Abstract

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is classically considered an illness of severely immunocompromised patients with limited host defenses. However, IPA has been reported in immunocompetent but critically ill patients. This report describes two fatal cases of pathologically confirmed IPA in patients with Influenza in the intensive care unit. One patient had Influenza B infection, whereas the other had Influenza A H1N1. Both patients died despite broad-spectrum antimicrobials, mechanical ventilation, and vasopressor support. Microscopic and histologic postmortem examination confirmed IPA. Review of the English language and foreign literature indicates that galactomannan antigen testing and classic radiologic findings for IPA may not be reliable in immunocompetent patients. Respiratory cultures which grow Aspergillus species in critically ill patients, particularly those with underlying Influenza infection, should not necessarily be disregarded as contaminants or colonizers. Further research is needed to better understand the immunological relationship between Influenza and IPA for improved prevention and treatment of Influenza and Aspergillus co-infections.

Keywords: Aspergillus, Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, Influenza

1. Introduction

Aspergillus, a filamentous fungus commonly found in the environment and in healthcare settings, is transmitted to susceptible hosts via dispersion of conidia in the air. The great majority of people do not develop illness from Aspergillus despite daily inhalation of conidia. With constant exposure to Aspergillus, the normal human immune system has developed defenses for fungal clearance via alveolar macrophages, neutrophils, monocytes, and natural killer cells (Morrison et al., 2003; Schaffner et al., 1982; Stevens, 2006).

Classically, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) has been considered an illness of severely immunocompromised patients with limited host defenses, including those with solid organ transplants, hematologic malignancies, and neutropenia. Case reports have also described IPA in immunocompetent but critically ill patients with risk factors such as cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic alcohol abuse, burn injury, diabetes, malnutrition, and Influenza infection (Bagdasarian, 2012; Carfagna et al., 2011; Clancy and Nguyen, 1998; Guinea et al., 2010; Hovenden et al., 1991; Janes et al., 1998; Karam and Griffin, 1986; Komase et al., 2007; Samarakoon and Soubani, 2008; Sridhar et al., 2012; Stevens and Melikian, 2011). Our report describes two fatal cases of pathologically confirmed invasive aspergillosis in immunocompetent patients with Influenza in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting, and details and summarizes the relevant literature.

2. Methods

We reviewed the literature on invasive aspergillosis and Influenza co-infection in immunocompetent patients. Immunocompetency was defined as patients without neutropenia, solid organ transplants, HIV/AIDS, congenital immunodeficiencies, and hematologic malignancies. References were identified using PubMed searches with the search terms “aspergillus,” “aspergillosis,” “Influenza,” “H1N1,” and “invasive aspergillosis.” Publications from January 1950 through November 2017 were included. Relevant articles were also identified using Google Scholar. Articles resulting from these searches and relevant references cited in those articles were reviewed for inclusion. Foreign language articles were also included when translation was available. When available, we abstracted age, gender, comorbidities, Influenza serology, and classification of invasive aspergillosis based on the modified European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Mycosis Study Group (EORTC/MSG) criteria.

