Abstract

Both lifespan psychology and life course sociology highlight that contextual factors influence individual functioning and development. In the current study, we operationalize context as county-level care services in inpatient and outpatient facilities (e.g., number of care facilities, privacy in facilities) and investigate how the care context shapes well-being in the last years of life. To do so, we combine 29 waves of individual-level longitudinal data on life satisfaction from now deceased participants in the nationwide German Socio-Economic Panel Study (N = 4557; age at death: M = 73.35, SD = 14.20; 47% women) with county-level data from the Federal Statistical Office. Results from three-level growth models revealed that having more inpatient care facilities, more employees per resident, and more staff in administration are each uniquely associated with higher late-life well-being, independent of key individual (age at death, gender, education, disability) and county (affluence, demographic composition) characteristics. Number of employees in physical care, residential comfort, and flexibility and care indicators in outpatient institutions were not found to be associated with levels or change in well-being. We take our results to provide empirical evidence that some contextual factors shape well-being in the last years of life and discuss possible routes how local care services might alleviate terminal decline.

Keywords: County, Socio-Economic Panel, Life satisfaction, Care, Regional differences

Introduction

Lifespan psychological and life course sociological theories emphasize the importance of contextual factors for individual functioning and development across adulthood (Bronfenbrenner 1979). For example, neighborhoods, municipalities, and nations have all been found to shape individual-level behavioral and emotional outcomes (Aneshensel et al. 2007; Sampson et al. 2002). This line of inquiry has established that aspects of both the proximal neighborhood and macro-cultural context play a role in the development of health and well-being in adults aged 60 years and older (Litwin 2010; Pruchno et al. 2012), with care provision emerging as one of the most important factors influencing older adults’ quality of life (Kane et al. 2004). However, less is known about how regional differences in the provision of care services (e.g., the number of facilities in a county) shape individual differences at the very end of life—in terminal decline—specifically, the often observed steep and accelerated decrements in well-being that manifest in the very last years of life (e.g., Vogel et al. 2013). Following Lawton (1982), Wahl et al. (2012), and others, we hypothesize that local care provision is especially influential at the very end of life when people are faced with frequent and severe impairments in the health and cognitive domains. We operationalize geographic context as local healthcare service characteristics. Long-term longitudinal individual-level data from the Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP), combined with county-level data from German Federal Statistical Office, provide an analysis sample of 4557 deceased participants who contributed, on average, 7 reports over the last 15 years of their lives. With representation across 95% of German counties, we examine whether the quality (resident-to-staff ratio, expertise of staff), quantity (number of care facilities), residential comfort (number of private beds), and flexibility (in bed provision) of care are related to higher levels and less pronounced declines in late-life well-being (after accounting for relevant individual and county demographics).

Linking context with individual functioning and development

The finding that several individual functions and outcomes including well-being decline with proximity to death has been labeled terminal decline (Backman and MacDonald 2006). Terminal decline has been either characterized with an accelerated declining trajectory (linear and quadratic change components) or two phases with a turning point to steeper decline in the last 3–6 years (linear splines invoking two phases of decline). In the midst of such steep average decline, substantial individual differences exist in levels of well-being, rate of terminal decline, and the timing of the onset of decline (for an overview, see Gerstorf and Ram 2013). Identifying individual- and regional-level predictors of these differences promises to inform research and policy about ways to optimize the allocation of resources during a phase of life that typically portends enormous individual and societal burdens and costs (Payne et al. 2007).

Tenets of lifespan psychology (Baltes 1997) and the environmental docility hypothesis (Lawton et al. 1990) suggest that context characteristics become increasingly relevant as people age because the frequent and often severe health and cognitive declines make the person–context system fragile. These theories suggest that functional ability and life satisfaction become increasingly tied to the available and accessible daily amenities (e.g., neighborhood pharmacies, parks). In addition, contextual factors may operate as moderators by regulating up and down how individual risk and protective factors shape individual functioning and development (Gerstorf and Ram 2012; Glass and McAtee 2006). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; World Health Organization 2002) suggests that one particularly important context which can promote well-being is local healthcare, including long-term and short-term care, home-based and community-based care, specialty hospitals, and residential and non-residential care facilities. For example, availability of community care services might reduce the burden of caregivers in the family and allow them more off time and—as a local resource—lead to enhanced well-being.

Consistent with these notions, empirical studies have repeatedly found that a variety of contextual factors shape individuals’ physical and mental health (King et al. 2011; McFarland et al. 2012; Pruchno et al. 2012; Windsor et al. 2012). For example, regional characteristics such as barrier-free living and higher neighborhood SES were each related to higher well-being (in Sweden and Germany: Wahl et al. 2009; in the USA: Wight et al. 2011). In one of a few studies examining the relation between regional context (gross domestic product, number of doctors per person, unemployment rate) and late-life well-being, Gerstorf et al. (2010) found in a German nationwide sample that between-county differences accounted for some 8% of the between-person differences in both level of well-being and rate of terminal decline, with those individuals living and dying in lower gross domestic product (GDP) counties generally having lower well-being. Also, cross-level interaction effects indicated that county-level characteristics moderated associations between individual characteristics and rates of well-being decline. For example, in counties with high unemployment rates, disparities between education groups in both level and change in late-life well-being were exacerbated. Moving on from rather broad contextual measures such as GDP, examining more fine-grained aspects of regional context may reveal additional insights.

