Abstract

The dominant health delivery model for advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States, which focuses on provision of dialysis, is ill-equipped to address many of the needs of seriously ill patients. Although palliative care may address some of these gaps in care, its integration into advanced CKD care has been suboptimal due to several health system barriers. These barriers include uneven access to specialty palliative care services, under-developed models of care for seriously ill patients with advanced CKD, and misaligned policy incentives. This article reviews policies that affect the delivery of palliative care for this population, discusses reforms that could address disincentives to palliative care, identifies quality measurement issues for palliative care for individuals with advanced CKD and ESRD, and considers potential pitfalls in the implementation of new models of integrated palliative care. Reforming healthcare delivery in ways that remove policy disincentives to palliative care for patients with advanced CKD and ESRD will fill a critical gap in care.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease (CKD), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), palliative care, dialysis, health policy, quality of life, advance care planning, goals of care, patient-centered care

Introduction

The Medicare End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Program has long been at the forefront of innovations in healthcare payment and delivery models. While the program has achieved notable successes,1 the high cost of care and the perception that care is not patient-centered make the program a high-profile target for additional reforms. Foremost among the areas where the value of care is perceived to be low is among seriously ill patients -- including those with multi-morbidity, those with a high symptom burden, and those near the end of life.

The dominant healthcare delivery model for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) and ESRD focuses almost exclusively on optimizing provision of dialysis care, to the extent that patient needs beyond dialysis treatment have been largely neglected. This current dominant model is poorly equipped to help patients and families address the emotional and existential challenges of advanced illness and navigate complex treatment decisions, such as starting or stopping dialysis. More than a decade ago, the Institute of Medicine documented the consequences of failing to deliver “the right care to the right patient at the right time” in its landmark report “Crossing the Quality Chasm”.2 Many patients with advanced CKD and ESRD have wide-ranging unmet care needs, including a high burden of distressing symptoms and functional limitations.3 Although they receive high-cost, high-intensity care near the end of life, family members rate the quality of care that patients with ESRD receive at this time as poor.4,5

Better integration of palliative care into advanced CKD and dialysis care has been proposed to address the needs of these patients with multi-morbidity, high symptom burden, and limited life expectancy. 6,7 Palliative care refers to holistic medical, psychosocial and spiritual care for people with serious illness and was originally developed to address the needs of patients dying from cancer. With a focus on relief of symptoms and improving quality of life, palliative care is appropriate at any stage in a serious illness, including in conjunction with curative or life-extending treatment.3 Nephrology, along with other medical specialties, has lagged behind oncology in the adoption of palliative care.

In 2016, the National Institute on Aging and the National Palliative Care Research Center convened a workshop to identify palliative care research priorities in four subspecialty fields: CKD, heart disease, critical care, and surgery.8 In the context of the palliative care research agenda for CKD recently published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine,9 in this article we outline healthcare policies that shape delivery of care for patients with advanced CKD and ESRD, and suggest how healthcare delivery might be reformed to support a more patient-centered palliative approach to care for these seriously ill patients.

Policies that affect the care of patients with advanced CKD and ESRD

The policies that shape delivery of care for patients with ESRD originated from legislation extending Medicare eligibility to persons with ESRD in order to provide a much-needed funding mechanism for maintenance dialysis treatments. Unanticipated growth in the number of patients starting dialysis and increasing use of expensive injectable medications created cost pressures. In response, Medicare policies evolved over time with two overarching goals---restraining spending growth in the ESRD Program while simultaneously ensuring that patients receive outpatient dialysis care that meets quality standards (Table 1). To accomplish these goals, Medicare now uses a value-based purchasing model consisting of (1) bundled payments to dialysis facilities for outpatient dialysis services, (2) a set of pay-for-performance initiatives known as the ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP),10 and (3) a tiered fee-for-service physician reimbursement schedule based on the number of visits per month.11

Table 1.

