Abstract

This longitudinal study examines the effect of sons’ incarceration on their mothers’ psychological distress. Interviews were conducted over the life course with a community cohort of African American mothers who had children in first grade in 1966 – 1967 when the study began (N = 615). Thirty years later, their sons had significant rates of incarceration (22.4%). Structural equation modeling showed that the more recent the incarceration, the greater the mothers’ psychological distress, even controlling for earlier socioeconomic status and psychological well-being. Financial difficulties and greater burden of grandparenting are associated with having a son incarcerated and they mediate the relationship between the incarceration and a mother’s psychological distress. Results suggest that incarceration has important effects on family members’ well-being.

Keywords: African American families, incarceration, mothers, psychological distress

One third of Black men will spend time in a jail or prison in their lifetime, a rate eight times that of Whites, according to the Department of Justice (Bonczar, 2003). In fact, incarceration is more common for African American men than obtaining a college degree or serving in the military (Pettit & Western, 2004). Despite these troubling statistics, little is known about the consequences for the families of those confined by the criminal justice system.

Incarceration is a significant family disruption (Arditti, Lambert-Shute, & Joest, 2003; Hairston, 2001). Travis and Waul (2003) propose that incarceration may elicit mixed emotion in families; the grief and anxiety associated with forced separation and the loss of emotional and monetary support is accompanied by hope for ending a destructive lifestyle. Existing family research on the effect of incarceration on families focuses on effects on prisoners’ children, such as behavioral, emotional, and school problems, and on perinatal and neonatal problems in children born to incarcerated mothers (see Johnston, 1995, for a review). Others report on family financial, social, emotional, and health effects, primarily on the wives of the prisoner (Arditti et al.; Comfort, 2003; Girshick, 1996; Lowenstein, 1984).

This article examines the psychological health effects of incarceration of adult sons on mothers in an African American population and considers potential mechanisms that may explain this relationship. Our research framework builds on previous work by conceptualizing incarceration as a stressful event that may lead to adverse consequences for families. We draw on literature linking stress to adverse psychological health (e.g., Avison & Turner, 1988; Pearlin & Johnson, 1977). Pearlin (1989) describes a jail sentence as a chronic stressor given that a series of stressful events usually leads up to the incarceration. Although incarceration is an event that unfolds across time, the initial effect of having a child incarcerated is expected to have the greatest effect, as over time, an individual may be able to accommodate to the stress associated with incarceration, and thus the initial effect may lessen (DeLongis, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1988).

Effects on African American mothers should be considered for numerous reasons. It is known that adult children’s behavior and problems affect parents’ well-being (Minkler, Roe, & Price, 1992; Nelson, 2002; Pillemer & Suitor, 1991). Studies of African American families show that adult children are typically central to their parents’ support network (Barker, Morrow, & Mitteness, 1998; Taylor & Chatters, 1991), and the loss of a son to incarceration can remove an important source of emotional and financial support (Harlow, 1998). Further, Brodsky (1975) reports that the most secure family relationship for a male prisoner is with his mother.

To contribute to this body of work, we consider the influence of incarceration of adult sons on mothers’ psychological distress by comparing mothers with and without adult sons who have been incarcerated. Our models take into account how recently the incarceration occurs, acknowledging the more recent the incarceration the more distressing it may be to mothers. We examine whether financial difficulties, diminishing social ties, poor parenting appraisals, and burden of caring for grandchildren mediate the relationship between mothers’ psychological health and sons’ incarceration.

Financial difficulties may be one pathway through which incarceration of an adult son affects a mother’s psychological distress because incarceration often results in the removal of an important source of family income (Harlow, 1998) and typically affects the most socioeconomically disadvantaged members of society (Pettit & Western, 2004). Additional financial burden associated with incarceration may be incurred, for example, attorney fees, costs of collect telephone calls, contributions to commissary accounts, travel for visitation, or paying off debts incurred by the son (Arditti et al., 2003). Even after release from prison, financial strain may continue because of poor employment prospects (Holzer, Raphael, & Stoll, 2004). As a multitude of studies shows, financial difficulties increase emotional distress (e.g., Dohrenwend, 1973; Link & Phelan, 1995; Turner & Roszell, 1994) and thus may be an important link.

The mother’s social ties may mediate the effect on the psychological distress of having a son who has been incarcerated. Incarceration of a loved one is a stigmatizing event that can lead to withdrawal from social institutions and supports (Hairston, 2003; Lowenstein, 1986), and lack of social ties can have significant health effects (Cohen & Wills, 1985; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Sarason, Pierce, & Sarason, 1994).

