Abstract

Background/Objective

To determine whether inflammation increases in retina as it does in brain following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), and whether the neurosteroid progesterone, shown to have protective effects in both retina and brain after MCAO, reduces inflammation in retina as well as brain.

Methods

MCAO rats treated systemically with progesterone or vehicle were compared with shams. Protein levels of cytosolic NF-κB, nuclear NF-κB, phosphorylated NF-κB, IL-6, TNF-α, CD11b, progesterone receptor A and B, and pregnane × receptor were assessed in retinas and brains at 24 and 48 h using western blots.

Results

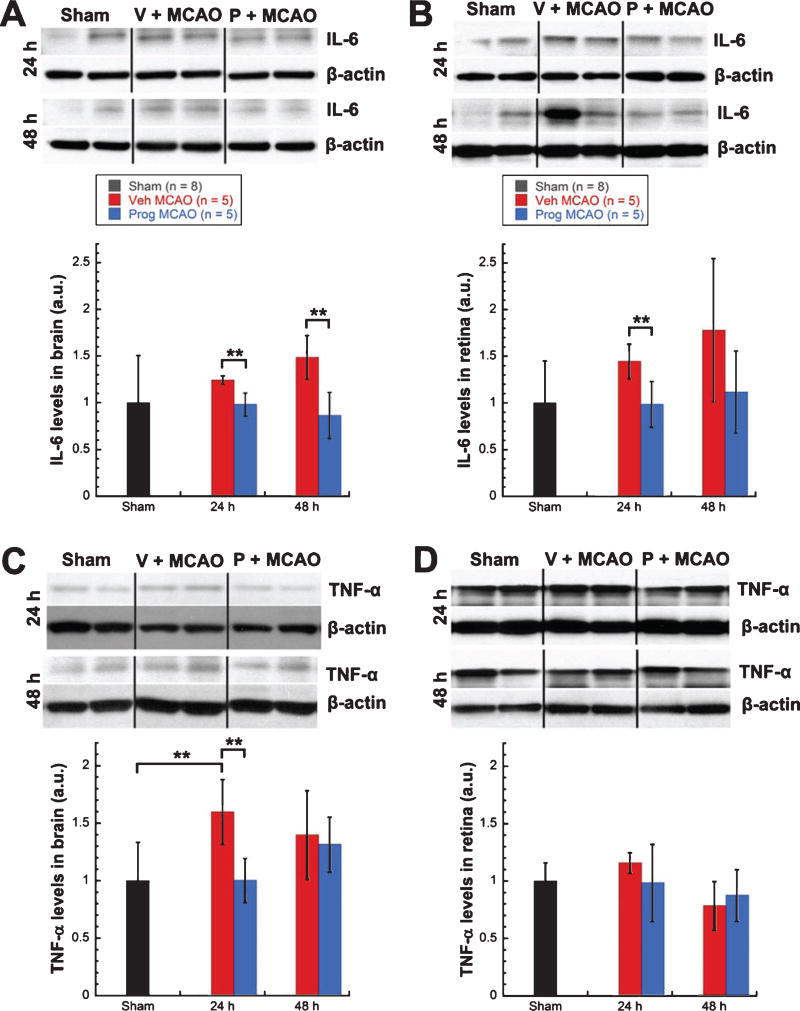

Following MCAO, significant increases were observed in the following inflammatory markers: pNF-κB and CD11b at 24 h in both brain and retina, nuclear NF-κB at 24 h in brain and 48 h in retina, and TNF-α at 24 h in brain.

Progesterone treatment in MCAO animals significantly attenuated levels of the following markers in brain: pNF-κB, nuclear NF-κB, IL-6, TNF-α, and CD11b, with significantly increased levels of cytosolic NF-κB. Retinas from progesterone-treated animals showed significantly reduced levels of nuclear NF-κB and IL-6 and increased levels of cytosolic NF-κB, with a trend for reduction in other markers. Post-MCAO, progesterone receptors A and B were upregulated in brain and downregulated in retina.

Conclusion

Inflammatory markers increased in both brain and retina after MCAO, with greater increases observed in brain. Progesterone treatment reduced inflammation, with more dramatic reductions observed in brain than retina. This differential effect may be due to differences in the response of progesterone receptors in brain and retina after injury.

Keywords: Focal ischemia, inflammation, middle cerebral artery occlusion, NF-kB, progesterone, progesterone receptor, rat, retina, retinal ischemia

1. Introduction

Ocular ischemia can occur as an isolated event or in conjunction with cerebral or systemic disease (Benavente et al., 2001; Hayreh, 1981; Mead et al., 2002; Rumelt et al., 1999). Amaurosis fugax, the transient vision loss that occurs in one or both eyes due to temporary retinal ischemia, is often a first symptom in cerebral stroke (Benavente et al., 2001; Mead et al., 2002; Slepyan et al., 1975), and 57% of strokes are accompanied by visual field defects (Falke et al., 1991). Transient vision loss can also be a sign of impending stroke or arthrosclerosis of the carotid or ophthalmic arteries (Slepyan et al., 1975). When patients with transient retinal ischemia were examined with neurological imaging, 1 in 4 were found to have an acute brain infarct (Helenius et al., 2012). There is also a substantial degree of overlap between mechanisms involved in cerebral stroke and ocular stroke (Allen & Stein, 2014).

Inflammatory responses occur after ischemic injury in both the retina (Dvoriantchikova et al., 2009; Hangai et al., 1996; Hua et al., 2009; Ishizuka et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2012; Schallner et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2006) and the brain (Berti et al., 2002; Gibson et al., 2005; Hill et al., 1999; Ishrat et al., 2010; Schneider et al., 1999; Stephenson et al., 2000; Tu et al., 2010), with the NF-κB pathway playing a key role (Gibson et al., 2005; Ishrat et al., 2010; Tu et al., 2010). Increases in systemic inflammation after cerebral ischemia have been observed as well (Yousuf et al., 2013). Increases in NF-κB pathway activation (Hua et al., 2009; Schneider et al., 1999; Stephenson et al., 2000) and increases in levels of inflammatory cytokines (Berti et al., 2002; Hill et al., 1999) are known to occur in the brain after transient MCAO, a model that causes ischemia in both the brain and the retina (Allen et al., 2014; Block et al., 1997; Steele et al., 2008). A gap in our knowledge is whether these increases in inflammation occur in the retina after MCAO and how they compare with the brain.

The neurosteroid progesterone has beneficial effects in a number of animal models, including traumatic brain injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury (Cutler et al., 2007; Ishrat et al., 2009; Sayeed & Stein, 2009; Schumacher et al., 2007; Stein & Wright, 2010). In these injuries, progesterone treatment has been shown to reduce inflammation, swelling, and neuronal death, and to improve behavioral and functional recovery (Cutler et al., 2007; De Nicola et al., 2013; Ishrat et al., 2010; Ishrat et al., 2009; Schumacher et al., 2007; Yousuf et al., 2013). Specific effects of progesterone on inflammation include reducing TNF-α production by microglia (Drew & Chavis, 2000) and macrophages (Miller & Hunt, 1998), attenuating NF-κB pathway activation after traumatic brain injury (Cutler et al., 2007), and attenuating systemic increases in TNF-α and IL-6 after post-stroke infection (Yousuf et al., 2013). Additionally, progesterone suppresses injury-induced increases in levels of inflammatory markers, including IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and COX-2 after traumatic brain injury (Cutler et al., 2007), TNF-α and IL-6 after cerebral ischemia (Ishrat et al., 2010), and TNF-α, iNOS, and CD11b in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (De Nicola et al., 2013).

Thus far, studies on progesterone treatment in the retina (Doonan et al., 2011; Neumann et al., 2010; Sanchez-Vallejo et al., 2015), and more specifically in retinal ischemia (Allen et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2008), are few, but progesterone’s successes in other models combined with findings of progesterone (Lanthier & Patwardhan, 1986, 1987), progesterone synthesis (Cascio et al., 2007; Coca-Prados et al., 2003; Guarneri et al., 1994; Lanthier & Patwardhan, 1988; Sakamoto et al., 2001), and progesterone receptor (PR) in the eye (Koulen et al., 2008; Li et al., 1997; Swiatek-De Lange et al., 2007; Wickham et al., 2000; Wyse Jackson et al., 2015) make it an attractive candidate for neuroprotective treatment in the retina. Progesterone has also been shown to provide protection in both brain and retina after transient MCAO, however, these protective effects were smaller in the retina than the brain (Allen et al., 2015). Thus, the mechanisms by which progesterone provides protection (including reduction of inflammation) in brain and retina should be further studied to determine why progesterone’s protective effect in brain is greater. Here, we compared the inflammatory response in retina and brain following transient MCAO in rats, and tested progesterone’s effects on this evoked inflammation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 31) from Charles River Laboratories were used in this study. At the time of MCAO surgery, rats were approximately 60 days of age (290–330 grams). Littermates that received sham surgeries (incisions in the scalp and neck) and vehicle injections were used as controls. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Emory University protocol #20001517) and performed in accordance with NIH guidelines and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Rats were housed under a 12 : 12 reverse light:dark cycle with water and food ad libitum and handled daily for at least 5 days prior to surgery. Two rats died during surgery, and one was excluded due to an incomplete reperfusion.

