Abstract

Objective

Thrombophilia is a major complication in preeclampsia (PE), a disease associated with placental hypoxia and trophoblast inflammation. PE women are known to have increased circulating microparticles (MPs) that are pro-coagulant, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, we sought to understand the mechanism connecting placental hypoxia, circulating MPs and thrombophilia.

Approach and Results

We analyzed protein markers on plasma MPs from PE women and found that the increased circulating MPs were mostly from endothelial cells. In proteomic studies, we identified high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a pro-inflammatory protein, as a key factor from hypoxic trophoblasts in stimulating MP production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Immunodepletion or inhibition of HMGB1 in the conditioned medium from hypoxic human trophoblasts abolished the endothelial MP-stimulating activity. Conversely, recombinant HMGB1 (rHMGB1) stimulated MP production in cultured HUVECs. The MPs from rHMGB1-stimulated HUVECs promoted blood coagulation and neutrophil activation in vitro. Injection of rHMGB1 in pregnant mice increased plasma endothelial MPs and promoted blood coagulation. In PE women, elevated placental HMGB1 expression was detected and high levels of plasma HMGB1 correlated with increased plasma endothelial MPs.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that placental hypoxia-induced HMGB1 expression and release from trophoblasts are an important mechanism underlying increased circulating endothelial MPs and thrombophilia in PE.

Keywords: blood coagulation, endothelial cells, HMGB1, microparticles, preeclampsia, thrombophilia

Subject Codes: pathophysiology, pregnancy, thrombosis, vascular biology

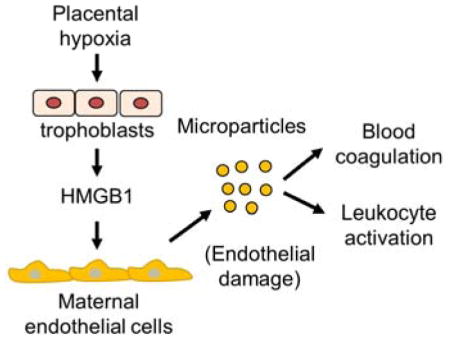

Graphic Abstract

In preeclampsia, placental hypoxia induces HMGB1 expression and release from trophoblasts. High levels of plasma HMGB1 cause maternal endothelial damage and endothelial microparticle production, which in turn enhance blood coagulation and leukocyte activation.

Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a major complication in pregnancy that increases maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.1, 2 Placental hypoxia, caused by impaired uterine spiral artery remodeling and reduced uteroplacental blood flow, plays a central role in the pathophysiology of PE, which includes chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, tissue ischemia, and proteinuria.1–6

Pregnancy is often accompanied by a mild hypercoagulable state,7–12 which may be evolved to prevent excessive bleedings at childbirth. In PE, enhanced blood coagulation is more substantial, which increases the thrombotic risk.1, 7, 10, 11 Despite the clinical importance, the mechanisms underlying PE-associated thrombophilia are not fully understood.

Microparticles (MPs) from activated or apoptotic cells are pro-coagulant and pro-thrombotic.13–15 In PE, increased circulating MPs from blood cells, endothelial cells and placental trophoblasts have been reported.14, 16–19. These MPs promote thrombus formation and reduce uteroplacental blood flow, which in turn exacerbate placental hypoxia and inflammation.16, 20–22 Such a vicious cycle is part of the PE pathophysiology. To date, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura has been reported to increase the risk of PE.23 It remains unclear, however, which cell types are the primary source of the circulating MPs in PE women and how these MPs are generated.

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a pro-inflammatory protein.24, 25 It causes endothelial dysfunction26, 27 and promotes leukocyte activation and thrombosis.28–30 Increased HMGB1 expression has been reported in the placenta or placental explant-derived extracellular vesicles from PE patients.31–34 High levels of RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end-products), an HMGB1 receptor, were also found in PE sera.35 In culture, trophoblast-derived HMGB1 increased endothelial cell permeability in a TRL4- and Caveolin-1-dependent mechanism.36 These data suggest a potential role of HMGB1 in PE.

In this study, we sought to understand the mechanism connecting placental hypoxia, maternal endothelial dysfunction and increased thrombotic risk in PE. We examined plasma MPs in PE women, analyzed human trophoblasts under normoxia and hypoxia, did proteomic analysis of trophoblast-secreted proteins, conducted experiments in pregnant mice, and tested placental tissues from PE women. Our results indicate that increased HMGB1 expression and release from hypoxic trophoblasts play an important role in causing maternal endothelial damage and producing endothelial cell-derived MPs that promote blood coagulation in PE.

Materials and Methods

Human plasma and tissue samples

Human blood and placental samples were collected at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the university and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. Participant characteristics are shown in Supplemental Table I. PE was diagnosed by new-onset high blood pressure (≥140/90 mmHg) and proteinuria (≥300 mg/24 h) at ≥20 weeks of gestation.1 Blood coagulation tests were done at the hospital laboratory. Venous blood samples were drawn into tubes with sodium citrate (3.2%) in a 9:1 (v/v) ratio and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min to obtain plasma, which was centrifuged subsequently at 13,000 × g for 2 min. The platelet-free plasma was collected and stored at −80°C until use. For PE women, blood samples were taken before treatment. All participants for placental studies delivered by primary C-section without labor. Placentae were collected immediately after the delivery. Biopsies from the placental center and each quadrant were taken, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Analysis of MPs in human plasma

MPs were analyzed by flow cytometry37 with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-, phycoerythrin (PET)-, or peridinin-chlorophyll-protein complex (PerCP)-conjugated antibodies. Plasma (50 μL) was diluted with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (50 μL) and incubated with an FITC-conjugated anti-annexin V antibody (BD Biosciences, 556547) for total MPs or conjugated-antibodies against platelets (CD41a-FITC, 555467), leukocytes (CD45-PerCP, 347464), red blood cells (CD235a-PET, 340947), endothelial cells (CD31-PET, 555448 or CD62e-PET, 551145) (all from BD Biosciences), tissue factor (Bioss, bs-4690R-PE) or an anti-placental alkaline phosphatase antibody (Abcam, ab33) and a PET-conjugate secondary antibody (BD Biosciences, 550589). Reference beads (5 μL) of known concentrations (Flow-CountTM Fluorospheres; Beckman Coulter, 7547053) were included. Conjugated and isotype-matched control antibodies (IgG1-FITC, 551954; IgG1-PET, 555749; IgG1-PerCP, 559425, BD Biosciences) were used as negative controls. Data were acquired and analyzed with a flow cytometer (Cytomics FC 500; Beckman Coulter).

