Abstract

There is growing recognition of benefits of sophisticated information technology (IT) in nursing homes. In this research, we explore strategies nurse assistants use to communicate pressure ulcer prevention practices in nursing homes with variable IT sophistication measures. Primary qualitative data was collected during focus groups with nursing assistants in 16 nursing homes located across Missouri. Nursing assistants (n=213) participated in 31 focus groups. Three major themes referencing communication strategies for pressure ulcer prevention were identified, including Passing on Information, Keeping Track of Needs and Information Access. Nurse assistants use a variety of strategies to prioritize care and strategies are different based on IT sophistication level. Nursing assistant work is an important part of patient care. However, little information about their work is included in communication, leaving patient records incomplete. Nursing assistant’s communication is becoming increasingly important in the care of the millions of chronically ill elders in nursing homes.

Keywords: Nursing Home, Information Technology, Patient Safety, Communication, Focus Groups

Globally, there are increasing priorities placed on Long-Term and Post-Acute Care settings to adopt and use health information technology (IT; International Federation on Aging [IFA], 2012). International federations have stressed that as life expectancy continues to rise, technology must be incorporated as a tool to maximize service delivery and support healthy ageing across the spectrum of care (IFA, 2012). For over a decade, national priorities in the U.S. have focused on how IT adoption will improve care for 1.5 million residents’ living in long-term care environments (Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety, 2003). The focus in this paper is communication strategies in nursing homes (NH). Oftentimes these communication strategies involve IT and sometimes not. A NH is for people who need healthcare services that don’t need to be in a hospital, but can’t be cared for at home (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/nursinghomes.html). IT in this paper refers to systems that replace paper medical records with electronic health records.

NH IT adoption is rarely assessed to identify systems best suited to improve residents’ outcomes. The purpose of this study is to use qualitative methods to describe how communication between NH staff about pressure ulcer prevention practices varies with differing levels of IT Sophistication in resident care, clinical support and administrative activities. The specific aim and research questions for this study were:

Purpose

Explore strategies Nurse Asssistants (NA) use to communicate pressure ulcer prevention practices in NH ranging between high IT sophistication to low IT sophistication.

What types of communication strategies are implemented for NAs to use for residents at risk of developing pressure ulcers in NH ranging from high IT to low IT sophistication?

What strategies does NAs use to prioritize skin care options for residents at risk of developing pressure ulcers in NH ranging from high to low IT sophistication?

We define IT sophistication as the maturity and diversity of IT used to support resident care, clinical support, and administrative activities (Pare & Sicotte, 2001). The U.S. Centre for Technology and Aging identified seven technology domains that are a high priority for diffusion including systems that provide chronic disease management (IFA, 2012). These systems should provide enhanced clinical decision support, enhanced information exchange, and more information at the point of care (IFA, 2012). In this paper, we focus on communication strategies about pressure ulcer prevention used by Nursing Assistants (NAs) because they are often closest to the resident, assisting with personal care, and in the best position to make observations that could indicate change in condition (Castle, Engberg, Anderson, & Men, 2007). Therefore, IT systems should enhance the ability of NAs to communicate such information.

Pressure Ulcers in Nursing Homes

NH residents who develop pressure ulcers may be at significantly increased risk of morbidity and mortality (Sullivan & Schoelles, 2013). Pressure ulcer lesions caused by unrelieved pressure that typically occurs over bony prominences usually result in damage to overlying tissues (Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, 2012). The costs of caring for pressure ulcers include up to a 50% increase in nursing time and treatment costs per ulcer ranging from $10,000 to $86,000 with a median of $27,000 (Clarke et al., 2005). In addition to healthcare costs, pressure ulcers also adversely impact the quality of life of older adults by causing pain, sleep disturbances, social isolation and emotional problems (Ahn, Stechmiller, & Horgas, 2013; Gorecki et al., 2009). To lower the prevalence, incidence, and cost of pressure ulcers, we must identify at-risk residents earlier and then initiate evidence-based prevention strategies immediately and consistently. The action plans recommended for implementing such quality improvement initiatives include: (1) designing and maintaining evidence-based prevention and treatment strategies, and (2) building necessary IT infrastructure to support care delivery (Stevens & Staley, 2006). Specifically, IT systems may be able to improve the usage of evidence-based guidelines for pressure ulcer prevention, standardize care delivery, and offer improved administrative oversight to improve pressure ulcer outcomes in NHs.

IT Sophistication in Nursing Homes

IT sophistication is highly heterogeneous in NH settings, resulting in variable outcomes (Sittig & Singh, 2012). Growing international recognition of the benefits of IT sophistication in NH care has prompted research studies exploring the effect of IT on quality (IFA, 2012). For example, in Australia benefits were recognized in a study of nine residential aged care facilities after the implementation of an electronic health record (Wang, Yu, & Hailey, 2013; Zhang & Shen, 2012). Residential aged care staff benefitted from efficient documentation systems, smoother communication, and improved working environments. Several IT studies have originated in Australia examining the role of information exchange, documentation, and workflow in aged care facilities (Gaskin, Georgiou, Barton, & Westbrook, 2012; Qian et al., 2012; Munyisia, Yu, & Hailey, 2012). Norwegian researchers have explored IT with clinical decision support capabilities in 15 NH (Fossum, Alexander, Goransson, Ehnfors, & Ehrenberg, 2011; Fossum, Alexander, Ehnfors, & Ehrenberg, 2011). This quasi-experimental study examined the effect of clinical decision support on conducting nutritional and pressure ulcer risk assessments. Results indicate malnourishment decreased in intervention group residents; no other significant results were found.

