Abstract

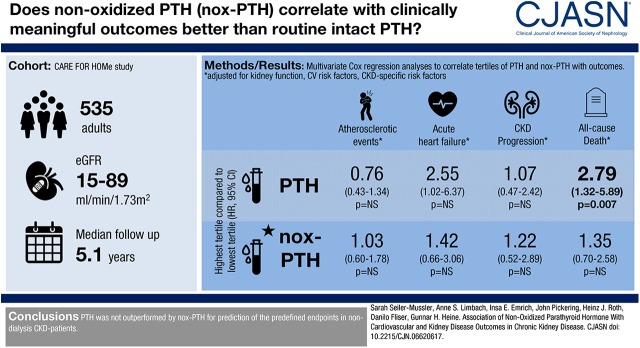

Background and objectives

In patients with CKD, elevated plasma parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels are associated with greater cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. However, the reference method for PTH measurement is disputed. It has been argued that measurement of nonoxidized PTH better reflects biologically active PTH than measurements with conventional assays.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

PTH and nonoxidized PTH levels were measured at study baseline in 535 patients with CKD with an eGFR range between 89 and 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Patients were followed over 5.1 years for the occurrence of acute heart failure, atherosclerotic events, CKD progression (doubling of serum creatinine or initiation of RRT), or all-cause death.

Results

Atherosclerotic events, acute heart failure, CKD progression, and deaths from any cause occurred in 116, 58, 73, and 85 patients, respectively. In Kaplan–Meier analyses, patients at the highest PTH and nonoxidized-PTH tertile (79–543 and 12–172 pg/ml, respectively) showed a higher rate of atherosclerotic events, acute heart failure, CKD progression, and death from any cause. After adjustment for eGFR and albuminuria, nonoxidized PTH was no longer associated with atherosclerotic events (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 1.04 [95% confidence intervals, 0.62–1.75]), acute heart failure (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 1.24 [95% confidence intervals, 0.59–2.62]), CKD progression (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 0.93 [95% confidence intervals, 0.46–1.90]), and death from any cause (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 1.23 [95% confidence intervals, 0.66–2.31]), and PTH lost its association with atherosclerotic events (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 0.80 [95% confidence intervals, 0.46–1.38]) and CKD progression (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 0.99 [95% confidence intervals, 0.46–2.10]), although it remained associated with acute heart failure (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 2.76 [95% confidence intervals, 1.11–6.89]) and all-cause death (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 2.35 [95% confidence intervals, 1.13–4.89]). After further adjustment for cardiovascular and kidney risk factors, PTH remained associated with all-cause death (hazard ratio third versus first tertile, 2.79 [95% confidence intervals, 1.32–5.89]), but with no other end point.

Conclusions

In a cohort of patients with CKD, PTH was associated with all-cause mortality; there was no association of nonoxidized PTH with any of the clinical outcomes examined.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease; chronic kidney disease; clinical epidemiology; Humans; albuminuria; parathyroid hormone; risk factors; creatinine; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; kidney; Cause of Death; Disease Progression; Renal Replacement Therapy; heart failure

Introduction

Patients with CKD suffer from increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (1–3). In addition to traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, smoking, and dyslipidemia, CKD-specific risk factors may play a central role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (4). Among such CKD-specific risk factors, changes in calcium and phosphorus regulation with subsequent vascular calcification and bone abnormalities, which are summarized as “CKD–mineral and bone disorder” (CKD-MBD), may particularly contribute to the cardiovascular disease burden (5).

Secondary hyperparathyroidism with elevated plasma parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a central component in the pathogenesis of CKD-MBD. In the course of CKD, PTH levels rise as soon as eGFR falls below 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Phosphate retention, low plasma calcium, and high FGF-23 with subsequently decreased plasma calcitriol concentration all contribute to the evolvement of secondary hyperparathyroidism (6,7). Elevated levels of PTH were found to be associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with CKD (8,9). In line, lag-censoring analysis of the components of the primary composite outcome from the Evaluation of Cinacalcet Hydrochloride Therapy to Lower Cardiovascular Events (EVOLVE) study revealed a significant decrease in mortality and heart failure by pharmacologic lowering of elevated PTH levels in patients with CKD (10). Consistently, preliminary 2016 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines state that optimal PTH levels for patients with CKD G3a–G5 remain uncertain (5).

Despite the central role of secondary hyperparathyroidism in CKD-MBD, there is no consensus on the reference method for PTH measurement. Different generations of PTH assays have been developed, which detect several diverse PTH fragments to different degrees (11). This issue is further complicated, because patients with CKD are prone to oxidative stress (12,13), and the majority of circulating PTH molecules may become oxidized and thus nonfunctional in uremic patients. The idea of the nonfunctionality of oxidized PTH derives from in vivo and in vitro data suggesting that only nonoxidized PTH is able to activate PTH receptors, and thus to exert physiologic PTH actions, whereas oxidation of methionine residues in position 8 and 18 of PTH will modify its secondary protein structure and impede its interaction with PTH receptors (14,15). Although traditional PTH assays detect both oxidized and nonoxidized PTH, selective measurement of nonoxidized PTH was assumed to provide better information on biologically active hormone levels (16–18).

To grasp the value of nonoxidized PTH (nox-PTH) measurements among patients with CKD not receiving dialysis, we analyzed the prognostic effect of nox-PTH measurements for cardiovascular and kidney outcome in our CArdiovascular and REnal outcome in CKD stage 2-4 patients - the FOuRth HOMburg evaluation (CARE FOR HOMe) study, which comprises patients with CKD with an eGFR range between 89 and 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Particularly, we investigated if nox-PTH measurements were more closely associated with event-free survival than PTH levels measured by an established second-generation PTH assay, which is routinely applied in clinical nephrology.

Materials and Methods

Our ongoing CARE FOR HOMe study recruits patients with CKD with a range of eGFR between 89 and 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 from our outpatient clinic at Saarland University hospital, a tertiary reference center in the state of Saarland situated in southwestern Germany. The study was approved by the local ethics committee; all patients provided written informed consent. The authors adhered to the declaration of Helsinki.