Mothers’ parenting self-appraisal may mediate the influence on their psychological distress of having a son who has been incarcerated. Because mothers may blame themselves for the incarceration, we explore whether feelings of failure for not being able to help their child avoid criminal involvement may then affect their psychological health. Studies have shown that feelings of failure around incarceration can lead to poor psychological health (Hairston, 2003).

Finally, incarceration may result in an increased burden of caring for grandchildren, which can have adverse effects on psychological well-being. The burden of grandparenting may be present whether or not the grandmother is the primary caregiver (Lee, Ensminger, & LaVeist, 2005). When sons, rather than daughters, are incarcerated, it is less likely that grandmothers become the primary caregiver (Mumola, 2000; Ruiz, 2002); however, their caregiving responsibility may still increase. Mumola found that most inmates had minor children and name grandparents as an important caregiver. Increased participation in raising grandchildren as a result of their adult children’s problems may become burdensome and may lead to adverse health effects (Sands & Goldberg-Glen, 2000), as well as to the neglect of their own health needs to provide health care for grandchildren (Poe, 1992). Specifically related to illegal drug involvement by adult children (a common reason for incarceration in inner cities). Burton (1992) reported heightened physical illness, depression, anxiety, and poor health behaviors among grandmother caregivers.

Recognizing that those most likely to have a son incarcerated may also be those most likely to experience psychological distress, we control for a number of early indicators expected to be related to both later psychological health and the likelihood of having a son incarcerated. We include measures of early socioeconomic status (i.e., income, education) as control variables to take into account that financial strain increases the risk for incarceration, can be a result of incarceration (Watts & Nightengale, 1996), and is associated with poor psychological health (e.g., Dohrenwend, 1973). We also include early measures of psychological health because of the stability of health over time (e.g., Lovibond, 1998) and because unhealthy mothers may have an increased risk of having an incarcerated son.

Method

Participants

This analysis uses data from the Woodlawn Study, a prospective study of African Americans in the Woodlawn community of Chicago (Ensminger & Juon, 2001; Kellam, Branch, Agrawal, & Ensminger, 1975). Mothers or mother surrogates of first graders in the community’s 12 public and parochial schools participated in the research and intervention program. Three mother interviews were conducted: in 1966 – 1967 when the focal child was in first grade, in 1975 – 1976 when the child was an adolescent, and in 1997 – 1998 when the focal child was a young adult. Data from Times 1 and 3 were used in this study. When the study began, 1,242 mothers and children were recruited into the study. Less than 1% of families of Woodlawn first graders declined participation (N = 13). In 1997 – 1998, effort was made to contact all mothers; 89% (N = 1,008) were located; 25% were found to be deceased (N = 256), 2% (N = 23) were too incapacitated to participate, and 5% (N = 48) refused. Of those located and alive (N = 752), 680 or 90% were interviewed. Of those interviewed, 625 (92%) provided complete data necessary for the present analysis. Mothers were asked whether anyone in their family had gone to jail or prison and if so who; 138 mothers reported having a son who had been incarcerated, and 10 mothers reported that a daughter had been incarcerated. Because there may be differences in the effect of having a son compared to a daughter incarcerated and because there were few mothers with incarcerated daughters, we dropped these 10 cases from our analyses. Thus, 615 mothers make up the population in the present study.

Comparisons made between those interviewed in 1997 – 1998 and those unavailable show no differences on early key variables such as teenage motherhood, family composition, or initial reports of depressed or anxious mood. Those who refused to be interviewed were more likely to have been below the poverty line and receiving welfare at the start of the study, whereas those who had died were less likely to be high school graduates (Ensminger & Juon, 2001).

Woodlawn is one of 76 community areas in Chicago and is located on the south side of the city. In the 1960s, Woodlawn was characterized by high rates of crime, poverty, unemployment, and overcrowding. In spite of these characteristics, there was variation among the mothers with some being employed and owning their homes. When the study began, the mean age of mothers was 32 years (range 19 – 51). On average, mothers had five children. In 1997 – 1998, when the mothers were reinterviewed, 87% were still living in the Chicago area. See Table 1 for select characteristics of the study population by whether they had an incarcerated son.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Mothers at Third Follow-Up Assessment (1997 – 1998) by Incarceration Status of Sons (N = 615)

| Variable | Mothers Without Incarcerated Sons (N = 477) | Mothers With Incarcerated Sons (N = 138) | Test Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 61.83, 5.589 | 61.72,5.330 | t = .201 |

