Abstract

The retrospectively investigation compared the efficacy and safety of Bortezomib (Btz) administration via subcutaneous (SC) and intravenous (IV) in 307 newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients from a single Chinese center. SC Btz is associated with better tolerance. However, IV administration achieves a faster and deeper response in these patients.

Background

Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is an important toxicity that limits the use of Bortezomib (Btz). Attempts to reduce PN have included its subcutaneous (SC) administration.

Patients and methods

Here we retrospectively analyzed 307 newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients from a single Chinese center, receiving Btz-based regimens administered either via SC injection (SC group, n=167) or IV infusion (IV group, n=140). The efficacy and safety of Btz administration via SC and IV were then compared.

Results

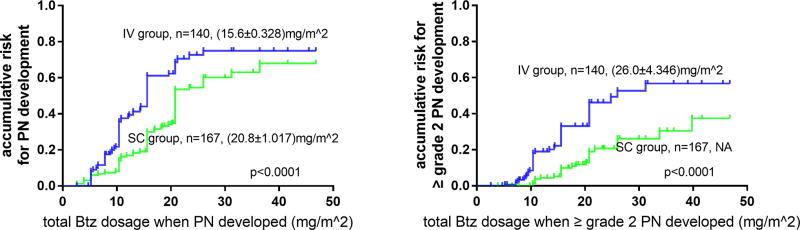

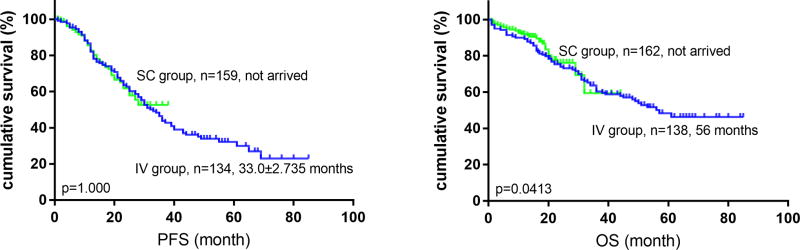

Most baseline characteristics were similar between these 2 groups. A lower frequency of adverse events (AEs), especially grade ≥3 peripheral neuropathy (PN) (p=0.002), was observed in SC compared to IV group. The estimated median Btz dosage when PN developed was higher (20.8 mg/m2 vs 15.6 mg/m2) and fewer patients reduced or discontinued Btz due to AEs in SC compared to IV group. The overall response rate (≥PR) was comparable (94.8% vs 96.2%). However, patients in IV group required fewer cycles to achieve partial response (PR) while larger proportion of patients in IV group achieved ≥VGPR. After a median follow-up of 23 (1–84) months, no significant difference in median progression-free survival (not arrived vs 33.0±2.735 months) and overall survival (not arrived vs 56.0 months) was noted.

Conclusion

SC Btz is associated with better tolerance; however, IV administration achieves a faster and deeper response in Chinese NDMM patients.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, bortezomib, subcutaneous, intravenous

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable plasma cell malignancy primarily affecting the elderly. The variety of clinical signs and symptoms profoundly impact the lives of patients and imposes a heavy burden on society. However, recent basic and clinical research developments have led to the use of novel therapeutic agents which have greatly improved overall survival (OS) and shifted treatment paradigms in MM.

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Btz) is a potent agent used extensively in the treatment of both newly diagnosed and relapsed MM, and as part of induction, consolidation, conditioning and maintenance therapies1–8. The standard administration route for Btz is intravenous (IV), but IV poses a therapeutic challenge in patients who have poor venous access. IV Btz administration is also limited by Btz-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN), which significantly impacts patients’ quality of life9. In 2008, a French group reported the results of a randomized phase I study (CAN-1004) that compared the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of IV versus subcutaneous (SC) administration of Btz in relapsed or refractory MM (RRMM) patients. This study also assessed the safety and efficacy of these two administration routes. The plasma concentration of Btz and the percent inhibition of 20S proteasome were measured on day 1 and 11 of cycle 1. Btz systemic exposure was equivalent with SC versus IV which led to similar overall 20S inhibition in both arms. The safety profile and response rate of SC did not appear inferior to IV, and the local tolerance of SC injection was also good. Based on these exploratory findings, SC administration was deemed as a promising alternative to IV injection10. These outcomes were subsequently confirmed in the randomized, prospective MMY-3021 study involving RRMM patients11–13 which led to the 2012 approval of SC Btz in the United States and European Union. However, despite several other reports supporting the use of SC Btz,14, 15, there is very limited data available about the safety and efficacy profile of SC Btz in Chinese and Asian patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM)16–19. Few studies with small cohorts compared the two administration routes in Asian patients20, 21.