The CARE FOR HOMe study design has been published in detail in earlier manuscripts (19,20). Baseline blood samples were drawn under standardized conditions at study inclusion and processed as described previously (20). Intact PTH was measured by a second-generation electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay (Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland); nox-PTH was measured with the same assay after prior removal of oxidized PTH molecules from the samples. Oxidized PTH (ox-PTH) was removed using affinity chromatography columns (Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany) with a monoclonal antihuman ox-PTH antibody immobilized on Sepharose. Previous experiments demonstrated a high specificity of these mAbs against all forms of human oxidized PTH (17). In brief, columns were centrifuged for 2 minutes at 3000 rpm to remove any PBS buffer from the column before applying 300 µl of plasma sample. After sealing, the columns were incubated, mixing end over end at room temperature for 1 hour. Columns were placed on a sample tube and centrifuged again for 2 minutes at 3000 rpm to collect the eluate. Finally, eluates were analyzed for nox-PTH. The method for the quantitation of the nox-PTH assay was implemented for routine testing in February of 2014 at the Medizinisches Versorgungszentrum Dr. Limbach und Kollegen Heidelberg, Germany. Samples for quality assessment were applied to the same treatment as patient samples. Between-run coefficients of variation were 18% at a nox-PTH mean concentration of 2.8 pg/ml and 11% at a nox-PTH mean concentration of 16 pg/ml, respectively.

As previously described (19,20), C-terminal FGF-23 levels and soluble klotho levels were measured by ELISA technique (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA and Immuno-Biologic Laboratories, Fujiokashi, Gunma, Japan, respectively). Other blood variables were measured by standard laboratory methods. Spot urine samples were used to estimate albumin excretion rate (as albumin-to-creatinine ratio), and fractional excretion of phosphorus (calculated as [urine phosphate×plasma creatinine]/[plasma phosphate×urine creatinine]×100).

Patients are invited annually for follow-up visits to our outpatient clinic. Patients unable or unwilling to follow this invitation, and patients who become dialysis-dependent during follow-up, are contacted for a telephone interview. We analyzed two predefined cardiovascular end points: Firstly, atherosclerotic events, which comprises acute myocardial infarction (defined as a rise in troponin T above the 99th percentile of the reference limit accompanied by symptoms of ischemia and/or electrocardiographic changes indicating new ischemia) (21), surgical or interventional coronary/cerebrovascular/peripheral arterial revascularization, stroke (defined as rapidly developing clinical symptoms or signs of focal [or at times global] disturbance of cerebral function lasting 24 hours [unless interrupted by surgery] or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin) (22), amputation above the ankle, and cardiovascular death. The second cardiovascular end point was acute heart failure, which comprises hospital admission for acute heart failure (defined as admission for a clinical syndrome involving symptoms [progressive dyspnea] in conjunction with clinical [e.g., peripheral edema, pulmonary rales] or radiologic [e.g., cardiomegaly, pulmonary edema, pleural effusions] signs of heart failure). Thirdly, CKD progression, defined as doubling of serum creatinine or the initiation of RRT, was assessed. Finally, we assessed all-cause mortality as a fourth end point.

All cardiovascular events and CKD progression that were reported by study participants or their nearest relatives were verified by medical records from treating physicians. Two nephrologists blinded to the results of measured CKD-MBD parameters adjudicated all events. In the case of disagreement, a third investigator was asked to make a final decision.

For this analysis, patients were followed until July 31, 2016. No patient was lost to follow-up. Patients not reaching an end point were censored at the time of the last annual follow-up visit (for patients who were contacted via phone, at the time of the last serum creatinine measurement by their treating physician).

Among all 544 study participants who had been recruited between September of 2008 and December of 2014, 535 participants had nox-PTH measurements; for technical reasons, nox-PTH was not measured in the remaining nine patients. All 535 participants with nox-PTH measurements were included in these analyses; of those patients, two patients had no FGF-23 measurements, 97 patients had no soluble klotho measurements, and in ten patients 25-OH-vitamin D3 levels were missing.

Statistical Analyses

Data management and statistical analyses were performed with PASW Statistics 18. Categoric variables are presented as percentage of patients and were compared by chi-squared test, as appropriate. Continuous data are expressed as mean±SD and were compared using one-way ANOVA test (partitioning the between-groups sums of squares into trend components). Albuminuria, urinary fractional phosphate excretion, PTH, nox-PTH, pro-BNP, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or log-transformed, as appropriate, because of skewed distribution. Correlation coefficients were calculated by Kendall’s τ test.

After stratifying patients into tertiles by their plasma PTH and plasma nox-PTH, we performed Kaplan–Meier analysis with consecutive log-rank testing for event-free survival. Additionally, unadjusted and multivariable Cox regression analyses with adjustment for potential confounders were conducted in the total study cohort and in subgroups stratified by prevalent diabetes mellitus and elevated CRP, respectively. In Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analyses the diagnostic accuracy of the different CKD-MBD parameters for prediction of the predefined end points within the first 4 years after study inclusion was compared; correlated ROC curves were compared by Delong’s test for significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants stratified by GFR categories are listed in Table 1. Compared with patients with moderate CKD, patients in more advanced CKD stages were significantly older, had a higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, higher urinary albumin excretion, higher urinary fractional phosphate excretion, higher pro-BNP, higher PTH, and higher nox-PTH levels. The intake of β-blockers, active vitamin D, and statins increased with declining kidney function, whereas the percentage of smokers declined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 535 participants in the CArdiovascular and REnal outcome in CKD stage 2-4 patients - the FOuRth HOMburg evaluation study in Saarland, Germany

| Characteristic | Total (n=535) | eGFR Range (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 89–60 (n=111) | 59–45 (n=184) | 44–30 (n=144) | 29–15 (n=96) | ||

| Age, yr | 65±12 | 59±12 | 65±12 | 68±11 | 68±11 |

| Women | 219 (41) | 36 (32) | 83 (45) | 62 (43) | 38 (40) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 169 (32) | 18 (16) | 57 (31) | 63 (44) | 31 (32) |

