Abstract

Introduction

Surgical resection is the cornerstone of curative-intent therapy for patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HC). The role of vascular resection (VR) in the treatment of HC in western centres is not well defined.

Methods

Utilizing data from the U.S. Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium, patients were grouped into those who underwent resection for HC based on VR status: no VR, portal vein resection (PVR), or hepatic artery resection (HAR). Perioperative and long-term survival outcomes were analyzed.

Results

Between 1998–2015, 201 patients underwent resection for HC, of which 31 (15%) underwent VR: 19 patients (9%) underwent PVR alone and 12 patients (6%) underwent HAR either with (n = 2) or without PVR (n = 10). Patients selected for VR tended to be younger with higher stage disease. Rates of postoperative complications and 30-day mortality were similar when stratified by vascular resection status. On multivariate analysis, receipt of PVR or HAR did not significantly affect OS or RFS.

Conclusion

In a modern, multi-institutional cohort of patients undergoing curative-intent resection for HC, VR appears to be a safe procedure in a highly selected subset, although long-term survival outcomes appear equivalent. VR should be considered only in select patients based on tumor and patient characteristics.

Keywords: Hilar cholangiocarcinoma, vascular resection, survival

Introduction

In the United States, cholangiocarcinoma has a reported autopsy prevalence of 0.01 to 0.46% and an incidence of 1–2/100,000 population, although the incidence is much higher in Asia(Hemming et al. 2011; Khan et al. 2012; Brito et al. 2015). Surgical resection or transplant is the only potentially curative treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma(Rocha et al. 2010), however, the role of en bloc vascular resection remains controversial(Shaib and El-Serag 2004; Patel and Singh 2007). Therefore, the aim of the current study was to explore the safety and long-term outcomes of vascular resection during surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma using data from a large cohort of patients from the U.S. Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium.

Methods

The U.S. Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium (USEBMC) is a collaboration of 10 high-volume, academic institutions, and includes Emory University, Johns Hopkins University, New York University, The Ohio State University, Stanford University, University of Louisville, University of Wisconsin, Vanderbilt University, Wake Forest University, and Washington University in St. Louis. All patients at participating institutions with HC who underwent resection with curative intent from 1998 to 2015 and had long-term follow-up data, including vital status and recurrence status, were included. Exclusion criteria included planned palliative or noncurative resections (including bile duct resection only, missing data on vascular resection status, or incomplete follow-up data.

Standard demographic and clinicopathologic data were collected including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, comorbidities (including history of hypertension, diabetes, COPD, congestive heart failure, renal failure, chronic steroid use, and tobacco use), tumor-related signs and symptoms, type of surgery and tumor-specific characteristics. In particular, data were collected on presence of jaundice or ascites and preoperative biliary drainage. Data on treatment-related variables, such as type of surgery and receipt of lymphadenectomy and intraoperative estimated blood loss (EBL), were also collected. Pathology review was performed by experienced GI pathologists at each institution, and staging was assigned as per American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition guidelines(Edge and Compton 2010). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each institution prior to data collection.

Resection margin and nodal status were ascertained based on final pathologic assessment. Tumor-specific characteristics included median tumor size, location, Bismuth type, and presence of vascular or perineural invasion. Length of hospital stay (LOS), reoperation, 30-day perioperative complications, and mortality were obtained. Complications were categorized based on the Clavien-Dindo classification system(Clavien et al. 2009). Date of last follow-up and vital status were collected for all patients through December 31, 2015. Survival information was verified with the Social Security Death Index when necessary.

The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS). Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact test or χ2 test as appropriate, and continuous variables were compared using ANOVA. OS was measured from the time of resection to death or last follow-up. RFS was measured from time of resection to recurrence, death or last follow-up. Survival probabilities were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier and compared using the log-rank test. Prognostic factors for survival were evaluated using multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

A total of 201 patients in the U.S. Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium database who underwent potentially curative resection for HC and met inclusion criteria were identified. Seventy patients were excluded for undergoing palliative, non-curative intent procedures, including 51 who underwent bile resection alone, while 23 patients were excluded for missing vascular resection status and 11 were excluded for incomplete follow-up data. In assessing the cohort, 170 patients (85%) did not undergo vascular resection, while 19 patients (9%) underwent PVR alone, and 12 patients (6%) underwent HAR, including 2 patients who had both PVR and HAR. Clinicopathologic characteristics by VR status are presented in Table 1. Patients who underwent HAR were significantly more likely to have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy than those who did not undergo VR and those who underwent PVR (3/12 versus 6/170 and 1/19, respectively, p=0.002).