Promising results from our preliminary studies showed that SC Btz significantly decreases and delays PN in RRMM and particularly in NDMM, prompting this follow-on study to look at a larger cohort of patients with NDMM. We report, for the first time, that patients with IV btz may have quicker and deeper response, especially in PAD group compared to SC group. This has significant relevance in practice. This is also the largest cohort of Asian patients and demonstrates the relevance of SC vs IV administration of bortezomib in this population.

Materials and Methods

Patients and study design

This retrospective, historical control study was conducted at a single center and its design was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Blood Diseases Hospital at Tianjin, China. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in this study. Data from 307 NDMM patients treated with a Btz-based regimen at the Lymphoma & Myeloma Center of this Blood Diseases Hospital between May 1, 2008, and December 31, 2014 was abstracted from the medical records and subsequently analyzed.

Patients were assigned to receive Btz-based regimens, including PAd/BCd [Btz 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8 and 11; adriamycin 9 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1–4; or CTX 500mg/m2, orally on days 1, 8, 15, and dexamethasone 20 mg/day, orally or intravenously on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11 and 12]. Btz was administered by either intravenous injection (IV) (historical control IV group) before Feb 28, 2012 or subcutaneous injection (SC group) after March 1, 2012. The IV injections were administered at a concentration of 1mg/mL as a 3–5s intravenous push, while SC injections were administered at 2.5mg/mL to limit total volume. All treatments were repeated every 3–4 weeks. After at least four cycles of treatment, patients underwent consolidation therapy with either autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) (if patient was <65 years old and without contraindication to ASCT) combined with the original chemotherapy regimen or only the original chemotherapy regimen. After up to nine cycles of induction and consolidation chemotherapy, patients were maintained with either thalidomide or lenalidomide, plus dexamethasone. Where necessary, patients also received supportive treatment with zoledronic acid every 1–2 months. All patients received prophylactic acyclovir.

Patients who completed ≥one dose of Btz were included in this study, and the data on their demographic characteristics and disease profiles [including sex, age, M-protein type and quantity, DS, ISS and RISS22 staging, percentage of plasma cells in bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB), cytogenetics characteristics detected by conventional karyotype and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), etc] were collected. The presence or absence of peripheral neuropathy (PN) and diabetes mellitus (DM) at baseline was obtained before treatment. CD138-purified plasma cells were used to identify cytogenetic abnormalities in FISH analyses.

Assessment of treatment safety and efficacy

Safety analysis was based on all patients who received ≥one dose of Btz. Safety was monitored for 30 days after the last dose by grading the toxicities based on the National Cancer Institute’s Common Toxicity Criteria (version 3.0). Toxicity-related therapeutic adjustments were recorded along with the dose at which PN was induced or aggravated. For IV patients, PN was managed using a dose-modification guideline developed based on experience in phase II studies9. As for SC patients, an updated stricter dose-modification guidelines was used23.

Efficacy analysis was based on all patients who completed ≥one cycle of the Btz-based regimen. In both groups, disease status was assessed after every cycle of induction and consolidation chemotherapy, and once every 3 months during maintenance therapy, in accordance with the International Myeloma Working Group’s uniform response criteria for MM, incorporating near complete response (nCR)24. Progression-free survival (PFS) is defined as the time from the start of the treatment to disease progression or death (regardless of cause), whichever comes first. Overall survival (OS) is defined as the time elapsed between treatment initiation and death. The efficacy and safety of Btz administration via SC and IV were then compared.

Statistical considerations

The data are presented as median±standard deviation (SD). Independent samples of nonparametric tests were used to compare the difference between the two groups. Spearman association and logarithmic regression analyses were performed. Survival was estimated according to the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Two-tailed tests were used with p-value ≤0.05 indicating statistical significance. The SPSS 23.0 software package was used.

Results

Patients: Comparable baseline characteristics between IV and SC group

Among the total 307 patients enrolled in our study, 140 received IV Btz, while 167 received SC Btz. The summary of the baseline characteristics of all patients is listed in Table 1. Overall patients from 22 Chinese provinces were diagnosed and treated at the same Lymphoma & Myeloma Center of the Blood Diseases Hospital, with the majority (92.8%) from 10 northern provinces of China. The median age of the cohort was 56 (25–77) years. Patient demographics and all other baseline characteristics (including age, M-protein type and quantity, percentage of plasma cells in BM and PB, ISS, R-ISS, risk-group according to cytogenetics characteristics, PN and DM before treatment, etc.) were similar between the IV and SC groups. About 60.7% (85/140) of patients in the IV group and 61.1% (102/167) patients in the SC group received PAd regimen, while the remaining patients in both group received BCd (p=0.948).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in IV group and SC group

| Characteristics | Median value or percentage of patients (range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| IV group | SC group | p value | |