2.2. MCAO surgery

MCAO surgery was performed as described previously with minor modifications (Longa et al., 1989). Briefly, inhalation of 5% isoflurane (in a N2/O2 70%/30% mixture) was used to anesthetize the animals with an inhalation of 2% isoflurane to maintain sedation. Blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) was analyzed and sustained at 90% using a pulse oximeter (SurgiVet, model V3304; Waukesha, WI, USA). Body temperature was maintained between 36.5°C and 37.5°C. Laser-Doppler flowmetry (LDF) was used to monitor cerebral blood flow, as it has been shown previously to be practical and reliable in detecting changes in cerebral blood flow during focal cerebral ischemia (Dirnagl et al., 1989). To reduce variability and ensure relative uniformity of the ischemic insult, animals with mean ischemic cerebral blood flow greater than 40% of baseline LDF were excluded. An LDF probe (Moor Instruments, Wilmington, Delaware, USA)was inserted over the ipsilateral parietal cortex to monitor blood flow from 5 minutes prior to occlusion to 5 minutes after reperfusion.

At the ventral surface of the neck, a midline incision was made and the right common carotid arteries were separated and ligated using a 6.0 silk suture. Next, the internal carotid and pterygopalatine arteries were occluded using a microvascular clip to allow insertion of a 4-0 silicon-coated monofilament (0.35–0.40 mm long) (Doccol Co., Albuquerque, NM, USA) through an incision in the external carotid artery. The filament was slid into the internal carotid artery and gently pushed an estimated 20 mm distal to the carotid bifurcation, where it blocked the openings to both the middle cerebral and ophthalmic arteries. The filament was removed after 120 minutes, at which time reperfusion occurred. Then the wound was sutured, and rats were transferred to a heating blanket until they recovered from anesthesia.

2.3. Progesterone preparation and dosing

Progesterone was made in stock solutions using 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HBC; 25% w/v solution in H2O; a non-toxic aqueous solution that dissolves progesterone) as the solvent. An 8 mg/kg progesterone dose was used as this has been shown to be most protective after stroke (Wali et al., 2014). Progesterone and vehicle treatments were administered intraperitoneally at 1 h post injury, and then subcutaneously at 6 h post for the 24-h group and 6 and 24 h for the 48-h group. In all experiments, the rats’ group identity was coded with regard to surgery and treatment to prevent experimenter bias.

2.4. Biochemical evaluation

Rats were euthanized by overdose of Pentobarbital and their eyes enucleated. Retinas and the penumbral portion of the brain were dissected out for use in western blots. Isolated tissue was frozen immediately on dry ice. The NE-PER kit (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) was used to homogenize the tissue and separate it into nuclear and cytosolic fractions. Western immunoblotting was used to assess brain and retina protein levels of pNF-κB, nuclear and cytosolic NF-κB, IL-6, TNF-α, CD11b, PR-A, PR-B, and PXR (see Table 1 for details on antibodies). Protein samples were run on 4–20%Tris-Glycine Criterion Pre-cast TGX gels at 90 V for approximately 2 h (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane at 30 V overnight and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in a 5% BSA/TBS-Tween blocking solution. Blots were then incubated in primary antibody for two nights at 4°C. Blots were rinsed with TBS-Tween prior to incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were rinsed with TBS-Tween again before a 1-minute incubation in a chemiluminescent solution. Bands were detected using films, scanned, and analyzed using densitometry. Blots were stripped and β-Actin and Histone H3 were used as loading controls for cytosolic blots and nuclear blots, respectively (note: all blots are from cytosolic fraction unless specified as nuclear). Twenty-four-hour data was normalized to 24-h shams, and 48-h data was normalized to 48-h shams. The 24- and 48-h sham groups were pooled because there were no significant differences between these groups.

Table 1.

Detailed information on antibodies used in this study

| Antibody | Molecular Weight | Dilution | Company | Product # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mouse anti-pNF-κB p65 | 65 kDa | 1 : 2000 | Cell Signaling | 3036 |

| rabbit anti-NF-κB p65 | 65 kDa | 1 : 5000 | Cell Signaling | 8242S |

| rabbit anti-IL-6 | 21–28 kDa | 1 : 5000 | Abcam | Ab6672 |

| rabbit anti-TNF-α | 23 kDa | 1 : 1000 | Abcam | Ab66579 |

| rat anti-CD11b | 128 kDa | 1 : 1000 | Serotec | MCA 275 |

| rabbit anti-PR | PR-A 81 kDa | 1 : 1000 | Santa Cruz | SC-539 |

| PR-B 116 kDa | ||||

| goat anti-PXR | 50 kDa | 1 : 1000 | Santa Cruz | SC-7739 |

| rabbit anti-Histone H3 | 17 kDa | 1 : 1000 | Cell Signaling | 9715L |

| mouse anti-β-actin | 47 kDa | 1 : 5000 | Sigma | A2228 |

2.5. Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were analyzed using multiple unpaired, two tailed t-tests (four per marker) with the alpha level corrected for with false discovery rate (p < 0.031) (Storey, 2003), thus requiring us to employ a more stringent alpha cut off than the commonly used 0.05. Mann-Whitney Rank Sum tests were used for groups that failed the normality test.

3. Results

3.1. NF-κB pathway activation increased in both brain and retina following MCAO and progesterone attenuated this increase

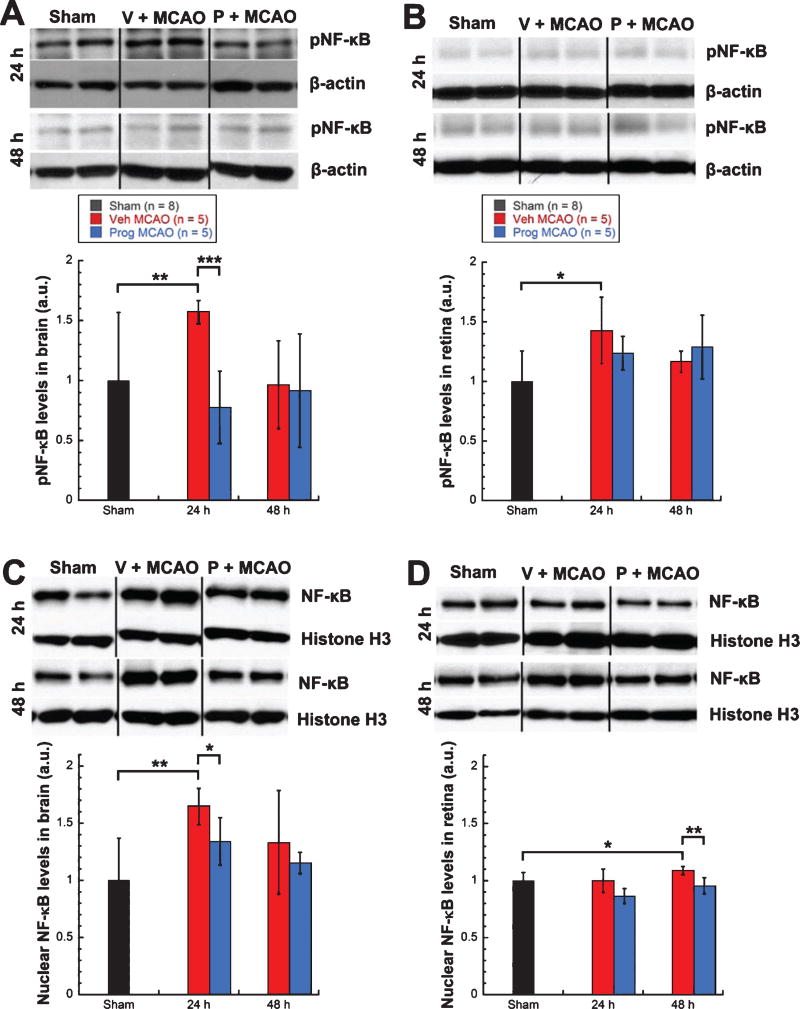

Levels of phosphorylated NF-κB (pathway active) showed significant increases in brains (57%, Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test, T = 54.00, p < 0.01) and retinas (43%, unpaired t-test, t = −2.834, p < 0.03) from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8) at 24 h post-injury (Fig. 1A, 1B). Levels of phosphorylated NF-κB were significantly lower in brains from progesterone- vs. vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5/group) at 24 h post-MCAO (−79%, unpaired t-test, t = 5.601, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1A), with retinas showing a trend for lower levels (−19%, Fig. 1B). Levels of nuclear NF-κB (pathway active) showed significant increases in brains (65%, unpaired t-test, t = −3.667, p < 0.01) at 24 h post-MCAO (Fig. 1C) and retinas (9%, unpaired t-test, t = −2.534, p < 0.03) at 48 h post-MCAO in vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8) (Fig. 1D). For progesterone- vs. vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5/group), levels of nuclear NF-κB were significantly lower in brains at 24 h (−31%, unpaired t-test, t = 2.615, p < 0.03) (Fig. 1C) and retinas at 48 h (−13%, unpaired t-test, t = 3.774, p < 0.01) (Fig. 1D). Levels of cytosolic NF-κB (pathway suppressed) showed a trend for a decrease (22%) in brains from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8) at 48 h post injury (Fig. 1E), with retinas showing a significant decrease at 48 hours (22%, unpaired t-test, t = 8.415, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1F). For progesterone- vs. vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5/group), brains showed significantly higher levels of cytosolic NF-κB at 24 h post-injury (+8%, unpaired t-test, t = −3.681, p < 0.01) and a trend for higher levels at 48 h post injury (+21%, Fig. 1E), with retinas showing significantly higher levels at 48 h (+12%, unpaired t-test, t = −3.041, p < 0.03) (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Increased NF-κB pathway activation in brain and retina following MCAO was attenuated by progesterone treatment. Phosphorylated NF-κB expression in brain (A) and retina (B). Nuclear NF-κB expression in brain (C) and retina (D). Cystosolic NF-κB expression in brain (E) and retina (F). Expression of NF-κB pathway markers as determined by western blot and quantified by densitometry. Bands were normalized to the appropriate loading control (β-Actin for cytosolic blots and Histone H3 for nuclear blots). Results expressed as means ± SD. * = p<0.03; ** = p<0.01; *** = p < 10.001.

