Tight, non-active site binding cyclic peptides are promising affinity reagents for studying proteins and their interactions.

Tight, non-active site binding cyclic peptides are promising affinity reagents for studying proteins and their interactions.

Abstract

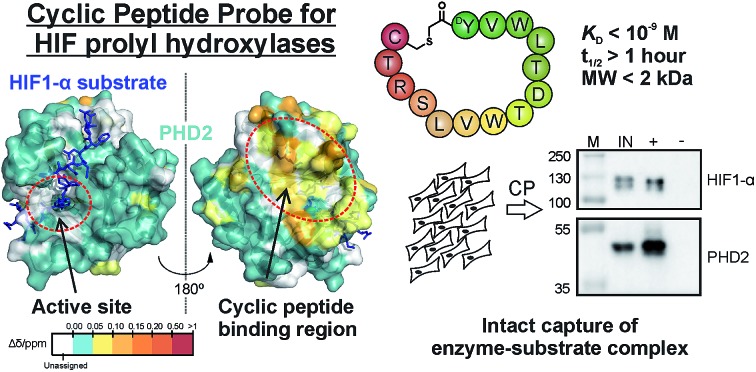

Affinity reagents are of central importance for selectively identifying proteins and investigating their interactions. We report on the development and use of cyclic peptides, identified by mRNA display-based RaPID methodology, that are selective for, and tight binders of, the human hypoxia inducible factor prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) – enzymes crucial in hypoxia sensing. Biophysical analyses reveal the cyclic peptides to bind in a distinct site, away from the enzyme active site pocket, enabling conservation of substrate binding and catalysis. A biotinylated cyclic peptide captures not only the PHDs, but also their primary substrate hypoxia inducible factor HIF1-α. Our work highlights the potential for tight, non-active site binding cyclic peptides to act as promising affinity reagents for studying protein–protein interactions.

Introduction

In investigating the distribution and roles of proteins, researchers often use antibodies, both for identifying proteins and in defining their interactions. Although antibodies are powerful reagents, they can have limitations, including their large size, often poorly-characterised binding modes/affinities, reproducibility issues arising from batch variations, high costs and the use of animals (where immunisation methods are used). Collectively these issues mean antibody-based results are often qualitative and can sometimes give misleading results in protein–protein interaction (PPI) studies,1e.g. when the antibody blocks a relevant binding interaction. Significant efforts have thus been made to develop improved antibodies (e.g. antibody fragments from phage-display,2,3 and nanobodies4) or to develop protein/chemical alternatives (non-immunoglobulin protein5 and peptide6,7 scaffolds, nucleic acid e.g. aptamers,8,9 and inhibitor-based chemical approaches10) to address the demand for reliable protein-binding reagents, both for research and clinical applications. The non-antibody affinity reagents offer improved reproducibility (e.g. when produced in vitro or by chemical synthesis), high affinity, and precise targeting. In practice, however, they have not replaced conventional antibodies, which are finding new applications, e.g. in proteomics.

Genetically encoded peptide screening technologies have emerged as methods that can efficiently generate protein binders with high affinity and selectivity.11–14 The mRNA display based cyclic peptide (CP) generation and screening platform – Random nonstandard Peptide Integrated Discovery (RaPID) - has been applied to enzymes in various pathways and transcriptional regulation (e.g. membrane transporters,15 receptors,16 ubiquitin ligases,17 kinases,18 deacetylases,19 histone demethylases20). Inspired by these results, we were interested to investigate whether CPs generated from ‘RaPID’ selection can be developed as affinity probes. Our enzyme target was the prolyl hydroxylase isoform 2 (PHD2), a hypoxia sensor, which plays a central role in the human hypoxic response. PHDs catalyse hydroxylation of key proline residues of hypoxia inducible factor HIF1-α in an oxygen-dependent manner, which signals for its degradation via the proteasomes21,22 (ESI Fig. 1†). PHD inhibitors are in clinical trials for treatment of anaemia in chronic kidney disease (CKD), because erythropoietin (EPO) is upregulated by HIF.23 While HIF-α is the primary target of the PHDs, they have been reported to associate with and/or and regulate other proteins. To date, validation of these PHD substrates/complexes has been somewhat limited, in part, due to reproducibility issues with antibodies. There is thus a demand for chemical tools targeting PHDs to identify and validate such complexes. Our results reveal the efficiency of the RaPID system for generating non-inhibitory, tight binding CPs that bind away from the active site and that CPs can be used for substrate–enzyme capture studies. Overall, the results demonstrate that the RaPID system enables identification of CPs that complement antibodies for use in protein research.

