Abstract

Aim

Previous research has indicated an association between diabetes and anxiety. However, no synthesis has determined the direction of this association. The aim of this study was to determine the longitudinal relationship between anxiety and diabetes.

Methods

We searched seven databases for studies examining the longitudinal relationship between anxiety and diabetes. Two independent reviewers screened studies from a population aged 16 or older that examined either anxiety as a risk factor for incident diabetes or diabetes as a risk factor for incident anxiety. Studies that met eligibility criteria were put forward for data extraction and meta‐analysis.

Results

In total 14 studies (n = 1 760 800) that examined anxiety as a risk factor for incident diabetes and two (n = 88 109) that examined diabetes as a risk factor for incident anxiety were eligible for inclusion in the review. Only studies examining anxiety as a risk factor for incident diabetes were put forward for the meta‐analysis. The least adjusted (unadjusted or adjusted for age only) estimate indicated a significant association between baseline anxiety with incident diabetes (odds ratio 1.47, 1.23–1.75). Furthermore, most‐adjusted analyses indicated a significant association between baseline anxiety and incident diabetes. Included studies that examined diabetes to incident anxiety found no association.

Conclusions

There was an association between baseline anxiety and incident diabetes. The results also indicate the need for more research to examine the direction of association from diabetes to incident anxiety. This work adds to the growing body of evidence that poor mental health increases the risk of developing diabetes.

What's new?

This is the first synthesis to determine the direction of association between anxiety and diabetes.

The results indicate that anxiety is a risk factor for incident diabetes.

The results also indicate that there is a need for further research into diabetes as a risk factor for incident anxiety.

What's new?

This is the first synthesis to determine the direction of association between anxiety and diabetes.

The results indicate that anxiety is a risk factor for incident diabetes.

The results also indicate that there is a need for further research into diabetes as a risk factor for incident anxiety.

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes is increasing, with current estimates projecting that 642 million people worldwide will have diabetes by 2040 1. As the prevalence of diabetes increases there is interest in identifying modifiable diabetes risk factors that could be targeted by interventions to reduce this projected increase. Alongside this, there is also interest in reducing the burden of diabetes in people who already have the condition by identifying modifiable risk factors associated with poorer health outcomes. Poor mental health has been identified as a potentially modifiable risk factor associated with an increased risk of both developing diabetes and poorer outcomes in people who have diabetes 2, 3. Therefore, there is interest in how mental illness and diabetes are linked.

Anxiety disorders are a group of mental disorders characterized by feelings of anxiety and fear that significantly impact the social and occupational functioning of individuals 4. They are among some of the most prevalent mental disorders in the population, affecting up to 30% of adults 5, 6. Furthermore, anxiety disorders are one of the leading causes of disability worldwide 7 and are associated with a poorer quality of life 8. Alongside their immediate impact on mental health and functioning, there is also evidence that symptoms of anxiety and anxiety disorders might be associated with an increased risk of developing non‐communicable diseases such as heart disease 9. It is possible that anxiety could lead to diabetes as it shares strong associations with many of the acknowledged risk factors for diabetes such as overweight/obesity 10, cardiometabolic abnormalities 11, unhealthy lifestyle behaviours 12 and sleep disturbance 13. However, data on anxiety as a risk factor for incident diabetes has not yet been synthesized, so it is unclear whether anxiety itself is an independent risk factor for the development of diabetes.

Previous research indicates that people with diabetes have a greater likelihood of developing mental health problems such as depression 14. It is possible that biological changes induced by diabetes 15 alongside lifestyle limitations and feelings related to living with a serious chronic illness 16 could all be linked with poorer mental health. However, there is no synthesis that tells us whether diabetes might be linked with a greater risk of developing anxiety. Previous meta‐analyses and systematic reviews indicate that people with diabetes have an increased likelihood of concurrent anxiety 17, 18, however we do not know if diabetes is associated with an increased risk of developing incident anxiety.

The aim of this review was to determine the longitudinal association between diabetes and anxiety by systematically searching for and reviewing studies that investigated either anxiety as a risk factor for incident diabetes in adults aged 16 or older or diabetes as a risk factor for incident anxiety in adults aged 16 or older.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted by KS and SD between January 2017 and August 2017. The study protocol was registered on PROSPERO (protocol ID: CRD42017056775; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO). There were no restrictions on publication date or language, although only English and French language studies were reviewed. Search terms relating to synonyms of ‘anxiety’ and ‘diabetes’ (see Doc. S1) were searched in seven databases including PubMed (United States National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), SCOPUS (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands), EMBASE (Elsevier), ISI Web of Knowledge (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA), PsychINFO (American Psychological Association, Washington DC, USA), CINAHL (Elsevier) and ProQuest (Dissertations and Theses; conference papers index and Nursing and Allied Health) (ProQuest, Ann Arbour, MI, USA).

Further to this, hand searches were undertaken within relevant conference proceedings and journals (see Supporting Information Doc. S1). The bibliographies of relevant reviews on anxiety and diabetes 17, 18, 19 were also searched.

Study selection

For the direction of anxiety to incident diabetes, eligible studies were prospective studies that assessed the incidence of diabetes in people aged 16 or over who were assessed for the presence of anxiety at baseline. To examine diabetes to incident anxiety, studies were required to be prospective studies that assessed the incidence of anxiety in people aged 16 or over who were assessed for the presence of diabetes at baseline. Only studies that examined Type 1 and/or Type 2 diabetes were included. Included studies were required to assess anxiety symptoms (as defined by elevated anxiety symptoms on a validated scale) or anxiety disorders (as assessed by diagnostic interview or clinical diagnosis). In this review, anxiety was defined as the anxiety disorders included in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) version IV or V; version V excludes post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) whereas version IV includes these disorders. For both research questions, exclusion criteria included a cross‐sectional study design, studies that did not assess incidence (i.e. did not control for baseline levels of the outcome) and those that explicitly assessed gestational diabetes. There were no restrictions set on the type of population included.

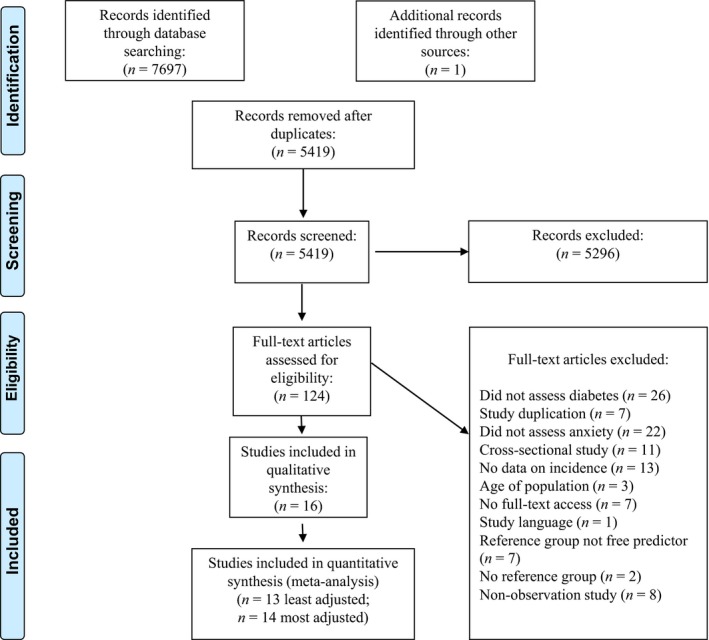

Two authors (KS and SD) independently screened all studies for these criteria (see Fig. 1), and disagreements were resolved by consensus or, where necessary, a third author (NS). Studies that were shortlisted after full‐text assessment were put forward for data extraction and quality assessment.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram: study selection

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction and quality assessment were completed independently by two authors (KS and SD) with disagreements resolved by consensus. The following characteristics were extracted from eligible studies: author (date), study characteristics (name, country, number of participants), sample characteristics (% female, ethnicity and age), anxiety measurement (name of measure, information regarding type of anxiety assessed), diabetes measurement, outcome information (follow‐up length, % developed outcome), statistical analysis (type of statistical test and confounders controlled for) and measures of association (unadjusted and/or most‐adjusted estimate).

