Abstract

Background and Purpose

The aim of the present study is to explore whether using 7 Tesla MRI, additional brain changes can be observed in Hereditary Cerebral Hemorrhage with Amyloidosis-Dutch type (HCHWA-D) patients as compared to the established MRI features of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy (sCAA).

Methods

The local institutional review board approved this prospective cohort study. In all cases, informed consent was obtained. This prospective parallel cohort study was conducted between 2012 and 2014. We performed T2*-weighted MRI performed at 7 Tesla (7T) in pre-symptomatic mutation carriers (n=11, mean age 35 ± 12yrs), symptomatic HCHWA-D patients (n=15, mean age 45 ± 14yrs), and in control subjects (n=29, mean age 45±14 yrs). Images were analyzed for the presence of changes that have not been reported before in sCAA and HCHWA-D. Innovative observations comprised intragyral hemorrhaging and cortical changes. The presence of these changes was systematically assessed in all participants of the study.

Results

Symptomatic HCHWA-D-patients had a higher incidence of intragyral hemorrhage (47% (7/15), controls 0% (0/29), p<0.001), and a higher incidence of specific cortical changes (40% (6/15) vs 0% (0/29), p<0.005). In pre-symptomatic HCHWA-D-mutation carriers, the prevalence of none of these markers was increased compared with control subjects.

Conclusions

The presence of cortical changes and intragyral hemorrhage are imaging features of HCHWA-D that may help recognizing sCAA in living patients.

Keywords: cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebrovascular disease/stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, magnetic resonance imaging, neuroradiology

Subject terms: Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Intracranial Hemorrhage, Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke, vascular disease

Introduction

Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy (sCAA) can only be diagnosed with certainty by means of post-mortem histological examination of the brain tissue. The Boston criteria, based on radiological findings, have been developed to help making the diagnosis sCAA during life.1 New MRI markers may further improve these criteria. Hereditary Cerebral Hemorrhage with Amyloidosis- Dutch type (HCHWA-D), a hereditary form of CAA, is considered to be a good model for studying sCAA.2

Current disease markers for sCAA include hemorrhagic changes on CT or MRI, including the presence of intra cranial hemorrhage (ICH), lobar microbleeds (MBs), subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), and superficial siderosis.3-6 In the pre-symptomatic phase of HCHWA-D, these markers are almost completely absent7, 8 which may be due to the fact that hemorrhagic lesions are a late manifestation of the disease, or due to the limited sensitivity of conventional MRI systems in detecting the presence of more subtle hemorrhagic manifestations. High resolution T2*-weighted MRI at ultra-high field strength (7T) takes full advantage of the increased spatial resolution, increased signal-to-noise and contrast-to-noise ratio associated with high-field MRI, and could provide a sensitive method to detect early or small haemorrhagic lesions. The aim of the present study is to explore whether using 7 Tesla MRI, additional brain changes can be observed in HCHWA-D patients as compared to the established MRI features of sCAA.

