Abstract

Background and objectives

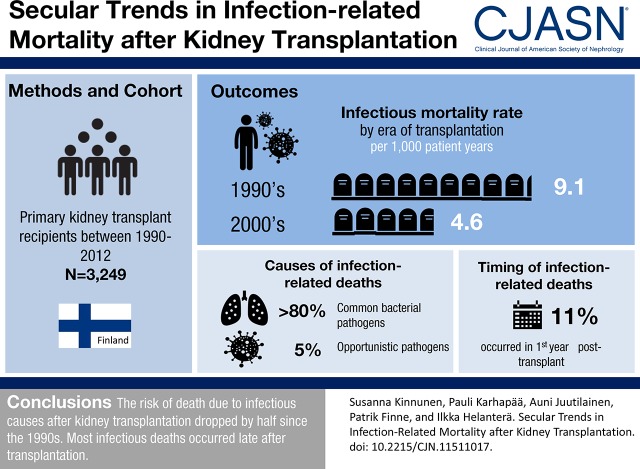

Infections are the most common noncardiovascular causes of death after kidney transplantation. We analyzed the current infection-related mortality among kidney transplant recipients in a nationwide cohort in Finland.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Altogether, 3249 adult recipients of a first kidney transplant from 1990 to 2012 were included. Infectious causes of death were analyzed, and the mortality rates for infections were compared between two eras (1990–1999 and 2000–2012). Risk factors for infectious deaths were analyzed with Cox regression and competing risk analyses.

Results

Altogether, 953 patients (29%) died during the follow-up, with 204 infection-related deaths. Mortality rate (per 1000 patient-years) due to infections was lower in the more recent cohort (4.6; 95% confidence interval, 3.5 to 6.1) compared with the older cohort (9.1; 95% confidence interval, 7.6 to 10.7); the incidence rate ratio of infectious mortality was 0.51 (95% confidence interval, 0.30 to 0.68). The main causes of infectious deaths were common bacterial infections: septicemia in 38% and pulmonary infections in 45%. Viral and fungal infections caused only 2% and 3% of infectious deaths, respectively (such as individual patients with Cytomegalovirus pneumonia, Herpes simplex virus meningoencephalitis, Varicella zoster virus encephalitis, and Pneumocystis jirovecii infection). Similarly, opportunistic bacterial infections rarely caused death; only one death was caused by Listeria monocytogenes, and two were caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Only 23 (11%) of infection-related deaths occurred during the first post-transplant year. Older recipient age, higher plasma creatinine concentration at the end of the first post-transplant year, diabetes as a cause of ESKD, longer pretransplant dialysis duration, acute rejection, low albumin level, and earlier era of transplantation were associated with increased risk of infectious death in multivariable analysis.

Conclusions

The risk of death due to infectious causes after kidney transplantation in Finland dropped by one half since the 1990s. Common bacterial infections remained the most frequent cause of infection-related mortality, whereas opportunistic viral, fungal, or unconventional bacterial infections rarely caused deaths after kidney transplantation.

Keywords: kidney transplantation; mortality risk; infections; risk factors; Pneumocystis carinii; Cause of Death; Listeria monocytogenes; Mycobacterium tuberculosis; creatinine; cytomegalovirus; Herpesvirus 3, Human; Fungal Viruses; Follow-Up Studies; Incidence; Finland; Sepsis; Bacterial Infections; Mycoses; Pneumonia; Meningoencephalitis; Encephalitis; Albumins; diabetes mellitus; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Simplexvirus

Introduction

Patient survival after kidney transplantation has improved markedly during the past decades (1,2). The frequency of acute rejection has decreased, whereas infectious concerns have increased, and infections remain the most common noncardiovascular causes of death after kidney transplantation, accounting for approximately 15%–20% of deaths (3–5).

Because of improved diagnostic tools and antiviral agents, common opportunistic viruses, such as Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and BK polyomavirus, rarely cause life-threatening infections or graft losses (6,7). However, new infectious threats have emerged, such as influenza, especially influenza A (H1N1) (8), and currently, deaths from bacterial infections predominate the infectious causes of deaths after kidney transplantation (9).

Despite being highly increased after kidney transplantation, little is known about the current infection-related mortality after kidney transplantation, especially about the specific infectious causes of death.