Quality assessment was performed using two tools: the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) 20 and the Risk Of Bias In Non‐randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS‐I) 21. We opted to use both tools because the NOS offers a good overview of study methodology and representativeness, whereas the ROBINS‐I offers a more comprehensive assessment of bias. The following characteristics were assessed using the NOS: representativeness of sample (community sample), selection of controls (same population as sample), measure of predictor and outcome (validated measurements), demonstration that outcome not present at start of study, length of follow‐up (≥ 5 years), adequacy of follow‐up participation rate (> 60%), inclusion of at least three important confounders and if the study controlled for the most important confounder (metabolic abnormalities). Studies were assessed on a star system whereby they were given one star for each criterion met. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 9, with higher scores being indicative of better study quality. See Table S1 for NOS quality assessment.

Use of the ROBINS‐I requires pre‐identification of the most important confounders to assess bias. For the present review assessing the direction of anxiety to diabetes, the most important confounders were determined to be sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, sex, ethnicity, education, income) and cardiometabolic abnormalities (e.g. adiposity, blood pressure, inflammation, cholesterol, triglycerides). For the direction of diabetes to anxiety, the most important confounders were determined to be sociodemographic characteristics and other chronic conditions. Choice of confounders was based on these variables sharing a potentially explanatory association between the relevant predictor and outcome 10, 11, 18. The ROBINS‐I assessed studies on the following characteristics: bias due to confounding, bias in selection of participants into study, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in measurement of outcomes and bias in selection of the reported result. Following the assessment of bias in each domain the authors independently judged the overall risk of bias as: critical, serious, moderate or low. See Table S2 for the ROBINS‐I quality assessment.

In addition to the quantitative quality assessments, both screening authors also undertook a qualitative quality assessment to independently determine the main strengths and limitations of each included study.

Meta‐analysis

Eligible data were entered into a random‐effects meta‐analysis because this provides more conservative estimates allowing for more heterogeneity between studies. If studies provided stratified analyses for their predictor (e.g. analyses stratified by gender) these were first combined into a single estimate. We then plotted the least adjusted (unadjusted or adjusted for age only) association, followed by the most adjusted. For the least adjusted association, we either used odds ratios (ORs; unadjusted or adjusted for age only) or calculated the OR using raw event data. For each association, we performed a series of sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of methodological study differences (e.g. population studied, confounders controlled for, anxiety assessment) on the strength of the associations.

Alongside the meta‐analyses we determined statistical heterogeneity for each analysis by calculating the inconsistency (I 2) index (scores of 25%, 50% and 75% indicate low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively). Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger's test, with symmetric funnel plots and a non‐significant Egger's test being indicative of no publication bias. All analyses were performed with Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis 3.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA).

Results

Study selection

In total, 5418 studies were found after excluding duplicates (Fig. 1). After applying broad screening criteria, 5295 studies were excluded. The main reasons for excluding studies were that they did not assess the predictor or outcome of interest, the study was conducted in a non‐human population, language restrictions or that the study was cross‐sectional. A total of 124 studies were put forward for full‐text analysis, following which 108 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were that the study did not assess incidence of diabetes or anxiety, the study was a poster presentation with no full‐text access for data extraction, the study was cross‐sectional and the study did not perform the analysis required for inclusion in this review. Inter‐rater reliability for study screening was good (kappa = 0.72).

Of the remaining 16 studies, 14 examined the direction of association from anxiety to incident diabetes and two examined the direction of association from diabetes to incident anxiety. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the studies. Table 2 summarizes the quality assessments performed for all studies along with a qualitative synthesis of the main study strengths and weaknesses as identified by the reviewers (for the full quality assessment tables see Tables S1 and S2). Most studies (n = 11) were from North America 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, with an additional three studies from Europe 33, 34, 35, one from Asia 36 and one from the Middle‐East 37.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author, year; country | Study | Baseline sample | Anxiety measurement | Diabetes incidence Measurement | Incident diabetes cases | Statistical analysis | Confounders adjusted | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure (cut‐off points) | Type of anxiety (length episode) | Sociodemographics | Cardiometabolic and/or adiposity | Other | Least adjusted | Most adjusted | ||||||

| Anxiety to incident diabetes | ||||||||||||

| Abraham et al., 2015 22; USA |

The Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) N = 5566 |

Age: 45–85 years (mean 61.6 years) Sex: 53.2% female Ethnicity: 38% white, 28% African American, 23% Hispanic, 11% Chinese |

Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale. (Quartiles Q1 < 13; Q2 = 13–15; Q3 = 16–19; Q4 = 20–40) |

Trait anxiety (current) | Fasting glucose ≥ mmol/l (126 mg/dl), use of oral hypoglycaemic medication and/or insulin, or self‐reported physician diagnosis |

695 (12.4%) Follow‐up: 11.4 years |

Cox proportional hazards regression (reference group: Q1) | Sex, age, race/ethnicity, years of education, annual income | Waist circumference, blood pressure, C‐reactive protein. | Depressive symptoms, antidepressants, diet, smoking, alcohol use, interleukin‐6 |

Q2: HR 1.02 (0.83–1.26) Q3: HR 0.99 (0.80–1.23) Q4: HR 1.16 (0.93–1.45) |

Q2: HR 0.98 (0.78–1.23) Q3: HR 0.99 (0.78–1.26) Q4: HR 1.16 (0.87–1.54) |

| Atlantis et al, 2013 33; The Netherlands |

Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) N = 2460 |

Age: 18–65 years (mean 42) Sex: 66% female Ethnicity: not specified |

(A) 21‐item Beck Anxiety Inventory (B) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) |

(A) Anxiety symptom severity (past month) (B) Anxiety disorder: Social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and/or agoraphobia (6‐month) |

Self‐report for lifetime diagnosis, anti‐diabetic medication use, or fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/l |

25 incident diabetes cases (1.3%) Follow‐up: 2 years |

Logistic regression (predictor= every 10‐point increase BAI) | – | – | – | OR 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | – |

| Boyko et al, 2010 23; USA |

Millennium Cohort Study N = 44 754 |

Age: 18–68 years (median 36 years) No incident diabetes Sex: 26.4% female Ethnicity: 71.8% Caucasian 11.6% African American 5.8% Hispanic 8.6% Asian 2.2% other Incident diabetes Sex: 27.7% female Ethnicity: 65.2% Caucasian 18.9% African American 6.3% Hispanic 7.4% Asian 2.2% other |

PTSD: 17‐item PCL‐C (moderate or higher level one intrusion symptom, three avoidance symptoms, and two hyperarousal symptoms) Panic: PHQ (endorsed eight items asking about whether had panic attacks and cognitions about panic attack) Other anxiety: PHQ (endorsed item, asking about feeling nervous, anxious, on edge, and at least three of six additional anxiety symptoms) |

PTSD symptoms (past month) Panic disorder symptoms (2 weeks) Other anxiety symptoms (2 weeks) |

Self‐report |

376 incident diabetes cases (0.01%) Follow‐up: 3 years |

Logistic regression | Age, sex, ethnicity, educational attainment | BMI | – |

PTSD

OR 2.56 (1.78–3.67) Panic disorder OR 3.19 (1.78–5.71) Other anxiety OR 2.03 (1.16–3.54) |

PTSD

OR 2.24 (1.54–3.26) Panic disorder: OR 2.88 (1.58–5.24) Other anxiety OR 1.77 (1.00–3.13) |

| Chien & Lin, 2016 36; Taiwan |

Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) program N = 766 427 |

Age: 18 + years (mean not specified) Anxiety group Sex: 11.88% female Control group Sex: 5.77% female |

ICD‐9‐CM diagnostic codes (at least two service claims during 2005 for either outpatient or inpatient care) | Anxiety states, panic disorder, generalize anxiety disorder, phobic disorder, obsessive‐compulsive disorder, acute stress disorder, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (past year) | At least one prescription (oral hypoglycaemic agents or insulin) for treatment of diabetes |

