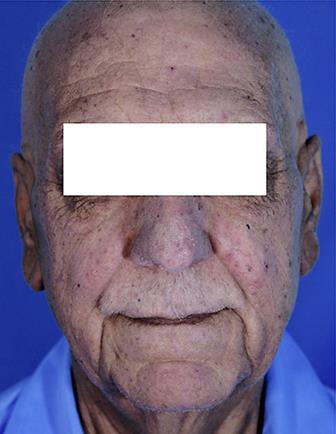

A 64-year-old Iranian man was suffering from hair loss (Fig. 1), which occurred on the scalp at first and then, during 5 months, extended to the whole body. After a cutaneous assessment and use of topical medicine, no response was achieved during 2 months. After 7 months, his sense of taste was impaired, and 2 months later, gastrointestinal symptoms, i.e., abdominal pain, gradually started in the area of the epigastrium and the periumbilical region, with bloody watery diarrhea and a weight loss of 20 kg over 2 months with an initial weight of 100 kg. Gastrointestinal symptoms lasted for 1 month, and, finally, he was admitted to our center 10 months after the onset of symptoms. His family history was negative for any underlying medical condition, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, and gastrointestinal diseases, such as peptic ulcers, gastrointestinal cancer, or polyposis syndrome. He was a nonsmoker and nondrinker without a history of drug abuse. On physical examination, vital signs were stable, and general appearance was good. Generalized hair loss and hyperpigmentation and dysmorphic nail changes were observed (Fig. 2). Edema was observed in the lower extremities. On other examinations, no more signs were found.

Fig. 1.

Hair loss.

Fig. 2.

Dysmorphic changes of nails.

Laboratory findings showed that the patient had hypoproteinemia (total protein = 4.5 g/dL; normal: 6.3–8.4 g/dL), hypoalbuminemia (albumin = 2.8 g/dL; normal: 3.5–5.2 g/dL), hypocalcemia (Ca = 7 mg/dL; normal: 1.2–6.2 mg/dL), and zinc deficiency (Zn = 60 μg/dL; normal: 72.6–127 μg/dL). Other values were: lactate dehydrogenase = 552 IU/L (normal: 140–280 IU/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate = 80 mm/h (normal range for men over 50 years old: < 20 mm/h), C-reactive protein = 113.3 mg/L (normal: up to 6 mg/L), antinuclear antibody (ANA) = 1.6 U (positive: > 1 U, negative: < 1 U), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) = 34 mIU/mL (normal: 0.25–5 mIU/mL). Tumor markers were as follows: carcinoembryonic antigen = 2 ng/mL (nonsmoker: < 5 ng/mL, smoker: < 10 ng/mL), cancer antigen 125 = 1 (normal: up to 35), and alpha-fetoprotein = 6.6 ng/mL (normal: 0.2–8.5 ng/mL). Occult blood test was negative, and other parameters, such as fasting blood sugar, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum IgG4, liver function tests, and electrolytes, were all in a normal range.

According to most studies about CCS, all of the mentioned clinical presentations of the patient are common in this syndrome. In addition, all of the abnormal findings in the laboratory data can be seen in the syndrome, but some data can be abnormal that in this case were normal, such as electrolytes and complete blood count.

The patient underwent endoscopy and colonoscopy with biopsies, which revealed multiple erosions in the antrum and the body of the stomach. Based on the biopsies, gastritis, duodenitis, and Helicobacter pylori infection were reported. Multiple polyps within the colon and sigmoid were observed on colonoscopy. One polyp was observed in the ascending colon, a small sessile polyp in the transverse colon, and a large polyp in the rectum. In addition, a large ulcerative mass was found in the sigmoid, and according to biopsies, a serrated adenoma and an invasive adenocarcinoma were reported in the ascending colon and in the sigmoid, respectively. Other polyps were pseudopolyps, and their characteristics were not significant.

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the lungs and abdomen showed multiple adenopathies. On biopsy, metastatic adenocarcinoma was reported. Microsatellite instability (MSI) was negative by immunohistochemistry. A survey of pathology samples was performed, and NRAS and KRAS were reported to be wild type.

Based on history, clinical findings, and laboratory studies, the patient was diagnosed with CCS with metastatic colon cancer. The patient received chemotherapy with FOLFIRI (folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan) and cetuximab (ERBITUX). Finally, after 5 courses of chemotherapy, his regimen was changed to FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil) and bevacizumab (Avastin) because of evidence of progression on the patient's CT scan.