Major policy changes in ESRD and palliative care in the past 15 years

| Policy | Year of introduction | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Tiered fee-for-service physician reimbursement for dialysis services (“G-codes”) | 2004 | Changed physician reimbursement for outpatient dialysis services from capitated payment to tiered fee-for-service payments. |

| ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS; “the bundle”) | 2010 | A patient-level and facility-level adjusted per treatment (dialysis) payment for renal dialysis services that includes drugs, laboratory services, supplies and capital-related costs related to furnishing maintenance dialysis. |

| ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP) | 2010 | A value-based purchasing program in which payments to ESRD facilities are reduced for facilities that do not meet certain performance standards. |

| Pre-ESRD Education in the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA) | 2010 | Entitles Medicare beneficiaries with stage 4 CKD to receive six educational sessions about management of comorbid conditions, preventing complications, and kidney replacement therapy options. |

| Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) | 2015 | A Medicare value-based purchasing program that financially incentivizes healthcare providers to provide high-quality, cost-efficient care. |

| Comprehensive ESRD Care Model | 2015 | Dialysis clinics, nephrologists and other providers join together in ESCOs to coordinate care for beneficiaries with ESRD receiving dialysis. Providers are eligible for shared savings payments based on Medicare Part A and Part B costs and may be liable for shared losses. |

| Medicare Care Choices Model | 2015 | Allows Medicare beneficiaries to receive hospice-like support services while concurrently receiving curative care. Participation is limited to beneficiaries with advanced cancers, COPD, CHF, and AIDS. |

| Hospice Wage Index and Payment Rate Update | 2015 | Re-affirmed eligibility of dialysis patients with non-ESRD terminal diagnoses to receive both dialysis services and hospice |

| Advance Care Planning Reimbursement | 2016 | Voluntary advance care planning services may be billed by physicians and non-physician practitioners as a separate Medicare Part B service or an optional element of Annual Wellness Visit |

| CHRONIC Care Act (proposed) | 2017 | Expands telemedicine coverage under Medicare Advantage Plans, including telemedicine in home dialysis facilities and home-based primary care services for people with multiple chronic conditions. |

| Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act | pending | Establishes palliative care workforce training, supports national palliative care education and awareness campaign, and enhances research in palliative care. |

Abbreviations: CHIP – Children’s Health Insurance Program; ESRD, end-stage renal disease program; ESCO, ESRD Seamless Care Organization; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF, congestive heart failure

Current barriers to palliative care for seriously ill patients with CKD and ESRD

Uneven access to specialty palliative care services

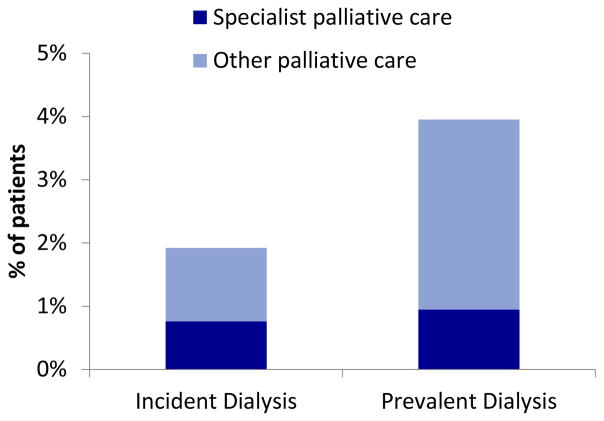

Most patients with ESRD who receive maintenance dialysis lack access to specialty palliative care services. In a survey of dialysis providers, access to specialty palliative care was identified as the second highest priority to improve palliative care for ESRD patients and was a key facilitator of decisions to forego or withdraw from dialysis.12,13 Medicare data indicate that 2% of incident dialysis patients and 4% of prevalent patients received palliative care services in 2013; of these, half received care from a palliative care specialist (Figure 1). These utilization rates are similar to those found in advanced heart failure, but far lower than rates observed in advanced cancer.14,15

Figure 1.

Prevalence of palliative care among incident and period prevalent Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD receiving maintenance dialysis in 2013. Specialist palliative care refers to care delivered by physician with specialty training in palliative care.