The aim of this study is to present current nationwide data on infection-related mortality among kidney transplant recipients in a modern developed country. We furthermore looked into the risk factors for infection-related mortality and specific causes of deaths and evaluated whether these have changed during the past decades.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

All adult recipients of a primary kidney transplantation between 1990 and 2012 (n=3249) in Finland were included in this observational inception cohort study. Between 1990 and 2012, altogether, 41 patients received a combined transplant (11 pancreas-kidney and 30 liver-kidney transplants) and were included in the analyses. Data were retrieved from the Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases, which has been estimated to cover 97%–99% of all patients accepted for RRT (RRT, dialysis, or kidney transplantation) in Finland since 1965. All patients have provided written informed consent and permission to use the data anonymously in registry reports and for research purposes. The following data were obtained from the registry for all patients at the start of RRT: age, sex, cause of ESKD as International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) codes, date of start of first RRT, initial and last modality of RRT before transplantation (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis), date of first kidney transplantation, date of return to dialysis after transplantation, date of death (also after transplantation), and cause of death. Primary kidney disease was categorized as GN, polycystic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus type 1 or type 2, pyelonephritis, amyloidosis, nephrosclerosis, miscellaneous, or unknown. Data on body mass index, laboratory data from the end of the year before transplantation and the end of the first year after transplantation, and data about immunosuppression were available since 1992. Patients with missing data were excluded from the analyses. For laboratory data and body mass index, sensitivity analyses were performed including patients with the data available. Data about creatinine were missing for 288 patients, and data about plasma albumin were missing for 678 patients. Patients with missing data were excluded from the analyses. In addition, to address potential sources of bias, data about acute rejections and induction therapy were retrieved from the Finnish Transplant Registry, and sensitivity analyses were performed including these data.

Causes of death are reported to the Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases by the treating nephrologist. The statistics on mortality in Finland are on the basis of death certificates, in which ICD codes for the cause of death are assigned by the physician who treated the deceased during the final illness. In addition, all death certificates in Finland are submitted for verification to a forensic medicine specialist in the competent authority, and after approval, they are sent to the official National Death Register at Statistics Finland.

If the cause of death was not reported to the Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases, it was acquired from Statistics Finland on the basis of the individual social security code. Since 1996, causes of death statistics have been compiled according to ICD-10. Before 1996, ICD-9 was used, and these data were converted to ICD-10. There were no missing causes of death.

Causes of death were grouped into four categories: infection, cardiovascular, malignancy, and other. Causes of infection-related deaths were classified into seven categories: bacterial or unspecified septicemia (ICD-10 codes A04.7–A49.9), pulmonary infection defined as bacterial or unspecified pneumonia (J13–J16, J18–J20, J40, and J69) or empyema/pleural effusion, specified viral infection (B25.0, G05.1, and J17.1), specified fungal infection (B37.7, B59, and J17.2), gastroenterologic infection (K65–K81), tuberculosis (A15.9), and other infection (I33.0, G00.8, I52.0*A39.5, L03.1, N39.0 M86.1, and T87.4).

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons between the groups were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. Nonparametric statistics were applied, because all distributions were not normal. Survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with death as the event, and patients were censored at the end of the follow-up. Cause-specific mortality rates were reported per 1000 patient-years and calculated separately for deaths due to infections, cardiovascular causes, malignancies, and other causes. Incidence rate ratios were calculated to compare mortality in patients transplanted during the two different eras; 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated according to the Poisson Exact method.

Cox regression models were used to identify risk factors for infection-related mortality, such as age at transplantation, sex, cause of ESKD, era of transplantation, initial modality of pretransplant dialysis, dialysis duration before transplantation, and immunosuppressive therapy. Cause of ESKD was categorized as GN, polycystic kidney disease, diabetes (including both type 1 and type 2 diabetes), and other. Variables that were significant in the univariable model (<0.05) were selected to multivariable models. Cumulative incidence of death due to infectious causes was calculated using a competing risk method that takes deaths due to other causes into account as competing risk events. As an alternative to Cox regression, relative risks of death due to infection were also estimated, fitting a proportional subdistribution hazards regression model that takes deaths due to other causes into account as competing risk events (10,11). First degree interactions between all of the exposure variables were analyzed, and all statistically significant interactions are reported. For statistical analyses, we used IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0) and the R statistical software 2.14.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org). Two-sided P values >0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

A total of 3249 adult patients (age ≥18 years old) received their first kidney transplantation in Finland between 1990 and 2012: 1283 during 1990–1999 and 1966 during 2000–2012. The patients were followed for a maximum of 22 years from the day of first transplantation to death (n=953; also after graft loss), the end of the follow-up period on December 31, 2012, or loss to follow-up (n=12). The median follow-up time was 14.1 years for patients transplanted during 1990–1999 and 5.7 years for patients transplanted in 2000–2012.