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic Variables Associated with Vascular Resection in 201 Patients After Curative Resection for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma1

| No Vascular Resection n=170 |

PV Resection n=19 |

HA Resection n=12 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n, %) | 101 (60) | 9 | 6 | 0.515 |

| Age (x, sd) | 66 (10) | 62 | 52 | p<0.001 |

| Race | 0.804 | |||

| White | 129 (78) | 15 | 10 | |

| Black | 12 (7) | 2 | 1 | |

| Asian | 13 (8) | 0 | 0 | |

| BMI (x, sd)2 | 26 (6) | 2 | 0 | |

| Functional Status3 | 26 | 26 | 0.108 | |

| Independent | 152 (99) | 0.367 | ||

| Partially Dependent | 2 (1) | 17 | 11 | |

| ASA class | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 2 (1) | .928 | ||

| 2 | 40 (28) | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 94 (67) | 7 | 3 | |

| 4 | 5 (4) | 10 | 5 | |

| Hypertension | 90 (55) | 1 | 0 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 12 | 10 | 0.060 | |

| Managed with Oral Medications | 14 (9) | 0.549 | ||

| Insulin-Dependent | 8 (5) | 1 | 2 | |

| Prior Cardiac Event | 23 (14) | 2 | 0 | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 2 (0) | 5 | 0 | 0.136 |

| Dyspnea | 4 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0.830 |

| Tobacco Use | 42 (26) | 0 | 0 | 0.687 |

| COPD | 9 (6) | 3 | 5 | 0.203 |

| Acute Kidney Injury | 2 (1) | 2 | 1 | 0.639 |

| Preoperative sepsis | 11 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0.830 |

| Preoperative jaundice | 133 (80) | 1 | 0 | 0.648 |

| Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis | 4 (3) | 15 | 11 | 0.592 |

| Ascites | 6 (4) | 0 | 1 | 0.310 |

| Preoperative stent placement | 0 | 1 | 0.435 | |

| Endoscopic stent only | 68 (41) | 0.142 | ||

| Percutaneous stent only | 35 (21) | 5 | 4 | |

| Both | 36 (21) | 7 | 5 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 6 (4) | 1 | 3 | 0.002 |

Fields with missing data may not add to 100 percent

BMI indicates body mass index; ASA class, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification.

Functional status: Independent, the patient does not require assistance from another person for activities of daily living. This includes a person who is able to function independent with prosthetics, equipment or devices. Partially dependent, the patient requires some assistance from another person for activities of daily living. This includes a person who utilizes prosthetics, equipment or devices but still requires some assistance from another person for activities of daily living.

Operative and pathologic are presented in Table 2A. Post-operative characteristics are presented in Table 2B. The overall 30-day mortality in this cohort was 8%, The overall incidence of experiencing any complication was 69%. There was no difference in the incidence of Clavien-Dindo Grade III or higher complications among the no VR, PVR, and HAR groups (109/179, 9/19, and 8/12, respectively, p = 0.524). Postoperative liver failure showed a trend towards higher rates in patients who received portal vein resection, although this did not reach statistical significance (7/170, 3/19 and 0/12, for no VR, PVR and HAR group respectively, p=0.119). Patients received adjuvant therapy at comparable rates amongst all three groups.

TABLE 2A.

