Abstract

Background and objectives

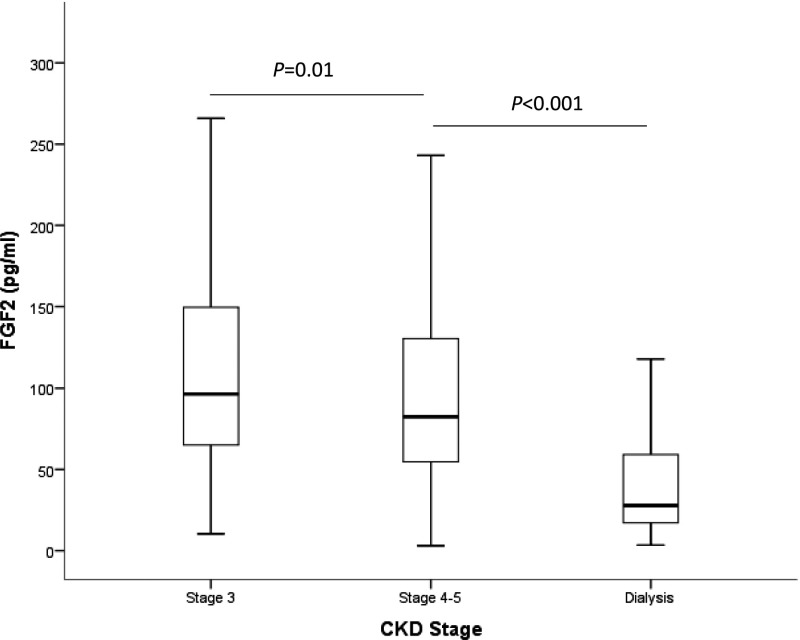

Atherosclerosis is highly prevalent in CKD. The rate of progression of atherosclerosis is associated with cardiovascular events. Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) is a member of the FGF family with potentially both protective and deleterious effects in the development of atherosclerosis. The role of circulating FGF-2 levels in the progression of atherosclerosis in CKD is unknown.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We used a multicenter, prospective, observational cohorts study of 481 patients with CKD. We determined the presence of atheroma plaque in ten arterial territories by carotid and femoral ultrasounds. Progression of atheromatosis was defined as an increase in the number of territories with plaque after 24 months. Plasma levels of FGF-2 were measured by multiplex analysis. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to determine whether plasma FGF-2 levels were associated with atheromatosis progression.

Results

Average age of the population was 61 years. The percentage of patients in each CKD stage was 51% in stage 3, 41% in stages 4–5, and 8% in dialysis. A total of 335 patients (70%) showed plaque at baseline. Atheromatosis progressed in 289 patients (67%). FGF-2 levels were similar between patients with or without plaque at baseline (79 versus 88 pg/ml), but lower in patients with atheromatosis progression after 2 years (78 versus 98 pg/ml; P<0.01). In adjusted analyses, higher plasma FGF-2 was associated with lower risk of atheromatosis progression (odds ratio [OR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.76 to 0.96; per 50 pg/ml increment). Analysis of FGF-2 in tertiles showed that atheroma progression was observed for 102 participants in the lowest tertile of FGF-2 (reference group), 86 participants in the middle tertile of FGF-2 (adjusted OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.40 to 1.20), and 74 participants in the lowest tertile of FGF-2 (adjusted OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.82).

Conclusions

Low FGF-2 levels are independently associated with atheromatosis progression in CKD.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis; cardiovascular disease; Humans; Plaque, Atherosclerotic; Fibroblast Growth Factor 2; Prospective Studies; Logistic Models; Atherosclerosis; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Disease Progression; arteries; renal dialysis

Introduction

CKD is a growing public health problem worldwide and, over the past decade, it has developed into an area of intensive clinical and epidemiologic research. Patients with CKD, even at early stages, demonstrate higher risk for the development of cardiovascular disease (1,2), enhancing morbidity and mortality in this population (3). A variety of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia (2), and nontraditional variables such as endothelial cell dysfunction (4), inflammation (2), low vitamin D levels (5,6), or hyperphosphatemia (7–9) begin to act very early in the course of CKD, accelerating the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Taking into account that traditional and CKD-specific risk prediction equations explain only a portion of the cardiovascular disease associated with CKD, the search for new risk factors for cardiovascular disease in patients with CKD continues.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is highly prevalent in patients with CKD (7) and its progression is closely associated with the progression of CKD (10). The role of atherosclerosis in the increased cardiovascular mortality in patients with CKD seems clear, although its contribution in late stages is controversial. Indeed, there are differences in the type of cardiovascular events and the associated factors along the progression of CKD. Thus, in early stages, there is a high mortality rate due to ischemic events, related to atherosclerosis (11). However, in patients on dialysis, most of the deaths seem to be caused by heart failure and sudden cardiac death, although subclinical atherosclerosis appears to be influencing the higher susceptibility of the myocardium of those patients to electrolyte imbalances (12). Indeed, atheroma burden also independently predicts cardiovascular events in dialysis, and the rate of atherosclerotic plaque formation predicts cardiovascular events in those patients (13). Therefore, the determination of factors that affect atherosclerosis progression in CKD could lead to therapeutic targets specific for patients with CKD.

Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2 or bFGF) is a member of a large family of heparin-binding proteins (14), and plays an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, but it also has cardioprotective actions. FGF-2 affects essential biologic activities of vascular cells such as differentiation, proliferation, and migration, showing a dual role in the cardiovascular system. The expression of FGF-2 and its receptors in a normal vessel wall is highly beneficial for the maintenance of the vascular homeostasis and protection of endothelial cells (15). However, FGF-2 and its receptors play a role in the inflammatory process, intimal thickening, and intraplaque angiogenesis (16), stimulating proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) (14,17) and development of vasa vasorum in atherosclerotic lesions (18), therefore accelerating atherosclerotic plaque growth.