| DM | 205 (38) | 38 (34) | 72 (39) | 55 (38) | 40 (42) |

| Smoker | 54 (10) | 20 (18) | 14 (8) | 12 (8) | 8 (8) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 46±16 | 69±7 | 52±4 | 38±4 | 23±4 |

| Urinary albumin excretion, mg/g | 31 (8–191) | 21 (7–100) | 18 (6–74) | 45 (10–166) | 139 (37–685) |

| Phosphate, mg/dl | 3.4±0.7 | 3.0±0.5 | 3.3±0.5 | 3.4±0.8 | 3.8±0.7 |

| Urinary fractional phosphate excretion, (%) | 22 (15–31) | 15 (11–20) | 19 (13–25) | 27 (20–34) | 39 (29–47) |

| PTH, pg/ml | 60 (42–91) | 46 (36–61) | 50 (37–67) | 72 (48–108) | 118 (71–177) |

| nox-PTH, pg/ml | 9 (7–13) | 8 (7–10) | 8 (7–11) | 10 (8–14) | 13 (10–19) |

| FGF-23, rU/ml | 99 (64–157) | 64 (47–89) | 79 (57–107) | 128 (92–196) | 179 (140–296) |

| sKlotho, pg/ml | 397 (326–485) | 433 (369–581) | 412 (344–493) | 374 (299–454) | 382 (303–459) |

| 25-OH- vit. D3, (ng/ml) | 23±13 | 23±12 | 23±13 | 23±14 | 23±14 |

| 1,25-(OH)2- vit. D3, (pg/ml) | 30±12 | 36±13 | 30±11 | 29±11 | 25±9 |

| ACE-I | 190 (36) | 33 (30) | 74 (40) | 45 (31) | 38 (40) |

| At1A | 271 (51) | 65 (59) | 90 (49) | 75 (52) | 41 (43) |

| β-blockers | 370 (69) | 60 (54) | 123 (67) | 116 (81) | 71 (74) |

| Active vitamin D medication | 36 (7) | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 14 (10) | 18 (19) |

| Statins | 276 (52) | 42 (38) | 98 (53) | 86 (60) | 50 (52) |

Variables are presented as number of patients (percentage), mean±SD, or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. DM, diabetes mellitus; PTH, intact parathyroid hormone; nox-PTH, nonoxidized parathyroid hormone; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor 23; rU/ml, relative units per ml; sKlotho, soluble klotho; vit., vitamine; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; At1A, angiotensin-II-receptor-subtype-1-antagonists.

We found a moderate correlation between nox-PTH and PTH (r=0.55); moreover, both nox-PTH and PTH were weakly correlated with low eGFR, and with high fractional excretion of phosphorus, 25-OH-vitamin D3, and FGF-23, but not with plasma phosphate and 1,25-(OH)2-vitamin D3 (Supplemental Table 1).

During the median follow-up period of 5.1 years (IQR, 2.8–6.4 years), atherosclerotic events, acute heart failure events, CKD progression, and deaths from any cause occurred in 116, 58, 73, and 85 patients, respectively.

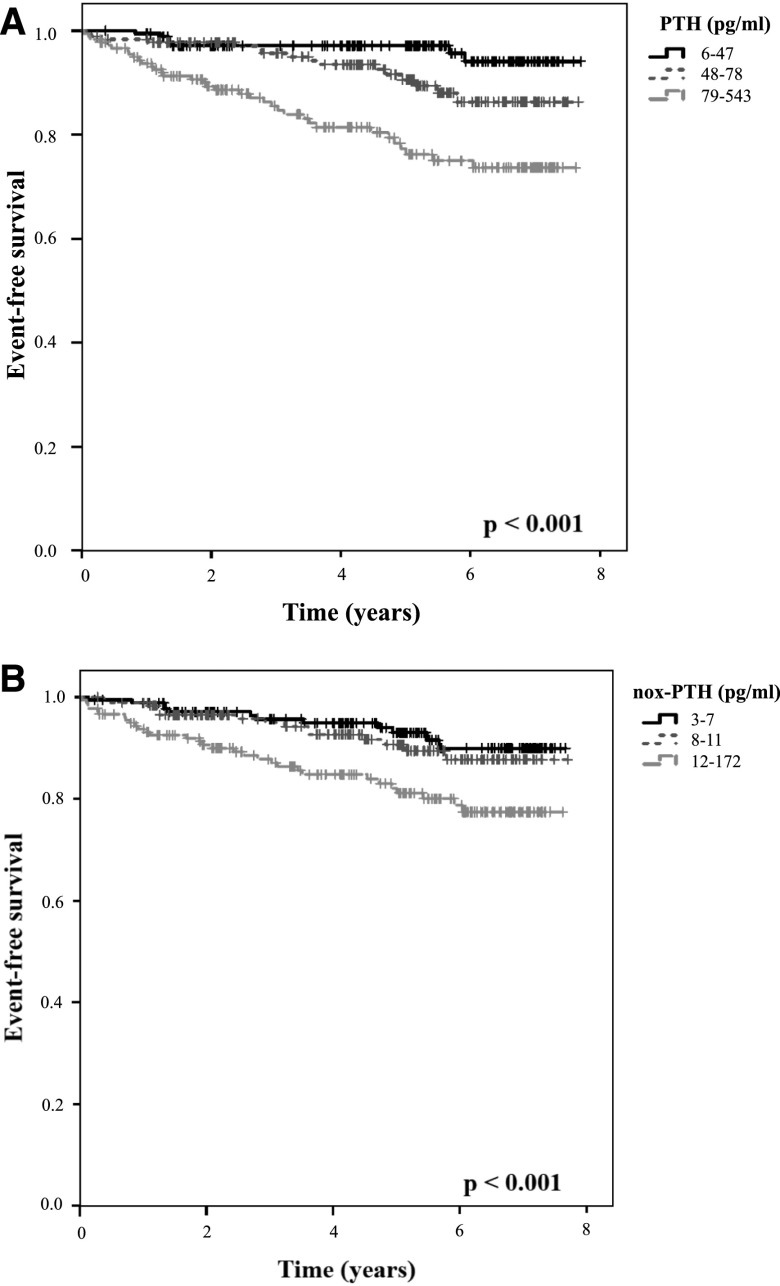

After stratifying patients by baseline PTH and nox-PTH levels into tertiles for Kaplan–Meier survival analyses, patients at highest PTH and highest nox-PTH tertiles had a significantly higher rate of atherosclerotic events (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B, respectively), acute heart failure (Figure 1, A and B, respectively), CKD progression (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B, respectively), and death from any cause (Supplemental Figure 3, A and B, respectively).