3.2. IL-6, TNF-α, and CD11b increased in both brain and retina following MCAO and progesterone attenuated these increases

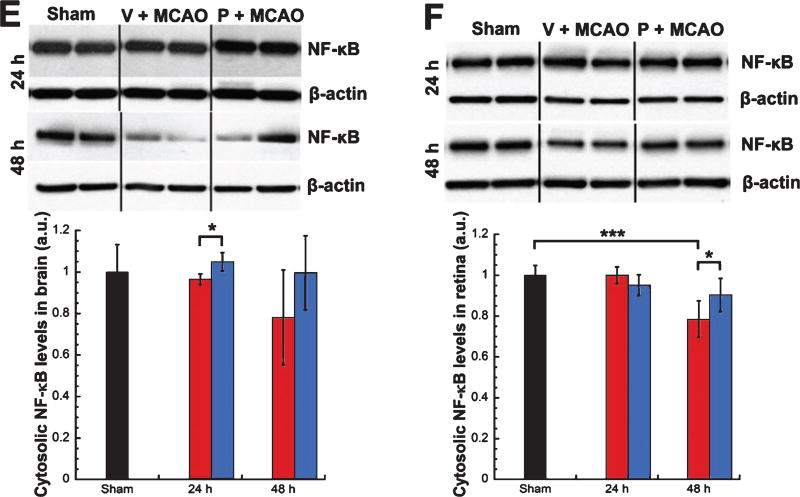

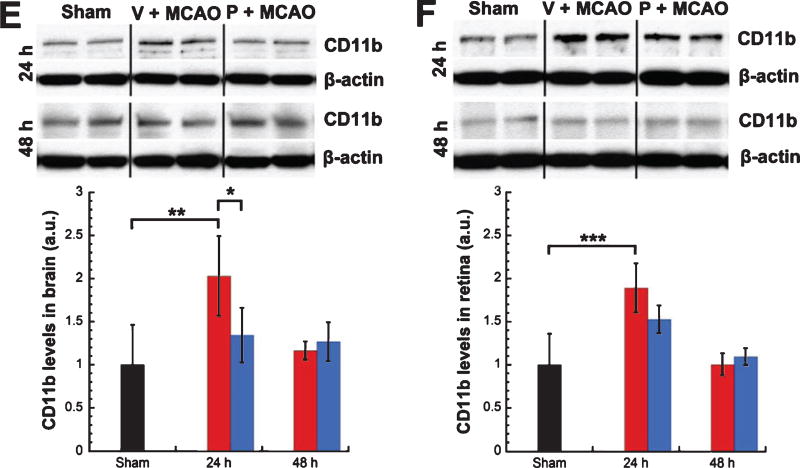

Levels of IL-6 showed a trend for increases in brains (24% at 24 h; 48% at 48 h) (Fig. 2A) and retinas (44% at 24 h; 79% at 48 h) (Fig. 2B) from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8). For progesterone- vs. vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5/group), levels of IL-6 were significantly lower in brains at both 24 (−26%, unpaired t-test, t = 4.424, p < 0.01) and 48 h (−62%, unpaired t-test, t = 4.070, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2A) post-injury and in retinas at 24 h (−46%, unpaired t-test, t = 3.350, p < 0.01), with 48-h retinas from progesterone-treated rats showing a trend for lower IL-6 levels (−61%) (Fig. 2B). Levels of TNF-α showed significant increases in brains at 24 h (60%, unpaired t-test, t = −3.330, p < 0.01) with a trend for an increase at 48 h (40%) for vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8) (Fig. 2C). Retina levels of TNF-α showed a trend for an increase for vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8) at 24 h (16%) (Fig. 2D). Levels of TNF-α were significantly lower in brains from progesterone- vs. vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5/group) at 24 hours post-MCAO (−60%, unpaired t-test, t = 3.918, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2C), with retinas showing a trend for lower levels at 24 hours (−17%) (Fig. 2D). Levels of CD11b showed significant increases in brains (103%, unpaired t-test, t = −3.903, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2E) and retinas (89%, unpaired t-test, t = −4.690, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2F) from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8) at 24 h post injury, with 48-h brains showing a trend for an increase (16%). Levels of CD11b were significantly lower in brains from progesterone- vs. vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5/group) at 24 h post-MCAO (−69%, unpaired t-test, t = 2.738, p < 0.03) (Fig. 2E), with retinas showing a trend for lower levels at 24 h (−36%) (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Increased cytokine levels in brain and retina following MCAO were attenuated by progesterone treatment. IL-6 expression in brain (A) and retina (B). TNF-α expression in brain (C) and retina (D). CD11b expression in brain (E) and retina (F). Expression of inflammatory markers as determined by western blot. Bands were quantified by densitometry and normalized to β-Actin loading controls. Results expressed as means ± SD. * = p < 0.03; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001.

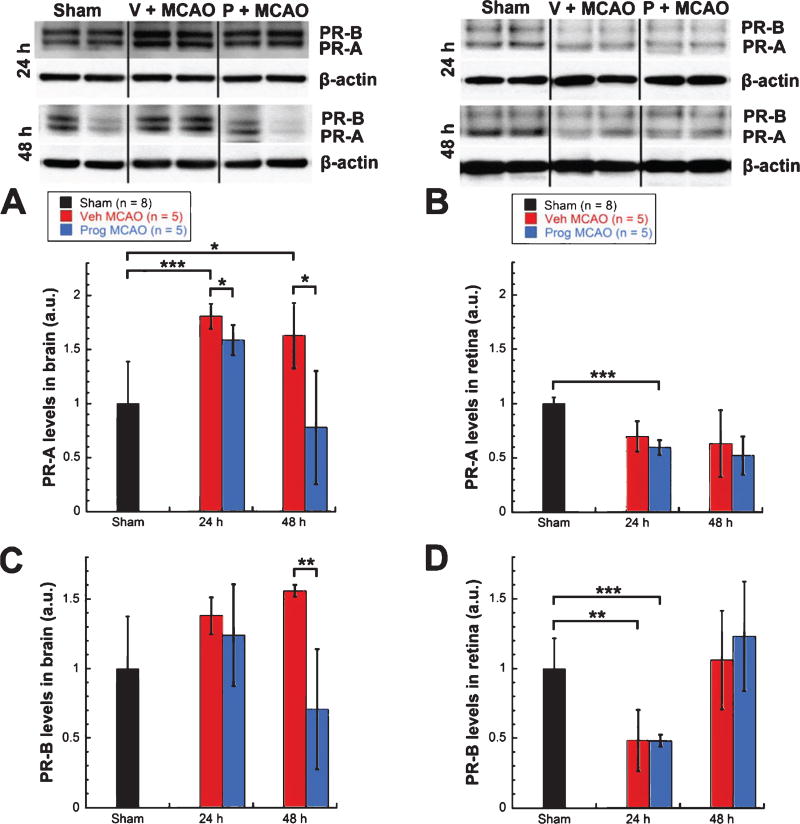

3.3. Progesterone receptor is upregulated in the brain and downregulated in the retina after MCAO

Levels of PR-A showed significant increases in brains from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) vs. shams (n = 8) at both 24 (81%, unpaired t-test, t = −4.439, p < 0.001) and 48 h (63%, unpaired t-test, t = −3.061, p < 0.03) post-MCAO (Fig. 3A). In contrast, levels of PR-A showed a trend for decreases in retinas from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) vs. shams (n = 8) at 24 (30%) and 48 (37%) h post injury (Fig. 3B). Progesterone-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) showed significantly lower levels of PR-A in the brain compared with vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) at both 24 (−22%, unpaired t-test, t = 2.711, p < 0.03) and 48 (−85%, unpaired t-test, t = 3.149, p < 0.03) h post-injury (Fig. 3A). However, progesterone treatment did not change the PR-A reduction observed in retinas in either direction (Fig. 3B). Levels of PR-B showed a trend for increases in brains from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8) at 24 (38%) and 48 (56%) h post-injury, with brains from progesterone- vs. vehicle-treated animals (n = 5/group) showing a trend for lower levels at 24 h (−14%) and significantly lower levels at 48 h post injury (−85%, unpaired t-test, t = 3.369, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3C). In contrast, levels of PR-B showed significant decreases in retinas from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) vs. shams (n = 8) at 24 h post injury (52%, unpaired t-test, t = 4.132, p < 0.01), and progesterone treatment did not change this reduction (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Progesterone receptor was upregulated in brain and downregulated in retina after MCAO. PR-A expression in brain (A) and retina (B). PR-B expression in brain (C) and retina (D). Expression of inflammatory markers as determined by western blot. Bands were quantified by densitometry and normalized to β-Actin loading controls. Results expressed as means ± SD. * = p < 0.03; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001.