There are scarce clinical data investigating the role of circulating levels of FGF-2 in atherosclerosis. Only a few studies have demonstrated that levels of FGF-2 did not correlate with carotid obstruction grade (19) or coronary artery calcification in the general population (4). However, to date, no investigation has been conducted analyzing the role of circulating FGF-2 levels in atheromatosis progression. In this work, we analyzed the association between FGF-2 and progression of atheromatosis burden in a subpopulation of the National Observatory of Atherosclerosis in Nephrology (NEFRONA) study.

Materials and Methods

Design and Study Population

The protocol of the study was approved by the ethics committee of each hospital and all patients were included after signing informed consent. This research followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The design and objectives of the NEFRONA study have been already published in detail (20,21). Briefly, 2445 patients with CKD (937 in CKD stage 3, 820 in stages 4–5, and 688 in dialysis) without a history of previous cardiovascular disease who were 18–75 years of age were enrolled from 81 Spanish hospitals between October of 2009 and June of 2011, with a scheduled follow-up visit after 24 months. Patients from the NEFRONA study who had hemodynamically significant stenotic carotid plaque, ankle-brachial index (ABI) <0.7 at baseline, a cardiovascular event or received a renal allograft along the 2 year follow-up, or died after the first ultrasound exploration were excluded from the follow-up. Thus, 1555 were followed for 24 months. Out of those, 481 had available plasma samples to measure FGF-2 levels. Samples from the other patients had already been spent to measure other biomarkers in sub-studies within the NEFRONA study (22,23). In any case, both populations did not differ in most of the parameters of the study, although there was a lower proportion of patients in dialysis than in the total sample. Consequently, high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were lower and 25-hydroxyvitamin D, total, and LDL cholesterol levels were higher in the analyzed sample (Supplemental Table 1).

Determination of FGF-2 in Plasma Samples

FGF-2 levels were measured in duplicate in frozen plasma samples after the end of the recruitment period. The detection was performed with multiplex kits (Milliplex MAP; Merck Millipore), an assay specially designed to identify ten different biomarkers in a small sample by an ELISA-like method. The assay uses internally color-coded microspheres coated with specific primary antibodies. After a molecule from a test sample is captured by the bead, an additional biotinylated antibody, built to identify another epitope of the molecule, is introduced. Thus, the emission of the bead identifies the compound and the intensity if the second antibody quantifies the amount of the compound. The multiplex panel included FGF-2, Eotaxin, GM-CSF, Fractalkine, IFN-γ, MDC, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1β, and VEGF. The purpose of the study was to identify whether those analytes, which have been previously associated with cardiovascular disease, were associated with atherosclerosis progression in CKD. Out of those, only FGF-2 showed an association with the outcome, after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

In order to determine whether the method of recollection of the samples was interfering with the results, we used the multiplex kit to measure 40 samples from in-house patients, frozen immediately after extraction, and compared the results against the same samples stored at 4°C for 24 hours (in order to mimic the conditions of the samples during the shipment from the extraction place to the biobank in which they were stored). The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.99 (P<0.001), showing that the handling of the samples before storage did not affect the levels of FGF-2. The interassay coefficient of variability of this analyte is 4.8%.

Clinical Data and Laboratory Examinations

Current health status, medical history, baseline cardiovascular risk factors, and drug use information was obtained at baseline. A physical examination was performed, consisting of anthropometric measures, standard vital tests, and ABI measurements as previously described (24). A pathologic ABI was described as ≤0.9 or ≥1.4. Biochemical data were obtained from a routine fasting blood test within 3 months from the vascular study. Previous and current smokers were classified as ever smokers. Diagnosis of dyslipidemia was obtained from the clinical history. GFR was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study formula (MDRD-4).

Ultrasound Imaging

B-mode ultrasound of the carotid and femoral arteries was performed using the Vivid apparatus (General Electric) equipped with a 6–13 MHz broadband linear array probe, as previously described (25). Briefly, ultrasound imaging was performed with the participant in a supine position and the head turned 45° contralateral to the side of the probe to evaluate carotid plaques. The presence of atheromatous plaques was defined as an intima-media thickness (IMT)>1.5 mm protruding into the lumen, according to the American Society of Echocardiography Consensus Statement (26) and the Mannheim IMT Consensus (27).

The presence of atheromatous plaques was explored in ten territories (both internal, bulb, and common carotids, and both common and superficial femoral arteries) by a single reader in blinded mode, using semiautomatic software (EchoPAC Dimension; General Electric Healthcare). Therefore, a score from 0 to 10 was assigned to every patient both at basal and at the follow-up exploration 2 years later; 0 meaning no plaques in any territory and 10 meaning the presence of atheroma plaque in all ten territories explored. To assess intraobserver reliability, a sample of 20 individuals was measured between three and five times on different days by a reader unaware of patients’ clinical history. An intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.8 was obtained for plaque assessment, indicating very good intraobserver reliability. IMT was only measured in arterial regions without plaque and calculated as the average between left and right sides. When a territory presented with plaque, the IMT value was censored to be 1.5 mm in that territory. The average of the IMT value of the ten territories was calculated and presented as the patient’s IMT value.