County-level healthcare services and late-life well-being

Provision of care is particularly relevant in late-life (e.g., 64% of Germans aged 90+ being in need of care; Federal Statistical Office 2014). Infrastructure for care provision is regulated at the county level along with responsibility (or in the US eligibility for Medicaid) for supporting individuals whose care needs exceed the care insurance amount and who cannot cover these additional expenses from own sources (in the USA; Choi 2014). Of course, counties and regions differ in the quantity and quality of care they can support (e.g., in the USA; Walshe and Harrington 2002). Thus, county-level provisions may produce and/or “regulate” individuals’ risk for terminal decline in well-being through direct or indirect (e.g., through social network, friends, and family receiving care) contact with the services. To illustrate, the extent to which functional limitations impair individuals’ well-being may depend on characteristics of the county people are living in. If outpatient care services are available and of sufficient quality, persons may be able to continue living as usual. Remaining in regular contact with family and continuing with daily routines may help people to remain satisfied with their lives despite disability (Wahl et al. 2009). In contrast, if outpatient care is not available, the person may need to move, thus losing access to social resources.

There is empirical evidence that healthcare service characteristics relate to quality of life and well-being. For example, Kotakorpi and Laamanen (2010) reported that life satisfaction was higher in municipalities with more healthcare expenditure in Finland. Relevant healthcare service characteristics include lack of private space, lack of outdoor activity, and care staff not having enough time to assist recipients when necessary (Guse and Masesar 1999). We extend earlier work (Gerstorf et al. 2010) by examining a range of before-uninvestigated service characteristics at the county level (e.g., care).

To derive hypotheses about how regional care indicators influence well-being, we use the Andersen healthcare utilization model (Andersen 1995) and the conceptual framework for the evaluation of palliative care integration (Bainbridge et al. 2016). Andersen’s healthcare utilization model suggests that local care services are an enabling resource to healthcare utilization which in turn leads to evaluations of health and well-being. Characteristics such as better care ratio between employees and care recipients, higher number of facilities, and higher number of beds are all expected to lead to higher well-being. Similarly, the evaluation framework of palliative care integration suggests that more favorable employee characteristics in care facilities (e.g., expertise) and good care provision characteristics (e.g., long term, flexible) are associated with higher satisfaction with care which in turn might lead to higher general satisfaction.

We examine how county-to-county variation in objective features of counties’ inpatient and outpatient healthcare facilities relates to residents’ late-life well-being. Inpatient institutions are those in which people receive professional care and stay overnight, during the day, for a couple of weeks, or even permanently. Outpatient institutions provide care services to the patients’ home. The distinction is important because the living situation often vastly differs. For example, recipients of outpatient services can stay at home and realize “aging in place” by living in familiar environment. Thus, a regional context with provision of outpatient facilities should be associated with higher levels and slower terminal decline in life satisfaction. Five dimensions of regional care may be particularly relevant for late-life well-being.

Quality of care (attention)

Worse resident-to-staff ratio (care ratio) has been found to relate to lower quality of life (Kane et al. 2004), probably because employees who have to care for more patients are not able to fulfill each patient’s needs. In a similar vein, fewer staff hours and challenging work obligations have also been associated with lower quality of the care provided and lower quality of life of the care recipients (Harrington et al. 2000).

Quantity of care

The county-level number of outpatient facilities and number of inpatient facilities are important because living in a region with many care facilities might be associated with higher quality of care due to competition between facilities. In addition, individuals in need of care do have more choice to find a specialty facility that fits their needs. For example, they could reside more closely to their home or choose a facility that provides specialized expertise for their specific needs (e.g., dementia).

Quality of care (expertise)

Expertise of the staff and the hours the staff spends on tasks (main task of employee) have been found to play a role for quality of life (Shippee et al. 2015). For example, more hours spent on a given professional activity is associated with higher quality of life. In addition, not only employees who provide care are important in care facilities. Fewer administrative staff and fewer housekeeping staff have both been associated with lower quality of life of residents (Degenholtz et al. 2006), probably because the staff primarily responsible for care also need to take over administrative and housekeeping duties.

Residential comfort

Privacy has been repeatedly linked with reports of quality of life and well-being (Robichaud et al. 2006), even if such private space is restricted to receive visits (Guse and Masesar 1999).

Flexibility of care

We consider the flexibility in bed provision as an indicator of the number of beds in a given facility, averaged across the county, which can be used for short-time occupancy, night occupancy, day occupancy, etc. This kind of care provision can be expected to be a highly relevant county-level resource because it supports close others who take care of individuals full-time or part-time (e.g., by enabling them to go on vacation).

The present study

We examine how county-level healthcare service characteristics are related to late-life change in individuals’ well-being by applying three-level growth curve models to an integrated data set comprising (a) up to 29-year annual longitudinal data from now deceased participants in the German SOEP (N = 4557) and (b) county-level healthcare data (N = 371 counties) obtained from the German Federal Statistical Office. We assume that healthcare service characteristics constitute important resources late in life when people often need to adjust their lives to an ever-increasing risk for frequent and severe health challenges. Drawing from and expanding research on earlier phases of life that had used self-reports of service characteristics, we consider registry-based data on five sets of county-level healthcare service characteristics. In particular, we expect that living and dying in counties with fewer residents per employee, more inpatient and outpatient facilities, more staff in administrative positions, more private beds, and more flexible beds to report higher levels of late-life well-being and less pronounced terminal decline. We also explore whether and how these healthcare characteristics operate as moderators for how individual risk and protective factors relate to late-life well-being and change (i.e., with interactions between care indicators and individual characteristics). Our models covary for relevant individual (age at death, gender, education, disability) and county (affluence, demographic composition; Choi 2014) characteristics.

