Abstract

Objective

HIV-infected women are burdened by depression and anxiety, which may impact adherence to antiretroviral therapy and overall quality of life. Yet, little is known about the scope of psychological symptoms in the growing number of HIV-infected women reaching menopause, when affective symptoms are more prevalent in the general population. We conducted a longitudinal study to compare affective symptoms between perimenopausal HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected women.

Methods

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) were completed at baseline and 12 months among 33 HIV-infected and 33 non-HIV-infected perimenopausal women matched by race, age, menstrual patterns, and BMI. Linear regression models estimated the relationship of baseline GAD-7 and CES-D scores with clinical factors.

Results

All women were perimenopausal at baseline and the vast majority remained perimenopausal throughout follow-up. HIV status was associated with higher baseline CES-D scores (median (interquartile range), (21 (12,29) vs. 10 (5,14), p=0.03) and GAD-7 scores 7 (5,15) vs. 2 (1,7), p=0.01), controlling for smoking, substance use, and antidepressant use. Depressive symptoms and anxiety remained significantly higher in the HIV-infected women at 12 months (p≤0.01). Significant relationships of depressive symptoms (p=0.048) and anxiety (p=0.02) with hot flash severity were also observed.

Conclusions

Perimenopausal HIV-infected women experienced a disproportionately high level of affective symptom burden over a 12-month observation period. Given the potential for these factors to influence adherence to HIV clinical care and quality of life, careful assessment and referral for treatment of these symptoms is essential.

Keywords: HIV, Perimenopause, Depression, Anxiety, Hot Flashes

Introduction

More women with HIV are reaching midlife and experiencing menopause than ever before, as the proportion of older women with HIV in the U.S has more than tripled in the past decade1. The psychological symptoms of menopause warrant investigation among the growing population of HIV-infected women, many of whom are disproportionately burdened by depression and anxiety in their earlier adult life2,3,4. A recent mixed cohort study of HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected women found that depressive symptoms were elevated among all women in early perimenopause, and depressive symptoms associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy among the HIV-infected women5. Thus, an understanding of the affective symptoms of midlife HIV-infected women is essential to optimize the health of this population, and develop strategies to support adherence to HIV clinical care.

Women are susceptible to both mood and anxiety symptoms at midlife. Indeed, increased risk for the development of depressive symptoms has been observed during the menopause transition, particularly among women with a history of minor or major depressive disorder6,7. Prior large cohort studies of non-HIV-infected women have determined that perimenopausal women are at three times greater risk of experiencing depressive symptoms compared to premenopausal women8. Similarly, anxiety symptoms are also more prevalent among women at midlife, even among women who have low levels of anxiety prior to the menopause transition9.

In non-HIV-infected women, the etiology of depressive symptoms and anxiety in relation to the menopause transition is multi-factorial, and has been attributed to hormonal changes, vasomotor symptoms, sleep disturbance, and stressful life events10–12. We have shown previously that perimenopausal HIV-infected women experience greater hot flash severity and hot flash-related interference with daily function compared to perimenopausal non-HIV-infected women13. Bothersome hot flashes may influence the development or existing state of depression or anxiety in women with HIV, though this remains largely unexplored in this population. This paucity of research has negative implications on the clinical evaluation and treatment of depression and anxiety in the growing population of HIV-infected women at midlife, and the potential for broader implications on promoting health for this population, such as adherence to HIV clinical care.

This longitudinal study was designed to prospectively evaluate affective symptoms in a cohort of perimenopausal women with and without HIV, over a period of 12 months. We hypothesized that depression and anxiety scores would be higher among HIV-infected women at baseline and would remain stable and elevated over 12 months, compared to the symptom levels in the non-HIV-infected women. As an extension of our prior cross-sectional analysis13, we also evaluated longitudinal differences in menopause symptom severity and hot flash-related daily interference in this cohort. We hypothesized that menopause symptoms and hot flash-related daily interference, previously reported to be more severe in perimenopausal HIV-infected women relative to perimenopausal non-HIV-infected women13, would continue to remain elevated in the HIV–infected women at 12 months. The relationship between hot flash characteristics and depression and anxiety scores was evaluated to examine the potential association of affective symptom burden with vasomotor symptom levels.

Methods

Participants

A cross-sectional investigation of hot flash severity and hot flash-related interference with daily function was previously published among this cohort of sixty-six perimenopausal women with and without HIV (33 HIV-infected and 33 non-HIV-infected women)13. The current study evaluates the 12-month longitudinal data on depression, anxiety, and menopause symptoms, in that same cohort. Eligibility criteria were previously described13. Briefly, women were between the ages of 45 and 52 years, and perimenopause status was classified as presence of 1 menstrual cycle greater than 60 days in length in the past 6 months, or irregular menses in 2 or more menstrual cycles in the past 6 months14. Women were not eligible if they were amenorrheic for 12 months or longer, had a hysterectomy, had active cancer, had used hormone therapy in the past 6 months, or were pregnant or breastfeeding. Women with HIV were required to be on a stable HIV treatment regimen for at least 3 months prior to study enrollment and did not experience an opportunistic infection during this period. Women were recruited for the study by posting flyers and newspaper ads at HIV community organizations and outpatient clinics. A hospital-based research participant data registry that includes patients interested in learning about research studies also served as a recruitment method. Participants received $100 for participation. A stratification algorithm13 was used to recruit women without HIV who were similar in age, race, and menstrual patterns to the women with HIV. Careful attention was also paid to matching participants on body mass index (BMI). This study was reviewed and approved by the Partners Healthcare institutional review board, Boston, MA.