Human trophoblast culture

Human JEG-3 trophoblasts (ATCC) and primary human villous trophoblasts (HVT) (ScienCell Research Labs) were cultured as described previously.3 Normoxic or hypotonic hypoxia experiments were done with 20% or 1% O2. Histogenous hypoxia experiments were done with rotenone (0.5 μmol/L, TCI Development, China), which disrupts the mitochondrial electron transport chain.38 After 6 h, the medium was replaced with opti-MEM without rotenone for 24 h. To isolate MPs, the conditioned medium was centrifuged at 1,500 g for 15 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000 g, 4°C for 40 min. Pelleted MPs were washed and re-suspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone). The MPs-free supernatant was fractionated with centrifugal filters of different molecular weight cut-offs (Millipore).

Analysis of MPs from HUVECs

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (ATCC) were cultured with RPMI 1640 medium and 10% FBS in 6-well plates and treated with 1.5 mL of the conditioned medium, MPs-free conditioned medium or MPs (2×106/mL) from JEG-3 cells or 100 ng/mL of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (PeproTech) or human rHMGB1 (Sino Biological, China). After 24 h, the medium was collected and HUVEC-derived MPs were analyzed, as described above. To deplete HMGB1 from the trophoblast medium, an anti-HMGB1 antibody (10 μg) (Abcam, ab18256) or control IgG (10 μg) was incubated with the conditioned medium (2 mL) from hypoxic JEG-3 cells at 4°C for 4 h followed by immunoprecipitation to remove the antibody-HMGB1 complex.39 The supernatant (1.5 mL) was added to HUVECs to test the effect on MP production. To inhibit HMGB1 in the hypoxic JEG-3 medium, HMGB1 Box A fragment (2 μg/mL) (HMGBiotech, Italy) or glycyrrhizin (200 μg/mL) (Sigma) was added to the conditioned medium and incubated with HUVECs for 24 h. Endothelial MPs in the medium were examined by flow cytometry.

Proteomic analysis

The conditioned medium from JEG-3 cells cultured without (normal) or with rotenone (hypoxic) was concentrated ~20-fold using Amicon filters (Millipore) with 3-, 50- and 100-kDa molecular weight cut-offs. Proteomic analysis of the isolated proteins was done by in-solution trypsin digestion and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis at Shanghai Applied Protein Technology (China). Identified peptide sequences in the hypoxic, but not normoxic, conditioned medium were searched against the Uniprot database using Mascot 2.2 software.

Analysis of HMGB1 mRNA expression

Total RNAs from cultured trophoblasts or placental tissues were used to make cDNA templates with a reverse transcription kit (Thermo Scientific). HMGB1 mRNA expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR (ABI 7500) with primers 5′-TCA AAG GAG AAC ATC CTG GCC TGT-3′ and 5′-CTG CTT GTC ATC TGC AGC AGC AGT GTT-3′. Primers for β-actin were included as a control.

HMGB1 immunostaining

JEG-3 or HVT cells on coverslips were cultured in incubators with 20% O2 (normoxia) or 1% O2 (hypoxia) for 24 h and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by immunostaining with an anti-HMGB1 antibody (Abcam, ab79823). The coverslips were mounted with DAPI medium (Fluoromount-G, Southernbiotech). Fluorescent images were analyzed under a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1000MPE) with Image J software.40

Western blotting

To analyze HMGB1 protein, JEG-3 and HVT cell lysates and human placental homogenates were prepared.41 Proteins (10 μg per sample) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with an anti-HMGB1 (Abcam, ab79823, 0.0152 μg/mL) or anti-GAPDH (GenScript, Ad00192, 0.05 μg/mL) antibody and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bioworld, BS13278, 0.2 μg/mL). The blot was developed using enhanced chemiluminescent reagents. Immunoreactive bands were quantified using Image J software and normalized with GAPDH values in the same lane.

Apoptosis in JEG-3 and HVT cells

Apoptosis in normoxic and hypoxic JEG-3 and HVT cells was analyzed by flow cytometry using an annexin V-PE/7-AAD apoptosis kit (LianKeBio, China). The cells were detached by trypsin digestion, washed with PBS and labeled with annexin V-PET and 7-AAD at 4°C for 30 min. The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

HMGB1 ELISA

HMGB1 levels in the conditioned media from normoxic and hypoxic JEG-3 and HVT cells and in human plasma were measured by ELISA (Shino-test, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Electron microscopy

MPs from rHMGB1-stimulated HUVECs were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Ourchem, China) in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, at 4°C for 4 h, deposited on the carbon coated grid and treated with 2% phosphotungstic acid (Sigma). Images were taken with a transmission electron microscopy (Tecnai G220, TEI).

HUVEC permeability

The permeability of rHMGB1-treated HUVECs was examined by flow cytometry. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with propidium iodide (PI) at room temperature for 10 min, followed by flow cytometric analysis of PI-staining cell.

Thrombin generation assay

In a fluorimetric assay,42 increasing numbers of HUVEC-derived MPs were added to human plasma. A thrombin fluorogenic substrate (Z-Gly-Gly-Arg-AMC) and CaCl2 (25 mM) were added to the plasma to initiate the reaction. Thrombin generation, as indicated by fluorescent absorbance, was monitored with an automated coagulation analyzer (Ceveron alpha TGA, Technoclone).

DNA released from neutrophils

Human neutrophils were isolated from peripheral blood by dextran sedimentation and Percoll IITM (Amersham Biosciences) gradient methods.43 Neutrophils (1×105/well) were added to 96-well plates and incubated with HUVEC-derived MPs (2×106/mL) or control buffer at 37°C. After 4 h, released DNA in the supernatant was measured by Quant-iT™ PicoGreen dsDNA reagents (Invitrogen).

