Summary

Introduction

Prior studies of outcomes following genitoplasty report high rates of surgical complications among children with atypical genitalia. Few studies have prospectively assessed outcomes after contemporary surgical approaches.

Objective

We report the occurrence of early postoperative complications and of cosmetic outcomes (as rated by surgeons and parents) at 12 months following contemporary genitoplasty procedures in children born with atypical genitalia.

Study design

This 11-site, prospective study included children ≤ 2 years of age, with Prader 3-5 or Quigley 3-6 external genitalia, with no prior genitoplasty and non-urogenital malformations at the time of enrollment. Genital appearance was rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Paired t-tests evaluated differences in cosmesis ratings.

Results

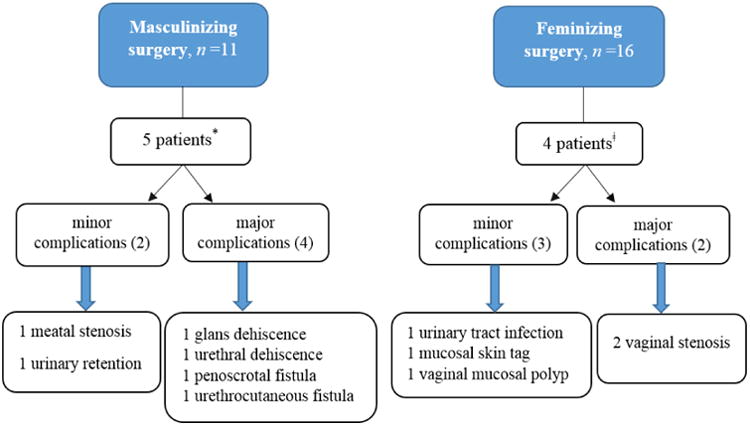

Out of 27 children, 10 were 46,XY patients with the following diagnoses: gonadal dysgenesis, partial androgen insensitivity syndrome or testosterone biosynthetic defect, severe hypospadias and microphallus, who were reared male. Sixteen 46,XX CAH patients were reared female and one child with sex chromosome mosaicism was reared male. Eleven children had masculinizing genitoplasty for penoscrotal or perineal hypospadias (one-stage, three; two-stage, eight). Among one-stage surgeries, one child had meatal stenosis (minor) and one developed both urinary retention (minor) and urethrocutaneous fistula (major) (Summary Fig.). Among two-stage surgeries, three children developed a major complication: penoscrotal fistula, glans dehiscence or urethral dehiscence. Among 16 children who had feminizing genitoplasty, vaginoplasty was performed in all, clitoroplasty in nine, external genitoplasty in 13, urethroplasty in four, perineoplasty in five and total urogenital sinus mobilization in two. Two children had minor complications: one had a UTI and one had both a mucosal skin tag and vaginal mucosal polyp. Two additional children developed a major complication: vaginal stenosis. Cosmesis scores revealed sustained improvements from 6 months post-genitoplasty as previously reported, with all scores good or satisfied.

Discussion

In these preliminary data from a multi-site, observational study, parents and surgeons were equally satisfied with the cosmetic outcomes 12 months after genitoplasty. A small number of patients had major complications, in both feminizing and masculinizing surgeries; two-stage hypospadias repair had the most major complications. Long-term follow-up of patients at post-puberty will provide a better assessment of outcomes in this population.

Conclusion

In this cohort of children with moderate-to-severe atypical genitalia, we present preliminary data on both surgical and cosmetic outcomes. Findings from this study, and from following these children in long-term studies, will help guide practitioners in their discussions with families about surgical management.

Keywords: Disorders of sex development, Congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Genitoplasty

Introduction

One in 1000 babies is born with some degree of genital atypia [1]. There are few published outcomes related to cosmesis and postoperative complications following reconstructive surgery in children with atypical genitalia. Historical studies have reported a wide range of outcomes and relied on physician cosmetic ratings [2-7]. Importantly, with the advent of more modern surgical techniques and specialized centers focused on the management of children with atypical genitalia, prospective studies analyzing early outcomes allow for better understanding of morbidities associated with contemporary genitoplasty procedures.