Figure 1.

Impaired event-free survival for the endpoint acute heart failure in the highest tertiles of PTH and nox-PTH. Patients were stratified into tertiles by their plasma (A) PTH and (B) nox-PTH levels, then Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank testing was performed. nox-PTH, nonoxidized parathyroid hormone; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Similarly, in unadjusted regression analysis, PTH and nox-PTH were associated with future atherosclerotic events, heart failure, CKD progression, and all-cause mortality (Tables 2–5).

Table 2.

Associations of parathyroid hormone and nonoxidized parathyroid hormone concentrations with atherosclerotic events among 535 participants in the CArdiovascular and REnal outcomes in CKD stage 2-4 patients - the Fourth HOMburg evaluation

| Variable | Person Years of FU | N Events | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjustment for Kidney Function | Adjustment for Kidney Function and Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors | Adjustment for Kidney Function, Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and CKD-Specific Risk Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 116 | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Continuous variables | ||||||||||

| Log PTH | 2255 | 116 | 4.23 (2.23 to 8.22) | <0.001 | 1.07 (0.50 to 2.26) | 0.87 | 1.00 (0.49 to 2.04) | >0.99 | 1.02 (0.48 to 2.17) | 0.96 |

| Log nox-PTH | 2255 | 116 | 3.60 (1.72 to 7.52) | 0.001 | 1.16 (0.45 to 2.98) | 0.76 | 1.16 (0.46 to 2.94) | 0.75 | 1.17 (0.47 to 2.94) | 0.74 |

| Categorized variables | ||||||||||

| PTH | ||||||||||

| First tertile (6–47 pg/ml) | 766 | 28 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Second tertile (48–78 pg/ml) | 783 | 31 | 1.01 (0.61 to 1.69) | 0.96 | 0.79 (0.47 to 1.32) | 0.36 | 0.82 (0.48 to 1.40) | 0.47 | 0.85 (0.49 to 1.46) | 0.55 |

| Third tertile (79–543 pg/ml) | 683 | 57 | 2.03 (1.29 to 3.20) | 0.002 | 0.80 (0.46 to 1.38) | 0.42 | 0.78 (0.45 to 1.35) | 0.37 | 0.76 (0.43 to 1.34) | 0.34 |

| nox-PTH | ||||||||||

| First tertile (3–7 pg/ml) | 774 | 29 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Second tertile (8–11 pg/ml) | 726 | 29 | 1.07 (0.63 to 1.80) | 0.81 | 0.78 (0.46 to 1.34) | 0.37 | 0.74 (0.43 to 1.27) | 0.27 | 0.76 (0.44 to 1.33) | 0.34 |

| Third tertile (12–172 pg/ml) | 720 | 58 | 2.12 (1.34 to 3.35) | 0.001 | 1.04 (0.62 to 1.75) | 0.86 | 0.97 (0.58 to 1.65) | 0.92 | 1.03 (0.60 to 1.78) | 0.91 |

PTH, nox-PTH, and albuminuria have been log-transformed due to skewed distribution. Log: logarithm by the base 10, thus HRs per each ten-fold increase in PTH are presented. Adjustment for “kidney function” comprises eGFR and log albuminuria. Adjustment for “kidney function and classic cardiovascular risk factors” comprises eGFR, log albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, and prevalent cardiovascular disease. Adjustment for “kidney function, classic cardiovascular risk factors, and CKD-specific risk factors” comprises eGFR, log albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, prevalent cardiovascular disease, log–C-reactive protein, plasma albumin, plasma phosphate, plasma calcium, 25-OH-vitamin D3 levels, and log FGF-23. FU, follow-up; N, number of patients with atherosclerotic events; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PTH, parathyroid hormone; nox-PTH, nonoxidized PTH.

Table 5.

Associations of parathyroid hormone and nonoxidized parathyroid hormone concentrations with death from any cause among 535 participants in the CArdiovascular and REnal outcomes in CKD stage 2-4 patients - the FOuRth HOMburg evaluation study

| Variable | Person Years of FU | N Events | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjustment for Kidney Function | Adjustment for Kidney Function and Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors | Adjustment for Kidney Function, Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and CKD-Specific Risk Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85 | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Continuous variables | ||||||||||

| Log PTH | 2518 | 85 | 6.16 (2.99 to 12.67) | <0.001 | 1.92 (0.77 to 4.78) | 0.16 | 2.15 (0.87 to 5.34) | 0.10 | 2.70 (1.01 to 7.20) | 0.05 |

| Log nox-PTH | 2518 | 85 | 3.80 (1.63 to 8.84) | 0.002 | 1.31 (0.44 to 3.90) | 0.63 | 1.41 (0.48 to 4.16) | 0.53 | 1.73 (0.56 to 5.36) | 0.34 |

| Categorized variables | ||||||||||

| PTH | ||||||||||

| First tertile (6–47 pg/ml) | 853 | 12 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Second tertile (48–78pg/ml) | 846 | 22 | 1.94 80.97 to 3.90) | 0.06 | 1.65 (0.82 to 3.36) | 0.16 | 2.07 (1.01 to 4.24) | 0.05 | 2.21 (1.06 to 4.60) | 0.03 |

| Third tertile (79–543 pg/ml) | 789 | 51 | 4.45 (2.36 to 8.40) | <0.001 | 2.35 (1.13 to 4.89) | 0.02 | 2.62 (1.27 to 5.41) | <0.01 | 2.79 (1.32 to 5.89) | <0.01 |

| nox-PTH | ||||||||||

| First tertile (3–7 pg/ml) | 851 | 18 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Second tertile (8–11 pg/ml) | 792 | 22 | 1.39 (0.75 to 2.69) | 0.30 | 1.05 (0.55 to 2.00) | 0.88 | 1.08 (0.56 to 2.05) | 0.83 | 1.22 (0.63 to 2.36) | 0.56 |

| Third tertile (12–172 pg/ml) | 834 | 45 | 2.43 (1.40 to 2.24) | 0.002 | 1.23 (0.66 to 2.31) | 0.51 | 1.17 (0.63 to 2.17) | 0.63 | 1.35 (0.70 to 2.58) | 0.37 |

