Abstract

Restraint and binge eating are cognitive and behavioral processes that are particularly important in the context of obesity. While extensive research has focused on negative affect (NA) in relation to binge eating, it is unclear whether affective valence (i.e., positive versus negative) and stability (i.e., state versus trait) differentially predict binge eating and restraint among individuals with obesity. Distinguishing between valence and stability helps elucidate under which affective contexts, and among which individuals, restraint and binge eating are likely to occur. Therefore, the present study examined relationships between trait and state levels of NA and positive affect (PA), binge eating, and restraint intention among 50 adults with obesity (BMI ≥ 30). Participants completed baseline assessments followed by a two-week ecological momentary assessment (EMA) protocol. Structural equation modeling assessed a trait model of person-level measures of affect in relation to overall levels of binge eating and restraint intention, while general estimating equations (GEEs) assessed state models examining relationships between momentary affect and subsequent binge eating and restraint. The trait model indicated higher overall NA was related to more binge eating episodes, but was unrelated to overall restraint intention. Higher overall PA was related to higher overall restraint intention, but was unrelated to binge eating. State models indicated momentary NA was associated with a greater likelihood of subsequent binge eating and lower restraint intention. Momentary PA was unrelated to subsequent binge eating or restraint intention. Together, findings demonstrate important distinctions between the valence and stability of affect in relationship to binge eating and restraint intention among individuals with obesity. While NA is a more salient predictor of binge eating than PA, both overall PA and momentary NA are predictors of restraint intention.

Keywords: obesity, affect, dietary restraint, binge eating, ecological momentary assessment

Affective disturbances, particularly negative affect (NA), have been broadly implicated in the onset and maintenance of binge eating and obesity (Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011; Leehr et al., 2015). In addition, ED behaviors are prevalent among individuals who are obese (Hilbert, De Zwaan, & Braehler, 2012), and binge eating may contribute to weight gain in this population (Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Haines, Story, & Eisenberg, 2007; Yanovski, 2003). Furthermore, individuals who are obese may have difficulty adhering to dietary interventions due to affective disturbances and emotion regulation difficulties (Carels et al., 2001, 2004; Forman et al., 2017). It is also important to note that while dietary restraint–i.e., cognitive efforts to restrict food intake in order to control body weight (Polivy & Herman, 1985)– is often conceptualized as maladaptive for individuals with EDs, in the context of obesity, a moderate degree of dietary restraint may be adaptive in order to facilitate weight loss and improve physical health (Schaumberg, Anderson, Anderson, Reilly, & Gorrell, 2016). Given that both restraint and binge eating have been implicated as cognitive and behavioral influences on eating and weight control behaviors across a range of samples, it is important to determine affective predictors of binge eating and restraint among individuals with obesity. Such data may inform treatment approaches that can concurrently target binge eating and maximize health promoting behaviors.

Binge Eating

While obesity does not invariably co-occur with binge eating, individuals with overweight or obesity are more likely than those within healthy ranges to report current and lifetime histories of binge eating (Duncan, Ziobrowski, & Nicol, 2017), and epidemiological data indicate that 10.7 to 24.8% of individuals with BMI≥30 report a lifetime history of binge eating behavior (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007). Theoretical and empirical work has consistently indicated that NA plays a role in the etiology and maintenance of binge eating behavior (e.g., Hawkins & Clement, 1984; Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Stice, 2001; Stice, 2002; Wonderlich, et al., 2008) and that individuals who experience binge eating episodes evidence a range of emotion regulation difficulties (Lavender et al., 2015). With respect to momentary affect, research across various samples has consistently demonstrated that momentary NA increases prior to and decreases following binge eating episodes (e.g., Berg et al., 2015; Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), suggesting binge eating functions to regulate or “escape” from aversive emotional states.

However, less is known regarding the influence of positive emotionality on eating behaviors. One study of undergraduates found that the induction of positive affect (PA) was associated with higher caloric intake compared to a neutral condition (Bongers, Jansen, Havermans, Roefs, & Nederkoorn, 2013), although another study found that lower PA was associated with higher intake after the induction of NA (Emery, King, & Levine, 2014). Some studies have also examined positive affect in relationship to binge eating. Of note, two samples have used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to examine PA surrounding binge eating episodes. EMA provides a particularly useful methodology to assess current psychological states and behaviors in naturalistic environments, which decreases methodological problems of retrospective recall biases and increases the ecological validity of findings (Stone and Shiffman, 2002). Furthermore, repeated measurements allow for the temporal sequencing of variables and assessment of variability in constructs (Smyth et al., 2001).Extant evidence has indicated that, in contrast to NA, PA decreased prior to and increased following binge episodes in samples of women with bulimia nervosa (BN) (Smyth et al., 2007) and anorexia nervosa (AN) (Engel et al., 2013).