Children with atypical genitalia who may undergo masculinizing or feminizing surgeries include those identified as having congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), penoscrotal or perineal hypospadias and microphallus, gonadal dysgenesis, androgen insensitivity syndrome, and presentations of 46, XY disorders of sex development (DSD). Most outcome studies on hypospadias have focused on less severe cases, with urethral meatus located from the distal to proximal shaft. This current study included only the most severe forms of hypospadias.

Following penoscrotal or perineal hypospadias repair, children may have complications including post-void dribbling, urethral stricture, urinary tract infection, fistula, testicular pain, and urethral or meatal stenosis [7-10]. Following feminizing genitoplasty, children may require additional surgeries, secondary to vaginal stenosis or other complications including scarring, urethral stricture, urinary incontinence and urethrovaginal fistula [11-13].

The objective of the current study was to prospectively assess early surgical outcomes of contemporary genitoplasty procedures, and cosmetic outcomes 12 months after genitoplasty for children with moderate to severe atypical genitalia at 11 sites across the United States. The current paper reports the occurrence of early minor and major postoperative complications at 12 months post-genitoplasty in a cohort of children with the more severe forms of genital atypia. Cosmetic outcomes, as rated by both surgeons and parents, at 12 months post-genitoplasty are reported. It has previously been reported that surgeons and parents rated cosmetic outcomes as satisfactory or good 6 months after genitoplasty [14]. It was hypothesized that cosmetic outcomes would remain stable over the follow-up period for all raters.

Methods

Study design and enrollment

Beginning in 2013, participants were enrolled in a five-year, multi-center, prospective, observational study to evaluate cosmesis, frequency and types of surgery performed, and early postoperative outcomes in children with atypical genitalia. Eligible participants included families with children aged ≤2 years with moderate to severe atypical genitalia as defined by: a Prader 3-5 rating in a 46,XX child or a Quigley 3-6 rating in a child with a 46,XY or a 45,X/46,XY chromosomal complement, and with no prior genitoplasty. Patients with non-urogenital malformations were excluded. Families were eligible to participate whether they elected to have surgery or not. The types of procedures performed and clinical information collected have been previously reported [14]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site, and all parents/guardians provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The present study reported on families who chose for their child to have surgery and completed the 12 month postoperative visit.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Study data were collected on paper forms and then entered and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools at University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center [15]. For data analyses, the primary outcomes of interest were the incidence of early (<12 months) complications and cosmesis. Complications were defined as any problem that occurred during the study period. One patient was excluded from analysis because he only had a circumcision and had not yet undergone penile surgery. Paired t-tests evaluated differences between 6-month and 12-month mean cosmesis ratings (4-point Likert: 1=good, 2=satisfied, 3=dissatisfied and 4=very dissatisfied) for mothers, fathers and surgeons. Results corresponding to p-values <0.05 are described as significant. All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Twenty-seven children completed the 12 month postoperative visit; 27 mothers, 22 fathers and 13 surgeons provided cosmetic ratings. The mean age ± SD at the 12-month postoperative visit was 25±10 months. Ten (37%) 46,XY patients with the following diagnoses gonadal dysgenesis (two), partial androgen insensitivity syndrome or testosterone biosynthetic defect (one), or severe hypospadias and microphallus (seven) were reared male. Sixteen (59%) 46,XX, CAH patients were reared female. One child (4%) with sex chromosome mosaicism (45,X/46,XY) was reared male. Additional cohort characteristics are in Table 1.

Table 1. Cohort characteristics, n=27.

| Characteristics | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD (in months) at time of initial surgery | 13 ± 9 | ||

|

| |||

| Mean age ± SD (in months) at 12 month post-operative visit | 25 ± 10 | ||

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White/Caucasian | 19 (70) | ||

| Black/African American | 3 (11) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (4) | ||

| Other | 1 (4) | ||

| Declined to answer | 3 (11) | ||

|

| |||

| Annual Household Income | |||

| < $30,000 | 6 (22) | ||

| $30,000- $59,999 | 7 (26) | ||

| $60,000-89,999 | 4 (15) | ||

| ≥ $90,000 | 10 (37) | ||

|

| |||

| Type of surgery, by diagnosis | Feminizing surgery | Masculinizing surgery | |

|

|

|

||

| 1-stage | 2-stage | ||

| congenital adrenal hyperplasia | 16 | ||

| gonadal dysgenesis (partial or mixed) | 1 | 2 | |

| severe hypospadias/microphallus | 1 | 6 | |

| partial androgen insensitivity syndrome or testosterone biosynthetic defect | 1 | ||