Patients included in the study are described in Table 1. Compared with the patients transplanted during 1990–1999, the patients transplanted during 2000–2012 were significantly older, more often had type 2 diabetes as the cause of ESKD, were less frequently on peritoneal dialysis, and had longer duration of dialysis before transplantation. There were significant differences in the immunosuppressive regimen between the two decades, because tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were not available during the earlier era. During the recent era, all patients with data available on immunosuppression received either cyclosporin- or tacrolimus-based immunosuppression at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of first kidney transplant recipients enrolled in the Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases (n=3249)

| Variables | All | 1990–1999, n=1283 | 2000–2012, n=1966 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (%) | 2041 (63) | 778 (61) | 1263 (64) |

| Age at transplantation, yr | 49±13 | 45±12 | 51±13 |

| Age group at transplantation (%) | |||

| 18–44 yr | 1233 (38) | 606 (47) | 627 (32) |

| 45–65 yr | 1690 (52) | 606 (47) | 1084 (55) |

| Over 65 yr | 326 (10) | 71 (6) | 255 (13) |

| Treatment before transplantation (%) | |||

| Hemodialysis | 1936 (60) | 716 (56) | 1220 (62) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 1300 (40) | 562 (44) | 738 (38) |

| Preemptive | 13 (0.4) | 5 (0.4) | 8 (0.4) |

| Time on dialysis before transplantation, yr | 1.8±1.6 | 1.4±1.3 | 2.1±1.7 |

| Cause of ESKD (%) | |||

| GN | 769 (24) | 343 (27) | 426 (22) |

| Polycystic disease | 591 (18) | 208 (16) | 383 (20) |

| Diabetes type 1 | 786 (24) | 327 (26) | 459 (23) |

| Diabetes type 2 | 143 (5) | 25 (2) | 118 (6) |

| Chronic pyelonephritis | 214 (7) | 107 (8) | 107 (5) |

| Amyloidosis | 76 (2) | 40 (3) | 36 (2) |

| Nephrosclerosis | 101 (3) | 39 (3) | 62 (3) |

| Other | 366 (11) | 147 (11) | 219 (11) |

| Unknown | 203 (6) | 47 (4) | 156 (8) |

| Immunosuppression (%) | |||

| Cyclosporin | 906 (71) | 1452 (74) | |

| Tacrolimus | 0 | 407 (21) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 94 (7) | 1524 (78) | |

| Steroid | 963 (75) | 1697 (86) | |

| Azathioprine | 806 (63) | 201 (10) | |

| Missing | 308 (24) | 98 (5) |

Mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

Mortality by Cause of Death

Nine hundred fifty-three (29%) patients died during the follow-up; 204 patients (21% of all deceased patients) died due to infections, 442 (48%) died due to cardiovascular causes, 129 (13%) died due to malignancies, and 178 (19%) died from other causes. During the most recent versus the earlier cohort, the causes of death were infectious in 18% versus 23%, cardiovascular disease in 48% versus 45%, and malignancy in 16% versus 12%, respectively. Altogether, 710 (76% of all deceased patients) patients died with a functioning graft.

The overall patient survival in the whole study population was 97% at 1 year, 89% at 5 years, and 73% at 10 years after transplantation.

Mortality rates due to infections, cardiovascular causes, and malignancies were lower in the recent cohort (Table 2). The mortality rates (per 1000 patient-years) due to infections were 4.6 and 9.1 for patients transplanted in 2000–2012 and 1990–1999, respectively, with a mortality rate ratio of 0.51. The mortality rate ratios were 0.67 for cardiovascular disease mortality and 0.80 for mortality due to malignancies.

Table 2.

Mortality rates (deaths per 1000 patient-years) and mortality rate ratios from all causes, cardiovascular causes, malignancy, and infections in first kidney transplant recipients in Finland segregated by the era of transplantation

| Cause of Mortality | 1990–1999 | 2000–2012 | IRR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cause | ||||

| Rate (95% CI) | 39.8 (37.0 to 43.1) | 24.9 (22.2 to 28.0) | 0.63 | 0.55 to 0.72 |

| n | 666 | 287 | ||

| Infection | ||||

| Rate (95% CI) | 9.1 (7.6 to 10.7) | 4.6 (3.0 to 5.4) | 0.51 | 0.30 to 0.68 |

| n | 151 | 53 | ||

| 1-yr Infectious mortality | ||||

| Rate (95% CI) | 12.8 (7.81 to 20.98) | 3.7 (1.78 to 7.86) | 0.29 | 0.12 to 0.71 |

| n | 16 | 7 | ||

| Cardiovascular | ||||

| Rate (95% CI) | 18.2 (16.0 to 20.7) | 12.1 (10.2 to 14.4) | 0.67 | 0.56 to 0.76 |

| n | 303 | 139 | ||

| Malignancy | ||||

| Rate (95% CI) | 5.0 (4.0 to 6.2) | 4.0 (3.0 to 5.4) | 0.80 | 0.63 to 0.95 |

| n | 83 | 46 |

IRR, incidence rate ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Infection-Related Mortality and Its Causes

A total of 204 (21% of all deaths) infection-related deaths occurred during the follow-up, of which 147 (72%) were in patients with a functioning graft. Cumulative incidence of infection-related death was lower in 2000–2012 than in 1990–1999 (Figure 1). During both eras, the most frequent causes of infectious death were common bacterial infections: pulmonary infection in 45% (36% versus 49% in 2000–2012 versus 1990–1999, respectively) and septicemia in 38% (42% versus 37% in 2000–2012 versus 1990–1999, respectively) of the patients (Supplemental Table 1, Table 3).