Results

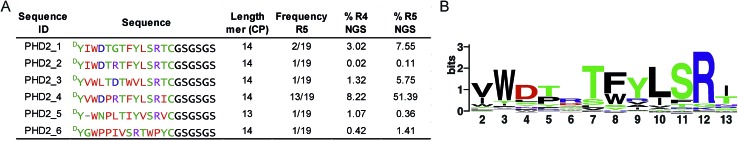

Identification of cyclic peptide binders of PHD2

We set out to investigate the potential of the RaPID system24 for generating tight-binding CPs for human PHDs, using the catalytic domain of PHD2 (residues 181–426, tPHD2) with N-terminal His-tag and C-terminal biotinylation (tPHD2HisBio) (ESI Fig. 2†). An mRNA library,18 which encodes N-chloroacetyl-DTyr (ClAc-DTyr) as a reprogrammed initiator followed by 4–12 mer randomised peptide sequences, a C-terminal cysteine, a linker and a stop codon, was constructed as described.18In vitro translation of the puromycin-fused mRNA library gave an mRNA-displayed CP library via spontaneous posttranslational formation of a thioether linkage between the N-terminal ClAc-DTyr and the C-terminal Cys. The library was applied to biotin-streptavidin beads to eliminate non-specific binding sequences, and subsequently applied to tPHD2HisBio-immobilised streptavidin beads. Recovery of target binding species was monitored by qPCR of the complementary DNA (cDNA), produced from a reverse transcription of the mRNA recovered from the positive and the final negative selection steps in each round; the fraction of recovery was calculated relative to the input library for the selection round. A significant increase in recovery (>5%) was observed after the fifth round (R5) (ESI Fig. 2†). The cDNA from R5 was cloned into pGEMT-Easy vector and transformed into E. coli. Sequencing of 19 colonies resulted in six unique peptide sequences (PHD2_1–PHD2_6), with PHD2_4 appearing with the highest frequency (13/19) (Fig. 1A). Next generation sequencing (NGS) was used to analyse the population distribution of the CP encoding sequences of the fourth (R4) and fifth (R5) selection rounds (Fig. 1). The results were in accord with the colony selection results, but revealed a higher diversity of sequences (these sequences were typically in low abundance, (<0.1% of the total reads)). The most abundant R5 14 mer sequences were used to generate a Logo plot (Fig. 1B, ESI Table 1†),25 revealing a common motif with a Trp towards the N-terminus and a highly conserved “TFYLSR” motif (where X represents any amino acid) at the C-terminus.

Fig. 1. Cyclic peptides identified using the RaPID screening platform against tPHD2. (A) Sequences of cyclic peptides obtained. The sequences identified from the colony sequencing (R5) and corresponding next generation sequencing (NGS) data analysis for cDNA pools from R4 and R5 are indicated as % of the total reads. (B) Logo plot analyses of NGS sequencing data for R5 for 14 mer sequences present at a level of ≥0.01% (256 different peptides). The ‘first’ ring residue is DTyr and the ‘last’ ring residue is Cys for all sequences.

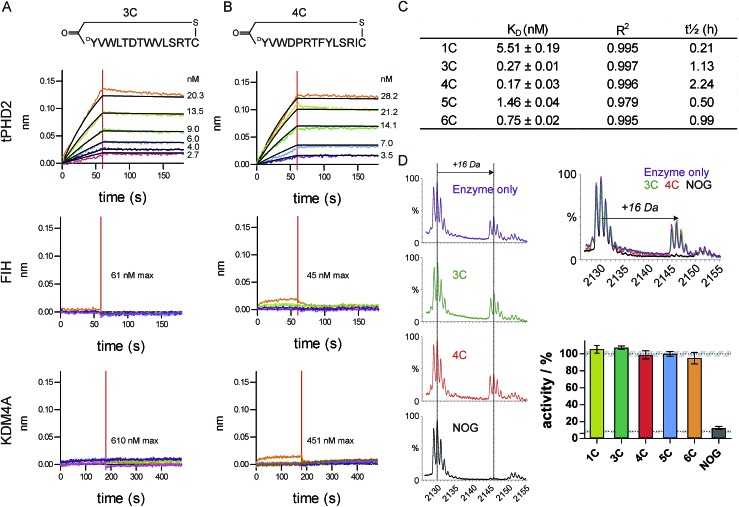

Characterisation of cyclic peptide hits against PHD2

The top five abundant CP sequences were prepared by solid phase peptide synthesis without the (GlySer)3 linker (ESI Table 2†), and their affinities for tPHD2HisBio investigated using biolayer interferometry (BLI) with C-terminal biotin immobilisation (Fig. 2, ESI Fig. 3†). All five CPs bound to tPHD2HisBio with nanomolar to sub-nanomolar KD values, while the PHD2 cognate substrate C-terminal oxygen dependent domain (CODD), a fragment peptide of HIF1-α, bound with KD = 5.2 ± 0.5 μM under the same conditions (similar to the reported surface plasmon resonance value,26Fig. 3D). In particular, 3C and 4C (derived from PHD2_3 and PHD2_4 respectively) were the highest affinity binders, with KD values of 270 pM and 170 pM, and dissociative half-lives t1/2 of 68 min and 134 min, respectively. Similar KD values were obtained using N-terminal His-tag immobilisation (ESI Fig. 4†). The CPs were then tested for binding to representative other human 2OG oxygenases: FIH, a related HIF hydroxylating 2OG oxygenase and KDM4A, a histone demethylase (Fig. 2 and ESI Fig. 5†). CPs showed very weak binding (if any), with 3C showing almost no detectable binding. Since PHD2 catalyses the hydroxylation of Pro residues of HIF, the CP sequences containing Pro (4C, 5C, 6C) were tested as PHD2 substrates; however no enzymatic oxidation was observed (ESI Fig. 6†). All five CPs were tested as inhibitors of CODD hydroxylation but none showed significant effects at >1000 fold excess of the KD (Fig. 2D), implying the peptides do not bind at the active site.

Fig. 2. Characterisation of CP hits. Biolayer interferometry traces for association and dissociation phases of binding for 3C (A) and 4C (B) to tPHD2 (top) and other representative 2OG-oxygenases (FIH (middle) and KDM4A (bottom)), with raw (coloured) and fitted (black) curves shown. (C) BLI KD values for CP binding to tPHD2, as determined by global fitting of the data with ± representing the standard error. Full traces for all peptides are in ESI Fig. 3.† (D) MALDI-TOF MS based PHD2 inhibition assays with representative spectra (LHS) showing CODD hydroxylation (+16 Da peak). (RHS) Bar chart showing the normalised activity of tPHD2 (1 μM) relative to a DMSO control (average ± stdev n = 3). CPs were used at >4-fold excess of enzyme concentration. N-Oxalylglycine (NOG), a 2OG mimicking inhibitor of PHD2, is a positive inhibitor control (10 μM).