Restraint

Theoretical and empirical research suggests that dietary restraint is a central feature of ED psychopathology (Fairburn, 2008; Polivy & Herman, 1985; Stice, 2001). Whereas dietary restriction refers to a behavioral phenomenon in which one consumes less calories relative to his/her energy requirements, dietary restraint refers to a cognitive phenomenon in which one focuses on attempting to restrict food intake with the intent to influence weight or shape, regardless of the behavioral outcome (Lowe, Whitlow, & Bellwoar, 1991); thus, the present study will refer to dietary restraint as “restraint intention.” However, it is important to note that restraint is not a unidimensional construct, as it has been characterized as “rigid” (i.e., an extreme, all-or-nothing approach to limiting types and quantities of foods) or “flexible” (i.e., a graduated approach in which one attempts to limit quantities of certain foods but not eliminate entirely), and as “unhealthy” (i.e., involving extreme weight loss behavior and disordered eating, such as skipping meals) or “healthy” (i.e., lacking disordered eating or extreme behaviors; Gillen, Markey, & Markey, 2012; Westenhoefer et al., 2013).

Previous research suggests that 69.2% of women and 55.3% of men with overweight/obesity diet to control weight (Yaemsiri et al., 2011), and a recent study demonstrated increasing rates of dieting and fasting behaviors among individuals with obesity (Da Luz et al., 2017). Thus, restraint is particularly relevant for individuals with obesity or overweight, and successful restriction of intake and weight loss has significant health benefits (Garvey et al., 2012; Rueda-Clausen et al., 2015) even at a modest degree of weight loss (Wing et al., 2011). While some evidence supports restraint as a precursor to negative outcomes such as binge eating (Fairburn, 2008; Stice, 2001) and weight gain (Drapeau et al., 2003; Mann et al., 2007; Stice et al., 1999), other studies have not replicated these findings, as many individuals who attempt to restrict intake have been successful in losing and maintaining weight without engaging in disordered eating (Catenacci et al., 2014; Klem, Wing, McGuire, Seagle, & Hill, 1997; Phlelan et al., 2009; Wing & Phelan, 2005). In addition, some results have indicated that adherence to weight maintenance or weight loss diets was associated with a lower risk of weight gain, bulimic symptoms, and obesity (Presnell & Stice, 2003; Stice, Presnell, Groesz, & Shaw, 2005). Taken together, restraint does not appear to universally predict ED psychopathology or weight gain, and appears to have both unhealthy and healthy effects (Schaumberg et al., 2016).

A recent self-regulation model of restraint may help clarify somewhat disparate findings regarding relationships between restraint and health outcomes (Schaumberg et al., 2016). According to this model, restraint promotes healthy weight management via adaptive self-regulation processes, including self-monitoring (i.e., attending to one’s behavior), self-evaluation (i.e., comparing actual behaviors to ideal behaviors), and self-reinforcement (i.e., results of self-evaluations provide positive or negative self-reinforcement of relevant behaviors; Schaumberg et al., 2016). Thus, a failure in self-regulation processes (e.g., unrealistic goals, inconsistent monitoring, or a depletion in self-regulatory resources due to competing demands) can decrease the likelihood of engaging in adaptive forms of restraint, and instead lead to disinhibited eating and weight gain. This conceptualization is also somewhat consistent with a recent resource depletion account of binge eating, which suggests that both affect regulation and dietary restraint require cognitive resources, which, in turn depletes self-control and may lead to binge eating (Loth, Goldschmidt, Wonderlich, Lavender, Neumark-Sztainer, & Vohs, 2016).

However, thus far little is known regarding the influence of affect on restraint. While previous research has found that restraint predicted the onset of depression (Stice, Hayward, Cameron, Killen, & Taylor, 2000), it is also possible that depletion in self-regulatory resources (such as when one devotes resources to regulate affect) may lead to a decreased capacity to successfully maintain dietary restraint (Schaumberg et al., 2016). EMA studies of individuals with obesity/overweight found that dieting temptations and lapses were associated with greater negative mood states (Carels et al., 2001., 2004) and between-person differences in negative affect (Forman et al., 2017). Thus, high levels of NA may interfere with adaptive self-regulatory processes, and in turn lead to decreased dietary restraint and higher levels of binge eating. Conversely, PA may enhance self-regulatory processes and thereby result in increased restraint and decreased binge eating.

The present study

Taken together, restraint and binge eating are cognitive and behavioral processes that are of central importance to affect regulation and self-regulatory processes among individuals with obesity. However, to date, research has not examined differential associations between state and trait levels of NA and PA in relationship to binge eating and restraint among individuals with obesity. Examining trait-level affect helps to determine relevant individual differences in emotional dispositions that may be associated with eating behaviors and cognitions— for example, do individuals with obesity who are generally higher in negative affectivity (compared to the average level of negative affectivity in an obese sample) endorse more frequent binge eating and lower levels of cognitive restraint? Investigating trait-level affect may also help identify which individuals with obesity are most prone to engage in binge eating or have difficulties maintaining dietary restraint. Alternatively, examining state-level processes determines within-person variability and temporal antecedents of binge eating and restraint at a given time point. For example, at moments of relatively elevated negative affect (compared to an individuals’ average level of negative affect), is an individual more likely to engage in subsequent binge eating and/or experience reduced intention to adhere to dietary goals?