Evaluation of Progression

Atheromatosis progression was defined as an increase in the number of territories showing plaque with respect to the baseline visit, as previously used in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis study (28). The analysis was performed in ten arterial territories, yielding a score of 1–10 both at the baseline (SB) and at the follow-up (SFU) visit. The outcome variable (atheromatosis progression) was defined as an increase in the number of territories with plaque with respect to the basal visit. Thus, if SFU−SB>0, the patient was assigned to the group of progressors. If SFU−SB=0, the patient was assigned to the group of nonprogressors. We did not observe a negative value (SFU−SB) in any patient.

Statistical Analyses

Univariable relationship between the levels of the ten compounds measured in the multiplex analysis with plaque presence and progression at 24 months was analyzed by t test for normally distributed variables, and Mann–Whitney U test in nonparametric analysis. In order to account for the multiple testing problem, Bonferroni correction was applied. Thus, only P values ≤0.01 were considered statistically significant in the univariate analysis. Significant variables in univariable analyses and potential confounders were used to develop appropriate multivariable logistic regression models. A forward step procedure was used to build the multivariable model, including the variable showing maximum contribution identifying those patients with 24-month atheromatosis progression, according to the likelihood ratio test. Those variables without a statistically significant contribution, but modifying in >10% the value of the coefficients of any of the significant variables when removed from the model, were considered confounders and included in the final model. Possible first-degree interactions between FGF-2 and different parameters were tested. A statistical significance level of 0.05 was used. A sensitivity analysis using FGF-2 as a categorical variable was also built. All analyses were made using a standard statistical package (SPSS 24.0).

Results

The characteristics of the population, grouped by tertiles of FGF-2, are shown in Table 1. The median age was 61 years, and the median (25th to 75th percentiles) plasma FGF-2 levels were 85 (55–138) pg/ml. Table 2 shows the univariable analysis of factors associated with atheromatosis progression. Of the 289 patients that progressed, 157 (54%) did so in one territory, 75 (26%) in two, 36 (13%) in three, 14 (5%) in four, four (1%) in five, two (0.7%) in six, and one (0.3%) in seven new territories were affected after 24 months. The univariable analysis (Table 2) showed that patients in whom atherosclerosis progressed were significantly older, more frequently smokers, and had higher blood levels of triglycerides, glucose, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, with a higher percentage of patients with diabetes and hypertension. Furthermore, the IMT values and the percentage of patients with plaque at baseline was also higher in progressors.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 481 participants in the NEFRONA cohort study according to plasma fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) concentration

| Characteristic | All (n=481) | Lower Tertile, 3–64 pg/ml (n=160) | Middle Tertile, 65–119 pg/ml (n=160) | Higher Tertile, 120–865 pg/ml (n=161) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 61 (52–68) | 61 (53–68) | 61 (50–68) | 61 (50–68) |

| Men, N (%) | 295 (61) | 107 (67) | 94 (59) | 94 (58) |

| History of smoking, N (%) | 283 (59) | 91 (61) | 88 (55) | 98 (61) |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 336 (70) | 107 (67) | 114 (71) | 115 (71) |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 137 (29) | 43 (27) | 51 (32) | 43 (27) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 442 (92) | 150 (94) | 147 (92) | 145 (90) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 142 (20) | 142 (20) | 142 (20) | 141 (20) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 81 (10) | 81 (11) | 81 (10) | 81 (11) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 180 (156–207) | 179 (148–206) | 184 (165–209) | 180 (157–206) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 104 (85–126) | 102 (75–124) | 106 (93–128) | 104 (87–128) |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 47 (38–59) | 47 (39–58) | 47 (37–61) | 47 (39–61) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 127 (90–171) | 133 (89–171) | 133 (91–180) | 117 (88–164) |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 98 (88–114) | 99 (87–111) | 99 (90–129) | 95 (89–112) |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D, ng/ml | 16.7 (11.9–21.4) | 16.1 (12.0–21.0) | 17.5 (12.2–21.9) | 15.7 (11.1–21.2) |

| Intima-Media Thickness, mm | 0.86 (0.67–1.1) | 0.86 (0.71–1.14) | 0.86 (0.65–1.1) | 0.84 (0.64–1.1) |

| HsCRP, mg/L | 2.12 (1.13–4.52) | 2.12 (1.04–4.52) | 1.97 (1.15–4.36) | 2.16 (1.21–4.73) |

| CKD stage, N (%) | ||||

| 3 | 243 (51) | 58 (36) | 89 (56) | 96 (60) |

| 4–5 | 199 (41) | 71 (44) | 67 (42) | 61 (38) |

| Dialysis | 39 (8) | 31 (20) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Plaque present at baseline, N (%) | 335 (70) | 115 (72) | 106 (66) | 114 (71) |

| FGF-2, pg/ml | 85 (55–138) | 43 (26–55) | 85 (73–100) | 164 (138–204) |

Dyslipidemia: diagnosis of dyslipidemia in the clinical history. Data are median (25th to 75th percentile) for quantitative variables non-normally distributed, mean (SD) for normal variables, and number (percentage) for categorical variables. HsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of 481 participants in the NEFRONA cohort study according to atherosclerosis progression over the subsequent 2 years

| Characteristic | No (n=192) | Yes (n=289) | P (No versus Yes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 56 (42–65) | 63 (56–69) | <0.001 |

| Men, N (%) | 109 (57) | 186 (64) | 0.10 |

| Ever smoker, N (%) | 100 (52) | 183 (63) | 0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 126 (66) | 210 (73) | 0.11 |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 40 (21) | 97 (34) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 171 (89) | 271 (94) | 0.04 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 137 (18) | 145 (21) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 80 (10) | 81 (11) | 0.29 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 179 (156–202) | 183 (157–213) | 0.31 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 102 (85–123) | 105 (86–129) | 0.39 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 48 (40–61) | 47 (37–58) | 0.15 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 109 (82–163) | 137 (103–176) | 0.001 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 95 (86–105) | 102 (91–123) | <0.001 |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D, ng/ml | 17.2 (11.8–22.3) | 16.2 (11.9–20.7) | 0.54 |