Effects of rHMGB1 in mice

The study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Soochow University and the experiments were conducted in accordance with the approved protocol. Two-month-old male and female C57BL/6 mice were kept at a specific-pathogen-free facility under 12–12-h light-dark cycles with free access to chow diet and water. Mated female mice were checked for vaginal plugs to establish gestation timing. The day on which a plug was detected was defined as day 0.5 post coitum (p.c.). On day 18.5 p.c., pregnant or age-matched control non-pregnant female mice (n=8 per group) were held transiently in a restrainer and injected with rHMGB1 (50 μg in 200 μL saline) or saline control via tail vein. After 1.5 h, the mice were euthanized and blood was collected via vena cava. Total and endothelial MPs in plasma, blood coagulation, and plasma DNA levels were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was done using SPSS 17.0 and Prism 7 software. Equal variance and normality of the data were verified by Levene’s test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, respectively. If the data passed the normality and equal variance tests, Student’s t test was used to compare two groups or one-way ANOVA followed by Bartlett’s test for comparisons among three or more groups. If the data did not pass the normality or equal variance test, Mann-Whitney test was used for two independent sample comparisons, and Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction were used for multiple comparisons. Correlations were analyzed with the Pearson method. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values <0.05 are considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Plasma MPs in PE women

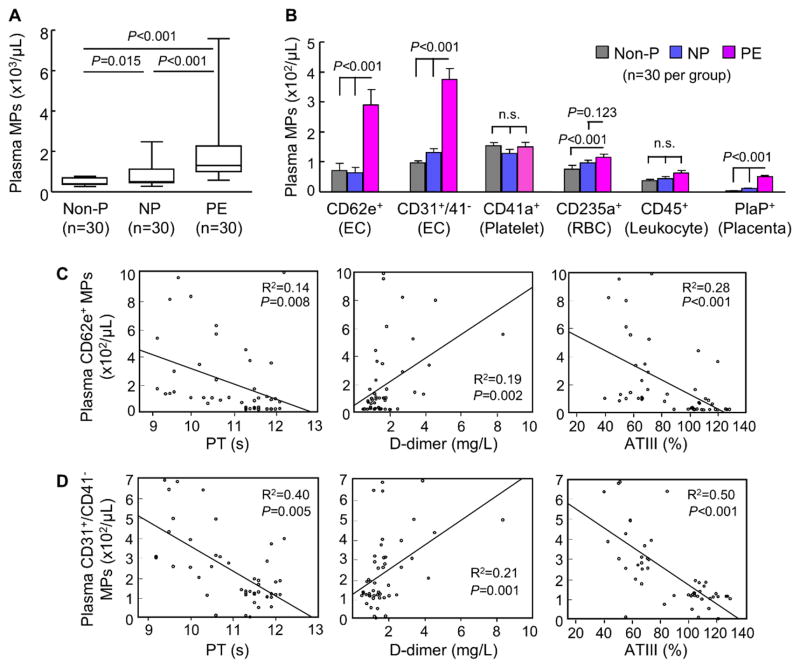

By flow cytometry, we found high levels of plasma MPs in PE women compared with those in non-pregnant and normal pregnant women (Figure 1A). By analyzing protein markers, we found that the increased MPs in PE women were mostly of endothelial origin (CD62e+ and CD31+/41−) (Figure 1B). Levels of trophoblast-derived MPs also increased in PE woman but were ~6-fold less than that of endothelial MPs. In contrast, levels of platelet-, red blood cell- and leukocyte-derived MPs were similar in normal pregnant and PE women (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Analysis of plasma MPs in pregnant women. A, Numbers of total plasma MPs in non-pregnant (Non-P), normal pregnant (NP) and PE women, as analyzed by flow cytometry. Sample numbers (n) are indicated. Data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction. B, Analysis of protein markers on plasma MPs. Markers tested included CD62e+ and CD31+/41− for endothelial cells (EC); CD41a+ for platelets; CD235a+ for red blood cells (RBC); CD45+ for leukocytes and placenta phosphatase (PlaP+) for trophoblasts. Data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction. n.s.: not significant. C and D, Correlations beween CD62e+ (C) or CD31+/41− (D) MPs and prothrombin time (PT) and plasma fibrinogen d-dimer and antithrombin (ATIII) levels in NP and PE women, as analyzed by the Pearson method.

PE is associated with enhanced blood coagulation. We found shortened activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT), high levels of fibrinogen D-dimer and low levels of anti-thrombin III (ATIII) in PE women compared with those in normal pregnant women (Supplemental Figure I). In those individuals, plasma endothelial MP levels correlated with PT, plasma D-dimer and ATIII levels (Figure 1C and 1D), whereas no correlation was found between endothelial MP levels and aPTT (Supplemental Figure II).

Endothelial MP-stimulating activity from trophoblasts

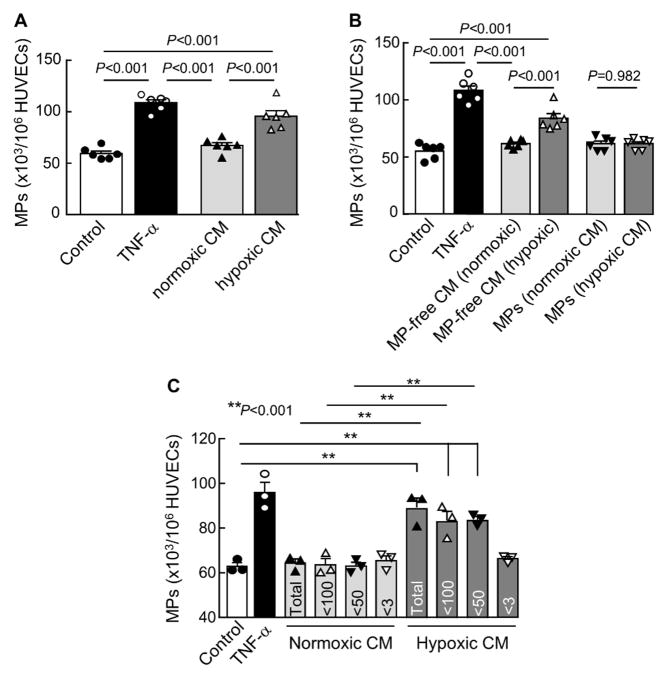

Placental hypoxia plays a key role in PE. High levels of plasma endothelial MPs in PE women suggest that hypoxia may induce trophoblasts to secrete factor(s) to cause maternal endothelial damage and release of MPs. We cultured JEG-3 trophoblasts under normoxic and hypoxic conditions and tested the conditioned medium for MP-stimulating activity in HUVECs. We detected an increased MP-stimulating activity in the conditioned medium from hypoxic, but not normoxic, JEG-3 cells (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

MP production in cultured HUVECs. A, HUVECs were incubated with the conditioned medium (CM) from JEG-3 cells cultured under normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). Control medium (negative) and TNF-α (positive) were controls. MP production was analyzed by flow cytometry. n=6 per group. B, Flow cytometric analysis of MP production from HUVECs incubated with MP-free CM or MPs from trophoblasts cultured under normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). n=6 per group. C, MP production from HUVECs incubated with unfractionated (Total) or fractionated CM with different molecular cut-offs (numbers in kDa) from trophoblasts cultured under normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). Control medium (negative) and TNF-α (positive) were controls. n=3 per group; Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and presented as mean ± SEM.