IT sophistication in long term care nationally in the U.S. has received increasing attention since the Institute of Medicine’s Improving Quality of Long-Term Care (Wunderlich & Kohler, 2001). The report cited the importance of IT toward improvements in reliability, validity, and timeliness of resident care data used to measure quality. In the US, the most recent national assessment of NH IT was completed by the National Center of Health Statistics in 2004, with secondary analysis completed in 2009 (Resnick, Manard, Stone, & Alwan, 2009). In 2004, IT sophistication was increasing in NH. There are studies of the use of IT in NH in several states, including infection control practices in Utah, electronic health record implementation in Texas, and workarounds related to electronic medication administration systems in Missouri (Jones, Samore, Carter, & Rubin, 2012; Cherry, 2011; Vogelsmeier, Halbesleben, & Scott-Cawiezell, 2008).

The current study arose from parent studies evaluating NH IT sophistication in Missouri (Alexander & Wakefield, 2009; Alexander, Madsen, Herrick, & Russell, 2008; Alexander & Madsen, 2009; Alexander, Madsen, & Wakefield, 2010; Alexander, Pasupathy, Steege, Strecker, & Carley, 2014). In one of the parent studies, the author of this paper developed an IT sophistication measure and completed a statewide study of IT sophistication in all Missouri NH. In this preliminary work we estimated Functional IT Sophistication, Technological IT Sophistication, and Integration IT Sophistication. Functional IT Sophistication is a measure of the capability of an IT system. Technological IT Sophistication is a measure of the extent of use of different IT systems with various capabilities, like lab results reporting. Finally, Integration IT Sophistication reflects the degree of integration with internal and external IT systems used by a NH. In the parent studies, we explored relationships between IT sophistication and NH Quality Measures. Results indicated that there are significant correlations between increasing IT sophistication and NH quality measures, such as percentage of residents with Decline in Activities of Daily Living and Incontinence, among the participating Missouri NH (Alexander & Madsen, 2009).

The purpose of the current study was to conduct qualitative assessments in a sample of the same NH facilities, with a wide range of IT sophistication measures, to shed light onto why these correlations existed, and to generate additional research questions. Our focus was on communication strategies, because core functions of increasing IT sophistication with clinical information systems is improved communication and connectivity (Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety, 2003) . In this research, we focused on NAs. There is a dearth of understanding of the impact of IT sophistication on health care workers other than licensed nursing staff. We believe increasing IT sophistication improves communication between licensed nursing staff and NAs and this is the reason for the significant correlations between IT sophistication and quality measures. To achieve our aims, we provided a venue for NAs to discuss how IT influences communication in relation to pressure ulcer prevention practices. Pressure ulcers are a recognized quality measure with specific communication expectations, providing a clinical context for discussions with NAs about IT and communication.

Method

Study Population: Nursing Home Selection

Our sampling strategy had two stages. The first stage combined data from 9 subscales of an IT sophistication survey, collected from 185 facilities participating in the parent study (Alexander et al., 2010). Measures of IT sophistication, in each healthcare domain (resident care, clinical support, and administrative activities), and total IT sophistication were calculated in our initial assessments and found to be reliable and valid measures (Alexander, Steege, Pasupathy, & Strecker, in press). Each scale had a theoretical maximum of 100 (maximum=900). Second, a clustering procedure, using the Centroid method for finding distances between clusters, was used with total IT sophistication. The clustering procedure provided a method to select three groups of NH with HIGH, MEDIUM, and LOW total IT sophistication (see Table 1). Based on this methodology, we purposively recruited the 5 NH with the highest total IT sophistication, 6 NH with medium total IT sophistication, and 5 NH from the lowest total IT sophistication group.

Table 1.

Demographics of Participating NH with Total IT Sophistication by Domain by Healthcare Dimension

| Resident Care (Range 0-100) |

Clinical Support (Range 0-100) |

Administrative Activities (Range 0-100) |

Total ITS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| IT Sophistication Level | Location | Bed size | Ownership | Funct | Tech | Int | Funct | Tech | Int | Funct | Tech | Int | |

| High | Metro | 60-120 | Not-For-Profit | 91 | 62 | 100 | 81 | 65 | 83 | 50 | 46 | 80 | 661 |

| Urban | 60-120 | Not-For-Profit | 93 | 62 | 100 | 81 | 65 | 83 | 50 | 46 | 78 | 660 | |

| Urban | 60-120 | Not-For-Profit | 93 | 62 | 100 | 76 | 65 | 83 | 50 | 46 | 80 | 658 | |