| Gender (male/female) | 95/45 | 95/72 | 0.049 |

|

| |||

| Age | 56 (26–77) | 56 (25–76) | 0.442 |

|

| |||

| Albumin (ALB) (g/L) | 34.4 (16.4–49.1) | 35.8 (13.2–50.5) | 0.214 |

|

| |||

| β2-Microglobulin (mg/L) | 5.135 (1.04–105.94) | 5.05 (1.5–58.1) | 0.245 |

|

| |||

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, IU/L) | 157 (57–284) | 169 (69–824) | 0.088 |

|

| |||

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 84.3 (37–674) | 90.45 (45–697) | 0.337 |

|

| |||

| Serum M-protein (g/L) | 27.1 (1.88–152) | 23.2 (1.7–184) | 0.175 |

|

| |||

| Plasma cell of BM (smear, %) | 33 (0–93) | 30 (0.5–93.5) | 0.209 |

|

| |||

| M-spike isotype | 0.648 | ||

| IgG | 78 (55.7%) | 82 (49.1%) | |

| IgA | 23 (16.4%) | 37 (22.2%) | |

| IgD | 10 (7.1%) | 6 (3.6%) | |

| IgM | 1 (0.7%) | - | |

| Double colonies | - | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Light Chain | 25 (17.9%) | 38 (22.8%) | |

| Non-secrete | 3 (2.1%) | 3 (1.8%) | |

|

| |||

| Conventional cytogenetics karyotype | n=108 | n=134 | |

| Hypodiploidy | 11 (10.2%) | 8 (6.0%) | 0.637 |

| Del(13) | 9 (8.3%) | 7 (5.2%) | 0.131 |

|

| |||

| del(13) in FISH | n=110 | n=163 | 0.464 |

| (+) | 47 (42.7%) | 77 (47.2%) | |

|

| |||

| del(17p) in FISH | n=106 | n=164 | 0.380 |

| (+) | 12 (11.3%) | 23 (15.1%) | |

|

| |||

| Amplification of 1q21 in FISH | n=88 | n=148 | 0.739 |

| (+) | 43 (48.9%) | 69 (46.6%) | |

|

| |||

| IgH translocation in FISH | n=108 | n=163 | 0.521 |

| (+) | 56 (51.9%) | 91 (55.8%) | |

|

| |||

| Type of IgH translocation | n=56 | n=91 | |

| IgH/CCND1 | 25 (44.6%) | 28 (30.8%) | 0.963 |

| IgH/MAF | 6 (10.7%) | 9 (9.9%) | 0.443 |

| IgH/FGFR3 | 18 (32.1%) | 25 (27.5%) | 0.303 |

| CCND1/MAF/FGFR3(−) | 3 (5.4%) | 15 (16.5%) | |

| Not discriminated further | 4 (7.1%) | 14 (15.4%) | |

|

| |||

| International staging system (ISS) | n=135 | n=160 | 0.941 |

| I | 24 (17.8%) | 37 (23.1%) | |

| II | 49 (36.3%) | 43 (26.9%) | |

| III | 62 (45.9%) | 80 (50.0%) | |

|

| |||

| Risk group according to FISHi | n=99 | n=153 | 0.810 |

| High-risk | 29 (29.3%) | 47 (30.7%) | |

|

| |||

| Revised ISSii | n=114 | n=151 | 0.383 |

| I | 9 (7.9%) | 21 (13.9%) | |

| II | 71 (62.3%) | 87 (57.6%) | |

| III | 34 (29.8%) | 43 (28.5%) | |

|

| |||

| PN | n=115 | n=141 | 0.514 |

| None | 109 (94.8%) | 136 (96.5%) | |

| Grade 1 | 5 (4.3%) | 4 (2.8%) | |

| Grade 2 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.7%) | |

|

| |||

| Diabetes mellitus | n=110 | n=155 | 0.364 |

| Yes | 9 (8.2%) | 18 (11.6%) | |

Risk group according to FISH: high-risk CA, del(17p) and/or t(4;14) and/or t(14;16)]; standard risk (all others).

Revised ISS: ISS stage I, serum β2-microglobulin level < 3.5 mg/L and serum albumin level ≥ 3.5 g/dL, no high-risk CA [del(17p) and/or t(4;14) and/or t(14;16)], and normal LDH level (less than the upper limit of normal range); R-ISS III, ISS stage III (serum β2-microglobulin level > 5.5 mg/L) and high-risk CA or high LDH level; and R-ISS II, including all the other possible combinations.