Therefore, the present study sought to clarify these relationships to determine how affective disturbances may lead to cognitive and behavioral self-regulation problems in obesity. Both trait- and state-level relationships between affect and eating-related cognitions and behaviors can inform obesity interventions by identifying which individuals may benefit most from emotion-based interventions, as well as when particular skills could be most helpful to reduce binge eating and maintain restraint. Based on previous research, we first evaluated a trait model, in which we expected individuals higher in overall negative affectivity (i.e., measured by trait-level variables) would report a higher number of total binge eating episodes (i.e., aggregated over the course of EMA) and lower levels of overall dietary restraint intention (i.e., averaged over the course of EMA) assessed using EMA over a two-week time period. Conversely, we predicted that individuals higher in overall positive affectivity would report a lower number of total binge eating episodes and higher levels of overall restraint intention as measured using EMA over two weeks. Second, we examined two momentary models in which we expected that (1) higher momentary NA (i.e., measured at a single time point via EMA) would be related to an increased likelihood of subsequent binge episodes (i.e., measured at the next EMA rating), whereas lower momentary PA would be related to a lower likelihood of subsequent binge episodes; and (2) higher momentary NA would be related to lower levels of subsequent restraint intention, whereas higher momentary PA would be related to higher levels of subsequent restraint intention. While several studies have previously published data from the present sample (e.g., Berg et al, 2015; Goldschmidt et al., 2014), thus far no study has examined trait- and state-level differences in affective valence in relationship to binge eating and restraint intention in this dataset.

Method

Participants

Participants included fifty men and women with obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30) who were recruited through advertisements and flyers in the Midwestern U.S. Exclusion criteria and study protocols have been previously described (Berg et al., 2014). Of note, exclusion criteria included concurrent treatment of obesity, and current or past diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. This study was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board.

When participants entered the study, they completed several in-person assessments, self-report surveys, and anthropometric measures. Participants then completed a two-week EMA protocol, in which they were instructed to complete EMA ratings on a handheld computer prior to and following each eating episode (i.e., any time they consumed food). The assessments prior to eating are referred to as pre-eating episode recordings and the assessments following eating are referred to as post-eating episode recordings. Participants also provided reports in response to six semi-random prompts occurring every 2–3 hours between 8:00am and 10:00pm, in which participants were given the opportunity to record recent eating episodes that they had not previously recorded. During the two-week protocol, one in-person visit was scheduled for each participant, during which data from the handheld computers were uploaded and participants were provided feedback regarding their compliance rates. Participants received $150 for their participation and were given a $50 bonus for completing at least 90% of EMA reports within 45 minutes of the computer signal.

Measures

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996)

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report measure that was used to assess depressive symptoms, reflecting the intensity of negative affective experiences. The Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .87.

EMA Affect

When recording a behavior and also in response to a signal, participants completed the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson & Clark, 1988) measuring negative affect and positive affect. Thirteen items were used to assess positive affect (i.e., happy, alert, proud, cheerful, enthusiastic, confident, concentrating, energetic, calm, strong, determined, attentive, and relaxed) and 11 items were used to assess negative affect (i.e., afraid, lonely, irritable, ashamed, disgusted, nervous, dissatisfied with self, jittery, sad, distressed, and angry with self). Respondents indicated on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) how much they felt each affective state at that moment. Items were summed to create a total negative affect score and a total positive affect score. The alphas for positive and negative affect were .92 and .91, respectively.

EMA Binge Eating and Restraint Intention

We defined binge eating as eating episodes in which participants reported both overeating and a loss of control. At post-eating episode recordings, overeating was measured with one item (i.e., “To what extent do you feel that you overate.”) and loss of control was measured with one item (i.e., “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel a sense of loss of control?). Participants responded to each item on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Episodes were coded as binge eating episodes when participants chose 3 or higher for both the overeating and loss of control items. Previous research has found moderate concordance (Spearman’s Rho=.57) between binge episodes measured via EMA and a structured clinical interview in this sample (Wonderlich et al., 2015). Restraint intention was measured with one item that participants responded to at pre-eating episode recordings (i.e., “I will eat less to lose weight or avoid gaining weight”). Participants responded to the item on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Previous research has found that this item corresponds to standard measures of dietary restraint (i.e., restraint subscales of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire and the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire; Mason et al., 2017a, 2017b).