| IMT, mm | 0.72 (0.59–1.01) | 0.92 (0.75–1.14) | <0.001 |

| HsCRP, mg/L | 1.87 (1.02–3.77) | 2.49 (1.23–5.17) | 0.01 |

| CKD stage, N (%) | 0.36 | ||

| 3 | 104 (54) | 139 (48) | |

| 4–5 | 72 (38) | 127(44) | |

| Dialysis | 16 (8) | 23 (8) | |

| Plaque presence at baseline, N (%) | 109 (57) | 226 (78) | <0.001 |

Dyslipidemia: diagnosis of dyslipidemia in the clinical history. Data are median (25th to 75th percentile) for quantitative variables non-normally distributed, mean (SD) for normal variables, and number (percentage) for categorical variables. IMT, average intima-media thickness; HsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

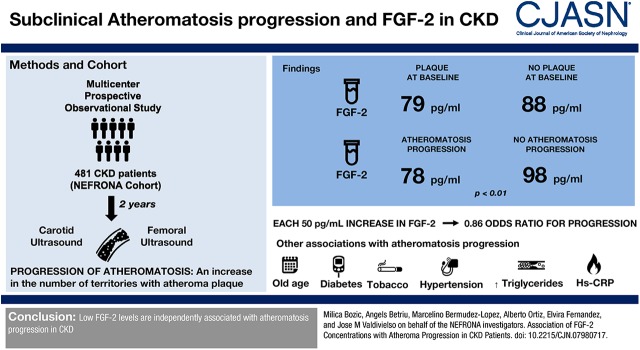

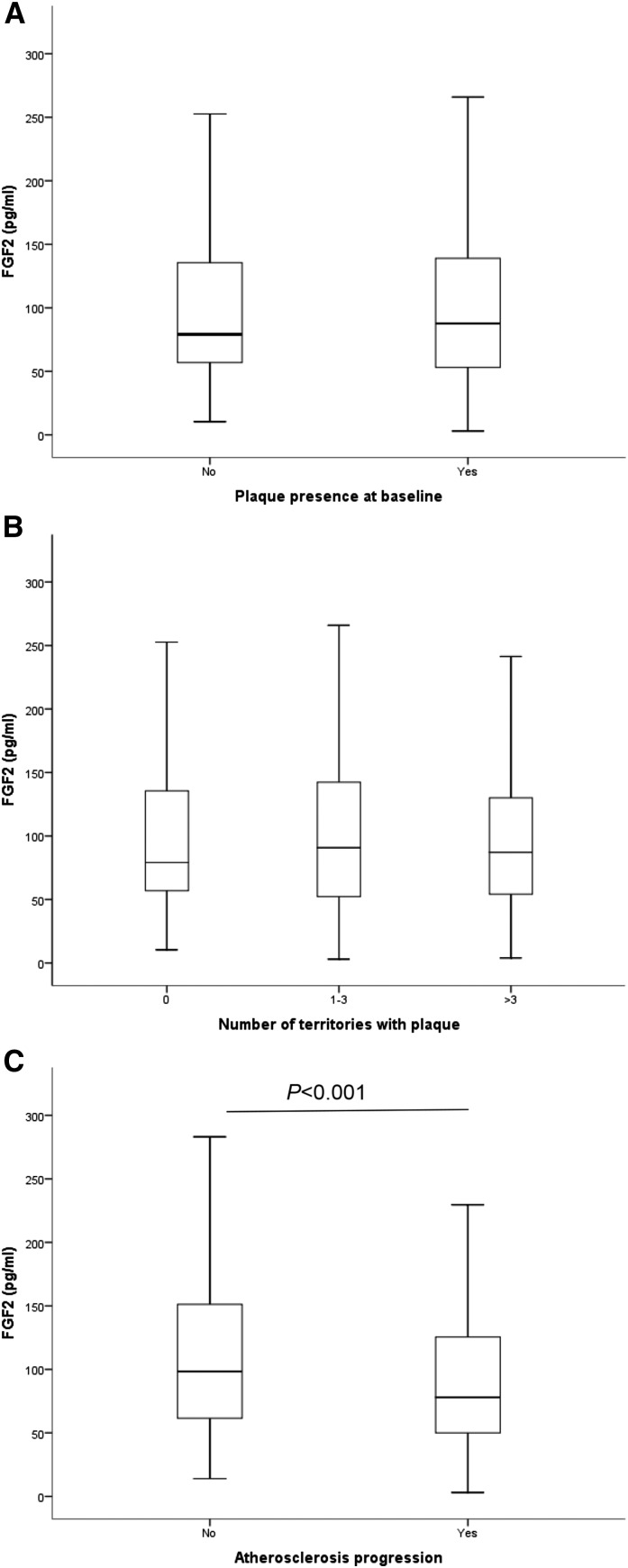

As seen in Figure 1, A and B, FGF-2 levels did not differ among patients with or without plaque at baseline nor between patients with different atheromatosis burden. However, Figure 1C shows that FGF-2 levels were significantly lower in patients in which atherosclerosis progressed after 2 years of follow-up compared with patients where the plaque burden remained stable. In addition, FGF-2 levels were significantly lower in patients with more advanced CKD stages (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Plasma levels of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) are higher in patients with atheromatosis progression after 2 years. (A) Plasma levels in patients with atheromatosis versus no atheromatosis at baseline. (B) Plasma levels in patients with no atheromatosis, mild atheromatosis (one to three territories with plaque), and severe atheromatosis (more than three territories with plaque. (C) Plasma levels in patients in which atheromatosis progressed after 2 years versus those in which it remained stable.

