ABSTRACT

Objective:

to validate an instrument to identify situations that trigger moral distress in relation to intensity and frequency in primary health care nurses.

Method:

this is a methodological study carried out with 391 nurses of primary health care, applied to the Brazilian Scale of Moral Distress in Nurses with 57 questions. Validation for primary health care was performed through expert committee evaluation, pre-test, factorial analysis, and Cronbach’s alpha.

Results:

there were 46 questions validated divided into six constructs: Health Policies, Working Conditions, Nurse Autonomy, Professional ethics, Disrespect to patient autonomy and Work Overload. The instrument had satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha 0.98 for the instrument, and between 0.96 and 0.88 for the constructs.

Conclusion:

the instrument is valid and reliable to be used in the identification of the factors that trigger moral distress in primary care nurses, providing subsidies for new research in this field of professional practice.

Descriptors: Validation Studies, Nurses, Primary Health Care, Ethics, Stress Psychological, Moral

Introduction

Moral distress (MD) has been discussed for more than three decades since in 1984 the first concept of moral distress in nursing was presented. Identified as a psychological imbalance caused by the failure to perform an action viewed as morally correct, due to institutional barriers, managerial reluctance, lack of human and material resources, among others 1 .

In the 2000s, moral distress was related to the situation when a nurse is unable to perform an action, the psychological responses are triggered and presented in the work environment 2 . Since then, the concept has undergone changes and extensions by researchers from different parts of the world.

As a theoretical reference supporting this study, the extension of the concept proposed in Brazil was adopted, whereby moral distress is identified as a procedural phenomenon and at the same time a unique experience that integrates the ethical and moral experience of the subject. In this perspective, the moral distraction encompasses elements articulated from the ethical experience of each human being, such as the moral problem, moral uncertainty, moral sensibility, moral deliberation and moral professional ethical skills. The MD or moral suffering is considered as the interruption or failure of the process of moral deliberation and not only by its negative consequences but in its productivity or potential to propel and promote the development of moral skills, reflexivity, and resources for deliberation 3 .

A pioneer scale was developed in the North American context between 1994 and 1997 4 , to verify the triggering factors and to infer the intensity and frequency of moral distress. The Moral Distress Scale (MDS) contained 32 items on a Likert scale from 1 to 7, where 1 is never frequent/none and 7 is very frequent/very intense, as commonly used in psychometric studies, that is, to measure attitudes or behaviors, such as the case of MDS. The first version of MDS was applied to 214 hospital nurses (working in intensive and occupational units), showing moderate levels of moral distress in these professionals 4 - 5 .

A second MDS application containing 38 questions was performed with 106 nurses from medical and surgical units at two American hospitals to assess the intensity and frequency of moral distress. It was pointed out the cause “to work with levels of personnel that I consider to be insecure” as greater frequency and intensity and “to respond to the patient´s request for assistance to euthanasia when the patient has a poor prognosis” as lower frequency and intensity of moral distress 6 .

In Brazil, the MDS was translated and validated in its original form for the first time in 2009, containing 38 questions, and 21 questions validated by the application in 136 hospital nurses 7 . This validation obtained results similar to the application of MDS in the American scenario, with the factor of greater intensity and frequency 20 “lack of competence of the work team” 6 .

In 2012, the same author expanded his research by adapting MDS to the Brazilian context, since he realized that many situations of moral distress already observed in this scenario were not sufficiently contemplated in the original version, adding and validating another thirteen questions, where 23 questions were validated of a total of 39, with other nursing professionals, such as technicians and nursing assistants, in two hospitals in the south of Brazil. The second research also revealed the “lack of competence of the work team” with the greatest intensity and frequency of moral suffering 8 .

Since then, in several scenarios in the world context, MDS has been applied, reviewed and expanded 9 - 11 . Its last MDS-Revised or MDS-R version is structured with 22 items on a Likert scale from 0 to 4 for frequency and intensity, where 0 is never frequent/no intensity and 4 is very frequent/very intense 9 . However, it has its orientation to the hospital scope, and although it is broadened and validated in the Brazilian hospital scenario 7 - 8 , it is limited to the other scenarios of professional nurse performance.

Given the breadth and specificity of the Brazilian scenario and specifically the configuration of Primary Health Care (PHC) and the nurse’s performance in this scenario, it is imperative to investigate the moral distress in this perspective. Thus, the objective of this study was to validate a Brazilian instrument to identify the intensity and frequency of situations triggering moral distress in primary care nurses.