Materials and Methods

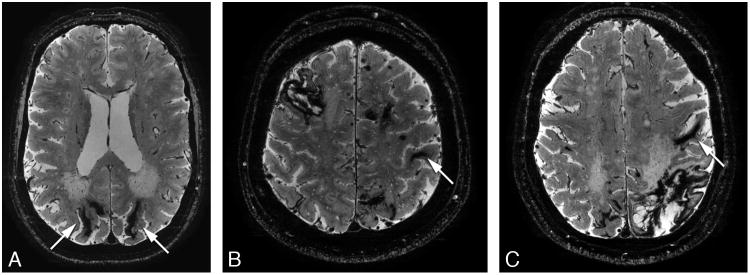

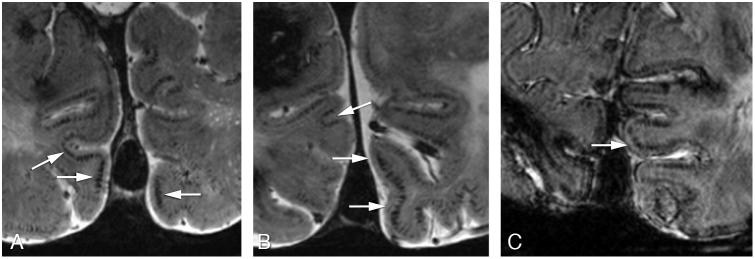

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article (and its online supplementary files). The ethics committee of our institution approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. In total 15 symptomatic (mean age 55 years), and 11 pre-symptomatic HCHWA-D patients (mean age 35 years) and 29 controls (mean age 45 years) participated. At 7T T2*-weighed gradient echo scans were performed. Conventional markers were scored: ICH, MBs, SAH and superficial siderosis as previously described.8 Based on prior visual inspection of the images by an experienced neuroradiologist, intragyral hemorrhaging and specific cortical changes were scored. Intragyral hemorrhaging is defined as a parenchymal hemorrhage restricted to the subcortical white matter of an individual gyrus (figure 1). A ‘striped’ cortical pattern is defined as linear hypointense stripes perpendicular to the cortex (figure 2). Please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org for supplementary information.

Figure 1.

High resolution 2D transverse T2*-weighted gradient echo 7 Tesla MRI scans showing intragyral hemorrhages (arrows) in three symptomatic patients.

Figure 2.

High resolution 2D transverse T2*-weighed gradient echo 7 Tesla MRI scans showing the striped cortex sign (arrows) in the occipital cortex of three symptomatic patients.

Statistics

Demographic characteristics were analyzed using post-hoc Mann-Whitney U-tests for MMSE score and age; for blood-pressure measurements a general linear model, univariate analysis adjusted for age and sex was performed; and for prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and the differences in sex a chi-square test was used. For each marker prevalence, post-hoc univariate general linear modelling was used, adjusted for age and sex. For all dichotome features the interobserver variability (kappa value) was calculated. Please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org.

Results

The characteristics of the study cohort are shown in supplementary table I. No differences were found in these characteristics among pre-symptomatic, symptomatic mutation-carriers and control subjects, except for a significant difference between symptomatic HCHWA-D patients and pre-symptomatic carriers/controls in mean MMSE score and a significant difference in age between symptomatic patients and pre-symptomatic carriers, which is inherent to the disease.

Prevalence of all hemorrhagic markers are shown in table 1. Results (% of variance explained and FDR corrected p-values) of univariate general linear modelling for each MRI marker for detection of hereditary CAA are shown in supplementary table II. Symptomatic HCHWA-D patients had a higher incidence of intragyral hemorrhage (47% (7/15), controls 0% (0/29), p<0.001), and a higher incidence of the striped cortex sign (40% (6/15) vs 0% (0/29), p<0.005). This striped cortex was only observed in the occipital lobe. In pre-symptomatic HCHWA-D mutation carriers, the prevalence of none of these markers was increased compared with control subjects.

Table 1.

Innovative MRI features and classic MRI markers for detection of hereditary CAA on T2*-w 7T MRI.

| Symptomatic carriers (n=15) | Pre-symptomatic carriers (n=11) | Controls (n=29) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovative Features | |||

| Intragyral hemorrhage % | 47 (7/15) | 0 (0/11) | 0 (0/29) |

| Striped cortex sign % | 40 (6/15) | 0 (0/11) | 0 (0/29) |

| Classic Markers | |||

| Lobar microbleeds % | 100 (15/15) | 18 (2/11) | 7 (2/29) |

| Superficial siderosis % | 93 (14/15) | 9 (1/11) | 0 (0/29) |

| ICH % | 100 (15/15) | 9 (1/11) | 0 (0/29) |

| SAH % | 47 (7/15) | 18 (2/11) | 0 (0/29) |

The results of the distribution of the classic markers have been published previously.8 Prevalence of all markers: ICH, MBs, SAH and superficial siderosis was increased in symptomatic HCHWA-D-patients (p<0.001), but not in pre-symptomatic mutation carriers.

The overlap; are patients positive for classic markers the same as the ones positive for the new markers, was also analysed. Patients with a striped cortex all showed microbleeds, 5/6 showed superficial siderosis, all showed ICHs, and 3/6 showed SAH. Of the patients with intragyral hemorrhage, all demonstrated microbleeds, all showed superficial siderosis, all showed ICHs, and 3/7 showed SAH. Of all symptomatic patients, three showed both intragyral hemorrhage and a striped cortex and all classic markers.

Interobserver agreement was calculated for the MRI markers. There was complete consensus concerning intragyral hemorrhaging (κ = 1.0). The κ value was substantial for a striped cortex, κ = 0.74 (p<0.001).

Discussion

Intragyral hemorrhage and a striped pattern in the occipital cortex at 7T MRI are imaging findings not detected earlier in HCHWA-D-patients, indicating innovative radiological manifestations of cerebral small vessel disease.