2.1. Patient 1

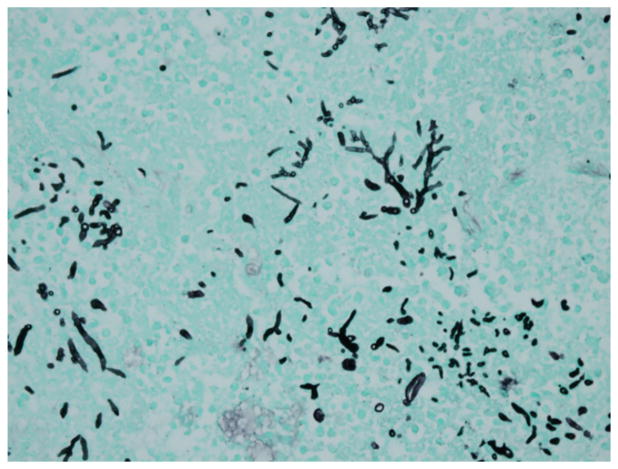

A 56-year-old Filipino-American man with a history of poorly controlled diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia on no medications presented to Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (San Jose, CA) with 1 month of fatigue and polydipsia and 3 days of nonproductive cough. His presenting vital signs were: heart rate 116 beats/min, respiratory rate 32 breaths/min, blood pressure 174/95 mm Hg, temperature 37.7 °C, and oxygen saturation 88% on 4 L/min of supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula. His initial venous blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.24, pCO2 30 mm Hg, and pO2 of 39 mm Hg. In the emergency department (ED), he was diagnosed with hypoxic respiratory failure requiring immediate tracheal intubation. He was also in diabetic ketoacidosis and septic shock from multilobar pneumonia. On hospital day (HD) 2, he had ST-elevation electrocardiogram changes likely from pericarditis as subsequent left ventricular catheterization revealed no coronary obstruction. Sputum PCR on admission was positive for Influenza B, and he received a 5-day course of oseltamivir. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan on HD 6 showed bibasilar consolidations with cystic changes in the right upper lobe. He continued to require vasopressors and ventilator support during his admission. The patient was also started on broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, including vancomycin, meropenem, and ciprofloxacin. Two blood cultures and sputum culture obtained on admission returned positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Repeat surveillance blood cultures were negative. Acid-fast bacilli sputum smear and cultures were negative. On HD 19 and HD 22, the endotracheal aspirate had light growth of Aspergillus fumigatus. Bronchoscopy was performed on HD 23, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) had light growth of A. fumigatus. BAL galactomannan antigen was elevated to >9.99 (reference range <0.50, Quest Diagnostics). Voriconazole was started on HD 24. The patient developed oliguric renal failure and started hemodialysis on HD 25. He did not receive steroids during his admission. Inhaled nitric oxide therapy was implemented for severe hypoxemia, but his clinical status continued to decline despite maximal vasopressor and ventilatory support. The patient died on HD 29, and postmortem examination showed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis on histologic examination (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient 1: Gomori’s methenamine stain (GMS) from postmortem exam showing fungal tissue invasion.

2.2. Patient 2

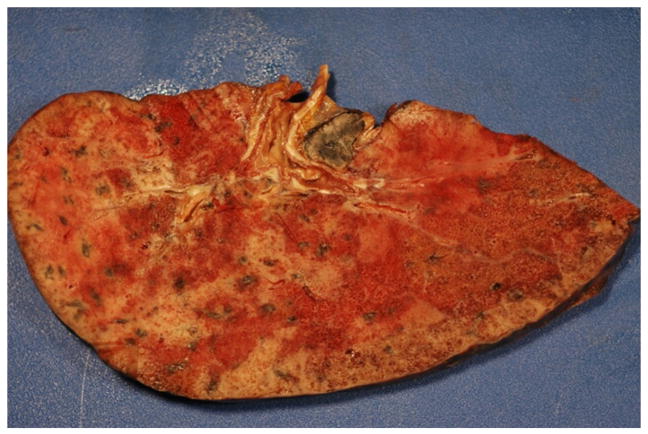

A 67-year-old Hispanic man, with history of hypertension, presented to Santa Clara Valley Medical Center with 2 weeks of productive cough and fever. He was a construction worker (cement finishing) who had emigrated from Mexico many years prior to admission. His only prescribed outpatient medication was atenolol, which he was not taking regularly. Two days prior to admission, the patient presented to an urgent care center with complaint of cough, and he was prescribed azithromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and a 6-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg. He likely took 60 mg of prednisone 2 days prior to admission and 50 mg of prednisone 1 day prior to admission. In the ED, the patient had a body temperature of 36.2 °C, blood pressure of 135/86 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, pulse of 83 beats/min, and an oxygen saturation of 88% while breathing air. His initial arterial blood gas analysis was notable for a pH of 7.42, pCO2 of 29 mm Hg, and pO2 of 76 mm Hg on 15 L/min of supplemental oxygen by face mask. He was transferred to the ICU for closer monitoring and subsequently required intubation on HD 4 for refractory hypoxia despite non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. Sputum PCR was positive for Influenza A H1N1 on admission, and oseltamivir was started. The patient received oseltamivir throughout his hospitalization, and the dose was adjusted when he developed worsening renal failure. He did not receive steroids during his admission. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started including vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and meropenem. A chest CT scan on HD 1 showed diffuse ground-glass opacities and an 8-mm right upper lobe nodule. On HD 5, an endotracheal aspirate had light growth of A. fumigatus. Intravenous voriconazole was started for presumed pulmonary aspergillosis on HD 9. Of note, on HD 5, the serum cryptococcal antigen test was reported positive with a titer of 1:2 (Quest Diagnostics) and fluconazole was started. Repeat serum cryptococcal antigen was negative on HD 11, and the initial result was believed to be a false positive. Serum galactomannan antigen was negative on HD 8. The patient developed oliguric renal failure requiring hemodialysis starting on HD 8. His clinical course worsened with multiorgan failure on maximal medical therapy, and on HD 23, the patient died from respiratory failure. Postmortem examination showed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis confirmed by histological studies (gross specimen shown in Fig. 2). There was no evidence of cryptococcosis on pathology.