Lack of access to palliative care services is attributable to at least three factors. First, specialty palliative care services are regionalized in a limited number of geographic areas and within tertiary medical centers. In seven states, fewer than 40% of hospitals with more than 50 beds have a palliative care team.16 Consequently, the majority of U.S. patients who are seriously ill but are neither hospitalized nor imminently dying are unable to access specialist palliative care. Second, access challenges due to regionalization of palliative care are compounded by the time-intensive requirements for dialysis and associated travel. Third, there is a workforce shortage of specialty trained palliative care physicians (an estimated 10,000 more are needed to meet existing demand), while concurrently there is limited awareness of patients’ unmet care needs and limited training in palliative care among nephrology providers.12,17–19

Under-developed models of care for seriously ill patients with advanced CKD and ESRD

Palliative care is appropriate at any stage of an illness and can be delivered along with curative therapy. Perhaps the best-known model of palliative care in the U.S. is hospice care, a type of palliative care for patients with terminal illness who are forgoing curative or life-extending treatments. Hospice care covers all medical care related to the terminal illness, and can be delivered at home, in a nursing home, or in an inpatient facility. However, the hospice model alone is insufficient to meet the needs of seriously ill patients with advanced CKD and ESRD. Medicare hospice eligibility criteria require that patients have a life expectancy of six months or less if the disease takes its normal course and that patients forgo treatments related to their primary hospice diagnosis. This means Medicare beneficiaries can receive hospice care only if (1) they have advanced CKD, are expected to die within 6 months, and agree to forgo dialysis; (2) their terminal illness is ESRD and they withdraw from dialysis; (3) their terminal illness is ESRD and a hospice program agrees to pay the costs of dialysis care; or (4) they have a terminal illness unrelated to ESRD which allows them to receive concurrent hospice and dialysis care. Because the cost of dialysis is prohibitive for most hospice programs, access to hospice care is largely limited to ESRD patients who have an unrelated terminal diagnosis such as cancer or to the final few days of life after withdrawal from dialysis, a time frame generally considered insufficient to optimize end-of-life care.20 Because it is designed to care for patients with a terminal illness who experience a predictable progressive decline towards death, the hospice model is also not a good fit for patients with advanced CKD who elect to forgo dialysis, as their end-of-life illness trajectories may be unpredictable.21 Finally, lack of parity in reimbursement for outpatient palliative care programs compared to dialysis care disincentivizes outpatient palliative care; specifically, it is easier and more profitable to start a patient on dialysis than to manage the same patient with advanced CKD in an interdisciplinary palliative care program.13

The lack of a patient-centric model of care for seriously ill patients with advanced CKD and ESRD is exemplified by the absence of coordinated and meaningful advance care planning. Few patients engage in advance care planning, and the vast majority lack a written advance directive or surrogate decision maker, leaving them unprepared to make medical decisions in a crisis.22 For patients with multi-morbidity, maintenance dialysis is one of many complex treatment decisions they face, and limited data suggest dialysis may not meaningfully extend life for such patients.23,24 The current narrow focus on dialysis preparation misses an opportunity to explore patient goals as part of the advance care planning process. Separation between dialysis decision-making and advance care planning may result in care that is not aligned with patient preferences and leave patients feeling that they either lacked choice about dialysis or were uninformed about what to expect.25 Similarly, advance care planning is not routinely offered to patients receiving maintenance dialysis, contributing to high utilization of intensive procedures near the end of life.4,22

Misaligned incentives

The ESRD QIP is intended to incentivize high value care, but applying uniform standards of care to all patients irrespective of their treatment goals may be counter to patient-centered care.26,27 Patients with primarily palliative goals who wish to continue receiving dialysis are often held to the same quality standards in the ESRD QIP as patients who are candidates for kidney transplantation (Table 2). For example, incentives to increase use of arteriovenous fistulas could have the unintended effect of subjecting patients with limited life expectancy to procedures from which they are unlikely to benefit and may be harmed.28 Dialysis facility mortality rates do not distinguish between patients for whom death is an expected or even desired outcome, such as those who die after discontinuing dialysis, and those for whom death is unexpected. In response to criticism that the ESRD QIP is overly reliant on aspects of care that are easily measured rather than aspects of care that are meaningful to patients, two patient-reported outcomes, pain and depression, have been incorporated in the 2018 version of the QIP as reporting metrics. How best to utilize the information from these metrics to improve care remains the subject of considerable debate.26,27,29

Table 2.