37 032 incident cases Follow‐up: 5 years |

Cox regression model | Age, sex, insurance amount, region, and urbanicity | – | – | – | RR 1.34 (1.28–1.41) |

| Demmer et al., 2015 24; USA |

First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) and its epidemiological follow‐up study (NHEFS) N = 3233 |

Age: 25–74 years (mean 49 ± 14 years) Sex: 2% female Ethnicity: 86% white 14% African American |

General Wellbeing Scale: Anxiety subscale (GWB‐A): high (0–12), moderate (13–18), low (19–25) | Anxiety symptoms (past month) |

(A) Death certificate ICD‐9 code specifies diabetes (B) Self‐reported physician diagnosis requiring medication (C) Healthcare facility stay with diabetes discharge diagnosis. |

298 incident cases (9.2%) Follow‐up: 17 years |

(A) Multivariable adjusted risk ratios from fitted logistic regression models | Age, race, education, | BMI | Smoking status, and physical activity |

Moderate anxiety

Women: RR 1.33 (0.73–2.40) Men: RR 0.89 (0.57–1.38) High anxiety Women: RR 2.15 (1.24–3.74) Men: RR 0.68 (0.32–1.42) |

Moderate anxiety

Women: RR 1.42 (0.78–2.61) Men: RR 0.94 (0.61–1.44) High anxiety Women: RR 1.72 (0.86–3.44) Men: RR 0.70 (0.32–1.55) |

| Deschênes et al., 2016 25; Canada |

Emotional Well‐being, Metabolic Factors and Health Status (EMHS) study N = 2486 |

Age: 40–69 years Sex: 57.4% female Ethnicity: 93.3% white 6.7% non‐white |

Generalized anxiety disorder questionnaire – 7‐item (≥ 10 high anxiety) | Generalized anxiety symptoms (2 weeks) | Self‐report |

86 incident cases (3.5%) Follow‐up: 4.6 years |

Logistic regression | Age, sex, ethnicity, education, marital status | Central obesity, hypertension, triglycerides, HDL‐cholesterol | IPAQ score (physical activity), smoking status, antidepressant use |

High anxiety no prediabetes

OR 0.92 (0.21–4.04) High anxiety prediabetes OR 10.95 (5.24–22.90) |

High anxiety no prediabetes

OR 1.13 (0.25–5.10) High anxiety prediabetes OR 8.95 (3.54–22.63) |

| Edwards and Mezuk., 2012 26; USA |

Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study N = 1446 |

Age: 30+ years Sex: 68.5% female Ethnicity: 63% white 33% black |

Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) | Anxiety disorders:generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, and agora‐phobia | Self‐report |

85 incident cases (4.4%) Follow‐up: 11 years |

Logistic regression | Age, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status | BMI |

Tobacco use, physical activity, alcohol use, and sleeping habits Major depressive disorder |

OR 1.21 (0.72–2.03) | OR 1.00 (0.53–1.89) |

| Farvid et al., 2014 27; USA |

Nurses' Health Study (NHS) N = 69 336 Nurses' Health Study II (NHS II) N = 80 120 Health Professional's Follow‐Up Study (HPFS) N = 30 830 |

NHS

Age 30–55 years, Sex: 100% female NHS II Age 24–43 years Sex: 100% female HPFS Age 40–75 years Sex: 0% female Ethnicity all studies: ~ 98% white |

(A) Crown‐Crisp index (CCI) (Continuous) (B) CCI ≥ 6 vs. ≤ 2 |

Phobic anxiety (current) |

Questionnaire: (A) One or more classic symptom (excessive thirst, polyuria, weight loss, hunger) plus fasting plasma glucose ≥ 140 mg/dl or random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl (B) ≥ 2 elevated plasma glucose concentrations on different occasions (fasting concentrations ≥ 140 mg/dl, random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl and/or concentrations glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl after 2‐h OGTT. N.B. For cases diagnosed on/after 1998 fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl. |

NHS

6180 incident cases Follow‐up: 20 years NHS II 4401 incident cases Follow‐up: 18 years HPFS 2295 incident cases Follow‐up: 20 years N.B.: For HPFS incident cases reported as 2304, but according to table it is 2295 |

Cox proportional hazards models | Age, race, marital status, husband education (in NHS and NHS II). | BMI | Family history of diabetes, current aspirin use, menopausal status and hormone use (in NHS and NHS II), smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, energy intake, dietary score, coffee |

(A) NHS HR 1.06 (1.05–1.07) NHS II HR 1.11 (1.09–1.12) HPFS HR 1.04 (1.02–1.06) (B) NHS HR 1.06 (1.05–1.07) NHS II HR 1.11 (1.09–1.12) HPFS HR 1.04 (1.02–1.06) N.B. age adjusted |

(A) NHS HR 1.03 (1.02–1.04) NHS II HR 1.04 (1.03–1.05) HPFS HR 0.99 (0.97–1.01) (B) NHS HR 1.13 (1.05–1.22) NHS II HR 1.29 (1.18–1.42) HPFS HR 0.90 (0.75–1.01) |

| Khambaty et al., 2017 28; USA |

Improving Mood‐Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) trial N = 2156 |

Age: 60 + years (mean 69.0 ± 7.3 years) Sex: 68.9% female Ethnicity: 53.3% African American |

PHQ‐2 (nerves or feeling anxious or on edge, worrying about a lot of different things). Anxiety: endorsed both screening items. |

Anxiety symptoms (past month) | Medical records and insurance database: (ICD‐9 code 250), fasting glucose of ≥ 126 mg/dl, HbA1c of ≥ 8.0%, prescription for insulin or oral hypoglycaemic medication, or death due to diabetes mellitus (ICD‐10 codes E10‐E14 as first‐listed cause of death). |

558 incident cases (25.9%) Follow‐up: 10 years |

Cox proportional hazards models | Age, sex, race | BMI, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia | Smoking. | – |

Anxiety (either item)

HR 1.36 (1.15–1.61) Feeling anxious item HR 1.26 (1.06–1.51) Worry item HR 1.28 (1.07–1.52) |

| Miller‐Archie et al., 2014 30; USA |

The World Trade Center Health Registry N = 36 899 |

Age: 18+ years With incident diabetes Sex: 34.6% female Without incident diabetes Sex: 38.4% female |

9/11‐specific PTSD Checklist (PCL), (PTSD ≥ 44) | PTSD symptoms (past month) | Self‐report |

2143 incident cases (5.8%) Follow‐up: 9 years |

Logistic regression | Sex, age, race/ethnicity, education | Hypertension, high cholesterol, BMI | – | OR 1.73 (1.56–1.93) | OR 1.28 (1.14–1.44) |

| Pérez‐Piñar et al., 2016 35; UK |

All patients, aged ≥30 years, registered in 140 primary care practices in London N = 524 952 |

Age: 30+ years (mean 45.9 ± 13.9 years) Sex: 47.1% female Ethnicity: 41.9% white 27.6% South Asian 17.0% black 6.2% other 7.3% unknown |

Anxiety Read codes | Anxiety: Anxiety states, phobic disorders, other anxiety disorders, phobic anxiety disorders, generalized anxiety) | Diabetes read codes |

31 942 incident cases (6.3%) Follow‐up: 10 years |

Cox regression models, hazard ratios | Age, gender, ethnicity, and social deprivation | – | Antidepressants, antipsychotics | – | HR 1.14 (1.08, 1.20) |

| Scherrer et al., 2011 31; USA |

National VA Administrative Data N = 184 925 |

Age: 25‐80 years (mean 55.6 ± 13.1 years) Sex: 9.6% female Ethnicity: 75.5% white 20% non‐white 4.5% unknown |

ICD‐9 codes |

PTSD GAD Panic Other anxiety |

Diabetes assessed by ICD‐9‐CM code |

28 535 incident cases (15.4%) Follow‐up: 6 years |

(A) Cox proportional hazard models (B) Number of events |

Age | BMI (PTSD) | PTSD (GAD) |

PTSD

HR 1.25 (1.21–1.29) GAD HR 1.07 (1.01–1.13) |

PTSD

HR 1.25 (1.21–1.29) GAD HR 1.09 (1.06–1.12) |

| Shirom et al., 2010 37; Israel |

Clarlit health services database N = 870 |

Age: 18–73 years (mean 41.70 years) Sex: 33% female |

Cornell Medical Index: Unclear how this was scored but most likely continuous (0–5) |