Method

Participants

Individual-level data were drawn from the SOEP, a longitudinal, nationally representative adult lifespan study with yearly assessments since 1984 (Headey et al. 2010). We selected participants who (a) were known to have died between 1984 and 2013 and (b) had provided at least one report of life satisfaction during the last 10 years of their life. The SOEP has long served as a resource for mortality-related analyses in Germany (Brockmann and Klein 2004). In total, the analysis sample consists of 31,448 annual reports of life satisfaction from N = 4557 (47% women, 90% born in Germany) by now deceased participants (median year of death = 2001), 77% of whom provided data on at least three occasions (M = 6.90, SD = 4.48, range = 1–17) before they died (between 18 and 101 years of age, M = 73.35, SD = 14.20). On average, these participants first evaluated their life satisfaction 9 years before death and they last evaluated their life satisfaction 2 years before death.

Counties

County-level data were drawn from two sources. Economic, service, and demographic county characteristics were derived from INKAR (Indikatoren und Karten zur Raum- und Stadtentwicklung in Deutschland und in Europa, the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development; BBSR) data. Care provision variables were derived from Care Statistics in Germany data maintained by the Federal Statistical Office (2014). Since 1999, all approved inpatient and outpatient care institutions (in addition to organizations of health insurances) are obliged to provide information on facilities, employees, funding, and care recipients in a biannual cycle. Using the average year of death for linking, the current analyses derived care provision variables from 2001 data on facilities and employees from 10,626 inpatient facilities (per county: M = 28.64, SD = 39.87) and 12,584 outpatient facilities (per county: M = 33.92, SD = 48.67). Anonymity rules require that county-level summaries aggregate a minimum of three care recipients, employees, and facilities. Keeping these standards, individual and county data were merged using community identification numbers. Because individual-level residence data were based on 2011 maps, and county boundaries change, some transformations were required. First, sparse institutional data required merging of 12 counties into six geographic units (pseudo-counties). Second, 2001 county (and pseudo-county) identifiers were transformed to 2011 mapping. This was possible except for 7 counties that had, by 2011, been split into 18 counties. These counties were kept in their 2001 form. Third, counties that still did not meet anonymity requirements after these steps (n = 14) were merged with the adjacent county with the longest shared border and/or a historical tie. These procedures resulted in a total of 383 pseudo-county units to represent the actual 402 counties that existed in 2011. SOEP individual-level data were then merged. Across-county migration for people in the last 5 years of their lives was low (9.11%). Coverage was good, with the 4557 decedents nested within over 95% of the counties (n = 371 out of n total = 383), with an average of 12.50 persons in each county (SD = 12.83; range = 1–155).

Measures

Individual level

Well-being

In the SOEP, life satisfaction was measured annually as response to the item “How satisfied are you with your life, all things considered?” on a scale from 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied; see Fujita and Diener 2005; Schimmack and Oishi 2005). For convenience of comparison to earlier reports, scores were transformed to T-metric (M = 50, SD = 10) based on the larger SOEP sample of deceased and non-deceased participants in 2002 (M = 6.90, SD = 1.81).

Covariates

We included four individual-level variables as time-invariant covariates: age at death, gender, years of formal education (M = 10.91, SD = 2.20), and disability. At each wave, participants were asked whether they had been “officially certified as having a reduced capacity to work or being severely handicapped” (Lucas 2007). The time-invariant variable used here is a binary contrast distinguishing participants who were officially designated as disabled at any time during the study (n = 2193) and those who never received an official disability designation (n = 2364).

County level

Quality of care (attention)

Care ratio is calculated as the number of employees divided by the number of recipients per institution and then averaged across institutions in a county. Two variables indicate guidance ratio or possible working overload per county, separately for inpatient and outpatient institutions.

Quantity of care

Two variables, number of outpatient care facilities and number of inpatient care facilities (cf. number of hospitals; Kottwitz 2014), depict the number of officially acknowledged care facilities from public and private agencies per county. Outpatient institutions can be affiliated to inpatient institutions or run stand-alone. Following usual practice, the total number of institutions per county was adjusted (i.e., divided) by potential care recipients (number of inhabitants aged 75 and older) to represent the number of care facilities relative to potential care recipients.

Quality of care (expertise)

Main task of employee For each employee in inpatient and outpatient facilities, a main work domain was assigned in the following domains: physical care and administration (e.g., management, utility area, household assistance). Main task of employee denotes the sum of employees relative to the number of institutions in a county, separately for inpatient and outpatient facilities.

Residential comfort

Privacy was quantified in two ways: number of private beds, calculated as the total number of available rooms with single beds relative to the number of potential care recipients (inhabitants aged 75 and higher), and number of non-private beds, calculated as the total number of rooms with two and more beds divided by the number of potential care recipients.

Flexibility of care

Flexibility in bed provision was quantified as the average number of beds available for short-time occupancy, night occupancy, day occupancy, and other use. Capacity was measured as the average number of beds available for permanent care. These variables were kept in absolute units rather than scaled to population.

Covariates

Two county-level variables were used as time-invariant covariates. Affluence of the county was calculated as a sum of relative ranks of county GDP (euro per inhabitant) and general healthcare access (number of doctors per 100,000 inhabitants) after standardizing each variable. Proportion of individuals aged 75 and higher in percent reflects the demographic composition of each county.

