Abstract

From a sample of African American families living in the rural South, this study tested the hypothesis that growing up in poverty is associated with heightened biological stress levels in youth that, in turn, forecast elevations in drug use in young adulthood. Supportive parenting during adolescence was hypothesized to protect youth’s biological stress levels from rising in the context of poverty. African American youth and their primary caregivers from 385 families participated in a 14-year prospective study that began when youth were 11 years of age. Data were collected from 2001 to 2016. All families lived in impoverished communities in the rural South. Linear regression models and conditional indirect effect analyses were executed in 2016 to test the study hypotheses. High number of years living in poverty across adolescence was associated with high catecholamine levels, but only among those youth who received low levels of supportive parenting. Youth catecholamine levels at age 19 forecast an increase in substance use from age 19 to age 25. Conditional indirect effects confirmed a developmental cascade linking family poverty, youth catecholamine levels, and increases in substance use for youth who did not receive high levels of supportive parenting. Current results suggest that, for some African American youth, substance use vulnerability may develop “under the skin” from stress-related biological weathering years before elevated drug use. Receipt of supportive parenting, however, can protect rural African American youth from biological weathering and its subsequent effects on increases in substance use during adulthood.

Keywords: Adolescent, African Americans, Alcohol Drinking, Catecholamines, Marijuana Smoking, Parenting, Poverty, Stress, Physiological, Tobacco Use

1. Introduction

A growing body of research has tested the hypothesis that growing up in poverty can contribute to lifelong trajectories in cognitive development, psychosocial development, and physical health (Bradley and Corwyn, 2002; Heckman, 2006; Miller et al., 2011a). More recently, researchers have begun to examine the ways in which growing up in poverty, and the life stressors that accompany it, presage initiation and escalation of drug use at later stages of development (Gordon, 2002; Sinha, 2008). This work is driven in part by surveillance data indicating that African Americans, who experience childhood poverty more than do any other ethnic group in the United States (Patten and Krogstad, 2015), use drugs less frequently than do Caucasians during adolescence yet engage in similar or even higher levels of substance use in adulthood (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2003). This pattern has been termed the racial crossover effect (Watt, 2008).

The explanation most frequently offered for the racial crossover effect involves the stressors young people experience as they transition to adult roles (Aseltine and Gore, 2005; Brody et al., 2010; Paschall et al., 2000). Emerging research, however, suggests that a sole focus on the effects of concurrent stressors is of limited value in understanding African Americans’ drug use etiology. Recent studies suggest that, for some young people, vulnerability to drug use in young adulthood is a developmental process occurring “beneath the skin” from the weathering of biological systems (Gordon, 2002; Sinha, 2008). Growing up in poverty can noticeably alter individuals’ sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and its release of stress hormones such as the catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine. Although beneficial for managing short-term threats, chronic hormonal surges triggered by the SNS can accumulate over time and dysregulate SNS activity, an effect that has been documented in both children (Evans, 2003) and adults (Miller et al., 2011a). Previous research has linked stress-regulated “weathering” from SNS activity to physical and mental health problems (Reuben et al., 2000), and some research has hypothesized that it also renders individuals more susceptible to drug use and abuse (Sinha, 2008). In this study, we tested components of this hypothesis. Specifically, we sought to determine whether African American youth in rural Southern environments who spent more years in poverty during adolescence would display elevated levels of the catecholamine stress hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine during young adulthood. In turn, we investigated the association between high catecholamine levels at the beginning of young adulthood and increases in drug use across the young adult years.