| Marital status (%) | χ2 = 9.185† | ||

| Married | 33.8 | 21.0 | |

| Cohabiting | 1.5 | 1.4 | |

| Divorced/separated | 29.2 | 37.0 | |

| Widowed | 29.0 | 31.2 | |

| Never married | 6.5 | 9.4 | |

| Household composition (%) | χ2 = 10.173* | ||

| Live alone | 21.3 | 18.1 | |

| Live with husband or partner | 20.8 | 14.5 | |

| Live with adult child(ren) | 36.4 | 50.0 | |

| Live with husband and adult child(ren) | 13.1 | 8.0 | |

| Live with others | 8.4 | 9.4 | |

| Education (%) | χ2 = 16.80** | ||

| Less than high school | 52.0 | 64.5 | |

| High school | 35.0 | 34.1 | |

| More than high school | 13.0 | 1.4 | |

| Employment (%) | χ2 = 2.218 | ||

| Employed | 40.3 | 37.7 | |

| Retired | 40.9 | 37.7 | |

| Other | 18.9 | 24.6 | |

| Annual household income 1996 (%) | χ2 = 6.931† | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 25.6 | 33.3 | |

| $10,000–$25,000 | 31.9 | 23.2 | |

| $25,000 or more | 26.8 | 23.2 | |

| Missing | 15.7 | 20.3 |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Procedure

Mother interviews were conducted by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago using trained African American interviewers. The initial interview not only focused on the mother’s first-grade child but also included questions about her household, living situation, employment, economic situations, social relationships, and health. The 1997 – 1998 interview included standardized questions on topics such as her physical and mental health, substance use, community participation, social support, family relationships, employment, financial issues, and neighborhood characteristics.

Measures

Dependent variable

The dependent variable, psychological distress, was a latent variable with two indicators from the 1997 – 1998 interview and was based on measures used in a 1990 national U.S. telephone survey (Mirowsky & Ross, 1992). Anxious mood was the sum of responses to three questions: “How often in the past 12 months have you (a) worried a lot about little things; (b) felt anxious, tense, or nervous; and (c) felt restless or fidgety?” Responses ranged from never (1) to often (5) (α = .85, M = 6.39). Depressed mood was the sum of responses to 10 items with which respondents reported how often during the past 12 months they felt sad, felt lonely, felt they could not shake the blues, felt depressed, had been bothered by things that do not usually bother them, wondered if anything was worthwhile any more, felt nothing turned out the way they wanted, felt completely hopeless, felt worthless, and thought about taking their own life (1 = never, 5 = often; α = .89, M = 18.05). Anxious mood and depressed mood are highly correlated with one another (r = .71, p<.01).

Independent variable

The main independent variable was reported by the mothers in the 1997 – 1998 interview. Mothers were asked if anyone in their family had gone to jail or prison in the past 20 years. If yes, mothers were asked if it was in the past year, the past 5 years, or longer. Focusing on only sons, we created a variable with four levels based on the recency of the incarceration (0 = never having a son incarcerated [77.6%], 1 = having a son incarcerated > 5 years ago [9.6%], 2 = having a son incarcerated 1 – 5 years ago [7.8%], 3 = having a son incarcerated within the past year [5.0%]).

Mediating variables

Five potential mediators from the mothers’ most recent assessment were considered: financial difficulties, frequency of church attendance, personal social ties, parenting appraisal, and grandparenting burden. All were observed variables. Mother’s financial difficulties was a sum of responses to 10 items about financial problems in the past year (e.g., difficulty paying rent, mortgage, or bills; had anything repossessed; postponed getting medication or medical treatment because of the cost; pawning, trading, or selling items or services for cash) (α = .70, M = 0.96, range = 0 – 10). Church attendance, a measure of structural ties, was based on a single question pertaining to her frequency of church attendance (1 = never, 7 = several times per week; M = 5.11). The personal, social ties measure was a sum of four questions pertaining to the respondent’s frequency of socializing, phone conversations, opportunities to confide, and rating of how well she was doing with friends (α = .54, M = 18.16, range 4 – 23). Mothers’ parenting appraisal was measured by two items: how she is doing as a parent to the Woodlawn focal child presently and how she is doing as a parent to her other children. Ratings were on a 6-point scale of 1 (not so well) to 6 (very well). The mean of these two questions was used (M = 5.66, r = 0.65, p < .01). Mother’s assessment of how burdened she was by grandparenthood was a single item with a 6-point scale (1 = not at all burdened, 6 = very much burdened; M = 1.62).

Control variables

At the initial interview, each mother was asked to report her total household income for 1966 before taxes on a 10-point scale (1 = <$2,000 to 10 = ≥$10,000; M = 4.99) and the number of years of schooling she had completed (M = 10.75, range 0 – 18). Mothers’ early psychological distress construct comprised two indicators collected at the initial assessment: anxious mood (“How often do you have days when you are nervous?”) and depressed mood (“How often do you have days when you are sad and blue?”). Both were measured on a 4-point scale (1 = hardly ever, 4 = very often; M for anxious mood = 1.37, M for depressed mood = 0.84). When compared with multi-item scales of depressed and anxious feelings asked at the 1975 interview, these two global items were strongly and positively correlated (see Brown, Adams, & Kellam, 1981).