Fig. 2.

Patient 2: gross postmortem lung specimen with fungal invasion.

3. Results

Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of case reports of immunocompetent patients with Influenza and invasive aspergillosis, with immunocompetency defined as patients without neutropenia, solid organ transplants, HIV/AIDS, congenital immunodeficiencies, and hematologic malignancies. There were 36 patients identified (15 female, 22 male), and 26 (72%) died. Of the patients who died, 21 (81%) received antifungal therapy. There were 22 cases (61%) of proven IPA based on biopsy findings. Influenza A was confirmed in 27 patients, influenza B in 7 patients, and Influenza was not serologically confirmed in 2 patients. In our review, there were 11 cases of IPA associated with H1N1 Influenza, and 7 of these patients died. Tobacco use was reported in 5 (14%) patients, alcohol abuse in 4 (11%) patients, and diabetes in 4 (11%) patients. Twelve patients (33%) in our review received steroids, with only 3 of these patients surviving.

Table 1.

Case reports of Influenza and invasive Aspergillus co-infection in immunocompetent patients

| Year of publication |

Author | N | Age/sex | Comorbidities | Viral serology |

Proven IPAb |

Mycologic basis of IPA diagnosis |

Steroids | Antifungal therapy reported? |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Abbott et al., 1952a | 1 | 51/F: housewife | None | None | Yes | Postmortem | No | None | Died |

| 1979 | Fischer and Walker, 1979 | 2 | 59/F | None | Influenza A | Yes | Postmortem | No | None | Died |

| 47/F | None | Influenza A | Yes | Postmortem | No | None | Died | |||

| 1980 | Jariwalla et al., 1980a | 1 | 14/F: student | None | None | Yes | Postmortem | Yes | None | Died |

| 1982 | McLeod et al., 1982 | 1 | 69/F housewife | None | Influenza A | No | Tracheal aspirate culture | No | Amphotericin B, Flucytosine, Econazole | Survived |

| 1983 | Horn et al., 1983 | 1 | 42/M | DM, HTN | Influenza A | Yes | Postmortem | No | None | Died |

| 1985 | Urban et al., 1985 | 1 | 72/M | Tobacco | Influenza A | Yes | Postmortem | Yes | Amphotericin B | Died |

| 1985 | Lewis et al., 1985 | 1 | 28/F: student/actress | None | Influenza A | Yes | Postmortem | Yes | Amphotericin B | Died |

| 1991 | Hovenden et al., 1991 | 1 | 61/M | Tobacco, PUD, ETOH | Influenza A | Yes | Postmortem | No | Clotrimoxazole, Amphotericin B | Died |

| 1992 | Kobayashi et al., 1992 | 1 | 49/M: ironworks manager | ETOH | Influenza A H3N2 | Yes | Postmortem | No | Miconazole, Amphotericin B, Fluconazole | Died |

| 1996 | Alba et al., 1996 | 1 | 58/M | Tobacco | Influenza A | Yes | Transthoracic needle aspirate/BAL culture | No | Amphotericin B | Survived |

| 1999 | Boots et al., 1999 | 1 | 35/F: nurse | None | Influenza A | Yes | Aspergillus niger on BAL culture and endobronchial biopsy | Yes | Amphotericin B (liposomal and inhaled), Flucytosine, Itraconazole | Survived |

| 1999 | Funabiki et al., 1999 | 1 | 83/M | Gastric Cancer (2C) dx age 70, third degree AV block | Influenza A | No | Serum and pleural fluid galactomannan antigen | No | Itraconazole, Amphotericin B | Died |

| 1999 | Vandenbos et al., 1755 | 1 | 89/F | HTN, heart failure | Influenza A | Yes | Postmortem | No | Itraconazole | Died |

| 2001 | Matsushima et al., 2001 | 1 | 55/M: arc welding | Pneumoconiosis | Influenza A | Yes | Postmortem | No | Fluconazole | Died |

| 2005 | Hasejima et al., 2005 | 1 | 63/F | Pulmonary TB age 7 | Influenza B | No | Sputum culture with Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus antibody | No | Itraconazole, Amphotericin B | Survived |