Operative Characteristics Associated with Vascular Resection in 201 Patients After Curative Resection for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma1

| No Vascular Resection n=170 |

PV Resection n=19 |

HA Resection n=12 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative characteristics | ||||

| Diagnostic laparoscopy | 30 (18) | 3 | 2 | 0.974 |

| Resection type | 0.380 | |||

| Radical cholecystectomy (segments IVb+V) & portal lymph node dissection | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| Right hepatectomy & Bile duct resection | 27 (16) | 2 | 1 | |

| Left hepatectomy & Bile duct resection | 50 (30) | 4 | 6 | |

| Extended right hepatectomy & Bile duct resection | 35 (21) | 4 | 0 | |

| Extended left hepatectomy + Bile duct resection | 14 (8) | 2 | 3 | |

| Right trisectorectomy + Bile duct resection | 19 (11) | 5 | 1 | |

| Left Trisectorectomy + Bile Duct resection | 16 (10) | 2 | 0 | |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 3 (0) | 0 | 0 | |

| Caudate resection | 69 (41) | 13 | 8 | 0.022 |

| MIS Technique2 | 0.968 | |||

| Open | 167 (98) | 19 | 12 | |

| Laparoscopic | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Laparoscopic-converted-to-open | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Intraoperative Blood transfusion | 67 (43) | 9 | 5 | 0.787 |

| EBL (mL) (x, sd) | 1011 (1880) | 1020 (635) | 2100 (1890) | 0.349 |

| Extent of portal vein resection | ||||

| Partial | 14 | 2 | ||

| Complete | 5 | 0 | ||

| No-touch technique | 3 | |||

| Type of portal vein reconstruction | ||||

| Primary | 15 | 1 | ||

| Venous patch | 1 | 0 | ||

| Prosthetic patch | 1 | 0 | ||

| Prosthetic conduit | 2 | 0 | ||

| Extent of hepatic artery resection | ||||

| Right hepatic artery resection | 3 | |||

| Left hepatic artery resection | 4 | |||

| Hepatic artery reconstruction | ||||

| End to end anastao | 0 | |||

| Vein graft | 3 | |||

| R0 resection status | 0.912 | |||

| R0 | 119 (70) | 14 | 8 | |

| R1 | 51 (30) | 5 | 4 | |

| Intraoperative frozen section margin collection | 148 (88) | 18 | 10 | 0.579 |

| Frozen section margin positive | 48 (33) | 6 | 2 | 0.709 |

| Intraoperative drain placement | 157 (92) | 17 | 12 | 0.539 |

Fields with missing data may not add to 100 percent

MIS indicates minimally invasive surgery; EBL, estimated blood loss; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; PNI, perineural invasion

TABLE 2B.

Pathologic and Post-Operative Characteristics Associated with Vascular Resection in 201 Patients After Curative Resection for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma1

| No Vascular Resection n=170 |

PV Resection n=19 |

HA Resection n=12 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathologic Characterisctics | ||||

| Pathologic grade | 0.607 | |||

| 1 | 30 (19) | 3 | 4 | |

| 2 | 92 (58) | 12 | 5 | |

| 3 | 35 (11) | 1 | 3 | |

| 4 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Tumor stage | 0.006 | |||