Analysis Plan

Structural equation modeling (SEM) with latent variables was the main analysis technique employed. SEM was selected because of the longitudinal nature of the data, the ability of latent variables to correct for measurement error, and our interest in testing the statistical significance of direct and indirect effects. Using covariance matrices, the AMOS 5 statistical package provided maximum likelihood estimates for structural equation models (Arbuckle, 2003). Significance of direct and indirect effects, automatically provided by AMOS, was tested using the bootstrapping method, which presents bias-corrected confidence intervals and corrects for nonnormal distributions (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993). Bootstrap estimates of indirect effects were used to examine whether the effect of son’s incarceration on mother’s psychological distress is mediated by at least one of the five proposed mediators in the model. Our approach for testing multiple mediators and their significance is consistent with that recommended by Shrout and Bolger (2002) and Baron and Kenny (1986).

One SEM model was generated. This model tests the direct and indirect effect of incarceration of an adult son on mother’s psychological distress and direct effects of the mediators on psychological distress. In this model, the control constructs/variables from 1966 to 1967 were correlated with one another and modeled to predict the son’s recency of incarceration, each mediator, and mothers’ psychological distress. Pathways were included from incarceration to all mediators and to psychological distress. The associations among mediators were taken into account by correlating their residuals. The residual correlation between any two mediators is the partial correlation of the two variables, controlling for all variables modeled to predict them. Each mediator predicted psychological distress.

To assess model fit, several commonly used indices were examined, including the traditional chi-square discrepancy test, the relative chi-square index (χ2/df), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), and the normed fit index (NFI) (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Bollen, 1989). A nonsignificant p value on the chi-square discrepancy test is desired and suggests the given model’s covariance structure is not significantly different from the observed covariance matrix. The relative chi-square index is an absolute index designed to tell whether the residual or unexplained variance is appreciable. A value of 5.0 or lower is considered a good fit. GFI is another absolute index with a 0 – 1 interval in which 1 indicates perfect model fit. A fit of 0.9 or higher is considered acceptable fit. AGFI is a goodness-of-fit test that adjusts for the degrees of freedom; a value over 0.8 suggests good fit. NFI, a relative fit index, reflects the proportion by which the model improves fit compared to a null model and also varies from 0 to 1; a value of over 0.9 indicates good fit.

Missing Data

As missing-data techniques in AMOS do not allow for bootstrapping and thus confidence intervals for indirect effects, only the list-wise deletion results are presented. Data at both times of assessment were missing, resulting in a loss of 9% of cases. The majority of missingness was a result of mothers not reporting their income at the initial assessment. Many other studies have also found income data to be missing, indicating that income is among the most sensitive questions to many respondents (Demo & Acock, 1996; Guralnik, Fried, Simonsick, Kasper, & Lafferty, 1995). To ensure our list-wise deletion did not bias results, we also conducted direct maximum likelihood estimation for missing data and found no meaningful differences in statistical significance or estimates.

Results

Table 2 presents a correlation matrix showing the associations between mothers’ psychological distress, having a son who was incarcerated more recently, five potential mediators, and controls for early socioeconomic status and psychological distress. Consistent with our central hypothesis, the recency of sons’ incarceration is associated with mothers’ greater psychological distress at the follow-up assessment (r = .201, p < .01). Consistent with the mediation hypotheses, having a son incarcerated more recently is associated with more financial difficulties (p < .001), less church attendance (p = .051), weaker personal ties (p = .029), worse parenting appraisals (p < .001), and a greater burden of caring for grandchildren (p < .001). Also consistent with our mediation hypotheses, all mediators are associated with mothers’ psychological distress at the follow-up assessment (ps < .01). All control variables are significantly correlated with the outcome of interest: mothers’ psychological distress in 1997 – 1998 (p < .01). Table 2 also provides variances for the study constructs/variables.

Table 2.