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of infectious death was lower in patients transplanted between 2000–2012 compared to 1990–1999. Continuous line: years 1990–1999; dotted line: years 2000–2012.

Table 3.

Infectious causes of death after kidney transplantation among first kidney transplant recipients enrolled in the Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases (n=3249)

| Type of Infection (%) | All, n=204 | 1990–1999, n=151 | 2000–2012, n=53 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary infection | 92 (45) | 73 (48) | 19 (36) |

| Septicemia | 78 (38) | 56 (37) | 22 (42) |

| Gastroenteric infection | 12 (6) | 9 (6) | 3 (6) |

| Fungal infection | 6 (3) | 3 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Viral infection | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (6) |

| Tuberculosis | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 10 (5) | 8 (5) | 2 (3) |

Bacteremia caused 78 deaths, of which 31 (40%) were described as unspecified septicemia, whereas the causative pathogen was known in 43 (55%) of the deaths. Staphylococcus aureus accounted for 11 of the bacteremia deaths, and unspecified Gram-negative sepsis accounted for eight of the bacteremia deaths, whereas there were only individual deaths from Meningococceal and Streptococcal septicemia. Invasive viral or fungal infections made up 2% and 3% of all infectious deaths, respectively. Only individual deaths from fatal CMV pneumonia, Herpes simplex virus meningoencephalitis, Varicella zoster virus encephalitis, and Pneumocystis jirovecii infection occurred. Opportunistic bacterial infections rarely caused death; only one death was caused by Listeria monocytogenes. Two deaths were caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Mortality within the First Year after Kidney Transplantation

Of all deaths, 83 (9%) occurred within the first year after transplantation. The causes of death were cardiovascular in 59% versus 49%, infection in 21% versus 33%, and malignancy in 6% versus 10% during the recent versus the earlier cohort, respectively. During the first year after transplantation, mortality rate due to infections was significantly lower in 2000–2012 (3.7 per 1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 1.8 to 7.9) than in 1990–1999 (12.8 per 1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 7.8 to 21.0), with a mortality rate ratio of 0.29 (95% CI, 0.12 to 0.71).

Of the 23 infection-related deaths that occurred during the first year after transplantation, the cause was septicemia in 44% and pulmonary infection in 30%. There was only one CMV-related death, and there were individual deaths from Herpes simplex virus meningoencephalitis and viral pneumonia during the first year after transplantation.

Infection-Related Mortality Risk Factors

Older age was the strongest predictor of infection-related mortality. When adjusting for age and sex, earlier era of transplantation (hazard ratio [HR], 1.78; 95% CI, 1.25 to 2.53), diabetes as the cause of ESKD (HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.21 to 2.62), and dialysis duration for >2 years before transplantation (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.25) were associated with infection-related death (Table 4).

Table 4.

Risk factors for infectious death among first kidney transplant recipients enrolled in the Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases: All patients, n=3249

| Variable | Adjusteda HR (95% CI): Age and Sex | Adjustedb HR (95% CI) | No. of Infectious Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age per 1-yr increment | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.07), P<0.001 | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.08), P<0.001 | 204 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1.20 (0.90 to 1.59) | 1.13 (0.85 to 1.52) | 131 |

| Women | 1 | 1 | 73 |

| Era of transplantation | |||

| 1990–1999 | 1.78 (1.25 to 2.53), P=0.002 | 2.07 (1.44 to 2.98), P<0.001 | 151 |

| 2000–2012 | 1 | 1 | 53 |

| Cause of ESKD | |||

| GN | 1 | 1 | 52 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 0.78 (0.51 to 1.20) | 0.83 (0.54 to 1.28) | 36 |

| Diabetes | 1.78 (1.21 to 2.62), P=0.003 | 1.89 (1.28 to 2.79), P=0.001 | 60 |

| Other | 0.90 (0.61 to 1.31) | 0.90 (0.61 to 1.32) | 56 |

| Pretransplant dialysis duration, mo | |||

| 0–12 | 1 | 1 | 72 |

| 12–24 | 1.39 (1.00 to 1.94), P=0.05 | 1.41 (1.01 to 1.97), P=0.04 | 70 |

| >24 | 1.59 (1.12 to 2.25), P<0.01 | 1.75 (1.23 to 2.50), P=0.002 | 62 |

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Adjusted for patient age and sex.