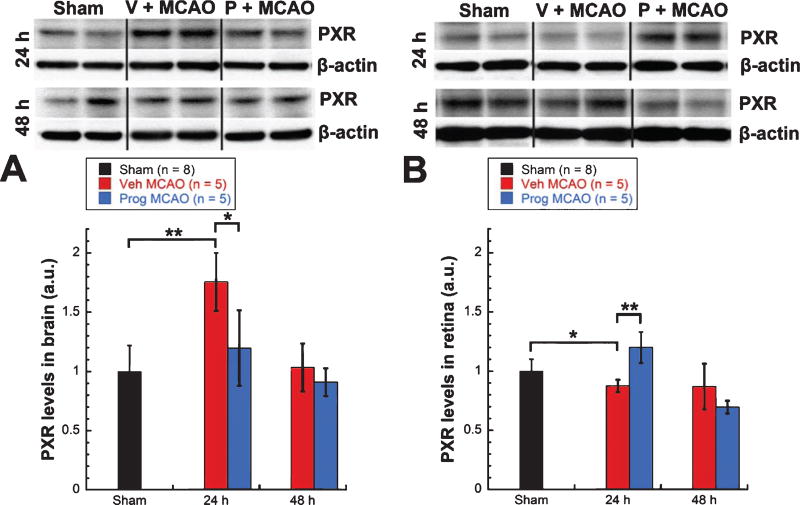

3.4. PXR was upregulated in brain but downregulated in retina after MCAO

At 24 h post-MCAO, levels of PXR showed a significant increase in brains from vehicle-treated MCAO rats (n = 5) over shams (n = 8, 75%, Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test, T = 55.000, p < 0.01) (Fig. 4A) and a significant decrease in retinas (13%, unpaired t-test, t = 2.508, p < 0.03) (Fig. 4B). Progesterone treated rats (n = 5) showed significantly lower levels of PXR in brain (−56%, unpaired t-test, t = 3.110, p < 0.03) (Fig. 4A) and significantly higher levels of PXR in retinas (+33%, unpaired t-test, t = −5.129, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B) at 24 h compared with vehicle-treated rats (n = 5).

Fig. 4.

PXR was upregulated in brain but downregulated in retina after MCAO. PXR expression in brain (A) and retina (B). Expression of inflammatory markers as determined by western blot. Bands were quantified by densitometry and normalized to β-Actin loading controls. Results expressed as means ± SEM. * = p < 0.03; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

4.1. NF-κB pathway activation after retinal ischemia

Previous evidence of NF-κB pathway activation after retinal ischemia includes increases in protein levels of phosphorylated NF-κB (Ishizuka et al., 2013; Schallner et al., 2012), increases in NF-κB DNA binding activity (Schallner et al., 2012), increases in mRNA levels of NF-κB (Jiang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2006), increases in protein levels of NF-κB in the nucleus (Jiang et al., 2012), and increases in numbers of NF-κB positive cells in the retina (Wang et al., 2006). Additionally, selective inactivation of the NF-κB pathway in astrocytes was shown to be protective in retinal ischemia (Dvoriantchikova et al., 2009). Following retinal ischemia, increased mRNA levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were observed (Hangai et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2006), as well as increases in IL-6 positive cells (Wang et al., 2006). NF-κB inhibition resulted in significantly reduced expression of pro-inflammatory genes like TNF-α, and completely suppressed the upregulation of IL-6 that follows retinal ischemia (Dvoriantchikova et al., 2009). While some suggest that complete inhibition of NF-κB could exacerbate retinal injury (Jiang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2006), Dvoriantchikova and colleagues (2009) concluded that it is chronic NF-κB activation in astrocytes and microglia, rather than NF-κB activation in general, that is problematic following retinal ischemia.

Similarly, in the transient MCAO model we found increases in NF-κB pathway activation and increases in levels of inflammatory markers in the retina. Increases in inflammation in the brain have previously been shown to occur after cerebral ischemia (Berti et al., 2002; Gibson et al., 2005; Hill et al., 1999; Hua et al., 2009; Ishrat et al., 2010; Schneider et al., 1999; Stephenson et al., 2000; Tu et al., 2010), and our results confirm those findings. Our previous work has shown that, functionally, the retina is less susceptible than the brain to ischemia induced by the transient MCAO model (Allen et al., 2014), and our results here show smaller increases in inflammation in retina vs. brain (Table 2). Previously, we showed that the retina was less susceptible to the ischemic damage caused by MCAO than the brain, with greater cell death and more lasting functional deficits occurring in the brain (Allen et al., 2014). Steele et al. (2008) showed that during MCAO almost no retinal perfusion occurs, so this difference in susceptibility is likely not due to a difference in levels of occlusion. The retina has been shown to have a greater tolerance time for ischemic injury in general (8–97 minutes, depending on model and species (Hayreh & Weingeist, 1980; Stowell et al., 2010)) than the brain (3–7 minutes, depending on model and species (Brock, 1956; Kabat H, 1941; Meyer, 1956; Weinberger L, 1940)), and this is likely due to relative ease of reperfusion in the retina as well as nutrient stores in the retina and vitreous (Hayreh & Weingeist, 1980).

Table 2.

Summary of changes in inflammatory markers expressed as % difference in vehicle-treated MCAO animals over sham

| Brain | Retina | |

|---|---|---|

| pNF-κB | +57% at 24 h | +43% at 24 h |

| nuclear NF-κB | +65% at 24 h | |

| +33% at 48 h | +9% at 48 h | |

| cytosolic NF-κB | −22% at 48 h | −10% at 48 h |

| IL-6 | +24% at 24 h | +44% at 24 h |

| +48% at 48 h | +79% at 48 h | |

| TNF-α | +60% at 24 h | +16% at 24 h |

| +40% at 48 h | ||

| CD11b | +103% at 24 h | +89% at 24 h |

| +16% at 48 h |

Larger increases were observed in brain vs. retina. Bold = p < 0.03.

4.2. Greater protection with progesterone was observed in brain vs. retina

Progesterone has been shown to provide protection in a number of animal models (Cutler et al., 2007; De Nicola et al., 2013; Gonzalez Deniselle et al., 2005; Guennoun et al., 2008; Hua et al., 2009; Yousuf et al., 2013). Despite the very large literature supporting the beneficial effects of progesterone in pre-clinical research, and in Phase II clinical trials for traumatic brain injury (Wright et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2008), two almost identical Phase III trials testing the hormone as a treatment for moderate to severe traumatic brain injury did not show efficacy (Skolnick et al., 2014; Wright et al., 2014). Unfortunately, both trials suffered from a number of major methodological problems, including suboptimal dosing parameters (Howard et al., 2015) and the use of outcome measures that may have been too blunt to reveal benefit across a very wide spectrum of TBI conditions (Stein, 2015).