PTH, nox-PTH, and albuminuria have been log-transformed due to skewed distribution. Log: logarithm by the base 10, thus HRs per each ten-fold increase in PTH are presented. Adjustment for “kidney function” comprises eGFR and log albuminuria. Adjustment for “kidney function and classic cardiovascular risk factors” comprises eGFR, log albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, and prevalent cardiovascular disease. Adjustment for “kidney function, classic cardiovascular risk factors, and CKD-specific risk factors” comprises eGFR, log albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, prevalent cardiovascular disease, log–C-reactive protein, plasma albumin, plasma phosphate, plasma calcium, 25-OH-vitamin D3 levels, and log FGF-23. FU, follow-up; N, number of deceased patients; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PTH, parathyroid hormone; nox-PTH, nonoxidized parathyroid hormone.

Table 3.

Associations of parathyroid hormone and nonoxidized parathyroid hormone concentrations with acute heart failure among 535 participants in the CArdiovascular and REnal outcomes in CKD stage 2-4 patients - The FOuRth HOMburg evaluation study for acute heart failure

| Variable | Person Years of FU | N Events | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjustment for Kidney Function | Adjustment for Kidney Function and Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors | Adjustment for Kidney Function, Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and CKD-Specific Risk Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Continuous variables | ||||||||||

| Log PTH | 2405 | 58 | 10.13 (4.40 to 23.36) | <0.001 | 2.65 (0.91 to 7.76) | 0.08 | 2.50 (0.86 to 7.29) | 0.09 | 2.25 (0.77 to 6.56) | 0.14 |

| Log nox-PTH | 2405 | 58 | 2.27 (1.64 to 11.11) | 0.003 | 0.95 (0.72 to 1.26) | 0.78 | 1.40 (0.42 to 4.70) | 0.58 | 1.40 (0.40 to 4.97) | 0.60 |

| Categorized variables | ||||||||||

| PTH | ||||||||||

| First tertile (6–47 pg/ml) | 842 | 7 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Second tertile (48–78 pg/ml) | 811 | 16 | 2.42 (1.00 to 5.88) | 0.05 | 1.87 (0.76 to 4.57) | 0.18 | 1.83 (0.74 to 4.55) | 0.19 | 1.86 (0.75 to 4.66) | 0.18 |

| Third tertile (79–543 pg/ml) | 722 | 35 | 6.14 (2.73 to 13.83) | <0.001 | 2.76 (1.11 to 6.89) | 0.03 | 2.60 (1.05 to 6.41) | 0.04 | 2.55 (1.02 to 6.37) | 0.05 |

| nox-PTH | ||||||||||

| First tertile (3–7 pg/ml) | 827 | 12 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Second tertile (8–11 pg/ml) | 770 | 15 | 1.35 (0.63 to 2.88) | 0.44 | 0.95 (0.44 to 2.06) | 0.89 | 0.91 (0.41 to 2.01) | 0.82 | 0.94 (0.42 to 2.11) | 0.88 |

| Third tertile (12–172 pg/ml) | 768 | 31 | 2.83 (1.45 to 5.50) | 0.002 | 1.24 (0.59 to 2.62) | 0.58 | 1.20 (0.57 to 2.53) | 0.63 | 1.42 (0.66 to 3.06) | 0.37 |

PTH, nox-PTH, and albuminuria have been log-transformed due to skewed distribution. Log: logarithm by the base 10, thus HRs per each ten-fold increase in PTH are presented. Adjustment for “kidney function” comprises eGFR and log albuminuria. Adjustment for “kidney function and classic cardiovascular risk factors” comprises eGFR, log albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, and prevalent cardiovascular disease. Adjustment for “kidney function, classic cardiovascular risk factors, and CKD-specific risk factors” comprises eGFR, log albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, prevalent cardiovascular disease, log–C-reactive protein, plasma albumin, plasma phosphate, plasma calcium, 25-OH-vitamin D3 levels, and log FGF-23. FU, follow-up; N, number of patients with acute heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PTH, parathyroid hormone; nox-PTH, nonoxidized parathyroid hormone.

Table 4.

Associations of parathyroid hormone and nonoxidized parathyroid hormone concentrations with CKD progression among 535 participants in the CArdiovascular and REnal outcomes in CKD stage 2-4 patients - the FOuRth HOMburg evaluation study

| Variable | Person years of FU | N Events | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjustment for Kidney Function | Adjustment for Kidney Function and Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors | Adjustment for Kidney Function, Classic Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and CKD-Specific Risk Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 73 | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Continuous variables | ||||||||||

| Log PTH | 2350 | 73 | 26.49 (12.82 to 54.75) | <0.001 | 2.67 (1.03 to 6.94) | 0.04 | 2.22 (0.83 to 5.95) | 0.11 | 2.43 (0.86 to 6.86) | 0.09 |

| Log nox-PTH | 2350 | 73 | 9.59 (4.63 to 19.87) | <0.001 | 2.55 (0.81 to 8.05) | 0.11 | 2.22 (0.66 to 7.46) | 0.20 | 2.66 (0.72 to 9.83) | 0.14 |