Quality measures included in the 2018 ESRD QIP and the ESCO QIP, and their applicability for palliative care.

| ESRD Quality Measures | ESRD QIP | ESCO QIP | Applicable to palliative care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical measures | |||

| Standardized mortality ratio | √ | ||

| Blood stream infections | √ | √ | |

| Standardized hospitalization ratio | √ | √ | |

| Standardized readmission ratio | √ | √ | √ |

| Dialysis adequacy (Kt/V) | √ | √ | |

| Vascular access type | √ | √ | |

| Hypercalcemia | √ | √ | |

| Blood transfusions | √ | ||

| Patient experience with care | √ | √ | √ |

| Quality of life | √ | √ | |

| Reporting measures | |||

| Mineral metabolism | √ | ||

| Anemia management | √ | ||

| Pain assessment and follow-up | √ | √ | |

| Depression screening and follow up | √ | √ | √ |

| Healthcare personnel influenza vaccination | √ | ||

| Documentation of current medications | √ | √ | |

| Medication reconciliation post discharge | √ | √ | |

| Falls screening and plan of care | √ | √ | |

| Advance care plan | √ | √ | |

| Diabetes eye exam | √ | ||

| Diabetes foot exam | √ | ||

| Influenza vaccination (patient) | √ | ||

| Pneumonia vaccination (patient) | √ | ||

| Tobacco use screening and cessation plan | √ |

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease program; ESCO, ESRD Seamless Care Organization; QIP, Quality Incentive Program. Adapted from CMS’s comprehensive ESRD care model.

The goal of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) is to increase value in Medicare fee-for-service programs.30,31 Under this Act, providers must participate in either the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) or an advanced alternative payment model (advanced APM).32 Both arms are intended to incentivize the provision of cost-effective, high-quality care through appropriate metrics. However, of the 17 nephrologist-specific quality measures, only two relate to palliative care: advance care planning and hospice referral after dialysis withdrawal.33 Since providers only report on 6 metrics of their choosing (out of over 270 total metrics), many nephrologists will opt for quality measures that are easier to fulfill.

Under the advanced APM track, dialysis organizations are encouraged to join with nephrologists and other providers to form ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs). ESCOs are incentivized to create a person-centered, coordinated care experience.34,35 By financially aligning nephrologists, dialysis facilities, hospitals, nursing homes, and other providers involved in the care of patients with ESRD, the model intends to reduce incentives for volume and fragmentation of care. Because ESCOs are subject to many of the same quality metrics as the ESRD QIP and, in fact, have a more extensive pay-for-performance program than traditional dialysis facilities, concerns about misaligned incentives also apply to ESCOs (Table 2). Of note, a metric for presence of an advance care plan is applicable to ESCOs but is not in the ESRD QIP.36,37

Overall, the limited set of existing quality measures for palliative care means that the Quality Payment Program (QPP) that emerged from MACRA does not currently incentivize provision of palliative care for patients with advanced CKD and ESRD, though this may change once the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services develops and implements cost measures. A recent stakeholder panel identified gaps in quality measurement that are relevant to the care of seriously ill patients with ESRD (Table 3),38 and recommended the implementation or development of quality measures to address these gaps.

Table 3.

Recommendations to address gaps in quality measurement in serious illness care

| Recommendation | Issues relevant to ESRD |

|---|---|

| 1. Implement existing quality measures applicable to the seriously ill in Medicare quality programs | Advance Care Planning measure present in ESCO QIP |

| 2. Improve collection of patient and caregiver feedback | No existing quality measures in ESRD capture experience of patients who have died or cannot speak for themselves, or experience of bereaved family members |

| 3. Standardize data collection to help identify vulnerable individuals | Standardized functional and cognitive data is currently not captured by dialysis providers |

| 4. Create new tools to ensure patients are in control of their care | No measures exist to capture whether patients’ goals, preferences, and values are honored |

| 5. Develop and implement measures that align with new payment models | A separate set of incentives exists for the ESCO QIP (see Table 2) |

Abbreviations: ESRD – end-stage renal disease, ESCO – ESRD Seamless Care Organization, QIP - Quality Incentive Program

Recommendations are based on “Building Additional Serious Illness Measures into Medicare Programs“.38

Reforms to address barriers to palliative care for patients with CKD?

