Low urinary ammonium (NH4+) excretion is a risk factor for kidney failure and death in CKD (1). Few clinical laboratories measure urine NH4+, limiting clinical application. The urinary anion gap (UAG) and urine osmolal gap (UOG) have been used to estimate urine NH4+. Unfortunately, the UAG had a poor correlation with NH4+ in CKD unless urine sulfate and phosphate were included in the calculation (2). Thus, unmeasured anions significantly affect UAG’s performance as an NH4+ surrogate. Less is known about the utility of the UOG as an NH4+ surrogate. The UOG is determined by subtracting the calculated urine osmolality (OsmCALC)—determined from concentrations of urine Na+, K+, urea nitrogen, and glucose—from the measured urine osmolality (OsmMEAS). A parallel problem could occur for the UOG as with UAG because of unmeasured cations such as magnesium and calcium, as considerable interindividual differences in these cations have been observed (3,4). The UOG has been reported to have strong correlation with NH4+ in persons with diabetic ketoacidosis, in patients with CKD both with and without metabolic acidosis (MA), and in healthy individuals without MA (5,6). However, others have reported poor agreement between UOG and NH4+ (7). Crude inspection of data from these studies revealed that 10%–20% of individuals had a negative UOG (5–7), which is troublesome as the UOG conceptually represents unmeasured osmoles and should theoretically always have positive values. The negative UOG might be because the OsmCALC assumes that Na+ and K+ are completely dissociated from their accompanying anions in urine, which may be incorrect because the osmotic coefficient (ϕ) of molecules such as NaCl are influenced by the osmolality of, and other constituents in the solution (8,9). If incompletely dissociated, doubling Na+ and K+ will overestimate their contributions to the urine osmolality, which may also render the UOG as a poor NH4+ surrogate.

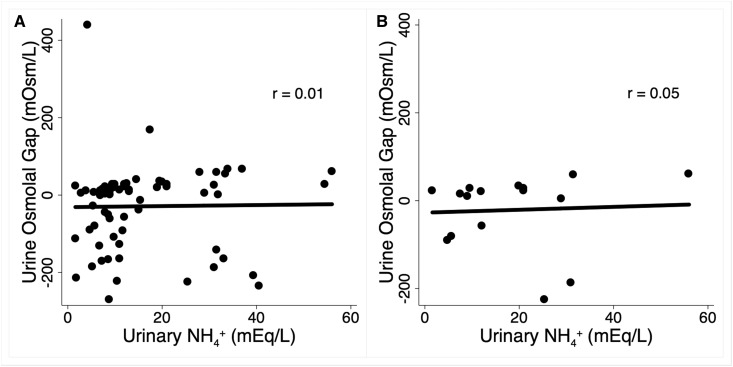

We determined the correlation between urine NH4+ and UOG in 70 overnight urine collections (range, 6–12 hours) obtained from 28 kidney transplant recipients in a randomized study to determine the effect of sodium bicarbonate on kidney injury markers (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01225796). Up to three collections were obtained from each individual over 6 months. OsmCALC was determined using the equation [2(Na++K+ (mEq/L))+ urea nitrogen (mg/dl)/2.8+ glucose (mg/dl)/18]. UOG was calculated by subtracting OsmCALC from OsmMEAS (5); the latter was determined by freezing point depression. Urine NH4+ was measured by the formalin titration method (10). The mean (SD) age of the study sample was 48 (14) years, 16 (57%) were women, and 27 (96%) were white. Mean (SD) eGFR was 68 (16) ml/min per 1.73 m2. Sixteen measurements were performed in the setting of MA (serum bicarbonate <22 mEq/L). Table 1 shows laboratory data for the entire sample and the MA subset. In the entire sample, the mean (SD) UOG was −29 (109) mOsm/L and 28 (40%) had a negative UOG. In the MA subset, five out of 16 (31%) had a negative UOG and the mean (SD) UOG was −21 (85) mOsm/L. There was no correlation between UOG and urine NH4+ concentration in the entire cohort, in the MA subset (Figure 1), or in the 16 measurements performed at baseline (r=−0.05), before treatment with sodium bicarbonate.

Table 1.

Serum and urine laboratory characteristics among study participants

| Laboratory Data | All Measurements, n=70 | Metabolic Acidosis, n=16 |

|---|---|---|

| Serum, mEq/L | ||

| Sodium | 139 (3) | 139 (2) |

| Potassium | 4.3 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.4) |

| Chloride | 105 (3) | 107 (2) |

| Bicarbonate | 23 (3) | 20 (1) |

| Urine | ||

| Ammonium, mEq/L | 16 (12) | 19 (14) |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 78 (43) | 80 (46) |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 21 (14) | 19 (13) |

| Urea nitrogen, mg/dl | 535 (369) | 572 (355) |

| Glucose, mg/dla | 103 (205) | 29 (62) |

| Measured osmolality, mOsm/kg | 361 (234) | 382 (245) |

| Calculated osmolality, mOsm/L | 390 (229) | 403 (232) |

| Osmolal gap, mOsm/L | −29 (109) | −21 (85) |

Data are presented as mean (SD).