The striped cortex was found in 40% of the symptomatic mutation carriers and not in presymptomatic mutation carriers, which implicates that this marker is associated with more advanced stages of the disease. Interestingly, the striped cortex was only seen in the occipital lobe. The fact that in sCAA and HCHWA-D the occipital lobe is most severely affected with amyloidosis2, 9, 10 may indirectly implicate that this cortical pattern may be a specific CAA marker. Given the shape and course in the cortex, they could be caused by Aβ deposition in and along the penetrating arteries co-locating with iron causing abnormal cortical patterns on T2*-weighted MRI.11 Another explanation is the presence of calcification of the perforating cortical vessels which would also cause an hypointense signal on these images.12, 13 The used MRI technique may be especially sensitive to deoxy hemoglobine in veins and also might explain the pattern we observed. Histological analysis of these radiological observations is required to elucidate the underlying histological substrate.

Intragyral hemorrhages are a hemorrhagic manifestation of CAA which has not yet been described previously. These hemorrhages are large enough to been seen in earlier sCAA studies, however the increased spatial resolution, signal-to-noise and contrast-to-noise of 7T MRI makes evaluation of the exact location of an hemorrhage much more precise. However, future research could focus on finding this pattern of hemorrhages in sCAA patients and the implication it could have for the diagnostic value of the Boston criteria.

We note several limitations of this study. These markers were only detected in the symptomatic stage and are not the most common markers. Still, we believe there is an added value of these markers. These markers might be specific for sporadic CAA, and could have added value to the specificity of the Boston criteria. Moreover, it gives us information on the disease process and therefore increase our understanding of sporadic CAA. Furthermore, our results were obtained in HCHWA-D patients, who have a particularly severe form of CAA and are small population as a whole which limits our sample size.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: This work was supported by NIH (R01 NS070834). M.J.H.W. was supported by a personal grant from the Netherlands Heart Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: Prospects for clinical diagnosis and treatment. Neurology. 1998;51:690–694. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang-Nunes SX, Maat-Schieman ML, van Duinen SG, Roos RA, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM. The cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathies: Hereditary and sporadic. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg SM, Briggs ME, Hyman BT, Kokoris GJ, Takis C, Kanter DS, et al. Apolipoprotein e epsilon 4 is associated with the presence and earlier onset of hemorrhage in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 1996;27:1333–1337. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: Prospects for clinical diagnosis and treatment. Neurology. 1998;51:690–694. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linn J, Herms J, Dichgans M, Bruckmann H, Fesl G, Freilinger T, et al. Subarachnoid hemosiderosis and superficial cortical hemosiderosis in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:184–186. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman HH, Maia LF, Mackenzie IR, Forster BB, Martzke J, Woolfenden A. Superficial siderosis: A potential diagnostic marker of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in alzheimer disease. Stroke. 2008;39:2894–2897. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Opstal AM, van Rooden S, van Harten T, Ghariq E, Labadie G, Fotiadis P, et al. Cerebrovascular function in presymptomatic and symptomatic individuals with hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy: A case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:115–122. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30346-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Rooden S, van Opstal AM, Labadie G, Terwindt GM, Wermer MJ, Webb AG, et al. Early magnetic resonance imaging and cognitive markers of hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2016;47:3041–3044. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biffi A, Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: A systematic review. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea) 2011;7:1–9. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2011.7.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makela M, Paetau A, Polvikoski T, Myllykangas L, Tanskanen M. Capillary amyloid-beta protein deposition in a population-based study (vantaa 85+) Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2015;49:149–157. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Rooden S, Maat-Schieman ML, Nabuurs RJ, van der Weerd L, van Duijn S, van Duinen SG, et al. Cerebral amyloidosis: Postmortem detection with human 7.0-t mr imaging system. Radiology. 2009;253:788–796. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2533090490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinters HV, Natte R, Maat-Schieman ML, van Duinen SG, Hegeman-Kleinn I, Welling-Graafland C, et al. Secondary microvascular degeneration in amyloid angiopathy of patients with hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis, dutch type (hchwa-d) Acta neuropathologica. 1998;95:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s004010050793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sellal F, Wallon D, Martinez-Almoyna L, Marelli C, Dhar A, Oesterle H, et al. App mutations in cerebral amyloid angiopathy with or without cortical calcifications: Report of three families and a literature review. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2017;56:37–46. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.