To exclude the possibility that the activity was from hypoxic JEG-3 cell-derived MPs, we isolated MPs from hypoxic JEG-3 cells and tested the MPs and MP-free medium for the MP-stimulating activity in HUVECs. We found that the activity was associated with the MP-free hypoxic conditioned medium, but not JEG-3 cell-derived MPs (Figure 2B), indicating that secreted factor(s) from hypoxic JEG-3 cells stimulated endothelial MPs in our experiments.

To identify such factor(s), we fractionated the hypoxic JEG-3 cell conditioned medium based on molecular masses and assayed for the MP-stimulating activity in HUVECs. The activity was found in the 3–50 kDa fraction (Figure 2C), indicating that the MP-stimulating activity in the conditioned medium was from protein(s) of 3–50 kDa.

Identification of HMGB1 by proteomic analysis

We prepared the conditioned medium from normoxic and hypoxic JEG-3 cells and did proteomic analysis were to identify differentially expressed proteins. A total of 238 proteins were found in the conditioned medium from hypoxic, but not normoxic, JEG-3 cells, of which 42 were of >100 kDa, 80 were of 50–100 kDa, and 116 were of 5–50 kDa (Supplemental Table II).

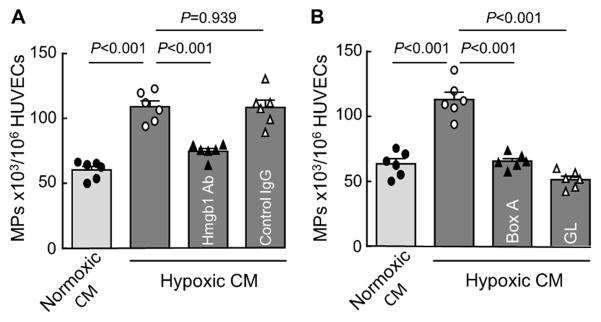

Among the 5–50-kDa fraction, HMGB1, a 25-kDa protein, appeared a candidate. When HMGB1 was immune-depleted from the hypoxic JEG-3 cell medium, the endothelial MP-stimulating activity was reduced (Figure 3A). Moreover, when the hypoxic JEG-3 medium was treated with known HMGB1 inhibitors, HMGB1-derived Box A fragment (HMGB1 Box A)44 and the natural compound glycyrrhizin,45 the endothelial MP-stimulating activity was abolished (Figure 3B), indicating that HMGB1 was a primary factor from the hypoxic JEG-3 cells for stimulating endothelial MP production.

Figure 3.

Immunodepletion or inhibition of HMGB1 abolishes the endothelial MP-stimulating activity in hypoxic trophoblast conditioned medium. A, HUVECs were incubated with the conditioned medium (CM) from JEG-3 cells cultured under normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). In parallel, the CM from hypoxic trophoblasts was incubated with an anti-HMGB1 antibody (Hmgb1 Ab) or a control IgG before being added to HUVECs. Endothelial MP production was analyzed by flow cytometry. B, In similar experiments, the CM from hypoxic trophoblasts was incubated with HMGB1 Box A fragment (2 μg/mL) or glycyrrhizin (GL) (200 μg/mL) before being added to HUVECs. Endothelial MP production was analyzed by flow cytometry. n=6 per group; Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and presented as mean ± SEM.

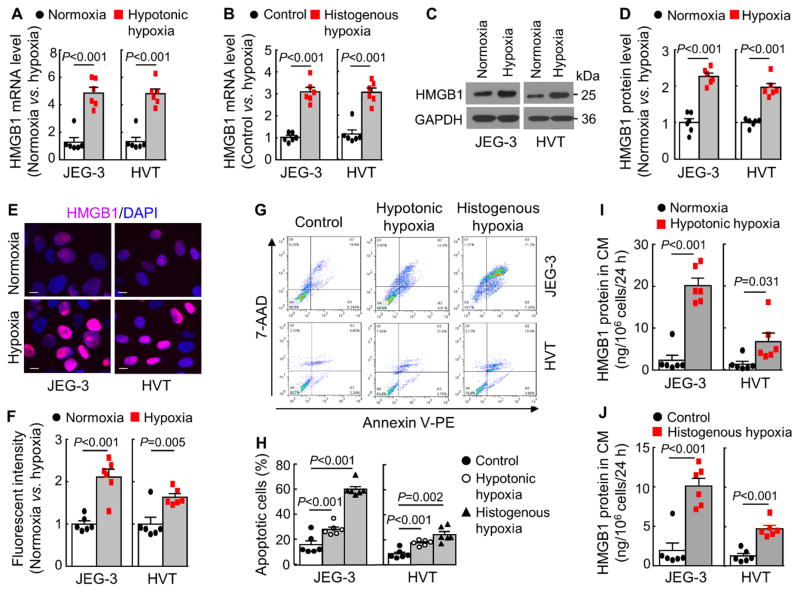

HMGB1 expression and release in hypoxic trophoblasts

We examined HMGB1 expression in JEG-3 cells under normoxia (20% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2). To ensure that findings reflect those of trophoblasts but not a particular cell line, we did similar experiments in primary human villous trophoblasts (HVTs). An ~4-fold increase in HMGB1 mRNA expression was found in hypoxic JEG-3 and HVT cells (Figure 4A). Similar results were found when the cells were treated with rotenone that caused histogenous hypoxia (Figure 4B). In Western blotting, HMGB1 protein levels were increased in hypoxic JEG-3 and HVT cells, compared with those in normoxic cells (Figure 4C and 4D). Immunostaining showed increased HMGB1 in hypoxic JEG-3 and HVT cell nuclei (Figure 4E and 4F). In flow cytometry, more apoptotic JEG-3 and HVT cells were found under hypotonic or histogenous hypoxia (Figure 4G and 4H). ELISA also detected high HMGB1 levels in the hypoxic JEG-3 and HVT cell conditioned media (Figure 4I and 4J). These results show that HMGB1 expression and release were increased in hypoxic trophoblasts in culture.

Figure 4.