Data Collection

The primary data were collected at baseline and 12 months. At each time point, depression, anxiety, and menopause symptoms were assessed using standardized self-reported measures, and data on general and HIV-related health, and medication usage (including current use of antidepressants and anxiolytics) were obtained. Participants were also asked if they had ever been diagnosed with depression or anxiety by a professional. Menstrual bleeding frequency over the prior 6 months was re-assessed at a brief 6-month assessment and again at the 12-month visit. Twenty-seven HIV-infected women and 30 HIV-negative women had menstrual history data available at the 6- and the 12-month visit. At baseline, women were also asked to report number of days with hot flashes in the past month. Baseline estradiol and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) were measured via Access Chemiluminescent Immunoassay (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California). CD4 cell count was measured via flow cytometry (MultiTEST CD3 FITC/CD8 PE/CD45 PerCP/CD4 APC reagent, Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, California). HIV viral load, HIV-1 RNA, was measured by real-time PCR, Quantitative (Cobas® AmpliPrep/Cobas® TaqMan® HIV-1 Test, Version 2.0; Roche Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA). Missing values are present for CD4 count (n=7) and HIV viral load levels (n=11), due to poor venous access or insufficient blood collection volume.

Questionnaires

Mood Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item scale used widely to assess depressive symptom severity15. Participants were asked to describe frequency of each depressive symptom component experienced during the past week (rarely or none of the time; some or little of the time; occasionally or a moderate amount of the time; most of the time). Total scores range from 0–60, with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology. A total CES-D score greater than or equal to 16 indicates depressed mood and increased risk for clinical depression16.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) was completed to measure symptoms of anxiety17. Participants were asked to describe how frequently they were bothered by specific anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Item responses range from 0–3 (not at all, several days, more than half the days, nearly every day), and total scores range from 0–21, with higher scores indicative of greater anxiety (0–4 indicates minimal anxiety, 5–9 indicates mild anxiety; 10–14 indicates moderate anxiety; 15–21 indicate severe anxiety17).

Menopause Symptoms

The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) was used to measure presence and severity of menopause symptoms experienced “at this time”. The item response scale for each of the questions ranges from 0–4 (none, mild, moderate, severe, extremely severe), with total MRS scores ranging from 0 or asymptomatic, to 44 or highest degree of complaint18,19. Item 1 of the MRS was used to determine hot flash severity. The Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale (HFRDIS) was used to evaluate the impact of hot flashes on daily activities and quality of life during the past week. The item response for each of the 10 questions ranges from 0 (do not interfere) to 10 (completely interfere), with the total HFRDIS score ranging from 0–100 (higher score represents greater interference)20.

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality of the study variables. Normally distributed data were summarized as mean ± standard deviation, and non-normally distributed data were reported as median (interquartile range, IQR).

Student’s t-tests were performed to compare differences in normally distributed outcomes between the HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected women; non-normally distributed data were compared by the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test, and are presented as percentages/numbers. Within-group (HIV and non-HIV-infected women) changes in symptom scores over 12 months were compared using Paired t-tests, and between-group comparisons of within-group change from baseline to 12 months were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Linear regression models were created to estimate the relationship between the dependent variables (baseline CES-D score and GAD-7 score) and explanatory variables at baseline, and 95% confidence intervals about estimated effects were computed. First, univariable models were created for the CES-D score and the GAD-7 score, controlling for HIV status. Next, multiple regression modeling was performed for the CES-D score and separately for the GAD-7 score. Both models adjusted for explanatory variables that differed between the HIV and non-HIV groups, including current smoking status, substance abuse history, and current use of antidepressant medication. A separate set of purposeful models were also generated to evaluate the association between hot flash characteristics and baseline CES-D and GAD-7 scores in the study sample. Both models adjusted for vasomotor symptom characteristics including number of days with hot flashes in the past month, and hot flash severity (MRS item 1), respectively. Smoking status was added to this model as it is known to influence hot flashes21. For the purpose of this analysis, MRS item 1 was dichotomized (presence of moderate, severe or extremely severe hot flashes versus none or mild hot flashes), and post-hoc analyses were conducted to determine equal distribution among this dichotomized hot flash severity variable (n=66; 31 (47%) reported none or mild hot flashes; n=35 (53%) reported moderate, severe, or extremely severe hot flashes). Collinearity was assessed in each model by performing backwards/forwards selection of each covariate with HIV status, and the overall parameter estimate for HIV status remained generally stable within in all models. Assumptions of linear regression in all models were also assessed using graphical methods including quantile-quantile and variance plots.