| Categorized variables | ||||||||||

| PTH | ||||||||||

| First tertile (6–47 pg/ml) | 841 | 11 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Second tertile (48–78 pg/ml) | 808 | 12 | 1.17 (0.52 to 2.65) | 0.71 | 0.81 (0.36 to 1.85) | 0.62 | 0.79 (0.34 to 1.86) | 0.59 | 0.78 (0.33 to 1.85) | 0.57 |

| Third tertile (79–543 pg/ml) | 670 | 50 | 5.95 (3.09 to 11.46) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.46 to 2.10) | 0.97 | 0.92 (0.42 to 2.05) | 0.84 | 1.07 (0.47 to 2.42) | 0.88 |

| nox- PTH | ||||||||||

| First tertile (3–7 pg/ml) | 829 | 13 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Second tertile (8–11 pg/ml) | 755 | 13 | 1.08 (0.49 to 2.36) | 0.85 | 0.44 (0.19 to 1.02) | 0.06 | 0.42 (0.18 to 0.99) | 0.05 | 0.52 (0.20 to 1.34) | 0.18 |

| Third tertile (12–172 pg/ml) | 725 | 47 | 4.31 (2.33 to 7.99) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.46 to 1.90) | 0.85 | 0.84 (0.40 to 1.77) | 0.64 | 1.22 (0.52 to 2.89) | 0.65 |

PTH, nox-PTH, and albuminuria have been log-transformed due to skewed distribution. Log: logarithm by the base 10, thus HRs per each ten-fold increase in PTH are presented. Adjustment for “kidney function” comprises eGFR and log albuminuria. Adjustment for “kidney function and classic cardiovascular risk factors” comprises eGFR, log albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, and prevalent cardiovascular disease. Adjustment for “kidney function, classic cardiovascular risk factors, and CKD-specific risk factors” comprises eGFR, log albuminuria, age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, prevalent cardiovascular disease, log–C-reactive protein, plasma albumin, plasma phosphate, plasma calcium, 25-OH-vitamin D3 levels, and log FGF-23. FU, follow-up; N, number of patients with CKD progression; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PTH, parathyroid hormone; nox-PTH, nonoxidized parathyroid hormone.

When adjusting for eGFR and log albuminuria, nox-PTH was no longer associated with atherosclerotic events, acute heart failure, CKD progression, or all-cause mortality. Although adjustment for eGFR and albuminuria similarly attenuated the prognostic implication of elevated PTH for future atherosclerotic events and CKD progression, PTH remained independently associated with acute heart failure and all-cause death. After further adjustment for age, sex, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, LDL cholesterol, prevalent cardiovascular disease, log-CRP, plasma albumin, plasma phosphorus, plasma calcium, 25-OH-vitamin D3 levels, and log FGF-23, patients at highest tertiles of PTH had a 2.79-fold risk for all-cause death. PTH lost its association with acute heart failure during the last adjustment step (Tables 2–5).

We performed further subgroup analyses to examine the prognostic effect of PTH and nox-PTH in patients stratified by the presence or absence of diabetes mellitus and of elevated plasma CRP, respectively. The prognostic implications of PTH and nox-PTH did neither substantially differ between patients with and without diabetes, nor between patients with and without elevated plasma CRP (Supplemental Figures 4–7).

Additionally, we assessed if the PTH/nox-PTH ratio could reveal additional prognostic information for the predefined end points. We found that the PTH/nox-PTH ratio was associated with all predefined end points in unadjusted analyses, but not associated with any predefined end point in multivariable regression analysis (Supplemental Tables 2–5).

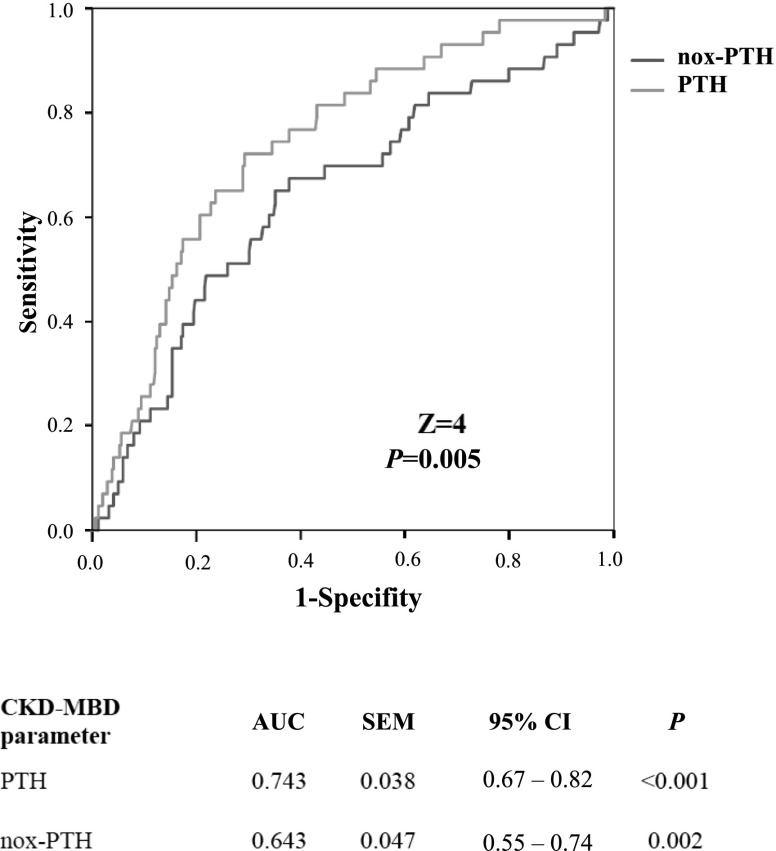

Finally, in ROC analyses we compared the discriminative power of PTH and nox-PTH for predicting the occurrence of predefined events within the first 4 years of follow-up. Areas under the curve were significantly higher for PTH than for nox-PTH for the end points of acute heart failure (Figure 2, Z=4, P<0.001), CKD progression (Supplemental Figure 8; Z=4, P<0.001), and all-cause death (Supplemental Figure 9; Z=2, P=0.04). For the end point of atherosclerotic events, there was no significant difference between the AUCs of PTH and nox-PTH (Supplemental Figure 10; Z=7, P=0.50).