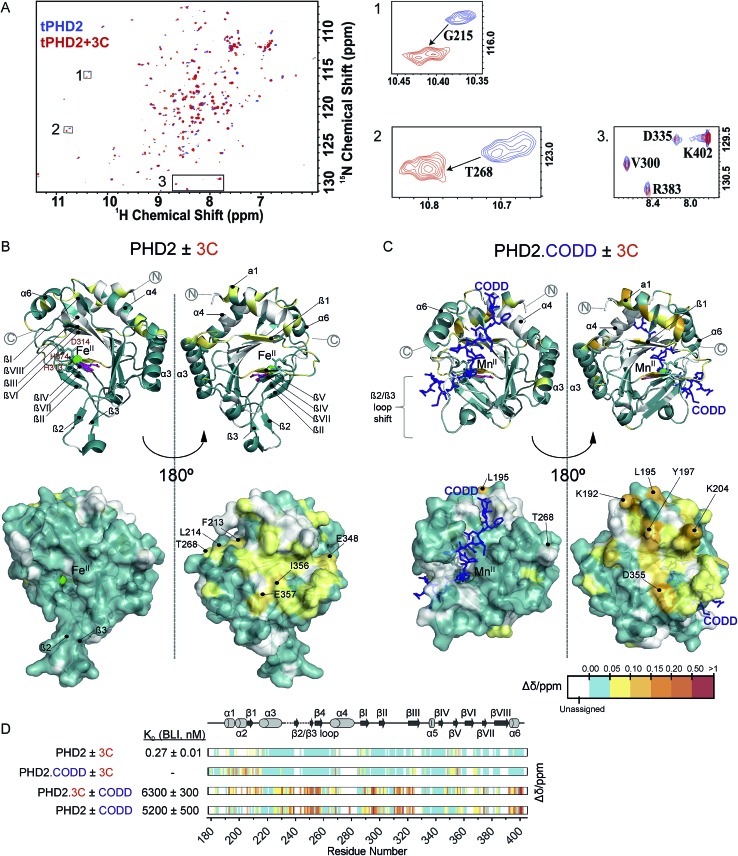

Fig. 3. NMR reveals binding of CPs to PHD2. (A) 1H–15N HSQC of tPHD2 in the presence (red) and absence (blue) of 3C. 1H and 15N chemical shift changes were combined to give a Δδ value, and assignments were made using nearest neighbour assignment method. (B and C) Ribbons (above) and surface (below) representations of chemical shift changes mapped on the “open” form of PHD2 (B), and the “closed” form complexed with CODD (C) crystal structures, shown in two orientations. The substrate binding cleft and the active site are on the opposite face of the protein where most of the residues with changes in chemical shift cluster on 3C binding. Structures used: (B) PDB (; 2G19) PHD2·Fe(ii)·N-[(4-hydroxy8-iodoisoquinoline-3-yl)carbonyl]glycine, (C) PDB : ; 3HQR, PHD2·Mn(ii)·NOG·CODD. Colours: metal (green), small molecule inhibitors (magenta), CODD (blue). (D) Weighted change in chemical shifts for different combinations of PHD2, CODD and 3C overlaid on the secondary structure of tPHD2 (; 2G19) (see ESI† methods for details). KD values were determined using BLI (ESI Fig. 3 and 8†). Shift changes coloured according to their Δδ (heat map); Δδ < 0.05 ppm (cyan) was considered to be insignificant; no colour indicates unassigned/unassignable residues.

Cyclic peptides do not affect HIF peptide binding to PHD2

To investigate the binding regions of the CPs to tPHD2, NMR assays were conducted. Titrations of the highest affinity CPs (3C & 4C) into labelled tPHD2 (181–402, non-tagged) with monitoring by 1H–15N HSQC showed modest changes in the backbone amide chemical shifts of some residues indicating that the peptide is interacting with the protein without disrupting its overall fold (Fig. 3A and B). Comparison of the assigned apo-tPHD2 NMR spectrum27 of tPHD2 with CPs using nearest neighbour assignment showed that both CPs interact with tPHD2 in the same regions (Fig. 3, ESI Fig. 7E†). While the double-stranded β-helix (DSBH, β strands I to VIII) core fold, which supports the active site, is largely unaffected by CP addition, the residues in and around β1/α3 (residues 206–215), α4 (residues 268–270) and βV region of the DSBH (345–360) exhibited substantial changes in the weighted chemical shift on CP binding (Fig. 3B). When mapped onto an existing tPHD2 crystal structure (PDB ; 2G19) the weighted chemical shift changes imply that the affected residues all lie on the same face of the protein, in a relatively ‘flat’ surface, opposite to the active site pocket and the CODD substrate binding region (Fig. 3B).

Using 1H–15N HSQC NMR, we have previously shown that in the presence of saturating HIF-1α CODD, significant shifts in the β2/β3 loop region of tPHD2 (Δδ > 1, ESI Fig. 7E†) are observed, revealing large conformational changes in this region on substrate binding.27 CP binding prior to the addition of CODD did not significantly alter the 1H–15N HSQC of tPHD2:CODD (ESI Fig. 7E†). The weighted chemical shifts mapped onto a crystal structure of the PHD2·CODD complex (PDB ; 3HQR) show the largest shifts to cluster on the opposite face of the protein to the substrate in the same manner as in apo-PHD2 binding (Fig. 3C), further supporting binding of CPs, away from the active site, including in the presence of CODD substrate.