| Rural | >120 | Not-For-Profit | 91 | 62 | 100 | 76 | 65 | 83 | 50 | 46 | 80 | 656 | |

| Urban | 60-120 | Not-For-Profit | 91 | 49 | 100 | 81 | 65 | 83 | 50 | 44 | 75 | 642 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Medium | Rural | 60-120 | For Profit | 16 | 13 | 1 | 16 | 23 | 2 | 20 | 38 | 41 | 174 |

| Metro | 60-120 | For Profit | 23 | 10 | 19 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 32 | 38 | 141 | |

| Urban | 60-120 | For Profit | 35 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 22 | 43 | 141 | |

| Metro | >120 | Not-For-Profit | 28 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 41 | 45 | 140 | |

| Urban | 60-120 | For Profit | 29 | 6 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 19 | 34 | 132 | |

| Metro | 60-120 | For Profit | 23 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 27 | 113 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Low | Rural | 60-120 | For Profit | 8 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 21 | 26 | 75 |

| Urban | 60-120 | For Profit | 9 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 22 | 68 | |

| Metro | 60-120 | Not-For-Profit | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 16 | 59 | |

| Metro | 60-120 | For Profit | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 17 | 49 | |

| Urban | >120 | For Profit | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 21 | 44 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Key | Funct: Functional IT sophistication | ||||||||||||

| Tech: Technological IT sophistication | |||||||||||||

| Int: Integration IT sophistication | |||||||||||||

The 16 participating NH were demographically and geographically diverse (Table 1). Six facilities were located in metropolitan areas, 7 urban and 3 rural. Thirteen were medium size between 60-120 beds. Nearly half were Not-For-Profit. IT sophistication was diverse. The HIGH IT group reported total IT sophistication scores ranging from 642-661. HIGH IT NH achieved a high level of Functional IT sophistication in resident care (>90) that was also highly integrated with other internal and external IT sources, such as nursing documentation and laboratory reporting. Total IT sophistication scores for MEDIUM NH ranged from 113-174. MEDIUM IT facilities have a higher degree of Functional IT sophistication in resident care and administrative support activities; compared to clinical support, which had no IT being used in at least 4 facilities. Finally, the LOW IT group had IT sophistication totals ranging from 44-75, because very low IT sophistication was found in all individual dimensions that comprise the total score.

Focus Group Recruitment

A convenience sample of NAs was recruited from each NH, because they play a major role in communication, and this communication contributes to early illness detection (Castle et al., 2007). NAs are, oftentimes, the eyes and ears of licensed nurses and should make deliberate and strategic efforts to share clinical observations and information with these professionals (Dellefield, Harrington, & Kelly, 2012). Our motivation for using focus groups was to discover how nurse assistants strategize and communicate about pressure ulcer preventions they use in work processes. Focus groups can provide a broad range of information about groups and processes used to conduct work. Our focus groups consisted of 6-10 voluntary participants. Focus groups were conducted on each shift, over a minimum of two days, in each of 16 nursing facilities. We recruited all available NAs willing to participate, in an attempt to garner a sample with diverse opinions and backgrounds. We collected information about job role held by CNA’s, educational level and length of employment to describe diversity across the 16 NH. We assessed training and experience levels because these characteristics are linked with NH IT outcomes, including acceptance and use of IT (Yu, Li, & Gagnon, 2009).