| T1 | 15 (12) | 0 | 2 | |

| T2a | 36 (28) | 1 | 2 | |

| T2b | 57 (44) | 5 | 3 | |

| T3 | 20 (15) | 7 | 4 | |

| T4 | 2 (2) | 2 | 0 | |

| N2 nodes sampled | 27 (16) | 7 | 5 | 0.016 |

| Positive lymph nodes | 63 (41) | 5 | 2 | 0.176 |

| LVI | 53 (39) | 7 | 4 | 0.640 |

| PNI | 110 (77) | 15 | 7 | 0.664 |

| Postoperative Characteristics | ||||

| 30-day mortality | 12 (7) | 3 | 0 | 0.153 |

| Length of stay (days) (x, sd) | 15 (10) | 20 | 11 | p<0.001 |

| Readmission | 42 (36) | 4 | 4 | 0.738 |

| Adjuvant therapy | 79 (53) | 8 | 6 | 0.569 |

| Any complication | 114 (69) | 13 | 6 | 0.623 |

| Recurrence | 55 (35) | 9 | 6 | 0.278 |

| Recurrence Location | 0.203 | |||

| Local | 13 (8) | 4 | 2 | |

| Distant | 24 (14) | 5 | 4 | |

| Both | 15 (9) | 0 | 0 | |

Fields with missing data may not add to 100 percent

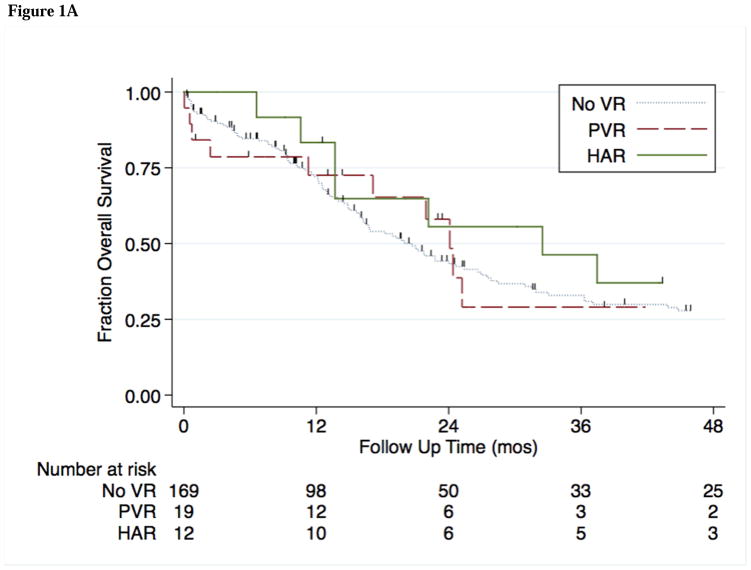

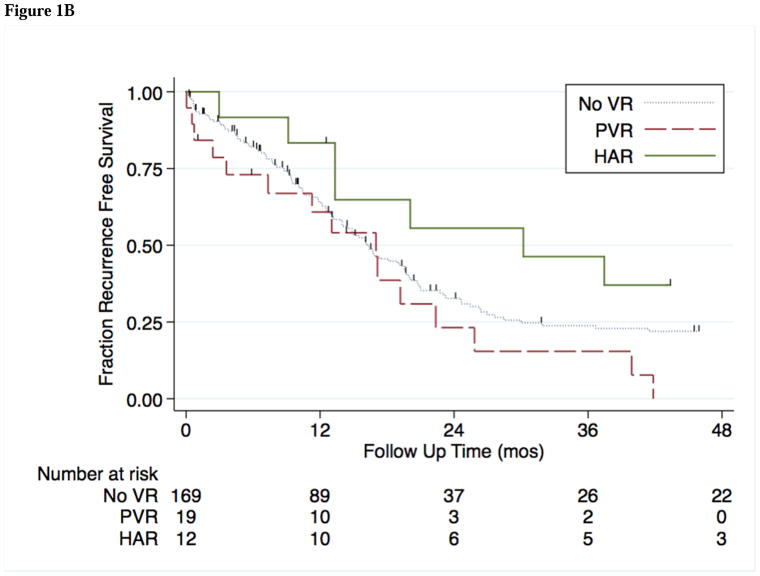

The median follow-up time in this cohort was 22 months, during which time 70 patients (41%) developed recurrence of disease. Median OS and RFS by potential prognostic factors are shown in Table 3A. Independent factors associated with OS and RFS are shown in Table 3B. Median OS was comparable among the no VR, PVR, and HAR groups (21, 24, and 33 months; p = 0.818) (Figure 1A). On univariate analysis, RFS was comparable between VR groups (16.2, 17.1 and 30.2 months for no VR, PVR and HAR respectively; p=0.199) (Figure 1B).

TABLE 3A.

Univariate Analysis of Variables Associated with OS and RFS After Curative Resection for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma

| N | Overall Survival

|

Recurrence Free Survival

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Survival (mo) | p value | Median Survival (mo) | p value | ||

| No vascular resection | 170 | 21 | 0.818 | 16 | 0.199 |

| Portal vein resection | 19 | 24 | 17 | ||

| Hepatic artery resection | 12 | 33 | 30 | ||

| Lymph node status | |||||

| Negative | 110 | 25 | 0.002 | 1935 | 0.004 |

| Positive | 70 | 16 | 11 | ||

| Age | |||||

| <60 years | 58 | 28 | 0.050 | 20 | 0.231 |

| >60 years | 142 | 18 | 16 | ||

| ASA class ≥3 | 52 | 24 | 0.954 | 15 | 0.623 |

| ASA class <3 | 148 | 20 | 17 | ||

| T stage | |||||

| T stage <3 | 211 | 22 | 0.002 | 19 | <0.001 |

| T stage ≥3 | 44 | 17 | 11 | ||

| Grade | |||||

| I | 37 | 32 | 0.136 | 22 | 0.05 |

| II | 108 | 19 | 16 | ||

| III | 39 | 23 | 13 | ||

| R0 resection status | |||||

| R0 | 92 | 23 | 0.291 | 17 | 0.518 |

| R1 | 39 | 19 | 15 | ||

ASA class, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification.