Consistent with this proposal, the binding affinity of CODD for tPHD2, as determined by BLI, was comparable in the absence (KD = 5.2 ± 0.5 μM) and presence (KD = 6.3 ± 0.3 μM) of 3C (Fig. 3D and ESI Fig. 8†), indicating that 3C does not significantly affect the PHD2:CODD interaction. The non-active site nature of the binding was further supported by non-denaturing mass spectrometric analysis of tPHD2, indicating the CPs do not compete with Fe(ii), FG2216 (a clinically trialled 2OG competitive PHD2 inhibitor)28 or substrate (CODD) (ESI Fig. 9†). 3C binding to tPHD2 was abolished under denaturing conditions (ESI Fig. 4†), indicating that the three-dimensional structural fold of tPHD2 is important in CP recognition. Size-exclusion chromatography multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) showed monomeric tPHD2 to bind to 3C (ESI Fig. 10†).

Identification of key interactions of 3C/4C binding.

We next explored the molecular basis for the slow-dissociation kinetics of 3C. A linearised variant of 3C showed very little binding response towards tPHD2HisBio at 3 μM, indicating that the cyclic conformation is important for tight binding affinity (ESI Fig. 3†). We hypothesised that Arg12 of the CPs may be important, not only from its absolute conservation in the selected CPs (Fig. 1B), but also because Arg can form multiple hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions enabling fold stabilisation. Substitution of the Arg12 to Ala in 3C reduced target affinity by over 1000-fold (KD = 783 nM) with a significant decrease in t1/2 from hours to seconds (ESI Fig. 3†), confirming that Arg12 is crucial for potent binding of the CPs to PHD2. Slow dissociation is often associated with conformational change of protein induced by ligand-binding.29 The dramatic shift in the t1/2 may be indicative of changes in the conformation of tPHD2 that ‘lock’ the CP–enzyme complex (consistent with the NMR 1H–15N HSQC results).

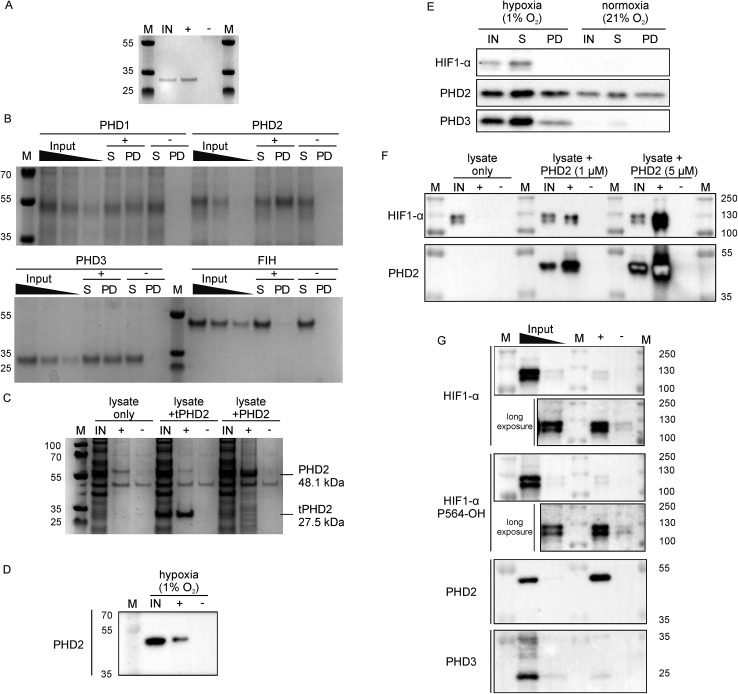

Development of affinity capture probe for PHDs

Since 3C had a very high affinity (KD < nM) with slow dissociation kinetics for PHD2 whilst not disrupting substrate binding, we explored its potential as an affinity-based probe for substrate capture. We synthesised a derivative of 3C with the (GlySer)3 spacer with an azido norleucine residue at the C-terminus (3CAz), which would allow versatility in subsequent modifications (e.g. biotin, fluorescence conjugation). This was then coupled to a biotin derivative with an ethylene glycol linker and a bicyclononyne moiety in a strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition30 to generate 3CBt (ESI Fig. 11†). To test 3CBt as a capture probe, isolated recombinant tPHD2 was incubated with 3CBt, then precipitated using streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads. High levels of tPHD2 recovery were observed as judged by analysis of the captured proteins by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE, with no recovery of tPHD2 using biotin alone (Fig. 4A). A similar pull-down experiment was carried out with recombinant full-length PHD2 and its related isoforms, PHD1 and PHD3, as well as FIH. PHD2 was recovered in a 3CBt-dependent manner (Fig. 4B) indicating that the 3CBt probe maintained its affinity for the full-length multi-domained PHD2. Interestingly, the probe was also able to capture full length PHD1 and PHD3, but not FIH (consistent with BLI experiments (Fig. 2)), suggesting that the 3C binding region is conserved across the PHDs, but not in FIH. Sequence alignments in the light of the NMR results suggest that changes in the conserved β1/α3 (residues 206–215) region of the PHDs (which differs in FIH) is likely involved in CP binding (ESI Fig. 12†).

Fig. 4. Development of 3CBt as a PHD2 capture probe to isolate endogenous protein complexes. Samples were incubated with 3CBt (+) or with biotin (–) and mixed with streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads. After a series of washing steps, proteins bound to the beads were released by heat denaturation and separated by SDS-PAGE. Quantities used in each experiment are listed in ESI Table 3.† ‘M’: molecular weight protein marker, ‘IN’: 10-fold dilution (relative to the pull down sample) of the input sample(s), ‘S’: supernatant, ‘PD’: pull down. (A)–(C) are Coomassie stained gels, (D)–(G) are western blots. (A) Recombinant tPHD2. (B) Recombinant full-length PHD1, 2, 3 and FIH (with molecular weights of 45.7, 48.1, 29.4 and 42.3 kDa respectively). The input was diluted 16, 32 and 64-fold and the supernatant 16-fold relative to the pull-down samples. (C) U2OS cell lysate spiked with recombinant proteins. (D) Endogenous levels of PHD2 from hypoxic (1% O2) Hep3B cell lysates. (E) Pull down of PHD2 and PHD3 from Hep3B cell lysates under different oxygen concentrations. (F) Dose-dependent capture of HIF1-α from RCC4 cells using added recombinant PHD2. (G) Isolation of endogenous levels of the PHD.HIF1α complex by 3CBt from RCC4 cells grown in hypoxia. For HIF1-α blots, longer exposures excluding the most concentrated input lane are shown. An additional lane of markers was included between the inputs and pull down samples to exclude the possibility of leakage between lanes. The input was diluted 10- and 100-fold relative to the pull down sample.