Adjusted for patient age, sex, era of transplantation, cause of ESKD, and dialysis duration.

Laboratory data from the end of the calendar year of the transplantation were available on plasma creatinine for 91% of the patients and plasma albumin for 79% of the patients. When adjustment was made for age and sex, higher plasma creatinine (HR, 1.00 per 1-μmol/L increment; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.00; P=0.002) and plasma albumin level below 36 g/L (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.23; P<0.01) were associated with risk of infection-related mortality.

During the recent era, the risk of death from infection was almost twofold in men, whereas this was not the case in the earlier era (Tables 5 and 6). The association of diabetes as the cause of ESKD or pretransplant dialysis duration with infection-related mortality lost statistical significance during the recent era, but no interaction was observed between diabetes or dialysis duration and era with respect the risk of infectious death (P=0.18).

Table 5.

Risk factors for infectious death among first kidney transplant recipients enrolled in the Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases: Patients transplanted 1990–1999 (n=1283)

| Variable | Adjusteda RR (95% CI): Age and Sex | Adjustedb RR (95% CI) | No. of Infectious Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age per 1-yr increment | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.06), P<0.001 | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.08), P<0.001 | 151 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1.05 (0.76 to 1.45) | 1.0 (0.72 to 1.39) | 91 |

| Women | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| Cause of ESKD | |||

| GN | 1 | 1 | 40 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 0.81 (0.49 to 1.33) | 0.85 (0.51 to 1.40) | 26 |

| Diabetes | 2.01 (1.29 to 3.14), P=0.002 | 2.03 (1.30 to 3.18), P=0.002 | 46 |

| Other | 0.86 (0.55 to 1.35) | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.30) | 39 |

| Pretransplant dialysis duration, mo | |||

| 0–12 | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| 12–24 | 1.57 (1.08 to 2.27), P=0.02 | 1.51 (1.04 to 2.19), P=0.03 | 53 |

| >24 | 1.80 (1.08 to 2.99), P=0.004 | 1.90 (1.26 to 2.87), P=0.002 | 38 |

RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Adjusted for patient age and sex.

Adjusted for patient age, sex, cause of ESKD, and dialysis duration.

Table 6.

Risk factors for infectious death among first kidney transplant recipients enrolled in the Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases: Patients transplanted 2000–2012 (n=1966)

| Variable | Adjusteda RR (95% CI): Age and Sex | Adjustedb RR(95% CI) | No. of Infectious Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age per 1-yr increment | 1.10 (1.07 to 1.135), P<0.001 | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.14), P<0.001 | 53 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1.92 (1.03 to 3.60), P=0.04 | 1.81 (0.96 to 3.41), P=0.68 | 40 |

| Women | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| Cause of ESKD | |||

| GN | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 0.86 (0.37 to 2.00) | 0.85 (0.37 to 2.00) | 10 |

| Diabetes | 1.64 (0.74 to 3.62), P=0.22 | 1.58 (0.71 to 3.51) | 14 |

| Other | 1.04 (0.49 to 2.2) | 1.02 (0.48 to 2.14) | 17 |

| Pretransplant dialysis duration, mo | |||

| 0–12 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| 12–24 | 1.09 (0.52 to 2.30) | 1.03 (0.49 to 2.17) | 17 |

| >24 | 1.38 (0.68 to 2.79) | 1.28 (0.62 to 2.62) | 24 |

RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Adjusted for patient age and sex.

Adjusted for patient age, sex, cause of ESKD, and dialysis duration.

Sensitivity Analyses

A separate analysis that included as events only infection-related deaths of patients with a functioning graft showed similar HRs for the risk factors as in Tables 4–6 (Supplemental Table 2).

As an alternative method of analysis, competing risk models were built on the whole study population using death due to infection as the primary outcome and death resulting from cardiovascular causes, malignancies, and other causes as competing risk events. These models showed no important differences compared with the Cox regression models presented in Tables 4–6 (Supplemental Table 3).

Data about acute rejections or induction immunosuppression were available for 88% of the patients transplanted between 1990 and 2012. Frequency of acute rejection was 13% among patients transplanted in 2000–2012 versus 23% among patients transplanted in 1990–1999 (P<0.001). When included in the Cox regression model analyzing the risk of infectious mortality (adjusted for patient age, sex, era of transplantation, cause of ESKD, and pretransplant dialysis duration), acute rejection was independently associated with an increased risk of infectious death (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.20 to 2.30; P=0.002). There was a significant interaction between the era of transplantation and acute rejection with regard to the risk of infectious death (P=0.02). Acute rejection lost statistical significance during the most recent era (P=0.36), whereas among patients transplanted in 1990–1999, acute rejection was associated with increased risk of infectious death (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.35 to 2.74; P<0.001).