| 2010 | Lat et al., 2010 | 2 | 28/M: college student | None | Influenza A H1N1 | Yes | Bronchoscopic biopsy | Yes | Amphotericin B, Voriconazole, Micafungin | Died |

| 51/M: officer worker | None | Influenza A H1N1 | Yes | Postmortem | Yes | Fluconazole, Voriconazole | Died | |||

| 2011 | Adalja et al., 2011 | 3 | 52/M | GERD, HTN | Influenza A H1N1 | No | Bronchial plaque showing Aspergillus fumigatus | No | Fluconazole, Amphotericin B | Died |

| 48/M | None | Influenza A H1N1 | No | BAL culture with Aspergillus fumigatus | No | Voriconazole | Survived | |||

| 45/F | Mild, intermittent asthma | Influenza A H1N1 | Yes | VATS biopsy | No | Amphotericin B | Survived | |||

| 2011 | Kim et al., 2012 | 1 | 67/M | ETOH, Hepatitis C | Influenza A H1N1 | No | Serum and BAL galactomannan antigen | Yes | Voriconazole | Died |

| 2012 | Bagdasarian, 2012 | 1 | 58/F | Mild asthma | Influenza A H1N1 | Yes | Bronchoscopic biopsy | Yes (inhaled) | Voriconazole, Caspofungin, Micafungin, Amphotericin B | Survived |

| 2013 | Kwon et al., 2013 | 1 | 60/M | HTN | Influenza A | Yes | Bronchoscopic biopsy | No | Voriconazole | Survived |

| 2013 | Toh et al., 2013 | 1 | 63/F | DM | Influenza A | No | Endotracheal aspirate culture | Yes | Voriconazole | Died |

| 2014 | Park et al., 2014 | 1 | 55/M | Tobacco | Influenza B | No | BAL culture, serum galactomannan antigen | No | Voriconazole reported? | Died |

| 2016 | Pietsch et al., 2016 | 1 | 63/F | Hx of breast cancer, tobacco | Influenza A | Yes | Trans-bronchial biopsy | No | Antifungal given, not specified | Died |

| 2016 | Crum-Cianflone, 2016b | 5 | 47/M | RAD | Influenza A H1N1 | No | BAL culture, BAL galactomannan antigen | Yes | Voriconazole, Micafungin | Survived |

| 86/M | CKD, CHD | Influenza B | No | Respiratory culture | No | Voriconazole | Died | |||

| 57/M | DM, HTN | Influenza B | No | Respiratory culture | No | Voriconazole | Died | |||

| 59/M | ETOH | Influenza B | No | Respiratory culture | No | Voriconazole, Micafungin | Survived | |||

| 62/M | RAD, acute perforated duodenum | Influenza A H1N1 | No | Respiratory culture | No | Voriconazole | Died | |||

| 2017 | Nulens et al., 2017 | 1 | 51/F | None | Influenza B | Yes | Bronchoscopic biopsy | Yes | Voriconazole | Died |

| 2017 | Su and Yu, 2017 | 1 | 60/M | HTN | Influenza A H1N1 | No | Respiratory culture | Yes | Voriconazole | Died |

| 2017 | Current study | 2 | 56/M | DM, HTN | Influenza B | Yes | Postmortem | No | Voriconazole | Died |

| 47/F | HTN | Influenza A H1N1 | Yes | Postmortem | No | Voriconazole, Fluconazole | Died |

Note: Immunocompetency in this series is defined by the absence of neutropenia, solid organ transplants, HIV/AIDS, congenital immunodeficiencies, and hematologic malignancies. There were four larger case series which included immunocompetent patients with Influenza and IPA; however, these were not listed above as granular data were not available for individual patients (Ku et al., 2017; Martín-Loeches et al., 2011; van de Veerdonk et al., 2017; Wauters et al., 2012).

Abbreviations: IPA = invasive pulmonary aspergillosis; F = female; M = male; HTN = hypertension; PUD = peptic ulcer disease; DM = diabetes mellitus; ETOH = ethanol; TB = tuberculosis; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; VATS = video-assisted thorascopic surgery; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RAD = reactive airway disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; CHD = chronic heart disease.

Abbott et al. (1952) presume the patient had postInfluenza pneumonia during an Influenza epidemic, but no laboratory evidence was available. Jariwalla et al. (1980) also presume underlying Influenza pneumonia without serologic confirmation.