Data analysis

The hierarchical nature of the data (repeated occasions nested within persons nested within counties) was accommodated and modeled using standard growth models (Ram and Grimm 2015) within a multilevel modeling framework. At the within-person level (Level 1), models were specified as

| 1 |

where well-beingtic at occasion t for individual i in county c is modeled as a function of a person-specific intercept, β 0ic (located 2 years before death), individual-specific linear, β 1ic, and quadratic β 2ic rates of change in relation to time-to-death (TTD), and residual error, e tic. At the between-person level (Level 2), the person-specific coefficients were modeled as a function of individual factors (age at death, education, gender, and disability)

| 2 |

where , , and indicate the prototypical trajectory in county c, and u 0ic and u 0ic are residual, unexplained between-person differences that are assumed to be multivariate normally distributed, correlated with each other and uncorrelated with the residual errors, e tic. At the between-county level (Level 3), the county-level coefficients were modeled as

| 3 |

where , , and characterize the life satisfaction trajectory of the average person in the average county, and the vs are unexplained between-county differences that are assumed multivariate normally distributed, correlated with each other, and uncorrelated with the other residuals. To keep the model parsimonious, nonsignificant higher-order interactions were trimmed iteratively toward a 2-way interaction limit, always retaining the relevant lower-order interactions when any higher-order interactions remained. Models with a full random effects structure (for intercepts, linear and quadratic rates of change) were estimated, but provided only very minor improvement in model fit (AIC: 229,970 vs. 230,613) and the same pattern of findings. As well, robustness checks across different data treatments (e.g., removing counties with less than 7 persons) and different sets of covariates (e.g., pre-government household income) all provided the same pattern of results. For parsimony, we thus report results from the simpler model described above (i.e., no random effects for the quadratic change component). All models were estimated using SAS Proc Mixed (SAS Institute Inc. 2009) with incomplete data treated as missing at random in the context of the attrition-informative covariates (Little and Rubin 1987). TTD was centered at 2 years prior to death, with all other predictors centered at sample means.

Results

The proportion of between-person differences in terminal decline that might be attributed to county-level differences was quantified for the intercept (expected life satisfaction 2 years prior to death) as /() = 5.52/(94.78 + 5.52) = .06, and for the linear slope as /() = 0.04/(0.71 + 0.04) = .06. These proportions are similar to earlier reports (Gerstorf et al. 2010). Descriptives and correlations among the county-level care provision variables that might explain these differences are shown in Table 1. Generally, the correlations are in the low to moderate range, reducing concerns about multicollinearity and indicating that the measures from the same general domain (e.g., privacy) reflected different aspects of care provision (e.g., r = .36 between number of private beds and number of non-private beds), thereby justifying the inclusion of multiple indicators per set of healthcare characteristic. Where the correlations are high (e.g., r = .87 between bed capacity and number of physical care worker), the associations reflect structural constraints (e.g., having more beds requires having more workers).

Table 1.

Descriptive and correlations among county-level care indicators

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Affluence | 90.10 | 31.26 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Proportion people aged 75+ | 7.56 | 1.10 | .40 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3 | Care ratio inpatient | 2.58 | 0.43 | −.02 | .03 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4 | Care ratio outpatient | 1.36 | 0.23 | −.31 | −.15 | .14 | 1 | |||||||||

| 5 | Number inpatient institutions | 0.002 | 0.08 | −.20 | .05 | .01 | −.03 | 1 | ||||||||

| 6 | Number outpatient institutions | 0.002 | 0.06 | −.10 | −.19 | −.44 | −.17 | .31 | 1 | |||||||

| 7 | Main task physical care inp. | 13.16 | 3.94 | .41 | .06 | .19 | .11 | −.66 | −.32 | 1 | ||||||

| 8 | Main task physical care outp. | 35.96 | 10.54 | .27 | .14 | .34 | .39 | −.16 | −.59 | .31 | 1 | |||||

| 9 | Main task administration inp. | 5.26 | 3.16 | .28 | .12 | .47 | .12 | −.47 | −.36 | .78 | .32 | 1 | ||||

| 10 | Main task administration outp. | 16.08 | 5.45 | .26 | .06 | .10 | .51 | −.22 | −.41 | .31 | .60 | .20 | 1 | |||

| 11 | Number private beds | 0.05 | 0.02 | .15 | .08 | −.02 | −.04 | .58 | .27 | −.14 | .01 | −.05 | −.12 | 1 | ||

| 12 | Number non-private beds | 0.06 | 0.02 | −.04 | .14 | −.17 | −.03 | .62 | .31 | −.17 | −.18 | −.14 | −.10 | .36 | 1 | |

| 13 | Flexibility in bed provision | 4.58 | 2.64 | .06 | −.08 | −.09 | .14 | −.33 | .02 | .23 | .07 | .13 | .09 | −.17 | −.27 | 1 |

| 14 | Capacity beds | 73.48 | 19.03 | .41 | .11 | −.15 | .05 | −.62 | −.14 | .87 | .16 | .65 | .22 | −.01 | −.00 | .16 |

N = 371 counties. M mean, SD standard deviation, Inp. inpatient, Outp. outpatient

Correlations in bold significant at p < 0.01

County-level healthcare services and late-life well-being

Results from the final three-level growth curve model with both individual-level and county-level care provision variables as predictors are shown in Table 2. Model parameters indicate a typical trajectory of terminal decline with an intercept of π 000 = 44.51, located 2 years before death, a linear decline of π 100 = −1.44 points per year (1.5 standard deviations across a 10-year period), and some concave curvature of π 200 = −0.06. Variance parameters indicate the existence of statistically significant and sizable differences between individuals and counties in both levels and rates of terminal decline. Higher age at death (γ 01 = 0.03) and more years of education (γ 03 = 0.47) were associated with higher level of life satisfaction, and disability was associated with lower level of life satisfaction 2 years before death (γ 04 = −5.52 for individuals with disability). Individuals with higher age at death (γ 11 = −0.01), a disability (γ 13 = −0.25), and women (γ 12 = 0.98 for men) exhibited steeper terminal decline.

Table 2.