Figure 2.

Plasma levels of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) are lower in patients with more advanced stages of CKD.

The unadjusted analysis modeling atherosclerosis progression (Table 3, model 1) shows that higher levels of FGF-2, assessed as a continuous variable, are associated with lower progression of atherosclerosis. Adjustment for age and sex (model 2) and by several known risk factors for atheromatosis progression (model 3) shows that the effect of FGF-2 remains unmodified. A sensitivity analysis using FGF-2 as a categorical variable (tertiles) yielded similar results. The possible interactions between FGF-2 levels and several parameters (including CKD stage) were tested and disregarded as nonsignificant. The Hosmer and Lemeshow P values show an excellent goodness of fit of the logistic regression model, so the model is considered well calibrated.

Table 3.

Associations of plasma fibroblast growth factor 2 concentration with atherosclerosis progression

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | P Value | Odds Ratio | P Value | Odds Ratio | P Value |

| FGF-2, per 50 pg/ml | 0.86 (0.76–0.96) | 0.008 | 0.85 (0.75–0.95) | <0.01 | 0.86 (0.76–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Hosmer–Lemeshow P value | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.22 | |||

| FGF-2 lowest tertile, 3–64 pg/ml | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| FGF-2 middle tertile, 65–119 pg/ml | 0.61 (0.37–0.99) | 0.05 | 0.65 (0.39–1.01) | 0.11 | 0.70 (0.40–1.20) | 0.20 |

| FGF-2 highest tertile, 120–865 pg/ml | 0.42 (0.26–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.43 (0.26–0.72) | 0.001 | 0.48 (0.28–0.82) | <0.01 |

| Hosmer–Lemeshow P value | 1.00 | 0.19 | 0.69 | |||

First and second rows: model using levels of FGF-2 as a continuous variable. Third to sixth rows: model using levels of FGF-2 as tertiles. Model 1: unadjusted analysis; model 2: adjusted by age and sex; model 3: model 2 plus smoking status, diabetes, dyslipidemia, plaque presence at baseline, stage of CKD, intima-media thickness, body mass index, serum levels of glucose, total cholesterol, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and phosphate. All models included 431 patients (262 progressors and 169 nonprogressors). The lowest tertile of FGF-2 included 143 patients (102 progressors and 41 nonprogressors). The middle tertile of FGF-2 included 143 patients (86 progressors and 47 nonprogressors). The highest tertile of FGF-2 included 145 patients (74 progressors and 71 nonprogressors).

Discussion

This work shows that FGF-2 levels are associated with atherosclerosis progression in patients with CKD. This effect is independent of other parameters known to affect the progression of atherosclerosis in CKD, such as age, the degree of renal function, the levels of cholesterol, and smoking status. Therefore, FGF-2 could be considered as a marker and potential target in atherosclerosis progression in patients with CKD.

The role of FGF-2 in atherosclerosis is unclear, and preclinical data show that beneficial and detrimental effects could coexist. On the one hand, FGF-2 may be deleterious because of its potential to increase plaque size. Thus, FGF-2 and FGF receptors are expressed in VSMC (29) and FGF-2 induces VSMC proliferation in vitro (17). Furthermore, FGF-2 promotes VSMC migration by inducing matrix metalloproteases 2 and 9 expression in baboon aortic explants (30) and by regulating TRAIL expression in mice undergoing the cuff injury model (31). In addition, FGF-2 could regulate VSMC phenotypic transformation from the contractile to the synthetic phenotype, a necessary step in the early stages of atherosclerosis (32). Thus FGF-2 has been shown to act synergistically with PDGF, inducing the phenotypic change in vitro (33). In any case, and although FGF-1 levels increase in atherosclerotic plaques versus normal artery tissue, FGF-2 levels have been reported to remain normal in human atherosclerotic artery samples (29).

On the other hand, the effects of FGF-2 in endothelial cells point to a beneficial effect on atherosclerosis. Atherosclerotic disease is a progressive disorder that develops over a long period of time, triggered locally by endothelial dysfunction. FGF-2 increases proliferation and migration of endothelial cells (34) and furthermore, maintains their integrity (15,35), antagonizing endothelial dysfunction. In addition, administration of FGF-2 improves endothelial function, decreasing vascular endothelial adhesion molecule expression and macrophage infiltration early on in the course of experimental atherosclerosis (36).

In vivo studies in experimental models of atherosclerosis have yielded controversial results. Thus, Che et al. (37) showed that endothelial overexpression of FGF-2 accelerates atherosclerosis in a transgenic mouse model. Raj et al. (38) also showed that pharmacologic inhibition of FGF receptor signaling with a tyrosine kinase activity inhibitor attenuated atherosclerosis in ApoE null mice. However, the effects observed in the former studies could be attributed to signaling of any of the 23 FGF species described so far. In experiments using FGF-2, direct administration of the compound did not increase neointimal formation after balloon injury in pigs (39), dogs (40), and rabbits (41), and it even decreased neointimal formation in a rat model of balloon injury (42) and in a rabbit model of poor distal runoff circulation (43). In any case, the potential different effects of FGF-2 on experimental atherosclerosis could be explained by the different effect of the compound depending on the stage of evolution of plaque, from type 1 plaques with relatively normal histology and endothelial dysfunction, to complicated type 6 plaques with thrombus. Thus, in early stages, increased FGF-2 levels can prevent the formation of plaque by reducing endothelial dysfunction (36). In contrast, in advanced lesions where endothelial dysfunction is no longer an issue, FGF-2 promitogenic actions can induce plaque growth and even rupture by increasing the density of the vasa vasorum and matrix metalloprotease synthesis (44,45). In our study, lower FGF-2 levels are associated with the appearance of new plaques, but were not associated with the baseline presence of atheroma plaques, agreeing with the notion of a protective role for FGF-2 in the early stages of atheroma plaque formation. Indeed, clinical trials using FGF-2 as a treatment for revascularization have not shown any effect aggravating atherosclerotic disease (46,47).