Genitoplasty

Planned one-stage masculinizing procedures

Out of 27 children who had genitoplasty, 11 children received masculinizing genitoplasty for penoscrotal or perineal hypospadias. Three children had a planned one-stage repair procedure; of these one patient (33%) had a pre-operative Quigley score of 5 and two (67%) had a Quigley score of 3. The maneuver performed to straighten chordee was midline dorsal plication without mobilization of the neurovascular bundles. Children had a urethroplasty using the tubularized incised plate (TIP) technique and a further coverage layer using a dorsal pedicle flap. Additional genitoplasty techniques performed were: Byars flaps, complex scrotoplasty, simple scrotoplasty and reconstruction of penopubic/penoscrotal angles. Circumcision and degloving (as a maneuver to correct chordee) were part of all masculinizing surgeries. Two out of these three patients received pre-operative testosterone therapy (topical, one; intramuscular, one).

Planned two-stage masculinizing procedures

Eight children had a planned 2-stage hypospadias procedure of whom one patient (13%) had a pre-operative Quigley score of 5, one (13%) had a Quigley score of 4 and four (50%) had a Quigley score of 3. Among the eight planned two-stage masculinizing surgeries, the orthoplasty maneuvers performed to straighten chordee were: midline dorsal plication without mobilization of the neurovascular bundles, ventral corporal body grafting, distal division of urethral plate, and proximal division of urethral plate. The following techniques were employed for the first stage: transposition of skin flaps, tunica vaginalis and vascularized skin flaps, inlay graft and inlay flap. The following techniques were employed for the second stage: TIP, Thiersch-Duplay, tunica vaginalis flaps, inlay graft and inlay flap. Additional genitoplasty techniques performed on children were: Byars flaps, simple scrotoplasty, complex scrotoplasty, reconstruction of penopubic/penoscrotal angles, scrotal transposition and scrotal transposition correction. Five out of these eight patients received pre-operative testosterone therapy (topical, two; intramuscular, three).

Feminizing procedures

Among 16 children who had feminizing genitoplasty, vaginoplasty was performed in all, clitoroplasty in nine (56%), external genitoplasty in 13 (81%), urethroplasty in four (25%), perineoplasty in five (31%) and total urogenital sinus mobilization in two. Nine patients (56%) had a pre-operative Prader score of 3, five (31%) had a Prader score of 4 and two (13%) had a Prader score of 5. Children who underwent feminizing surgery received only their medically indicated hormonal therapy to manage their adrenal insufficiency and stress dose steroids during the peri-operative period.

Early postoperative complications

Masculinizing surgery

Out of the 11 masculinizing surgery patients, five developed early complications. Among one-stage surgeries, one child had meatal stenosis (minor) and one developed both urinary retention (minor) and urethrocutaneous fistula (major) (Table 2). Among two-stage surgeries, three children developed a major complication: penoscrotal fistula, glans dehiscence or urethral dehiscence (Table 2).

Table 2. Early postoperative complications following masculinizing surgeries.

| Diagnosis | Pre-op Quigley Score | Age range at initial surgery (in months) | Initial surgery | Complication(s) (major or minor) | Time complication was identified, months since first surgery | Consequence of Identification of Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed gonadal dysgenesis | Quigley 3 | 19-24 | Single stage: orthoplasty urethroplasty genitoplasty: BF, SS | urinary retention (minor) | 5 days | catheter placed |

| urethrocutaneous fistula (major) | 7 | timing of treatment to be determined | ||||

| Mixed gonadal dysgenesis | Quigley 4 | 7-12 | 2-stage reconstruction: orthoplasty 1st stage: Thiersch-Duplay and inlay flap, further coverage layer over urethroplasty (dorsal pedicle flap) genitoplasty: BF, SS, RPP 2nd stage: Thiersch-Duplay |

penoscrotal fistula (major) | 5 | fistula repair |

| XY DSD, unknown | Quigley 3 | 13-18 | 2-stage reconstruction: orthoplasty and proximal division of urethral plate genitoplasty: BF, SS left orchidopexy 1st stage: TIP 2nd stage: Thiersch-Duplay, TIP right orchidopexy |