Statistical Analyses

State- and Trait-Level Affect

Momentary (state) levels of affect were assessed by individual PANAS EMA PA and NA ratings. Trait-level positive affectivity was assessed by the mean of all PANAS PA ratings during the EMA protocol. A latent variable was calculated for trait-level NA affectivity, which was comprised of BDI total scores, aggregated EMA NA (i.e., mean of all PANAS NA ratings during the EMA protocol), and EMA affect lability, which was measured by the Mean Square Successive Difference (MSSD). The MSSD was calculated as the squared difference in EMA NA ratings across successive time points in relation to the distance between the measured time points, and therefore represents an individual’s average variability in affect over time (Witte, Fitzpatrick, Joiner, & Smith, 2005; Woyshville, Lackamp, Eisengart, & Gilliland, 1999). To appropriately identify the NA latent variable, at least three indicators were included and the factor loading of one of the indicators was fixed to 1. A latent variable was not created for PA due to lack of multiple measures. The following indices were used as guidelines in evaluating model fit: comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ .95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .06, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Given a relatively small sample size, bootstrapping with 5000 bootstrap samples was used. Significance testing was conducted using 95% bias-corrected (BC) confidence intervals (CIs) generated from 5,000 bootstrap samples. If the confidence interval did not include 0, it was considered significant.

State- and Trait-Level Restraint Intention and Binge Eating

Momentary levels of restraint intention were assessed by individual EMA ratings of restraint intention, while trait-level restraint intention was calculated by the mean of all restraint intention ratings during the EMA protocol. Momentary binge-episodes were assessed by individual EMA occurrences; overall binge eating was assessed by the total number of binge-eating episodes reported during the EMA protocol.

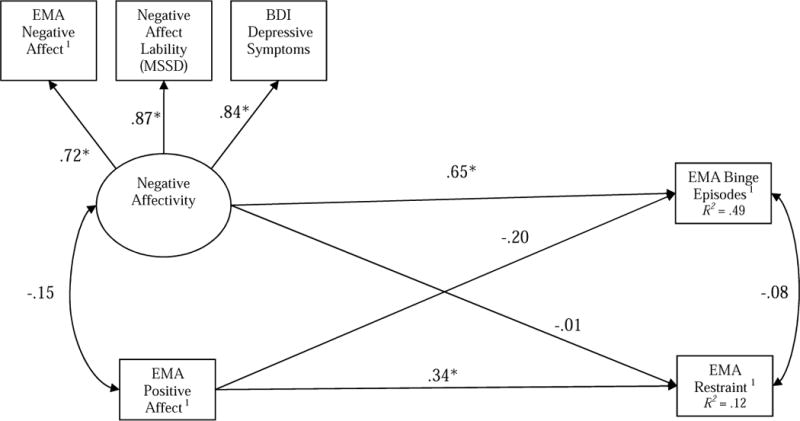

Structural equation modeling (SEM) with Mplus 7.31(Muthén & Muthén, 2015) was used to analyze the hypothesized trait model of trait-level negative and positive affectivity predicting overall levels of binge eating and restraint intention (Figure 1). Missing data were handled through full information maximum likelihood (Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

Figure 1.

Model of associations between trait negative affectivity and positive affectivity in relation to binge eating and dietary restraint. EMA=Ecological Momentary Assessment; MSSD=Mean Square Successive Difference. 1EMA variables were aggregated within persons.

A general estimating equation (GEE) using a binary logistic function (appropriate for a dichotomous outcome) was used to examine the state models of binge eating and a GEE using a gamma function (appropriate for skewed continuous data) was used to examine the state model of restraint intention. Time-lagged negative affect and positive affect were person mean centered and entered simultaneous in the models for binge eating and restraint intention. The aggregated means for positive affect and negative affect were also included in the model to account for between-subject variance. This variable was grand mean centered.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Most participants were women (n = 42; 84%) and White (n = 38; 76%). The mean BMI was 40.3 kg/m2 (SD = 8.5). Twelve participants had a lifetime diagnosis of BED (5 subthreshold and 7 full threshold) based on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR; of these 12 participants, 9 also had a current diagnosis of BED (4 subthreshold and 5 full threshold). Of the 50 participants who completed baseline assessments, 92% completed the EMA protocol, with the remaining 8% terminating early due to personal circumstances or perceived burden of completing EMA recordings. All participants were included in study analyses. There were 1,709 pre-eating episode recordings and 1,715 post-eating episode recordings; 23.2% of eating episodes were rated as binge episodes. The mean number of binge eating episodes reported was 7.18 (SD = 7.80; Range = 0 – 29). The mean restraint intention over the course of EMA was 3.10 (SD = 1.02; Range = 1 – 5).

Trait Model of Affect, Binge Eating, and Restraint Intention

The hypothesized trait model of binge eating and restraint intention demonstrated adequate model fit, |2 (6) = 8.20, p = .22, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .09, and SRMR = .03. The model (Figure 1) indicated that individuals higher in NA affectivity reported more binge eating episodes, Estimate = .49, SE = .18, 95% BC CI [.21, .86]. PA affectivity was unrelated to binge eating, Estimate = −.18, SE = .12, 95% BC CI [-.43, .06]. However, individuals who reported higher PA reported more restraint intention, Estimate = .04, SE = .02, 95% BC CI [.01, .07]. In contrast, NA was unrelated to restraint intention, Estimate = −.001, SE = .02, 95% BC CI [−.03, .03]. Affect variables explained 49% of the variance in binge eating and 12% of the variance in restraint intention.