Methods

This is a methodological study of adaptation and validation of the Brazilian Scale of Moral Distress in Nurses, for PHC nurses, for the inexistence of specific instruments for this purpose and scenario. The Brazilian Scale of Moral Distress in Nurses was elaborated by researchers from three federal universities in Brazil between 2014 and 2015, following the steps for their elaboration: 1) elaboration and application of a Survey with 711 nurses working in different health care scenarios in different regions of Brazil; 2) Analysis of the Survey and elaboration of initial categories to construct the questions of the instrument; 3) Carrying out a comprehensive literature review on national and international databases, matching the findings of the Survey; 4) Elaboration of the first version of the instrument; 5) Validation of the instrument by experts and pre-test; 6) Final version of the instrument containing 57 questions on a Likert scale from 0 to 6 for intensity and frequency (0 - never/none and 6 - very frequent/very intense); 7) Application of the instrument with nurses working in all contexts of Brazilian health care through an electronic form goodle.docs 12 .

The Brazilian Scale of Moral Distress in Nurses was applied in a total of 1,226 nurses from different health care settings, 391 were in the scope of PHC being the objects of this study. This study was carried out in accordance with the international recommendations for elaboration and validation of questionnaires, following eight steps 13 , including content, criterion and construct validation, described below.

In the first step, on a clear determination of what will be measured 13 , an integrative review on moral distress was performed in PHC to identify its characteristics and trigger factors in this scenario. The search was performed in the Virtual Health Library, in all its databases, from July to August 2015 through the descriptors Nursing and Primary Health Care using the term “AND” and temporal cut from 2006 for the institution of the National Policy of Primary Care (PNAB) by ordinance 648/2006. The choice of broad descriptors for the study focus is due to the inexistence of specific descriptors and the lack of knowledge about the subject, to enable to seek results in studies that interface with the phenomena.

There were 411 publications selected and 21 of them were selected according to established criteria, that is, they contain the descriptors in the abstract and/or title, in Portuguese and published from 2006. The analysis of the articles was carried out from the three stages of the Content Analysis: pre-analysis, material exploration and material interpretation 14 . In the end, it came in three main categories: Work Organization, Working Conditions, and Professional/Personal Relationships, pointing out the dynamism in the relationships among staff, among patients and with health education activities.

The second step, elaboration of a set of items 13 was carried out from the integrative review, in which the categories elucidated helped in the evaluation of the specific issues of moral distress in the work of the nurse in PHC. At that moment, each of the 55 questions of the original instrument was analyzed, evidencing that all were present in the literature and pointed to situations triggering moral distress in PHC. However, two gaps have been identified, one in the social vulnerabilities and the other in the educational practices under the PHC. As a result of these shortcomings, two questions were inserted that included: “Recognizing that educational actions with the patient are insufficient” and “Feeling unable to defend the patient in situations of social vulnerability”. Thus, the adaptation of the instrument contemplated the 55 original questions and two more questions elaborated from the identification of gaps on the PHC, totaling 57 questions.

In the third step, the measurement format 13 was determined, and two Likert six-point scales were maintained, according to the original instrument, one measuring the intensity of MD ranging from 0 (none) to 6 (for very intense suffering), and the other by measuring the frequency with which MD conditions occur, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (very common).

The fourth step consisted of a review of the set of items by specialists 12 , considering the validity of face and content. At that moment, the questions were evaluated for the language used, if they were also comprehensible by nurses of the PHC and evaluated for the representation of the content that was wanted to be analyzed. Thus, it was evaluated by an expert board composed of one expert from PHC and two from nursing ethics; and then a pre-test with 30 nurses from different Brazilian states was performed, to have acted or to be working for a minimum period of six months in the PHC as an inclusion criterion. After these validations, the instrument was considered approved to be applied in the context of PHC and in other scenarios.

The fifth step refers to the consideration of inclusion of validation items 13 , in which separately validated items can be attached to the instrument, but it was chosen to validate the items together after the final constitution of the scale. To complement the MD assessment in the PHC, some socio-demographic and labor variables were included at the beginning of the instrument, such as gender, age, country, time of action, training time, number of links, complementary training, places of work, nature of the link and workload.

In the sixth step, administration of the items in a sample 13 , the instrument was applied in a sample of the population of interest, that is, the site comprised the Brazilian PHC. Thus, all modalities of PHC teams were incorporated.

According to data from the National Register of Health Establishments of Brazil (CNES), Brazil has 50,165 health teams belonging to the PHC. The number stratified by region and the number of nurses per region are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Quantitative nurses and primary care nurses in the Brazilian regions, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil, 2017.

| Region | Health Establishment | Nurses |

| Northeast | 18.407 | 17.038 |

| Southeast | 16.502 | 23.602 |

| South | 7.315 | 9.220 |

| North | 4.460 | 4.634 |

| Midwest | 3.481 | 4.542 |

| Total | 50.165 | 59.036 |

A simple random sampling was defined for the study, based on the selection of a random sample of a population, used when a population is believed to be homogeneous, as in the case of this study 15 . Nurses with a minimum of six months’ work in the PHC were included.