Anxiety symptoms (how they feel most of the time) | ICD‐9 codes cross‐validated against medication use files and serum analysis of HbA1c for the diagnosis of diabetes |

109 incident cases (12.5%) Follow‐up: 20 years |

Cox proportional hazards regression |

Age, sex, educational level |

BMI, cholesterol, triglycerides, arterial blood pressure, glucose | Smoking, exercise, alcohol consumption, vigour, depressive symptoms | – | HR 1.00 0.78–1.26 |

| Vaccarino et al., 2014 32; USA |

Vietnam Era Twin Registry N = 4340 |

Age: 18+ years Sex: 0% female Ethnicity: 90.1% white |

Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) Subthreshold PTSD was defined by meeting some, but not all, criteria for PTSD |

PTSD (lifetime) | Self‐reported (doctor diagnosis and medication) |

658 incident cases (15.2%) Follow‐up: median 19.4 years |

Multivariate logistic regression | Age, race, ethnicity, marital status, education | BMI, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia | Branch of service, enlistment year, service in Southeast Asia, and military rank at enlistment, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, history of cardiovascular disease, depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and alcohol or drug abuse disorder |

Subthreshold PTSD

OR 1.2 (0.8–1.7) PTSD OR 1.0 (0.6–1.7) N.B. adjusted for age |

Subthreshold PTSD

OR 1.2 (0.9–1.5) PTSD OR 1.2 (0.9–1.7) |

| Diabetes to incident anxiety | ||||||||||||

| Engum et al., 2007 34; Norway |

HUNT‐1 (1984–1986) and HUNT‐2 (1995–1997) N = 37 291 |

Age: 30–89 years Anxious/ depressed group Sex: 59.1% female Non‐anxious/ depressed group 51.0% female |

Self‐report (type of diabetes determined by using glutamic acid decarbox‐ylase, C‐peptide tests, and start of insulin treatment) |

Baseline: ADI Follow‐up HADS‐A: > 8 anxiety |

ADI: General self‐report anxiety symptoms HADS‐A: Past‐week self‐reported anxiety symptoms |

N = 2841 incident cases Follow‐up: 10 years |

Logistic regression | Age, gender, educational level, and marital status | ‐ | ‐ |

Type 1 diabetes

OR 0.47 (0.15–1.51) Type 2 diabetes OR 0.76 (0.42–1.37) |

Type 1 diabetes

OR 0.50 (0.16‐1.61) Type 1 diabetes OR 0.76 (0.42–1.37) |

| Marrie et al., 2016 29; Canada |

Administrative data from Alberta N = 50 818 (9624 persons with MS, and 41 194 matches) |

Age: mean ~ 42.8 years MS cases Sex: 68.9% female Controls Sex: 67.0% female |

ICD‐9 or 10 codes | ICD codes for anxiety disorders |

Anxiety disorders Length: not specified. |

No information incident anxiety Follow‐up: ~ 10 years |

Cox proportional hazards models | Age, sex, index year (for MS), SES | – | Hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, hyperlipidaemia, lung disease, fibromyalgia, epilepsy, inflammatory bowel disease (physical comorbidities time‐varying) | ‐ |

Combined populations

HR 1.11 (0.99–1.25) Matched controls HR 1.09 (0.95–1.24) MS population only HR 1.22 (0.94–1.58) |

ADI, Anxiety and Depression Inventory; HADS‐A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; MS, multiple sclerosis; OR, odds ratio; PCL‐C, PTSD checklist Civilian version; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD, post‐traumatic stress disorder; RR, risk ratio; VA: Veterans Affairs

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies

| Author, year | NOS score (maximum 9) | ROBINS‐I overall risk of bias | Most important study limitations and strengths (qualitative assessment) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al., 2015 22 | 9 | Low/moderate |

Limitations: Used self‐report trait anxiety scale split into data‐driven quartiles rather than validated cut‐offs being used. Strengths: Large, representative multi‐ethnic cohort. Comprehensive diabetes assessment (excluded people possible undiagnosed diabetes). Comprehensive set of confounders controlled for. |

| Atlantis et al., 2012 33 | 5 | Serious |

Limitations: Lack of confounder control. Short length of follow‐up and few people developed diabetes. Main analysis based on 10‐point increase in anxiety scores (not a validated cut‐off). Strengths: Large population specifically sampled for anxiety and depression. Event data for anxiety disorders based on diagnostic interviews available. |

| Boyko et al., 2010 23 | 5 | Moderate |

Limitations: Military population only so limited generalizability. Fully adjusted analysis was a backwards multiple regression so fully adjusted estimates of interest could not be included. Self‐report scales for anxiety (although applied diagnostic criteria) and self‐report diabetes. Strengths: Large sample size. |

| Chien and Lin, 2016 36 | 8 | Moderate |

Limitations: Administrative database (may underestimate anxiety and diabetes). No control cardiometabolic confounders. No crude estimate. Diagnostic codes included disorders no longer considered anxiety disorders (e.g. PTSD). Strengths: Large non‐Western population. |

| Demmer et al., 2015 24 | 8 | Moderate |

Limitations: Used self‐report anxiety scale. Lack of control for cardiometabolic abnormalities (other than BMI). Strengths: Large representative population with long follow‐up. Comprehensive assessment of incident diabetes. |

| Deschênes et al., 2016 25 | 6 | Moderate |

Limitations: Oversampled people with depression and metabolic abnormalities from pre‐existing dataset not representative population. Low diabetes incidence. Ethnically homogenous sample. Strengths: Large sample. Stratification by prediabetes status. Comprehensive set of confounders controlled for. |

| Engum et al., 2007 34 | 5 | / |

Limitations: Different assessment baseline and follow‐up anxiety. No control cardiometabolic confounders. Self‐report anxiety and diabetes. No description missing data. Ascertainment bias possibility (only one follow‐up in 10 years). Strengths: Large representative sample. |

| Edwards and Mezuk, 2012 26 | 6 | Moderate/serious |

Limitations: Lack of transparency in describing follow‐up data. Self‐report diabetes. No description time‐frame for anxiety. Relatively small number of participants with anxiety. Lack of control for cardiometabolic abnormalities (other than BMI). Strengths: Large representative sample, some ethnic diversity. Used diagnostic interviews for anxiety. |

| Farvid et al., 2014 27 | 8 | Moderate |

Limitations: Healthcare professional populations only so limited generalizability. Self‐report anxiety scale assessing personality phobic anxiety rather than phobic anxiety disorder. Ethnically homogenous sample. Strengths: Results from three studies provided. Large samples and long follow‐ups. Comprehensive assessment of diabetes. |

| Khambaty et al., 2017 28 | 8 | Moderate |

Limitations: Short anxiety screen rather than full anxiety scale or diagnostic interview. Non‐representative clinical population. Strengths: Large population. Comprehensive assessment of diabetes. Transparency in reporting. Ethnically diverse sample. |

| Marrie et al., 2016 29 | 7 | Moderate/serious |

Limitations: Not a representative study so limited generalizability (people with MS and matched controls). Administrative database (may underestimate anxiety and diabetes). No control cardiometabolic confounders. Strengths: Large sample size. |

| Miller‐Archie et al., 2014 30 | 8 | Moderate |

Limitations: Not a representative sample (only people exposed to 9/11 disaster). PTSD only assessed (no longer anxiety disorder in DSM‐V). PTSD and diabetes assessed with self‐report. Not all confounders measured at baseline. Strengths: Large sample. |

| Pérez‐Piñar et al., 2016 35 | 8 | Moderate/serious |

Limitations: Primary care database (may underestimate anxiety and diabetes). No description time‐frame for anxiety. Lack of control for cardiometabolic abnormalities. Unadjusted estimates not available. Strengths: Large ethnically diverse sample. |

| Scherrer et al., 2011 31 | 5 | Serious |

Limitations: Veteran population only so limited generalizability. Administrative database (may underestimate anxiety and diabetes). Limited adjustment for confounders. Strengths: Large sample size |

| Shirom et al., 2010 37 | 8 | Moderate |

Limitations: Self‐report anxiety symptoms. Women under‐represented in sample and people with high SES overrepresented (sample not generalizable). PTSD only assessed (no longer anxiety disorder in DSM‐V). Strengths: Good sized sample. Comprehensive set of confounders controlled for. |

| Vaccarino et al., 2014 32 | 7 | Low/moderate |

Limitations: Veteran population only so limited generalizability. Self‐report diabetes. Ethnically homogenous sample. Strengths: Large sample. Used diagnostic interviews for anxiety. Comprehensive set of confounders controlled for. |

NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. For this scale studies were ranked out of nine stars for selection bias, information bias, comparability and quality.