Based on EORTC/MSG criteria (De Pauw et al., 2008)

4. Discussion

Our two patients illustrate the importance of considering invasive aspergillosis in immunocompetent patients with underlying Influenza infection. Current definitions of IPA commonly used are based on the EORTC/MSG consensus group guidelines that categorize patients into proven, probable, and possible invasive fungal disease (De Pauw et al., 2008). Proven IPA is based on histopathological lung tissue examination, the gold standard of diagnosis. The definition of probable IPA requires host immunosuppression, specific radiographic signs, and mycological evidence such as culture or positive galactomannan. This classification is most relevant to severely immunocompromised patients but may not be entirely applicable to critically ill, immunocompetent patients in the ICU.

In the ICU setting, the significance of isolating Aspergillus from respiratory cultures of immunocompetent or mildly immunocompromised hosts can be unclear. Hence, an alternate definition for IPA in critically ill patients was proposed (Blot et al., 2012). IPA, as evidenced in our two patients, can occur in immunocompetent patients without classic risk factors including neutropenia, stem cell transplants, and T-cell immunosuppressant chemotherapy. The revised guidelines classify patients into proven IPA, putative IPA, and colonization only (Blot et al., 2012). The revised guidelines may be more inclusive of patients with IPA in the ICU setting with implications for earlier and more inclusive antifungal therapy. Putative IPA in the revised guidelines requires compatible signs and symptoms, abnormal lung imaging, and either immunosuppressed host factors or a positive BAL culture. Our first patient underwent bronchoscopy late in his course and met criteria for putative IPA prior to death given the BAL culture. Our second patient would not have been included in the putative IPA category as he never underwent biopsy or bronchoscopy due to clinical instability.

Galactomannan antigen testing is not included in the revised proposed criteria (Blot et al., 2012). This omission is due to poor sensitivity and specificity of serum galactomannan testing in immunocompetent hosts, particularly those nonneutropenic. BAL galactomannan testing is superior to serum testing but has only modest accuracy (Meersseman et al., 2008; Zou et al., 2012). A 2012 case report of two patients with pulmonary aspergillosis and 2009 H1N1 Influenza, including one immunocompetent host, showed that both patients had strongly positive galactomannan BAL results (Bagdasarian, 2012). Our first patient had a positive galactomannan antigen test from a BAL sample. The serum galactomannan test was negative in our second patient, and he never underwent bronchoscopy. In a study of 74 immunocompentent patients with pulmonary infiltrates, BAL galactomannan testing did not identify any cases of IPA not identified with BAL microscopy and culture (Nguyen et al., 2007). Additionally, patients given beta-lactam antibiotics, such as amoxicillin-clavulanate and piperacillin-tazobactam, may have falsely positive galactomannan antigen testing (Boonsarngsuk et al., 2010). Cross-reactivity with other fungi that have a cell-wall galactomannan similar to that of Aspergillus species can also cause positive results. In immunocompetent patients in the ICU, a negative galactomannan test should not be used to exclude IPA. A positive test should strongly prompt the use of antifungal therapy particularly in critically ill patients.

Both of our patients had abnormalities on CT chest imaging. The first patient had cystic upper lobe changes and bibasilar consolidations. The second patient had diffuse ground-glass opacities and an 8-mm right upper lobe nodule on CT imaging. Imaging can be useful in early diagnosis of IPA in neutropenic hosts. However, limited data are available regarding the usefulness of imaging in the diagnosis of IPA in immunocompetent hosts, and interpretation of imaging is further confounded by the presence of superinfections such as bacterial pneumonia in our first patient. The halo sign on CT scan is thought to be an early indicator of IPA in neutropenic hosts. The halo sign describes a macronodule (greater than or equal to 1 cm in diameter) surrounded by a ground-glass opacity. In a study of 235 patients with IPA, 95% had macronodules and 61% had halo signs. Consolidations (30%), infarct-shaped nodules (27%), cavitary lesions (20%), and air-crescent signs (10%) were also common (Greene et al., 2007). Neither of our patients had a halo sign on CT imaging.

Our experience suggests that respiratory cultures with Aspergillus species in critically ill patients, particularly those with underlying Influenza infection, should not necessarily be disregarded as contaminants or colonizers. A review of aspergillosis in non-neutropenic ICU patients concludes that mortality rates in this group may be higher than in immunocompromised patients with IPA (Bassetti et al., 2014). Of 11 immunocompetent patients with invasive aspergillosis and Influenza in a recent case series, 6 (55%) died (van de Veerdonk et al., 2017). Mortality differences were not observed in patients with and without hematologic malignancies in another review (Alshabani et al., 2015). In 1–2% of mechanically ventilated, non-neutropenic patients, respiratory cultures will show Aspergillus species. Of these, about 80% represent colonizers and 20% are believed to have IPA (Azoulay and Afessa, 2012).