Not all children and adolescents who grow up in poverty, however, experience its adverse psychosocial and physiological consequences. Concerning psychosocial outcomes, multiple studies have indicated that supportive caregiving practices can offset many of the cognitive and behavioral disadvantages besetting children in poverty (Brody et al., 2012; Rutter, 2005). Mounting evidence also reveals that supportive parenting can protect youth physiologically by favorably molding the stress-response tendencies of vulnerable children (Cicchetti and Blender, 2006; Gunnar and Quevedo, 2007) and mitigating the wear-and-tear that adverse experiences inflict on children’s physiology (Chen et al., 2011; Evans et al., 2007). Parental support, for instance, has been shown to buffer the effects of neighborhood poverty on adolescents’ allostatic load, a measure of cardiometabolic risk (Brody et al., 2014), as well as the effects of low childhood SES on proinflammatory signaling (Chen et al., 2011) and metabolic profiles (Miller et al., 2011b) in adulthood. To date, however, much of this literature has relied on cross-sectional findings or retrospective reports of childhood environments (e.g., Chen et al., 2011 and Miller et al., 2011b; for an exception, see Evans et al., 2007). Consequently, prospective research exploring the protective effect of supportive parenting for youths’ SNS dysregulation is quite limited, particularly among minority, low-SES youth.

The current study was designed to address these limitations. Using a 14-year prospective research design involving rural African American youth and their primary caregivers, the current study tested the hypothesis that exposure to poverty for rural African American youth would be associated with high catecholamine levels that would then predict increases in drug use. Supportive parenting was expected to moderate the association between childhood poverty and catecholamine levels, with high levels of supportive parenting buffering African American youth from poverty-related biological weathering and its subsequent effects on increases in substance use during adulthood.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sample

The data for this study were drawn from the Strong African American Families Healthy Adult Project (SHAPE). The families resided in rural counties in Georgia in which poverty rates are among the highest in the nation and unemployment rates are above the national average (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor, 2014). African American primary caregivers and a target youth selected from each family participated in data collections; youths’ mean age was 11.7 years (SD = 0.3) at the first assessment in 2001; the last wave of data was collected from 2014 to 2016. Of the youth in the sample, 53% were female. At the first assessment, 80% of the caregivers had completed high school or earned a GED. Economically, these households can be characterized as working poor. The primary caregivers worked an average of 30.6 hours per week and had a median household income of $1612 per month. Of the families, 42.3% were living below federal poverty thresholds.

At the first assessment, 667 families were selected randomly from lists of fifth-grade students that schools provided (see Brody et al., 2004 for a full description of the recruitment process). From a sample of 561 at age 18 (a retention rate of 84%), 500 families were selected randomly to continue to participate in the study. The selection of a random subsample was necessary because of financial constraints associated with the costs of collecting and assaying catecholamine from urine samples. Of these 500 participants, 489 provided urine samples at age 19. Of this subsample, 385 agreed to take part in data collection at age 25; they constituted the sample for the present study (Supplemental Figure S1 presents a participant retention flow chart). Comparisons on demographic and study variables, using independent t-tests and chi-square tests, of the families in the study sample with those not in the sample revealed one difference: on average, families in the study sample experienced more years of poverty than did those not in the sample, t (663) = −2.59, p = .010; M study sample = 2.32 (SD = 1.91); M missing sample = 1.94 (SD = 1.77).

2.2. Procedure

All data were collected in participants’ homes using a standardized protocol. African American field researchers visited families’ homes to administer computer-based interviews at each wave of data collection, allowing responses to sensitive questions to be input privately by respondents. All assessments were conducted with no other family members present. Catecholamine and substance use were assessed when the youth were 19 years of age (M = 19.3, SD = 0.66). Data on substance use were also obtained when the youth were 25 years of age (M = 24.7, SD = 0.65). At each wave, primary caregivers consented to their minor youth’s participation in the study, and minor youth assented to their own participation. The Institutional Review Board of the sponsoring institution approved the study protocol.

2.3. Measures

Family poverty was computed when participants were 11 to 13 years of age, and again when they were 16 to 18 years of age. Caregivers provided data on their families’ income-to-needs ratios, based on family size. Poverty status at these six assessment waves were summed to determine the number of years youth spent living at or below federal poverty levels when they were 11 to 18 years of age (M = 2.32, SD = 1.91).