Discussion

CCS is a rare noninherited disorder that was reported for the first time in 1955 by Leonard Wolsey Cronkhite Jr. and Wilma Jeanne Canada [1]. Over 500 cases have been reported worldwide [2]; the majority of them were European or Asian, and most of the cases (75%) were reported from Japan [3]. There was no evidence suggesting the influence of genetic, environmental, or infectious causes in a Japanese population [13]. The estimated incidence of CCS is extremely rare; 1 per million according to a large study on CCS involving 110 patients. The average age of onset is between 40 and 60 years of age, and it is more prevalent in males by a ratio of 3 to 2. The most common symptoms of this syndrome are multiple polyps in the gastrointestinal tract, diarrhea, taste disturbance, dysmorphic nail changes, hyperpigmentation, and alopecia [3]. So, differential diagnoses of this syndrome are other polyposis syndromes. Gastrointestinal polyps are closely related to malabsorption which induces ectodermal changes. Taste disturbance can happen due to zinc and copper deficiency [5]. According to the laboratory results, malabsorption of zinc, calcium, albumin, and total protein was present in this patient. Based on the Goto case series study, patients can be divided into 5 types according to the leading symptom: diarrhea (type 1), dysgeusia (type 2), sensory abnormalities in the mouth accompanied by thirst (type 3), abdominal symptoms other than diarrhea (type 4), and alopecia as a predominant symptom (type 5) [10]. Based on these categories, our patient had type 5 disease.

The etiology of this syndrome is currently unknown, and there is no evidence of a hereditary background, except for 1 case in India. Nevertheless, it seems that an autoimmune reaction and infectious agents are involved in the development of the disease [6]. Recent reports have shown that autoimmune diseases, such as hypothyroidism, systemic lupus erythematous, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma, and also increased levels of ANA and IgG4 antibody are significantly associated with CCS [3, 5]. In our patient, IgG4 antibody was normal, but ANA was positive, and based on the laboratory report, TSH was high. H. pylori was also positive and, according to some studies, eradication of H. pylori infection can improve CCS. So, it seems that there is an association between H. pylori infection and CCS [6]. Based on a comprehensive study in Japan, psychological stress and physical fatigue are also predisposing factors for this disease [7].

At first, CCS was considered to be a hamartomatous polyposis syndrome. But today, it is known that the polyps can present as an inflammatory, an adenomatous, and a hyperplastic type [6]. Because of a considerable overlap between the endoscopic and histologic characteristics of CCS polyps and other polyposis syndromes, a CCS diagnosis should always be made based on clinicopathologic, and not merely histologic, evidence [14].

Common complications of CCS are anemia, intussusception, rectal prolapse, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Some uncommon complications are recurrent severe acute pancreatitis, myelodysplastic syndrome, cecal intussusception, portal thrombosis, and membranous glomerulonephritis [5]. The major problem of CCS is malignancy [3]. As another complication, osteoporotic fractures may result from malabsorption of calcium or prolonged glucocorticoid therapy or both [6, 15]. The prognosis of CCS is poor with a mortality rate of 50%. The patients usually die from gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia, septicemia, severe cachexia, embolism, bronchopneumonia, shock, congestive heart failure, and postoperative complications [16, 17].

As we have noted, the most important problem associated with CCS is malignancy, and the risk of gastric and colon cancer with CCS is estimated to be 5–25% [10], especially in the left colon [14]. It seems that these patients have a tendency for malignancies of the gastrointestinal system, such as cholangiocellular carcinoma, and for giant cell bone tumor and lung cancer [6]. In addition, some cases of CCS have been associated with cancer in more than one organ [10, 13, 18].

Due to the unknown etiology of the disease, an optimal therapy has not been reported. Also, there are no available data on controls, so the success rate with treatment cannot be predicted [8]. Combination therapy is a treatment that has been presented in various reports. It includes nutritional support, supplemental therapy, acid suppression, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, and anti-tumor necrosis factor. H. pylori infection has also been reported to be related to CCS, and eradication of H. pylori seems to improve symptoms in some cases. In addition, surgical therapy was successful in some reports [7, 8, 17, 19]. Our patient suffered from metastatic colon cancer with CCS; therefore, other therapies were not effective, and the patient received chemotherapy with FOLFIRI (folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan) and cetuximab (ERBITUX). Finally, after 5 courses of chemotherapy, his regimen was changed to FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil) and bevacizumab (Avastin) because of evidence of progression on CT scan.

By the end of 2000, 34 cases of CCS associated with colorectal cancer were reported [9]. According to other studies during 2000–2013 in Japan, 41 cases of CCS associated with colorectal cancer were reported [19]. In addition, from 2013 to 2015, 2 new cases were reported; thus, combined with our case, overall, 78 cases of CCS associated with colorectal cancer have been reported [10, 15]. Regarding the sum of these cases and that, so far, more than 500 cases of CCS have been reported, we can say that the incidence of cancer in this syndrome is 15.6%.