1. Expand access to palliative care

For communities with mature specialty palliative care programs, several strategies could increase access to this care. These include universal screening for palliative care needs, with palliative care referral as appropriate. Specific strategies for screening and suggested tools have been described.6,26 Partnerships with local palliative care and hospice programs are needed to facilitate timely palliative care and hospice referrals, protocols for co-management of patients, and best practices for dialysis withdrawal.

Provision of primary palliative care services by nephrology team members trained in palliative care, and/or delivery of specialty palliative care services at dialysis facilities are additional strategies that could expand access to palliative care. Delivery of specific elements of palliative care in dialysis facilities (such as symptom management and advance care planning) has been previously tested with mixed results, and one recent report has described feasibility of embedded palliative care in the dialysis facility.39–42 In addition, expanded training for fellows, practicing nephrologists, and interdisciplinary team members could alleviate the palliative care workforce shortage.43

2. Develop a new model of serious illness care for patients with advanced CKD

We propose that serious illness care for patients with advanced CKD should be redesigned around “early goals of care conversation” rather than using the current narrow disease-oriented focus on “early dialysis preparation”. In this proposed model, patients could receive multi-disciplinary team care for symptom management and decision support, commensurate to the level of care provided to home dialysis patients, across the care continuum from advanced CKD and ESRD. The model would be flexible enough to support populations with differing and/or evolving treatment goals, including patients who desire conservative care without dialysis, those preparing for dialysis, those who wish to delay dialysis for as long as possible, those who are not sure whether they want to receive dialysis, those who wish to receive palliative dialysis, and those receiving standard dialysis treatment.

There are several models and examples which may offer useful lessons for redesigning CKD care. These include organized programs of conservative non-dialysis management in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada;44,45 and U.S. community-based serious illness programs such as the Veterans Affairs Home Based Primary Care service and Program of All Inclusive Care for the Elderly.46 Common features of these models include team-based care, caregiver training, symptom management, and care transition management. The integration of palliative care into management of advanced heart failure also serves as a useful example, given the unpredictable disease trajectory shared by CKD and heart failure, and guidelines recommending palliative care consultation prior to implantation of left ventricular assist devices.47 Patients receiving care under such a model could have their own set of broad-based quality measures distinct from those of the ESRD QIP.

3. Test new payment models for delivering palliative care

Several new payment models show promise as potential means of delivering palliative care to seriously ill patients with ESRD, and should be high priorities for comparative effectiveness research.

The ESCOs may be the best developed payment model that is poised to improve delivery of palliative care to patients with ESRD under Medicare. An earlier iteration of the ESCO model found that rates of advance directive completion could be increased (though the effect on care near the end of life was not examined).48

The QPP is another opportunity to promote palliative care. Within the MIPS, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has yet to implement cost measures mandated by the legislation.33 These cost measures will use episodes of care, which encompass the treatment, aftercare, and complications associated with a specific condition, such as CKD.49 If constructed effectively, they will reward providers who are effective at coordinating care, reducing preventable complications, and curtailing unnecessary healthcare---goals that align with patients opting for less aggressive healthcare. Similarly, an advanced CKD care model analogous to the ESCOs could also promote palliative care. Such a model would likely qualify as an advanced APM and could incentivize patient-centered approaches to preparing for ESRD, including conservative care. The National Kidney Foundation and Renal Physicians Association have already started developing such a model and have introduced provisions to include palliative care.50 Efforts like these will require close input from the nephrology community to ensure that providers are neither dissuaded from nor incentivized to offer conservative care options when these do not align with patients’ goals and values.51