The supportive parenting construct, assessed at ages 11 to 13 and 16 to 18 and expressed as a composite, was derived from measures of parental support and nurturant-involved parenting. Parental support was measured using youth reports on two scales. The 4-item Emotional Support subscale from the Carver Support Scale (Carver et al., 1989) was administered at ages 11 to 13 and 16 to 18. On a scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true), youth responded to items such as, “I get emotional support from my caregiver” and “I get sympathy and understanding from my caregiver.” Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .78 to .90. The second support assessment, the 11-item Family Support Inventory (Wills et al., 1992), was administered at ages 16 to 18. Youth rated statements on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true) about the support their parents provided to them. Examples include, “I feel that I can trust my caregivers as someone to talk to,” and “If I talk to my caregiver they have suggestions about how to handle problems.” Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .94 to .95.

The nurturant-involved parenting instrument (Brody et al., 2001) was administered to youth at ages 11 to 13 and 16 to 17. This measure included 9 questions with responses ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). It was used to assess the extent to which parents were aware of the youth’s activities, talk with the youth about issues that bother the youth, listen to the youth’s perspectives during arguments, and consider the youth’s opinions when making decisions on family matters. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .76 to .89. The parent support, family support, and nurturant-involved parenting measures were highly correlated (rs = .58 – .77, ps < .001); measures were averaged, standardized, and summed to form an indicator of supportive parenting.

Substance use was assessed at participant age 19 and age 25. Participants reported their past-month frequencies of cigarette smoking, alcohol use, heavy drinking, and marijuana use on a widely used instrument from the Monitoring the Future Study (Johnston et al., 2007). A response set ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (more than two packs a day) was used for cigarette smoking; a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 5 (20 or more times) was used to measure alcohol use, heavy drinking, and marijuana use. Responses were summed to form a substance use composite, a procedure that is consistent with our own and others’ prior research (Brody and Ge, 2001; Newcomb and Bentler, 1988). Because the distributions of substance use were skewed, we applied a log transformation to normalize the data.

The protocol for measuring catecholamines when youth were 19 years of age was based on procedures that Evans (2003) and Brody et al. (2013b) developed for field studies involving children and adolescents. Details of data collection and assaying are documented elsewhere (see Brody et al., 2013b). In brief, all urine voided between 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. was collected and stored on ice in a container with metabisulfite as a preservative; four 10-ml samples were randomly extracted and deep frozen at −80° C until subsequent assays were completed. Epinephrine and norepinephrine were assayed with high-pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (Riggin and Kissinger, 1977). For epinephrine, mean intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for nonsequential duplicates are 27.1% (< 40 pg/ml), 13.5% (40 to 80 pg/ml), and 9.6% (> 80 pg/ml); pooled samples mean inter-assay CV for 60 to 140 pg/ml is 16.3%; and blanks read 7.0 ± 14.5 (SD) pg/ml. For norepinephrine, mean intra-assay CVs for nonsequential duplicates are 6.6% (< 400 pg/ml), 6.5% (400 to 800 pg/ml), and 7.1% (> 800 pg/ml); pooled mean inter-assay CV for 300 to 500 pg/ml is 10.3%; and blanks read 6.0 ± 10.3 (SD) pg/ml. Creatinine assay via Jaffe rate methods controlled for body size differences and incomplete urine voiding (Tietz, 1976). SNS catecholamine scores were calculated by summing the standardized scores of overnight epinephrine and norepinephrine (r = .54, p < .001).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Linear regression models were executed to test the study hypotheses. The first model was designed to determine whether supportive parenting at ages 11 to 18 buffered the detrimental effects of family poverty on catecholamine levels at age 19. This model estimated the main effects of family poverty, supportive parenting, and the hypothesized interaction of family poverty with supportive parenting in forecasting age 19 catecholamine levels. All interaction analyses were executed based on the conventions that Aiken and West (1991) prescribed, whereby the variables are first mean centered and interactions are calculated as the product of the centered variables.