Focus Group Procedures

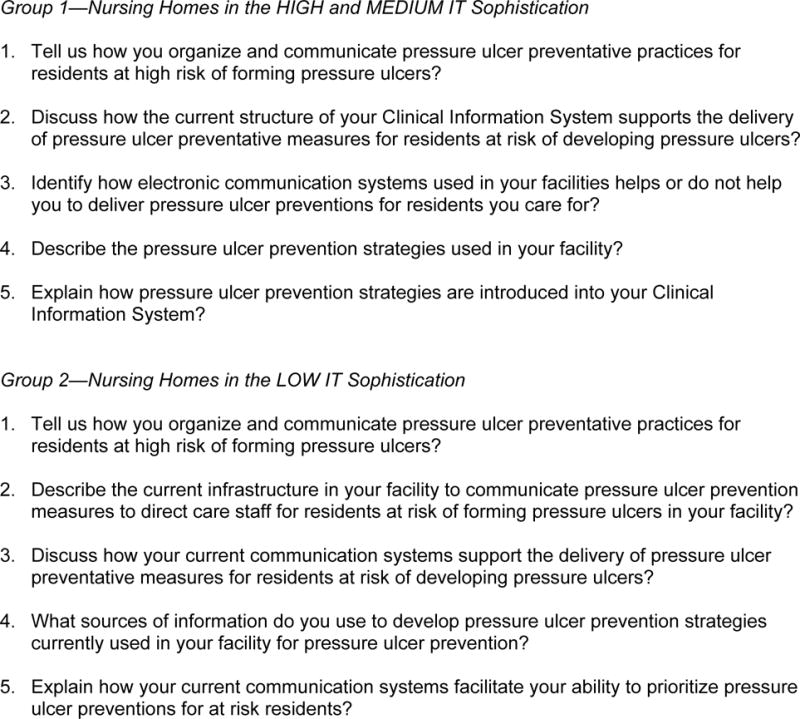

Focus groups began by describing study purpose and goals. A structured focus group guide was developed based on the level of IT sophistication for each facility since communication strategies will vary depending on IT sophistication levels (i.e. IT capabilities, extent of IT use, and IT integration levels (see Figure 1). For each facility, we collected qualitative data to evaluate how staff organized and communicated about pressure ulcer preventions. To maintain consistency across NH, questions on the guide were asked verbatim at each focus group for each type of nursing facility, high, medium, and low tech. Pause-and-probe methods were used to clarify meaning, until saturation of a topic was reached; that is, the point when information being shared became repetitive and no new ideas emerged (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber, 2010). All interviews were digitally recorded and later transcribed. To improve credibility, field notes were documented by a research assistant during interviews for later clarification. For example, field notes provided some further context about how staff responded to questions, including non-verbal reactions to questions, which are not evident on digital recordings. No personal identifying information was collected. The Institutional Review Board approved study procedures.

Figure 1.

Nursing Assistant Focus Group Guide for Technology Diverse Nursing Homes

Focus Group Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic data. All data were reported in aggregate to protect staff identity. Verbatim transcripts of digital recordings, initially created in Microsoft Word, were imported into NVivo 10.0 (QSR International, 2013) and used for thematic analysis. Imported files were stratified in NVivo by shift and NH IT sophistication level (HIGH, MEDIUM, LOW). Data were continually organized and reorganized line by line, creating a cohesive, comprehensive set of descriptors.

In NVivo, coded data are organized into nodes, called descriptors, which help identify emerging themes. Qualitative data coded in the nodes is used to respond to the specific aim and research questions. Furthermore, we anticipated NAs discussing specific types of communication strategies because of the focus of our interview questions. During our analysis we maintained detailed lists of the types of strategies that were discussed as well as how the strategies influenced communication with other staff and patients. To improve auditability and credibility of results, 2 graduate PhD nursing students with relevant experience assisted during coding, organization of nodes, and characterizing emerging themes (Barroso, 2010).

Results

Focus Groups and Participants

We conducted 31 focus groups, including 213 NAs. Table 2 contains a list of total participants, in each facility, by CNA job role, IT sophistication level, and average experience in years. The range of total participants for all 3 IT sophistication levels was 63-81. Participants had multiple roles and range of experiences. The range of experience was from just over 6 months, including 15 non-certified NAs in training, to a NA with nearly 39 years of experience.

Table 2.

Focus Group Participant by Job Role and Years of Experience

| Total Participants by IT Sophistication | Average Experience (Years) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Role(s) | Low | Medium | High | Total | |

| Certified NA (CNA) | 50 | 52 | 48 | 150 | 7.6 |

| CNA Restorative Aide | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 7.0 |

| CNA/Shower Aide | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 12.0 |

| CNA/Medication Technician | 2 | 5 | 10 | 17 | 14.1 |

| CNA/Medication Tech/IT Superuser | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 23.0 |

| NA (Non certified) | 2 | 6 | 7 | 15 | 0.6 |

| CNA/Activities Director | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 38.5 |

| Medication Technician | 6 | 3 | 6 | 15 | 18.5 |

| CNA/Medication Tech/Restorative Aide | 2 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 9.4 |

| 63 | 69 | 81 | 213 | ||

Focus Group Results

Types of communication strategies

Nursing assistants described a variety of communication strategies, based on NH IT sophistication level. Table 3 lists type of communication strategies in NH with HIGH IT sophistication, including use of electronic communication with electronic health records compared to NH with MEDIUM and LOW IT sophistication that had minimal use of electronic information systems, such as, IT systems used to document daily personal care. Other low tech systems included mail systems, laminated images and colored stickers, communication books, paper notes and checklists. In our assessment of the data, the medium group looks more like the low group. For example, IT sophistication scores on all domains were more than 3 × higher for high versus medium and low NH (see Table 1). Furthermore, the medium tech homes were not all that sophisticated. They incorporated many more non-electronic means of communication in their nursing care than electronic. Therefore, MEDIUM and LOW IT sophistication NH were grouped together for this report. The primary difference between HIGH IT and MEDIUM and LOW IT sophistication NH is that facilities with medium to low IT sophistication used electronic information systems only for personal daily care documentation which was conducted mostly by NAs. These low tech systems were isolated from other parts of the health record, and was not consistently used by NAs. All facilities had some form of electronic means to collect Minimum Data Set information; however, in the NH with the very lowest IT sophistication, these were not used by NAs for documentation of patient care, but mostly were used for administrative activities.

Table 3.