Correlations and Variances (N = 615)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological distress T3a | .413 | |||||||||

| 2. Son’s recency of incarceration | .201** | .700 | ||||||||

| 3. Financial problems | .343** | .223** | 2.163 | |||||||

| 4. Church attendance | −.178** | −.079† | −.022 | 2.766 | ||||||

| 5. Personal social ties | −.172** | −.088* | −.107** | .288** | 13.594 | |||||

| 6. Parenting appraisal | −.187** | −.145** | −.120** | .128** | .223* | .547 | ||||

| 7. Grandparent burden | .253** | .149** | .118** | −.029 | −.188** | −.187** | 1.689 | |||

| 8. Family income T1b | −.129** | −.151** | −.144** | .130** | .007 | .018 | −.071 | 7.389 | ||

| 9. Education T1b | −.146** | −.195** | −.090* | .067 | .152** | .038 | −.124** | .283** | 4.891 | |

| 10. Psychological distress T1b | .359** | .131 | .081 | −.141** | −.159* | −.138† | .106 | −.177* | −.180* | 34.188 |

Note: Variances are shown on the diagonal.

1997 – 1998 assessment.

1966 – 1967 assessment.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

SEM Analyses

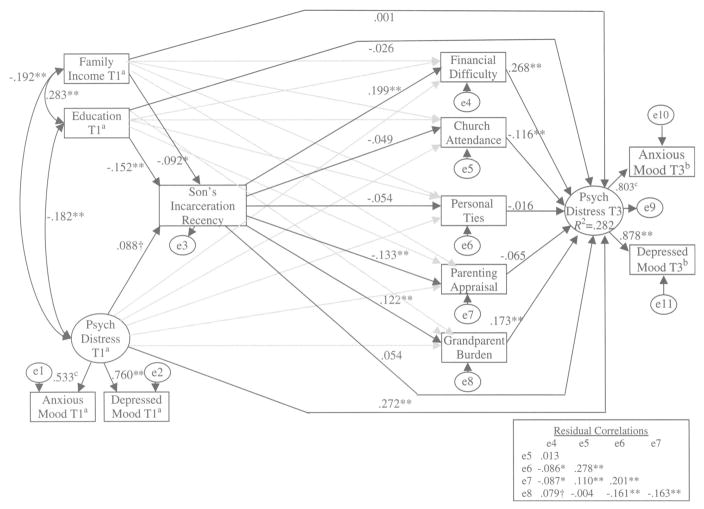

Our model tested the direct and indirect effect of the recency of a son’s incarceration on his mother’s psychological distress controlling for early psychological health and socioeconomic status (see Figure 1). All the factor loadings were statistically significant and substantial ranging from .53 to .88. We found that having a son who has been incarcerated more recently is only indirectly associated with later psychological distress (β = .090, p = .007) as the direct effect is not statistically significant (β = .054, p = .186). This results in a total standardized effect of incarceration on mother’s psychological distress of .144 (p = .004). There is a significant effect of the incarceration variable on financial difficulties and grandparenting burden, which both significantly predict psychological distress, providing evidence of mediation. The variables/constructs in this model predict 28% of the variance in psychological distress at the third assessment. Fit statistics for this model indicate good fit (χ2 = 13.938, df = 17, p = .671, χ2/df = .820, GFI = .996, AGFI = .983, NFI = .987). See Table 3 for path coefficients (direct standardized effects) and Table 4 for variances and R2 values.

Figure 1.

SEM Model of the Standardized Effects of Son’s Incarceration on Mother’s Psychological Well-Being (N = 615)

Note: Path coefficients from control variables to mediators are shown in Table 2. χ2 = 13.938, df = 17, p = .671, χ2/df = .820, GFI = .996, AGFI = .983, NFI = .987.

a1966 – 1967 assessment. b1997 – 1998 assessment. cFixed parameter.

†p <.10. *p < .05. **p< .01.

Table 3.

Unstandardized (b) and Standardized (β) Parameter Estimates, Standard Errors, and Significance Levels for Structural Model: Incarceration Recency, Financial Difficulty, Church Attendance, Personal Ties, Parenting Appraisal, Grandparenting Burden, and Psychological Distress

| b(SE) | β | |

|---|---|---|

| Effects on incarceration recency | ||

| Psychology distress T1a → son’s incarceration recency | 0.111 (.067)† | .088 |

| Income T1a → son’s incarceration recency | −0.028 (.013)* | −.092 |

| Education → son’s incarceration recency | −0.057 (.016)** | −.152 |

| Effects on mediators | ||

| Psychology distress T1a → financial difficulty | 0.086 (.115) | .038 |

| IncomeT1a → financial difficulty | −0.055 (.022)* | −.102 |

| Education → financial difficulty | −0.010 (.028) | −.015 |

| Son’s incarceration recency → financial difficulty | 0.350 (.071)** | .199 |

| Psychology distress T1a → church attendance frequency | −0.227 (.136)† | −.090 |

| Income T1a → church attendance frequency | 0.063 (.026)* | .103 |

| Education → church attendance frequency | 0.009 (.032) | .012 |

| Son’s incarceration recency → church attendance frequency | −0.097 (.082) | −.049 |