State Models of Affect, Binge Eating, and Restraint Intention

Momentary NA was associated with a greater likelihood of binge eating episodes, Estimate = .05, SE = .02, p = .01. This association suggests that when individuals experienced heightened momentary NA, they were subsequently more likely to report a binge eating episode, as previously reported by Berg et al. (2015). However, the relationship between momentary PA and likelihood of binge eating episodes was not statistically significant, Estimate = .03, SE = .01, p = .07.

Momentary NA was also associated with lower restraint intention in the moment, Estimate = −.01, SE = .003, p = .02. This association demonstrates that when individuals experienced greater momentary NA than average, they subsequently reported less restraint intention. Momentary PA was unrelated to restraint intention, Estimate = .001, SE = .001, p = .30.

Discussion

The present study examined relationships between trait and state levels of affect, binge eating, and restraint intention among individuals with obesity. In partial support of the hypothesized trait model, higher trait NA was related to a higher frequency of binge eating episodes, yet trait NA was unrelated to participants’ overall level of restraint intention. Conversely, higher trait PA was related to a higher overall level of restraint intention, but was unrelated to binge eating. Also partially consistent with the hypothesized state models, higher momentary NA was predictive of a greater likelihood of subsequent binge eating episodes and lower levels of subsequent restraint intention. However, momentary PA was unrelated to subsequent binge eating or restraint intention. Taken together, these findings demonstrate important distinctions between the valence (i.e., positive versus negative) and stability (i.e., state versus trait) of affect in relationship to binge eating and restraint intention among individuals with obesity.

First, results suggested that state and trait levels of NA are most relevant in predicting state- and trait-level measurements of binge eating, respectively. These findings converge with an extensive body of research demonstrating relationships between overall NA and binge eating (e.g., Stice, 2001), as well as momentary NA precipitating binge eating episodes in this dataset (Berg et al., 2015) and others (Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011). Thus, results lend further support for the affect regulatory function of binge eating among individuals with obesity, and suggest that interventions that target binge eating should not only aim to improve overall negative mood states but also provide means of coping with momentary increases in NA (e.g., distress tolerance skills). The present findings are also interesting in light of a previous cluster analysis that found individuals with overweight and obesity could be classified into two subtypes that were high and low in NA (Jansen, Havermans, Nederkoorn, & Roefs, 2008) and which differed in response to negative mood inductions and food exposures. That is, the overweight high NA group consumed significantly more kilocalories after a negative mood induction compared to the overweight low NA group (Jansen, Vanreyten, van Balveren, Roefs, Nederkoorn, & Havermans, 2008). Therefore, the present findings appear to be particularly relevant for a subgroup of individuals with obesity who are high in NA and may be at heightened risk for binge eating.

Second, differential findings emerged with respect to state and trait levels of affect in relationship to restraint intention. Trait positive, not negative, affectivity was related to higher levels of restraint intention, although the directionality of this relationship cannot be determined. One possibility is that consistently higher levels of PA facilitate self-efficacy in overcoming perceived challenges of resisting high caloric foods, which is consistent with research demonstrating relationships between self-efficacy and weight loss maintenance (Elfhag et al., 2005). This finding is also consistent with prior research suggesting PA engenders goal-oriented actions and success in multiple life domains (Lyubormirsky, King, & Diener, 2005), including positive physical health outcomes (Pressman & Cohen, 2005). Notably, advances in affective neuroscience have also informed the recent development of Positive Affect Treatment (PAT; Craske, Meuret, Ritz, Treanor, & Dour, 2016), which suggests that exclusively targeting positive valence systems (i.e., anticipation, consumption, reward) leads to global symptom improvement among individuals with depression and anxiety. While evidence supporting this treatment is yet preliminary, it may be useful for future studies to examine these intervention techniques in obese samples.

However, the promotion of PA may not necessarily produce restraint or weight loss, and it may be most effective to promote PA via interventions that target mechanisms that have been linked to successful weight control among individuals with obesity/overweight. Self-efficacy, motivation, self-regulation skills, flexible restraint, and positive body image have been shown to mediate outcomes of behavioral interventions in overweight/obese populations (Teixeira et al., 2015); thus, these may represent important intervention targets that indirectly promote PA via increased self-esteem and self-efficacy, and thereby facilitate successful behavioral change. Additionally, given the established relationships between physical activity and positive affect (Li, Shonkoff, & Dunton, 2015) and the significance of exercise in behavioral weight management (Johns, Hartmann-Boyce, Jebb, & Aveyard, 2016), the promotion of exercise in conjunction with other weight management strategies is another mechanism by which positive affect may indirectly influence adaptive restraint among those with obesity. Furthermore, while findings related to binge eating only apply to a subgroup of individuals with obesity who experience such behavior, the promotion of healthy forms of restraint is relevant for a broader range of individuals within this population who are attempting to lose or prevent gaining weight.