Communication Strategies Reported by Nursing Assistants in HIGH, MEDIUM and LOW IT Sophistication NH

| Types of Communication | Strategies in High IT Sophistication NH |

Strategies in Medium and Low IT Sophistication NH |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Communication | Electronic Health Record | Information System for Daily Personal Care |

| Highlighted Comments | Activities of Daily Living | |

| Red flags on messages | Patient movement | |

| Pink active interventions | Transfer type | |

| Grey inactive interventions | Percentage of meals eaten | |

| Interventions acknowledged | Sleeping | |

| Assessments | Confusion | |

| Skin | Showers or bed bath | |

| Daily Activity | Input and output | |

| Status boards | Continence | |

| NA assignments | Bowel movements | |

| Paging systems | Sleeping schedules | |

| Care instructions | Vital signs | |

| Protocols | Pressure relieving devices | |

| Turning schedules | Turn/reposition schedule | |

| Devices and Transfer information | ||

|

| ||

| Email access from home | ||

| Standard Mailbox | Standard Mailbox | |

|

| ||

| Laminated images/colored dots | Risk Status | Lifting Procedures |

| Skin | Hoyer | |

| Fall | Assist to stand | |

| Aspiration | Independent | |

| Prevention Measures | Self-care | |

| Isolation | Bracelet (Risk Identification) | |

| Handwashing | Reminders | |

| Positioning | ||

| Nutritional Needs | ||

| Hydration | ||

| Swallowing | ||

| Care Needs | ||

| Mobility | ||

| Skin | ||

| Moisturizers | ||

| Alarms/Alerts | ||

| Special Programs | ||

| Walk to dine | ||

| Communication Books | Patient Care Lists | NA book |

| First down/Last up | Daily reports | |

| Bowel movement | Team assignments | |

| Skin issues | Shower schedules | |

| Nursing talk book | Time resident up | |

| Report book | Time resident down | |

| Toileting | ||

| Monthly reports | ||

| Transfer information | ||

| Ambulation | ||

| Bowel movements | ||

| Walk to dine | ||

| Dentures | ||

| Briefs | ||

| NA spiral notebooks | ||

| Care plan book | ||

|

| ||

| Paper Notes, Checklists, Reports | Daily huddle and huddle sheet | Care Tracking |

| Notes above the bed | Skin issue/severity tracking | |

| 24 hour report | Input/output sheets in closet | |

| Pressure Ulcer List | Turn/Repositioning | |

| Information sheets in closet | Daily activities (Therapy/Showers) | |

Electronic communication types in MEDIUM and LOW IT NH were isolated systems and not highly integrated into resident care (see Table 1). Communication strategies were robust in HIGH IT sophistication facilities with several more types of communication in these NH, including electronic and other forms that were integrated across disciplines. HIGH IT sophistication NH had greater integration with other internal and external data sources that were used by NAs, too (see Table 1). For example, documentation about devices and transfer information in the electronic medical record were available for physical therapy as well as nursing. Integration of interdisciplinary documentation provided a more complete picture for NAs accessing electronic systems to help them make decisions about what types of devices and transfer equipment to assist them when ambulating residents.

Emerging themes

In this analysis, coded data represented in descriptive nodes captured three major themes in which IT, or lack thereof, influenced how NAs described communication strategies about pressure ulcer prevention and how skin care is prioritized in these facilities, including: 1) passing on information, 2) keeping track of needs and 2) information access.

Passing on information

Descriptions of strategies used by NAs included (n=401) statements about resources that were used to facilitate communication and sharing information about pressure ulcer prevention and skin care measures taken (see Table 3). These strategies were described as critical components for processes required to pass on information, between different nursing staff, so continuity of care was maintained, and so care could be prioritized. Robust communication systems, including electronic communication forms, increased the complexity of how information was passed along from person to person, but provided greater opportunities for messages to reach their intended targets, such as NAs. Additional low tech communication strategies discussed (i.e. Laminated images and colored dots posted on door frames, centralized communication books, and paper notes with checklists) were less sophisticated, but still critically important to spread information about pressure ulcer risk, prevention measures, and timing of care delivery.

Keeping Track of Resident’s Needs

The descriptor Keeping Track of Resident’s Needs contained the second most frequent number of coded references (n=365), made by NAs, during focus group discussions. In HIGH IT sophistication NHs, electronic intervention lists were frequently referenced as key strategies that “drive what the nurses and CNAs do”. The electronic intervention lists served several functions to help NAs keep track of resident needs. For example, intervention lists contain, “Wound treatments, shower schedules, anything that happened overnight, communication from nurse to nurse, and notes to NAs from nurses.” One participant described how these intervention lists can be used to prioritize care: “When you click on a certain box in the intervention list on the computer, it will tell the NAs what the task is. There is a box that pops up and NAs can comment on it. For example, they ‘got the message’, or if a particular patient needs turning at a certain time, the NAs can document that they did the tasks.”