Safety profile: SC Btz has a better safety profile and is associated with less severe PN

Adverse events (AEs) associated with IV Btz and SC Btz are listed in Tables 2 and 3. Patients who received IV Btz had more frequent grade ≥3 AEs compared to those who received SC Btz. PN remained to be one of the most common and important Btz-related AE that greatly affects patients’ quality of life. Although the overall incidence of PN was only slightly lower in patients receiving SC Btz than those receiving IV Btz (49.7% vs 57.1%, p=0.154), the frequency of grade ≥3 PN was significantly less in SC group (8.4% grade 3, none grade ≥4) compared to IV group (20.7% grade 3, 2.1% grade 4, p=0.002). Importantly, the median dosage of Btz associated with PN development was higher in SC group (Table 2, Figure 1). Compared with the risk of PN development in IV group, the risk in SC group is 0.561 (95% CI 0.411–0.765). When compared with the risk of grade≥2 PN development in IV group, the risk in SC group is only 0.349 (95% CI 0.217–0.559). Subgroup analysis showed that patients tolerated significantly higher doses to develop/worse PN when Btz was administered SC versus IV independent of whether doxorubicin or cyclophosphamide was used. In patients with PN who received long-term follow-up, the resolution rate was not significantly different between the SC and IV groups. A total of 68.1% and 77.3% patients in SC and IV groups, respectively, showed improvement to a lower grade of PN, or even complete resolution (p=0.215). However, the median time to improvement was shorter in SC versus IV group (5 vs. 7.5 months, respectively; p<0.001). This was observed both in patients receiving PAd (5 vs. 10 months, respectively; p<0.001) or BCd (4.5 vs. 6.5 months respectively; p=0.028). There were also fewer patients who developed ≥grade 3 fatigue, paralytic ileus, and constipation in SC group. These AEs may also be related to the neuropathic toxicity of Btz (Table 3). Additionally, there were significantly fewer ≥grade 3 hematologic toxicities (i.e. leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia) and infections in the SC group (Table 3). Notably, 11 out of 167 (6.6%) patients had ≥one SC injection-site reactions reported as an adverse event that however did not require dose-adjustment. Based on these observations, SC Btz was found to have a better safety profile, especially with regards to PN.

Table 2.

Summary of peripheral neuropathy (grade, developing time, and outcome)

| IV group | SC group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| incidence of peripheral neuropathy (PN) | n=140 | n=167 | |

| Any grade | 80 (57.1%) | 83 (49.7%) | 0.154 |

| Grade 1 | 34 (24.3%) | 54 (32.2%) | 0.121 |

| Grade 2 | 14 (10.0%) | 16 (9.6%) | 0.902 |

| Grade 3 | 29 (29.7%) | 13 (7.8%) | 0.002 |

| Grade 4 | 3 (2.4%) | - | |

|

| |||

| Median dosage of Btz when PN developed | (15.6±0.328)mg/m2 | (20.8±1.017) mg/m2 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| median dosage of btz when PN≥ grade 2 | (26.0±4.346)mg/m2 | NA | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Outcome of PN | n=75 | n=69 | 0.215 |

| Not resolved | 17 (22.7%) | 22 (31.9%) | |

| Improved | 58 (77.3%) | 47 (68.1%) | |

|

| |||

| Time for recovery from PN (month) | 7.5 (1–36) | 5.0 (0.3–12) | <0.001 |

Table 3.

Summary of other adverse events

| Adverse events | IV group (466.5 cycles) | SC group (684.5 cycles) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection: Any grade | 98 (21.0%) | 108 (15.8%) | 0.154 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 89 (19.1%) | 38 (5.6%) | 0.005 |

|

| |||

| Leukopenia: Any grade | 197 (42.2%) | 138 (20.2%) | 0.065 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 103 (22.1%) | 42 (6.1%) | 0.006 |

|

| |||

| Anemia: Any grade | 175 (37.5%) | 134 (19.6%) | 0.098 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 86 (18.4%) | 38 (5.6%) | 0.009 |

|

| |||

| Thrombocytopenia: Any grade | 249 (53.4%) | 178 (26.0%) | 0.041 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 183 (39.2%) | 73 (10.7%) | 0.005 |

|

| |||

| Fatigue: Any grade | 144 (30.9%) | 108 (15.8%) | 0.235 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 25 (5.4%) | 15 (2.2%) | 0.004 |

|

| |||

| Constipation: Any grade | 92 (19.7%) | 89 (13.0%) | 0.154 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 26 (5.6%) | 7 (1.0%) | 0.003 |

|

| |||

| Diarrhea: Any grade | 37 (7.9%) | 65 (9.5%) | 0.207 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 15 (3.2%) | 7 (1.0%) | 0.122 |

|

| |||

| Abdominal distension: Any grade | 58 (12.4%) | 78 (11.4%) | 0.650 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 18 (3.9%) | 12 (1.8%) | 0.094 |