In this context, there is still controversy as to whether cancer is a random occurrence or whether polyps are benign at first and then become malignant. In some studies, as a precursor lesion for adenocarcinoma, serrated adenoma has been reported, which, compared to other polyps, can be seen much more commonly in CCS than in general polyps [4]. For the first time, Vogelstein et al. [20] described the adenoma-carcinoma sequence in 1998, and some studies accepted this theory [5, 19]. In our patient, in addition to the sigmoid carcinoma, a serrated adenoma was found in the ascending colon.

Other causes of malignancy can also be the mutations that occur in inflammation. Therefore, corticosteroids are considered the mainstay of medical treatment for CCS; they can have an effect on the regression of polyps and reduce the risk of malignancy [19]. In our patient, as mentioned above, both malignancy and serrated adenoma were present. In contrast with some studies which suggested that malignant lesions were MSI positive, in the case we reviewed, MSI was negative by immunohistochemistry [5].

Conclusion

Cancer is a major complication of CCS, and its incidence is on the rise. Therefore, annual monitoring is necessary in these patients [3, 19].

Statement of Ethics

All procedures and data gathering were performed with the patient's informed consent.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Samoha S, Arber N. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Digestion. 2005;71:199–200. doi: 10.1159/000086134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubio CA, Björk J. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome – a case report. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:4215–4217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kao KT, Patel JK, Pampati V. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a case report and review of literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:619378. doi: 10.1155/2009/619378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samet JD, Horton KM, Fishman EK, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: gastric involvement diagnosed by MDCT. Case Rep Med. 2009;2009:148795. doi: 10.1155/2009/148795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopáčová M, Urban O, Cyrany J, Laco J, Bureš J, Rejchrt S, Bártová J, Tachecí I. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:856873. doi: 10.1155/2013/856873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu YQ, Whorwell PJ, Wang LH, Li JX, Chang Q, Meng J. Cases report the Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: improving the prognosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e2356. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yun SH, Cho JW, Kim JW, Kim JK, Park MS, Lee NE, Lee JU, Lee YJ. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with serrated adenoma and malignant polyp: a case report and a literature review of 13 Cronkhite-Canada syndrome cases in Korea. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:301–305. doi: 10.5946/ce.2013.46.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.She Q, Jiang JX, Si XM, Tian XY, Shi RH, Zhang GX. A severe course of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and the review of clinical features and therapy in 49 Chinese patients. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2013;24:277–285. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2013.0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murata I, Yoshikawa I, Endo M, Tai M, Toyoda C, Abe S, Hirano Y, Otsuki M. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of two cases. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:706–711. doi: 10.1007/s005350070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamanouchi K, Sakata Y, Tsuruoka N, Shimoda R, Uchida M, Akutagawa T, Shirai S, Fujimoto K, Iwakiri R. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated by triple primary cancers. Intern Med. 2016;55:1569–1573. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safari MT, Shahrokh S, Ebadi S, Sadeghi A. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome; a case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:58–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arab P, Vahedi H. Diagnosis of a rare syndrome: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Govaresh. 2009;14:161–163. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito M, Matsumoto S, Takayama T, Wakatsuki K, Tanaka T, Migita K, Nakajima Y. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with esophageal and gastric cancers: report of a case. Surg Today. 2015;45:777–782. doi: 10.1007/s00595-014-0977-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seshadri D, Karagiorgos N, Hyser MJ. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and a review of gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2012;8:197–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu X, Shi H, Zhou X, Zong Y, Wang J, Xiao J, Zhang Y, Tian Y. A case of recurrent Cronkhite-Canada syndrome containing colon cancer. Int Surg. 2015;100:402–407. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00003.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandyopadhyay D, Hajra A, Ganesan V, Kar SS, Bhar D, Layek M, Mukhopadhyay S, Choudhury C, Choudhary V, Banerjee P. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a rare cause of chronic diarrhoea in a young man. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:4210397. doi: 10.1155/2016/4210397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, Ruprecht RM, Rajacich GM, Schwabe AD. The Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982;61:293–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yashiro M, Kobayashi H, Kubo N, Nishiguchi Y, Wakasa K, Hirakawa K. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome containing colon cancer and serrated adenoma lesions. Digestion. 2004;69:57–62. doi: 10.1159/000076560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe C, Komoto S, Tomita K, Hokari R, Tanaka M, Hirata I, Hibi T, Kaunitz JD, Miura S. Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:327–336. doi: 10.1007/s00535-015-1107-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, Nakamura Y, White R, Smits AM, Bos JL. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]