Figure 2.

In Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves analyses PTH was superior to nox-PTH in the prediction of acute heart failure with the first 4 years of follow-up. Correlated ROC curves were compared by the Delong test for significance. AUC, area under the curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CKD-MBD, CKD–mineral and bone disorder; nox-PTH, nonoxidized parathyroid hormone; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Discussion

Against the background of experimental data on the nonfunctionality of ox-PTH (14,15), it has been hypothesized that novel PTH assays that specifically measure nox-PTH may be more informative in clinical practice than conventional second- or third-generation assays, because these assays only measure biologically active PTH, but not inactive ox-PTH. If this hypothesis holds true, nox-PTH measurements should be more closely associated with other components of CKD-MBD and cardiovascular and kidney outcome than conventional PTH measurements. The only study so far that investigated the prognostic effect of nox-PTH among patients with CKD in a prospective study design was published by Tepel et al. (16). Among 340 patients receiving hemodialysis, study participants with nox-PTH levels in the highest tertile had significantly longer survival than patients within low and intermediate nox-PTH tertiles, whereas PTH—as measured with a third-generation assay—had a U-shaped association with survival. Subgroup analyses suggest that the prognostic implication of high nox-PTH may be restricted to patients with low third-generation assay PTH measurements, whereas nox-PTH did not independently inform on patient outcome if third-generation PTH measurements were intermediate or high.

However, it remains uncertain how far these results may be transferred to patients with CKD not receiving dialysis. Against this background, we compared the prognostic effect of nox-PTH measurements with conventionally measured PTH levels in our CARE FOR HOMe cohort, which comprises 535 patients with CKD with an eGFR range between 89 and 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 followed for a median of 5.1 years. We found that nox-PTH was not more closely associated with patient survival than PTH.

The discrepant results between the study by Tepel et al. (16) and our CARE FOR HOMe study might be explained by a higher exposure of patients receiving dialysis to oxidative stress and a higher proportion of oxidized PTH, compared with patients with CKD not receiving dialysis. Thus, the specific measurement of nox-PTH may yield a higher diagnostic gain and therefore allow better information on patient outcome than traditional PTH measurements. Interestingly, the range of nox-PTH levels in our cohort is very similar to the range of nox-PTH levels in the Tepel et al. study (CARE FOR HOMe: 9 [IQR, 7–13] pg/ml; Tepel et al.: 6 [IQR, 2–14 ng/L]), even though nox-PTH was measured with second-generation assays in our study, and with third-generation assays in the study by Tepel et al.

Whereas Tepel et al. (16) focused upon all-cause mortality, CARE FOR HOMe additionally provides the first data on the prognostic implications of nox-PTH for kidney and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CKD not receiving dialysis. After adjustment for potential confounders, nox-PTH was not associated with any predefined end point in multivariable regression analyses. In contrast, conventional second-generation PTH measurements remained independently associated with all-cause death. In ROC analyses, second-generation PTH measurements outperformed nox-PTH measurements in prediction of progression of CKD, acute heart failure, and all-cause mortality.

Interestingly, neither nox-PTH nor PTH levels were correlated with atherosclerotic events. Our results are in line with findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study, which investigated 2312 older individuals from the general United States population, most of whom had intact kidney function: During a follow up period of 14 years, PTH was only associated with acute heart failure, and not with cardiovascular death or myocardial infarction (23). Admittedly, other cohort studies reported disparate findings, with some—but not all—studies reporting a significant association between PTH and future atherosclerotic events (24). We cannot confirm the close relationship between increased PTH levels and acute heart failure reported by other studies (10,23), because the association between PTH and acute heart failure lost significance after full adjustment in our study.

In line with the findings from CARE FOR HOMe, various other studies described an association between increased PTH with mortality in patients with CKD (8,9), and lag-censored post hoc analyses from EVOLVE reported lower mortality among patients receiving dialysis on cinacalcet treatment than on placebo (10).