| Psychology distress T1a → personal social ties | −0.722 (.309) | −.129 |

| Income T1a → personal social ties | −0.085 (.057) | −.063 |

| Education → personal social ties | 0.224 (.071)** | .134 |

| Son’s incarceration recency → personal social ties | −0.238 (.180) | −.054 |

| Psychology distress T1a → parenting appraisal | −0.137 (.062)* | −.122 |

| Income T1a → parenting appraisal | −0.006 (.012) | −.023 |

| Education → parenting appraisal | −0.002 (.014) | −.005 |

| Son’s incarceration recency → parenting appraisal | −0.118 (.036)** | −.133 |

| Psychology distress T1a → grandparent burden | 0.131 (.104) | .066 |

| Income T1a → grandparent burden | −0.008 (.020) | −.017 |

| Education → grandparent burden | −0.049 (.025)† | −.083 |

| Son’s incarceration recency → grandparent burden | 0.189 (.064)** | .122 |

| Effects on psychological distress | ||

| Psychology distress T1a → psychology distress T3b | 2.399 (.595)** | .272 |

| Income T1a → psychology distress T3b | 0.002 (.091) | .001 |

| Education → psychology distress T3b | −0.068 (.113) | −.026 |

| Son’s incarceration recency → psychology distress T3b | 0.377 (.291) | .054 |

| Financial difficulty → psychology distress T3b | 1.062 (.165)** | .268 |

| Church attendance frequency → psychology distress T3b | −0.407 (.147)** | −.116 |

| Personal social ties → psychology distress T3b | −0.026 (.068) | −.016 |

| Parenting appraisal → psychology distress T3b | −0.511 (.328) | −.065 |

| Grandparent burden → Psychology distress T3b | 0.776 (.185)** | .173 |

1966 – 1967 assessment.

1997 – 1998 assessment.

p <.10.

p <.05.

p <.01.

Table 4.

Model Variances and R2

| Variances | R | |

|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood T1a | 0.318 | .578 |

| Anxious mood T1a | 0.670 | .284 |

| Psychological distress T1a | 0.436 | — |

| Education | 4.883 | — |

| Income | 7.377 | — |

| Son’s incarceration recency | 0.661 | .055 |

| Financial difficulty | 2.022 | .064 |

| Church attendance frequency | 2.682 | .029 |

| Parenting appraisal | 0.527 | .035 |

| Personal social ties | 12.971 | .044 |

| Grandparent burden | 1.625 | .037 |

| Psychological distress T3b | 24.270 | .284 |

| Depressed mood T3b | 10.059 | .771 |

| Anxious mood T3b | 2.771 | .645 |

1966 – 1967 assessment.

1997 – 1998 assessment.

Summary of Findings

Results indicate that having a son who has been incarcerated more recently is associated with mother’s poorer psychological well-being (r = .201, p < .01). Results from our model suggest that this association is an indirect one through the mother’s financial difficulties and greater burden of grandparenting. Mothers’ personal social ties and parenting appraisal are not associated with psychological distress in the model. Neither is there an association between recency of a son’s incarceration and mother’s personal ties or church attendance. Thus, we found no support for personal or structural ties or parenting appraisal as mediators of the association between the recency of a son’s incarceration and mother’s psychological distress.

Conclusion

In this study of African American mothers, we found a small but significant relationship between having a son incarcerated and psychological distress, even after controlling for earlier psychological well-being and SES. The more recent the incarceration, the greater the mother’s distress. This finding is important considering the high and rising rates of incarceration, especially in African American communities. Almost one quarter of women in this community cohort (22.4%) reported having a son who has been incarcerated. Theoretically, our findings continue to highlight the importance of stressful events that occur to family members (Conger, Rueter, & Conger, 2000) and to consider incarceration as a major source of stress to African American families.

This study provides preliminary evidence of the mechanisms through which incarceration of a family member is associated with a mother’s psychological distress. Whereas other studies have suggested possible pathways (e.g., Arditti et al., 2003), this study tests their plausibility. Specifically, as hypothesized, financial difficulties and the burden of caring for grandchildren help explain the relationship between having a son who has been incarcerated and a mother’s psychological well-being. We found that incarceration of a son may be financially burdensome and may lead to increased burden of caring for grandchildren, which are both associated with increased psychological distress.