In a subgroup analysis among HIV-infected women only, univariable models were created in parallel for the GAD-7 and CES-D scores measured at baseline, and HIV-specific characteristics including duration of HIV (years) and current antiretroviral therapy use. HIV viral load and CD4 count were not included in these models due to a high proportion of the study sample having missing data on these HIV disease status markers.

This investigation among 66 women had power to detect a 0.7 SD difference between the groups, with statistical power of 0.8 and a two-sided 0.05 significance level13. Analyses were conducted with SAS JMP statistics software (version 12; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Study Participants

Baseline characteristics of the 66 women (33 HIV-infected and 33 non-HIV-infected) are presented in Table 1. As described previously13, the groups did not differ in age, race, or menstrual patterns; and the mean duration of HIV was 14±6 years. Most women remained perimenopausal throughout the study, with only 3 (10%) of the non-HIV-infected women and 5 (19%) of the HIV-infected women with available data reporting not having any menstrual periods during the 12-month follow-up (p=0.36). Significant differences were not observed regarding history of a diagnosis of anxiety or depression, or current use of anxiolytics at baseline. However, a greater number of HIV-infected women reported current antidepressant use (48% versus 18%, p=0.009).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Demographics | HIV + (N= 33) | HIV – (N= 33) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47 (45,48) | 47 (46,49) | 0.06 |

| Older than the median split % (#) | 33% (11) | 45% (15) | 0.31 |

| Race: %(#) | |||

| Nonwhite | 64% (21) | 52% (17) | 0.32 |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 15% (5) | 12% (4) | 0.72 |

| Body Mass Index | 28.6±6.5 | 28.7 ± 5.6 | 0.98 |

| Current Smoker % (#) | 70% (23) | 42% (14) | 0.03* |

| History of Substance Abuse % (#) | 76% (25) | 36% (12) | 0.001** |

|

| |||

| Menopause characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Total Number of Menstrual Periods in the Past Year | 5 (4,9) | 6 (4,10) | 0.53 |

| Follicle Stimulating Hormone (mIU/mL)a | 24 (8,53) | 35 (15,63) | 0.19 |

| Serum Estradiol (pg/mL)b | 60 (32, 206) | 81 (44,154) | 0.61 |

|

| |||

| Mental health characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| History of Depression % (#) | 76%(25) | 64% (21) | 0.28 |

| Current use of Antidepressantsc % (#) | 48% (16) | 18% (6) | 0.009** |

| History of Anxiety % (#) | 42% (14) | 39% (13) | 0.80 |

| Current Use of Anti-anxiety Medications % (#) | 6% (2) | 6%(2) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| HIV | |||

|

| |||

| Duration of HIV (years) | 14±6 | - | - |

| Currently taking Antiretroviral Therapy % (#) | 91% (30) | - | - |

| Current NRTI use | 91% (30) | - | - |

| Current NNRTI use | 9% (3) | - | - |

| Current PI use | 45% (15) | - | - |

| CD4 count (#/mm3)d | 686±432 | - | - |

| Nadir CD4 count (#/mm3)e | 199 (60,290) | - | - |

| Undetectable HIV Viral Loadf | 77% (17) | ||

Data are reported as % (n) for categorical variables, and for continuous variables, as mean/SD or median (IQR=interquartile range) for data that were not normally distributed.

=P<0.05,

=P<0.01.

Missing values are not included in the calculation: n=2,

Missing values: n=3,

Antidepressant medications include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use (SSRI) and other types of antidepressant medication,

Missing values: n=7,

Missing values: n=3,

Missing values: n=11.

PI= protease inhibitor; NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. This table is an adapted version of the Table 1 previously published in our original manuscript13.

Affective and Hot Flash Symptoms at Baseline

The HIV-infected women had significantly higher CES-D scores, that were nearly twice as high as the non-HIV-infected women (median 21, IQR 12, 29) vs. 10 (5, 14), p=0.0006). Similarly, the proportion of HIV-infected women with CES-D scores ≥ 16 was substantially greater than non-HIV-infected women (67% vs. 21%, p=0.0002; Table 2), suggesting the possibility of a higher prevalence of clinical depression. In addition, the HIV-infected women had higher GAD-7 scores (median (interquartile range, IQR), 7 (5, 15); indicating mild anxiety), compared to non-HIV-infected women (2 (1, 7), reflecting minimal anxiety, p=0.0003; Table 2).

Table 2.

Menopause and Mood Symptoms at Baseline and 12 Months

| Baseline | 12 Months |

Between- Group Change over 12 Ma |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mood Symptoms | HIV + (N= 33) | HIV – (N= 33) | P-Value | HIV+ (N=31) | HIV− (N=32) | P-Value | P-Value |

| Total Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale | 21 (12,29) | 10 (5,14) | 0.0006** | 19 (10,31) | 10 (5,19) | 0.005** | 0.89 |

| CESD Score ≥ 16 % (#) | 67% (22) | 21% (7) | 0.0002** | 61% (19) | 41% (13) | 0.10 | |

| Total General Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale | 7 (5,15) | 2 (1,7) | 0.0003** | 9 (5,14) | 3 (0,7) | 0.001** | 0.89 |

|

| |||||||

| Menopause Symptoms | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Total Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) | 15 ± 8 | 10 ± 7 | 0.008** | 17 ± 8 | 11 ± 7 | 0.002** | 0.59 |

| MRS Item 1: Hot Flash Severity | 2 (1,3) | 1 (0,3) | 0.03* | 2 (1,3) | 1 (0,2) | 0.09 | 0.41 |

| Total Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale | 37 (10,60) | 6 (0,20) | 0.001** | 36 (19,53) | 8 (0,27) | 0.001** | 0.99 |

Data are reported as % (n) for categorical variables. Normally distributed data are reported as mean/SD and non-normally distributed data are presented as median (IQR=interquartile range).