In 2017 Medicare launched the Care Choices Model, a new payment and delivery demonstration that allows beneficiaries to receive hospice-like support services from hospice providers while concurrently receiving curative or life-extending care.52 In this demonstration, Medicare will determine whether this new model increases access to supportive care services, improves quality of life and patient/family satisfaction, and changes use of life-extending treatments. While participation is currently limited to Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer, lung disease, heart disease, and AIDS, there may be an opportunity to extend this payment model to patients with ESRD with support from the nephrology community. The approach is conceptually similar to proposed models of “palliative dialysis” and “dialysis as destination treatment” that have been described for patients with ESRD who desire dialysis but whose goals are primarily palliative.53,54

Finally, recently passed and pending legislation addressing reimbursement for advance care planning, telemedicine for home-based primary care, and palliative care training (Table 3), serve as examples of additional policy measures that could support the provision of palliative care.

Potential pitfalls

Value-based models of care carry risks for undertreatment, cherry picking, poor quality of care, and cost-shifting to informal caregivers.16, 55 These risks might be mitigated by surveillance and transparent reporting of care processes, outcomes and patient experience of care. As for all care models, it will be important to guard against situations in which providers are incentivized to provide treatments that do not align with patient goals and values. Some have recommended disclosure of financial arrangements and better integration of shared decision-making to manage the potential ethical conflicts arising from cost containment incentives,55,56 such as the partnership between dialysis providers, hospitals and hospice organizations in ESCOs.

The diffusion of palliative care delivery innovations into practice could also be impeded by physician attitudes and perceptions about the benefits of palliative care. Effecting culture change to address these barriers is also crucial for disseminating and sustaining innovations. 57,58