Next, we executed a conditional indirect effect model to determine whether the protective effect of supportive parenting on the association between family poverty and catecholamine levels at age 19 also accounted for youth substance use at age 25. We hypothesized that family poverty at ages 11 to 18 would forecast age 19 catecholamine levels for youths who received low levels of parent support, and that age 19 catecholamine levels would forecast an increase in substance use from age 19 to age 25. The hypothesis was tested using regression-based conditional indirect effect analysis procedures (Hayes, 2013). First, the regression coefficients were calculated for the association between family poverty and catecholamine levels for youth who experienced low (simple slope a1) vs. high (simple slope a2) levels of parental support. Second, the regression coefficient for the association between age 19 catecholamine levels and age 25 substance use was calculated (simple slope b). Third, the conditional indirect effect in which catecholamine levels serve as a link connecting family poverty to substance use was quantified as the product of the two regression coefficients (a1 × b). In addition, nonparametric bootstrapping was used to obtain the bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (BCA) of parameter estimates for significance testing (Preacher et al., 2007). The parameter estimate was calculated 1000 times using random sampling with replacement to build a sampling distribution. All analyses were conducted in 2016 using IBM SPSS 24 (IBM Corporation, 2016) and the statistical macro package PROCESS (Hayes, 2012).

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for the study variables are presented in Supplemental Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. Buffering effects of supportive parenting on the association between family poverty and catecholamines

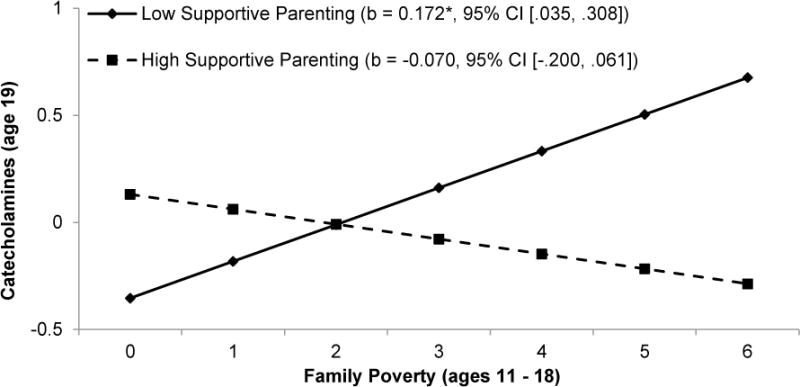

The first model, presented in Table 1, was designed to test the hypothesized buffering effects of supportive parenting. As predicted, a significant interaction of family poverty × supportive parenting emerged, b = −0.135, 95% CI [−0.244, −0.026], p = .015. To interpret this finding, we plotted estimated levels of catecholamines at low and high levels of family poverty and supportive parenting; the result is presented in Figure 1. High family poverty was associated with high levels of catecholamines when youth experienced low levels of supportive parenting [simple-slope = 0.172, 95% CI (0.035, 0.308), p = .014]. Conversely, for youth who received high levels of supportive parenting, family poverty was not associated with catecholamine levels [simple-slope = −0.070, 95% CI (−0.200, 0.061), p = .295]. Catecholamine levels were highest among youth who experienced high levels of family poverty and received low levels of parental support. Additional analyses were conducted to determine whether participant gender conditioned any of these findings; no interactions were detected.

Table 1.

Family poverty and supportive parenting at ages 11–18 as predictors of catecholamines at age 19

| Predictors | Catecholamines (age 19)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| b | 95% CI | |

| 1. Gender (male = 1, female = 0) | 0.205 | −0.159, 0.569 |

| 2. Substance use (age 19) | 0.330 | 0.079, 0.581 |

| 3. Family poverty (ages 11–18) | 0.051 | −0.041, 0.143 |

| 4. Supportive parenting (ages 11–18) | −0.042 | −0.243, 0.159 |

| 5. Family poverty × Supportive parenting | −0.135 | −0.244, −0.026 |

Data were collected from 2001 to 2016 from families in impoverished communities in the rural South. b = unstandardized regression coefficient; CI = confidence interval. Boldface indicates statistical significance; p < .05.

Fig. 1.