Growth model for life satisfaction over time-to-death including individual-level and county-level factors

| Variable | Estimate | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| Intercept, π 000 | 44.51* | 1.47 |

| Linear slope, π 100 | −1.44* | 0.18 |

| Quadratic slope, π 200 | −.06* | 0.003 |

| Individual level: intercept | ||

| Age at death, γ 01 | 0.03* | 0.01 |

| Gender, γ 02 | 1.50 | 2.32 |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.47* | 0.06 |

| Disability, γ 04 | −5.52* | 0.32 |

| Individual level: linear slope | ||

| Age at death, γ 11 | −0.01* | 0.00 |

| Gender, γ 12 | 0.98* | 0.31 |

| Disability, γ 13 | −0.25* | 0.04 |

| County level: intercept | ||

| Affluence, π 001 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Proportion of individuals aged 75+, π 002 | 0.12 | 0.20 |

| Care ratio inpatient, π 003 | 5.76* | 2.53 |

| Care ratio outpatient, π 004 | 1.27 | 3.00 |

| Number of inpatient institutions, π 005 | 1702.71* | 863.93 |

| Number of outpatient institutions, π 006 | −314.89 | 281.17 |

| Main task “physical care” inpatient, π 007 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Main task “physical care” outpatient, π 008 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Main task “administration” inpatient, π 009 | 0.16* | 0.06 |

| Main task “administration” outpatient, π 0010 | −0.13 | 0.08 |

| Number private beds, π 0011 | −3.03 | 1.77 |

| Number non-private beds, π 0012 | −27.07 | 17.57 |

| Flexibility in bed provision, π 0013 | −0.01 | 0.08 |

| Capacity, π 0014 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| County level: linear slope | ||

| Proportion of individuals aged 75+, π 101 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Main task “physical care” outpatient, π 104 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Cross-level interactions: level | ||

| Gender × proportion of individuals aged 75+, π 021 | 0.00 | 0.31 |

| Gender × main task “physical care” outpatient, π 022 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Cross-level interactions: slope | ||

| Gender × proportion of individuals aged 75+, π 111 | −0.12* | 0.04 |

| Gender × main task “physical care” outpatient, π 112 | 0.02* | 0.01 |

| Random effects: individual level | ||

| Variance intercept, | 85.18* | 2.45 |

| Variance linear slope, | 0.66* | 0.04 |

| Covariance intercept, linear slope | 4.59* | 0.25 |

| Random effects: county level | ||

| Variance intercept, | 3.83* | 1.01 |

| Variance linear slope, | 0.04* | 0.02 |

| Covariance intercept, linear slope | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Residual variance | 63.20* | 0.58 |

| − 2LL | 230,545 | |

| AIC | 230,618 | |

Unstandardized estimates and standard errors are presented. Scores are standardized to a T metric (M = 50; SD = 10) based on 2002 SOEP sample (M = 6.90, SD = 1.81 on 0–10 scale). AIC Akaike’s information criterion; −2LL = −2 log-likelihood. Intercept is centered at 2 years prior to death. Slopes of change are scaled in T units per year

* p < 0.05

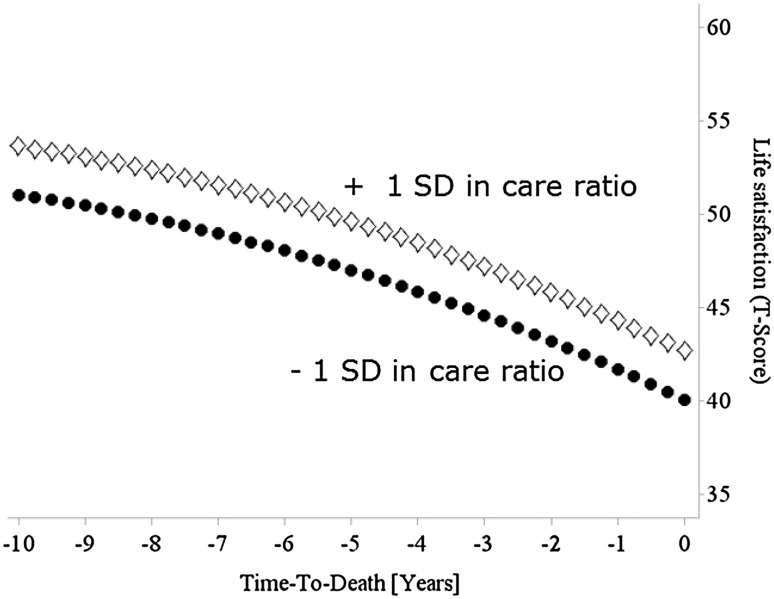

Most important for our question, we found that, after controlling for county-level affluence and demographic decomposition, a number of care provision variables were related to differences in levels of life satisfaction 2 years before death. Level of life satisfaction 2 years prior to death was related to quality, quantity, and expertise of care in inpatient facilities. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 1, residents in counties with higher inpatient facility care ratio (better guidance ratio, lower working load, π 003 = 5.76, p = 0.02) had higher life satisfaction 2 years prior to death. Residents of counties with more inpatient institutions (π 005 = 1702.71, p = 0.04) and/or inpatient facilities with more administrative workers (π 009 = 0.16, p = 0.01) had higher life satisfaction 2 years prior to death. Care ratio in outpatient facilities, number of outpatient institutions, number of employees with main task physical care, number of employees in administration in outpatient facilities, number of private and non-private beds, flexibility in bed provision, and capacity were not associated with levels of well-being 2 years before death.

Fig. 1.