In all groups of facilities, HIGH, MEDIUM and LOW IT sophistication, NAs discussed important work foundations. One NA stated, “...what NAs do is common knowledge…there are some things that NAs automatically know to do [such as] turning, good peri-care, barrier cream.” One main difference emerging from staff conversations in these facilities were the types of care activities being reported. In HIGH IT sophistication facilities, where electronic communication strategies were more common, one NA indicated, “the computer is great, because that allows the nurses to give the NAs a ‘heads up’ on issues. The nurses know that the NAs know what to do, but by the NAs clicking on the pink box, that lets the nurse know that the NAs are aware and are following the protocols. [The box] will turn from pink to white when the NAs clicks on the box as a way of acknowledging reading the pink box and doing what it says to do.” In multiple references, highlighting important information in a report was a critical part of notifying NAs about appropriate care delivery. These enhancements helped NAs to recognize high priority areas of care. Additionally, communication strategies, including pop up reminders, provided a means to electronically report important information located in a health record versus searching in the various communication notebooks used by all facility types.

Electronic communication systems, in HIGH sophistication facilities, enabled staff to keep up to date on the status of patient care delivery, from anywhere in the facility, as long as a computer was available. Sometimes staff even communicated from home using electronic email systems. A Status Board feature was accessible to all NAs. The Status Board provided a mechanism to track patient needs in the same shift and across shifts. One NA described this functionality, “All NAs have access to the Status Board, so if something is not told verbally and is forgotten, the next shift can see the Status Board when they log into their shift. There are red-flagged areas on the Status Board for special NA instructions per patient, if needed.” Status boards and intervention lists were required to be completed by NA staff on each shift. Completion of status boards and intervention lists were tracked by nurses responsible for coordinating patient care, so they knew when care delivery had been documented. Interactive color coded status boards and intervention lists enhanced tracking of care needs between nurses responsible for patient care and their assistants providing care.

In contrast, staff in MEDIUM and LOW IT sophistication facilities used paper communication notebooks that incorporated daily and monthly reports to share important information. One NA described this process, “The communication notebook is just a notebook that they use. If someone runs across something that is important, they write down the information in the notebook. Staff looks in the book from the previous shifts to find out things they need to know. It’s just used as communication. In case you missed out on something, you can look in the book.” These types of communication strategies provided less structure about what and when something was documented. For example, one NA was, “not sure if they would write down about turning.” In the MEDIUM and LOW IT sophistication facilities, NAs appear to have greater reliance on intuition, experience, and communication to keep track of residents’ needs. Similar to the intervention list, one MEDIUM and LOW IT sophistication facility used a “run sheet” as a communication strategy in the NAs notebook. This run sheet was described as,

“…a grid format and has all the patient’s names in it and gives information on how the patient transfers, how much assistance they need, if a lift is needed, toileting, briefs, diet, ted hose, alarms, side rails, devices, low bed, dentures, and glasses. [The run sheet] is not a check off; it is more for information.”

Information access

The third theme materializing from our data was associated with data in the descriptor titled NAs reports (n=290 references). Much of the data associated with this descriptor was associated with how NAs reports were integrated into patient care to support communication about pressure ulcer prevention measures. Table 3 lists types of communication books and reports that were used among all facilities, some electronic and some more traditional forms.

An underlying theme related to NAs reports referenced by many staff using non-computerized communication strategies related to notification or tracking current patient status. or history. Several NAs referenced that location of reports and information on reports were placed in highly visible areas to be used as reminders, regardless of IT adoption measures. For example, several different types of colorful laminated pictures were posted on door frames of patient rooms, indicating a variety of possible risks (e.g. fall), health conditions (e.g. dehydration), and necessary interventions (e.g. thickened liquids). These methods were used in all types of facilities. These sorts of reminders were used during walking rounds on the nursing units. For example, one NA in a high tech facility described some of these communication tools, “NAs look for the M & M on the door for people at risk of skin problems. It’s a picture of a candy M & M which stands for Moisture and Mobility. They use a leaf if someone is a fall risk. They use [colored] dots for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation or Do Not Resuscitate orders.” In absence of some type of mobile device, these door signs are a good adjunct to IT solutions to remind people of care needs.

Discussion

For a long time, NAs work has been recognized as an important part of quality improvement in NH (Bowers & Becker, 1992). However, the landscape in NH is different now as IT may facilitate communication between NAs and other care providers. Technology enables NAs to find relevant information quicker and allows them to communicate real-time about patient activities to nurses, so nurses can make better patient care decisions for NH residents. However, this paradigm shift will not be an easy transition for some organizations to make as traditional means of communication, which have typically not included NA documentation, can be difficult to change (Alexander, Rantz, Flesner, Diekemper, & Siem, 2007).

Our results demonstrate the potential value of more rigorous research about the effect of increasing IT sophistication on NA communication, specifically, linking nationally reported quality measures collected on all U.S. NHs with specific communication strategies, such as resident Activities of Daily Living, incontinence, or turning activities which are typically reported by NAs. Furthermore, it would be novel to explore these outcomes in the context of expanding shared information resources in NHs with greater IT adoption. For example, a useful study might explore enhanced NAs documentation with other electronically documented sources of patient information such as the wound care nurse and nutritional services (increased integration IT sophistication), workflows related to IT integration that enhances tracking and communication about resident’s skin care needs communicated between NAs and other NH staff (increased functional IT sophistication), and greater clinical decision support activities through the design and implementation of different types of patient care alerts, such as an alert for increasing incontinence associated with NAs documentation about toileting activities, to alert a nurse would be a valuable tool for detecting increased risk (increased clinical IT sophistication).