The effect of family poverty and supportive parenting at ages 11–18 on youths’ catecholamine levels at age 19. Data were collected from 2001 to 2016 from families in impoverished communities in the rural South. Numbers in parentheses refer to simple slopes for different levels of supportive parenting (low: 1 SD below the mean; high: 1 SD above the mean). *p < .05, two-tailed. CI = confidence interval.

3.2. Youth catecholamine levels at age 19 and increases in substance use from ages 19 to 25

Table 2 presents the regression model that tested the hypothesis that youth catecholamine levels at ages 19 would forecast an increase in substance use from age 19 to age 25. This hypothesis was supported [b = 0.025, 95% CI (0.008, 0.043), p = .005].

Table 2.

Catecholamines at age 19 as predictors of substance use at age 25.

| Predictors | Substance Use (age 25)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| ba | 95% CI | |

| 1. Gender (male = 1, female = 0) | 0.142*** | 0.079, 0.205 |

| 2. Substance use (age 19) | 0.218*** | 0.174, 0.261 |

| 3. Family poverty (ages 11–18) | −0.005 | −0.021, 0.011 |

| 4. Supportive parenting (ages 11–18) | 0.005 | −0.030, 0.040 |

| 5. Family poverty × Supportive parenting | −0.007 | −0.026, 0.012 |

| 6. Catecholamine levels (age 19) | 0.025** | 0.008, 0.043 |

Data were collected from 2001 to 2016 from families in impoverished communities in the rural South.

b= unstandardized regression coefficient. Boldface indicates statistical significance

p < .01,

p < .001.

CI = confidence interval

3.3. Indirect effect analyses linking family poverty, supportive parenting, catecholamines, and substance use

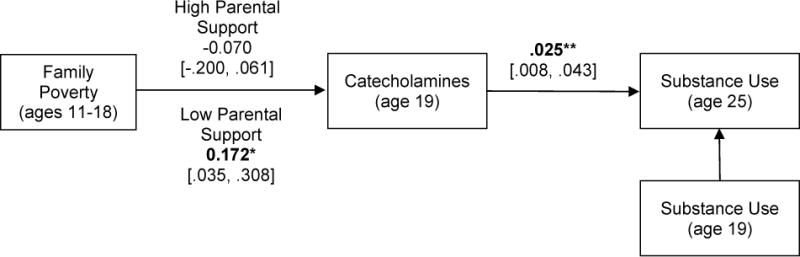

Figure 2 presents the results of the indirect effect model in which family poverty at ages 11 to 18 predicted youth catecholamine levels at age 19; these catecholamine levels, in turn, were predicted to forecast an increase in substance use from ages 19 to 25. The conditional indirect effects were calculated for low vs. high levels of supportive parenting. A significant indirect effect linking family poverty at ages 11 to 18 to youth substance use at age 25 (with age 19 substance use controlled) via youth catecholamines at age 19 only emerged when youth experienced low levels of parental support (indirect effect = 0.172 × 0.025 = 0.0043, 95% CI [0.0006, 0.0115]). No significant indirect effects emerged for youth who experienced high levels of parental support (indirect effect = −0.070 × 0.025 = −0.0018, 95% CI [−0.0065, 0.0007]).

Fig. 2.

The conditional indirect effect of family poverty at ages 11–18 on youths’ substance use at age 25 through catecholamine levels at age 19. Data were collected from 2001 to 2016 from families in impoverished communities in the rural South. Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p < .05, **p < .01). Numbers in brackets are 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which do not include zero. Gender was also controlled in the model.