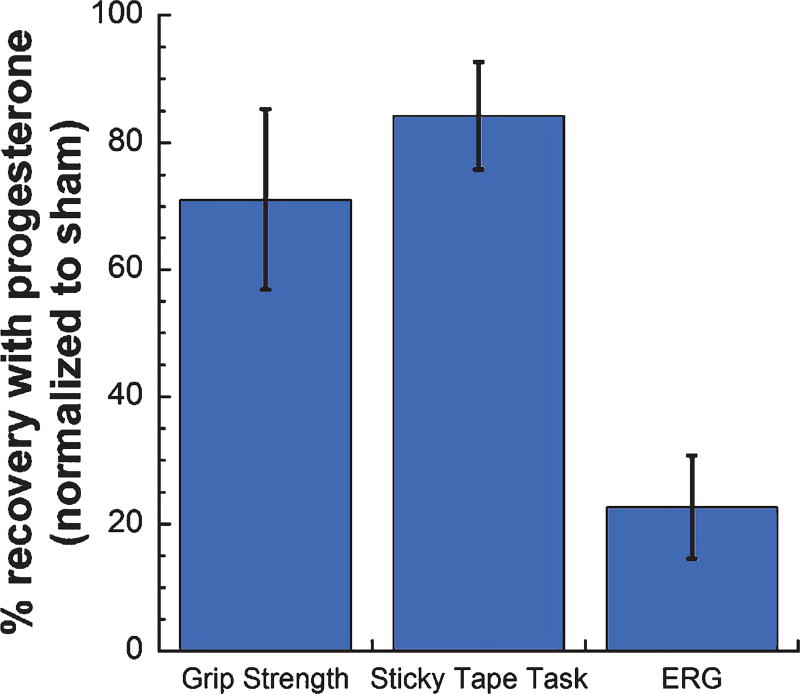

Progesterone has been observed to reduce glial activation and cytokine production both in vitro and in vivo (De Nicola et al., 2013; Drew & Chavis, 2000; Miller & Hunt, 1998) and to reduce NF-κB pathway activation after traumatic brain injury (Cutler et al., 2007). In models of cerebral ischemia, progesterone has been shown to reduce inflammation both in the brain and systemically, to decrease infarct size, and to improve functional recovery (Hua et al., 2009; Ishrat et al., 2010; Yousuf et al., 2013). Our results confirm previous findings of progesterone protection in cerebral ischemia, showing that progesterone attenuated ischemia-induced increases in NF-κB pathway activation and inflammatory markers in the brain. Additionally, we show here that progesterone reduces inflammation in the retina following transient MCAO. Interestingly, more dramatic protection with progesterone treatment following MCAO was observed in brain vs. retina. We observed greater reductions in NF-κB pathway markers and inflammatory cytokines with progesterone treatment in brain vs. retina (Table 3). In a previous study, we demonstrated retinal injury after MCAO and progesterone protection against this retinal ischemic injury using a variety of measures, including functional deficits on electroretinogram, retinal ganglion cell death, and increased GFAP and glutamine synthetase levels (Allen et al., 2015; Allen et al., 2014). However, while progesterone treatment significantly improved function on behavioral tests (71–84% recovery), less improvement was observed in retinal function as measured by the electroretinogram (23% recovery) (Figure 5) (Allen et al., 2015), which mirrors our observation here that progesterone treatment resulted in greater reductions in inflammatory markers in the brain than the retina.

Table 3.

Summary of changes in inflammatory markers between progesterone- and vehicle-treated MCAO animals expressed as % difference between progesterone- and vehicle-treated rats over sham

| Brain | Retina | |

|---|---|---|

| pNF-κB | −79% at 24 h | −19% at 24 h |

| nuclear NF-κB | −31% at 24 h | −13% at 48 h |

| −18% at 48 h | ||

| cytosolic NF-κB | +8% at 24 h | +12% at 48 h |

| +21% at 48 h | ||

| IL-6 | −26% at 24 h h | −46% at 24 h |

| −62% at 48 h | −61% at 48 h | |

| TNF-α | −60% at 24 h | −17% at 24 h |

| CD11b | −69% at 24 h | −36% at 24 h |

Greater protective effects were observed with progesterone treatment in brain vs. retina. Bold = p < 0.03.

Fig. 5.

Progesterone treatment after MCAO resulted in greater improvement on tests of behavioral function (Grip Strength and Sticky Tape Tasks) vs. retinal function (electroretinogram; ERG). Results are normalized to sham and expressed as % recovery with progesterone, means ± SD. These data were reanalyzed from behavioral data presented in Allen et al., 2015, so that we could determine whether progesterone’s effects on behavioral vs. retinal function concurred with the larger reductions in inflammatory markers observed in brain vs. retina in progesterone-treated MCAO rats (Allen et al., 2015).

4.3. Differences in PR expression in retina and brain may contribute to differences in responsiveness to progesterone treatment

Progesterone and PR have been identified in both brain (Camacho-Arroyo et al., 1994; Guerra-Araiza et al., 2002; Guerra-Araiza et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2012; Meffre et al., 2007) and retina (Koulen et al., 2008; Lanthier & Patwardhan, 1988;Wickham et al., 2000), and progesterone synthesis occurs in both tissues (Cascio et al., 2007; Cherradi et al., 1995; Coca-Prados et al., 2003; Guarneri et al., 1994; Lanthier & Patwardhan, 1988; Sakamoto et al., 2001; Tsutsui, 2006; Tsutsui et al., 2000). PR mRNA has been found in retina samples in rats and rabbits (Wickham et al., 2000). Protein levels of classical PRs (Koulen et al., 2008; Wyse Jackson et al., 2015), as well as membrane PRs and PR membrane components (Wyse Jackson et al., 2015), have been shown to be expressed in mouse retina. Here, we show that PR-A and PR-B are expressed at the protein level in rat retina, and that receptor levels are reduced at 24 h post-injury. In brain, however, we observed an increase in PR-A and PR-B after injury. This difference in PR levels may contribute to the greater effects of progesterone observed in the brain versus retina. With progesterone treatment, we see no change in PR expression in the retina but a reduction in PR expression in the brain at 48 h.

Progesterone levels are known to increase in serum after traumatic brain injury in humans (Wagner et al., 2011), in brain after traumatic brain injury in rats (Meffre et al., 2007), and in serum and brain after transient MCAO in mice (Liu et al., 2012). Progesterone levels also increase in response to inflammation and glucose deprivation (Elman & Breier, 1997; Zitzmann et al., 2005). Relatively little is known about how classical PRs respond after neural injury. Increases in PR-A and PR-B expression were observed in brains in an animal model of intra-uterine growth restriction (Palliser et al., 2012). However, another study did not show changes in levels of PR mRNA in brain after transient MCAO with or without progesterone treatment (Dang et al., 2011). These results in the MCAO model conflict with our own, but this may be due to an mRNA vs. protein difference. Decreases in PR expression were observed after spinal cord injury, and these decreases did not change with progesterone treatment (Labombarda et al., 2003). These findings in spinal cord mirror our findings in retina, possibly suggesting a difference in PR behavior in the brain vs. other neural tissue following injury. However, a recent study in a retinal degeneration model showed stable levels of PR-A and PR-B, but increased levels of PR membrane component 1 (PGRMC 1), with retinal degeneration (Wyse Jackson et al., 2015), which may suggest that injury model is also important in receptor behavior.

Studies have shown examples of both PR-dependent and PR-independent mechanisms with progesterone treatment in several different injury models. For example, progesterone treatment induced remyelination of demyelinated axons (Ghoumari et al., 2005) and protected against motorneuron loss in injured spinal cord slices (Labombarda et al., 2013) in wildtype mice but not PR knock-out mice, suggesting PR dependence. In the transient MCAO model, PR knock out mice and heterozygotes were shown to have increased susceptibility to ischemic brain injury. In PR knock-out mice, PR mRNA is completely absent, and in PR heterozygotes, PR mRNA levels in the cortex, subcortical regions, and hypothalamus are decreased by approximately 60% (Liu et al., 2012). The finding that PR heterozygotes show diminished responses to progesterone treatment (Ghoumari et al., 2003; Hussain et al., 2011) suggests that levels of PR, and not simply PR presence, are important in the response to progesterone treatment post-injury. In both the transient MCAO and the spinal cord injury experiments, treatment with allopregnanolone, a metabolite of progesterone, still had a protective effect in PR knock-out mice (Labombarda et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2012). Allopregnanolone acts independently of the progesterone receptor by binding directly to the GABAA receptor complex and acting as a positive allosteric modulator, increasing Cl− influx and reducing excitability (Reddy et al., 2005). Perhaps allopregnanolone treatment would prove more effective in the retina. Another option would be to perform a dose response curve to determine the optimal progesterone dose and treatment duration, which may differ for the retina versus the brain. Different progesterone doses have proven more effective in different injury models in the brain: 8 mg/kg progesterone for stroke (Wali et al., 2014) and 16 mg/kg for traumatic brain injury (Cutler et al., 2007). Finally, combination therapy with progesterone and Vitamin D, which was shown produce greater reductions in phosphorylation of NF-κB after traumatic brain injury than either agent alone (Tang et al., 2015), may also provide greater protection against retinal inflammation, especially given that Vitamin D deficient animals show increased inflammation (Cekic et al., 2011).

A few possibilities could explain the reduction in PR expression in brain following progesterone treatment. 1) Under normal conditions, PR expression is down-regulated by progesterone treatment in estradiol-inducible areas, including the hypothalamus and some limbic structures, but not in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves (Camacho-Arroyo et al., 1994; Guerra-Araiza et al., 2002; Guerra-Araiza et al., 2003; Jung-Testas et al., 1996; Labombarda et al., 2003). Because the areas damaged in transient MCAO (cerebral cortex and striatum) have been shown not to have PR expression affected by progesterone treatment (cortex) (Camacho-Arroyo et al., 1994; Guerra-Araiza et al., 2002) or have been shown not to be estradiol-inducible areas (striatum) (Parsons et al., 1982), the reduction in PR is probably not caused by a down-regulating effect of progesterone treatment. 2) Our western blots examined PR expression in the cytosolic fraction, and it is possible that these receptors translocated to the nucleus when activated by progesterone. PRs in areas of the brain involved in reproduction (i.e., hypothalamus) generally respond to progesterone binding by forming dimers and translocating to the nucleus (Schumacher et al., 2013). However, much of the PRs in other brain areas are expressed in axons, dendrites, and synapses (not near the nucleus) (Waters et al., 2008) and are thought to act in the cytoplasm or at the plasma membrane by activating kinases or interacting with intracellular signaling pathways (Bagowski et al., 2001; Boonyaratanakornkit et al., 2008; Faivre et al., 2008; Faivre & Lange, 2007; Maller, 2001). 3) Thus, we think it is most likely that PR expression is reduced in progesterone-treated ischemic tissue because progesterone treatment has restored the tissue to a more “normal” condition.