SOEP participants in counties with better care ratio in inpatient facilities (i.e., more staff per resident; diamonds) report higher life satisfaction than those living in counties with worse care ratio (dots). Models covary for key individual (age at death, gender, education, disability) and county (affluence, demographic composition) characteristics

We did not find evidence that healthcare service features are associated with change in life satisfaction. Finally, some significant cross-level interactions suggest that county-level characteristics might moderate or serve as “risk regulators” for how individual-level characteristics influence terminal decline. The moderating positive effect of composition of inhabitants in counties on decline was smaller among men than among women (π 111 = −0.12, p < 0.01, for men). More employees who mainly provided physical care in outpatient institutions contributed to an alleviation of declines among men (π 112 = 0.02, p = 0.03). Taken together, these cross-level interactions suggest, consistent with gender differences in mortality, that some healthcare features differentially influence terminal decline in well-being for men and women.

Discussion

Guided by notions of contextual embedding of individuals (Bronfenbrenner 1979), the major objective of the current study was to examine how regional characteristics relate to late-life well-being. Because care provision becomes an important context in late life, we examined how five aspects of county-level care shape terminal decline in well-being. When controlling for relevant individual and county difference characteristics, results indicate that some county-level care indicators are indeed associated with levels of late-life well-being. In line with Andersen healthcare utilization model (Andersen 1995), participants who lived in counties with better resident-to-staff ratio in inpatient facilities (quality of care) and more inpatient institutions (quantity of care) had higher levels of life satisfaction at the very end of life. In addition, as predicted by the framework for the evaluation of palliative care integration (Bainbridge et al. 2016), individuals living in counties with more staff who mainly works in administration in inpatient facilities (quality of care) reported higher life satisfaction. We take our results to provide some empirical support for long-standing lifespan notions that contextual factors shape select aspects of individual development also at the very end of life and discuss how local care services contribute to late-life well-being trajectories.

County-level healthcare services and late-life well-being

Our findings are consistent with the expectation that a sufficient resident-to-staff ratio enables to fulfill the needs of care recipients (Harrington et al. 2000). If more employees are available per care recipient, this may also prevent employees from becoming easily stressed and overworked and, in turn, undermining residents’ satisfaction (Pekkarinen et al. 2004). This finding also aligns with reports from Kane et al. (2004) who found small associations between better resident-to-staff ratio and quality of life of residents. Interestingly, outpatient facilities’ resident-to-staff ratio was not associated with well-being. We speculate that due to the more diverse nature of outpatient facilities (e.g., number of employees per facility), outpatient service hours, for example, vary a lot between individuals and employees can also spend few but more important time on care recipients. We also found little commonality between indicators of inpatient and outpatient settings (rs .17–.31). It is well possible that measures reflecting qualitative aspects of care are more essential for linking late-life well-being with characteristics of outpatient facilities.

Individuals who lived in counties with more inpatient institutions also had higher levels of well-being than those who lived in counties with fewer inpatient facilities. We speculate that having more inpatient institutions enhances competitions and as a consequence also enhances qualitatively measured performance in these institutions (e.g., ratings by doctors and healthcare experts). On the other hand, although the individuals in our sample are mostly not recipients of care, they might be aware of the better choice between inpatient institutions in their county through healthcare programs or experiences from acquaintances. Because our models covary for affluence (numbers of doctors and GDP in county), we alleviate concerns that this finding is only reflective of county-level differences in wealth and infrastructure. Living in a county with more staff who mainly works in administration in inpatient facilities was associated with higher levels of well-being. This reflects the importance of organization structures in running facilities successfully (Harrington et al. 2000). For example, sufficient employees for administrative tasks ensure that staff who work on the person do not need to care about bureaucracy and sufficient resources in managerial tasks ensure an organized daily procedure (e.g., food supply) in facilities.

None of the healthcare indicators were associated with steeper decline in well-being. There were, however, cross-level interactions indicating that some regional characteristics may work differently for particular segments of the population. Specifically, we found evidence of gender differences, such that men living in counties with greater proportion of older adults reported lower life satisfaction than women living in these counties, and that men living in counties with more staff in outpatient care facilities reported slightly higher levels of life satisfaction than women living in these counties. Explanations include the possibility that older counties provide fewer possibilities for entertainment and activities, a scenario that women may compensate through engagement in social contacts (in the typical gender-role framework), and that men, who generally have smaller social networks, may benefit more from contact with employees in outpatient physical care. Although speculative and exploratory, these differences point to importance of considering diversity of samples and populations being served.

We acknowledge the apparent mismatch between the types of services that were available to decedents and people’s consideration and utilization of such services. We have no information in the data whether people considered these county features in their well-being assessments or made use of the services. At the same time, we would argue that it is rather safe to assume that people indeed make use of such services when needed, particularly when barriers toward using the services (e.g., financial constraints) are low, i.e., in a nation with compulsory healthcare. Our empirical findings can be interpreted as suggesting that knowledge about the existence of appropriate healthcare services is important for people’s level of comfort in a phase of life in which people’s health can quickly worsen. It will be important for future research to examine such speculation and test empirically whether people are actually informed about care services (e.g., closest or best facility) in their living area, be it through the social network, healthcare program, or media, and consider this information in their well-being assessments.

Even though healthcare is compulsory in Germany, informal care provision by family is needed in addition. For example, wealthier families might have more resources (e.g., time, money) to provide informal care. To check the role of income, we ran follow-up analyses and included the latest available pre-government household income for each individual (M = 16,174 euro, SD = 24,570) in the multilevel model reported in Table 2. Household income was not a significant predictor of levels or change of life satisfaction nor did income contribute to cross-level interactions with care variables. We conclude that although personal financial assets might be important for sufficient care amount, the interplay between household income and county-level care provision is not related to development of late-life well-being.