4. Discussion

The results of this study make two major contributions to the literature. First, the results indicate that growing up in poverty is associated with biological markers of stress among some rural African American youth that, in turn, forecast elevations in drug use in young adulthood. Prior to this study, the effect of catecholamine levels on increases in drug use during young adulthood had been conjectured but rarely confirmed empirically. This result is consistent with surveillance data showing that growing up in poverty is a risk factor for later drug use and abuse (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2016) and, importantly, highlights a developmental, biological process that may contribute to heightened levels of substance use in young adulthood. Furthermore, whereas most prior efforts to explain the racial crossover effect have focused on contemporaneous stressors (Aseltine and Gore, 2005; Brody et al., 2010; Paschall et al., 2000), the current results suggest that, for some African American youth, substance use vulnerability is developing under the skin years before drug use begins. For clinical practice, this result and those associated with the “skin-deep” resilience phenomenon (Brody et al., 2013a; Miller et al., 2016) highlight the need for surveillance and screening in primary care settings for early detection of SNS dysregulation among rural African American youth and other children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

As the second main contribution of the current study, the aforementioned pathway emerged only among youth who grew up in the absence of supportive parenting. This result and similar findings from previous studies with other demographics (Chen et al., 2011; Evans et al., 2007) converge to suggest that the presence of a caring, supportive parent is key protective factor that prevents children who grow up in poverty from evincing impaired physical health profiles in adulthood. This finding is important because it indicates that the deleterious effect of poverty on children’s long-term health is not immutable. Pertinent to preventive medicine, the protective parenting practices identified in this study appear amendable to change from well-designed preventive interventions (Van Ryzin et al., 2016). Moreover, participation in efficacious programs designed to enhance supportive parenting has demonstrated stress-buffering effects for African American youth’s physical health, including assessments of catecholamine levels, cytokine levels, and epigenetic aging (Brody et al., 2016). To help expand the reach of these programs, pediatricians and prevention scientists have advocated primary care settings as implementation sites for family-centered preventive interventions (Leslie et al., 2016); to date, however, such practice remains uncommon.

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations of the study should be noted. First, consistent with other studies, self-reports of substance use are susceptible to inaccurate reporting. Second, no assessments of catecholamines were available before age 19 nor family poverty or parenting before age 11, precluding examination of these variables at earlier developmental stages. Third, the findings’ generalizability to ethnically and socioeconomically diverse samples from either rural or urban communities must be established empirically. Finally, participants retained in this sample experienced more poverty during childhood than did participants from the original sample who were not retained in this study. This difference may inflate the observed associations involving family poverty, suggesting that these observations may differ among samples with lower levels of family poverty. Future research can address these limitations.

5. Conclusions

Understanding the ways in which poverty and related stressors get “under the skin” to affect children’s long-term physical and behavioral health, as well as means of mitigating this effect, remains centrally important in order to promote the public health of some of the nation’s most vulnerable children. Results from the current study suggest that facilitating the receipt of supportive parenting can protect rural African American youth from SNS overactivation and its subsequent effects on increases in substance use in adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

▪

Childhood poverty forecast catecholamine levels for youth with unsupportive parents.

-

▪

Supportive parenting protected youth from heightened catecholamine levels.

-

▪

Elevated catecholamine levels at age 19 forecast increased substance use at age 25.