HMGB1 expression and release in hypoxic trophoblasts. A, RT-PCR analysis of HMGB1 mRNA expression in JEG-3 and HVT cells cultured under normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). n=6 per group. Data (mean ± SEM) are fold changes vs. normoxic. B, RT-PCR analysis of HMGB1 mRNA expression in JEG-3 and HVT cells cultured without (control) or with rotenone (0.5 μmol/L) (histogenous hypoxia). n=6 per group. Data are mean ± SEM. C and D, Western blotting of HMGB1 protein in JEG-3 and HVT cells under normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). n=6 per group. Data in C are representative. The quantitative data (mean ± SEM; n=6) from densitometric analysis of Western blots are in D. E and F, HMGB1 staining in JEG-3 and HVT cells cultured under normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). Data in E are representative. Bar=10 μm. The fluorescent intensity was quantified in 5 random fields by Image J. The data (mean ± SEM) from 6 experiments are in F. G and H, Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in JEG-3 and HVT cells under normoxia (20% O2) (control) or hypoxia (1% O2) (hypotonic hypoxia) or without (control) or with rotenone (0.5 μmol/L) (histogenous hypoxia). 7-ADD−/annexin V+ and 7-ADD+/annexin V+ indicate early and late apopotic cells, respectively. Representative (G) and quantitative (mean ± SEM) (H) data are from 6 independent experiments. I and J, ELISA analysis of HMGB1 protein in the conditioned medium (CM) from JEG-3 and HVT cells under normoxia (20% O2) (control) or hypoxia (1% O2) (hypotonic hypoxia) or without (control) or with rotenone (0.5 μmol/L) (histogenous hypoxia). Data are mean ± SEM from 6 independent experiments analyzed by Student’s t-test.

Effects of rHMGB1 on HUVECs

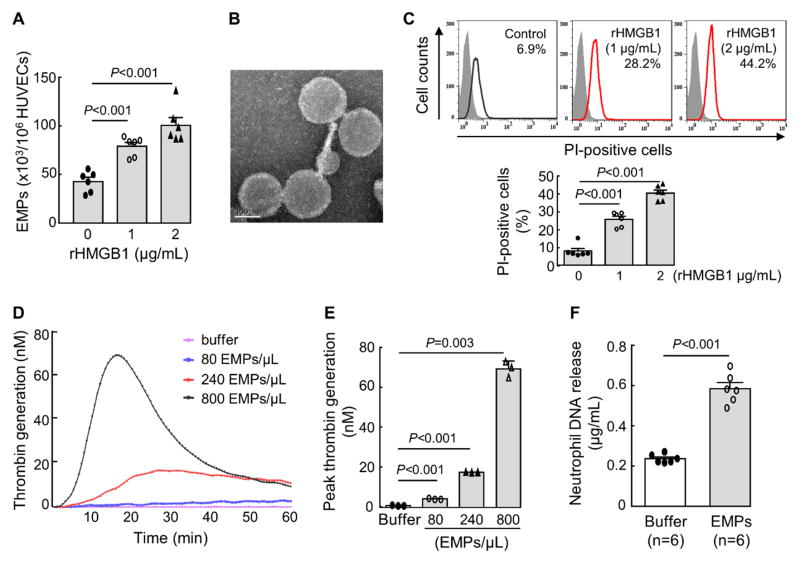

We treated HUVECs with purified human recombinant HMGB1 (rHMGB1) and detected increased MPs in the conditioned medium (Figure 5A). In electron microscopy, the MPs from rHMGB1-stimulated HUVECs were ~150–200 nm in diameter (Figure 5B), consistent with the size of MPs.14, 15 In flow cytometry, more propidium iodide-positive cells were found in rHMGB1-treated HUVECs (Figure 5C). These results indicate that rHMGB1 damaged HUVECs and increased the cell permeability and MP production.

Figure 5.

MP production and membrane permeability in rHMGB1-treated HUVECs. A, MP production in rHMGB1-treated HUVECs. Data (mean ± SEM) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA; n=6 per group. B, Electron microscopic analysis of MPs from rHMGB1-treated HUVECs. Bar=100 nm. C, Cell membrane permeability in rHMGB1-treated HUVECs analyzed by flow cytometry and propidium iodide (PI) staining. Percentages of PI-positive cells are indicated in top panels. Quantitative data (mean ± SEM) are shown in the lower graph. n=6 per group; Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. D and E, Effects of MPs from rHMGB1-treated HUVECs (EMPs) on thrombin generation in a human plasma-based assay, showing total (D) and peak (E) thrombin generation. In E, data are mean ± SEM; n=3 per group; Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. F, DNA release from isolated human neutrophils incubated with buffer or MPs from rHMGB1-treated HUVECs. Data are mean ± SEM; n=6 per group; Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test.

rHMGB1-stimulated endothelial MPs enhance blood coagulation and neutrophil activation

We examined the effect of rHMGB1-stimulated endothelial MPs on blood coagulation.42 The MPs from rHMGB1-stimulated HUVECs increased thrombin generation peaks and shortened peak formation times (Figure 5D and 5E). When the rHMGB1-stimulated endothelial MPs were incubated with isolated human neutrophils, higher levels of extracellular DNA were detected in the medium (Figure 5F), indicating that the endothelial MPs activated the neutrophils, inducing DNA release.

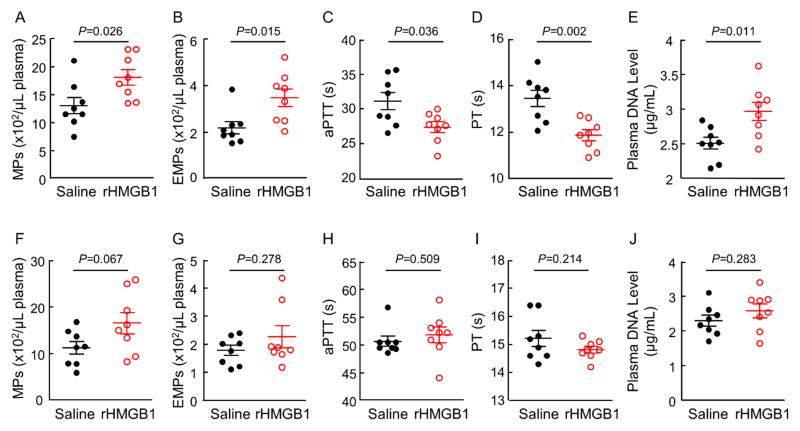

rHMGB1 increases circulating endothelial MPs, blood coagulation and plasma DNA levels in pregnant mice

To test the effect of HMGB1 in vivo, we intravenously injected rHMGB1 in pregnant and non-pregnant C57BL/6 mice. Compared with the saline control, rHMGB1 injection increased plasma total MPs and endothelial MPs (Figure 6A and 6B), shortened aPTT and PT (Figure 6C and 6D), and increased plasma DNA levels (Figurer 6E) in pregnant, but not non-pregnant (Figure 6F–6J), mice, indicating that rHMGB1 injection increased endothelial MP production and enhanced blood coagulation and neutrophil activation in pregnant, but not non-pregnant, mice.