Two systematic reviews of invasive aspergillosis complicated by Influenza infection reported 68 and 57 total cases (Alshabani et al., 2015; Crum-Cianflone, 2016a). One review of immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients with Influenza and IPA reported Influenza A in 93% of cases, with the majority of these having H1N1. H1N1 Influenza was associated with better outcomes than non-H1N1 Influenza (Alshabani et al., 2015). Our first patient had poorly controlled diabetes with diabetic ketoacidosis, a probable risk factor for IPA, but the second patient only had mild hypertension (Grizzanti and Knapp, 1981). Our second patient also had occupational exposures to cement which could be associated with structural lung disease and Aspergillus colonization. Of note, publication bias in any retrospective review is a limitation and may make outcomes appear more severe. Further prospective studies are needed.

Steroid therapy has been associated with poor outcomes in postInfluenza IPA (Alshabani et al., 2015). A retrospective review of 40 critically ill patients with H1N1 Influenza infection found that 23% developed IPA, with steroid administration being a significant risk factor (Wauters et al., 2012). Our second patient may have received 2 days of oral prednisone prior to admission, but neither patient received steroids during their hospital admission. Steroid use for patients with Influenza and acute respiratory distress syndrome is not beneficial (Brun-Buisson et al., 2011) and may be harmful. Aspergillus superinfection should be carefully considered in patients on steroids with severe Influenza infection.

Influenza infection likely preceded the development of invasive aspergillosis in our two patients. The median time of onset between Influenza infection and aspergillus infection is reported to be 5.5 days (range 5–29 days) (Alshabani et al., 2015). In the two patients presented here, the time between Influenza diagnosis and positive respiratory culture for aspergillus was 5 days and 19 days. Further research on the necessary start times for antifungal and antiviral therapy in patients with Influenza and IPA is needed.

A retrospective study found that when respiratory viruses are circulating, and in particular Influenza A, there is higher risk for IPA (Garcia-Vidal et al., 2014). Influenza may promote invasive aspergillosis via breakdown of bronchial mucosa, disruption of mucociliary clearance, and secretion of interleukins (Clancy and Nguyen, 1998; Garcia-Vidal et al., 2011). This may allow Aspergillus conidia to enter and infect the respiratory tract and bypass alveolar macrophages. Leukopenia, a predisposing mechanism for IPA susceptibility, was not observed in our two patients (Lat et al., 2010). Influenza is also thought to affect the Th1/Th2 balance (Rynda-Apple et al., 2015). This is a known critical determinant of patient outcomes in invasive aspergillosis. The normal host requires Th1 cells to battle Aspergillus, and antifungal therapy is associated with a switch to a Th1 profile (Cenci et al., 1999; Garcia-Vidal et al., 2013; Stevens, 2006). Th1 cells are also needed in host defenses against Influenza, and the Th1/Th2 balance likely plays a role in the susceptibility of patients to both Influenza and IPA including IPA in nonpulmonary sites (Kim et al., 2013). Further understanding of the immunological relationship between Influenza infection and IPA will be important for future prevention and management of these co-infections.