=P<0.05,

=P<0.01.

Represents between-group change (HIV+ vs. HIV−) at 12 months. Within group change for both HIV+ and HIV− women at 12 months was not significant (P= > 0.05) for each variable (MRS, MRS item 1, HFRDIS, GAD-7, and CES-D). Baseline data for the MRS, MRS item 1, and HFRDIS were previously published13

Data showing higher menopause symptom questionnaire scores (MRS and HFRDIS) at baseline in the HIV than the non-HIV women are presented in Table 2 and were previously published13. Sixty-seven percent (22) of the HIV-infected women compared to 42% (14) of the non-HIV-infected women reported having a greater number of days with hot flashes in the past month (hot flashes 8 or more days [median split] in the past month at baseline; p=0.048)13.

Affective Symptoms at 12 Months and Longitudinal Changes from Baseline to 12 Months

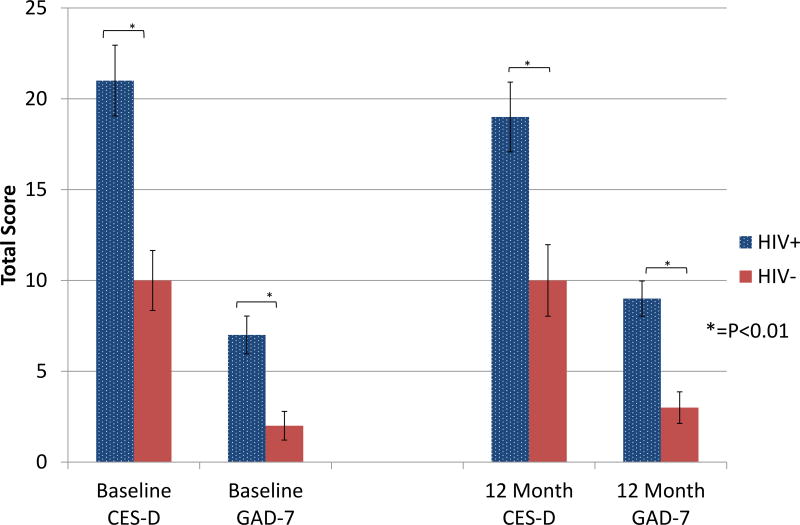

Two HIV-infected women and 1 non-HIV-infected woman were lost to follow-up at 12 months. Both of the affective symptoms questionnaire scores (CES-D, GAD-7) as well as the menopause symptoms questionnaire scores (MRS, HFRDIS) remained significantly higher in the HIV-infected women versus the non-HIV-infected women at 12 months (p<0.01 for all variables; Table 2, Figure 1), whereas the hot flash severity (MRS item 1) score showed a statistical trend (p=0.09) toward a higher score in the HIV group at 12 months. The total scores for each questionnaire and MRS item 1 remained generally stable from baseline to 12 months, without significant differences in questionnaire scores between or within each group over the 12-month period (HIV-infected verse non-HIV-infected, p>0.05 for all analyses; Table 2). The proportion of individuals with CES-D scores indicative of clinical depression was not statistically different between groups at 12 months (61% vs 41%, p=0.10).

Figure 1. Comparison of Mood and Anxiety Symptoms at Baseline and 12 Months.

Perimenopausal HIV-infected women had significantly higher CES-D scores and GAD-7 scores compared to perimenopausal non-HIV-infected women at baseline and 12 months (P<0.01 at both time points).

Predictors of Affective Symptoms at Baseline

In univariable linear regression models, HIV-infected women were estimated to have baseline mean CES-D scores 4.8 points higher than the non-HIV-infected women (p=0.0004), and mean GAD-7 scores 2.5 points higher than non-HIV-infected women (p=0.0003), reflecting higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively (Table 3a & 3b). After controlling for current smoking status, history of substance abuse, and current antidepressant use, HIV-infected women were still estimated to have a mean CES-D score 3.0 points higher than the non-HIV-infected women (p=0.03), and a mean GAD-7 score 1.9 points higher than non-HIV-infected women (p=0.01) (Table 3a & 3b).