TABLE 3B.

Multivariate Cox Regression of Factors Associated with OS and RFS After Curative Resection for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma

| Overall Survival | Recurrence Free Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value |

|

|

|

|||||

| No vascular resection | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Portal vein resection | 0.9 | 0.5–2.2 | 0.993 | 1.7 | 0.8–3.3 | 0.138 |

| Hepatic artery resection | 1.0 | 0.5–2.2 | 0.964 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.3 | 0.176 |

| Age >60 | 1.3 | 0.8–2.2 | 0.273 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.7 | 0.777 |

| ASA class ≥3 | 0.8 | 0.6–1.2 | 0.328 | 0.7 | 0.4–1.1 | 0.099 |

| T stage ≥3 | 1.7 | 1.1–2.7 | 0.034 | 2.1 | 1.3–3.5 | 0.003 |

| Grade | ||||||

| I | Reference | Reference | ||||

| II | 1.1 | 0.7–1.8 | 0.676 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.7 | 0.735 |

| III | 1.2 | 0.8–2.1 | 0.590 | 1.7 | 1.1–2.9 | 0.030 |

| Margin status | ||||||

| R0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| R1 | 1.2 | 0.7–1.9 | 0.468 | 1.0 | 0.7–1.5 | 0.974 |

| Lymph node positive | 2.1 | 1.4–3.4 | 0.002 | 2.0 | 1.4–3.0 | <0.001 |

ASA class, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS for 201 patients who received no vascular resection (noVR), portal vein resection (PVR), or hepatic artery resection (HAR) during curative resection for HC.

Figure 1B. Kaplan-Meier estimates of RFS for 201 patients who received no vascular resection (noVR), portal vein resection (PVR), or hepatic artery resection (HAR) during curative resection for HC.

Discussion

In a large, modern, multi-institutional North American cohort of patients undergoing resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, vascular resection, including portal vein resection and/or hepatic artery resection, was performed in a select minority of younger patients with higher T stage disease. Both procedures were relatively safe in the perioperative period, and were associated with equivalent long-term survival outcomes when compared with patients who received no vascular resection, even when controlling for relevant clinical factors such as T stage and lymph node status. Vascular invasion remains a major obstacle in the treatment of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and traditionally invasion of vascular structure by tumor meant unresectable disease. However, with improvements in surgical technique and perioperative management, vascular resection and reconstruction in select patients who can tolerate the procedure offers an option for achieving R0 resection status and equivalent long-term survival(Matsuyama et al. 2016).

A major concern around vascular resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma is safety and feasibility of the procedure. In this cohort, patients who underwent vascular resection had combined characteristics of more advanced disease and younger age at operation, likely reflecting surgeon selection of patients most likely to both tolerate and benefit from the procedure. Patients who received vascular resection also tended to have lower ASA class, although this did not reach statistical significance. The overall complication rate was comparable to previously published series in hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Nuzzo et al. 2012; Loehrer et al. 2013; Shubert et al. 2014), and neither complication rates nor readmission rates differed significantly by VR group. Patients with PVR did show a higher average length of stay, and had a trend towards higher rates of postoperative liver failure. The overall mortality rate in this cohort was 9%, which is similar to the rate recently reported for mortality after resection for HC in the ACS NSQIP database (Loehrer et al. 2013), and differences in mortality rates between VR groups did not attain statistical significance. However, it should be noted that no perioperative deaths were seen in the HAR group, while 3 patients died in the PVR group, 2 of which experienced postoperative liver failure. While some prior series have argued that PVR is a safer operation while HAR should be regarded with caution (Miyazaki et al. 2007), the present data show that PVR yielded slightly worse perioperative outcomes, although the number of patients analyzed may be too small to detect true differences.