|

| |||

| Paralytic ileus: Any grade | 22 (4.7%) | 26 (3.8%) | 0.431 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 17 (3.6%) | 6 (0.9%) | 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Hypotension: Any grade | 7 (1.5%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0.236 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 5 (1.1%) | 0 | 0.058 |

|

| |||

| Hypertension: Any grade | 30 (6.4%) | 28 (4.1%) | 0.945 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 4 (0.9%) | 2 (0.3%) | 0.801 |

|

| |||

| Hyperglycemia: Any grade | 168 (36.0%) | 215 (31.4%) | 0.405 |

| ≥ grade 3 | 27 (5.8%) | 31 (4.5%) | 0.275 |

Figure 1.

Median estimated bortezomib dosage to develop PN (left) and to develop≥ grade2 PN (right). Median estimated bortezomib dosage to develop PN is (15.6±0.328) mg/m2 in IV group and (20.8±0.328) mg/m2 in SC group. Median estimated bortezomib dosage to develop ≥ grade2 PN is (26.0±4.346) mg/m2 in IV group and NA (not arrived) in SC group.

Btz dosing: Patients in SC group received a higher dose of Btz

One hundred and forty individuals in IV group completed 466.5 cycles of Btz-based chemotherapy, with a median of 3 (0.5–9) cycles/patient; while 167 patients in SC group, completed 684.5 cycles of Btz-based chemotherapy with a median of 4 cycles (0.5–9) /patient. The rate of dose reduction or delay in administration of Btz was not significantly different between the SC and IV group (28.7% vs 29.3%, p=0.917) (Table 4). The median Btz dose at the time of first reduction or delay (if any at all) was higher in SC compared to IV group (15.6 mg/m2 vs 7.8 mg/m2, p<0.001). Fewer patients discontinued SC Btz (failed to complete at least 8 cycles) compared to IV Btz (71.9% vs 96.4%, respectively; p<0.001). Overall, the cumulative dose of Btz delivered was significantly higher in SC- compared to IV-treated patients (20.8mg/m2 vs 15.6mg/m2 respectively, p<0.001). No significant difference was noted between PAd and BCd groups.

Table 4.

Reasons for reducing/delaying and discontinuing Btz treatment

| reduction or delay of Btz treatment | discontinuing Btz treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| IV group (n, %) | SC group (n, %) | IV group (n, %) | SC group (n, %) | ||

| PN | 21 (15.0%) | 30 (18.0%) | AEs | 59 (42.1%) | 23 (13.8%) |

|

|

|||||

| Diarrhea or paralytic ileus | 9 (6.4%) | 3 (1.8%) | PN | 38 (27.1%) | 17 (10.2%) |

|

|

|||||

| Infection | 7 (5.0%) | 5 (3.0%) | Diarrhea | 1 (0.7%) | - |

|

|

|||||

| Other AEs | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | Intestinal obstruction | 6 (4.3%) | 2 (1.1%) |

|

|

|||||

| Patients’ intent | - | 5 (3.0%) | Infection | 13 (9.3%) | 3 (1.8%) |

|

|

|||||

| Economics difficulty | 2 (1.4%) | - | Other AEs | 1 (0.71%) | 1 (0.6) |

|

| |||||

| Combined with itraconazole or voriconazole | - | 4 (2.4%) | Inferior efficacy (SD/PD) | 4 (2.9%) | 6 (3.6%) |

|

| |||||

| Patients’ intent | 10 (7.1%) | 49 (29.3%) | |||

|

| |||||

| Economics difficulty | 61 (43.6%) | 42 (25.1%) | |||

|

| |||||

| Dead | 1 (0.7%) | - | |||

IV Btz achieves similar ORR, PFS and OS but rapider response and higher ≥VGPR rate compared to SC Btz

At median follow-up of 18.5 (1–41) months in the SC group, and 41 (1–84) months in the IV group, the median PFS and OS were similar between the 2 groups (PFS: not arrived vs 33.0±2.7 months respectively, p=0.976; and OS: not arrived vs 56.0 months respectively, p=0.425) (Figure 2). The median number of cycles to initial response was 1 (1–4) in both the IV and SC groups (P=0.396). The majority patients in both groups (92.3% in IV group, and 82.5% in SC group) achieved ≥MR after only one cycle of Btz-based therapy. However, the depth of the initial response between these two groups was significantly different (p=0.001) with better response in the IV versus SC group after 1 cycle of chemotherapy [77.7% ≥partial response (PR), with 22.3% ≥very good partial response (VGPR) in IV Btz versus 61.7% ≥PR, with 13.0% ≥VGPR in SC Btz]. MR was achieved by 14.6% of the patients in IV group and 20.8% in SC group (Table 5). The ORR (≥PR) was similar between the 2 groups (96.2% vs 94.8%). However, VGPR or higher response was achieved more frequently with IV Btz versus SC Btz (75.0% vs 63.2% respectively; p=0.014) (Tables 5).