Shown are the mean (SD) glucose concentrations for samples in which glucose was detected; n=19 for all measurements and n=7 for metabolic acidosis.

Figure 1.

Urine osmolal gap is a poor estimate of urine NH4+ concentration. Urinary ammonium versus urine osmolal gap in (A) all measurements (n=70) and (B) the subset with metabolic acidosis (n=16). NH4+, ammonium.

We posit that the poor correlation between UOG and NH4+ may be because Na+ and K+ incompletely dissociate from their accompanying anions in urine. Therefore, doubling Na+ and K+ overestimated their contributions to the urine osmolality, as evidenced by a negative UOG in 40% overall and in one third with MA in our sample, resulting in an UOG that unreliably estimates unmeasured osmoles, including NH4+. In NaCl solutions with osmolality in the physiologic range of serum, the ϕ of NaCl is 0.93, indicating that 7% of Na+ is not dissociated from Cl− (8,9). Furthermore, the ϕ of NaCl decreases with increasing osmolality (ϕ=0.91 at 600 mOsm/kg) and is affected by other constituents in the solution (8). In fluids with many solutes and a wide range of osmolalities, such as urine, the dissociation of Na+ and K+ from their accompanying anions is unlikely to be complete and is difficult to predict. With respect to calculating serum osmolality, doubling Na+ works reasonably well because the ϕ of 0.93 is partly offset by the water content of plasma, which is 93% (9). Including unmeasured urinary cations such as calcium and magnesium would raise OsmCALC, resulting in an even lower UOG. Hence, excluding urinary cations is not the main reason why the UOG unreliably estimated NH4+ in our sample.

The poor correlation between UOG and NH4+ shown here is different from some prior studies, and we observed a higher proportion with a negative UOG (5,6); the reasons for these findings are unclear. We do not think that the discrepancy is related to kidney transplantation, as a negative UOG has been observed in healthy individuals and in CKD (5,6). In another study evaluating the correlation between OsmCALC and OsmMEAS in five European cohorts, a large proportion of individuals had OsmCALC higher than OsmMEAS. For example, mean OsmCALC was 7 mOsm/L higher than mean OsmMEAS in the largest cohort (n=2305) (11). Hence, the large proportion with a higher OsmCALC than OsmMEAS is not unique to our study, and supports the notion that the difference between OsmCALC and OsmMEAS is an unreliable estimate of unmeasured osmoles, including NH4+.

In summary, we found no correlation between UOG and NH4+. We believe this is because of an incorrect assumption that Na+ and K+ completely dissociate from their accompanying anions in urine. These factors render the UOG an unreliable estimate of unmeasured urinary osmoles, including NH4+.

This study was approved and overseen by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah and was performed under the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki. The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul as outlined in the “Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism.”

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Kidney Foundation of Utah and Idaho.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Raphael KL, Carroll DJ, Murray J, Greene T, Beddhu S: Urine ammonium predicts clinical outcomes in Hypertensive kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2483–2490, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raphael KL, Gilligan S, Ix JH: Urine anion gap to predict urine ammonium and related outcomes in kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 205–212, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welles CC, Schafer AL, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG, Whooley MA, Ix JH: Urine calcium excretion, cardiovascular events, and mortality in outpatients with stable coronary artery disease (from the Heart and Soul study). Am J Cardiol 110: 1729–1734, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joosten MM, Gansevoort RT, Mukamal KJ, van der Harst P, Geleijnse JM, Feskens EJ, Navis G, Bakker SJ; PREVEND Study Group: Urinary and plasma magnesium and risk of ischemic heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr 97: 1299–1306, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyck RF, Asthana S, Kalra J, West ML, Massey KL: A modification of the urine osmolal gap: An improved method for estimating urine ammonium. Am J Nephrol 10: 359–362, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirschbaum B, Sica D, Anderson FP: Urine electrolytes and the urine anion and osmolar gaps. J Lab Clin Med 133: 597–604, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meregalli P, Luthy C, Oetliker OH, Bianchetti MG: Modified urine osmolal gap: An accurate method for estimating the urinary ammonium concentration? Nephron 69: 98–101, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stadie WC, Sunderman FW: The osmotic coefficient of sodium in sodium hemoglobinate and of sodium chloride in hemoglobin solution. J Biol Chem 91: 227–241, 1931 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gennari FJ: Current concepts. Serum osmolality. Uses and limitations. N Engl J Med 310: 102–105, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunarro JA, Weiner MW: A comparison of methods for measuring urinary ammonium. Kidney Int 5: 303–305, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youhanna S, Bankir L, Jungers P, Porteous D, Polasek O, Bochud M, Hayward C, Devuyst O: Validation of surrogates of urine osmolality in population studies. Am J Nephrol 46: 26–36, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]