We did not find evidence that institutional ties, specifically mother’s church attendance, or personal ties mediated the effect of having an incarcerated son on a mother’s psychological well-being. Although we had thought having a son incarcerated may be associated with stigma and shame, causing mothers to withdraw from social institutional resources, such as church, this was not the case. Neither did we find personal social ties to be a mediator. We suspect that mothers’ personal social ties are partly based within families who are also experiencing the incarceration consequences, and thus some of these personal social ties may be burdensome, whereas others may be supportive. This conclusion is consistent with conceptualizations suggested by Sarason et al. (1994) in which the perception of social support is more relevant than the actual presence of ties to mental health functioning. A second explanation of this lack of association may be the result of the poor internal consistency of our measure of personal social ties. Further research should consider this. Although we found an association between incarceration and a mother’s parenting appraisal (i.e., the more recent the incarceration, the poorer the parenting appraisal), the parenting appraisal measure was not associated with mother’s psychological distress. Mothers with a son incarcerated more recently did rate their parenting as poorer, but this poorer appraisal did not contribute to psychological distress once the other mediators were considered.

A major strength of this study is the use of prospective, longitudinal data collected over more than 30 years from a community-based population. This allowed us to control for early factors that may have influenced the outcome. Mothers whose sons became incarcerated were more likely to be poor, to report depressed feelings, and to be less educated before the incarceration occurred. These differences may have contributed to the sons’ problems and enhanced their likelihood of incarceration. The effect of a son’s incarceration on mother’s psychological distress persists, however, even after controlling for these earlier differences. Our findings do suggest that mother’s early psychological well-being and SES have an important association with later life events, such as incarceration of children.

Although our findings suggest important associations, there are limitations. First, it may be that a third unmeasured variable may account for both the son’s incarceration and the mother’s psychological distress. Although we controlled for a number of potentially confounding variables, such as poverty, education, and early psychological status, there may be other confounds that we did not consider or that were unavailable in our data, such as early family structure. Additionally, a son’s incarceration may represent broader family problems, such as substance abuse or family criminality. Although information collected from the mothers showed that mothers themselves had very low rates of lifetime substance use (<3%), it is unclear whether the association between incarceration and mother’s distress is a result of her son’s incarceration or is related to broader family problems for which the incarceration is a proxy.

A further limitation is that findings depend on mothers’ report of incarceration, which may be underreported. Other limitations include lack of information about the length of the incarceration sentences (we would expect longer sentences to have a greater effect), the circumstances surrounding incarceration, the frequency of mother’s contact with the son before the incarceration, whether the incarcerated son had children, whether the mother incurred expenses as a result of the incarceration, and whether the son provided financial support to the mother before incarceration. Also, the results come from a single cohort from a specific neighborhood community in Chicago, and generalizability will depend on replications with other populations. Finally, our mediators were collected at the same time as mothers’ psychological well-being, and thus the time order could not be established. Alternative hypotheses are that financial difficulties and reports of greater grandparent burden may be results of mothers’ poor psychological well-being or that reciprocal relationships exist. In view of previous literature, we think our conceptualization is most plausible and consistent with the data but acknowledge there are alternative interpretations. Thus, results should be interpreted with caution and should be confirmed with replication in other data sets. Limitations should be addressed in future research.

Despite these limitations, we found an important association between the incarceration of a son and his mother’s psychological distress. This finding points out a key area in need of further investigation by family researchers, especially in light of the large number of incarcerated individuals in the United States, particularly in African American communities. Given the large number of individuals released from prison every year, efforts to protect a mother’s mental health and ensure her ability to assist her son’s transition back to the community may prove beneficial to individuals, families, and society (King, 1993; Visher & Travis, 2003).

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH52336, T32MH18834) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA06630). We wish to thank the Woodlawn community, the Woodlawn Project Board, and Sheppard Kellam, MD, for their support and cooperation in this project over many years. We also thank Kate Fothergill, PhD, for her thoughtful and valuable comments.

Contributor Information

Kerry M. Green, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Margaret E. Ensminger, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health*

Judith A. Robertson, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health*

Hee-Soon Juon, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health*.

References

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 5. Chicago: Small-Waters Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arditti JA, Lambert-Shute J, Joest K. Saturday morning at the jail: Implications of incarceration for families and children. Family Relations. 2003;52:195– 204. [Google Scholar]