Previous reports have suggested that PVR may provide some survival benefit to patients undergoing curative resection for HC, while the impact of HAR on long-term survival remains largely unclear(Ebata et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2006; Miyazaki et al. 2007; Hemming et al. 2011; de Jong et al. 2012). Not surprisingly, patients who received VR with PVR or HAR had higher T stage tumors representing more advanced disease. Despite this, the rate of R0 resection amongst all three groups is uniform. This suggests that local control is achieved with vascular resection to at least the same extent as in patients who do not undergo vascular resection, a result similar to what has been previously reported in Asian cohorts (Matsuyama et al. 2016). This fact may be a strong driving factor behind equivalency in survival outcomes between all three groups, despite more advanced T stage disease in PVR and HAR groups.

This analysis suggests, at the least, that PVR in the treatment of HC is a safe option in an effort to achieve R0 margins during resection for HC, both with respect to perioperative morbidity and mortality, and long-term survival. However, it remains to be seen if PVR confers survival benefit to patients with locally invasive HC. Many previous studies assessing the role of vascular resection in HC report non-significant differences survival outcomes, often due to the relatively low number of patients available in the studies. In a 2007 retrospective, single-institution study, Miyazaki, et al. evaluated 228 patients with HC, of which 161 underwent curative-intent resection(Miyazaki et al. 2007). While a trend was seen towards decreasing survival with VR, there were no statistically significant differences between groups. Several subsequent single- or two-institution studies in Japan, China, and the USA have failed to discern any statistically significant differences in survival in HC patients receiving no VR, PVR, or HAR(Igami et al. 2010; Hemming et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2015; Matsuyama et al. 2016) (Table 4 for more detail). Despite the multi-institutional nature of the current dataset, hilar cholangiocarcinoma remains a rare disease entity, especially in the western hemisphere. It is interesting to note that despite the large centers included in this dataset, there were relatively small volumes of HC patients relative to Asian series and the rate of vascular resection was in general lower. Larger sample sizes may be necessary to fully understand if vascular resection confers a survival benefit in this patient population.

TABLE 4.

Studies evaluating vascular resection in curative-intent resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

| Investigator/ Year |

Country | Type Study | Years Data |

# HC/ # Resected |

5-year %OS no VR |

5-year %OS PVR |

5-Year %OS HAR |

5-Year %RFS no VR |

5-Year %RFS PVR |

5-Year %RFS HAR |

Conclusions: Improved Survival with Vasc Resection? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyazaki 2007 | Japan | Retrospective, single center | 1981–2004 | 228/161 | 30 | 16 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | No |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Igami 2010 | Japan | Retrospective, single center | 2001–2008 | 428/298 | 51 | 23 | 33 | NA | NA | NA | No |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Hemming 2011 | USA | Retrospective, single center | 1999–2010 | NA/95 | 45 | 43 | NA | NA | NA | NA | No |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Wang 2015 | China | Prospective, single center | 2005–2012 | 277/154 | 36 | 25 | 25 | NA | NA | NA | No |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Matsuyama 2016 | Japan | Retrospective, single center | 1992–2014 | 249/172 | NA | NA | NA | 46 | 51 | 22 | No |

This is the first multicenter study investigating the impact of vascular resection on outcomes for patients with HC in a North American population. However, as a retrospective analysis, it has several inherent limitations. Notably, the likely presence of confounding variables that were either not noted or not known at the time of data collection, despite the large number of variables collected, limits conclusions of causality. Furthermore, there is inherent preoperative selection bias based on patients and disease factors in comparing those that underwent VR to those who did not. Finally, as a retrospective database, some amount of data in each field collected was not able to be confirmed. However, it is expected that such missing data was random in nature and therefore would not be expected to affect the main findings of the current study. Additionally, despite the multi-institutional nature of this database and the large number of total patients reviewed, only a small number underwent vascular resection, making it difficult to make firm statistically significant conclusions. Despite these limitations, this study represents the largest, multi-institutional North American analysis of vascular resection in hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and as such provides valuable insights into variations in practice and outcomes after vascular resection.

In conclusion, in this multi-institutional analysis of 201 patients that underwent surgical resection for HC, vascular resection was performed in a small number of patients and was a safe procedure that yielded equivalent survival outcomes. This suggests that for select patients, in the hands of experienced surgeons at high-volume centers, vascular resection for HC is a safe tool for achieving R0 margins in an effort to improve survival. Surgeons should always consider individual patient and tumor characteristics when selecting patients for appropriate treatment for HC.