Table 3.

a. & 3b: Baseline Associations with Mood and Anxiety Symptoms

| a. Univariable and Multivariable Associations with Total CES-D Score in Perimenopausal HIV-infected and non-HIV infected Women (n=66) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||||

| R2 = 0.18, P=0.0004 | β-estimate | 95% CI | P-value | R2 = 0.29, P=0.0003 | β-estimate | 95% CI | P-value |

| HIV Infection (yes) | 4.8 | [2.2,7.3] | 0.0004 | HIV Infection (yes) | 3.0 | [0.2,5.7] | 0.03 |

| Current Smoking (yes) | 1.6 | [−1.4,4.7] | 0.29 | ||||

| History of Substance Abuse (yes) | 2.7 | [−0.4,5.8] | 0.09 | ||||

| Current Antidepressant Use (yes) | 1.0 | [−1.8,3.8] | 0.49 | ||||

| b. Univariable and Multivariable Associations with Total GAD-7 Score in Perimenopausal HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected Women (n=66) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||||

| R2 = 0.18, P=0.0003 | β-estimate | 95% CI | P-value | R2 = 0.24, P=0.002 | β-estimate | 95% CI | P-value |

| HIV Infection (yes) | 2.5 | [1.2,3.8] | 0.0003 | HIV Infection (yes) | 1.9 | [0.4,3.3] | 0.01 |

| Current Smoking (yes) | 0.7 | [−0.9,2.3] | 0.38 | ||||

| History of Substance Abuse (yes) | 0.1 | [−1.5,1.8] | 0.88 | ||||

| Current Antidepressant Use (yes) | 1.2 | [−0.3,2.7] | 0.12 | ||||

The purposeful multivariable models (Table 4a & 4b) adjusted for HIV status, hot flash severity, number of days with hot flashes in the past month, and smoking. Three covariates were identified to have independent, significant associations with baseline CES-D scores. HIV-infected women were estimated to have a 3.0 point higher mean CES-D score compared to non-HIV-infected women (p=0.02). Women with moderate, severe or extreme severe hot flash severity were estimated to have mean CES-D scores 3.1 points higher than women who reported none or mild, hot flash severity (p=0.048), and current smokers were estimated to have mean CES-D scores 3.1 points higher than non-smokers (p=0.02). HIV-infected women were estimated to have mean GAD-7 scores that were 1.7 points higher than non-HIV-infected women (p=0.01), and women with moderate, severe, or extremely severe hot flash severity were estimated to have mean anxiety symptom scores that were 1.9 points higher than women who reported none or mild hot flash severity (p=0.02).

Table 4.

a. & 4b: Baseline Associations of Hot Flash Characteristics with Mood and Anxiety Symptoms

| a. Multivariable Associations Including Hot Flashes with Total CES-D Score in Perimenopausal HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected Women (n=66) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 = 0.32, P<0.0001 | β-estimate | 95% CI | P-value |

| HIV Infection (yes) | 3.0 | [0.5,5.6] | 0.02 |

| Moderate-Extremely Severe Hot Flashesa (yes) | 3.1 | [0.0,6.1] | 0.048 |

| Experienced Hot Flashes ≥ 8 days in past month (yes) | 0.2 | [−2.9,3.3] | 0.91 |

| Current Smoking (yes) | 3.1 | [0.6,5.6] | 0.02 |

| b. Multivariable Associations Including Hot Flashes with Total GAD-7 Score in Perimenopausal HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected Women (n=66) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 = 0.30, P=0.0002 | β-estimate | 95% CI | P-value |

| HIV Infection (yes) | 1.7 | [0.4,3.0] | 0.01 |

| Moderate-Extremely Severe Hot Flashesa (yes) | 1.9 | [0.3,3.5] | 0.02 |

| Experienced Hot Flashes ≥ 8 days in past month (yes) | −0.05 | [−1.7,1.6] | 0.96 |

| Current Smoking (yes) | 1.0 | [−0.3,2.3] | 0.13 |

Defined as a reported MRS item 1 score of 2, 3, or 4 (indicating moderate, severe, or extremely severe hot flashes).

Predictors of Affective Symptoms at Baseline in HIV-Infected Subgroup

In the univariable models for baseline GAD-7 scores among the HIV-infected women, a significant relationship was observed between duration of HIV and GAD-7 scores, with mean GAD scores decreasing by an estimated 3.9 points for women living 10 years longer with HIV (p=0.02). A significant association between GAD-7 scores and current antiretroviral therapy use was not observed, nor were significant univariable associations between duration of HIV or current antiretroviral therapy use and CES-D scores observed (p>0.05).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study represents the first longitudinal analysis reporting differences in affective and menopause symptoms between perimenopausal women with and without HIV of similar race, body mass index, menstrual patterns, and age. Our findings demonstrate that HIV-infected women, with relatively stable HIV-infection, have greater depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to non-HIV-infected women, and these symptom levels remain significantly elevated compared to non-HIV-infected women after one-year of follow-up. Significant differences in symptom scores between or within each group over the 12-month period were not observed in our cohort. The between-group differences in mood and anxiety symptoms at baseline remained significant when controlling for factors that differed between the groups including smoking status, substance abuse history, and antidepressant use. Furthermore, an association of hot flash severity and both depression and anxiety scores was observed. Collectively, these findings illustrate that HIV-infected women experience a disproportionate burden of affective symptoms at midlife, which persist during the perimenopause transition. Such symptoms, particularly depression and anxiety, have important clinical implications for the growing number of women aging with HIV, because of their impact on quality of life, HIV treatment adherence, and resulting mortality3,22,23.