glans dehiscence (major) | 7 | Revision distal hypospadias repair |

| XY DSD, unknown | Quigley 3 | 0-6 | 2-stage reconstruction: orthoplasty and distal division of urethral plate 1st stage: inlay flap genitoplasty: CS, RPP, scrotal transposition correction orchidopexy 2nd stage: TIP and inlay flap |

urethral dehiscence/ wound adhesion (major) | 6 | timing of treatment to be determined |

| XY DSD unknown | Quigley 3 | 7-12 | Single stage: orthoplasty urethroplasty genitoplasty: BF, SS | meatal stenosis (minor) | < 4 | surgery |

orthoplasty maneuver to straighten ventral chordee = midline dorsal plication without mobilization of neurovascular bundles

TIP = tubularized incised plate

genitoplasty: BF = Byars flaps, CS = complex scrotoplasty, SS = simple scrotoplasty, RPP = reconstruction of penopubic/penoscrotal angles

urethroplasty: TIP and further coverage layer over urethroplasty (dorsal pedicle flap)

Feminizing surgery

Among the 16 feminizing surgery patients, none exhibited ischemic tissue loss, wound separation, wound infection or significant bleeding. Two children had minor complications: one had a UTI and one had both a mucosal skin tag and vaginal mucosal polyp. Two additional children developed a major complication: vaginal stenosis (Table 3).

Table 3. Early postoperative complications following feminizing surgeries.

| Diagnosis | Pre-op Prader Score | Age range at initial surgery (in months) | Initial surgery | Complication(s) (major or minor) | Time complication was identified, months since first surgery | Consequence of Identification of Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAH | Prader 5 | 13-18 | clitoroplasty, vaginoplasty with anterior sagittal transrectal approach/pull through, labioplasty, urogenital sinus mobilization | vaginal stenosis (major) | 2 | treatment to be determined |

| CAH | Prader 4 | 7-12 | clitoroplasty, vaginoplasty with TUM, labioplasty | mucosal skin tag (minor) | 2 | excised skin tag |

| vaginal mucosal polyp (13 × 3mm) (minor) | 10 | excised polyp | ||||

| CAH | Prader 3 | 7-12 | clitoroplasty, vaginoplasty with TUM and flap | urinary tract infection (minor) | 2 | antibiotic |

| CAH | Prader 3 | 7-12 | clitoroplasty, vaginoplasty with flap, labioplasty | vaginal stenosis and labial fusion (major) | < 6 | redo-vaginoplasty and bilateral labioplasty of the labia minora |