However, to avoid possible biases in relation to the sample size, a minimum sample calculation was performed, as follows:

In which:

n = sample size

X² = Chi-square value for 1 degree of freedom at the confidence level of 0.05 and equal to 3.89 (predetermined fixed value).

N = population size

P = proportion of the population to be estimated (it is assumed to be 0.50 since this proportion would provide the maximum sample size)

d = degree of precision expressed in proportion (0,05)

Considering a population of 59,036 PHC nurses, a minimum sample of 383 participants was estimated.

Emails were sent to nurses all over Brazil with information about the research and the access link. Invitations were also sent to the health secretariats of the Brazilian states and social support was used to publicize the research and form of participation. The data were collected online through the application of the instrument via Google.docs from November 2015 to April 2016. At the end of the data collection, the sample consisted of a total of 391 participants in the PHC who answered the instrument in the period of data collection.

In the seventh step, corresponding to the evaluation of items 13 two statistical tests were carried out to guarantee to construct validity after the application of the scale in the selected sample: factorial analysis, and internal consistency analysis using Cronbach’s alpha. In the factorial analysis, the grouping of constructs of the questions by their factorial load and verification of the commonality was done, defining orthogonal rotation Varimax as a method of extraction of analysis of the main components. The formation of the constructs was established according to two criteria: the degree of association between the variables, found through factorial loads (> 500), and their conceptual association.

Cronbach’s alpha evaluated the level of reliability of the questions through the characteristics of each question in the different constructs, verifying if they were consistent with the phenomenon researched.

Finally, in the eighth and final step, optimizing the length of the scale 13 , it is possible, to exclude some item from the formed factors after factorial analysis and internal consistency to increase the reliability of the instrument. However, since all factors presented satisfactory Cronbach´s alpha values, no exclusions were made after the factorial analysis.

This research was the multicenter macro-project entitled: The process of moral distress/suffering in nurses in different health work contexts, being submitted to the Research Ethics Committees with Human Beings of the three Universities involved, with the following final opinions: 602.598-0 of 10/02/2014 (Federal University of Santa Catarina/UFSC); 602.603-0 of 01/31/2014 (Federal University of Minas Gerais/UFMG) and 511.634 of 01/17/2014 (Federal University of Rio Grande/FURG). The ethical aspects were respected according to Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council.

Results

Regarding the characterization of the study participants, there were 368 (93.9%) female and 23 (5.9%) male, 65 (16.6%) aged 20 to 29 years old, 150 (38.3%) from 30 to 39 years old, 99 (25.3%) from 40 to 49 years old and 77 (19.6%) with 50 or more. Regarding the training time, 7 (1.8%) had less than 1 year, 98 (25%) had from 1 to 5 years, 111 (28.3%) had from 6 to 10 years, 76 (19.4%) had 11 to 15 years, 31 (7.9%) had from 16 to 20 years and 65 (16.6%) with more than 20 years and 3 (0.7%) did not respond to this question.

Also, complementary training was also analyzed, with 53 (13.5%) not having any complementary training, 34 (8.7%) with training, 258 (65.8%) specialization, 41 (10.5%) Master´s degree, and 5 (1.3%) with Ph.Ds. Regarding the number of links, there were 280 (71.4%) with 1 link, 94 (24.04%) with 2 links and 17 (4.3%) did not respond.

Regarding the time of performance, 190 (48.5%) were working for 5 years in the service, 89 (22.7%) from 6 to 10 years, 56 (14.3%) from 11 to 15 years, 20.1%) from 16 to 20 years and 35 (8.9%) for more than 20 years, one participant (0.2%) did not respond to this question. The workload was represented by 9 (2.3%) who operated up to 20 hours, 67 (17.1%) from 21 to 30 hours, 232 (59.2%) from 31 to 40 hours and 83 (21.2 %) more than 40 hours per week. The local variables of action and type of bond correspond to 100% of the participants since the sites were all of primary health care and of a public character.

Regarding the region of action, 20 participants (5.1%) were from the North region, 66 (16.9%) from the Northeast region, 163 (41.7%) from the Southeast region, 100 (25.5%) from the South region, 24 (6.1%) from the Center-West region and 18 (4.7%) did not respond to this item. It is noted the great majority of respondents from the Southeast region. The expressive participation is explained by the fact that this region has the second largest number of teams working in the PHC, with a total of 15,637 teams, according to data from the National Registry of Health Teams. On the other hand, the Northeast has the largest number of teams of the PHC with a total of 16,903, and it was the third region with the largest participants in the study.