ROBINS‐I (Risk of Bias in Non‐randomised studies of Interventions). For this scale studies were ranked for bias across six domains (confounding, selection of participants, classification of intervention, missing data, measurement of outcomes, reporting of results).

Qualitative assessment: the two study reviewers independently assessed the main strengths and limitations of the included studies.

Because of the small number of studies examining diabetes to anxiety (n = 2) we put forward only those studies examining anxiety to diabetes for the quantitative synthesis (n = 14).

Study review

Anxiety to incident diabetes

In the 14 studies that examined the association between anxiety and incident diabetes, 115 418 people from a total of 1 760 800 (6.6%) developed incident diabetes (Table 1). Seven of the ten studies that provided an unadjusted or minimally adjusted estimate reported a significant association between baseline anxiety and incident diabetes 23, 24, 25, 27, 30, 31, 33. Of the 13 studies that examined the most adjusted association between baseline anxiety and incident diabetes, eight found a significant association 23, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 35, 36. Overall study quality was variable with 10 studies having low or moderate evidence of bias (see Table 2) and four having some serious bias issues 26, 33, 35, 37. In studies identified as having serious bias, bias was due to issues with adjustment for confounders, lack of transparency in reporting and participant sampling (Table 2).

Of the seven studies that found a significant least adjusted association between baseline anxiety and incident diabetes, two examined general anxiety symptoms 24, 33. Atlantis et al. 33 found that for every 10‐point increase in the Beck Anxiety Index score there was a 1.6‐fold increase in the odds of developing incident diabetes over 2 years. However, they did not provide an adjusted estimate. Demmer et al. 24 found that in women only, high anxiety symptoms as measured with the General Well‐Being Scale were associated with a 2.15 times increased likelihood of developing diabetes over 17 years. However, this association was attenuated after adjustment for sociodemographics, BMI and lifestyle characteristics, and no association between anxiety and diabetes was found in men 24. A further two studies found an association between generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or GAD symptomatology with incident diabetes 25, 31. Deschênes et al. 25 stratified their groups based on the presence of prediabetes and high anxiety symptoms measured with the GAD‐7 scale at baseline. They found that people with high anxiety and prediabetes had a 10.95 times increased odds of developing diabetes over 5 years compared with people with no prediabetes and no anxiety. This association remained significant after adjustment for a range of sociodemographic, cardiometabolic, lifestyle and medication confounders 25. However, this study also found that high anxiety symptoms in the absence of prediabetes were not associated with increased odds of developing diabetes (Table 1). Scherrer et al. 31, using data from a Veteran's database, found that doctor‐diagnosed GAD at baseline was associated with a 1.07 times increased hazard of developing incident diabetes over 6 years. This association remained significant after adjustment, however the authors only adjusted for BMI and age 31.

Of the four studies that examined the association between PTSD and incident anxiety 23, 30, 31, 32, three found a significant association. Scherrer et al. 31 found that veterans with doctor‐diagnosed PTSD at baseline had a 1.25 times increased hazard of developing incident diabetes, an association that remained significant after adjustment for BMI and age. Boyko et al. 23 examined PTSD in a military population using a validated scale and found those endorsing PTSD symptoms had a 2.56 times increased odds of developing incident diabetes over 3 years, an association that remained significant after adjustment for sociodemographics and BMI. They also found that panic and other anxiety also predicted incident diabetes. Miller‐Archie et al. 30 examined symptoms of PTSD in people exposed to a traumatic event and found that high baseline PTSD symptoms were associated with a 1.73 times increased odds of developing incident diabetes, an association that remained significant after controlling for sociodemographics and cardiometabolic abnormalities.

One article included data from three studies conducted in healthcare professionals and found that phobic anxiety symptoms at baseline were associated with an increased hazard of developing incident diabetes over 18–20 years in all three studies 27. However, the association in the study that only included men (Healthcare Professionals Study) was no longer significant after adjustment for confounders, whereas the two studies in women (Nurses Health Studies I and II) remained significant 27.

Of the four studies that did not provide unadjusted or minimally adjusted estimates, three found a significant association between baseline anxiety and incident diabetes28, 35, 36. Chien and Lin 36 used data from a Taiwanese insurance database to determine that diagnosed anxiety disorders were associated with a 1.34 times increased risk of developing incident diabetes over 5 years after adjusting for sociodemographics. Khambaty et al. 28 measured anxiety with a short screening scale in older adults and found that after adjusting for sociodemographics, cardiometabolic characteristics and smoking, those with anxiety had a 1.36 times increased hazard of incident diabetes over 10 years. Pérez‐Piñar et al. 35 used read codes in a primary care database to determine that diagnosed anxiety disorders were associated with a 1.14 times increased hazard of developing diabetes over 10 years after adjusting for sociodemographics and medication.

In total, three studies indicated there was no unadjusted or minimally adjusted association between either trait anxiety with incident diabetes 22, anxiety disorders with incident diabetes 26 or PTSD symptoms with incident diabetes 32.

There was study heterogeneity in terms of follow‐up, measurement, population and analysis (Table 1). Study follow‐up ranged between 2 years 33 and 20 years 27, 37. Studies with a shorter range of follow‐up (2–5 years) reported overall diabetes incidence rates of 0.01% to 3.5% 23, 25, 33 compared with overall diabetes incidence rates of 4.4% to 25.9% in studies with a follow‐up of 10 years or more 22, 24, 26, 28, 32, 35, 37. Types of anxiety measurements included the assessment of non‐specific anxiety symptoms, a composite of different anxiety disorders, PTSD, phobic anxiety symptoms, panic, GAD and/or other anxiety (Table 1). Anxiety was determined using a variety of validated symptom scales 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 33, 37, diagnostic interviews 26, 32, 33 and examination of medical records 31, 35, 36. Most studies examined general anxiety or defined anxiety or anxiety disorders using DSM‐V criteria 22, 24, 28, 33, 35, 37. However, three studies included anxiety disorders as defined by DSM‐IV 23, 31, 36 and two studies only provided estimates for PTSD 30, 32.

All studies excluded people with diagnosed diabetes at baseline. Four studies also excluded people with high levels of blood glucose t baseline and assessed incident diabetes using blood glucose levels 22, 28, 33, 37. One study also explicitly accounted for prediabetes in their analysis 25. The remaining nine studies relied on self‐report or medical records, and therefore undiagnosed diabetes could be an issue with these studies (Table 1). Notably, most incident cases included in this direction of causality would have assessed incident Type 2 diabetes as studies were conducted in adult populations (Table 1).

There were also differences in the populations studied (Table 1). Three studies were conducted in veteran or military populations 23, 31, 32, one study examined healthcare professionals 27, one study was conducted in people exposed to the 9/11 attacks in New York 30, two studies sampled people from a health insurance database 36, 37, two studies sampled people from primary care 28, 35, one study sampled a mixture of clinical and community populations 33 and the remaining four studies were sampled from the community 22, 24, 25, 26. Furthermore, two studies oversampled people on the basis of anxiety and/or depression at baseline 25, 33.