Induction with antithymocyte globulin was given to 1.6% of patients transplanted in 1990–1999 and 2.6% of patients transplanted in 2000–2012, and induction with basiliximab was given to 7.3% of patients transplanted in 2000–2012 (basiliximab was not available in the 1990s). Induction was not associated with increased infectious mortality risk after transplantation (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.41 to 1.57; P=0.52, adjusted for age and sex).

Discussion

Our study shows that patient survival after kidney transplantation in Finland has improved and that the risk of death from all causes has decreased. Additionally, the risk of death due to infectious causes is lower in the recent cohort compared with the historic cohort. This is in line with a recent European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association Registry report showing that the risks of cardiovascular and infectious death have fallen by 29% and 8% between 1998–2002 and 2003–2007 (12). All-cause and infection-related mortality have decreased in spite of transplanting older recipients with increasing degree of comorbidity, longer pretransplant dialysis duration, more powerful immunosuppressive therapy, and also, the increased use of marginal donors. The incidence of acute rejection has decreased between the two eras in our cohort, and acute rejection was an independent risk factor for infectious death only in patients transplanted in the 1990s, suggesting that lower frequency of acute rejection and especially, the treatment of acute rejection are the most important factors explaining the reduced infectious mortality in our cohort. In addition, better and faster diagnostic tools for infections together with increased awareness of severe opportunistic infections may have contributed to the reduced infectious mortality.

The particular causes of death among kidney transplant recipients have changed over time. Infections were the most common cause of death in the early years of transplantation (42% in 1980–1989; decreased to 28% in 1990–1999) (3). According to the US Renal Data System Annual Data Report 2012, 33% of the known death causes among patients with transplants were cardiovascular, whereas infections accounted for 18% of deaths (4). Notably, the cause of death was missing or unknown for 68% of these patients with transplants. The United Kingdom Renal Registry has shown a marked decrease in the proportion of cardiovascular deaths among all patients on RRT (from 34% in 2000 to 22% in 2011), but a similar trend was not observed for infection-related mortality, which has remained stable at approximately 18% of all mortality. Among patients with transplants, infection was responsible for 23% of the deaths, and cardiovascular disease was responsible for 18% of the deaths (5). Compared with the general population, kidney transplant recipients have a 32-fold risk of dying of infection, and the risk is particularly emphasized in young women (13). In kidney transplant recipients, the mortality secondary to septicemia is 20-fold compared with the general population, and the mortality secondary to pulmonary infection is twofold compared with the general population (14,15).

Although the incidence of fatal infections after kidney transplantation has decreased over time, studies assessing infectious mortality are scarce, and current information on specific infectious causes of death after kidney transplantation has not been available. In our analysis, common bacterial infections remain the most frequent cause of infection-related mortality, whereas viral, fungal, or unconventional bacterial infections rarely caused deaths after kidney transplantation. It is well known that the spectrum of infections after transplantation varies over time. Early infections during the first month after transplantation are likely to be nosocomial bacterial infections. Opportunistic pathogens occur during the following 5 months as a result of the high level of immunosuppression, and later infections are either opportunistic infections or conventional ones (16,17). According to the US Renal Data System 2003 annual report, 70% of all kidney transplant recipients will experience an infection episode by 3 years after transplantation, and hospitalization for bacterial infections after kidney transplantation is roughly twice as common as hospitalization for viral infections, despite much greater attention to post-transplant viral infections in the published literature (18); infections may be a more common reason for hospitalization after transplantation than acute rejections (19). According to a recent registry analysis among the deceased kidney transplant recipients, in whom the causative infectious agent was known, 85% died of bacterial infections, whereas only 9% died of viral infections, and 6% died of other types of infections (13).

Interestingly, most fatal infections occurred late after transplantation. Mortality rate of infection within 1 year from transplantation was not higher compared with later follow-up. Of the 3249 patients with transplants in this study, only 2.6% died within the first year after transplantation. Infections accounted for 28% of all deaths during the first year, whereas cardiovascular disease was the most common cause of death. This is in contrast with previous studies reporting that, within the first year after transplantation, infections are the leading cause of death (20,21). The risk of death from infections has declined, which may have contributed to the improvement in the 1-year survival rate after kidney transplantation. As the survival of patients with transplants improves, long-term complications of immunosuppression, such as malignancies, raise increased concern, and cancer-related deaths may replace infections as causes of death. In our study, however, both all-cause and cancer-related mortality rates were smaller in the more recent cohort compared with the older cohort.