Figure 2.

Progression free survival (PFS, left) and overall survival (OS, right) of patients in IV group and SC group. After a median follow-up of 23 (1–84) months, no significant difference in median (PFS: not arrived vs 33.0±2.735 months, left) and OS (not arrived vs 56.0 months, right) was noted.

Table 5.

The primary response after 1 cycle and the best response across all cycles

| primary response | best response across all cycles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV group (n=130) | SC group (n=154) | p value | IV group (n=132) | SC group (n=155) | p value | |

| CR/nCR | 22 (16.9%) | 12 (7.8%) | 0.018 | 60 (45.5%) | 62 (40.0%) | 0.352 |

| ≥VGPR | 29 (22.3%) | 20 (13.0%) | 0.039 | 99 (75.0%) | 98 (63.2%) | 0.014 |

| ≥PR | 101 (77.7%) | 95 (61.7%) | 0.004 | 127 (96.2%) | 143(94.8%) | 0.224 |

| ≥MR | 120 (92.3%) | 127 (82.5%) | 0.014 | 128 (96.9%) | 150 (97.4%) | 0.818 |

Discussion

Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN) is a major dose-limiting adverse effect which was first observed during phase I studies25, and also corroborated in the later phases of clinical studies9, 26, 27. Multiple interventions have been (and are being) investigated in a bid to decrease the incidence and severity of BIPN. The administration of Btz via SC route was one such intervention which was reported to be associated with a lower incidence of BIPN in a phase 3 study comparing IV versus SC Btz11, 13.

In this context, our study is the first comparison of IV versus SC Btz in Chinese patients with NDMM. Our analysis confirmed that Btz administration via SC offers a comparable efficacy (ORR and survival), with the added advantage of an improved safety profile consistent with earlier reports (CAN-1004 and MMY-3021 trials for RRMM, GMMG-MM5 trial for NDMM)10–13, 28.

Patients in our SC group tolerated Btz better than those in IV group. SC Btz was associated with lower incidence and severity of PN, consistent with the reported findings from MMY-3021 and GMMG-MM5. It is of note that we followed the updated stricter dose-modification guidelines for Btz-related neuropathic pain and/or peripheral sensory or motor neuropathy23 in SC group. Importantly, fewer patients in SC group discontinued Btz because of AEs, especially due to PN, which allowed these patients to receive more cycles of chemotherapy and a higher total dosage of Btz. Regrettably, one of the main reasons for discontinuing Btz was the financial hardship brought about by the high cost of Btz coupled with the denial of medical insurance coverage in China. As a result, both the median number of cycles and total dose of Btz are lower in our study when compared to other published reports. Notably, one other retrospective study14 reported that SC Btz induces similar therapeutic response rates as intravenous Btz in MM without the reduction in incidence of PN. However, this study used once weekly Btz, and subgroup analysis revealed a higher percentage of patients had pre-existing neuropathy in the SC versus IV arm (18% in SC arm vs 13% in IV arm, p=0.073). In addition, the incidence and severity of non-PN AEs (especially hematological AEs) are also lower in our SC versus IV cohort. In our study, the incidence of ≥ grade 3 infection is much higher in IV group than in that in SC group. This phenomenon is in accordance with the significant higher incidence of ≥grade leukopenia in IV group, which is the high-risk factor for severe infection.

In our analysis, IV Btz, on the other hand, has the advantage of bringing about quicker and deeper response compared to SC administration. After one cycle of chemotherapy, more patients achieved ≥PR in IV group than SC group. Even though the median number of cycles to initial response was 1 in both groups, the depth of initial response was better in IV versus SC group. As for the best response across all cycles, a greater percentage of patients in IV group achieved ≥VGPR, even though median 1 more cycle of Btz-based chemotherapy was administrated in SC group compared to that in IV group. The MMY-3021 trial also reported a median time to initial response of 1.4 months in both groups (SC and IV) in RRMM patients; however, they did not illustrate the detailed depth of the initial response11. In the GMMG-MM5 trial, subgroup analysis revealed that patients with baseline creatinine ≥2mg/dL who were treated with IV BCd had much higher rates of nCR/CR (47% in IV group vs. 11% in SC group, p=0.03), while patients with adverse cytogenetic abnormalities who were treated with IV PAD had much higher ≥VGPR rates than those treated with SC Btz (45% in IV group vs. 29% in SC group, p=0.05). Similar phenomena were also noticed in the whole BCD arm (≥VGPR, 42% in IV group vs. 29% in SC group, p=0.02; nCR/CR, 27% in IV group vs. 14% in SC group, p=0.01)28. Previous pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics studies have documented that the IV administration of Btz has a higher Cmax and a shorter Tmax compared to SC administration13. These two pharmacokinetic factors seem to have an impact on time to response and may partly explain the deeper response observed in our IV group. The comparable ORR could be due to the overall equivalent systemic exposure of Btz between the SC and IV groups10, 11. This study raises interesting question about possible pharmacokinetics differences in Chinese population. We plan to study this in future. Importantly, it also brings about a point that IV may have quicker effect which may have clinical significance especially in newly-diagnosed patients and patients with renal dysfunction or aggressive disease where a quicker response may be advantageous. Whereas for patients with indolent diseases, SC Btz can get better balance between efficacy and toxicity. This phenomenon also provides us the possibility to administer Btz by IV first to rapid control disease, then followed by SC to get better tolerance.