Depression is the most robust predictor of non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy24, and has also been implicated in failure to be retained in HIV care25. Failure to maintain viral load suppression is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, as well as increased risk of HIV transmission26. However, effective depression interventions exist, some of which directly target adherence to antiretroviral therapy27. Our findings highlight the need for careful assessment of depressive symptoms in HIV-infected women during perimenopause, when the risk for depressive symptoms is elevated, particularly among those with a known history of depression.

The overall estimated prevalence of current depression based on the established CES-D threshold score in both groups of our study cohort exceeds the national average of 12.3% for women age 40–59 years28, and is notably greater than previous reports of 19.4%4 and 25.8%3 among women living with HIV in their mid-to-late thirties (i.e., younger than average age of perimenopause). The proposed relationship between HIV and depression in our sample of perimenopausal women is unlikely due to age alone, as depressive symptoms tend to remain stable or decline with increasing age in both the general population and in HIV-infected populations29. At least among the women living with HIV, this may be an artifact of the increased stressors known to impact persons living with HIV, such as poverty, unstable housing, and abuse histories. Further, the influence of HIV disease burden notwas unlikely to have influenced CES-D scores, as 77% of the HIV-infected women had stable HIV infection, indicated by undetectable HIV viral load levels. Based on our findings, a greater hot flash burden and other psychosocial factors associated with midlife and the perimenopause may also result in more psychological distress.

Our observed association between hot flashes and depressive symptoms is similar to findings from Maki and colleagues5 who determined that vasomotor symptoms predicted elevated depressive symptoms in both HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected women. Our HIV-infected women reported greater hot flash severity compared to the non-HIV-infected women at both baseline and at 12 months. This finding suggests that hot flash severity may serve as a sex-specific contributor to depressive symptoms among HIV-infected women during the menopause transition. As such, assessment and treatment of hot flashes among HIV-infected women at midlife is encouraged to reduce this burdensome symptom and its potential influence on depressive symptoms in this population.

It is notable that the prevalence of depressive symptoms in the sample was elevated despite the fact that nearly half of the HIV-infected women reported current use of antidepressant medications. While antidepressant dosing information was not determined, this observation suggests that HIV-infected women may be sub-optimally treated for their depressive symptoms, consistent with a report by Mello et al. (2010)3, who found that only 23% of currently depressed, HIV-infected women were receiving antidepressants. This may reflect a lack of or ineffective depression screening practices in the places where HIV-infected women seek care, or reduced adherence to psychiatric medications. A more recent study documented disparities in antidepressant treatment among individuals living with HIV by gender; while women with HIV are more likely than HIV-infected men to receive antidepressant treatment, they demonstrate substantial drop-off along the depression treatment cascade, which may result in suboptimal treatment30. Establishing effective means by which to identify and treat depression in the settings in which older, HIV-infected women are likely to seek health care is critical to optimize overall quality of life and to support adherence to life-saving antiretroviral therapy.

HIV-infected participants in the present study also reported worse anxiety symptoms than women without HIV, both at baseline and one year, though the clinical relevance of these between-group differences (e.g., the difference between mild to minimal anxiety symptoms) is less clear as anxiety symptoms were in the mild range among the HIV-infected group. Anxiety disorders are prevalent among HIV-infected individuals, with studies utilizing structured interviews documenting rates of approximately 11–12%4,31. Low rates of anxiety in the sample may be explained by the anxiety scale used, which reflects symptoms specific to generalized anxiety, and thus may have failed to capture the full range of symptoms characterizing the broader group of recognized anxiety symptoms pertinent to this population. A significant relationship between length of time living with HIV (mean duration of HIV in this cohort was 14±6 years) and anxiety was also observed, such that women living with HIV for longer periods of time reported lower levels of anxiety. Existing qualitative data suggests this may be a result of increased mastery of managing an HIV diagnosis, as well as decreased worry about immediate survival32. Thus, assessment of anxiety symptoms among women newly diagnosed with HIV at midlife, during perimenopause, may be critical given the potential for the cumulative effects of hormonal changes and a new HIV diagnosis on anxiety symptom burden.

Smoking has been associated with depression in HIV-infected individuals33. In the current study, smoking, in addition to HIV-infection and hot flash severity, was independently associated with depressive symptoms. Furthermore, among non-HIV-infected women, current or past smoking has been frequently associated with presence and severity of hot flashes, as well as hot flash severity21. Seventy percent of the HIV-infected women were smokers in our study, which is consistent with previous literature documenting increased smoking rates among HIV-infected individuals compared with non-HIV-infected individuals34–37. Similarly, substance abuse is common among individuals with HIV38, and 76% of the HIV-infected women in our cohort reported a history of substance abuse. Substance abuse history has been linked to nonuse of antiretroviral medications39. Together with depressive symptoms, a history of substance abuse makes this population of women particularly at risk for adverse outcomes. Indeed, providing education on the deleterious effects of cigarette smoking and substance abuse on physical and mental health to women at midlife is an important strategy to improve wellness in this population.