Figure 6.

Effects of rHMGB1 injection on MP production, blood coagulation and plasma DNA levels in mice. rHMGB1 (50 μg in 200 μL saline) or equal volume of saline was injected intravenously in pregnant mice at day 18.5 p.c. (A to E) or age-matched non-pregnant mice (F to J). After 1.5 h, blood samples were collected. Total (A and F) and endothelial (B and G) MPs in plasma, blood clotting times (aPTT in C and H; PT in D and I), and plasma DNA levels (E and J) were analyzed. n=8 mice per group; Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test.

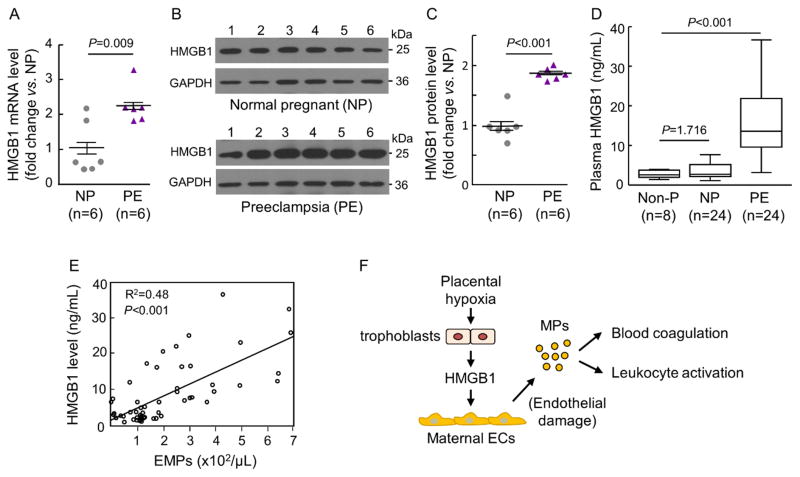

Placental and plasma HMGB1 levels in normal pregnant and PE women

We found an ~2-fold increase of placental HMGB1 mRNA (Figure 7A) and protein (Figure 7B and 7C) levels in PE women compared with those in normal pregnant women. ELISA showed higher plasma HMGB1 levels in PE women than those in non-pregnant and normal pregnant women (Figure 7D). There was a positive correlation between plasma HMGB1 and endothelial MP levels in non-pregnant, normal pregnant and PE women (Figure 7E). These results support the idea that placental hypoxia-induced HMGB1 expression and release from trophoblasts are an important mechanism in maternal endothelial damage and MP production, which enhances blood coagulation and leukocyte activation in PE (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

Placental HMGB1 expression and plasma HMGB1 levels in normal pregnant and PE women. A, RT-PCR analysis of placental HMGB1 mRNA expression in normal pregnant (NP) and PE women. Data (fold-change vs. NP) were analyzed by Student’s t-test. B and C, Western blotting of placental HMGB1 protein in NP and PE women. Data were normalzed to GAPDH levels. Quantitative data in C were analyzed by Student’s t-test. D, ELISA analysis of plasma HMGB1 levels in non-pregnant (Non-P), NP and PE women. Data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction. E, Correlation between plasma HMGB1 and endothelial MP (EMP) levels in Non-P, NP and PE women, as analyzed by the Pearson method. F, Proposed role of HMGB1 from hypoxic trophoblasts in causing maternal endothelial damage, producing endothelial MPs, and promoting blood coagulation and leukocyte activation in PE.

Discussion

PE is associated with high levels of circulating MPs,14, 16–19 which may come from endothelial cells, platelets, leukocytes and trophoblasts. In this study, we found that the increased plasma MPs in PE women were mostly of endothelial origin. Unlike in other thrombotic disorders,46, 47 platelet-derived MPs were not increased in PE women. Trophoblast-derived MPs were also higher in PE women, but the levels were ~6-fold less than that of endothelial MPs. Trophoblasts are a major cell type in the placenta. Our results indicate that the increased endothelial MPs are likely of maternal, but not placental, origin. MPs are pro-coagulant.13–15 In our study, circulating endothelial MP levels correlated with shortened prothrombin time, increased plasma fibrinogen d-dimer and decreased ATIII levels in PE women. We also found that PE women had high levels of tissue factor-positive MPs (Supplemental Figure III). These results are consistent with endothelial damage and enhanced blood coagulation in PE.11, 48, 49

Placental hypoxia plays a key role in PE.1, 2, 4–6 Using an unbiased proteomic approach, we identified HMGB1 as a primary protein in the hypoxic trophoblast conditioned medium that stimulated HUVEC MPs. This conclusion was supported by multiple lines of evidence. First, immunodepletion of HMGB1 from the hypoxic trophoblast medium inhibited the endothelial MP-stimulating activity. Second, incubation of HMGB1 Box A, an N-terminal HMGB1 fragment that antagonizes HMGB1 activity,44, 50 abolished the endothelial MP-stimulating activity from hypoxic trophoblasts. Third, a similar inhibitory effect was observed with glycyrrhizin, a natural compound that binds to and inhibits HMGB1.45, 50 Moreover, purified rHMGB1 stimulated MP production in HUVECs and the MPs from rHMGB1-stimulated HUVECs enhanced thrombin generation and induced neutrophil activation in vitro. These results indicate that HMGB1 from hypoxic trophoblasts is an important contributing factor in maternal endothelial damage and MP production, which in turn promotes blood coagulation and neutrophil activation in PE.

Oxidative stress and hypoxia are triggers for HMGB1 expression and release.51–53 We found up-regulated HMGB1 mRNA and protein expression in human trophoblasts cultured under hypotonic or histogenous hypoxia. We also detected increased apoptosis and HMGB1 release in similarly treated trophoblasts, indicating that HMGB1 up-regulation and release are part of stress responses in hypoxic trophoblasts. Consistently, we found high levels of HMGB1 mRNA and protein in placentae from PE women. Moreover, elevated plasma HMGB1 levels correlated with increased plasma endothelial MPs in these individuals. Our results are in agreement with previous reports of HMGB1 up-regulation in hypoxic trophoblasts in culture and high HMGB1 expression in placentae and sera from PE women.31–34, 36, 54 HMGB1 is expressed in many cell types. Our findings of up-regulated HMGB1 expression in trophoblasts do not exclude the possibility that other cells may also contribute to the elevated plasma HMGB1 in PE.