At the momentary level, however, state levels of NA, not PA, were most relevant in predicting subsequent decreased restraint intention. Thus, temporary elevations in NA appear to interfere with individuals’ cognitive efforts to restrict food intake, which may be related to depletion of self-regulation resources (Loth et al., 2016). This finding is somewhat contrary to a previous EMA study of adults (for whom the mean BMI was in the overweight/obese range) that found lower levels of PA, not NA, after an experience of weight stigma were related to decreased motivation to diet, but only among women and those with higher internalized weight bias and previous stigma experiences (Vartanian, Pinkus, & Smyth, 2016). Conversely, it is also possible that higher state levels of restraint lead to higher PA, which would useful to examine in future studies.

These results are also notable in light of research demonstrating several ways in which emotional experiences influence eating behavior broadly, even in the absence of eating psychopathology (for a review see Macht, 2008). While it has been suggested that both positive and negative emotions impair cognitive control over eating, the present results suggest that transient negative, not positive affect may be particularly detrimental to cognitive control measured in the form of dietary restraint. Conversely, overall positive affect could have an enhancing effect on restraint in obesity. In addition, the finding that negative but not positive affectivity predicted binge eating likely reflects greater emotional eating tendencies among some individuals with obesity, which is consistent with a research demonstrating emotional eating is a common phenomenon in this population (e.g., Ganley, 1989).

Future Directions

While these findings lend some support to the self-regulation model of restraint (Schaumberg et al., 2015), it would be beneficial to identify antecedents and consequences of maladaptive and adaptive forms of restraint at the momentary level. Doing so could clarify the specificity of relationships between affect and restraint, and elucidate under what circumstances dietary restraint translates into behavioral restriction. It is also worth noting that affect variables explained 49% of the variance in binge eating but only 12% of the variance in restraint in the trait model. Therefore, further research is needed to examine other environmental, social, and neurocognitive factors that may affect these relationships, particularly with respect to restraint. For example, obesity is broadly associated with inhibitory control deficits (Lavagnino et al., 2016), which may underlie impairments in cognitive control over eating (i.e., restraint) and emotion regulation difficulties. It would be useful for future studies to assess if and how state and trait levels of inhibitory control may moderate relationship between affect, restraint, and binge eating in daily life among individuals with obesity. A wealth of research has also demonstrated that environmental and social factors contribute to obesity (e.g., Hill & Peters, 1998; Slack, Myers, Martin, & Heymsfield, 2014), and that individuals with obesity are more responsive to food cues (e.g., Van den Akker, Stewart, Antoniou, Palmberg, & Jansen, 2014). As such, it would be useful to examine the influence of such factors on eating at the momentary level; for instance, the presence of and attendance to palatable food cues could in part explain the extent to which individuals maintain cognitive control over eating (i.e., restraint) and their relative likelihood of binge eating.

Limitations

The present study is not without limitations. While the study has strength in the use of EMA, these assessments nevertheless were subject to limitations of self-report. With respect to binge episodes, it was not possible to validate the caloric quantity of binge episodes through objective measurement. We also cannot determine whether participants’ loss of control over eating would have been rated similarly to those of trained interviewers. As previously noted, prior research found moderate concordance between binge eating frequency measured via structured clinical interview and EMA, and that there was a pattern for somewhat more frequent binge episodes reported via EMA than interview (Wonderlich et al., 2015); thus, while there is some convergence between these assessment strategies, there are also meaningful differences that may have influenced the present results. It is possible that participants without BED (which represented the majority of the sample) overreported EMA binge episodes, which could have resulted in a lack of concordance between interview and EMA binge episodes. Conversely, earlier research has also suggested that retrospectively reported binge episodes during clinical interviews may underestimate binge eating in obese samples (Greeno, Wing, & Shiffman, 2000; Le Grange, Gorin, Catley, & Stone, 2001).