Summary

New models of care and associated policies that makes the provision of interdisciplinary palliative care with or without dialysis financially possible are needed to counterbalance significant financial incentives to start all patients on dialysis, regardless of expected benefits and harms. Redesigning health care for patients with advanced CKD and ESRD will require coordinated efforts from key stakeholders, including patients, caregivers, professional societies, dialysis providers, ESRD networks, and Medicare and other payors, starting with local demonstrations of feasibility in receptive communities. Reforming healthcare delivery in ways that remove policy disincentives to palliative care, coupled with efforts to strengthen support for palliative care in the nephrology community, could transform the approach to caring for seriously ill patients with advanced CKD and ESRD.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work is supported by grants U01DK102150 and F32DK107123 from the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: MKT, AO, LH, EM and AHM have received grant support and/or consultant fees from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Himmelfarb J, Pereira BJ, Wesson DE, Smedberg PC, Henrich WL. Payment for quality in end-stage renal disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2004;15(12):3263–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000145893.61791.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(8):747–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eneanya ND, Hailpern SM, O’Hare AM, Kurella Tamura M, Katz R, Kreuter W, et al. Trends in Receipt of Intensive Procedures at the End of Life Among Patients Treated With Maintenance Dialysis. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2017;69(1):60–68. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of End-of-Life Care Provided to Patients With Different Serious Illnesses. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176(8):1095–102. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamura MK, Meier DE. Five policies to promote palliative care for patients with ESRD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2013;8(10):1783–90. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02180213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Hare AM, Armistead N, Schrag WL, Diamond L, Moss AH. Patient-centered care: an opportunity to accomplish the “Three Aims” of the National Quality Strategy in the Medicare ESRD program. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2014;9(12):2189–94. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01930214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison RS, Zieman S. Introduction to Series. Journal of palliative medicine. 2017;20(4):328. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Hare AM, Song MK, Kurella Tamura M, Moss AH. Research Priorities for Palliative Care for Older Adults with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of palliative medicine. 2017;20(5):453–60. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swaminathan S, Mor V, Mehrotra R, Trivedi A. Medicare’s payment strategy for end-stage renal disease now embraces bundled payment and pay-for-performance to cut costs. Health affairs. 2012;31(9):2051–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson KF, Tan KB, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Variation in nephrologist visits to patients on hemodialysis across dialysis facilities and geographic locations. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2013;8(6):987–94. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10171012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Culp S, Lupu D, Arenella C, Armistead N, Moss AH. Unmet Supportive Care Needs in U.S. Dialysis Centers and Lack of Knowledge of Available Resources to Address Them. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2016;51(4):756–61e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA. System-Level Barriers and Facilitators for Foregoing or Withdrawing Dialysis: A Qualitative Study of Nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(5):602–10. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiskar KJ, Celi LA, McDermid RC, Walley KR, Russell JA, Boyd JH, et al. Patterns of Palliative Care Referral in Patients Admitted With Heart Failure Requiring Mechanical Ventilation. The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1049909117727455. 1049909117727455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rush B, Hertz P, Bond A, McDermid RC, Celi LA. Use of Palliative Care in Patients With End-Stage COPD and Receiving Home Oxygen: National Trends and Barriers to Care in the United States. Chest. 2017;151(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meier DE, Back AL, Berman A, Block SD, Corrigan JM, Morrison RS. A National Strategy For Palliative Care. Health affairs. 2017;36(7):1265–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claxton RN, Blackhall L, Weisbord SD, Holley JL. Undertreatment of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2010;39(2):211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Unruh ML, Palevsky PM, et al. Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2007;2(5):960–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00990207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2010;5(2):195–204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, Leland NE, Miller SC, Morden NE, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(5):470–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Edmonds P, Donohoe P, Carey I, Jenkins K, et al. Symptoms in the month before death for stage 5 chronic kidney disease patients managed without dialysis. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2010;40(3):342–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurella Tamura M, Montez-Rath ME, Hall YN, Katz R, O’Hare AM. Advance Directives and End-of-Life Care among Nursing Home Residents Receiving Maintenance Dialysis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2017;12(3):435–42. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07510716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L. Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliative medicine. 2013;27(9):829–39. doi: 10.1177/0269216313484380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(7):1955–62. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song MK, Lin FC, Gilet CA, Arnold RM, Bridgman JC, Ward SE. Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2013;28(11):2815–23. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss AH, Davison SN. How the ESRD quality incentive program could potentially improve quality of life for patients on dialysis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2015;10(5):888–93. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07410714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen SS, Unruh M, Williams M. In Quality We Trust; but Quality of Life or Quality of Care? Seminars in dialysis. 2016;29(2):103–10. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver MJ, Quinn RR, Garg AX, Kim SJ, Wald R, Paterson JM. Likelihood of starting dialysis after incident fistula creation. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2012;7(3):466–71. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08920811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelstein FO, Finkelstein SH. Time to Rethink Our Approach to Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for ESRD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2017;12(11):1885–1888. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04850517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.114th Congress. Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015. 129 Stat. 87, (2015).

- 31.Lin E, MaCurdy T, Bhattacharya J. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act: Implications for Nephrology. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2017;28(9):2590–96. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017040407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare Program; End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System, Coverage and Payment for Renal Dialysis Services Furnished to Individuals with Acute Kidney Injury, Quality Incentive Program, Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics and Supplies Competitive Bidding Program Bid Surety Bonds, State Licensure and Appeals of Preclusion, Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics and Supplies Competitive Bidding Program and Fee Schedule Adjustments, Access to Care Issues for Durable Medical Equipment; and the Comprehensive End-Stage Renal Disease Care Model. CMS-1651-F (2016).

- 33.Department of Health and Human Services: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Model (APM) Incentive under the Physician Fee Schedule, and Criteria for Physician-Focused Payment Models. CMS-5517-FC, (2016).

- 34.Medicaid CfMa. Comprehensive ESRD Care Model: CMS.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wish D, Johnson D, Wish J. Rebasing the Medicare payment for dialysis: rationale, challenges, and opportunities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(12):2195–202. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03830414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CEC Initiative. [Accessed: 3rd May 2017];Appendix D. Quality Performance (non-LDO) 2017 Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/cec-qualityperformance-nonldo.pdf.

- 37.CEC Initiative. [Accessed: 30th March 2017];Appendix B: Financial Methodology (Non-LDO CEC Model) 2015 Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/cec-financial-nonldo.pdf.