Regarding the construct validity, this was accomplished through the exploratory factorial analysis, with Varimax rotation with the 57 questions of the instrument (between blocks), seeking to verify the discriminant validity. The first grouping suggested 8 constructs, but with grouping difficulty due to the low factorial load and low commonality between the questions.

The process of exclusion of the questions was then initiated by the criterion of inferior commonality <0.500 in the block and lower factor load <0.500 in the constructs. At the end of the analysis, there were 11 questions excluded and 6 constructs were formed, representing 71% of the variation of the original questions, evidencing an adequate degree of data synthesis.

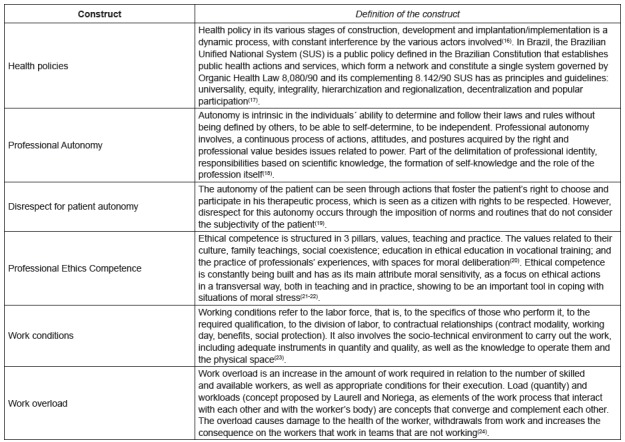

The reliability of the 6 constructs was tested by Cronbach’s Alpha applied to each construct separately and after the final instrument. Construct 1 obtained Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.96, 2 of 0.93, 3 of 0.92, 4 of 0.93, 5 of 0.94 and 6 of 0.88. The final instrument obtained Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.98. The high number of this marker indicates the reliability of the scale in the selected sample. The final version of the instrument consisted of six constructs consisting of 46 items (Table 2 and Table 3) and described conceptually (Figure 1), and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test of Barllet’s sampling adequacy and sphericity was presented (Table 4 ).

Table 2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (Varimax rotation) of the instrument of moral distress in primary care nurses, presentation of two constructs. Florianópolis, SC, Brazil, 2017.

| Rotary component matrix * | |||||||

| Indicators† | Components‡ | ||||||

| Health policies | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | |

| 29. To recognize that the demands of continuity of patient/user care are not met | 757 | 237 | 198 | 199 | 267 | 197 | |

| 30. To recognize the lack of resolution of health actions due to social problems | 727 | 219 | 182 | 172 | 307 | 188 | |

| 32. To recognize that educational actions with the patient are insufficient | 723 | 253 | 202 | 151 | 211 | 197 | |

| 28. To recognize that the patient´s hosting is inappropriate | 699 | 265 | 250 | 187 | 218 | 159 | |

| 33. To experience on the humanized care practices advocated by public policies | 651 | 307 | 333 | 202 | 264 | 156 | |

| 27. To recognize insufficient access to the service for the patient | 637 | 218 | 231 | 172 | 400 | 104 | |

| 31. To recognize the lack of resolution of health actions due to the poor quality of care | 632 | 209 | 359 | 240 | 251 | 194 | |

| 37. To recognize impairments to care due to inadequate integration between services/sectors | 624 | 253 | 314 | 154 | 284 | 207 | |

| 34. To recognize routines and practices that are unsuitable for professional safety | 552 | 265 | 350 | 182 | 271 | 212 | |

| 35. To recognize routines and practices that are inappropriate for patient safety | 545 | 218 | 457 | 238 | 219 | 097 | |

| 44. To experience the suspension and postponement of procedures for reasons that are contrary to the needs of the patient/user | 501 | 261 | 480 | 185 | 309 | 104 | |

| Professional Visibility/Nurse Autonomy | |||||||

| 47. Feeling disrespected by hierarchical superiors | 187 | 746 | 277 | 187 | 180 | 075 | |

| 17. Feeling discriminated against by other professionals | 309 | 681 | 003 | 265 | 107 | 083 | |

| 48. To recognize ethically incorrect attitudes of managers or superiors | 298 | 639 | 277 | 175 | 331 | 112 | |

| 38. To have their autonomy limited in the decision of specific behaviors of the nursing team | 197 | 638 | 305 | 205 | 210 | 185 | |

| 18. Feeling devalued compared to other professionals | 372 | 625 | 007 | 273 | 025 | 145 | |

| 41. To recognize situations of offense to the professional | 245 | 623 | 311 | 173 | 251 | 295 | |

| 39. To experience conflicting relationships regarding the attributions of health team members | 295 | 591 | 284 | 149 | 243 | 284 | |

| 49. Feeling pressured to agree or silence against fraud on behalf of the institution | 074 | 560 | 436 | 177 | 123 | 075 | |

| 40. Working under pressure for insufficient time to reach goals or perform tasks | 331 | 557 | 230 | 072 | 142 | 406 | |

| 42. To recognize situations of disrespect to the professional’s privacy | 159 | 538 | 416 | 207 | 228 | 288 | |

*Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Standardization. a. Converted rotation in 10 iterations.