Historically, NAs observations and clinical knowledge have not been part of formal medical records. This is despite the fact that NAs in many ways extend the eyes and ears of professional nurses, who they are assisting (Castle et al., 2007). The NA’s role incorporates significant amounts of observation and ongoing monitoring of critical patient outcome measures, such as skin issues, that arise from incontinence, poor mobility, and decline in activities of daily living. Clinical IT systems not capable of capturing these crucial observations, made by NAs, are missed opportunities for nurses to make better clinical decisions and respond earlier to illness. Consider the NA who assists with skin care cleaning and lotion application several times a day, with an incontinent patient. In most of the communication systems (paper or electronic), NAs documentation includes information about timing of work and defines tasks completed for individual residents. However, little information is documented about the observations made of the skin after crucial NA observations of the patient. Current documentation systems both electronic and paper are incomplete, leaving out crucial observations made by other health care team members, such as NAs. Increasing NH IT sophistication provides an excellent resource for tracking needs, which have important implications for communication systems and patient outcomes. Further development and research is warranted for information system designs that incorporate all patient observations conducted. It will be important to include experienced NAs in the design of these new documentation systems to maximize their usability and acceptance.

Results demonstrate that a NAs and nurses ability to pass on information to other care givers, to track resident’s needs at the point of care, and ability to access information may affect workflow. Sophisticated IT that is well integrated into care processes should enhance clinical workflow, but there are few studies that include these types of measurements. Advanced clinical workflow measures are an important new and upcoming metric to determine technology’s influence on patient care delivery and quality (Carayon, Karsh, & Carmill, 2010). For instance, clinical IT has been promoted as a resource that can help all types of clinicians to get closer to the point of patient care. Clinical workflow metrics can quantify this relationship by calculating distance metrics between staff interactions and places where people conduct work. For example, clinical workflow metrics can help administrators visualize how information is shared between different types of staff, such as NAs and RNs. Further, these types of measures can help determine where basins of information are located and how that information spreads across an organization. Clinical workflow measures can provide visual metrics for different types of interactions, such as those between NAs and RNs, that are occurring, interaction frequency, and timing. Determining the effect of IT on clinical workflow using these measures will help to identify benchmarks for best practices of IT use in work processes, the role IT plays in quality improvement, and how workflow can be maximized to facilitate better patient care. Subsequently, these measures can be used to evaluate how improved clinical workflows and care design options, in care delivery, influences care quality. In the future, the use of IT in quality improvement efforts through tracking workflow and patient/staff interactions about pressure ulcer prevention will be an extension of this work.

Focus groups can be a challenge to conduct because it can be difficult for groups of people being interviewed to reach consensus or there could be irrelevant discussions from the main topic being discussed. To overcome these challenges, we consistently used a structured set of open ended questions, questions were current and relevant to the NAs job role, and questions were free of technical jargon. We encouraged clarifying questions by participants, which set a tone of openness and sharing, while maintaining complete confidentiality of shared experiences discussed. These methods helped us to gather some opinions and perceptions of how IT adoption influences communication strategies and quality of care in these facilities.

In the few studies, linking IT adoption with NH quality measures, some measures appear to be influenced by increasing IT adoption, like decline in activities of daily living, incontinence, and pressure ulcer outcomes (Rantz et al., 2010). The association between increasing clinical IT and relationships to patient outcomes was not measured in this analysis. More rigorous research is needed before any cause and effect between increasing IT sophistication and improved quality measures, can be determined. Evidence from our research lends support that IT may have an association to quality, because in NH with high IT sophistication there are more robust communication strategies, increased efficiencies in tracking clinical work, and enhanced information sharing between nursing and NAs about care delivery (Alexander et al., in press).

This study took place in only one state; however, we recruited a large diverse sample enhancing the generalizability of this study to other NH with similar types of communication strategies.

In this study NA staff provided a rich qualitative data set describing the communication strategies deployed in 16 NH facilities in Missouri. Conversations resulted in identification of three major themes. The most referenced theme was passing on information, followed by keeping track of needs, and information access. NAs communication is important in the care of the 1.5 million elderly residents in NH. Communication strategies deployed in NH are crucial to the outcomes of these residents.