Placental hypoxia elicits a variety of cellular and inflammatory responses in PE, elevating circulating levels of many pro-inflammatory factors.54 Is increased HMGB1 sufficient for promoting maternal endothelial MP production, blood coagulation and neutrophil activation in pregnancy? In rHMGB1-injected pregnant mice, we observed increased plasma endothelial MPs and blood coagulation. We also detected increased plasma DNA levels, indicating neutrophil activation and NETosis in vivo. These results show that elevated circulating HMGB1 is sufficient to promote maternal endothelial MP production and hypercoagulability in pregnant mice. Interestingly, similar rHMGB1 injection in non-pregnant female mice did not significantly alter plasma endothelial MP levels, blood clotting times and plasma DNA levels, indicating that endothelial cells in non-pregnant mice are less sensitive to HMGB1 stimulation and that rHMGB1, at the dose tested, is insufficient to directly enhance blood coagulation and neutrophil activation in non-pregnant mice. Possibly, endothelial cells undergo phenotypic changes during pregnancy and become more susceptible to HMGB1-mediated damage. Alternatively, additional factor(s) from the pregnant uterus and/or the placenta act synergistically with HMGB1 to stimulate endothelial MP production. Further studies to examine the different HMGB1 responses in non-pregnant and pregnant mice will be important for understanding the role of HMGB1 in the pathophysiology of PE.

In summary, thrombophilia is a major complication in PE, a disease associated with placental hypoxia and trophoblast inflammation. In this study, we examined molecular mechanisms connecting placental hypoxia and thrombophilia in PE. Our results indicate that increased HMGB1 expression and release from hypoxic trophoblasts play an important role in promoting endothelial MP production, blood coagulation and neutrophil activation, thereby contributing to thrombophilia. It should be pointed out that PE is a multifactorial disease. Many factors are expected to contribute to the PE-associated phenotype. Our findings should encourage more studies to define the role of HMGB1 in PE-related hypercoagulability and to test if HMGB1 inhibition could be a therapeutic approach to reduce the thrombotic risk in PE.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HMGB1 is identified as a primary protein from hypoxic trophoblasts that stimulates endothelial MP production.

In PE, placental hypoxia-induced HMGB1 expression and release increase circulating endothelial MPs and contribute to thrombophilia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aizhen Yang for assistance in the thrombin assay and Lan Dai for assistance in MP detection experiments.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (91639116, 81671485, 81503304 and 81370718), the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB943302), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutes, and the NIH (R01 HD064634 and HL126697).