† Indicators, indicating the issues of the instrument with their respective numbering.

‡ Components, indicating the value (intensity) of each construct (C1 to C6).

Table 3. Exploratory Factorial Analysis (Varimax rotation) of the instrument of moral distress in primary care nurses, presentation of four constructs. Florianópolis-SC, Brazil, 2017.

| Rotary component matrix * | |||||||

| Indicadotors† | Components‡ | ||||||

| Right to Health/Disrespect for patient autonomy | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | |

| 55. To recognize situations of disrespect to the patient’s right to confidentiality/secrecy | 153 | 153 | 781 | 285 | 122 | 107 | |

| 54. To recognize situations of disrespect to the patient’s right to privacy/privacy | 270 | 206 | 758 | 215 | 221 | 024 | |

| 56. To recognize situations of disrespect to patients ‘and family members’ right to information | 289 | 209 | 757 | 208 | 131 | 110 | |

| 46. To experience care behaviors that disregard patients’ beliefs and culture | 244 | 151 | 697 | 165 | 145 | 072 | |

| 45. To experience or participate in unnecessary care behaviors to the patient/user’s conditions/needs | 270 | 234 | 634 | 194 | 148 | 159 | |

| 53. To recognize situations of disrespect/maltreatment by professionals in relation to the patient | 385 | 223 | 599 | 297 | 181 | 120 | |

| Professional Ethics Competence | |||||||

| 24.To experience the recklessness by the nurse | 066 | 282 | 365 | 719 | 160 | 048 | |

| 22. To experience the recklessness by the doctor | 251 | 250 | 161 | 701 | 142 | 094 | |

| 4. To work with unprepared doctors | 277 | 090 | 100 | 656 | 311 | 324 | |

| 23. To experience the omission by the nurse | 145 | 265 | 408 | 651 | 144 | 054 | |

| 21. To experience the omission by the doctor | 340 | 210 | 224 | 627 | 133 | 218 | |

| 5. Work with unprepared nurses | 153 | 074 | 254 | 590 | 184 | 459 | |

| 25. To experience the omission by professionals of other categories | 174 | 443 | 328 | 590 | 233 | 010 | |

| 26. To experience the recklessness by professionals from other categories | 152 | 409 | 314 | 574 | 244 | 009 | |

| Work conditions | |||||||

| 14. To recognize that the available permanent equipment/materials are inadequate | 313 | 175 | 242 | 192 | 733 | 196 | |

| 11. To recognize that consumer materials are insufficient | 315 | 245 | 152 | 195 | 722 | 211 | |

| 13. To recognize that the available permanent equipment/materials are insufficient | 311 | 248 | 246 | 152 | 721 | 259 | |

| 16. To recognize that the physical structure of the service is inadequate | 300 | 180 | 161 | 246 | 691 | 165 | |

| 12. To recognize that consumer materials are inadequate | 275 | 182 | 221 | 247 | 687 | 255 | |

| 15. To recognize that the physical structure of the service is insufficient | 324 | 194 | 153 | 246 | 650 | 191 | |

| Work overload | |||||||

| 1. To work with insufficient number of professionals to demand | 256 | 346 | 098 | 064 | 259 | 657 | |

| 3. To experience work overload conditions | 274 | 425 | 034 | 131 | 275 | 621 | |

| 2. Incomplete multiprofessional health team | 297 | 253 | 105 | 137 | 350 | 620 | |

| 6. To work with unprepared nursing assistants and technicians | 153 | 057 | 210 | 516 | 204 | 614 | |

| 7.To work with professionals from other unprepared categories | 198 | 104 | 099 | 497 | 299 | 535 | |

*Método de Rotação: Varimax com Normalização de Kaiser.

a. Converted rotation in 10 iterations.

† Indicators, with the questions of the instrument and their respective numbering.

‡ Components, with the value (intensity) of each construct (C1 to C6).

Figure 1. Conceptual presentation of the constructs constituted by the factorial and Cronbach´s Alpha analysis. Florianópolis, SC, Brazil, 2017.

Table 4. Test of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett*. Florianópolis - SC, Brazil, 2017.

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling suitability. | .958 |

| Bartlett sphericity test | 15908.435 |

| Approx. Chi-square df | 1035 |

| Sig. | .000 |

* Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s test of sampling suitability and Barllet’s sphericity.