Footnotes

Selected for oral presentation at the AHPBA Annual Meeting 2017.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Works Cited

- Anderson CD, Pinson CW, Berlin J, Chari RS. The Oncologist. 1. Vol. 9. AlphaMed Press; 2004. Diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma; pp. 43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito AF, Abrantes AM, Encarnação JC, Tralhão JG, Botelho MF. Cholangiocarcinoma: from molecular biology to treatment. Med Oncol. 2015 Oct 1;32(11):245. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009 Aug;250(2):187–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MC, Marques H, Clary BM, Bauer TW, Marsh JW, Ribero D, et al. The impact of portal vein resection on outcomes for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis of 305 cases. Cancer. 2012 Oct 1;118(19):4737–47. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebata T, Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, Nagasaka T, Nimura Y. Hepatectomy with portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 52 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2003 Nov;238(5):720–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094437.68038.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge SB, Compton CC The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. Springer-Verlag. 2010 Jun;17(6):1471–4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemming AW, Mekeel K, Khanna A, Baquerizo A, Kim RD. Portal vein resection in management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2011 Apr;212(4):604–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.028. –discussion613–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano S, Kondo S, Tanaka E, Shichinohe T, Tsuchikawa T, Kato K, et al. Outcome of surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a special reference to postoperative morbidity and mortality. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences. 2010 Jul;17(4):455–62. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igami T, Nishio H, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Sugawara G, Nimura Y, et al. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the “new era”: the Nagoya University experience. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences. 2010 Jul 1;17(4):449–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin RD, Heaton N, Karani J, Pereira SP, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: an update. Gut. 2012;61:1657–69. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G-W, Kang JH, Kim H-G, Lee J-S, Lee J-S, Jang J-S. Combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin as first-line treatment for immunohistochemically proven cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006 Apr;29(2):127–31. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000203742.22828.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehrer AP, House MG, Nakeeb A, Kilbane EM, Pitt HA. Cholangiocarcinoma: are North American surgical outcomes optimal? J Am Coll Surg. 2013 Feb;216(2):192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama R, Mori R, Ota Y, Homma Y, Kumamoto T, Takeda K, et al. Significance of Vascular Resection and Reconstruction in Surgery for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: With Special Reference to Hepatic Arterial Resection and Reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Jul 7;23(S4):475–84. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki M, Kato A, Ito H, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Ohtsuka M, et al. Surgery. 5. Vol. 141. Elsevier; 2007. May, Combined vascular resection in operative resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: does it work or not; pp. 581–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz L, Roayaie S, Maman D, Fishbein T, Sheiner P, Emre S, et al. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2. Vol. 9. Springer-Verlag; 2002. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma involving the portal vein bifurcation: long-term results after resection; pp. 237–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Ardito F, Giovannini I, Aldrighetti L, Belli G, et al. Arch Surg. 1. Vol. 147. American Medical Association; 2012. Jan, Improvement in perioperative and long-term outcome after surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: results of an Italian multicenter analysis of 440 patients; pp. 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel T, Singh P. Cholangiocarcinoma: emerging approaches to a challenging cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007 May;23(3):317–23. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3280495451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha FG, Matsuo K, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences. 2010 Jul 1;17(4):490–6. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The Epidemiology of Cholangiocarcinoma. In: Berk PD, Gores G, editors. Seminars in Liver Disease. 02. Vol. 24. Copyright © 2004 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc; 333 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10001, USA: 2004. Jun 11, pp. 115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubert CR, Habermann EB, Truty MJ, Thomsen KM, Kendrick ML, Nagorney DM. Defining perioperative risk after hepatectomy based on diagnosis and extent of resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014 Nov;18(11):1917–28. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2634-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamoto E, Hirano S, Tsuchikawa T, Tanaka E, Miyamoto M, Matsumoto J, et al. Portal vein resection using the no-touch technique with a hepatectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB. 2014 Jan;16(1):56–61. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S-T, Shen S-L, Peng B-G, Hua Y-P, Chen B, Kuang M, et al. Combined vascular resection and analysis of prognostic factors for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HBPD INT. 2015 Dec;14(6):626–32. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(15)60025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]