Next, we tested whether 3CBt can capture PHD2 from cell lysates. When recombinant PHD2 (truncated or full length) was added to U2OS cell lysates, both forms of PHD2 were recovered using 3CBt while no recovery was observed with beads alone (Fig. 4C). We next tested whether 3CBt can purify endogenous PHD2 from cell lysates. PHD2 expression levels vary significantly across different cell types and are typically relatively low in normoxia. However, both PHD2 and PHD3 protein production is induced by hypoxia.31 Hep3b cells, which have a relatively high amount of endogenous PHD2 levels in normoxia compared to other cell lines,31 were grown under hypoxic (1% O2) conditions for 20 to 24 h for endogenous (hypoxia induced) PHD capture. Following lysis and affinity-capture with 3CBt, western blot analysis revealed that endogenous levels of PHD2 could be captured from cell lysates in a 3CBt-dependent manner (Fig. 4D). Further detailed immunoblotting analysis of normoxia and hypoxia-treated samples probed for hypoxia related proteins (HIF1-α, PHD2 and PHD3) showed the expected upregulation of these proteins in hypoxia over normoxia.31 3CBt was able to affinity purify endogenous levels of PHD2 from cells grown under both conditions, and PHD3 under hypoxic conditions (endogenous PHD3 under normoxia is at very low levels in Hep3b) (Fig. 4E). PHD1 is not highly expressed in Hep3B cells and, could not be detected in the input cell lysate (data not shown).21

Unlike active-site probes, 3CBt binds in a region away from the active site, preserving the enzyme:substrate interactions, as demonstrated by CODD binding and activity studies with 3C (Fig. 2D and 3D). Thus, we explored the potential of 3CBt to capture enzyme:substrate/ligand (i.e. PHD:HIF) complexes. VHL-deficient RCC4 cells, wherein HIF1-α is constitutively stabilised and abundant,32 were used to test whether 3CBt can be used to co-purify the PHD2:HIF1-α complex. When recombinant PHD2 was spiked into RCC4 cell lysates and precipitated using 3CBt, cellular HIF1-α co-purified with PHD2, in a PHD2 concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, 3CBt could co-purify HIF1-α and PHDs at endogenous levels, when using RCC4 cells in hypoxia (Fig. 4G). This result demonstrates the utility of 3CBt as an affinity-based probe for native PHD:substrate complex pull-down. Interestingly, the co-purified HIF1-α from RCC4 cells in hypoxia was (at least, partially) hydroxylated at CODD (as shown by western blotting for Pro564-OH specific antibody). This observation implies that PHD2 can both catalyse hydroxylation of HIF1-α during the pull-down process, which was carried out at normal atmospheric oxygen levels, and bind hydroxylated HIF1-α. It is consistent with prior work33,34 and with the activity assays carried out with recombinant PHD2 (Fig. 2D). 3CBt binding thus, not only maintains the catalytic activity of PHD2, but is also useful for co-purifying both substrate and product complexes of PHD2. No significant effects on cell proliferation or PHD2 activity were observed when RCC4 cells were dosed with CPs at different oxygen gradients (0.1%, 5% and 21% O2, ESI Fig. 13†). While this may be, in part, due to cell penetration/stability issues, it suggests that CPs may be useful starting points for probe development to study PHD activity and interactions in cells.

Discussion

The RaPID selection method enables fast and efficient screening (weeks) of highly diverse (>1012) CP sequences and generation of high-affinity binders against protein targets.35 We used the RaPID selection to identify CPs binding to PHD2 with KD values in the low- to sub-nM range, with comparable affinities to antibody–antigen interactions.36 While the CPs were high affinity binders, they were neither inhibitors nor substrates of PHD2 (within limits of detection). Both cyclisation and the highly conserved arginine residue at position 12 were important in maintaining tight-binding characteristics of the CPs. Biophysical analyses revealed that CPs and substrate CODD binding to tPHD2 are not mutually exclusive, with CODD binding and hydroxylation by PHD2 being unaffected by CP binding. The CP (3C/4C) binding sites mapped using 1H–15N NMR support the proposed binding mode; the CPs likely bind on the opposite face to which HIF-α ODD substrates bind at the active site pocket, in a relatively ‘flat’ surface of the protein. PHD2 undergoes dynamic conformational change upon substrate binding, with the movement of the β2/β3 loop from an extended position in the apo- form to a ‘closed’ conformation, whereby the loop occludes the active site and interlocks CODD.27,37 NMR analyses show that 3C tightly binds to PHD2 without substantially disrupting its conformational dynamics or catalytic function. CP binding was selective for all three human PHD isoforms (PHD1-3) compared to that for the other tested human 2OG oxygenases, FIH and KDM4A. The region of PHD2 interacting with CPs is likely to be relatively conserved across the three PHD isoforms, assuming they have similar structures since all three PHDs are able to bind to CP (3C). While 3C, in particular, provides a unique pan-PHD recognition tool, further studies on structure-activity-relationship of peptide sequences may allow for fine-tuning for isoform selectivity, based on the evidence that active site isoform selective CPs can be achieved for other 2OG oxygenases20 and other enzyme families.17–19