Table 2 shows that the two constructs called Health Policies and Professional Visibility/Autonomy of the Nurses presented high factor loads > 500, with the highest factor load of 757 in question 29. To recognize that the demands of continuity of patient/users are not met in the Health Policy construct and the second with 746 in question 47. Feeling disrespected by hierarchical superiors of the Professional Visibility/Autonomy of the Nurse construct.

Table 3 shows the representativity of the other constructs constituted by the factorial load > 500. However, they varied between the largest load of 781 in question 55. To recognize situations of disrespect to the patient´s right to the confidentiality/secrecy of the construct Right to Health/Disrespect to patient´s autonomy, and the value of 657 in question 1. Working with an insufficient number of professionals to demand in the Work Overload construct.

Table 4 represents the reliability of the factorial analysis, when the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measurement of sampling adequacy is between 0.5 and 1.0, proving that the factorial analysis was adequate. In the case of the study, this measure was close to 1.0 (0.958) proving the adequacy of the factorial analysis.

After the trustworthiness and reliability of the instrument were verified, the theoretical construction of the constructs was started, which is represented in Figure 1.

Discussion

Moral distress in the context of primary health care, especially in the Brazilian scenario, is still a phenomenon with innumerable gaps to be explored. The validation of this instrument allows some of these gaps to be visualized and discussed to identify the factors that trigger moral distress.

The first version of the Moral Distress Scale (MDS) pointed to the validation of 3 factors, the first related to the individual responsibility of the nurse, the second not performing what would be the best for the patient, and the third to deceive, go against their values and beliefs 4 . These three factors were the same as those adopted for the application of MDS in other studies 6 .

Other researchers have reduced MDS to 21 items and applied it to physicians and nurses working in intensive care units, presenting in their analysis a difference between these professional categories in which it is appropriate to adopt treatment postures that affect the patient without any indication 25 .

Other authors have adapted MDS and/or developed other scales or surveys to measure concepts similar to moral distress in other cultures or populations 11 , 26 - 32 . The MDS was reviewed and applied in other scenarios and other professional categories, called MDS-Revised, but also with the analysis of the initial 3 factors of MDS 9 .

In the Brazilian context, in its first version of adaptation and validation of MDS, there were 4 factors identified, grouped by factorial load and conceptual coherence: 1) Denial of the role of the nurse as a patient’s lawyer; 2) Lack of competence in the work team; 3) Disrespect for patient autonomy; 4) Therapeutic Obstination (TO) 7 . In another MDS extension and validation study for all nursing categories, there were 5 constructs validated: lack of competence in the work team; disrespect for patient autonomy; insufficient working conditions; denial of the nursing role as the patient’s lawyer in the terminal; denial of the role of nursing as a patient’s lawyer 8 .

The instrument validated for primary care nurses is characterized by 6 constructs. From these constructs, “Health policies” and “Professional ethical competence” are presented as new elements in the identification of the factors that trigger moral distress.

The first construct “Health Policies” presented the largest Cronbach´s Alpha with 0.959, followed by “Working Conditions” with 0.942, “Autonomy of the Nurse” with 0.932, “Professional ethical competence” with 0.926, “Disrespect for patient´s autonomy” with 0.924 and “Workload” with 0.881.

The first construct presents questions related to patient´s access, care, continuity of care, resolution of actions, educational practices, humanized care, patient and professional safety. These questions are immersed in health policies, especially when there is a universal health system, which emphasizes equity, equality, completeness, resolve, social participation, regionalization, decentralization, and hierarchization 17 .

The second construct Working Conditions addresses situations that emerge from the deficiency of physical structures, equipment, materials and human resources. They are seen in different scenarios of the context of the nurse and allied to the low remuneration, to the increase of the work day and rigid hierarchy in the health team strengthen the generation of psychological suffering and poor quality of care 23 - 24 , 30 - 32 .

The third construct Autonomy of the Nurse was constituted of elements related to professional visibility, limitation in decision making, conflicts with other members of the health team for decision making and disrespect by superiors regarding conduct and professional privacy. The search for professional autonomy should be based on the delimitation of its scientifically based knowledge, as well as on the professional’s attitude towards the problems presented in their reality 33 .

The lack of autonomy and the devaluation of the nurse professional are factors that have been shown to trigger moral distress in other international settings, in which these factors are influenced by the position of other team members regarding the nurses’ conduct and the institutional rules imposed on them 34 .

The fourth construct Professional ethical competence was formed by situations that presented the omission, recklessness, and unpreparedness of nurses and other professional categories regarding health practices. The scenario in which these professionals work is constantly changing in terms of organizational, technological or workload, implying a constant ethical action 35 . It is in this scenario that (re) builds the ethical competence of each professional, from the moment he has problems, he assumes responsibility and builds his action based on values and beliefs, allied to his scientific knowledge and professional experience 20 - 21 .