Finally, there were differences in the analyses employed by researchers, with six studies calculating ORs, two studies calculating risk ratios (RRs) and six studies calculating hazards ratios (HRs) (Table 1). Furthermore, one study did not control for any confounders 33, one study only controlled for age and BMI 31 and one study only controlled for sociodemographic confounders 36, whereas most studies controlled for a range of sociodemographic, cardiometabolic and other confounders [22, 24, 28, 30, 32, 37].

Diabetes to incident anxiety

Only two studies examined the association between diabetes and incident anxiety (Table 1). Both studies had moderate to serious quality issues (Table 2). The first study by Engum et al. 34 found no association between either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes and incident anxiety symptoms over 10 years in a Norwegian population sample. Although the study included a large and representative sample, they used a different measure for anxiety at baseline and follow‐up, thereby limiting inferences about incidence (Table 1). The second study by Marrie et al. 29 provided only fully adjusted estimates and found no association between diabetes and incident anxiety in an administrative database over 10 years of follow‐up. However, generalizability was limited by the fact that participants were sampled based on a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis or being a matched‐control for multiple sclerosis participants. Both studies found no association from diabetes to incident anxiety, however due to study quality and generalizability, inferences are limited.

Implications of study review for meta‐analysis

Because of the small number of studies for the direction of association from diabetes to incident anxiety, we could not move forward with a meta‐analysis for this direction. However, we had sufficient data to examine the direction of association from anxiety to incident diabetes. Owing to differences in analysis (Table 1) we opted to combine all studies for a least adjusted estimate using ORs or raw event data (either calculated from data provided in the paper or by contacting study authors) that were then converted to ORs (Table S3). Furthermore, as one paper had analysed results from three studies separately 27, we opted to enter each study independently into the meta‐analysis. Owing to study heterogeneity, we then ran a series of sensitivity analyses on our results to determine whether those sources of heterogeneity we identified in our review would have any impact on the combined estimate. We opted to run a series of analyses stratified by definition of anxiety given that the current definition of anxiety disorders no longer includes disorders such as PTSD and OCD (DSM‐V), which were previously classified as anxiety disorders (DSM‐IV). We also examined most‐adjusted data, but these analyses were stratified by the estimate provided by the authors (i.e. OR or HR).

Meta‐analysis

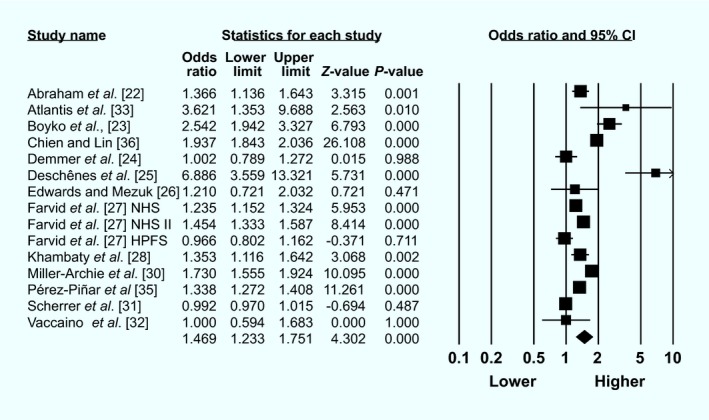

Results from 15 studies across 13 publications were entered into a random‐effects meta‐analysis (Fig. 2). Unadjusted or age‐adjusted ORs and raw event data were combined (Table S3). We were unable to access raw data for one study 37, however all other studies were included.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of least‐adjusted association between baseline anxiety and incident diabetes

The pooled OR from the 15 studies was 1.47 (1.23–1.75). However, study heterogeneity was high (I 2 = 98.13) and the funnel plot (Fig. S1) and Egger's test (P = 0.05) indicated the presence of publication bias. In analyses stratified by anxiety assessment type, diabetes assessment type, and most other general sensitivity analyses, the estimate mostly remained stable (Table 3). However, there was no significant association between anxiety and incident diabetes in sensitivity analyses that combined only studies that assessed baseline diagnosed anxiety disorders (as defined by DSM‐V criteria), studies that had some serious risk of bias, and studies that provided stratified estimates for men.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis and funnel plot for least‐adjusted analysis

| Odds ratio | I 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| All studies | 1.47 (1.23–1.74) | 98.13 |

| Minus largest study (Pérez‐Piñar et al. 35) | 1.49 (1.22–1.82) | 98.20 |

| Minus most significant study (Deschênes et al. 25) | 1.38 (1.61–1.65) | 98.1 |

| Low‐moderate risk of bias studies | 1.58 (1.53–1.64) | 94.8 |

| Some serious risk of bias studies | 1.25 (0.93–1.68) | 86.7 |

| Follow‐up 5 years or less | 1.96 (1.87–2.06) | 82.5 |

| Follow‐up 10 years or more | 1.28 (1.24–1.33) | 78.7 |

| Only including anxiety/anxiety disorder as defined in DSM‐V | 1.36 (1.17–1.60) | 94.7 |

| Anxiety disorders (DSM‐V) | 1.24 (0.88–1.74) | 97.6 |

| Anxiety symptoms (DSM‐V) | 1.43 (1.22–1.67) | 86.7 |

| PTSD only | 1.51 (1.07–2.13) | 95.9 |

| Anxiety symptoms (with PTSD) | 1.46 (1.28–1.71) | 89.5 |

| Studies where people with possible undiagnosed diabetes at baseline excluded. | 1.42 (1.15–1.76) | 46.5 |

| Community population | 1.86 (1.14–3.04) | 88.0 |

| Men | 0.93 (0.79–1.09) | 0 |

| Women | 1.35 (1.17–1.55) | 76.1 |

DSM‐V anxiety disorders include: generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic, phobia. However, they no longer include post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) which were classified as anxiety disorders until 2013. For those studies only including DSM‐V anxiety disorders or anxiety we excluded PTSD from the combined estimate for Boyko et al. 23 and excluded PTSD from the combined estimate for Scherrer et al. 31. Anxiety disorders (DSM‐V) comprises only those studies where a diagnosis of anxiety disorders as defined by DSM‐V was included (thus Chien and Lin 36 were excluded as they combined PTSD and OCD in their anxiety disorder estimate).

When we examined the most adjusted associations stratified by type of analysis, all estimates indicated a significant association between baseline anxiety with incident diabetes (Table 4). The eight studies that calculated an adjusted HR estimate had a combined estimate of HR 1.14 (1.08–1.21) (for forest plot see Fig. S2). Study heterogeneity was high for these studies (I 2 = 71.94), however there was little evidence of publication bias (Egger's test, P = 0.38; see Fig. S1 for funnel plot). The five studies that calculated an adjusted OR had a combined estimate of OR 1.64 (1.13–2.39) (for forest plot see Fig. S2). Study heterogeneity was high (I 2 = 84.13), however Egger's test was non‐significant (P = 0.20; see Fig. S1 for funnel plot). Finally, the two studies that calculated an adjusted RR had a combined estimate of RR 1.34 (1.27 1.41) (for forest plot see Fig. S2). Study heterogeneity was low for these studies (I 2 = 0).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses and funnel plots for most‐adjusted meta‐analysis anxiety to diabetes stratified by analysis type

| Hazard ratio | Odds ratio | Risk ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) | 1.64 (1.13–2.39) | 1.34 (1.27–1.41) |

| Minus largest study | 1.12 (1.03–1.23) | 1.48 (0.99–2.20) | – |

| Minus most significant study | 1.13 (1.06–1.20) | 1.42 (1.03–1.95) | – |

| Low–moderate risk of bias studies | 1.13 (0.99–1.28) | 1.81 (1.19–2.75) | – |

| Some serious risk of bias studies | 1.15 (1.13–1.18) | Insufficient data (only Edwards and Mezuk 26) | – |

| Follow up 5 years or less | No studies | 3.09 (1.41–6.76) | – |

| Follow up 10 years or more | 1.14 (1.04–1.24) | 1.15 (0.85–1.56) | – |

| Only including anxiety/anxiety disorder as in DSM‐V | 1.14 (1.09–1.20) | 2.06 (1.46–2.91) | – |