Our results disclosing a higher odds ratio (OR) for atheromatosis progression in patients with CKD stages 4–5 and on dialysis than in patients with CKD stage 3 may appear discordant with those of Rigatto et al. (48) observing lower progression of atheromatosis in later CKD stages. In our study, the OR for atheromatosis progression was higher in patients with CKD stages 4–5 and on dialysis compared with patients with CKD stage 3. However, the design of both studies differ, and those differences may account for the discrepancies. First, our cohort specifically excluded patients with CKD with previous cardiovascular disease, whereas one third of patients in Rigatto’s cohort had a previous cardiovascular event. Furthermore, our study explored the femoral territories, which were not tested in Rigatto’s study. Finally, a possible interaction between FGF-2 levels and CKD stage could also explain the discrepancy, although that interaction was tested and disregarded as nonsignificant.

Another result from our study shows that FGF-2 levels are lower in more severe CKD stages, reaching very low levels in patients on dialysis. There is little information about the role of FGF-2 in CKD. Experimental data show that FGF-2 could be a therapeutic tool to reduce CKD. FGF-2 administration reduces functional and structural damage in experimental CKD (49). Furthermore, FGF-2 mediates the improvement of renal function induced by the administration of mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model of CKD (50). Thus, FGF-2 could have a potential role in the progression of CKD, although further research is warranted.

The main strength of this study is the relatively large number of patients with longitudinal observations, which allows us to make associations controlling for multiple confounders. A second strength is that the vascular exploration was performed by the same team and evaluated by a single reader. Nevertheless, our study also has some limitations. The main one is that out of the total sample of the patients followed for atherosclerosis progression, only a portion had an available plasma sample to measure FGF-2 levels. Therefore, the subpopulation might not be representative of the full cohort, as some parameters differed between patients with an available sample and the rest of the cohort. However, the number of patients is still high enough to adjust for many potential confounding factors. Furthermore, patients that died or suffered a cardiovascular event were also unavailable for the follow-up visit, alongside patients that underwent a kidney transplant. Therefore, we cannot exclude survival bias because individuals with poor cardiovascular health were excluded. Another limitation of the study is the fact that the detection method is a multiplex assay, and results should be validated with a method specific for FGF-2. Furthermore, the observational nature of the study and the unclear biologic function of the measured circulating FGF-2 are additional limitations.

In summary, lower FGF-2 levels are associated with atheromatosis progression in patients with CKD. Further research is needed to determine whether FGF-2 could be a therapeutic target to reduce atheromatosis progression in kidney patients.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Observatory of Atherosclerosis in Nephrology (NEFRONA) team (Eva Castro, Virtudes María, Teresa Molí, Teresa Vidal, Meritxell Soria) and the Biobank of Red de Investigación Renal (REDinREN) for their invaluable support.

This work was supported by the intramural program of the Institut de Recerca Biomedica de Lleida, the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (RETIC RD16/0009/0011, FIS PI16/01354) and Fondos Europeos de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) funds.