Acknowledgments

NOTES: This project was supported by grant K08HS016862 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (PI: G. L. Alexander). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Reference List

- Ahn H, Stechmiller J, Horgas A. Pressure ulcer related pain in nursing home residents with cognitive impairment. Advances in Skin and Wound Therapy. 2013;26:375–380. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000432050.51725.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GL, Madsen R. IT sophistication and quality measures in nursing homes. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2009;35:22–27. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20090527-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GL, Madsen D, Herrick S, Russell B. Measuring IT sophistication in nursing homes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. (Report No. 08-0034-CD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GL, Madsen R, Wakefield DS. A regional assessment of information technology sophistication in Missouri nursing homes. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice. 2010;11:214–225. doi: 10.1177/1527154410386616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GL, Pasupathy K, Steege L, Strecker E, Carley K. Multidisciplinary communication networks for skin risk assessment in nursing homes with high IT sophistication. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2014;83:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GL, Rantz MJ, Flesner MK, Diekemper M, Siem C. Clinical information systems in nursing homes: An evaluation of initial implementation strategies. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2007;25:189–197. doi: 10.1097/01.NCN.0000280589.28067.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GL, Steege L, Pasupathy K, Strecker EB. Case studies of IT sophistication in nursing homes: A mixed method approach to examine communication strategies about pressure ulcer prevention practices. International Journal of Industrial Engineering (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GL, Wakefield DS. IT sophistication in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2009;10:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso J. Qualitative approaches to research. In: LoBiondo-Wood G, Haber J, editors. Nursing research. 7th. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2010. pp. 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers B, Becker M. Nurses aides in nursing homes: The relationship between organization and quality. The Gerontologist. 1992;32:360–366. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Karsh BT, Carmill RS. Incorporating health information technology into workflow redesign–Summary report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. (Report No. 10-0098-EF). [Google Scholar]

- Castle NG, Engberg J, Anderson R, Men A. Job satisfaction of nurse aides in nursing homes: Intent to leave and turnover. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:193–204. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry B. Assessing organizational readiness for electronic health record adoption in long term care facilities. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2011;10:14–19. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20110831-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke H, Bradley C, Whytock S, Handfield S, van der Wal R, Gundry S. Pressure ulcers: Implementation of evidence-based nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49:578–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety. Key capabilities of an electronic health record system. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellefield ME, Harrington C, Kelly A. Observing how RNs use clinical time in a nursing home: A pilot study. Geriatric Nursing. 2012;33:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossum M, Alexander GL, Ehnfors M, Ehrenberg A. Effects of a computerized decision support system on pressure ulcers and malnutrition in nursing homes for the elderly. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2011;80:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossum M, Alexander GL, Goransson KE, Ehnfors M, Ehrenberg A. Registered nurses’ thinking strategies on malnutrition and pressure ulcers in nursing homes: A scenario-based think-aloud study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011;20:2425–2435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin S, Georgiou A, Barton D, Westbrook J. Examining the role of information exchange in residential aged care work practices-A survey of residential aged care facilities. BMC Geriatrics. 2012;12:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorecki C, Brown JM, Nelson EA, Briggs M, Schoonhoven L, Dealey C, Nixon J. Impact of pressure ulcers on quality of life in oder patients: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:1175–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment protocol. Health care protocol. Bloomington, MN: Author; 2012. (Report No. NGC-8962). [Google Scholar]

- Long term care and technology. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Author; 2012. (International Federation on Aging). [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Samore MH, Carter M, Rubin MA. Long term care facilities in Utah: A description of human and information technology resources applied to infection control practice. American Journal of Infection Control. 2012;40:446–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBiondo-Wood G, Haber J. Nursing Research. 7th. St. Louis: Mosby; 2010. Introduction to Qualitative Research; pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Munyisia EN, Yu P, Hailey D. The impact of an electronic nursing documentation system on efficiency of documentation by caregivers in a residential aged care facility. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21:2940–2948. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare G, Sicotte C. Information technology sophistication in health care: An instrument validation study among Canadian hospitals. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2001;63:205–223. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(01)00178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian SY, Yu P, Zhang ZY, Hailey D, Davy PJ, Nelson MI. The work pattern of personal care workers in two Australian nursing homes: A time motion study. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo (Version 10) [Computer software] 2013 Available from http://www.qsrinternational.com/

- Rantz MJ, Hicks L, Petroski GF, Madsen RW, Alexander GL, Galambos C, Greenwald L. Cost, staffing, and quality impact of bedside electronic medical record (EMR) in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2010;11:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HE, Manard BB, Stone RI, Alwan M. Use of electronic information systems in nursing homes: United States, 2004. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2009;16:179–186. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittig DF, Singh H. Electronic health records and national safety patient goals. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:1854–1860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1205420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens KR, Staley JM. The quality chasm reports, evidence based practice, and nursing response to improve healthcare. Nursing Outlook. 2006;54:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan N, Schoelles KM. Preventing in-facility pressure ulcers as a patient safety strategy: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;158:410–416. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelsmeier AA, Halbesleben JRB, Scott-Cawiezell JR. Technology implementation and workarounds in the nursing home. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2008;15:114–119. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Yu P, Hailey D. Description and comparison of quality of electronic versus paper-based resident admission forms in Australian aged care facilities. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2013;82:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich GS, Kohler PO, editors. Improving the quality of long term care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Li H, Gagnon MP. Health IT acceptance factors in long-term care facilities: A cross sectional survey. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2009;78:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Shen J. The benefits of introducing electronic health records in residential aged care facilities: A multiple case study. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2012;81:690–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]