TUM = total urogenital mobilization

Cosmetic ratings

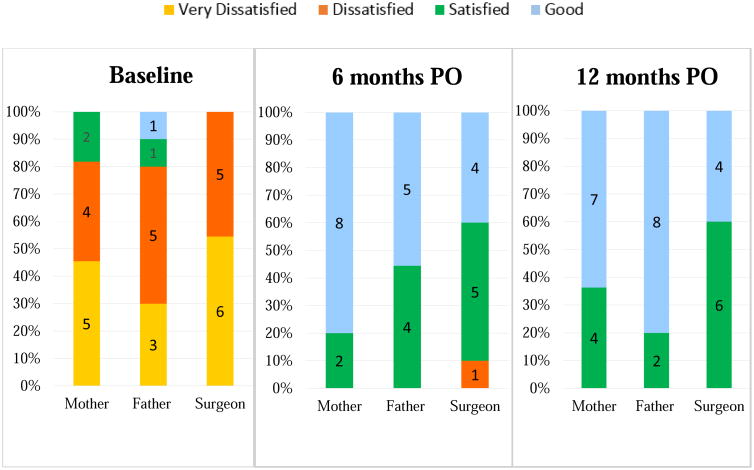

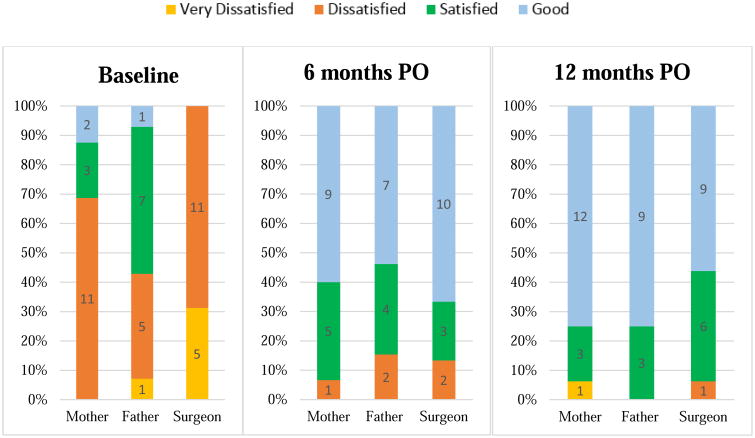

(based on Likert scale: 1=good, 2=satisfied, 3=dissatisfied, 4=very dissatisfied). Following planned one and two-stage masculinizing surgeries, mean cosmesis scores (all scores) from parents and surgeons were good or satisfied at 12 month post operation (one-stage: mothers, 1.3±0.6; fathers, 1.0±0.0; surgeons, 2.0±0.0. two-stage: mothers, 1.4±0.5; fathers, 1.3±0.5; surgeons, 1.4±0.5). Following feminizing surgeries, all means scores from surgeons and parents were good at 12 month post operation (mothers, 1.3±0.4; fathers, 1.3±0.5; surgeons, 1.4±0.5). In the current cohort, cosmesis scores significantly improved from before surgery, as previously reported [14]. Overall, cosmetic improvements observed at 6 months were sustained at 12 months post-genitoplasty (Fig. 1a, 1b).

Figure 1.

a. Cosmesis scores in patients (n=11) who underwent masculinizing surgery. Cosmesis was rated by mothers, fathers and surgeons.

b. Cosmesis scores in patients (n=16) who underwent feminizing surgery. Cosmesis was rated by mothers, fathers and surgeons.

number=frequency, PO= postoperative

Discussion

This study reports the first NIH-funded, multi-institutional collaboration studying early surgical and cosmetic outcomes following contemporary genitoplasty procedures in children with moderate to severe atypical genitalia. This report included 27 children followed prospectively 12 months after genitoplasty at 11 centers in the United States. Among patients who had masculinizing surgery, two children had a minor complication and four children developed a major complication. Among patients who had feminizing surgery, two children had minor complications and two additional children developed a major complication. These preliminary findings warrant further long-term patient follow-up at post puberty to evaluate long-term complications. This study also showed that cosmesis scores, which had significantly improved from before surgery to 6 months after surgery, were sustained at 12 months post genitoplasty.

Previous studies on feminizing genitoplasty have been limited because of significant heterogeneity in cohorts (i.e. included patients with prior surgeries) [16, 17], retrospective design [18-23] and single-center or single surgeon series [11, 13, 24-26]. Importantly, assessment of early surgical complications have been limited by studies with short follow-up periods following genitoplasty [18, 24, 27-29]. Similarly, previous studies on hypospadias repairs have lacked objective measures and are limited by short-term follow-up [30-32]. Studies reporting surgical outcomes following hypospadias repair had median follow-up periods of <4 years after surgery [22, 25, 26, 33]. Many complications such as urethral diverticulum, urethral stenosis or recurrent chordee can appear after many years of follow up [30].

Strengths of this study include the prospective and multi-center design at 11 centers that provide care throughout the United States. This study focused on the repair of more complex genital atypia. Thus, this study will help us better evaluate surgical outcomes in these complex cases. Additionally, due to the prospective design of the current investigation, data were collected on all genitoplasty complications, including those that require additional surgery (i.e. vaginal stenosis, urethral stenosis and fistula) as well as those that do not.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size; therefore, findings should be interpreted with caution and may be not be generalizable to all children undergoing genitoplasty. This present evaluation is limited by its short-term follow-up of genitoplasty. Long-term follow-up and post-pubertal evaluation will provide a better overall assessment. This study excluded children with non-urogenital malformations; thus, it is unknown if complication rates differ for more medically complex children. In addition, limitations associated with multisite studies also include variations in surgical technique, postoperative management and surgeon experience.