| Anxiety disorder (DSM‐V) | 1.15 (1.13–1.18) | Insufficient data (only Edwards and Mezuk 26) | – |

| PTSD only | Insufficient data (only Scherrer et al. 31) | 1.47 (1.06–2.03) | – |

| Anxiety disorder (DSM‐IV) | 1.15 (1.13–1.18) | Insufficient data (only Edwards and Mezuk 26) | – |

| Anxiety symptoms | 1.16 (1.13–1.18) | 1.81 (1.19–2.75) | – |

| Studies where people with possible undiagnosed diabetes at baseline excluded | 1.16 (1.13–1.18) | No studies | – |

| Studies where people with possible undiagnosed diabetes at baseline not excluded | 1.13 (1.07–1.21) | All studies | – |

| Outcome self‐report diabetes or doctor diagnosis | 1.13 (1.07–1.21) | All studies | – |

| Outcome diabetes validated with blood glucose levels | 1.16 (1.13–1.18) | No studies | – |

| Community population | Insufficient data (only Abraham et al. 22) | 1.89 (1.15–3.11) | – |

| Controlled for sociodemographic and cardiometabolic/adiposity | 1.16 (1.11–1.21) | 1.83 (1.12–2.98) | – |

| Controlled for sociodemographic, cardiometabolic/adiposity and lifestyle | 1.15 (1.06–1.25) | 2.21 (0.45–10.86) | – |

The following studies calculated hazards ratios: Abraham et al. 22, Farvid et al. 27, Khambaty et al. 28, Pérez‐Piñar et al. 35, Scherrer et al. 31 and Shirom et al. 37.

The following studies calculated odds ratios: Boyko et al. 23, Deschênes et al. 25, Edwards and Mezuk 26, Miller‐Archie et al. 30 and Vaccarino et al. 32.

DSM‐V anxiety disorders include: Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic, phobia. However, they no longer include PTSD and OCD which were classified as anxiety disorders until 2013. DSM‐IV anxiety disorders include: GAD, panic, phobia, PTSD, OCD.

We ran a series of sensitivity analyses for the HR and OR estimates (Table 4). The HR estimate remained significant except when we only examined studies that had a low–moderate risk of bias. The OR estimate was reduced to non‐significance when we removed the largest study 23, only assessed low–moderate quality studies, and only included studies that had controlled for a variety of sociodemographic, cardiometabolic/adiposity and lifestyle factors 25, 26. We could not run sensitivity analyses for the risk ratio estimate as only two studies were included.

Discussion

The results from this systematic review and meta‐analysis indicate that anxiety symptoms and disorders (as defined by both DSM‐IV and DSM‐V criteria) are associated with an increased risk of developing incident diabetes. Furthermore, our results indicate that the association between anxiety and incident diabetes persists even after adjusting for a range of sociodemographic, cardiometabolic and adiposity‐related confounders. However, the two studies that examined the direction of association from diabetes to incident anxiety found no evidence of an association, although inferences are limited by the small number of studies and quality issues.

Anxiety to diabetes

Previous work has hypothesized that anxiety could lead to an increased risk of diabetes 19, however, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first synthesis that confirms anxiety as a risk factor for incident diabetes.

The association between anxiety and an increased risk of incident diabetes is likely due to a nuanced and complex relationship between anxiety and other risk factors for diabetes. For example, anxiety is often comorbid with other psychiatric disorders shown to be associated with diabetes risk such as depression 26, 38. Thus, it is possible that the association between anxiety and diabetes could be driven, in part, by the comorbidity of anxiety with other psychological disorders such as depression 39. However, where studies adjusted for depression 22, 26, 32, the inclusion of depression into the statistical model did not substantially affect estimates. Furthermore, anxiety is associated with some behavioural risk factors that are linked with diabetes risk factors such as unhealthy lifestyle 12, sleep disturbance 13 and obesity 10. Anxiety is also linked with various biological changes that have been shown to increase the risk of diabetes such as inflammation 40 and cardiometabolic abnormalities 11.

Although results from this analysis do not provide us with information on how anxiety is linked with an increased risk of incident diabetes, they do indicate that anxiety is an independent risk factor for diabetes even when taking confounders into account. However, more work is needed on understanding pathways of how anxiety might lead to diabetes.

Diabetes to anxiety

Results from this review indicate that more research is needed on the direction of association from diabetes to anxiety because only two studies were eligible for inclusion in this review. Neither study that examined diabetes as a risk factor for incident anxiety identified a significant association. Despite this, other work we identified that was not eligible for inclusion in this review did indicate a possible association. Cooper et al. 41 found that young people with Type 1 diabetes (average age of 9 years at baseline) had a 2.5 times increased hazard of developing incident anxiety over 26 years. Furthermore, Huang et al. 38 found a higher annual incidence of people with diabetes being diagnosed with an anxiety disorder over 5 years using data for nearly 1 million people from a Taiwanese insurance base. However, this study was not included because the lowest baseline age was 15 years. In addition, Hasan et al. 42 found that diabetes was associated with a 2.6 times increased likelihood of having a current anxiety disorder after 6 years in Australian women (although they did not explicitly remove anxiety at baseline). This work indicates that there is a possibility that diabetes could lead to incident anxiety, although exclusion criteria for our study precluded the inclusion of many of these studies. Our work also indicates a need for more research to explicitly examine whether diabetes could lead to incident anxiety. Future work examining this direction of causation needs to be mindful of possible generalizability and bias issues. For example, ascertainment bias is more likely to be an issue with studies examining incident anxiety than incident diabetes as anxiety is more likely to have a diverse life course 43, which could limit the likelihood of capturing an event. Furthermore, as anxiety disorder tends to occur in adolescence or early adulthood 44 the approach taken by Cooper et al. 41 following people up from a younger age may better allow us to make inferences on diabetes as a cause of incident anxiety.

Clinical implications

This work adds to the body of evidence suggesting that poor mental health is an important diabetes risk factor. Previous work has found evidence that depression 45, PTSD 46 and stress 19 can increase a person's risk of developing diabetes. This is likely a complex association via various and likely interacting pathways. However, screening for and integrating treatment for mental illness into diabetes prevention programs could be important for helping to reduce the increasing prevalence of diabetes.

Despite work from this review indicating that diabetes may not be associated with an increased risk of incident anxiety, there is still evidence that anxiety is an important comorbidity to consider in people with diabetes. Anxiety is associated with poorer outcomes in people with diabetes such as poorer glycaemic control 47, worsened functioning 48 and increased diabetes complications 49. As such, it is important for care providers to integrate the screening and treatment of mental health conditions such as anxiety into diabetes care 50.

Strengths and limitations

There are limitations that must be acknowledged within this review. First, there were indications that publication bias may be an issue with this review and there was also notable theoretical and statistical heterogeneity evident. Therefore, results should be interpreted with caution. There were differences in anxiety assessment, diabetes assessment, populations studied and analyses conducted. However, we were mindful of this limitation in our presentation and analysis. We also only screened studies in French and English meaning there could also be language bias present. Furthermore, setting our inclusion age to 16 years meant that we had to exclude some studies that provided compelling evidence on the longitudinal relationship between anxiety and diabetes (e.g. Cooper et al. 41). In addition, there are also possibly issues with only examining anxiety ‘cases’. There is a possibility that below‐threshold anxiety symptoms could also lead to an increased risk of incident diabetes, however, we were unable to determine this using data from the included studies. Therefore, future work could examine how below‐threshold anxiety symptoms are associated longitudinally with diabetes.

There are also limitations with examining both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes when determining longitudinal associations between anxiety and diabetes. Those studies that examined anxiety as a cause of incident diabetes are more likely to capture people with Type 2 diabetes due to the earlier onset of Type 1 diabetes. However, those studies that examined diabetes as a cause of incident anxiety are arguably better conducted in people with Type 1 diabetes as they could be followed up from a younger age allowing us to better capture first cases of anxiety. It is feasible that the best way to determine causality between diabetes and anxiety would be to take a life course approach to determine the incidence of anxiety and/or diabetes while taking the date of diabetes diagnosis into account. Future work could also stratify analyses by diabetes type.