The low incidence of viral- and fungal-related deaths, even in the first year after transplantation, was somewhat surprising. Only one patient died because of CMV infection. CMV is the most common viral infection after kidney transplantation, affecting 10%–19% of recipients receiving conventional immunosuppressive therapy, but serious disease caused by CMV is rare (6). Antiviral prophylaxis in the highest risk (D+/R−) population has reduced the incidence of CMV disease by 60%, which has contributed to the reduced all-cause mortality (22). Data about donor or recipient serostatus were unfortunately not available for the study. Similarly, only one patient died due to P. jirovecii, arguing either for successful use of prophylaxis in our cohort or that the incidence of P. jirovecii is very low, calling into question the wisdom of extensive prophylaxis with trimethoprim, which is also associated with toxicity and concerns about antimicrobial resistance.

Specific data on infection prophylaxis were not available for the purpose of this study. However, according to the policy in our country, only prophylaxis against P. jirovecii for the first 6 months after transplantation with either trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or pentamidine inhalations was given. Other infection prophylaxis was not routinely used, with the exception of 6-month valganciclovir prophylaxis for CMV-seronegative recipients of a kidney from a seropositive donor initiated in 2004. Our study cohort may also otherwise differ from other kidney transplant cohorts, especially with regard to the almost exclusively white population in Finland, the high frequency of cyclosporin use, and the low frequency of induction therapy, and therefore, our findings may not be directly applicable to other cohorts.

Our study has a few limitations. Death certificates may have limitations in their quality. The Finnish Registry for Kidney Diseases allows only one cause of death to be reported, and some patients may have had several factors leading to death. However, kidney transplant recipients are under continuous medical follow-up, and the causes of death were reported by the treating nephrologist and are the best available data. Earlier Finnish studies have verified the validity and good quality of Finnish death certificates, death certification practices, and the cause of death validation procedures producing the register data on mortality, justifying their use for end point assessment in epidemiologic studies (23–25). In addition, no standardized definition of infectious death exists in the registry or the death certificates (e.g., with regard to the microbiologic or radiologic diagnosis of the infection or timing of death in relation to the infectious diagnosis), and it is only on the basis of the evaluation of the treating physician, which limits the accuracy of our data. Another limitation is that this study focused only on infectious causes of death, and no data were available about nonfatal infections, which also cause substantial morbidity after kidney transplantation. In addition, although some speculation about the reduced risk of infectious deaths can be made with regard to lower incidence of acute rejections in the most recent cohort, our study is limited by the inability to determine with confidence the mechanisms behind the reduced infectious mortality seen between the eras.

In accordance with earlier studies among immunocompromised patients, pulmonary infections remain a major cause of death (26). Pulmonary infection was responsible for most (45%) deaths from infection, and in 55% of these patients, the cause of death was unspecified pneumonia (J18.9). Septicemia accounted for over one third of infectious deaths, and information on the sites of infection or the defined pathogen associated with septicemia was not available in 40% of these patients. This is in accordance with the fact that a pathogen can be identified by blood culture in ≤30%–40% of patients with sepsis (27). In addition to microbiologic criteria, clinical criteria have provided the basis for epidemiologic studies of sepsis since the 1990s (28,29), and clinical sepsis codes have been included in ICD-10 since 2005. In addition, conversion from the older ICD-9 codes to ICD-10 codes may explain some inaccuracy in the diagnoses.

However, the key strength of this study is the virtually complete coverage of kidney transplantations in Finland with complete follow-up data of a large representative national cohort, allowing us to compare mortality in different eras of transplantation. Data about the cause of death were available for all patients included in this study—no deaths were coded as unknown or missing, which minimizes selection bias.

In conclusion, the survival after kidney transplantation in Finland continues to improve. The risk of death due to infections after kidney transplantation has dropped by one half since the 1990s. Common bacterial infections remain the most frequent cause of infection-related mortality, whereas opportunistic viral, fungal, and unconventional bacterial infections rarely cause deaths after kidney transplantation.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Helsinki University Hospital research funds grant TYH2015108 (to I.H.) and the Roche Research Foundation (I.H.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11511017/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wolfe RA, Roys EC, Merion RM: Trends in organ donation and transplantation in the United States, 1999-2008. Am J Transplant 10: 961–972, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hariharan S, Johnson CP, Bresnahan BA, Taranto SE, McIntosh MJ, Stablein D: Improved graft survival after renal transplantation in the United States, 1988 to 1996. N Engl J Med 342: 605–612, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard RJ, Patton PR, Reed AI, Hemming AW, Van der Werf WJ, Pfaff WW, Srinivas TR, Scornik JC: The changing causes of graft loss and death after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 73: 1923–1928, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. U.S. Renal Data System: USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Bethesda, MD, 2008.