Strengths of CARE FOR HOMe are the long follow-up period of >5 years with no patients lost to follow-up. Each cardiovascular and kidney event was verified by reviewing medical records by the two physicians who were blinded to the results from laboratory measurements. A potential limitation is the issue that PTH is a central regulator of calcium-phosphate metabolism, thus interacting with other CKD-MBD components. Even though we performed multivariable Cox analyses and included relevant CKD-MBD parameters such as FGF-23, 25-OH-vitamin D3, plasma calcium, and plasma phosphorus, we cannot exclude residual confounding by unmeasured CKD-MBD mediators. As a further limitation, we did not measure oxidized PTH directly. Because conventional PTH assays measure both oxidized PTH and nox-PTH, and because levels of PTH surpass nox-PTH measurements by an order of magnitude, the majority of circulating PTH may be oxidized. As a consequence, total PTH is more strongly correlated with oxidized PTH than with nox-PTH (18). Some authors therefore postulate that total PTH assays reflect oxidative stress rather than biologic PTH activity, referring to epidemiologic studies in which ox-PTH was estimated by subtracting ox-PTH from total PTH (18). However, this estimation has never been validated by direct measurements of ox-PTH, and these findings have to be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, second-generation PTH measurements were more closely associated with cardiovascular events, CKD progression, and mortality than nox-PTH measurements in our cohort of patients with CKD not receiving dialysis. Implementation of nox-PTH measurement into clinical routine for non–dialysis-dependent patients with CKD is of questionable value at this time, and the application of various PTH assays in clinical practice may confuse rather than inform the busy clinician. Thus, we advocate using second- and third-generation PTH assays as the methods of choice to determine PTH in non–dialysis-dependent patients with CKD.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Martina Wagner and Marie-Theres Blinn for their excellent assistance. Furthermore, we thank all of the study participants of CArdiovascular and REnal outcomes in CKD stage 2-4 patients - the FOuRth HOMburg evaluation.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Clear the Fog around Parathyroid Hormone Assays: What Do iPTH Assays Really Measure?,” on pages 524–526.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.06620617/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Foley RN, Parfrey PS: Cardiovascular disease and mortality in ESRD. J Nephrol 11: 239–245, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, Kent GM, O’Dea R, Murray DC, Barre PE: Mode of dialysis therapy and mortality in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 267–276, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jager DJ, Grootendorst DC, Jager KJ, van Dijk PC, Tomas LM, Ansell D, Collart F, Finne P, Heaf JG, De Meester J, Wetzels JF, Rosendaal FR, Dekker FW: Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality among patients starting dialysis. JAMA 302: 1782–1789, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzog CA, Asinger RW, Berger AK, Charytan DM, Díez J, Hart RG, Eckardt KU, Kasiske BL, McCullough PA, Passman RS, DeLoach SS, Pun PH, Ritz E: Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. A clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 80: 572–586, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ketteler M, Block GA, Evenepoel P, Fukagawa M, Herzog CA, McCann L, Moe SM, Shroff R, Tonelli MA, Toussaint ND, Vervloet MG, Leonard MB: Executive summary of the 2017 KDIGO Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) guideline update: What’s changed and why it matters. Kidney Int 92: 26–36, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, Smulders M, Tian J, Williams LA, Andress DL: Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: Results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int 71: 31–38, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham J, Locatelli F, Rodriguez M: Secondary hyperparathyroidism: Pathogenesis, disease progression, and therapeutic options. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 913–921, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wald R, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Cheung AK, Levey AS, Eknoyan G, Miskulin DC: Disordered mineral metabolism in hemodialysis patients: An analysis of cumulative effects in the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 531–540, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tentori F, Blayney MJ, Albert JM, Gillespie BW, Kerr PG, Bommer J, Young EW, Akizawa T, Akiba T, Pisoni RL, Robinson BM, Port FK: Mortality risk for dialysis patients with different levels of serum calcium, phosphorus, and PTH: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis 52: 519–530, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chertow GM, Block GA, Correa-Rotter R, Drüeke TB, Floege J, Goodman WG, Herzog CA, Kubo Y, London GM, Mahaffey KW, Mix TC, Moe SM, Trotman ML, Wheeler DC, Parfrey PS; EVOLVE Trial Investigators : Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 367: 2482–2494, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skugor M, Gupta M, Navaneethan SD: Evolution and current state of assays for measuring parathyroid hormone. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 20: 221–228, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Himmelfarb J, Stenvinkel P, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM: The elephant in uremia: Oxidant stress as a unifying concept of cardiovascular disease in uremia. Kidney Int 62: 1524–1538, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Locatelli F, Canaud B, Eckardt KU, Stenvinkel P, Wanner C, Zoccali C: Oxidative stress in end-stage renal disease: An emerging threat to patient outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1272–1280, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zull JE, Smith SK, Wiltshire R: Effect of methionine oxidation and deletion of amino-terminal residues on the conformation of parathyroid hormone. Circular dichroism studies. J Biol Chem 265: 5671–5676, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horiuchi N: Effects of oxidation of human parathyroid hormone on its biological activity in continuously infused, thyroparathyroidectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res 3: 353–358, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tepel M, Armbruster FP, Grön HJ, Scholze A, Reichetzeder C, Roth HJ, Hocher B: Nonoxidized, biologically active parathyroid hormone determines mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98: 4744–4751, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hocher B, Armbruster FP, Stoeva S, Reichetzeder C, Grön HJ, Lieker I, Khadzhynov D, Slowinski T, Roth HJ: Measuring parathyroid hormone (PTH) in patients with oxidative stress--do we need a fourth generation parathyroid hormone assay? PLoS One 7: e40242, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hocher B, Yin L: Why current PTH assays mislead clinical decision making in patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Nephron 136: 137–142, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seiler S, Rogacev KS, Roth HJ, Shafein P, Emrich I, Neuhaus S, Floege J, Fliser D, Heine GH: Associations of FGF-23 and sKlotho with cardiovascular outcomes among patients with CKD stages 2-4. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1049–1058, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seiler S, Wen M, Roth HJ, Fehrenz M, Flügge F, Herath E, Weihrauch A, Fliser D, Heine GH: Plasma Klotho is not related to kidney function and does not predict adverse outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 83: 121–128, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction; Authors/Task Force Members Chairpersons, Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD; Biomarker Subcommittee, Jaffe AS, Katus HA, Apple FS, Lindahl B, Morrow DA; ECG Subcommittee, Chaitman BR, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H; Imaging Subcommittee, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow JJ, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ; Classification Subcommittee, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW; Intervention Subcommittee, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasche P, Ravkilde J; Trials & Registries Subcommittee, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML; Trials & Registries Subcommittee, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G; Trials & Registries Subcommittee, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D; Trials & Registries Subcommittee, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG), Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck-Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S; Document Reviewers, Morais J, Aguiar C, Almahmeed W, Arnar DO, Barili F, Bloch KD, Bolger AF, Botker HE, Bozkurt B, Bugiardini R, Cannon C, de Lemos J, Eberli FR, Escobar E, Hlatky M, James S, Kern KB, Moliterno DJ, Mueller C, Neskovic AN, Pieske BM, Schulman SP, Storey RF, Taubert KA, Vranckx P, Wagner DR: Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 1581–1598, 2012. 22958960 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palm F, Urbanek C, Rose S, Buggle F, Bode B, Hennerici MG, Schmieder K, Inselmann G, Reiter R, Fleischer R, Piplack KO, Safer A, Becher H, Grau AJ: Stroke incidence and survival in Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany: The Ludwigshafen Stroke Study (LuSSt). Stroke 41: 1865–1870, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kestenbaum B, Katz R, de Boer I, Hoofnagle A, Sarnak MJ, Shlipak MG, Jenny NS, Siscovick DS: Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and cardiovascular events among older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 1433–1441, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Ballegooijen AJ, Reinders I, Visser M, Brouwer IA: Parathyroid hormone and cardiovascular disease events: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am Heart J 165: 655–664, 664.e651–655, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.