Additionally, momentary restraint intention was assessed using a single item, and it is unclear the extent to which participants were attempting to engage in adaptive or maladaptive forms of restraint. Given that this study did not assess current dieting, it would also be important to examine the role of the active pursuit of weight loss in future study. With respect to the trait model, we were also only able to utilize one indicator of PA, and it would be useful for future to employ multiple measures of trait PA. Furthermore, because trait-level affect was partially (NA) or fully (PA) comprised of momentary ratings, there is some degree of overlap in these constructs. While NA and PA items have been shown to reflect higher-order affect dimensions, it is also unclear whether specific facets of NA or PA evidenced different relationships with binge eating and restraint intention, which would useful to explore in future studies. Another limitation is that the sample consisted of predominantly Caucasian females, which limits generalizability to males and other ethnicities/races. In addition, given that a small proportion of individuals met diagnostic criteria for BED, there was not sufficient statistical power to evaluate if and how observed relationships may differ between individuals with and without co-occurring BED. However, given that the present study relied on DSM-IV criteria, it is likely that a larger proportion of individuals met DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) criteria for BED given that the revised criteria use lower binge eating frequency and duration thresholds.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations of the present study, results yielded novel and clinically useful information. Consistent with previous literature, NA is a salient predisposing factor in binge eating, which supports the use of emotion regulation intervention strategies to target binge eating among individuals with obesity who present with such behavior. With respect to restraint, it may be useful to further explore methods to specifically promote positive mood and identify other relevant factors that promote adaptive restraint at the momentary level. Additionally, strategies to address momentary NA are also important to reduce the likelihood individuals will abandon dietary goals when experiencing temporary emotional distress. In addition, future research is needed to elucidate affective and behavioral correlates and sequelae of adaptive and maladaptive forms of restraint in the context of obesity. Doing so may serve to more precisely address health promoting behaviors among individuals with obesity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant number P30DK 50456) and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number T32 MH082761).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brow GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) San Antonio, TX: Psychology Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Crosby RD, Cao L, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB. Negative affect prior to and following overeating-only, loss of control eating-only, and binge eating episodes in obese adults. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2015;48(6):641–653. doi: 10.1002/eat.22401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Cao L, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA. Relationship between daily affect and overeating-only, loss of control eating-only, and binge eating episodes in obese adults. Psychiatry Research. 2014;215(1):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers P, Jansen A, Havermans R, Roefs A, Nederkoorn C. Happy eating. The underestimated role of overeating in a positive mood. Appetite. 2013;67:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catenacci VA, Phelan S, Thomas JG, Hill J, Wing RR, Wyatt H. Dietary habits and weight maintenance success in high versus low exercisers in the national weight control registry. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2014;11(8):1540–1548. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Meuret AE, Ritz T, Treanor M, Dour HJ. Treatment for anhedonia: A neuroscience driven approach. Depression and Anxiety. 2016;33(10):927–938. doi: 10.1002/da.22490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Luz FQ, Sainsbury A, Mannan H, Touyz S, Mitchison D, Hay P. Prevalence of obesity and comorbid eating disorder behaviors in South Australia from 1995 to 2015. International Journal of Obesity. 2017;41(7):1148–1153. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AE, Ziobrowski HN, Nicol G. The Prevalence of Past 12‐Month and Lifetime DSM‐IV Eating Disorders by BMI Category in US Men and Women. European Eating Disorders Review. 2017;25(3):165–171. doi: 10.1002/erv.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau V, Provencher V, Lemieux S, Despres J, Bouchard C, Tremblay A. Do 6-y changes in eating behaviors predict changes in body weight? results from the Quebec family study. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27(7):808–814. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfhag K, Rossner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obesity Reviews. 2005;6(1):67–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RL, King KM, Levine MD. The moderating role of negative urgency on the associations between affect, dietary restraint, and calorie intake: An experimental study. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;59:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel Scott G, Wonderlich Stephen A, Crosby Ross D, Mitchell James E, Crow Scott, Peterson Carol B, Le Grange Daniel, Simonich Heather K, Cao Li, Lavender Jason M, et al. The role of affect in the maintenance of anorexia nervosa: Evidence from a naturalistic assessment of momentary behaviors and emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(3):709. doi: 10.1037/a0034010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Enhanced cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders (“CBT-E”): An overview. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. 2008:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ganley RM. Emotion and eating in obesity: A review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1989;8(3):343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, Gadde KM, Allison DB, Peterson CA, Bowden CH. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;95(2):297–308. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.024927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen MM, Markey CN, Markey PM. An examination of dieting behaviors among adults: Links with depression. Eating Behaviors. 2012;13(2):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Crosby RD, Cao L, Engel SG, Durkin N, Beach HM, Peterson CB. Ecological momentary assessment of eating episodes in obese adults. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76(9):747. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Grange D, Mitchell JE. Momentary affect surrounding loss of control and overeating in obese adults with and without binge eating disorder. Obesity. 2012;20(6):1206–1211. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeno CG, Wing RR, Shiffman S. Binge antecedents in obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(1):95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(4):660. doi: 10.1037/a0023660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins R, Clement PF. Binge eating: Measurement problems and a conceptual model. The Binge-Purge Syndrome. 1984:229–253. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A, De Zwaan M, Braehler E. How frequent are eating disturbances in the population? norms of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire. PloS One. 2012;7(1):e29125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Peters JC. Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science. 1998;280(5368):1371–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L, Bentler M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen A, Havermans R, Nederkoorn C, Roefs A. Jolly fat or sad fat?: Subtyping non-eating disordered overweight and obesity along an affect dimension. Appetite. 2008;51(3):635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen A, Vanreyten A, van Balveren T, Roefs A, Nederkoorn C, Havermans R. Negative affect and cue-induced overeating in non-eating disordered obesity. Appetite. 