- 5.Pruthi R, Steenkamp R, Feest T: UK Renal Registry 16th annual report: Chapter 8 survival and cause of death of UK adult patients on renal replacement therapy in 2012: National and centre-specific analyses. Nephron Clin Pract 125: 139–169, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helanterä I, Schachtner T, Hinrichs C, Salmela K, Kyllönen L, Koskinen P, Lautenschlager I, Reinke P: Current characteristics and outcome of cytomegalovirus infections after kidney transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 16: 568–577, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaub S, Hirsch HH, Dickenmann M, Steiger J, Mihatsch MJ, Hopfer H, Mayr M: Reducing immunosuppression preserves allograft function in presumptive and definitive polyomavirus-associated nephropathy. Am J Transplant 10: 2615–2623, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helanterä I, Anttila VJ, Lappalainen M, Lempinen M, Isoniemi H: Outbreak of influenza A(H1N1) in a kidney transplant unit-protective effect of vaccination. Am J Transplant 15: 2470–2474, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briggs JD: Causes of death after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 1545–1549, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noordzij M, Leffondré K, van Stralen KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Jager KJ: When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2670–2677, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pippias M, Jager KJ, Kramer A, Leivestad T, Sánchez MB, Caskey FJ, Collart F, Couchoud C, Dekker FW, Finne P, Fouque D, Heaf JG, Hemmelder MH, Kramar R, De Meester J, Noordzij M, Palsson R, Pascual J, Zurriaga O, Wanner C, Stel VS: The changing trends and outcomes in renal replacement therapy: Data from the ERA-EDTA Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 831–841, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogelzang JL, van Stralen KJ, Noordzij M, Diez JA, Carrero JJ, Couchoud C, Dekker FW, Finne P, Fouque D, Heaf JG, Hoitsma A, Leivestad T, de Meester J, Metcalfe W, Palsson R, Postorino M, Ravani P, Vanholder R, Wallner M, Wanner C, Groothoff JW, Jager KJ: Mortality from infections and malignancies in patients treated with renal replacement therapy: Data from the ERA-EDTA registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 1028–1037, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL: Mortality caused by sepsis in patients with end-stage renal disease compared with the general population. Kidney Int 58: 1758–1764, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL: Pulmonary infectious mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. Chest 120: 1883–1887, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishman JA: Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 357: 2601–2614, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fishman JA: Infection in organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 17: 856–879, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dharnidharka VR, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC: Risk factors for hospitalization for bacterial or viral infection in renal transplant recipients--an analysis of USRDS data. Am J Transplant 7: 653–661, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dharnidharka VR, Stablein DM, Harmon WE: Post-transplant infections now exceed acute rejection as cause for hospitalization: A report of the NAPRTCS. Am J Transplant 4: 384–389, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arend SM, Mallat MJ, Westendorp RJ, van der Woude FJ, van Es LA: Patient survival after renal transplantation; more than 25 years follow-up. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 1672–1679, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrugia D, Cheshire J, Begaj I, Khosla S, Ray D, Sharif A: Death within the first year after kidney transplantation--an observational cohort study. Transpl Int 27: 262–270, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodson EM, Ladhani M, Webster AC, Strippoli GF, Craig JC: Antiviral medications for preventing cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD003774, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lahti RA, Penttilä A: The validity of death certificates: Routine validation of death certification and its effects on mortality statistics. Forensic Sci Int 115: 15–32, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leppälä JM, Virtamo J, Heinonen OP: Validation of stroke diagnosis in the national hospital discharge register and the register of causes of death in finland. Eur J Epidemiol 15: 155–160, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolonen H, Salomaa V, Torppa J, Sivenius J, Immonen-Räihä P, Lehtonen A; FINSTROKE register : FINSTROKE register. The validation of the finnish hospital discharge register and causes of death register data on stroke diagnoses. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 14: 380–385, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shorr AF, Susla GM, O’Grady NP: Pulmonary infiltrates in the non-HIV-infected immunocompromised patient: Etiologies, diagnostic strategies, and outcomes. Chest 125: 260–271, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angus DC, van der Poll T: Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 369: 840–851, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engel C, Brunkhorst FM, Bone HG, Brunkhorst R, Gerlach H, Grond S, Gruendling M, Huhle G, Jaschinski U, John S, Mayer K, Oppert M, Olthoff D, Quintel M, Ragaller M, Rossaint R, Stuber F, Weiler N, Welte T, Bogatsch H, Hartog C, Loeffler M, Reinhart K: Epidemiology of sepsis in Germany: Results from a national prospective multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 33: 606–618, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleischmann C, Thomas-Rueddel DO, Hartmann M, Hartog CS, Welte T, Heublein S, Dennler U, Reinhart K: Hospital incidence and mortality rates of sepsis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 113: 159–166, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.