4.4. PXR expression in brain vs. retina following transient MCAO

In addition to acting through PRs, progesterone and its metabolites have been shown to bind to and influence the activity of other receptors, including glucocorticoid (Svec et al., 1989; Svec et al., 1980), acetylcholine (Valera et al., 1992), GABAA (Puia & Belelli, 2001; Reddy et al., 2005), Sigma-1 (Maurice et al., 1998), and pregnane × receptors (Kliewer et al., 1998; Langmade et al., 2006). PXR activates p-Glycoprotein (P-gp), an efflux pump implicated in the removal of cytotoxic and xenobiotic substances in both the blood-brain and blood-retina barriers (Bauer et al., 2004; Zhang, Lu, et al., 2012). PXR has previously been identified in brain capillaries (Bauer et al., 2004) and retinal pigmented epithelium (Zhang, Li, et al., 2012; Zhang, Lu, et al., 2012). The literature on PXR expression after injury is not consistent (Chen et al., 2011; Hartz et al., 2010; Souidi et al., 2005).

Here, we show increased levels of PXR in brain at 24 h post-MCAO, with progesterone treatment resulting in “normal” levels of PXR. Conversely, in retina we observed lower levels of PXR at 24 h post-injury, and PXR levels increased with progesterone treatment.

Although the retina is an extension of the brain, there are differences in gene and protein expression in each tissue. For example, the retina expresses large quanties of rhodopsin (McGinnis et al., 1986), and the brain and retina express different neuropeptides and G-coupled protein receptors (Akiyama et al., 2008). In this case, PXR is differentially expressed, particularly under injury conditions, and possibly the reduced protection in the retina with progesterone is due in part to the reduced PXR expression. Our findings may also be taken to support the hypothesis that the brain, given its much more extensive neuronal networking systems, and its capacity to reorganize, interpret, and synthesize visual perception, may have need for a higher density of PXR receptors and may also have mechanisms in place to increase levels of PXR after injury.

In the acute period after MCAO, a number of changes occur in the blood brain barrier, leading to compromised vascular integrity and increased permeability. Progesterone treatment has been shown to attenuate blood brain barrier disruption in models of permanent and transient MCAO, possibly through effects on VEGF, matrix metalloproteinases, and tight junction proteins (Ishrat et al., 2010; Won et al., 2014). It is possible that the early increased levels of PXR after MCAO and the attenuation of this increase with progesterone are associated with progesterone’s protective effects on blood brain barrier integrity.

In our model of ischemic injury, we can suggest that by upregulating PXR in the retina, progesterone treatment might reduce some of the oxidative stress caused by the injury – a known effect of PXR activation (Swales et al., 2012; Zucchini et al., 2005). More research is needed to determine the role of PXR after injury and with progesterone treatment, particularly with respect to vascular integrity.

4.5. Conclusions

Following MCAO, inflammation increased in both brain and retina, with greater increases occurring in brain. Inflammation was reduced post-MCAO with progesterone treatment, and more dramatic protective effects of progesterone were observed in brain than retina. Levels of PR were upregulated in brain but downregulated in retina after MCAO, which could explain why we see more robust progesterone protection in brain versus retina. These results may suggest that reduction of NF-κB pathway activation and reduction of inflammation by progesterone after injury are at least partially mediated by PR. However, progesterone also inhibits inflammation via its actions at the glucocorticoid receptor, so multiple mechanisms could be involved (Lei et al., 2012).

While progesterone treatment effects are not as great in the retina as the brain, our results suggest that progesterone treatment may be useful clinically in treating the retinal deficits that accompany stroke, as well as the stroke itself. Progesterone may also prove to be a useful treatment for retinal ischemia and other retinal diseases, though treatment may need to be adjusted in the retina to account for progesterone receptor differences.

Acknowledgments

H. Allen and Company, Atlanta VA Rehab R&D Center of Excellence, Laney Graduate School of Emory University, Foundation Fighting Blindness, unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, NIH National Eye Institute, P30EY006360, and T32EY007092-24. We thank Heather Cale, Irina Lucaciu, Max Farina, Connie Zhang, and Anna Bausum for their help with surgeries and western blots, and Leslie McCann for her help with editing and manuscript preparation.