We have observed higher ORR in our study compared to other studies comparing IV vs SC Btz mainly because, unlike other studies, we studied patients with NDMM and received three-drug regimens as initial therapy. Similar responses have been reported with other three-drug regimens such PAd, BCd, VRd, BCd-modified in NDMM (88–100%)4–6, 15, 29–31.

There are some limitations to this study. First, this study is not a prospective randomized controlled trial. Second, Btz was not administrated during the same period in the IV and SC groups. Third, Subgroup analysis lack power as the cohort size is not sufficiently large especially for the different cytogenetic subgroups. Lastly, the differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics between SC and IV administration of Btz in Chinese patients was not studied which represents a missed opportunity as race or ethnicity is known to play a key role in inter-patient variability in drug response32. Thus, a randomized controlled trial with a larger cohort of enrolled patients and longer follow-up times will be required to conclusively address these issues in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report that, compared with IV administration, SC administration of Btz, when combined with Adriamycin or cyclophosphamide, results in significantly reduced toxicity and similar ORR, PFS, and OS. Thus, SC administration is an acceptable alternative for Chinese NDMM patients due to its superior safety profile and similar ORR and survival. However, IV administration of Btz leads to rapider and deeper responses in these patients. This study raises the point that SC Btz can provide better balance between efficacy and toxicity, especially for patients with indolent diseases. While IV Btz may control tumor load more rapidly, which maybe preferred in patients with more aggressive diseases or renal failure.

Clinical Practice Points.

The use of bortezomib (Btz) have greatly improved overall survival (OS) and shifted treatment paradigms in MM but peripheral neuropathy (PN) is an important toxicity. Attempts to reduce PN have included its subcutaneous (SC) administration.

We retrospectively compared the efficacy and safety of Btz administration via SC and IV in 307 newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients from a single Chinese center.

We found that the estimated median Btz dosage when PN developed was higher (20.8 mg/m2 vs 15.6 mg/m2) and fewer patients reduced or discontinued Btz due to AEs in SC compared to IV group.

The overall response rate (≥PR) and survival (PFS and OS) were comparable between these two groups.

Patients in IV group required fewer cycles to achieve partial response (PR) and larger proportion of patients in IV group achieved ≥VGPR, though higher totally Btz dosage was used in SC group.

We report, for the first time, that SC Btz is associated with better tolerance, while quicker and deeper responses can be achieved by IV Btz in Chinese NDMM patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the doctors, nurses, and biologists who are based at the Department of Lymphoma & Myeloma, Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, China, both for their patient care and for their contribution to data collection. We also thank Dr. Sonal Jhaveri for her help in manuscript writing.

Funding sources

This work was supported by grants from National Nature Science Foundation of China (#81630007; #81101794); Foundation of Education Ministry of China (#20101106120026); Science and Technology Infrastructure Program of Tianjin (#12ZCDZSY17600); Ron and Anita Wornick fund; NIH grants PO1-155258 and P50-100707; and Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award 1 I01BX001584-01 (NCM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

Research designing: Lugui Qiu, Shuhui Deng, Yan Xu. Clinical treatment: Chenxing Du, Dehui Zou, Gang An, Hong Liu, Jian Li, Lugui Qiu, Rui Lv, Shuhua Yi, Shuhui Deng, Tingyu Wang, Wei Liu, Weiwei Sui, Wenyang Huang, Xuehan Mao, Yan Xu, Zengjun Li. Data collecting and analysising: Chenxing Du, Gang An, Shuhui Deng, Weiwei Sui, Xuehan Mao, Yan Xu, Zengjun Li. Paper writing: Jianhong Lin, Lugui Qiu, Mariateresa Fulciniti, Matthew Ho, Nikhil Munshi, Shuhui Deng, Yafei Wang, Yan Xu.