Although the longitudinal nature of this investigation and study cohort enhanced the validity of the study findings, generalizability may be limited due to the small sample size. Further, this was a clinical population with pre-specified eligibility criteria versus a community-based epidemiology study, thus, study findings may be limited by selection bias. Missing data existed for some of the HIV clinical variables including HIV viral load and CD4 count due to poor venous access, which limited blood collection. Thus, models assessing the relationship between HIV-specific clinical variables and mood symptoms could not be fully evaluated. Data on “current” substance abuse were not collected. Thus, the relationship between current substance abuse and hot flashes could not be evaluated in the multivariable models. Findings from this current study of perimenopausal women with HIV support further evaluation of the association between markers of immune function and degree of HIV viral suppression and vasomotor symptoms, as well as the degree of anxiety and depressive symptoms in larger studies of HIV-infected women in the perimenopause and postmenopausal phase.

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate that perimenopausal HIV-infected women experience a disproportionate rate of affective symptom burden, particularly depressive symptoms, compared to non-HIV-infected women during 12 months of follow up. Furthermore, we found that vasomotor symptoms, specifically hot flash severity which was increased in HIV-infected women compared to non-HIV-infected women, were also associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms in our cohort. The simultaneous occurrence of increased vasomotor and affective symptoms among HIV-infected women at midlife has potential to further compromise a variety of social and clinical factors including quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. For this reason, it is imperative for clinicians caring for HIV-infected women in the perimenopause transition, to assess for new onset, persistent, or increased presence of mood symptoms or anxiety, and consider initiating or adjusting current treatment regimens for affective symptoms, to prevent negative implications on the overall health and wellbeing of this population. To this end, traditional barriers to psychological screening, including diffusion of responsibility among clinicians, uncertainly about how to manage elevated scores on screening instruments, and lack of referral sources, need to be addressed, and systems put in place to support clinicians in their effort to provide comprehensive care to the growing number of HIV-infected women at midlife.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to the nurses, bionutritionists, and staff of the Clinical Research Center at MGH for their assistance with our study. We would also like to thank our dedicated study participants.

Source of Funding: Funding for this project was provided by NIH K23 NR011833-01A1 to Dr. Looby. The project described was also supported by Grant Number 8 UL1 TR000170-05 and 1 UL1 RR025758-04, Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, and the Harvard Nutrition and Obesity Research Center DK040561. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources, the National Center for Advancing Translational Science or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Looby has the following active funding: NIAID: 1R01AI123001-01 (partially supported Dr. Looby’s time on this manuscript), The Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award (MGH Executive Committee on Research), Connell Extension Grant (William F. Connell family and the Yvonne L. Munn Center for Nursing Research). Dr. Psaros has the following active funding: NIMH K23MH096651-05 (partially supported Dr. Psaros’ time on this manuscript), NIMH R01MH112385, The Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award (MGH Executive Committee on Research), and NCCIH R34AT009170. Dr. Raggio does not currently have any active research support to report. Laura Smeaton reports this publication was made possible with help from the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI060354), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NIGMS, NIMHD, FIC, and OAR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Unrelated to this project, Dr. Joffe reports the following funding from the NIH: 1R01AG053838, Merck, and SAGE.

Unrelated to this project, Dr. Looby is a non-paid Board member of the community non-profit organization Healing Our Community Collaborative, and received one-time compensation for CME educational offerings sponsored by the Physicians Research Network (NY,NY, 2016) and Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center (NH, 2017). Dr. Psaros has been a consultant to Bracket Global (unrelated to this project, completed 2015). Dr. Shifren serves as a research consultant for the New England Research Institutes. Unrelated to this manuscript, Dr. Grinspoon served as a consultant to Theratechnologies and received research funding from Gilead, KOWA and Theratechnologies. Dr. Joffe reports receiving research funding from Merck and SAGE, and consulting for the following companies, unrelated to this project: NeRRe, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Merck, and SAGE.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Financial Disclosures: For the remaining authors, no potential conflicts of interest were declared.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT01142817

Disclaimer: Some of these data were presented in posters at the annual meeting for the North American Menopause Society in 2013 and 2014. Baseline data pertaining to demographic, clinical data, and hot flashes, previously published in Looby SE, Shifren J, Corless I, et al. Increased hot flash severity and related interference in perimenopausal human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Menopause. Apr 2014;21(4):403–409, were included in this manuscript for 12 month comparison.

References

- 1.Kaiser KFF. [Accessed May 18, 2017];Women and HIV/AIDS in the United States. 2014 http://kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/women-and-hivaids-in-the-united-states/