-

▪

For some African Americans, substance use vulnerability may develop under the skin.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number R01 HD030588 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and Award Number P30 DA027827 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, both to Gene H. Brody. The research presented in this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Institutes of Health, which had no role in the study’s design, execution, or submission for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors reports any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise. The authors thank Eileen Neubaum-Carlan for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this article.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aseltine RH, Jr, Gore SL. Work, postsecondary education, and psychosocial functioning following the transition from high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20:615–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Kogan SM, Smith K, Brown AC. Buffering effects of a family-based intervention for African American emerging adults. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:1426–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X. Linking parenting processes and self-regulation to psychological functioning and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:82–94. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger RD, Gibbons FX, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Simons RL. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72:1231–46. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, Grange CM. Translating longitudinal, developmental research with rural African American families into prevention programs for rural African American youth. In: King RB, Maholmes V, editors. The Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. Oxford University Press; USA, New York, NY: 2012. pp. 553–70. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Lei MK, Chen E, Miller GE. Neighborhood poverty and allostatic load in African American youth. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1362–e68. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair LD, Brown AC, Wills TA, Spoth RL, et al. The Strong African American Families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Beach SRH. Resilience to adversity and the early origins of disease. Development and Psychopathology. 2016;28:1347–65. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen E, Miller GE, Kogan SM, Beach SRH. Is resilience only skin deep? Rural African Americans’ preadolescent socioeconomic status-related risk and competence and age 19 psychological adjustment and allostatic load. Psychological Science. 2013a;24:1285–93. doi: 10.1177/0956797612471954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen Y-f, Kogan SM, Evans GW, Beach SRH, Windle M, Simons RL, Gerrard M, et al. Cumulative socioeconomic status risk, allostatic load, and adjustment: A prospective latent profile analysis with contextual and genetic protective factors. Developmental Psychology. 2013b;49:913–27. doi: 10.1037/a0028847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–83. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Miller GE, Kobor MS, Cole SW. Maternal warmth buffers the effects of low early-life socioeconomic status on pro-inflammatory signaling in adulthood. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011;16:729–37. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Blender JA. A multiple-levels-of-analysis perspective on resilience: Implications for the developing brain, neural plasticity, and preventive interventions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1094:248–58. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and poverty in the United States: 2013 (Current Population Reports P60-249) U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. A multimethodological analysis of cumulative risk and allostatic load among rural children. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:924–33. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Kim P, Ting AH, Tesher HB, Shannis D. Cumulative risk, maternal responsiveness, and allostatic load among young adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:341–51. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon HW. Early environmental stress and biological vulnerability to drug abuse. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:115–26. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper] 2012 Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science. 2006 Jun 30;312:1900–02. doi: 10.1126/science.1128898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24. IBM Corporation; Armonk, NY: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2006. I. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2007. (Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 07-6205)). [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LK, Mehus CJ, Hawkins JD, Boat T, McCabe MA, Barkin S, Perrin EC, Metzler CW, Prado G, et al. Primary health care: Potential home for family-focused preventive interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016;51:S106–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011a;137:959–97. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Brody GH, Chen E. Viral challenge reveals further evidence of skin-deep resilience in African Americans from disadvantaged backgrounds. Health Psychology. 2016;35:1225–34. doi: 10.1037/hea0000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Lachman ME, Chen E, Gruenewald TL, Karlamangla AS, Seeman TE. Pathways to resilience: Maternal nurturance as a buffer against the effects of childhood poverty on metabolic syndrome at midlife. Psychological Science. 2011b;22:1591–99. doi: 10.1177/0956797611419170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug abuse among racial/ethnic minorities, revised. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2003. (NIH Publication No. 03-3888). [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of substance abuse prevention for early childhood. 2016 Mar 9; Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-substance-abuse-prevention-early-childhood.

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Consequences of adolescent drug use: Impact on the lives of young adults. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Flewelling RL, Faulkner DL. Alcohol misuse in young adulthood: Effects of race, educational attainment, and social context. Substance Use and Misuse. 2000;35:1485–506. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten E, Krogstad JM. Black child poverty rate holds steady, even as other groups see declines. Fact Tank, Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2015. Jul 14, [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben DB, Talvi SLA, Rowe JW, Seeman TE. High urinary catecholamine excretion predicts mortality and functional decline in high-functioning, community-dwelling older persons: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Journals of Gerontology: Series A. Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2000;55:M618–M24. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.10.m618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggin RM, Kissinger PT. Determination of catecholamines in urine by reverse-phase liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Analytical Chemistry. 1977;49:2109–11. doi: 10.1021/ac50021a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter ML. Environmentally mediated risks for psychopathology: Research strategies and findings. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145374.45992.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1141:105–30. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietz NW. Fundamentals of clinical chemistry. 2nd. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Kumpfer KL, Fosco GM, Greenberg MT. Family-based prevention programs for children and adolescents: Theory, research, and large-scale dissemination. 1st. Psychology Press; New York, NY: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Watt TT. The race/ethnic age crossover effect in drug use and heavy drinking. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2008;7:93–114. doi: 10.1080/15332640802083303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Vaccaro D, McNamara G. The role of life events, family support, and competence in adolescent substance use: A test of vulnerability and protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20:349–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00937914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.