The NEFRONA study investigator group is listed in the Supplemental Material.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07980717/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Coll B, Betriu A, Martínez-Alonso M, Borràs M, Craver L, Amoedo ML, Marco MP, Sarró F, Junyent M, Valdivielso JM, Fernández E: Cardiovascular risk factors underestimate atherosclerotic burden in chronic kidney disease: Usefulness of non-invasive tests in cardiovascular assessment. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 3017–3025, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balla S, Nusair MB, Alpert MA: Risk factors for atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease: Recognition and management. Curr Opin Pharmacol 13: 192–199, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olechnowicz-Tietz S, Gluba A, Paradowska A, Banach M, Rysz J: The risk of atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol 45: 1605–1612, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeboah J, Sane DC, Crouse JR, Herrington DM, Bowden DW: Low plasma levels of FGF-2 and PDGF-BB are associated with cardiovascular events in type II diabetes mellitus (diabetes heart study). Dis Markers 23: 173–178, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bozic M, Álvarez Á, de Pablo C, Sanchez-Niño M-D, Ortiz A, Dolcet X, Encinas M, Fernandez E, Valdivielso JM: Impaired vitamin D signaling in endothelial cell leads to an enhanced leukocyte-endothelium interplay: Implications for atherosclerosis development. PLoS One 10: e0136863, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdivielso JM, Coll B, Fernandez E: Vitamin D and the vasculature: Can we teach an old drug new tricks? Expert Opin Ther Targets 13: 29–38, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betriu A, Martinez-Alonso M, Arcidiacono MV, Cannata-Andia J, Pascual J, Valdivielso JM, Fernández E; Investigators from the NEFRONA Study : Prevalence of subclinical atheromatosis and associated risk factors in chronic kidney disease: The NEFRONA study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 1415–1422, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozic M, Panizo S, Sevilla MA, Riera M, Soler MJ, Pascual J, Lopez I, Freixenet M, Fernandez E, Valdivielso JM: High phosphate diet increases arterial blood pressure via a parathyroid hormone mediated increase of renin. J Hypertens 32: 1822–1832, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martín M, Valls J, Betriu A, Fernández E, Valdivielso JM: Association of serum phosphorus with subclinical atherosclerosis in chronic kidney disease. Sex makes a difference. Atherosclerosis 241: 264–270, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gracia M, Betriu À, Martínez-Alonso M, Arroyo D, Abajo M, Fernández E, Valdivielso JM; NEFRONA Investigators : Predictors of subclinical atheromatosis progression over 2 years in patients with different stages of CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 287–296, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson S, James M, Wiebe N, Hemmelgarn B, Manns B, Klarenbach S, Tonelli M; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Cause of death in patients with reduced kidney function. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2504–2511, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shamseddin MK, Parfrey PS: Sudden cardiac death in chronic kidney disease: Epidemiology and prevention. Nat Rev Nephrol 7: 145–154, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benedetto FA, Tripepi G, Mallamaci F, Zoccali C: Rate of atherosclerotic plaque formation predicts cardiovascular events in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 757–763, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nugent MA, Iozzo RV: Fibroblast growth factor-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 32: 115–120, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami M, Nguyen LT, Zhuang ZW, Moodie KL, Carmeliet P, Stan RV, Simons M: The FGF system has a key role in regulating vascular integrity. J Clin Invest 118: 3355–3366, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu MH, Tang ZH, Li GH, Qu SL, Zhang Y, Ren Z, Liu LS, Jiang ZS: Janus-like role of fibroblast growth factor 2 in arteriosclerotic coronary artery disease: Atherogenesis and angiogenesis. Atherosclerosis 229: 10–17, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barillari G, Iovane A, Bonuglia M, Albonici L, Garofano P, Di Campli E, Falchi M, Condò I, Manzari V, Ensoli B: Fibroblast growth factor-2 transiently activates the p53 oncosuppressor protein in human primary vascular smooth muscle cells: Implications for atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis 210: 400–406, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka K, Nagata D, Hirata Y, Tabata Y, Nagai R, Sata M: Augmented angiogenesis in adventitia promotes growth of atherosclerotic plaque in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 215: 366–373, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porcu P, Emanueli C, Desortes E, Marongiu GM, Piredda F, Chao L, Chao J, Madeddu P: Circulating tissue kallikrein levels correlate with severity of carotid atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1104–1110, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junyent M, Martínez M, Borràs M, Coll B, Valdivielso JM, Vidal T, Sarró F, Roig J, Craver L, Fernández E: Predicting cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in chronic kidney disease in Spain. The rationale and design of NEFRONA: A prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol 11: 14, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junyent M, Martínez M, Borrás M, Bertriu A, Coll B, Craver L, Marco MP, Sarró F, Valdivielso JM, Fernández E: [Usefulness of imaging techniques and novel biomarkers in the prediction of cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic kidney disease in Spain: The NEFRONA project]. Nefrologia 30: 119–126, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández-Laso V, Méndez-Barbero N, Valdivielso JM, Betriu A, Fernández E, Egido J, Martín-Ventura JL, Blanco-Colio LM: Soluble TWEAK and atheromatosis progression in patients with chronic kidney disease. Atherosclerosis 260: 130–137, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anguiano L, Riera M, Pascual J, Valdivielso JM, Barrios C, Betriu A, Clotet S, Mojal S, Fernández E, Soler MJ; Investigators from the NEFRONA study : Circulating angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity as a biomarker of silent atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Atherosclerosis 253: 135–143, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arroyo D, Betriu A, Valls J, Gorriz JL, Pallares V, Abajo M, Gracia M, Valdivielso JM, Fernandez E; Investigators from the NEFRONA study : Factors influencing pathological ankle-brachial index values along the chronic kidney disease spectrum: The NEFRONA study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 513–520, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coll B, Betriu A, Martínez-Alonso M, Amoedo ML, Arcidiacono MV, Borras M, Valdivielso JM, Fernández E: Large artery calcification on dialysis patients is located in the intima and related to atherosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 303–310, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, Lonn E, Kendall CB, Mohler ER, Najjar SS, Rembold CM, Post WS; American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force : Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: A consensus statement from the American society of Echocardiography carotid intima-media thickness task force. Endorsed by