Interestingly, many reported CPs discovered through the RaPID selection technique or similar methodologies inhibit their enzyme targets.17,18,20,38 By way of example, with another human 2OG oxygenase, the JmjC-domain containing histone demethylase KDM4A, we identified potent active site targeting inhibitors using the same type of procedure.20 The size and the accessibility/plasticity of the active-site pockets of the target proteins likely influence the outcome of the favoured binding modes of the enriched peptides during the screen. KDM4A, with a more open substrate-binding pocket, however, shows little conformational change upon its substrate histone peptide binding. By contrast with KDM4A and FIH, PHD2 has a relatively narrow substrate-binding pocket, with dynamic conformational changes being observed upon HIF-α ODD binding (by NMR and crystallography),37 possibly limiting CP access to the active site during screening, and favouring non-active site binding CPs. Thus, in order to use the RaPID system for identifying non-active site binders, in some cases, it may be beneficial to block the active site region, by using substrates/inhibitors (which could be active site binding CPs).

To explore application of the high affinity and selectivity of CPs in biological assays, we generated a biotin-linked affinity probe for the PHDs, which was able to capture full-length recombinant PHD1-3, as well as endogenously expressed PHD2 and PHD3 from cell lysates. Importantly, 3CBt was also able to pull down HIF1-α, confirming its ability to isolate enzyme–substrate (or product) complexes. Many active-site binding probes incorporate reactive electrophilic/nucleophilic ‘warheads’ or photoactive groups to covalently link to their target protein for efficient target protein pull-down, including those reported for PHD2.39–41 The high affinity of the 3CBt peptide apparently avoids a requirement for such covalent linkage for efficient pull-down, and the nature of the CP interaction which preserves the enzyme:substrate complex provides significant potential as a tool to study interacting partners for PHDs.

As CPs are readily synthesised by solid phase peptide synthesis, they can constitute a cheaper, more efficient and reproducible alternative to current protein-based affinity reagents. Indeed, during this study, independent batches of 3C were synthesised and confirmed to have the same binding affinities to PHD2, demonstrating the robustness and reproducibility of manufacturing CPs. The CPs targeting PHDs only recognised the folded conformation of PHD2 (ESI Fig. 4†), which is useful for intact protein affinity studies. The conformational recognition also suggests CPs that recognise, and potentially stabilise, specific folds could be produced. Furthermore, due to their relative small size (2 kDa) and synthetic tractability compared to antibodies, CPs offer the potential for engineering to enable labelling or targeting applications.

In addition to CPs use for enzyme:substrate complex capture, our work demonstrates the ability of RaPID selection to generate highly potent, tight binding CPs to a relatively flat protein surface. The results thus imply that exploring RaPID generated CPs as new modalities for targeting protein surfaces lacking distinct binding pockets, as present in many PPI sites, will be productive.12,42 While it is yet unknown if the identified region is the site of a biologically relevant for PPI for the HIF hydroxylases, CPs can be used to probe such questions. CPs can further be used as assay development tools, or as starting points for designing drug-like compounds targeting specific PPI sites. The combined results with RaPID generated CPs suggest they have tremendous general potential in functional studies and for enabling drug discovery involving PPIs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the potential of the RaPID methodology for the generation of highly potent non-modulatory, non-active site binding CP probes as exemplified for the human PHD oxygenase subfamily. The results reveal that the CP probes can be designed to bind with sub-nanomolar affinity and selectivity on protein surfaces. Such binding CPs can have valuable applications, as demonstrated by the development of CPs as affinity probes for enzyme–substrate complex capture. Thus, we propose CPs have substantial potential to be developed as powerful, targeted tools for probing proteins and their interaction partners.

Experimental details

Full experimental procedures are detailed in the ESI;† a summary of key experimental methods is given below.

Materials and methods

Production of recombinant proteins

Recombinant forms of tPHD2, tPHD2HisBio, 15N-tPHD2, PHD3, FIH and KDM4A were produced in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. Full-length PHD1 and PHD2 were produced by baculovirus infection of Sf9 insect cells.

Screening of tPHD2 using RaPID system

Flexizyme RNA, tRNAfMetCAU and ClAc-DTyr-tRNAfMetCAU were prepared as reported.17,43 Translation factors, enzymes and ribosome were prepared and mixed as described44–46 giving a modified in vitro translation system used for reprogramming of translation initiation.17,47 The puromycin-fused (NNK)4–12 mRNA library was prepared by in vitro transcription.18 The in vitro selection of CPs binding to tPHD2HisBio was carried out using RaPID system,18 but with minor modifications as outlined in the ESI.†

Illumina sequencing

To construct an Illumina-compatible sequencing library from the DNA sequences recovered after selection, specific forward (P5) and reverse (P7) primers (ESI Table 4†) were designed containing priming sequences complementary to the constant region of the recovered DNA at the 3′ end of the primer and incorporating adaptor sequences necessary for sequencing at the 5′ end (ESI Fig. 14†). Each amplified PCR product was quantitated using a high sensitivity DNA tape on the Tapestation 2000 (Agilent) prior to pooling and final quantification of the library was performed by quantitative PCR using pre-diluted standards (Kapa Biosystems). Paired-end sequencing was performed using a NextSeq 500 (Illumina) with 80 reads in each direction.

Logo plots

Illumina next generation sequencing data from R5 was used to construct logo plots using WebLogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi)25 for 14 mer sequences present at a level of ≥0.01% (256 different peptides).

Biolayer interferometry

Experiments were performed using an OctetRed 384 (ForteBio). Protein was loaded onto the biosensors, the sensors were then subjected to cycles of association/dissociation with a dilution series of peptides. To correct for drift, each experiment included a DMSO only control, the data from which was subtracted from the other sensors and the data globally fit using the ForteBio Data Analysis software (v9.0.0.4).