References

- Akiyama K, Nakanishi S, Nakamura NH, Naito T. Gene expression profiling of neuropeptides in mouse cerebellum, hippocampus, and retina. Nutrition. 2008;24(9):918–923. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Olsen TW, Sayeed I, Cale HA, Morrison KC, Oumarbaeva Y, Stein DG. Progesterone treatment in two rat models of ocular ischemia. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2015;56(5):2880–2891. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Sayeed I, Cale HA, Morrison KC, Boatright JH, Pardue MT, Stein DG. Severity of middle cerebral artery occlusion determines retinal deficits in rats. Experimental Neurology. 2014;254:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Stein DG. Progesterone as a potential neuroprotective treatment in the retina. Expert Review of Ophthalmology. 2014;9(5):375–385. doi: 10.1586/17469899.2014.949673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagowski CP, Myers JW, Ferrell JE., Jr The classical progesterone receptor associates with p42 MAPK and is involved in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(40):37708–37714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Hartz AM, Fricker G, Miller DS. Pregnane × receptor up-regulation of P-glycoprotein expression and transport function at the blood-brain barrier. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;66(3):413–419. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.3.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavente O, Eliasziw M, Streifler JY, Fox AJ, Barnett HJ, Meldrum H North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial, C. Prognosis after transient monocular blindness associated with carotid-artery stenosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(15):1084–1090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti R, Williams AJ, Moffett JR, Hale SL, Velarde LC, Elliott PJ, Tortella FC. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of inflammatory gene expression associated with ischemia-reperfusion brain injury. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2002;22(9):1068–1079. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block F, Grommes C, Kosinski C, Schmidt W, Schwarz M. Retinal ischemia induced by the intraluminal suture method in rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;232(1):45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonyaratanakornkit V, Bi Y, Rudd M, Edwards DP. The role and mechanism of progesterone receptor activation of extra-nuclear signaling pathways in regulating gene transcription and cell cycle progression. Steroids. 2008;73(9–10):922–928. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock R. Hypothermia and open cardiotomy. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1956;49(6):347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Arroyo I, Perez-Palacios G, Pasapera AM, Cerbon MA. Intracellular progesterone receptors are differentially regulated by sex steroid hormones in the hypothalamus and the cerebral cortex of the rabbit. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1994;50(5–6):299–303. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascio C, Russo D, Drago G, Galizzi G, Passantino R, Guarneri R, Guarneri P. 17beta-estradiol synthesis in the adult male rat retina. Experimental Eye Research. 2007;85(1):166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cekic M, Cutler SM, VanLandingham JW, Stein DG. Vitamin D deficiency reduces the benefits of progesterone treatment after brain injury in aged rats. Neurobiology of Aging. 2011;32(5):864–874. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Wang JM, Irwin RW, Yao J, Liu L, Brinton RD. Allopregnanolone promotes regeneration and reduces beta-amyloid burden in a preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e24293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherradi N, Chambaz EM, Defaye G. Organization of 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase and cytochrome P450scc into a catalytically active molecular complex in bovine adrenocortical mitochondria. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1995;55(5–6):507–514. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coca-Prados M, Ghosh S, Wang Y, Escribano J, Herrala A, Vihko P. Sex steroid hormone metabolism takes place in human ocular cells. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2003;86(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SM, Cekic M, Miller DM, Wali B, VanLandingham JW, Stein DG. Progesterone improves acute recovery after traumatic brain injury in the aged rat. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2007;24(9):1475–1486. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang J, Mitkari B, Kipp M, Beyer C. Gonadal steroids prevent cell damage and stimulate behavioral recovery after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in male and female rats. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2011;25(4):715–726. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nicola AF, Gonzalez-Deniselle MC, Garay L, Meyer M, Gargiulo-Monachelli G, Guennoun R, Poderoso JJ. Progesterone protective effects in neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jne.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, Kaplan B, Jacewicz M, Pulsinelli W. Continuous measurement of cerebral cortical blood flow by laser-Doppler flowmetry in a rat stroke model. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 1989;9(5):589–596. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan F, O’Driscoll C, Kenna P, Cotter TG. Enhancing survival of photoreceptor cells in vivo using the synthetic progestin Norgestrel. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2011;118(5):915–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew PD, Chavis JA. Female sex steroids: Effects upon microglial cell activation. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2000;111(1–2):77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvoriantchikova G, Barakat D, Brambilla R, Agudelo C, Hernandez E, Bethea JR, Ivanov D. Inactivation of astroglial NF-kappa B promotes survival of retinal neurons following ischemic injury. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;30(2):175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman I, Breier A. Effects of acute metabolic stress on plasma progesterone and testosterone in male subjects: Relationship to pituitary-adrenocortical axis activation. Life Sciences. 1997;61(17):1705–1712. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00776-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre EJ, Daniel AR, Hillard CJ, Lange CA. Progesterone receptor rapid signaling mediates serine 345 phosphorylation and tethering to specificity protein 1 transcription factors. Molecular Endocrinology. 2008;22(4):823–837. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre EJ, Lange CA. Progesterone receptors upregulate Wnt-1 to induce epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and c-Src-dependent sustained activation of Erk1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase in breast cancer cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2007;27(2):466–480. doi: 10.1128/mcb.01539-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falke P, Abela BM, Jr, Krakau CE, Lilja B, Lindgarde F, Maly P, Stavenow L. High frequency of asymptomatic visual field defects in subjects with transient ischaemic attacks or minor strokes. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1991;229(6):521–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoumari AM, Baulieu EE, Schumacher M. Progesterone increases oligodendroglial cell proliferation in rat cerebellar slice cultures. Neuroscience. 2005;135(1):47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoumari AM, Ibanez C, El-Etr M, Leclerc P, Eychenne B, O’Malley BW, Schumacher M. Progesterone and its metabolites increase myelin basic protein expression in organotypic slice cultures of rat cerebellum. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;86(4):848–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CL, Constantin D, Prior MJ, Bath PM, Murphy SP. Progesterone suppresses the inflammatory response and nitric oxide synthase-2 expression following cerebral ischemia. Experimental Neurology. 2005;193(2):522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Deniselle MC, Garay L, Gonzalez S, Guennoun R, Schumacher M, De Nicola AF. Progesterone restores retrograde labeling of cervical motoneurons in Wobbler mouse motoneuron disease. Experimental Neurology. 2005;195(2):518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarneri P, Guarneri R, Cascio C, Pavasant P, Piccoli F, Papadopoulos V. Neurosteroidogenesis in rat retinas. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;63(1):86–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63010086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guennoun R, Meffre D, Labombarda F, Gonzalez SL, Deniselle MC, Stein DG, Schumacher M. The membrane-associated progesterone-binding protein 25-Dx: Expression, cellular localization and up-regulation after brain and spinal cord injuries. Brain Research Reviews. 2008;57(2):493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Araiza C, Coyoy-Salgado A, Camacho-Arroyo I. Sex differences in the regulation of progesterone receptor isoforms expression in the rat brain. Brain Research Bulletin. 2002;59(2):105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00845-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Araiza C, Villamar-Cruz O, Gonzalez-Arenas A, Chavira R, Camacho-Arroyo I. Changes in progesterone receptor isoforms content in the rat brain during the oestrous cycle and after oestradiol and progesterone treatments. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2003;15(10):984–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangai M, Yoshimura N, Honda Y. Increased cytokine gene expression in rat retina following transient ischemia. Ophthalmic Research. 1996;28(4):248–254. doi: 10.1159/000267910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AM, Miller DS, Bauer B. Restoring blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein reduces brain amyloid-beta in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular Pharmacology. 2010;77(5):715–723. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayreh SS. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Arch Neurol. 1981;38(11):675–678. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1981.00510110035002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayreh SS, Weingeist TA. Experimental occlusion of the central artery of the retina. IV: Retinal tolerance time to acute ischaemia. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1980;64(11):818–825. doi: 10.1136/bjo.64.11.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius J, Arsava EM, Goldstein JN, Cestari DM, Buonanno FS, Rosen BR, Ay H. Concurrent acute brain infarcts in patients with monocular visual loss. Annals of Neurology. 2012;72(2):286–293. doi: 10.1002/ana.23597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JK, Gunion-Rinker L, Kulhanek D, Lessov N, Kim S, Clark WM, Eckenstein FP. Temporal modulation of cytokine expression following focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Brain Research. 1999;820(1–2):45–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard RB, Sayeed I, Stein D. Suboptimal dosing parameters as possible factors in the negative Phase III clinical trials of progesterone in TBI. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2015 doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4179. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua F, Wang J, Sayeed I, Ishrat T, Atif F, Stein DG. The TRIF-dependent signaling pathway is not required for acute cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;390(3):678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain R, El-Etr M, Gaci O, Rakotomamonjy J, Macklin WB, Kumar N, Ghoumari AM. Progesterone and Nestorone facilitate axon remyelination: A role for progesterone receptors. Endocrinology. 2011;152(10):3820–3831. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka F, Shimazawa M, Umigai N, Ogishima H, Nakamura S, Tsuruma K, Hara H. Crocetin, a carotenoid derivative, inhibits retinal ischemic damage in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;703(1–3):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishrat T, Sayeed I, Atif F, Hua F, Stein DG. Progesterone and allopregnanolone attenuate blood-brain barrier dysfunction following permanent focal ischemia by regulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinases. Experimental Neurology. 2010;226(1):183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishrat T, Sayeed I, Atif F, Stein DG. Effects of progesterone administration on infarct volume and functional deficits following permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Research. 2009;1257:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang SY, Zou YY, Wang JT. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-induced nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cell activity is required for neuroprotection in retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Molecular Vision. 2012;18:2096–2106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Testas I, Schumacher M, Robel P, Baulieu EE. Demonstration of progesterone receptors in rat Schwann cells. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1996;58(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(96)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat HDC, Baher AB. Recovery of function following arrest of the brain circulation. American Journal of Physiology. 1941;112:737–747. [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, Lehmann JM. An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell. 1998;92(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulen P, Madry C, Duncan RS, Hwang JY, Nixon E, McClung N, Singh M. Progesterone potentiates IP(3)-mediated calcium signaling through Akt/PKB. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2008;21(1–3):161–172. doi: 10.1159/000113758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labombarda F, Ghoumari AM, Liere P, De Nicola AF, Schumacher M, Guennoun R. Neuroprotection by steroids after neurotrauma in organotypic spinal cord cultures: A key role for progesterone receptors and steroidal modulators of GABAA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2013;71:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labombarda F, Gonzalez SL, Deniselle MC, Vinson GP, Schumacher M, De Nicola AF, Guennoun R. Effects of injury and progesterone treatment on progesterone receptor and progesterone binding protein 25-Dx expression in the rat spinal cord. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;87(4):902–913. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmade SJ, Gale SE, Frolov A, Mohri I, Suzuki K, Mellon SH, Ory DS. Pregnane × receptor (PXR) activation: A mechanism for neuroprotection in a mouse model of Niemann-Pick C disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(37):13807–13812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606218103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanthier A, Patwardhan VV. Sex steroids and 5-en-3 beta-hydroxysteroids in specific regions of the human brain and cranial nerves. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 1986;25(3):445–449. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(86)90259-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanthier A, Patwardhan VV. Effect of heterosexual olfactory and visual stimulation on 5-en-3 beta-hydroxysteroids and progesterone in the male rat brain. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 1987;28(6):697–701. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(87)90400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanthier A, Patwardhan VV. In vitro steroid metabolism by rat retina. Brain Research. 1988;463(2):403–406. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei K, Chen L, Georgiou EX, Sooranna SR, Khanjani S, Brosens JJ, Johnson MR. Progesterone acts via the nuclear glucocorticoid receptor to suppress IL-1beta-induced COX-2 expression in human term myometrial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Hayes S, Young AP. Steroid hormone receptors activate transcription in glial cells of intact retina but not in primary cultures of retinal glial cells. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 1997;8(2):145–158. doi: 10.1007/bf02736779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Margaill I, Zhang S, Labombarda F, Coqueran B, Delespierre B, Guennoun R. Progesterone receptors: A key for neuroprotection in experimental stroke. Endocrinology. 2012;153(8):3747–3757. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20(1):84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N, Li C, Cheng Y, Du AL. Protective effects of progesterone against high intraocular pressure-induced retinal ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;28(11):2026–2029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller JL. The elusive progesterone receptor in Xenopus oocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2001;98(1):8–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice T, Su TP, Privat A. Sigma1 (sigma 1) receptor agonists and neurosteroids attenuate B25-35-amyloid peptide-induced amnesia in mice through a common mechanism. Neuroscience. 1998;83(2):413–428. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis JF, Leveille PJ. A biomolecular approach to the study of the expression of speicific genes in the retina. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 16(1):157–165. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490160115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead GE, Lewis SC, Wardlaw JM, Dennis MS. Comparison of risk factors in patients with transient and prolonged eye and brain ischemic syndromes. Stroke. 2002;33(10):2383–2390. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000029827.93497.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meffre D, Pianos A, Liere P, Eychenne B, Cambourg A, Schumacher M, Guennoun R. Steroid profiling in brain and plasma of male and pseudopregnant female rats after traumatic brain injury: Analysis by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Endocrinology. 2007;148(5):2505–2517. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A. Neuropathological aspects of anoxia. Proc R Soc Med. 1956;49(9):619–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Hunt JS. Regulation of TNF-alpha production in activated mouse macrophages by progesterone. Journal of Immunology. 1998;160(10):5098–5104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann F, Wurm A, Linnertz R, Pannicke T, Iandiev I, Wiedemann P, Bringmann A. Sex steroids inhibit osmotic swelling of retinal glial cells. Neurochemical Research. 2010;35(4):522–530. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliser HK, Yates DM, Hirst JJ. Progesterone receptor isoform expression in response to in utero growth restriction in the fetal guinea pig brain. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;96(1):60–67. doi: 10.1159/000335138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons B, Rainbow TC, MacLusky NJ, McEwen BS. Progestin receptor levels in rat hypothalamic and limbic nuclei. Journal of Neuroscience. 1982;2(10):1446–1452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-10-01446.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G, Belelli D. Neurosteroids on our minds. Trends in Pharmacological Science. 2001;22(6):266–267. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, O’Malley BW, Rogawski MA. Anxiolytic activity of progesterone in progesterone receptor knockout mice. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48(1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumelt S, Dorenboim Y, Rehany U. Aggressive systematic treatment for central retinal artery occlusion. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1999;128(6):733–738. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H, Ukena K, Tsutsui K. Effects of progesterone synthesized de novo in the developing Purkinje cell on its dendritic growth and synaptogenesis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(16):6221–6232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06221.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vallejo V, Benlloch-Navarro S, Lopez-Pedrajas R, Romero FJ, Miranda M. Neuroprotective actions of progesterone in an in vivo model of retinitis pigmentosa. Pharmacological Research. 2015;99:276–288. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed I, Stein DG. Progesterone as a neuroprotective factor in traumatic and ischemic brain injury. [Review] Progress in Brain Research. 2009;175:219–237. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallner N, Fuchs M, Schwer CI, Loop T, Buerkle H, Lagreze WA, Goebel U. Postconditioning with inhaled carbon monoxide counteracts apoptosis and neuroinflammation in the ischemic rat retina. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e46479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Martin-Villalba A, Weih F, Vogel J, Wirth T, Schwaninger M. NF-kappaB is activated and promotes cell death in focal cerebral ischemia. Nature Medicine. 1999;5(5):554–559. doi: 10.1038/8432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Stein DG, De Nicola AF. Progesterone: Therapeutic opportunities for neuroprotection and myelin repair. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2007;116(1):77–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Mattern C, Ghoumari A, Oudinet JP, Liere P, Labombarda F, Guennoun R. Revisiting the roles of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the nervous system: Resurgence of the progesterone receptors. Progress in Neurobiology. 2014;113:6–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick BE, Maas AI, Narayan RK, van der Hoop RG, MacAllister T, Ward JD The, S.T.I. A clinical trial of progesterone for severe Traumatic Brain Injury. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(26):2467–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepyan DH, Rankin RM, Stahler C, Jr, Gibbons GE. Amaurosis fugax: A clinical comparison. Stroke. 1975;6(5):493–496. doi: 10.1161/01.str.6.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souidi M, Gueguen Y, Linard C, Dudoignon N, Grison S, Baudelin C, Dublineau I. In vivo effects of chronic contamination with depleted uranium on CYP3A and associated nuclear receptors PXR and CAR in the rat. Toxicology. 2005;214(1–2):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele EC, Jr, Guo Q, Namura S. Filamentous middle cerebral artery occlusion causes ischemic damage to the retina in mice. Stroke. 2008;39(7):2099–2104. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.107.504357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DG. Embracing failure: What the Phase III progesterone studies can teach about TBI clinical trials. Brain Injury. 2015;29(11):1259–1272. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2015.1065344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DG, Wright DW. Progesterone in the clinical treatment of acute traumatic brain injury. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2010;19(7):847–857. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.489549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D, Yin T, Smalstig EB, Hsu MA, Panetta J, Little S, Clemens J. Transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B is activated in neurons after focal cerebral ischemia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2000;20(3):592–603. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey J. The positive false discovery rate: A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Annals of Statistics. 2003;31:2013–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Stowell C, Wang L, Arbogast B, Lan JQ, Cioffi GA, Burgoyne CF, Zhou A. Retinal proteomic changes under different ischemic conditions - implication of an epigenetic regulatory mechanism. International Journal of Physiology, Pathophysiology and Pharmacology. 2010;2(2):148–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svec F, Teubner V, Tate D. Location of the second steroid-binding site on the glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology. 1989;125(6):3103–3108. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-6-3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svec F, Yeakley J, Harrison RW., 3rd Progesterone enhances glucocorticoid dissociation from the AtT-20 cell glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology. 1980;107(2):566–572. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-2-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swales KE, Moore R, Truss NJ, Tucker A, Warner TD, Negishi M, Bishop-Bailey D. Pregnane × receptor regulates drug metabolism and transport in the vasculature and protects from oxidative stress. Cardiovascular Research. 2012;93(4):674–681. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiatek-De Lange M, Stampfl A, Hauck SM, Zischka H, Gloeckner CJ, Deeg CA, Ueffing M. Membrane-initiated effects of progesterone on calcium dependent signaling and activation of VEGF gene expression in retinal glial cells. Glia. 2007;55(10):1061–1073. doi: 10.1002/glia.20523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Hua F, Wang J, Yousuf S, Atif F, Sayeed I, Stein DG. Progesterone and vitamin D combination therapy modulates inflammatory response after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2015.1035330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui K. Biosynthesis and organizing action of neurosteroids in the developing Purkinje cell. Cerebellum. 2006;5(2):89–96. doi: 10.1080/14734220600697211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui K, Ukena K, Usui M, Sakamoto H, Takase M. Novel brain function: Biosynthesis and actions of neurosteroids in neurons. Neuroscience Research. 2000;36(4):261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu XK, Yang WZ, Shi SS, Wang CH, Zhang GL, Ni TR, Song QM. Spatio-temporal distribution of inflammatory reaction and expression of TLR2/4 signaling pathway in rat brain following permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Neurochemical Research. 2010;35(8):1147–1155. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valera S, Ballivet M, Bertrand D. Progesterone modulates a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 1992;89(20):9949–9953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AK, McCullough EH, Niyonkuru C, Ozawa H, Loucks TL, Dobos JA, Fabio A. Acute serum hormone levels: Characterization and prognosis after severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2011;28(6):871–888. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wali B, Ishrat T, Won S, Stein DG, Sayeed I. Progesterone in experimental permanent stroke: A dose-response and therapeutic time-window study. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 2):486–502. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jiang S, Kwong JM, Sanchez RN, Sadun AA, Lam TT. Nuclear factor-kappaB p65 and upregulation of interleukin-6 in retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Brain Research. 2006;1081(1):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters EM, Torres-Reveron A, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Ultrastructural localization of extranuclear progestin receptors in the rat hippocampal formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008;511(1):34–46. doi: 10.1002/cne.21826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger LGM, Gibbon JH. Temporary arrest of the circulation to the central nervous system: I. Physiologic effects. II. Pathologic effects. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 1940;43:615–634. 961–686. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham LA, Gao J, Toda I, Rocha EM, Ono M, Sullivan DA. Identification of androgen, estrogen and progesterone receptor mRNAs in the eye. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2000;78(2):146–153. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078002146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won S, Lee JH, Wali B, Stein DG, Sayeed I. Progesterone attenuates hemorrhagic transformation after delayed tPA treatment in an experimental model of stroke in rats: Involvement of the VEGF-MMP pathway. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2014;34(1):72–80. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DW, Kellermann AL, Hertzberg VS, Clark PL, Frankel M, Goldstein FC, Stein DG. ProTECT: A randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007;49(4):391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DW, Yeatts SD, Silbergleit R, Palesch YY, Hertzberg VS, Frankel M, Investigators N. Very early administration of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(26):2457–2466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyse Jackson AC, Roche SL, Byrne AM, Ruiz-Lopez AM, Cotter TG. Progesterone receptor signalling in retinal photoreceptor neuroprotection. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2016;136(1):63–77. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Wei J, Yan W, Wang W, Lu Z. Improved outcomes from the administration of progesterone for patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Critical Care. 2008;12(2):R61. doi: 10.1186/cc6887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf S, Atif F, Sayeed I, Wang J, Stein DG. Post-stroke infections exacerbate ischemic brain injury in middle-aged rats: Immunomodulation and neuroprotection by progesterone. Neuroscience. 2013;239:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li C, Sun X, Kuang X, Ruan X. High glucose decreases expression and activity of p-glycoprotein in cultured human retinal pigment epithelium possibly through iNOS induction. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lu M, Sun X, Li C, Kuang X, Ruan X. Expression and activity of p-glycoprotein elevated by dexamethasone in cultured retinal pigment epithelium involve glucocorticoid receptor and pregnane × receptor. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2012;53(7):3508–3515. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitzmann M, Erren M, Kamischke A, Simoni M, Nieschlag E. Endogenous progesterone and the exogenous progestin norethisterone enanthate are associated with a proinflammatory profile in healthy men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;90(12):6603–6608. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchini N, de Sousa G, Bailly-Maitre B, Gugenheim J, Bars R, Lemaire G, Rahmani R. Regulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL anti-apoptotic protein expression by nuclear receptor PXR in primary cultures of human and rat hepatocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2005;1745(1):48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]