the society for vascular medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 21: 93, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, Adams H, Amarenco P, Desvarieux M, Ebrahim S, Fatar M, Hernandez Hernandez R, Kownator S, Prati P, Rundek T, Taylor A, Bornstein N, Csiba L, Vicaut E, Woo KS, Zannad F; Advisory Board of the 3rd Watching the Risk Symposium 2004, 13th European Stroke Conference : Mannheim intima-media thickness consensus. Cerebrovasc Dis 18: 346–349, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tattersall MC, Gassett A, Korcarz CE, Gepner AD, Kaufman JD, Liu KJ, Astor BC, Sheppard L, Kronmal RA, Stein JH: Predictors of carotid thickness and plaque progression during a decade: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Stroke 45: 3257–3262, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brogi E, Winkles JA, Underwood R, Clinton SK, Alberts GF, Libby P: Distinct patterns of expression of fibroblast growth factors and their receptors in human atheroma and nonatherosclerotic arteries. Association of acidic FGF with plaque microvessels and macrophages. J Clin Invest 92: 2408–2418, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenagy RD, Hart CE, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Clowes AW: Primate smooth muscle cell migration from aortic explants is mediated by endogenous platelet-derived growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor acting through matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9. Circulation 96: 3555–3560, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan J, Prado-Lourenco L, Khachigian LM, Bennett MR, Di Bartolo BA, Kavurma MM: TRAIL promotes VSMC proliferation and neointima formation in a FGF-2-, Sp1 phosphorylation-, and NFkappaB-dependent manner. Circ Res 106: 1061–1071, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gomez D, Owens GK: Smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 95: 156–164, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen PY, Simons M, Friesel R: FRS2 via fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is required for platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta-mediated regulation of vascular smooth muscle marker gene expression. J Biol Chem 284: 15980–15992, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuboi R, Sato Y, Rifkin DB: Correlation of cell migration, cell invasion, receptor number, proteinase production, and basic fibroblast growth factor levels in endothelial cells. J Cell Biol 110: 511–517, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsunaga S, Okigaki M, Takeda M, Matsui A, Honsho S, Katsume A, Kishita E, Che J, Kurihara T, Adachi Y, Mansukhani A, Kobara M, Matoba S, Tatsumi T, Matsubara H: Endothelium-targeted overexpression of constitutively active FGF receptor induces cardioprotection in mice myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 663–673, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Six I, Mouquet F, Corseaux D, Bordet R, Letourneau T, Vallet B, Dosquet CC, Dupuis B, Jude B, Bertrand ME, Bauters C, Van Belle E: Protective effects of basic fibroblast growth factor in early atherosclerosis. Growth Factors 22: 157–167, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Che J, Okigaki M, Takahashi T, Katsume A, Adachi Y, Yamaguchi S, Matsunaga S, Takeda M, Matsui A, Kishita E, Ikeda K, Yamada H, Matsubara H: Endothelial FGF receptor signaling accelerates atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H154–H161, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raj T, Kanellakis P, Pomilio G, Jennings G, Bobik A, Agrotis A: Inhibition of fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling attenuates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 1845–1851, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Post MJ, Laham RJ, Kuntz RE, Novicki D, Simons M: The effect of intracoronary fibroblast growth factor-2 on restenosis after primary angioplasty or stent placement in a pig model of atherosclerosis. Clin Cardiol 25: 271–278, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lazarous DF, Shou M, Scheinowitz M, Hodge E, Thirumurti V, Kitsiou AN, Stiber JA, Lobo AD, Hunsberger S, Guetta E, Epstein SE, Unger EF: Comparative effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor on coronary collateral development and the arterial response to injury. Circulation 94: 1074–1082, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang C, Yang J, Feng J, Jennings LK: Short-term administration of basic fibroblast growth factor enhances coronary collateral development without exacerbating atherosclerosis and balloon injury-induced vasoproliferation in atherosclerotic rabbits with acute myocardial infarction. J Lab Clin Med 140: 119–125, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rutherford C, Martin W, Salame M, Carrier M, Anggård E, Ferns G: Substantial inhibition of neo-intimal response to balloon injury in the rat carotid artery using a combination of antibodies to platelet-derived growth factor-BB and basic fibroblast growth factor. Atherosclerosis 130: 45–51, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shoji T, Yonemitsu Y, Komori K, Tanii M, Itoh H, Sata S, et al. : Intramuscular gene transfer of FGF-2 attenuates endothelial dysfunction and inhibits intimal hyperplasia of vein grafts in poor-runoff limbs of rabbit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H173–H182, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sigala F, Savvari P, Liontos M, Sigalas P, Pateras IS, Papalampros A, Basdra EK, Kolettas E, Papavassiliou AG, Gorgoulis VG: Increased expression of bFGF is associated with carotid atherosclerotic plaques instability engaging the NF-κB pathway. J Cell Mol Med 14: 2273–2280, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mollmark JI, Park AJ, Kim J, Wang TZ, Katzenell S, Shipman SL, Zagorchev LG, Simons M, Mulligan-Kehoe MJ: Fibroblast growth factor-2 is required for vasa vasorum plexus stability in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 2644–2651, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumagai M, Marui A, Tabata Y, Takeda T, Yamamoto M, Yonezawa A, Tanaka S, Yanagi S, Ito-Ihara T, Ikeda T, Murayama T, Teramukai S, Katsura T, Matsubara K, Kawakami K, Yokode M, Shimizu A, Sakata R: Safety and efficacy of sustained release of basic fibroblast growth factor using gelatin hydrogel in patients with critical limb ischemia. Heart Vessels 31: 713–721, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lederman RJ, Mendelsohn FO, Anderson RD, Saucedo JF, Tenaglia AN, Hermiller JB, Hillegass WB, Rocha-Singh K, Moon TE, Whitehouse MJ, Annex BH; TRAFFIC Investigators : Therapeutic angiogenesis with recombinant fibroblast growth factor-2 for intermittent claudication (the TRAFFIC study): A randomised trial. Lancet 359: 2053–2058, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rigatto C, Levin A, House AA, Barrett B, Carlisle E, Fine A: Atheroma progression in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 291–298, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villanueva S, Contreras F, Tapia A, Carreño JE, Vergara C, Ewertz E, Cespedes C, Irarrazabal C, Sandoval M, Velarde V, Vio CP: Basic fibroblast growth factor reduces functional and structural damage in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F430–F441, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villanueva S, Ewertz E, Carrión F, Tapia A, Vergara C, Céspedes C, Sáez PJ, Luz P, Irarrázabal C, Carreño JE, Figueroa F, Vio CP: Mesenchymal stem cell injection ameliorates chronic renal failure in a rat model. Clin Sci (Lond) 121: 489–499, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.