Abbreviations

- IPA

invasive pulmomary aspergillosis

- ICU

intensive care unit

Footnotes

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Abbott JD, Fernando HV, Gurling K, Meade BW. Pulmonary aspergillosis following post-Influenzal bronchopneumonia treated with antibiotics. Br Med J. 1952;1(4757):523–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4757.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adalja AA, Sappington PL, Harris SP, et al. Isolation of Aspergillus in three 2009 H1N1 influenza patients. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2011;5(4):225–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba D, Gomez-Cerezo J, Cobo J, Ripoll MM, Molina F, Vazquez JJ. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis associated with Influenza virus. An Med Interna. 1996;13(1):34–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshabani K, Haq A, Miyakawa R, Palla M, Soubani AO. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with Influenza infection: report of two cases and systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2015;9(1):89–96. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2015.996132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E, Afessa B. Diagnostic criteria for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(1):8–10. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0761ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdasarian N. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with 2009 H1N1 Influenza infection. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2012;20(6):422–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti M, Righi E, De Pascale G, et al. How to manage aspergillosis in non-neutropenic intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):458. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0458-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blot SI, Taccone FS, Van den Abeele AM, et al. A clinical algorithm to diagnose invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(1):56–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-1978OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonsarngsuk V, Niyompattama A, Teosirimongkol C, Sriwanichrak K. False-positive serum and bronchoalveolar lavage Aspergillus galactomannan assays caused by different antibiotics. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42(6–7):461–8. doi: 10.3109/00365541003602064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boots RJ, Paterson DL, Allworth AM, Faoagali JL. Successful treatment of post-Influenza pseudomembranous necrotising bronchial aspergillosis with liposomal amphotericin, inhaled amphotericin B, gamma interferon and GM-CSF. Thorax. 1999;54(11):1047–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.11.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun-Buisson C, Richard JC, Mercat A, Thiebaut AC, Brochard L Group R-SAHNvR. Early corticosteroids in severe Influenza A/H1N1 pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(9):1200–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0135OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carfagna P, Brandimarte F, Caccese R, Campagna D, Brandimarte C, Venditti M. Occurrence of Influenza A(H1N1)v infection and concomitant invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mycoses. 2011;54(6):549–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2010.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci E, Mencacci A, Del Sero G, et al. Interleukin-4 causes susceptibility to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis through suppression of protective type I responses. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(6):1957–68. doi: 10.1086/315142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. Acute community-acquired pneumonia due to Aspergillus in presumably immunocompetent hosts: clues for recognition of a rare but fatal disease. Chest. 1998;114(2):629–34. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum-Cianflone NF. Invasive aspergillosis associated with severe Influenza infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016a;3(3):171. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum-Cianflone NF. Invasive aspergillosis associated with severe Influenza infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016b;3(3):ofw171. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(12):1813–21. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JJ, Walker DH. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis associated with Influenza. JAMA. 1979;241(14):1493–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki Y, Ishii K, Kusaka S, et al. Aspergillosis following Influenza A infection. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 1999;36(4):274–8. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.36.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Vidal C, Barba P, Arnan M, et al. Invasive aspergillosis complicating pandemic influenza A (H1N1) infection in severely immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(6):e16. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Vidal C, Viasus D, Carratala J. Pathogenesis of invasive fungal infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(3):270–6. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835fb920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Vidal C, Royo-Cebrecos C, Peghin M, et al. Environmental variables associated with an increased risk of invasive aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(11):O939–45. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RE, Schlamm HT, Oestmann JW, et al. Imaging findings in acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: clinical significance of the halo sign. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(3):373–9. doi: 10.1086/509917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grizzanti JN, Knapp A. Diabetic ketoacidosis and invasive aspergillosis. Lung. 1981;159(1):43–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02713896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinea J, Torres-Narbona M, Gijon P, et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(7):870–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasejima N, Yamato K, Takezawa S, Kobayashi H, Kadoyama C. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis associated with Influenza B. Respirology. 2005;10(1):116–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn CR, Wood NC, Hughes JA. Invasive aspergillosis following post-Influenzal pneumonia. Br J Dis Chest. 1983;77(4):407–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovenden JL, Nicklason F, Barnes RA. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in non-immunocompromised patients. BMJ. 1991;302(6776):583–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6776.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes SM, Barker KF, Mak V, Bell D. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in an insulin-dependent diabetic. Respir Med. 1998;92(7):972–5. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jariwalla AG, Smith AP, Melville-Jones G. Necrotising aspergillosis complicating fulminating viral pneumonia. Thorax. 1980;35(3):215–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.35.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam GH, Griffin FM. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in nonimmunocompromised, nonneutropenic hosts. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8(3):357–63. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Kim MN, Lee SO, et al. Fatal pandemic Influenza A/H1N1 infection complicated by probable invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2012;55(2):189–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Kim MK, Kang CK, et al. A case of acute cerebral aspergillosis complicating Influenza A/H1N1pdm 2009. Infect Chemother. 