Chemical synthesis of selected macrocyclic peptides

CP linear precursors were prepared with an amidated C-terminus by standard Fmoc-solid phase synthesis and the N-terminus chloroacetylated. The peptides were cleaved from the resin with a TFA-based cleavage mixture, cyclised, then purified by HPLC. Peptide concentrations were determined using 1H NMR with an internal standard of 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid.

PHD2 enzyme activity assays

CODDmut was used for activity assays to avoid the formation of non-specific methionine oxidation products, which could also exhibit a +16 Da mass shift. Comparisons showed activity equivalent to the ‘natural’ substrate peptide (data not shown). After a suitable reaction time, samples were quenched with 1% (v/v) aqueous formic acid and analysed by Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass-spectrometry. Relative peak intensities of starting material/product were used to calculate level of enzymatic activity.

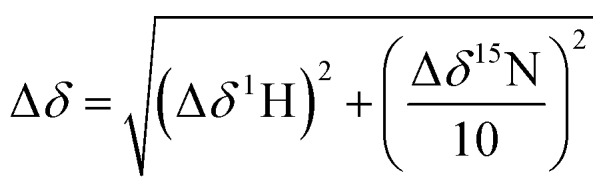

NMR experiments

NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker AVIII 700 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm inverse cryoprobe using 3 mm MATCH NMR tubes (Cortectnet). Weighted amide chemical shift changes (Δδ, in ppm) were determined using eqn (1).48 Protein chemical shift assignments for tPHD2 have been previously reported.27

|

1 |

Capture assays

Cell pellets were lysed using freshly prepared lysis buffer. Lysates were then portioned and recombinant proteins added as required. These solutions were then further divided; one portion added to a solution of 3CBt e.g. 1 mM in DMSO to give a final 3CBt concentration of 10 μM (1% (v/v) DMSO) and the other added to the same volume of biotin (1 mM in DMSO). The solutions were allowed to equilibrate on ice for 1 h before transfer of the entire solution to another tube containing pre-washed, and pelleted Dynabeads® M-280 Streptavidin (Life-technologies, #11205D). The resultant suspensions were incubated at 4 °C for 1 h with gentle mixing before the beads were pelleted using a magnet and washed: once with 1 vol of lysis buffer and twice with 1 vol TBST (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5 at 22 °C), 200 mM NaCl, 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20) with the suspension being transferred to a new tube with the second TBST wash. The beads were resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer, heated to 95 °C for 5 min, and the supernatant recovered. Samples were then separated by SDS-PAGE and either stained with instant blue (Expedeon #ISB1L) or transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride PVDF membrane (Millipore Immobilon-P #IPVH00010). Antibodies were used at 1 : 1000 (v/v) dilution for immunoblotting and were as follows: pan-anti-HIF-1α (clone 54, BD Transduction Laboratories™), anti-HIF-1α Hyp402 (catalogue number 07-1585, Merck Millipore), anti-HIF-1α Hyp564 (D43B5, Cell Signalling), anti-HIF-1α HyN803 (a generous gift from Lee et al.49), HRP-conjugated anti-β-actin (clone AC15, Abcam), and anti-PHD2/PHD3 as reported.31

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence Oxford (RE/08/004/23915), the European Research Council Starting Grant (679479), the British Heart Foundation, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, JST CREST of Molecular Technologies (JPMJCR12L2) to H. S. and a collaborative grant to A. K., the Wellcome Trust (203141/Z/16/Z), Arthritis Research UK (program grant 20522), the William R Miller Junior Research Fellowship from St Edmund Hall Oxford (to R. J. H), a Junior Research Fellowship from Kellogg College Oxford (to M. I. A.), JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Fellows (P14065, to N. D. L.) and the Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship (to A. K.). We thank Dr Emily Flashman and Prof. Chris Pugh for helpful discussions, Dr Adam Hardy, Grace Roper and Leah Taylor Kearney for samples of FIH, KDM4A and PHD2 proteins, Dr Hanna Tarhonskaya for assistance with non-denaturing protein mass spectrometry, Dr Grazyna Kochan (Immunomodulation Group, Navarrabiomed-Biomedical Research Centre) for expression of full length PHD1-3, and Joanna Bonnici for assistance in peptide synthesis.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c8sc00286j