However, despite these limitations there are several strengths to the present review. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first synthesis to systematically investigate the longitudinal association between anxiety and diabetes in a large number of databases. Furthermore, we undertook a comprehensive quality assessment and heterogeneity assessments to determine the stability of estimates and potential sources of differences in results.

Conclusions

Work from this analysis indicates that anxiety may be a risk factor for incident diabetes. However, heterogeneity between studies and evidence of publication bias suggest that results should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, there was limited evidence that investigated the direction of association from diabetes to incident anxiety indicating the need for future work to investigate this direction of causality.

Funding sources

None.

Competing interests

None declared.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Funnel plots.

Figure S2. Forest plots for more adjusted analyses.

Table S1. Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale Quality Assessment.

Table S2. ROBINS‐I quality assessment.

Table S3. Raw event data extracted from paper or requested from author.

Document S1. Search strategy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Bonnie Au for her help with conducting a scoping review for this work and Chantelle Mangejawa for her help with searching grey area literature.

Diabet. Med. 35, 677–693 (2018)

References

- 1. International Diabetes Federation (IDF) . International Diabetes Federation Atlas, 7th Edition Brussels: IDF, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balhara YPS. Diabetes and psychiatric disorders. Indian J Endocrin Metab 2011; 15: 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. JAMA 2014; 312: 691–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015; 17: 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martin P. The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: a review. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2003; 5: 281–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baxter A, Vos T, Scott K, Ferrari A, Whiteford H. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol Med 2014; 44: 2363–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Tolin DF. Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: a meta‐analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2007; 27: 572–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roest AM, Martens EJ, de Jonge P, Denollet J. Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart disease: a meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gariepy G, Nitka D, Schmitz N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Obes 2010; 34: 407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sardinha A, Nardi AE. The role of anxiety in metabolic syndrome. Expert Rev Endocrin Metab 2012; 7: 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bonnet F, Irving K, Terra J‐L, Nony P, Berthezène F, Moulin P. Anxiety and depression are associated with unhealthy lifestyle in patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2005; 178: 339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jansson‐Fröjmark M, Lindblom K. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. J Psychosom Res 2008; 64: 443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nouwen A, Winkley K, Twisk J, Lloyd C, Peyrot M, Ismail K et al Type 2 diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for the onset of depression: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Diabetologia 2010; 53: 2480–2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katon WJ. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011; 13: 7–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Turner J, Kelly B. Emotional dimensions of chronic disease. Western J Med 2000; 172: 124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grigsby AB, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53: 1053–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith KJ, Béland M, Clyde M, Gariépy G, Pagé V, Badawi G et al Association of diabetes with anxiety: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Psychosom Res 2013; 74: 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pouwer F, Kupper N, Adriaanse MC. Does emotional stress cause type 2 diabetes mellitus? A review from the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) Research Consortium. Discov Med 2010; 9: 112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M et al The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta‐analyses. 2009. Available at http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm Last accessed 1 May 2017.

- 21. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M et al ROBINS‐I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non‐randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016; 355: i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abraham S, Shah NG, Roux AD, Hill‐Briggs F, Seeman T, Szklo M et al Trait anger but not anxiety predicts incident type 2 diabetes: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015; 60: 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boyko EJMD, Jacobson IGMPH, Smith BPHD, Ryan MAKMD, Hooper TIMD, Amoroso PJMD et al Risk of diabetes in U.S. military service members in relation to combat deployment and mental health. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 1771–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Demmer RT, Gelb S, Suglia SF, Keyes KM, Aiello AE, Colombo PC et al Sex differences in the association between depression, anxiety, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Psychosom Med 2015; 77: 467–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deschênes SS, Burns RJ, Graham E, Schmitz N. Prediabetes, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and risk of type 2 diabetes: a community‐based cohort study. J Psychosom Res 2016; 89: 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edwards LE, Mezuk B. Anxiety and risk of type 2 diabetes: evidence from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. J Psychosom Res 2012; 73: 418–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farvid MS, Qi L, Hu FB, Kawachi I, Okereke OI, Kubzansky LD et al Phobic anxiety symptom scores and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. Brain Behav Immun 2014; 36: 176–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khambaty T, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Stewart JC. Depression and anxiety screens as simultaneous predictors of 10‐year incidence of diabetes mellitus in older adults in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65: 294–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marrie RA, Patten SB, Greenfield J, Svenson LW, Jette N, Tremlett H et al Physical comorbidities increase the risk of psychiatric comorbidity in multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav 2016; 6: e00493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller‐Archie SA, Jordan HT, Ruff RR, Chamany S, Cone JE, Brackbill RM et al Posttraumatic stress disorder and new‐onset diabetes among adult survivors of the World Trade Center disaster. Prevent Med 2014; 66: 34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scherrer JF, Lustman PJ, Chrusciel T, Garfield LD, Freedland KE, Carney RM et al Posttraumatic stress disorder is a risk factor for incident diabetes. Psychosom Med 2011; 73: A58. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vaccarino V, Goldberg J, Magruder KM, Forsberg CW, Friedman MJ, Litz BT et al Posttraumatic stress disorder and incidence of type‐2 diabetes: a prospective twin study. J Psychiatr Res 2014; 56: 158–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Atlantis E, Vogelzangs N, Cashman K, Penninx BJWH. Common mental disorders associated with 2‐year diabetes incidence: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Affect Disord 2012; 142(Suppl): S30–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Engum A. The role of depression and anxiety in onset of diabetes in a large population‐based study. J Psychosom Res 2007; 62: 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pérez‐Piñar M, Mathur R, Foguet Q, Ayis S, Robson J, Ayerbe L. Cardiovascular risk factors among patients with schizophrenia, bipolar, depressive, anxiety, and personality disorders. Eur Psychiat 2016; 35: 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chien IC, Lin CH. Increased risk of diabetes in patients with anxiety disorders: A population‐based study. J Psychosom Res 2016; 86: 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shirom A, Toker S, Jacobson O, Balicer RD. Feeling vigorous and the risks of all‐cause mortality, ischemic heart disease, and diabetes: a 20‐year follow‐up of healthy employees. Psychosom Med 2010; 72: 727–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang CJ, Wang SY, Lee MH, Chiu HC. Prevalence and incidence of mental illness in diabetes: a national population‐based cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011; 93: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stavrakaki C, Vargo B. The relationship of anxiety and depression: a review of the literature. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 149: 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Culpepper L. Generalized anxiety disorder and medical illness. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70(Suppl 2): 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cooper M, Lin A, Alvares G, de Klerk N, Jones T, Davis E. Psychiatric disorders during early adulthood in those with childhood onset type 1 diabetes: rates and clinical risk factors from population‐based follow‐up. Pediatr Diabetes 2017; 18: 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hasan SS, Clavarino AM, Dingle K, Mamun AA, Kairuz T. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of depressive and anxiety disorders in Australian women: a longitudinal study. J Women's Health (Larchmt) 2015; 24: 889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nandi A, Beard JR, Galea S. Epidemiologic heterogeneity of common mood and anxiety disorders over the lifecourse in the general population: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2009; 9: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age‐of‐onset distributions of DSM‐IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiat 2005; 62: 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rotella F, Mannucci E. Depression as a risk factor for diabetes: a meta‐analysis of longitudinal studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Steel Z, Lederman O, Lamwaka AV et al Type 2 diabetes among people with posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychosom Med 2016; 78: 465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, De Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta‐analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 934–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Deschênes SS, Burns RJ, Schmitz N. Anxiety symptoms and functioning in a community sample of individuals with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. J Diabetes 2016; 8: 854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Collins M, Corcoran P, Perry I. Anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with diabetes. Diabet Med 2009; 26: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Young‐Hyman D, De Groot M, Hill‐Briggs F, Gonzalez JS, Hood K, Peyrot M. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 2126–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Funnel plots.

Figure S2. Forest plots for more adjusted analyses.

Table S1. Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale Quality Assessment.

Table S2. ROBINS‐I quality assessment.

Table S3. Raw event data extracted from paper or requested from author.

Document S1. Search strategy.