- 38.Building Additional Serious Illness Measures into Medicare Programs. Discern Health. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weisbord SD, Mor MK, Green JA, Sevick MA, Shields AM, Zhao X, et al. Comparison of Symptom Management Strategies for Pain, Erectile Dysfunction, and Depression in Patients Receiving Chronic Hemodialysis: A Cluster Randomized Effectiveness Trial. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2013;8(1):90–99. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04450512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, Hanson LC, Lin FC, Hladik GA, et al. Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: a randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2015;66(5):813–22. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cukor D, Ver Halen N, Asher DR, Coplan JD, Weedon J, Wyka KE, et al. Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2014;25(1):196–206. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feely MA, Swetz KM, Zavaleta K, Thorsteinsdottir B, Albright RC, Williams AW. Reengineering Dialysis: The Role of Palliative Medicine. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(6):652–5. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, Kutner JS, Holley JL, Moss AH. Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: a cross-sectional national survey of fellows. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2015;65(2):233–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown M, Miller C. Running and setting up a Renal Supportive Care program. Nephrology (Carlton) 2013 doi: 10.1111/nep.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American journal of epidemiology. 2004;159(7):702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohn J, Corrigan JM, Lynn J, Meier D, Miller JL, Shega J, et al. Community-Based Models of Care Delivery for People with Serious Illness. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, Granger BB, Steinhauser KE, Fiuzat M, et al. Palliative Care in Heart Failure: The PAL-HF Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(3):331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arbor Research Collaborative for Health. End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Disease Management Demonstration Evaluation Report: Findings from 2006–2008, the First Three Years of a Five-Year Demonstration. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Department of Health and Human Services: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed: 30th March 2017];Episode-Based Cost Measure Development for the Quality Payment Program. 2016 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/Episode-Based-Cost-Measure-Development-for-the-Quality-Payment-Program.pdf.

- 50.National Kidney Foundation. Re: CMS-1651-P: Medicare Program; End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System, Coverage and Payment for Renal Dialysis Services Furnished to Individuals with Acute Kidney Injury, End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program, Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics and Supplies Competitive Bidding Program Bid Surety Bonds, State Licensure and Appeals Process for Breach of Contract Actions, Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics and Supplies Competitive Bidding Program and Fee Schedule Adjustments, Access to Care Issues for Durable Medical Equipment; and the Comprehensive End-Stage Renal Disease Care Model. [Accessed: 30th March 2017];2016 Available at: https://www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/20160818%20NKF%20response%20to%20questions%20on%20APMS%20in%202017%20ESRD%20PPS%20QIP.PDF. [PubMed]

- 51.Berns JS, Glickman JD, Reese PP. Dialysis Payment Model Reform: Managing Conflicts Between Profits and Patient Goals of Care Decision Making. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(1):133–136. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [accessed August 29, 2017];Medicare Care Choices Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Medicare-Care-Choices/

- 53.Grubbs V, Moss AH, Cohen LM, Fischer MJ, Germain MJ, Jassal SV, et al. A palliative approach to dialysis care: a patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2014;9(12):2203–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00650114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vandecasteele SJ, Kurella Tamura M. A patient-centered vision of care for ESRD: dialysis as a bridging treatment or as a final destination? Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2014;25(8):1647–51. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thorsteinsdottir B, Swetz KM, Albright RC. The Ethics of Chronic Dialysis for the Older Patient: Time to Reevaluate the Norms. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(11):2094–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09761014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pearson SD, Kleinman K, Rusinak D, Levinson W. A trial of disclosing physicians’ financial incentives to patients. Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166(6):623–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fung E, Slesnick N, Kurella Tamura M, Schiller B. A survey of views and practice patterns of dialysis medical directors toward end-of-life decision making for patients with end-stage renal disease. Palliative medicine. 2016;30(7):653–60. doi: 10.1177/0269216315625856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Pankratz VS, Song MK, Unruh M. Provider Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Surrounding Conservative Management for Patients with Advanced CKD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2016;11(5):812–20. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07180715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]