2013;45(2):225–9. doi: 10.3947/ic.2013.45.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi O, Sekiya M, Saitoh H. A case of invasive broncho-pulmonary aspergillosis associated with Influenza A (H3N2) infection. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;30(7):1338–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komase Y, Kunishima H, Yamaguchi H, Ikehara M, Yamamoto T, Shinagawa T. Rapidly progressive invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a diabetic man. J Infect Chemother. 2007;13(1):46–50. doi: 10.1007/s10156-006-0481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku YH, Chan KS, Yang CC, Tan CK, Chuang YC, Yu WL. Higher mortality of severe Influenza patients with probable aspergillosis than those with and without other coinfections. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017;116(9):660–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon OK, Lee MG, Kim HS, Park MS, Kwak KM, Park SY. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis after Influenza a infection in an immunocompetent patient. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2013;75(6):260–3. doi: 10.4046/trd.2013.75.6.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lat A, Bhadelia N, Miko B, Furuya EY, Thompson GR. Invasive aspergillosis after pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(6):971–3. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.100165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Kallenbach J, Ruff P, Zaltzman M, Abramowitz J, Zwi S. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis complicating Influenza A pneumonia in a previously healthy patient. Chest. 1985;87(5):691–3. doi: 10.1378/chest.87.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Loeches I, Sanchez-Corral A, Diaz E, et al. Community-acquired respiratory coinfection in critically ill patients with pandemic 2009 Influenza A(H1N1) virus. Chest. 2011;139(3):555–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima H, Takayanagi N, Ubukata M, Sugita Y, Kanazawa M, Kawabata Y. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis following Influenza A infection. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;39(9):672–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod DT, Milne LJ, Seaton A. Successful treatment of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis complicating Influenza A. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285(6349):1166–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6349.1166-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J, et al. Galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: a tool for diagnosing aspergillosis in intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):27–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-606OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison BE, Park SJ, Mooney JM, Mehrad B. Chemokine-mediated recruitment of NK cells is a critical host defense mechanism in invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1862–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI18125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MH, Jaber R, Leather HL, et al. Use of bronchoalveolar lavage to detect galactomannan for diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis among nonimmunocompromised hosts. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(9):2787–92. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00716-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nulens EF, Bourgeois MJ, Reynders MB. Post-Influenza aspergillosis, do not underestimate Influenza B. Infect Drug Resist. 2017;10:61–7. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S122390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DW, Yhi JY, Koo G, et al. Fatal clinical course of probable invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with Influenza B infection in an immunocompetent patient. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2014;77(3):141–4. doi: 10.4046/trd.2014.77.3.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch U, Muller-Hocker C, Enzler-Tschudy A, Filipovic M. Severe ARDS in a critically ill Influenza patient with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(10):1632–3. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4379-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynda-Apple A, Robinson KM, Alcorn JF. Influenza and bacterial superinfection: illuminating the immunologic mechanisms of disease. Infect Immun. 2015;83(10):3764–70. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00298-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarakoon P, Soubani A. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with COPD: a report of five cases and systematic review of the literature. Chron Respir Dis. 2008;5(1):19–27. doi: 10.1177/1479972307085637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner A, Douglas H, Braude A. Selective protection against conidia by mononuclear and against mycelia by polymorphonuclear phagocytes in resistance to Aspergillus. Observations on these two lines of defense in vivo and in vitro with human and mouse phagocytes. J Clin Invest. 1982;69(3):617–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI110489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar V, Rajagopalan N, Shivaprasad C, Patil M, Varghese J. Acute community acquired Aspergillus pneumonia in a presumed immunocompetent host. BMJ Case Rep. 2012:2012. doi: 10.1136/bcr.09.2011.4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens DA. Th1/Th2 in aspergillosis. Med Mycol. 2006;44(s1):229–35. doi: 10.1080/13693780600760773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens DA, Melikian GL. Aspergillosis in the ‘nonimmunocompromised’ host. Immunol Invest. 2011;40(7–8):751–66. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2011.614307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su PA, Yu WL. Failure of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to rescue acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by dual infection of Influenza A (H1N1) and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017;116(7):563–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh HS, Jiang MY, Tay HT. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in severe complicated Influenza A. J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112(12):810–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban P, Chevrolet JC, Schifferli J, Sauteur E, Cox J. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis associated with an acute Influenza virus infection. Rev Mal Respir. 1985;2(4):255–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Veerdonk FL, Kolwijck E, Lestrade PP, et al. Influenza-associated aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201612-2540LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbos F, Mondain-Miton V, Roger PM, Saint-Paul MC, Dellamonica P. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis during Influenza: a fortuitous association? Presse Med. 1999;28(32):1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wauters J, Baar I, Meersseman P, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is a frequent complication of critically ill H1N1 patients: a retrospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(11):1761–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2673-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou M, Tang L, Zhao S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of detecting galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosing invasive aspergillosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]