References

- Bradbury A., Pluckthun A. Nature. 2015;518:27–29. doi: 10.1038/518027a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. M., Iorno N., Sierro F., Christ D. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:3001–3008. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty J., Griffiths A. D., Winter G., Chiswell D. J. Nature. 1990;348:552–554. doi: 10.1038/348552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyldermans S. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013;82:775–797. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-063011-092449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrlec K., Strukelj B., Berlec A. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33:408–418. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam R. U., Juraszek J., Brandenburg B., Buyck C., Schepens W. B. G., Kesteleyn B., Stoops B., Vreeken R. J., Vermond J., Goutier W., Tang C., Vogels R., Friesen R. H. E., Goudsmit J., van Dongen M. J. P., Wilson I. A. Science. 2017;358:496–502. doi: 10.1126/science.aan0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millward S. W., Fiacco S., Austin R. J., Roberts R. W. ACS Chem. Biol. 2007;2:625–634. doi: 10.1021/cb7001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold L., Janjic N., Jarvis T., Schneider D., Walker J. J., Wilcox S. K., Zichi D. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2012;4:a003582. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhin A. V., Tarantul V. Z., Gening L. V. Acta Naturae. 2013;5:34–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems L. I., Overkleeft H. S., van Kasteren S. I. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014;25:1181–1191. doi: 10.1021/bc500208y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson K., Ricardo A., Szostak J. W. Drug Discovery Today. 2014;19:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardote T. A., Ciulli A. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:787–794. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennard K. R., Tavassoli A. Chemistry. 2014;20:10608–10614. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinis C., Rutherford T., Freund S., Winter G. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Hipolito C. J., Maturana A. D., Ito K., Kuroda T., Higuchi T., Katoh T., Kato H. E., Hattori M., Kumazaki K., Tsukazaki T., Ishitani R., Suga H., Nureki O. Nature. 2013;496:247. doi: 10.1038/nature12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Sakai K., Suzuki Y., Ozawa N., Hatta T., Natsume T., Matsumoto K., Suga H. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6373. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi Y., Shoji I., Miyagawa S., Kawakami T., Katoh T., Goto Y., Suga H. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:1562–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y., Morimoto J., Suga H. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:607–613. doi: 10.1021/cb200388k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata K., Goto Y., Nishimasu H., Morimoto J., Ishitani R., Dohmae N., Takeda N., Nagai R., Komuro I., Suga H., Nureki O. Structure. 2014;22:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura A., Münzel M., Kojima T., Yapp C., Bhushan B., Goto Y., Tumber A., Katoh T., King O. N. F., Passioura T., Walport L. J., Hatch S. B., Madden S., Müller S., Brennan P. E., Chowdhury R., Hopkinson R. J., Suga H., Schofield C. J. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14773. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield C. J., Ratcliffe P. J. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;338:617–626. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin, Jr. W. G., Ratcliffe P. J. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. C., Holt-Martyn J. P., Schofield C. J., Ratcliffe P. J. Mol. Aspects Med. 2016;47–48:54–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Passioura T., Suga H. Molecules. 2013;18:3502–3528. doi: 10.3390/molecules18033502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J.-M., Brenner S. E. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flashman E., Bagg E. A. L., Chowdhury R., Mecinović J., Loenarz C., McDonough M. A., Hewitson K. S., Schofield C. J. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:3808–3815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury R., Leung I. K. H., Tian Y.-M., Abboud M. I., Ge W., Domene C., Cantrelle F.-X., Landrieu I., Hardy A. P., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Claridge T. D. W., Schofield C. J. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12673. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt W. M., Wiesener M. S., Scigalla P., Chou J., Schmieder R. E., Gunzler V., Eckardt K. U. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:2151–2156. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland R. A., Pompliano D. L., Meek T. D. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2006;5:730–739. doi: 10.1038/nrd2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dommerholt J., Schmidt S., Temming R., Hendriks L. J., Rutjes F. P., van Hest J. C., Lefeber D. J., Friedl P., van Delft F. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:9422–9425. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelhoff R. J., Tian Y.-M., Raval R. R., Turley H., Harris A. L., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Gleadle J. M. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:38458–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval R. R., Lau K. W., Tran M. G., Sowter H. M., Mandriota S. J., Li J. L., Pugh C. W., Maxwell P. H., Harris A. L., Ratcliffe P. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson K. S., Lienard B. M., McDonough M. A., Clifton I. J., Butler D., Soares A. S., Oldham N. J., McNeill L. A., Schofield C. J. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:3293–3301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abboud M. I., McAllister T. E., Leung I. K. H., Chowdhury R., Jorgensen C., Domene C., Mecinovic J., Lippl K., Hancock R. L., Hopkinson R. J., Kawamura A., Claridge T. D. W., Schofield C. J. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:3130–3133. doi: 10.1039/c8cc00387d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipolito C. J., Suga H. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012;16:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry J. P., Fei Y., Zhu X. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2012;10:250–259. doi: 10.1089/adt.2011.0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury R., McDonough M. A., Mecinovic J., Loenarz C., Flashman E., Hewitson K. S., Domene C., Schofield C. J. Structure. 2009;17:981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlippe Y. V., Hartman M. C., Josephson K., Szostak J. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:10469–10477. doi: 10.1021/ja301017y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotili D., Altun M., Hamed R. B., Loenarz C., Thalhammer A., Hopkinson R. J., Tian Y. M., Ratcliffe P. J., Mai A., Kessler B. M., Schofield C. J. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:1488–1490. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04457a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotili D., Altun M., Kawamura A., Wolf A., Fischer R., Leung I. K., Mackeen M. M., Tian Y. M., Ratcliffe P. J., Mai A., Kessler B. M., Schofield C. J. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush J. T., Walport L. J., McGouran J. F., Leung I. K. H., Berridge G., van Berkel S. S., Basak A., Kessler B. M., Schofield C. J. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:4115–4120. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty P. G., Qian Z., Pei D. Biochem. J. 2017;474:1109–1125. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi Y., Shoji I., Miyagawa S., Kawakami T., Katoh T., Goto Y., Suga H. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:1562–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons Jr. W. M., Brodersen D. E., McCutcheon J. P., May J. L., Carter A. P., Morgan-Warren R. J., Wimberly B. T., Ramakrishnan V. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310:827–843. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y., Inoue A., Tomari Y., Suzuki T., Yokogawa T., Nishikawa K., Ueda T. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:751–755. doi: 10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson K., Hartman M. C., Szostak J. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11727–11735. doi: 10.1021/ja0515809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y., Ohta A., Sako Y., Yamagishi Y., Murakami H., Suga H. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008;3:120–129. doi: 10.1021/cb700233t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J., Fairbrother W. J., Palmer III A. G. and Skelton N. J., Protein NMR Spectroscopy, Burlington Academic Press, 2nd edn, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Jeong Hee M., Eun Ah C., Ryu S. E., Myung Kyu L. J. Biomol. Screening. 2008;13:494–503. doi: 10.1177/1087057108318800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.