Conclusions

This prospective, multi-center study, represents the start of an important, long-term process of better determining outcomes of contemporary genitoplasty procedures in children with moderate to severe atypical genitalia. Further long-term follow-up will provide a more comprehensive view of patient outcomes in this population. Parents and physicians report overall satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes for children. Findings from this study, and from following these children in long-term studies, will help guide practitioners in their discussions with families about surgical management.

Summary Fig. Surgical complications at 12 month postoperative follow-up, n=27.

*Among the 6 complications in the masculinizing surgery group, one patient developed both urinary retention (minor) and urethrocutaneous fistula (major).

ǂAmong the 5 complications in the feminizing surgery group, one patient had both a mucosal skin tag (minor) and vaginal mucosal polyp (minor).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the parents and children who participated in this study. All phases of this study were supported by an NIH grant, R01HD074579, under the direction of primary investigators Dr. Amy B. Wisniewski and Dr. Larry L. Mullins. Dr. Natalie J. Nokoff is supported by a T32 grant (T32 DK 63687).

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Paul Austin serves on the pediatric advisory group and is a clinical investigator for Allergan. Dr. Dix Poppas is the co-founder of Promethean Surgical Devices, Inc. and serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of the CARES Foundation. Dr. Chan Yee-Ming serves on the Scientific Advisory Board for Abbvie. None are directly related to the funding or design of the study.