All authors have stated that they have no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Harousseau JL, Attal M, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone is superior to vincristine plus doxorubicin plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the IFM 2005-01 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4621–4629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.9158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster M, et al. Extended follow-up of a phase 3 trial in relapsed multiple myeloma: final time-to-event results of the APEX trial. Blood. 2007;110:3557–3560. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-036947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lonial S, Kaufman J, Tighiouart M, et al. A phase I/II trial combining high-dose melphalan and autologous transplant with bortezomib for multiple myeloma: a dose- and schedule-finding study. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5079–5086. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet. 2010;376:2075–2085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig H, Viterbo L, Greil R, et al. Randomized phase II study of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without cyclophosphamide as induction therapy in previously untreated multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:247–255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leiba M, Kedmi M, Duek A, et al. Bortezomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone (VCD) versus bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone (VTD) -based regimens as induction therapies in newly diagnosed transplant eligible patients with multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Br J Haematol. 2014;166:702–710. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barta SK, Jain R, Mazumder A, et al. Pharmacokinetics-directed Intravenous Busulfan Combined With High-dose Melphalan and Bortezomib as a Conditioning Regimen for Patients With Multiple Myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voorhees PM, Gasparetto C, Moore DT, Winans D, Orlowski RZ, Hurd DD. Final Results of a Phase 1 Study of Vorinostat, Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin, and Bortezomib in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson PG, Briemberg H, Jagannath S, et al. Frequency, characteristics, and reversibility of peripheral neuropathy during treatment of advanced multiple myeloma with bortezomib. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3113–3120. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreau P, Coiteux V, Hulin C, et al. Prospective comparison of subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2008;93:1908–1911. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreau P, Pylypenko H, Grosicki S, et al. Subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70081-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnulf B, Pylypenko H, Grosicki S, et al. Updated survival analysis of a randomized phase III study of subcutaneous versus intravenous bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2012;97:1925–1928. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.067793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreau P, Karamanesht II, Domnikova N, et al. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and covariate analysis of subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51:823–829. doi: 10.1007/s40262-012-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minarik J, Pavlicek P, Pour L, et al. Subcutaneous bortezomib in multiple myeloma patients induces similar therapeutic response rates as intravenous application but it does not reduce the incidence of peripheral neuropathy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong SY, Ng HY, Surendran S, et al. Subcutaneous bortezomib combined with weekly cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone is an efficient and well tolerated regime in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2015;169:754–756. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H, Fu CC, Xue SL, et al. Efficacy and safety study of subcutaneous injection of bortezomib in the treatment of de novo patients with multiple myeloma. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2013;34:868–872. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang YS, Ding SH, Wu F, Wang ZT, Wang QS. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous administration of bortezomib in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2014;45:529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Wang KF, Chang BY, Chen XQ, Xia ZJ. Once-weekly subcutaneous administration of bortezomib in patients with multiple myeloma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:2093–2098. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.5.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu S, Zheng C, Chen S, et al. Subcutaneous Administration of Bortezomib in Combination with Thalidomide and Dexamethasone for Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Patients. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:927105. doi: 10.1155/2015/927105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koh Y, Lee SY, Kim I, et al. Bortezomib-associated peripheral neuropathy requiring medical treatment is decreased by administering the medication by subcutaneous injection in Korean multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:653–657. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, Xu R, Huang H. Peripheral neuropathy outcomes and efficacy of subcutaneous bortezomib when combined with thalidomide and dexamethasone in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3041–3046. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, et al. Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: A Report From International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2863–2869. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson PG, Delforge M, Beksac M, et al. Management of treatment-emergent peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2012;26:595–608. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aghajanian C, Soignet S, Dizon DS, et al. A phase I trial of the novel proteasome inhibitor PS341 in advanced solid tumor malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2505–2511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2609–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagannath S, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. A phase 2 study of two doses of bortezomib in relapsed or refractory myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:165–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merz M, Salwender H, Haenel M, et al. Subcutaneous versus intravenous bortezomib in two different induction therapies for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an interim analysis from the prospective GMMG-MM5 trial. Haematologica. 2015;100:964–969. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.124347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oakervee HE, Popat R, Curry N, et al. PAD combination therapy (PS-341/bortezomib, doxorubicin and dexamethasone) for previously untreated patients with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:755–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeder CB, Reece DE, Kukreti V, et al. Long-term survival with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone induction therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2014;167:563–565. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar S, Flinn I, Richardson PG, et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase 2 study (EVOLUTION) of combinations of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and lenalidomide in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:4375–4382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-395749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasuda SU, Zhang L, Huang SMM. The role of ethnicity in variability in response to drugs: focus on clinical pharmacology studies. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2008;84:417–423. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]