Abbreviations

- aPTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- ATIII

anti-thrombin III

- HMGB1

high-mobility group box 1

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- HVT

human villous trophoblast

- MP

microparticle

- PE

preeclampsia

- PT

prothrombin time

- rHMGB1

recombinant HMGB1

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Chaiworapongsa T, Chaemsaithong P, Yeo L, Romero R. Pre-eclampsia part 1: current understanding of its pathophysiology. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:466–80. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010;376:631–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui Y, Wang W, Dong N, et al. Role of corin in trophoblast invasion and uterine spiral artery remodelling in pregnancy. Nature. 2012;484:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher SJ. Why is placentation abnormal in preeclampsia? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:S115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science. 2005;308:1592–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1111726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts JM, Cooper DW. Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2001;357:53–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadroy Y, Grandjean H, Pichon J, Desprats R, Berrebi A, Fournie A, Boneu B. Evaluation of six markers of haemostatic system in normal pregnancy and pregnancy complicated by hypertension or pre-eclampsia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:416–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark P, Brennand J, Conkie JA, McCall F, Greer IA, Walker ID. Activated protein C sensitivity, protein C, protein S and coagulation in normal pregnancy. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:1166–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Moerloose P, Amiral J, Vissac AM, Reber G. Longitudinal study on activated factors XII and VII levels during normal pregnancy. Br J Haematol. 1998;100:40–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George JN. The association of pregnancy with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10:339–44. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200309000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Middeldorp S. Anticoagulation in pregnancy complications. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014:393–9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stirling Y, Woolf L, North WR, Seghatchian MJ, Meade TW. Haemostasis in normal pregnancy. Thromb Haemost. 1984;52:176–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn YS. Cell-derived microparticles: ‘Miniature envoys with many faces’. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:884–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alijotas-Reig J, Palacio-Garcia C, Llurba E, Vilardell-Tarres M. Cell-derived microparticles and vascular pregnancy complications: a systematic and comprehensive review. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:441–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccin A, Murphy WG, Smith OP. Circulating microparticles: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Blood Rev. 2007;21:157–71. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aharon A, Brenner B. Microparticles and pregnancy complications. Thromb Res. 2011;127(Suppl 3):S67–71. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(11)70019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goswami D, Tannetta DS, Magee LA, Fuchisawa A, Redman CW, Sargent IL, von Dadelszen P. Excess syncytiotrophoblast microparticle shedding is a feature of early-onset pre-eclampsia, but not normotensive intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 2006;27:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight M, Redman CW, Linton EA, Sargent IL. Shedding of syncytiotrophoblast microvilli into the maternal circulation in pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:632–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Circulating microparticles in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2008;29(Suppl A):S73–7. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohli S, Ranjan S, Hoffmann J, et al. Maternal extracellular vesicles and platelets promote preeclampsia via inflammasome activation in trophoblasts. Blood. 2016;128:2153–2164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-705434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sargent I. Microvesicles and pre-eclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2013;3:58. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tannetta DS, Hunt K, Jones CI, Davidson N, Coxon CH, Ferguson D, Redman CW, Gibbins JM, Sargent IL, Tucker KL. Syncytiotrophoblast Extracellular Vesicles from Pre-Eclampsia Placentas Differentially Affect Platelet Function. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Y, McIntosh JJ, Reese JA, Deford CC, Kremer Hovinga JA, Lammle B, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, Knudtson EJ, George JN. Pregnancy outcomes following recovery from acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2014;123:1674–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-538900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris HE, Andersson U, Pisetsky DS. HMGB1: a multifunctional alarmin driving autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:195–202. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu Y, Tang D, Kang R. Oxidative stress-mediated HMGB1 biology. Front Physiol. 2015;6:93. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiuza C, Bustin M, Talwar S, Tropea M, Gerstenberger E, Shelhamer JH, Suffredini AF. Inflammation-promoting activity of HMGB1 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood. 2003;101:2652–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palumbo R, Sampaolesi M, De Marchis F, Tonlorenzi R, Colombetti S, Mondino A, Cossu G, Bianchi ME. Extracellular HMGB1, a signal of tissue damage, induces mesoangioblast migration and proliferation. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:441–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maugeri N, Campana L, Gavina M, Covino C, De Metrio M, Panciroli C, Maiuri L, Maseri A, D’Angelo A, Bianchi ME, Rovere-Querini P, Manfredi AA. Activated platelets present high mobility group box 1 to neutrophils, inducing autophagy and promoting the extrusion of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:2074–88. doi: 10.1111/jth.12710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tadie JM, Bae HB, Jiang S, Park DW, Bell CP, Yang H, Pittet JF, Tracey K, Thannickal VJ, Abraham E, Zmijewski JW. HMGB1 promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation through interactions with Toll-like receptor 4. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304:L342–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00151.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogel S, Bodenstein R, Chen Q, et al. Platelet-derived HMGB1 is a critical mediator of thrombosis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4638–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI81660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Q, Yin YX, Wei J, Tong M, Shen F, Zhao M, Chamley L. Increased expression of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in the cytoplasm of placental syncytiotrophoblast from preeclamptic placentae. Cytokine. 2016;85:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmlund U, Wahamaa H, Bachmayer N, Bremme K, Sverremark-Ekstrom E, Palmblad K. The novel inflammatory cytokine high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) is expressed by human term placenta. Immunology. 2007;122:430–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang B, Koga K, Osuga Y, Hirata T, Saito A, Yoshino O, Hirota Y, Harada M, Takemura Y, Fujii T, Taketani Y. High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) levels in the placenta and in serum in preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:143–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao X, Xiao F, Zhao M, Tong M, Wise MR, Stone PR, Chamley LW, Chen Q. Treating normal early gestation placentae with preeclamptic sera produces extracellular micro and nano vesicles that activate endothelial cells. J Reprod Immunol. 2017;120:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naruse K, Sado T, Noguchi T, Tsunemi T, Yoshida S, Akasaka J, Koike N, Oi H, Kobayashi H. Peripheral RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation endproducts)-ligands in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia: novel markers of inflammatory response. J Reprod Immunol. 2012;93:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang R, Cai J, Zhu Z, Chen D, Wang J, Wang Q, Teng Y, Huang Y, Tao M, Xia A, Xue M, Zhou S, Chen AF. Hypoxic trophoblast HMGB1 induces endothelial cell hyperpermeability via the TRL-4/caveolin-1 pathway. J Immunol. 2014;193:5000–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orozco AF, Lewis DE. Flow cytometric analysis of circulating microparticles in plasma. Cytometry A. 2010;77:502–14. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gnaiger E. Oxygen conformance of cellular respiration. A perspective of mitochondrial physiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;543:39–55. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8997-0_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S, Cao P, Dong N, et al. PCSK6-mediated corin activation is essential for normal blood pressure. Nat Med. 2015;21:1048–53. doi: 10.1038/nm.3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong N, Zhou T, Zhang Y, Liu M, Li H, Huang X, Liu Z, Wu Y, Fukuda K, Qin J, Wu Q. Corin mutations K317E and S472G from preeclamptic patients alter zymogen activation and cell surface targeting. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:17909–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.551424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z, Hu Y, Yan R, Dong L, Jiang Y, Zhou Z, Liu M, Zhou T, Dong N, Wu Q. The Transmembrane Serine Protease HAT-like 4 Is Important for Epidermal Barrier Function to Prevent Body Fluid Loss. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45262. doi: 10.1038/srep45262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou J, Wu Y, Wang L, Rauova L, Hayes VM, Poncz M, Essex DW. The disulfide isomerase ERp57 is required for fibrin deposition in vivo. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1890–7. doi: 10.1111/jth.12709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossi AG, Sawatzky DA, Walker A, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors enhance the resolution of inflammation by promoting inflammatory cell apoptosis. Nat Med. 2006;12:1056–64. doi: 10.1038/nm1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang H, Ochani M, Li J, et al. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434651100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mollica L, De Marchis F, Spitaleri A, Dallacosta C, Pennacchini D, Zamai M, Agresti A, Trisciuoglio L, Musco G, Bianchi ME. Glycyrrhizin binds to high-mobility group box 1 protein and inhibits its cytokine activities. Chem Biol. 2007;14:431–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee YJ, Jy W, Horstman LL, Janania J, Reyes Y, Kelley RE, Ahn YS. Elevated platelet microparticles in transient ischemic attacks, lacunar infarcts, and multiinfarct dementias. Thromb Res. 1993;72:295–304. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90138-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rectenwald JE, Myers DD, Jr, Hawley AE, Longo C, Henke PK, Guire KE, Schmaier AH, Wakefield TW. D-dimer, P-selectin, and microparticles: novel markers to predict deep venous thrombosis. A pilot study. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:1312–7. doi: 10.1160/TH05-06-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chambers JC, Fusi L, Malik IS, Haskard DO, De Swiet M, Kooner JS. Association of maternal endothelial dysfunction with preeclampsia. JAMA. 2001;285:1607–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goulopoulou S, Davidge ST. Molecular mechanisms of maternal vascular dysfunction in preeclampsia. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sitia G, Iannacone M, Muller S, Bianchi ME, Guidotti LG. Treatment with HMGB1 inhibitors diminishes CTL-induced liver disease in HBV transgenic mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:100–7. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bauer EM, Shapiro R, Zheng H, Ahmad F, Ishizawar D, Comhair SA, Erzurum SC, Billiar TR, Bauer PM. High mobility group box 1 contributes to the pathogenesis of experimental pulmonary hypertension via activation of Toll-like receptor 4. Mol Med. 2012;18:1509–18. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamada T, Torikai M, Kuwazuru A, et al. Extracellular high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 is a coupling factor for hypoxia and inflammation in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2675–85. doi: 10.1002/art.23729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang D, Kang R, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Lotze MT. High-mobility group box 1, oxidative stress, and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1315–35. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nadeau-Vallee M, Obari D, Palacios J, Brien ME, Duval C, Chemtob S, Girard S. Sterile inflammation and pregnancy complications: a review. Reproduction. 2016;152:R277–R292. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.