Footnotes

Ethics approval: The local institutional review boards at all sites approved this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Blackless M, Charuvastra A, Derryck A, Fausto-Sterling A, Lauzanne K, Lee E. How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis. Am J Human Biol. 2000;12(2):151–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(200003/04)12:2<151::AID-AJHB1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta DK, Shilpa S, Amini AC, Gupta M, Aggarwal G, Deepika G, et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia: long-term evaluation of feminizing genitoplasty and psychosocial aspects. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22(11):905–9. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1765-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stikkelbroeck NM, Beerendonk CC, Willemsen WN, Schreuders-Bais CA, Feitz WF, Rieu PN, et al. The long term outcome of feminizing genital surgery for congenital adrenal hyperplasia: anatomical, functional and cosmetic outcomes, psychosexual development, and satisfaction in adult female patients. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2003;16(5):289–96. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(03)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tourchi A, Hoebeke P. Long-term outcome of male genital reconstruction in childhood. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9(6 Pt B):980–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rynja SP, de Jong TP, Bosch JL, de Kort LM. Functional, cosmetic and psychosexual results in adult men who underwent hypospadias correction in childhood. J Pediatr Urol. 2011;7(5):504–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krege S, Walz KH, Hauffa BP, Korner I, Rubben H. Long-term follow-up of female patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia from 21-hydroxylase deficiency, with special emphasis on the results of vaginoplasty. BJU Int. 2000;86(3):253–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00789.x. discussion 8-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sircili MH, Queiroz Silva FA, Costa EM, Brito VN, Arnhold IJ, Denes FT, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of masculinizing genitoplasty in large cohort of patients with disorders of sex development. J Urol. 2010;184(3):1122–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam PN, Greenfield SP, Williot P. 2-stage repair in infancy for severe hypospadias with chordee: long-term results after puberty. J Urol. 2005;174(4 Pt 2):1567–72. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000179395.99944.48. discussion 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spinoit AF, Poelaert F, Van Praet C, Groen LA, Van Laecke E, Hoebeke P. Grade of hypospadias is the only factor predicting for re-intervention after primary hypospadias repair: A multivariate analysis from a cohort of 474 patients. J Pediatr Urol. 2015;11(2):70.e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Migeon CJ, Wisniewski AB, Gearhart JP, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Rock JA, Brown TR, et al. Ambiguous Genitalia With Perineoscrotal Hypospadias in 46,XY Individuals: Long-Term Medical, Surgical, and Psychosexual Outcome. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):e31–e. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park S, Ha SH, Kim KS. Long-term Follow-up after Feminizing Genital Reconstruction in Patients with Ambiguous Genitalia and High Vaginal Confluence. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26(3):399–403. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailez MM, Gearhart JP, Migeon C, Rock J. Vaginal reconstruction after initial construction of the external genitalia in girls with salt-wasting adrenal hyperplasia. J Urol. 1992;148(2 Pt 2):680–2. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36691-0. discussion 3-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dangle P, Lee A, Chaudhry R, Schneck FX. Surgical Complications Following Early Genitourinary Reconstructive Surgery for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia- Interim Analysis at 6 Years. Urology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nokoff NJ, Palmer B, Mullins AJ, Aston CE, Austin P, Baskin L, et al. Prospective assessment of cosmesis before and after genital surgery. J Pediatr Urol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul A, Harris RT, Thielke Robert, Payne Jonathon, Gonzalez Nathaniel, Conde Jose G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lesma A, Bocciardi A, Montorsi F, Rigatti P. Passerini-glazel feminizing genitoplasty: modifications in 17 years of experience with 82 cases. Eur Urol. 2007;52(6):1638–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bocciardi A, Lesma A, Montorsi F, Rigatti P. Passerini-Glazel Feminizing Genitoplasty: A Long-term Followup Study. J Urol. 2005;174(1):284–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161211.40944.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salle JL, Lorenzo AJ, Jesus LE, Leslie B, AlSaid A, Macedo FN, et al. Surgical treatment of high urogenital sinuses using the anterior sagittal transrectal approach: a useful strategy to optimize exposure and outcomes. J Urol. 2012;187(3):1024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Bassam A, Gado A. Feminizing genital reconstruction: experience with 52 cases of ambiguous genitalia. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14(3):172–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sircili MH, de Mendonca BB, Denes FT, Madureira G, Bachega TA, e Silva FA. Anatomical and functional outcomes of feminizing genitoplasty for ambiguous genitalia in patients with virilizing congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 2006;61(3):209–14. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322006000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Pan J, Ji H, Wang Y, Shen W, Liu L, et al. Long-term evaluation of patients undergoing genitoplasty due to disorders of sex development: results from a 14-year follow-up. Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:298015. doi: 10.1155/2013/298015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faure A, Bouty A, Nyo YL, O'Brien M, Heloury Y. Two-stage graft urethroplasty for proximal and complicated hypospadias in children: A retrospective study. J Pediatr Urol. 2016;12(5):286.e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cambareri GM, Yap M, Kaplan GW. Hypospadias repair with onlay preputial graft: a 25-year experience with long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2016;118(3):451–7. doi: 10.1111/bju.13419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braga LH, Silva IN, Tatsuo ES. Total urogenital sinus mobilization in the repair of ambiguous genitalia in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2005;49(6):908–15. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302005000600009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garnier S, Maillet O, Cereda B, Ollivier M, Jeandel C, Broussous S, et al. Late surgical correction of hypospadias increases the risk of complications: a 501 consecutive patients series. BJU Int. 2017 Jan 13; doi: 10.1111/bju.13771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long CJ, Chu DI, Tenney RW, Morris AR, Weiss DA, Shukla AR, et al. Intermediate-Term Followup of Proximal Hypospadias Repair Reveals High Complication Rate. J Urol. 197(3):852–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Tatsuo ES, Silva IN, Pippi Salle JL. Prospective evaluation of feminizing genitoplasty using partial urogenital sinus mobilization for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Urol. 2006;176(5):2199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rink RC, Pope JC, Kropp BP, Smith ER, Keating MA, Jr, Adams MC. Reconstruction of the High Urogenital Sinus: Early Perineal Prone Approach Without Division of the Rectum. J Urol. 1997;158(3):1293–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farkas A, Chertin B, Hadas-Halpren I. 1-Stage Feminizing Genitoplasty: 8 years of experience with 49 cases. J Urol. 165(6):2341–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66199-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Win G, Cuckow P, Hoebeke P, Wood D. Long-term outcomes of pediatric hypospadias and surgical intervention. Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2012;3:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamond DA, Chan IHY, Holland AJA, Kurtz MP, Nelson C, Estrada CR, Jr, et al. Advances in paediatric urology. Lancet (London, England) 2017;390(10099):1061–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gong EM, Cheng EY. Current challenges with proximal hypospadias: We have a long way to go. J Pediatr Urol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNamara ER, Schaeffer AJ, Logvinenko T, Seager C, Rosoklija I, Nelson CP, et al. Management of Proximal Hypospadias with 2-Stage Repair: 20-Year Experience. J Urol. 2015;194(4):1080–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.04.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]