- 2.Ivanova EL, Hart TA, Wagner AC, Aljassem K, Loutfy MR. Correlates of anxiety in women living with HIV of reproductive age. AIDS Behav. 2012 Nov;16(8):2181–2191. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mello VA, Segurado AA, Malbergier A. Depression in women living with HIV: clinical and psychosocial correlates. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010 Jun;13(3):193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Ten Have T, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 May;159(5):789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maki PM, Rubin LH, Cohen M, et al. Depressive symptoms are increased in the early perimenopausal stage in ethnically diverse human immunodeficiency virus-infected and human immunodeficiency virus-uninfected women. Menopause. 2012 Nov;19(11):1215–1223. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318255434d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, Harlow BL. Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition: the Harvard study of moods and cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Apr;63(4):385–390. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Youk A, Schott LL, Joffe H. Patterns of depressive disorders across 13 years and their determinants among midlife women: SWAN mental health study. J Affect Disord. 2016 Dec;206:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Liu L, Gracia CR, Nelson DB, Hollander L. Hormones and menopausal status as predictors of depression in women in transition to menopause. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Jan;61(1):62–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang Y, et al. Does risk for anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of women's health across the nation. Menopause. 2013 May;20(5):488–495. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182730599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soares CN. Depression and Menopause: Current Knowledge and Clinical Recommendations for a Critical Window. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun;40(2):239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frey BN, Lord C, Soares CN. Depression during menopausal transition: a review of treatment strategies and pathophysiological correlates. Menopause Int. 2008 Sep;14(3):123–128. doi: 10.1258/mi.2008.008019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joffe H, Crawford SL, Freeman MP, et al. Independent Contributions of Nocturnal Hot Flashes and Sleep Disturbance to Depression in Estrogen-Deprived Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Oct;101(10):3847–3855. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Looby SE, Shifren J, Corless I, et al. Increased hot flash severity and related interference in perimenopausal human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Menopause. 2014 Apr;21(4):403–409. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31829d4c4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Apr;97(4):1159–1168. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-reportdepression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997 Jun;12(2):277–287. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006 May 22;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ZEG. [Accessed October, 2012];MRS-The menopause rating scale: The Berlin Center for Epidemiology and Health Research [website] 2008 http://www.menopause-rating-scale.info/

- 19.Heinemann K, Ruebig A, Potthoff P, et al. The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) scale: a methodological review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004 Sep 02;2:45. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpenter JS. The Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale: a tool for assessing the impact of hot flashes on quality of life following breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001 Dec;22(6):979–989. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallicchio L, Miller SR, Kiefer J, Greene T, Zacur HA, Flaws JA. Risk factors for hot flashes among women undergoing the menopausal transition: baseline results from the Midlife Women's Health Study. Menopause. 2015 Oct;22(10):1098–1107. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kacanek D, Jacobson DL, Spiegelman D, Wanke C, Isaac R, Wilson IB. Incident depression symptoms are associated with poorer HAART adherence: a longitudinal analysis from the Nutrition for Healthy Living study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Feb;53(2):266–272. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b720e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kremer H, Sonnenberg-Schwan U, Arendt G, et al. HIV or HIV-therapy? Causal attributions of symptoms and their impact on treatment decisions among women and men with HIV. Eur J Med Res. 2009 Apr 16;14(4):139–146. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-4-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Oct 01;58(2):181–187. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuniga JA, Yoo-Jeong M, Dai T, Guo Y, Waldrop-Valverde D. The Role of Depression in Retention in Care for Persons Living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016 Jan;30(1):34–38. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 01;375(9):830–839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bianco JA, Heckman TG, Sutton M, Watakakosol R, Lovejoy T. Predicting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected older adults: the moderating role of gender. AIDS Behav. 2011 Oct;15(7):1437–1446. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9756-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression in the U.S. household population, 2009–2012. NCHS Data Brief. Dec;2014(172):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabkin JG. HIV and depression: 2008 review and update. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008 Nov;5(4):163–171. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bengtson AM, Pence BW, Crane HM, et al. Disparities in Depressive Symptoms and Antidepressant Treatment by Gender and Race/Ethnicity among People Living with HIV in the United States. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sewell MC, Goggin KJ, Rabkin JG, Ferrando SJ, McElhiney MC, Evans S. Anxiety syndromes and symptoms among men with AIDS: a longitudinal controlled study. Psychosomatics. 2000 Jul-Aug;41(4):294–300. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Psaros C, Barinas J, Robbins GK, Bedoya CA, Park ER, Safren SA. Reflections on living with HIV over time: exploring the perspective of HIV-infected women over 50. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(2):121–128. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.917608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart DW, Jones GN, Minor KS. Smoking, depression, and gender in low-income African Americans with HIV/AIDS. Behav Med. 2011 Jul;37(3):77–80. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2011.583946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CDC. [Accessed March 17th, 2017];Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. 2015 https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/

- 35.Reynolds NR. Cigarette smoking and HIV: more evidence for action. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009 Jun;21(3 Suppl):106–121. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shuter J, Bernstein SL. Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of nonadherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008 Apr;10(4):731–736. doi: 10.1080/14622200801908190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tesoriero JM, Gieryic SM, Carrascal A, Lavigne HE. Smoking among HIV positive New Yorkers: prevalence, frequency, and opportunities for cessation. AIDS Behav. 2010 Aug;14(4):824–835. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durvasula R, Miller TR. Substance abuse treatment in persons with HIV/AIDS: challenges in managing triple diagnosis. Behav Med. 2014;40(2):43–52. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2013.866540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen MH, Cook JA, Grey D, et al. Medically eligible women who do not use HAART: the importance of abuse, drug use, and race. Am J Public Health. 2004 Jul;94(7):1147–1151. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]