The fifth construct Disrespect for patient´s autonomy grouped elements derived from patient´s right to privacy, choice of conduct, secrecy, access to information, devaluation of beliefs and cultures, and unnecessary conduct of care. The recognition of the singularity, individuality, completeness, legitimacy, freedom, choices of treatments and services by the patient is still incipient in the health professional’s view, participation in their therapeutic process and their right to choose, rights that must be respected for a performance of the patient 19 .

The last construct Work Overload has integrated imminent issues of insufficient human resources and disqualified human resources as factors that increase workload. Overworking due to such elements together with adverse working conditions tends to cause harm to the health of professionals, resulting in an increase in the lack of human resources, and consequently an increase in workload for those who remain in the service 23 - 24 . Evaluation and quality of care are interfered with by work overload, compromising patient safety, and consequently the trigger for experiencing moral distress 31 - 32 .

Thus, the 6 constructs validated 46 of the 57 questions of the instrument for the primary care sample, obeying the statistical and conceptual criteria.

Conclusion

The results show that the instrument is able to identify the factors that trigger moral distress in nurses of primary care, providing subsidies for new research in this field of professional practice. It was possible to identify 6 constructs that exemplify the factors triggering moral distress: Health Policies, Working Conditions, Nurse Autonomy, Professional ethics, Disrespect to patient´s autonomy and Work Overload.

The validation of the instrument was supported by the analysis of factorial load and commonality greater than 0.500 and Cronbach’s Alpha <0.800 in the constructs found, considering the valid instrument for the Brazilian context of primary care, providing relevant information about the studied phenomenon. However, this study had as limitations the fact that it was the first applied and validated in the context of the primary care, which hindered to establish greater comparisons.

It is expected that the findings of this research contribute to the establishment of new discussions in the field of nursing ethics in primary care, especially in the creation of strategies that strengthen the nurse’s performance, and in the improvement of actions that promote the transformation of the actions in health.

Footnotes

Sponsorship: Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq.