2008;51(3):556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns DJ, Hartmann-Boyce J, Jebb SA, Aveyard P, Group, B. W. M. R Diet or exercise interventions vs combined behavioral weight management programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2014;114(10):1557–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, Seagle HM, Hill JO. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1997;66(2):239–246. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leehr EJ, Krohmer K, Schag K, Dresler T, Zipfel S, Giel KE. Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity-a systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015;49:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Gorin A, Catley D, Stone AA. Does momentary assessment detect binge eating in overweight women that is denied at interview? European Eating Disorders Review. 2001;9(5):309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Biglan A, Zeiss AM. Behavioral treatment of depression. The Behavioral Management of Anxiety, Depression and Pain. 1976:91–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Shonkoff ET, Dunton GF. The acute relationships between affect, physical feeling states, and physical activity in daily life: a review of current evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:1975. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loth KA, Goldschmidt AB, Wonderlich SA, Lavender JM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Vohs KD. Could the resource depletion model of self-control help the field to better understand momentary processes that lead to binge eating? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2016;49(11):998–1001. doi: 10.1002/eat.22641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe MR, Whitlow JW, Bellwoar V. Eating regulation: The role of restraint, dieting, and weight. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1991;10(4):461–471. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? American Psychological Association; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew A, Samuels B, Chatman J. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. American Psychologist. 2007;62(3):220. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason TB, Pacanowski CR, Lavender JM, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Peterson CB. Evaluating the ecological validity of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire among obese adults using ecological momentary assessment. Assessment. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1073191117719508. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason TB, Smith KE, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Peterson CB. Does the eating disorder examination questionnaire global subscale adequately predict eating disorder psychopathology in the daily life of obese adults? Eating and Weight Disorders. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s40519-017-0410-0. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Haines J, Story M, Eisenberg ME. Why does dieting predict weight gain in adolescents? findings from project EAT-II: A 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107(3):448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan S, Liu T, Gorin A, Lowe M, Hogan J, Fava J, Wing RR. What distinguishes weight-loss maintainers from the treatment-seeking obese? Analysis of environmental, behavioral, and psychosocial variables in diverse populations. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;38(2):94–104. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Herman CP. Dieting and binging: A causal analysis. American Psychologist. 1985;40(2):193. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.40.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presnell K, Stice E. An experimental test of the effect of weight-loss dieting on bulimic pathology: Tipping the scales in a different direction. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2003;112(1):166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(6):925. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaumberg K, Anderson D, Anderson L, Reilly E, Gorrell S. Dietary restraint: What’s the harm? A review of the relationship between dietary restraint, weight trajectory and the development of eating pathology. Clinical Obesity. 2016 doi: 10.1111/cob.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist. 2005;60(5):410. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack T, Myers CA, Martin CK, Heymsfield SB. The geographic concentration of US adult obesity prevalence and associated social, economic, and environmental factors. Obesity. 2014;22(3):868–874. doi: 10.1002/oby.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J, Wonderlich S, Crosby R, Miltenberger R, Mitchell J, Rorty M. The use of ecological momentary assessment approaches in eating disorder research. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30(1):83–95. doi: 10.1002/eat.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2007;75(4):629. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(1):124. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Hayward C, Taylor CB. Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(6):967. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Hayward C, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Taylor CB. Body-image and eating disturbances predict onset of depression among female adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(3):438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Presnell K, Groesz L, Shaw H. Effects of a weight maintenance diet on bulimic symptoms: An experimental test of the dietary restraint theory. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2005;24(4):402. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S. Capturing momentary, self-report data: A proposal for reporting guidelines. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24(3):236–243. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Marques MM, Rutter H, Oppert JM, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Brug J. Successful behavior change in obesity interventions in adults: a systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Medicine. 2015;13(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0323-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Akker K, Stewart K, Antoniou EE, Palmberg A, Jansen A. Food cue reactivity, obesity, and impulsivity: Are they associated? Current Addiction Reports. 2014;1(4):301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian LR, Pinkus RT, Smyth JM. Experiences of weight stigma in everyday life. Stigma and Health 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenhoefer J, Engel D, Holst C, Lorenz J, Peacock M, Stubbs J, Raats M. Cognitive and weight-related correlates of flexible and rigid restrained eating behaviour. Eating Behaviors. 2013;14(1):69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, Safford M, Knowler WC, Bertoni AG, Look AHEAD Research Group Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1481–1486. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte TK, Fitzpatrick KK, Joiner TE, Schmidt NB. Variability in suicidal ideation: a better predictor of suicide attempts than intensity or duration of ideation? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;88:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woyshville MJ, Lackamp JM, Eisengart JA, Gilliland JA. On the meaning and measurement of affective instability: clues from chaos theory. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich JA, Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Crosby RD. Examining convergence of retrospective and ecological momentary assessment measures of negative affect and eating disorder behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2015;48(3):305–311. doi: 10.1002/eat.22352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Peterson CB, Robinson MD, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Strauman TJ. Examining the conceptual model of integrative cognitive‐ affective therapy for BN: Two assessment studies. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(8):748–754. doi: 10.1002/eat.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski SZ. Binge eating disorder and obesity in 2003: Could treating an eating disorder have a positive effect on the obesity epidemic? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;34(S1):S117–S120. doi: 10.1002/eat.10211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaemsiri S, Slining MM, Agarwal SK. Perceived weight status, overweight diagnosis, and weight control among US adults: the NHANES 2003-2008 Study. International Journal of Obesity. 2011;35(8):1063. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]