Limitations and outlook

We note several limitations of our study. First, care statistics allow examining quantitative measures of care provision, but do not provide information on quality of care on the healthcare professionals’, the care receivers’, or their relatives’ perception of quality of care. Future studies may be in a position to use measures that healthcare insurances have started to collect, such as those gathering information about the quality of care (e.g., treatment of dementia in the respective care facility) and residents’ evaluations of care. Furthermore, since the introduction of the compulsory German long-term care insurance in 1995 there were tremendous changes in the care service conditions and the year 2001 might not capture the current state of the art. Follow-up analyses revealed that year-to-year rank-order stability for the care indicators considered was high (rs > .85), providing us with some level of confidence that the slowly changing context characteristics can be approximated with time-invariant indicators. The context of care is but one relevant operationalization of regional context. Future research can also examine how environmental features such as parks, daily amenities, and other factors (Voigtländer et al. 2010) shape late-life well-being. As individual-level measures, it would have been highly informative to have information available on personal agency of the individual and their close others, which may be an important factor when deciding whether and how care needs are handled. Moreover, because many care recipients receive informal care through family, information about family constellations and available familial support might help to disentangle whether the lack of significant care indicators might also be (partly) due to potential care provision through family.

Second, some counties only had very few deceased participants and thus might be represented only by few individuals. Follow-up analyses that only included counties with more than seven deceased SOEP participants (n individuals = 4533; n counties = 357) showed substantively the same pattern of results. We also acknowledge that the three-level structure and small number of longitudinal assessments in our data have limited our statistical power to thoroughly estimate individual and county differences in the curvature of late-life decline and predictors thereof. It is also an open question whether our findings generalize to particularly vulnerable segments of the population, such as the very old and those who are in immediate need of receiving assistance with the basic tasks of daily living. For example, for individuals who died at ages 70 and older, characteristics of outpatient institutions might be more important for well-being reports than for those who died from premature deaths (before reaching age 70; OECD, 2011).

Third, development in context also means that context-level variables may change (Clarke et al. 2013). A next step is to use time-varying care characteristics to examine how terminal declines in well-being are shaped by changes in regional service’s availability. One challenge is that county borders also change, with, for example, counties having been being split and then merged with adjacent counties. The Federal Statistical Office (2012) points to the methodological problem of adjacent county services in that, for example, outpatient services might also serve clients from neighbored counties. Future research can investigate how use of outpatient facilities from adjacent counties or moving to an inpatient institution in an adjacent county influences the association between level of regional healthcare and late-life development of well-being.

Counties or their agglomerations have responsibility with respect to care provision in countries such as Germany and the USA (e.g., Medicaid). An initial recommendation for county policies to ensure higher levels of its residents’ well-being in inpatient institutions might be that counties should have a patient-focused care ratio, a sufficient number of institutions, and sufficient administrative staff. However, investigating regions in which individuals live as social-policy structures (county, municipality) neglects that individuals’ use of services might happen in a natural surrounding such as a radius around their home. For example, by geocoding facilities and participants’ residence, regional context might be defined as the number of inpatient institutions within a 25-km radius around people’s residence.

Conclusion

This study examined the role of regional differences in healthcare services for late-life well-being. Using indicators of care services in the counties people lived and died in allowed us to examine how availability of specific features in individuals’ living context shapes late-life levels of and terminal declines in life satisfaction. Our findings provide empirical evidence that county-level inpatient institutions’ number, care ratio, and number of administrative staff shape late-life well-being levels, but not change. As such, our study provides initial suggestions which contextual factors county-level policies need to address to maintain or enhance well-being in the last years of life, but also that more research is needed to reveal the role of regional outpatient institutions and care services role on change in late-life well-being.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the first author’s fellowship in the International Max Planck Research School on the Life Course (LIFE, www.imprs-life.mpg.de), and Grant by the Robert Bosch Stiftung (2012/2013): “Blickwechsel—Junge Forscher gestalten neues Alter”; and Nilam Ram’s contributions were supported by the Penn State Social Science Research Institute and UL TR000127 from the National Institute for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Work on the article was supported by the German Research Foundation (Grant GE 1896/3-1).

Footnotes

Responsible editor: H.-W. Wahl.

Contributor Information

Nina Vogel, Phone: +49-30 2093-9423, Email: nina.vogel@uba.de.

Nilam Ram, Phone: 814-865-7038, Email: nur5@psu.edu.

Jan Goebel, Phone: +49-30 89789-377, Email: jgoebel@diw.de.

Gert G. Wagner, Phone: +49-30 89789-290, Email: gwagner@diw.de

Denis Gerstorf, Phone: +49-30 2093-9422, Email: denis.gerstorf@hu-berlin.de.

References

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Wight RG, Miller-Martinez D, Botticello AL, Karlamangla AS, Seeman TE. Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:52–59. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman L, MacDonald SWS. Death and cognition—viewing a 1962 concept through 2006 spectacles—introduction to the special section. Eur Psychol. 2006;11:161–163. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.11.3.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge D, Brazil K, Ploeg J, Krueger P, Taniguchi A. Measuring healthcare integration: operationalization of a framework for a systems evaluation of palliative care structures, processes, and outcomes. Palliat Med. 2016;30:567–579. doi: 10.1177/0269216315619862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB. On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. Am Psychol. 1997;52:366–380. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann H, Klein T. Love and death in Germany: the marital biography and its effect on mortality. J Marriage Fam. 2004;66:567–581. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00038.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. How does satisfaction with medical care differ by citizenship and nativity status? A county-level multilevel analysis. Gerontologist. 2014;55:gnt201. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P, Morenoff J, Debbink M, Golberstein E, Elliott MR, Lantz PM. Cumulative exposure to neighborhood context: consequences for health transitions over the adult life course. Res Aging. 2013;36:115–142. doi: 10.1177/0164027512470702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenholtz HB, Kane RA, Kane RL, Bershadsky B, Kling KC. Predicting nursing facility residents’ quality of life using external indicators. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:335–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Statistical Office (2012) Care statistics. Care in the framework of care insurance. County comparison 2009 [Pflegestatistik. Pflege im Rahmen der Pflegeversicherung. Kreisvergleich 2009]. Wiesbaden