References

- 1.Jameton A. A reflection on moral distress in nursing together with a current application of the concept. J Bioeth Inq. 2013;10(3):297–308. doi: 10.1007/s11673-013-9466-3. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11673-013-9466-3 http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11673-013-9466-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corley MC. Nurse moral distress a proposed theory and research agenda. Nurs Ethics. 2002;9(6):636–650. doi: 10.1191/0969733002ne557oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos FRS, Barlem ELD, Brito MJM, Vargas MA, Schneider DG, Brehmer LCF. Conceptual framework for the study of moral distress in nurses. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2016;25(2):e4460015. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/tce/v25n2/0104-0707-tce-25-02-4460015.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072016004460015 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corley MC, Elswick RK, Gorman M, Clor T. Development and evaluation of a moral distress scale. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(2):250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2001.01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mccarthy J, Gastmans C. Moral distress: A review of the argument-based nursing ethics literature. Nurs Ethics. 2015;22(1):131–152. doi: 10.1177/0969733014557139. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0969733014557139 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0969733014557139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corley MC, Minick P, Elswick RK, Jacobs M. Nurse Moral Distress and Ethical Work Environment. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12(4):381–390. doi: 10.1191/0969733005ne809oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlem ELD, Lunardi VL, Lunardi GL, Dalmolin GL, Tomaschewski JG. The experience of moral distress in nursing: the nurses' perception. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2012;46(3):681–688. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342012000300021. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reeusp/v46n3/en_21.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342012000300021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barlem ELD, Lunardi VL, Lunardi GL, Tomaschewski-Barlem JG, Almeida AS. Psycometric characteristics of the Moral Distress Scale in Brazilian nursing professionals. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2014;23(3) http://www.scielo.br/pdf/tce/v23n3/pt_0104-0707-tce-2014000060013.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072014000060013 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG. Development and Testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in healthcare professional. AJOB Prim Res. 2012;2(3):1–9. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21507716.2011.652337?scroll=top&need Access=true http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21507716.2011.652337 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silén ML, Svantesson M, Kjellström S, Sidenvall B, Christensson L. Moral distress and ethical climate in a Swedish nursing context: perceptions and instrument usability. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:3483–3493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03753.x. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.136702.2011.03753.x/abstract;jsessionid=9BEB2D604618063B77103D87A68246D0.f04t03 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauly BL, Varcoe C, Storch J, Newton L. Registered Nurses' Perceptions of Moral Distress and Ethical Climate. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16:561–573. doi: 10.1177/0969733009106649. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0969733009106649?url_ver=Z39.882003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0969733009106649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos FRS, Barlem EDL, Brito MJM, Vargas MA, Scheneider DG, Brehmer LFC. Construction of the Brazilian Scale of Moral Distress in nurses - a methodological study. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2017;26(4):e0990019. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/tce/v26n4/en_0104-0707-tce-26-04-e0990017.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072017000990017 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manganello JA, Devellis RF, Davis TC, Schottler-Thal C. Development of the Health Literacy Assessment Scale for Adolescents (HAS-A) 2015;8(3):172–184. doi: 10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000016. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000016?scroll=top&needAccess=true https://doi.org/10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Câmara RH. Content analysis: from theory to practice in social research. Gerais: Rev Interinstitucional Psicol. 2013;6(2):179–191. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/gerais/v6n2/v6n2a03.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szwarcwald CL, Damacena GN. Complex Sampling Design in Population Surveys: Planning and effects on statistical data analysis. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2008;11:38–45. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepid/v11s1/03.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1415-790X2008000500004 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giovanella L, Santos AM. Regional governance: strategies and disputes in health region management. Rev Saúde Pública. 2014;48(4):622–631. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005045. http://www.journals.usp.br/rsp/article/view/85711/88476 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos NR. The Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS), State Public Policy: Its institutionalized and future development and the search for solutions. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2013;18(1):273–280. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232013000100028. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v18n1/28.pdf. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232013000100028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalinowski CE, Martins VB, X FRG, Neto, Cunha ICKO. Professional autonomy in primary health care: na analysis of nurses' perception. SANARE. 2012;11(1):6–12. https://sanare.emnuvens.com.br/sanare/article/view/260/233 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva AM, Sá MC, Miranda L. Concepts of subject and autonomy in humanization of healthcare: a literature review of experiences in hospital service. Saude Soc. 2013;22(3):840–852. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/sausoc/v22n3/17.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-12902013000300017 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaefer R, Jungues JR. The construction of ethical competence in the perception of primary care nurses. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2014;48(2):329–334. doi: 10.1590/s0080-6234201400002000019. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reeusp/v48n2/pt_0080-6234-reeusp-48-02-329.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420140000200019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renno HMS, Ramos FRS, Brito MJM. Moral distress of nursing undergraduates Myth or reality? Nurs Ethics. 2016;18:1–9. doi: 10.1177/0969733016643862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trindade LL, Pires DEP. Implications of primary health care models in workloads of health professionals. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2013;22(1):36–42. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S010407072013000100005&lng=en http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-07072013000100005 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pires DEP, Machado RR, Soratto J, Scherer MA, Gonçalves ASR, Trindade LL. Nursing workloads in family health: implications for universal access. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2016;24(e2682):1–9. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.0992.2682. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v24/pt_0104-1169-rlae-0992-2682.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.0992.2682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmoeller R, Trindade LL, Neis MB, Gelbcke FL, Pires DEP. Nursing workloads and working conditions integrative review. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2011;32(2):368–377. doi: 10.1590/S1983-14472011000200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patientsin intensive care units Collaboration, moral distress,and ethical climate. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):422–429. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254722.50608.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radzvin LC. Moral distress in certified registered nurse anesthetists: Implications for nursing practice. AANA J. 2011;79(1):39–45. https://www.aana.com/newsandjournal/Documents/moraldistress_0211_p39-45.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borhani F, Mohammadi S, Roshanzadeh M. Moral distress and perception of futile care in intensive care nurses. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2015;8(2) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4733540/?report=reader [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiggleton C, Petrusa E, Loomis K, Tarpley J, Tarpley M, O'Gorman ML, Miller B. Medical students' experiences of moral distress: Development of a web-based survey. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):111–117. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c4782b. https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=20042836 http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c4782b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O´Connell CB. Gender and the experience of moral distress in critical care nurses. Nurs Ethics. 2015;22(1):32–42. doi: 10.1177/0969733013513216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulrich C, O'Donnell P, Taylor C, Farrar A, Danis M, Grady C. Ethical climate, ethics stress, and the job satisfaction of nurses and social workers in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(8):1708–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veer AJE, Francke AL, Struijs A, Willems DL. Determinants of moral distress in daily nursing practice a cross sectional correlational questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf LA, Perhats C, Delao AM, Moon MD, Clark PR, Zavotsky KE. "It's a burden you carry": describing moral distress in emergency nursing. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2015.08.008. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S009917671500330X?via%3Dihub http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos FOF, Montezelli JH, Peres AM. Professional autonomy and nursing care systematization the nurses' perception. Rev Min Enferm. 2012;16(2):251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dyoa M, Kalowesb P, Devries J. Moral distress and intention to leave a comparison of adult and paediatric nursesby hospital setting. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2016;36:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaefer R, Vieira M. Ethical competence as a coping resource for moral distress in nursing. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2015;24(2):563–573. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/tce/v24n2/pt_0104-0707-tce-24-02-00563.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072015001032014 [Google Scholar]