- Avison WR, Turner RJ. Stressful life events and depressive symptoms: Disaggregating the effects of chronic strains and eventful stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1988;29:253– 264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JC, Morrow J, Mitteness LS. Gender, informal social support networks, and elderly urban African Americans. Journal of Aging Studies. 1998;12:199– 222. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173– 1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588– 592. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bonczar TP. Bureau of Justice Statistics special report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2003. Prevalence of imprisonment in the U.S. population, 1974–2001. (NCJ 197976) [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky SL. Families and friends of men in prison. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, Adams RG, Kellam SG. A longitudinal study of teenage motherhood and symptoms of distress: The Woodlawn community epidemiological project. Research in Community and Mental Health. 1981;2:183– 213. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM. Black grandparents rearing children of drug-addicted parents: Stressors, outcomes, and social service needs. Gerontologist. 1992;32:744– 751. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.6.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310– 357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comfort ML. In the tube of San Quentin: The “secondary prisonization” of women visiting inmates. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 2003;32:77– 107. [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Rueter MA, Conger RD. The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: The Family Stress Model. In: Crockett LJ, Silbereisen RK, editors. Negotiating adolescence in times of social change. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:486– 495. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demo DH, Acock AC. Singlehood, marriage, and remarriage: The effects of family structure and family relationships on mothers’ well-being. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:388– 407. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BS. Social status and stressful life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;28:225– 235. doi: 10.1037/h0035718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Juon HS. The influence of patterns of welfare receipt during the child-rearing years on later physical and psychological health. Women & Health. 2001;32:25– 46. doi: 10.1300/J013v32n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girshick LB. Soledad women: Wives of prisoners speak out. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, Kasper JD, Lafferty ME, editors. The women’s health and aging study. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging; 1995. (NIH Publication No. 95–4009) [Google Scholar]

- Hairston CF. Fathers in prison: Responsible fatherhood and responsible public policies. Marriage and Family Review. 2001;32:111– 135. [Google Scholar]

- Hairston CF. Prisoners and their families: Parenting issues during incarceration. In: Travis J, Waul M, editors. Prisoners once removed. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow CW. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 1998. Profile of jail inmates 1996. (NCJ 164620) [Google Scholar]

- Holzer HJ, Raphael S, Stoll MA. “Will employers hire former offenders?” Employer preferences, background checks, and their determinants. In: Patillo M, Weiman D, Western B, editors. Imprisoning America: The social effects of mass incarceration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. pp. 205–243. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540– 545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. Effects of parental incarceration. In: Gabel K, Johnston D, editors. Children of incarcerated parents. New York: Lexington; 1995. pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Branch JD, Agrawal KC, Ensminger ME. Mental health and going to school: The Woodlawn program of assessment early intervention, and evaluation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- King AE. The impact of incarceration on African American families: Implications for practice. Families in Society. 1993;74:145– 153. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RD, Ensminger ME, LaVeist TA. The responsibility continuum: Never primary, coresident and caregiver—Heterogeneity in the African-American grandmother experience. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2005;60:295– 304. doi: 10.2190/KT7G-F7YF-E5U0-2KWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:80– 94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF. Long-term stability of depression, anxiety, and stress syndromes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:520– 526. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A. Coping with stress: The case of prisoners’ wives. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984;46:699– 708. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A. Temporary single parenthood—The case of prisoners’ families. Family Relations. 1986;35:79– 85. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Roe KM, Price M. The physical and emotional health of grandmothers raising grandchildren in the crack cocaine epidemic. Gerontologist. 1992;32:752– 761. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.6.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Age and depression. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1992;33:187– 205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ. Bureau of Justice Statistics special report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2000. Incarcerated parents and their children. (NCJ 182335) [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AM. A metasynthesis: Mothering other-than-normal children. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12:515– 530. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:241– 256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Johnson J. Marital status, life strains and depression. American Sociological Review. 1977;42:704– 715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:151– 169. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. Sharing a residence with an adult child: A cause of psychological distress in the elderly. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61:144– 148. doi: 10.1037/h0079222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poe LM. Black grandparents as parents. Berkeley, CA: Author; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz DS. The increase in incarcerations among women and its impact on the grandmother caregivers: Some racial considerations. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 2002;29:179– 197. [Google Scholar]

- Sands RG, Goldberg-Glen RS. Factors associated with stress among grandparents raising their grandchildren. Family Relations. 2000;49:97– 105. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Pierce GR, Sarason BR. General and specific perceptions of social support. In: Avison WR, Gotlib IH, editors. Stress and mental health: Contemporary issues and prospects for the future. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 151–177. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422– 445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Extended family networks of older Black adults. Journal of Gerontology. 1991;46:210– 217. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.4.s210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis J, Waul M. Prisoners once removed: The children and families of prisoners. In: Travis J, Waul M, editors. Prisoners once removed. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Roszell P. Psychosocial resources and the stress process. In: Avison WR, Gotlib IH, editors. Stress and mental health: Contemporary issues and prospects for the future. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 179–210. [Google Scholar]

- Visher CA, Travis J. Transitions from prison to community: Understanding individual pathways. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:89– 113. [Google Scholar]

- Watts H, Nightengale D. Adding it up: The economic impact of incarceration on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of the Oklahoma Criminal Justice Research Consortium. 1996 Retrieved July 28, 2003, from http://www.doc.state.ok.us/docs/ocjrc/ocjrc96/ocjrc55.htm.