- Federal Statistical Office (2014) Care statistics 2013. Care in the framework of care insurance. Results in Germany [Pflegestatistik 2013. Pflege im Rahmen der Pflegeversicherung. Deutschlandergebnisse]. Wiesbaden

- Fujita F, Diener E. Life satisfaction set point: stability and change. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:158–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Ram N. Late-life: a venue for studying the mechanisms by which contextual factors influence individual development. In: Whitbourne SK, Sliwinski MJ, editors. Handbook of adulthood and aging. New York: Wiley; 2012. pp. 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Ram N. Inquiry into terminal decline: five objectives for future study. Gerontologist. 2013;53:727–737. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Ram N, Goebel J, Schupp J, Lindenberger U, Wagner GG. Where people live and die makes a difference: individual and geographic disparities in well-being progression at the end of life. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:661–676. doi: 10.1037/a0019574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1650–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guse LW, Masesar MA. Quality of life and successful aging in long-term care: perceptions of residents. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1999;20:527–539. doi: 10.1080/016128499248349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington C, Zimmerman D, Karon SL, Robinson J, Beutel P. Nursing home staffing and its relationship to deficiencies. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55:278–287. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.5.S278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headey B, Muffels R, Wagner GG. Long-running German panel survey shows that personal and economic choices, not just genes, matter for happiness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17922–17926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008612107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL, Bershadsky B, Kane RA, Degenholtz HH, Liu JJ, Giles K, Kling KC. Using resident reports of quality of life to distinguish among nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2004;44:624–632. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.5.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KE, Morenoff JD, House JS. Neighborhood context and social disparities in cumulative biological risk factors. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:572–579. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318227b062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotakorpi K, Laamanen J-P. Welfare state and life satisfaction: evidence from public health care. Economica. 2010;77:565–583. [Google Scholar]

- Kottwitz A. Mode of birth and social inequalities in health: the effect of maternal education and access to hospital care on cesarean delivery. Health Place. 2014;27:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. Competence, environmental press, and the adaptation of older people. In: Lawton MP, Windley PG, Byerts TO, editors. Aging and the environment. New York: Springer; 1982. pp. 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Moss M, Glicksman A. The quality of the last year of life of older persons. Milbank Q. 1990;68:1–28. doi: 10.2307/3350075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H. Social networks and well-being: a comparison of older people in mediterranean and non-mediterranean countries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65:599–608. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE. Long-term disability is associated with lasting changes in subjective well-being: evidence from two nationally representative longitudinal studies. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92:717–730. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland MJ, Smith CA, Toussaint L, Thomas PA. Forgiveness of others and health: do race and neighborhood matter? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:66–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2011) Premature mortality. In: Health at a glance 2011: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:10.1787/health_glance-2011-5-en

- Payne G, Laporte A, Deber R, Coyte PC. Counting backward to health care’s future: using time-to-death modeling to identify changes in end-of-life morbidity and the impact of aging on health care expenditures. Milbank Q. 2007;85:213–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekkarinen L, Sinervo T, Perälä M-L, Elovainio M. Work stressors and the quality of life in long-term care units. Gerontologist. 2004;44:633–643. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.5.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno RA, Wilson-Genderson M, Cartwright FP. The texture of neighborhoods and disability among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:89–98. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Grimm K. Growth curve modeling and longitudinal factor analysis. In: Overton W, Molenaar PCM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: vol 1. Theoretical models of human development. 7. Hoboken: Wiley; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Robichaud L, Durand PJ, Bédard R, Ouellet J-P. Quality of life indicators in long-term care: opinions of elderly residents and their families. Can J Occup Ther. 2006;73:245–251. doi: 10.2182/cjot.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neigborhood effects”: social processes and new directions in research. Ann Rev Sociol. 2002;28:443–478. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc . SAS/STAT user’s guide 9.2. Cary: SAS Institute Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmack U, Oishi S. The influence of chronically and temporarily accessible information on life satisfaction judgments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89:395–406. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippee TP, Henning-Smith C, Kane RL, Lewis T. Resident- and facility-level predictors of quality of life in long-term care. Gerontologist. 2015 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel N, Schilling OK, Wahl H-W, Beekman ATF, Penninx BWJH. Time-to-death-related change in positive and negative affect among older adults approaching the end of life. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:128–141. doi: 10.1037/a0030471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigtländer S, Berger U, Razum O. The impact of regional and neighbourhood deprivation on physical health in Germany: a multilevel study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:403. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl H-W, Schilling O, Oswald F, Iwarsson S. The home environment and quality of life-related outcomes in advanced old age: findings of the ENABLE-AGE project. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6:101–111. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl H-W, Iwarsson S, Oswald F. Aging well and the environment: toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist. 2012;52:306–316. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walshe K, Harrington C. Regulation of nursing facilities in the United States: an analysis of resources and performance of state survey agencies. Gerontologist. 2002;42:475–486. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wight RG, Ko MJ, Aneshensel CS. Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms in late middle age. Res Aging. 2011;33:28–50. doi: 10.1177/0164027510383048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor TD, Fiori KL, Crisp DA. Personal and neighborhood resources, future time perspective, and social relations in middle and older adulthood. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:423–431. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF—the International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]