Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the effect of early frailty transitions on 15-year mortality risk.

Methods

Longitudinal data analysis of the Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiological Study of the Elderly involving 1,171 community-dwelling Mexican Americans aged ≥ 67 years and older. Frailty was determined using the modified Frailty Phenotype, including unintentional weight loss, weakness, self-reported exhaustion and slow walking speed. Participants were defined at baseline as non-frail, pre-frail or frail and divided into nine transition groups, during a three-year observation period.

Results

Mean age was 77.0 (SD=5.3) and 59.1% were female. Participants who transitioned from pre-frail to frail [Hazard Ratio (HR) =1.68, 95%CI=1.23-2.28], frail to pre-frail [HR=1.54, 95%CI=1.05-2.28]; or who remained frail [HR=1.72, 95%CI=1.21-2.44], had significant higher 15-year mortality risk than those who remained non-frail. Participants transitioning from frail to non-frail had a similar15-year mortality risk as those who remained non-frail (HR=0.96, 95%CI [0.53, 1.72]). Weight loss and slow walking speed were associated with transitions to frailty.

Conclusions

An early transition from frail to non-frail in older Mexican Americans was associated with a 4% decrease in mortality compared to those who remained non-frail, although this difference was not statistically significant. Additional longitudinal research is needed to understand positive transitions in frailty.

Keywords: Frail Elderly, Mortality, Mexican Americans

INTRODUCTION

Frailty is a common geriatric syndrome, widely associated with adverse health outcomes including falls, disability, cognitive decline, hospitalization, increased health services utilization, and mortality1-6. Approximately, 50% of adults in the U.S. aged 65 years and older are frail7. Among community-dwelling older adults, 10-25% of those over 65 and 46% over age 80 are frail8.

In disadvantaged and ethnic minorities, frailty prevalence is higher9. Research suggests that minority and disadvantaged populations could be affected more by frailty because of less access to educational and healthcare resources and economic disadvantage compared to non-Hispanic Whites10. Hispanic older adults also have a significantly higher incidence of certain medical conditions, such as diabetes and obesity, than non-Hispanic White11. Hispanics are currently the largest U.S. minority population; comprising 17.6% of the total population, with 3.1 million aged 65 and older12. From 2000 to 2020, this Hispanic older population will grow by 76%, compared to 38% for non-Hispanic Whites and 34% for African Americans13.

While our knowledge of frailty and disability has improved dramatically in the past decade, little is known about frailty transition in the older minority population. Mexican Americans’ access to, and use of, health care services is different from that of non-Hispanic Whites14. For example, when the Affordable Care Act was implemented, over 40% of Mexican Americans were without health insurance14, the highest rate of any racial or ethnic group in the U.S. Research is needed to better understand frailty transition in older Mexican Americans to determine effective methods for prevention and intervention. This information is particularly important for persons 80 years and older who will experience higher levels of frailty and subsequent disability6. Health care costs are also the highest for this age category15, as 5% of Medicare beneficiaries are responsible for ~50% of Medicare spending16. A large portion of these 5% includes persons >80 years with frailty and chronic conditions16. To improve health care and reduce costs, a better understanding of this minority and disadvantaged sub-population of persons >80 years is essential.

More longitudinal studies of frailty are also needed in the oldest segment of the Mexican American population (> 80 years). Previous longitudinal research17-19 has examined frailty transitions in non-Hispanic older adults using the states of non-frail, pre-frail and frail20 and also the cumulative number of deficits as identified by the Frailty Index (FI)21. Gill et al.17 suggest that transitions occur most frequently between adjacent states of frailty and these states interact in complex ways that influence functional status, disability, hospitalizations, and mortality. Fallah et al.18 found that baseline frailty status, age and mobility were significantly associated with frailty transition. Pollack et al.19 found that frailty status could be improved by managing comorbidity, disability, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) function, physical exercise, nutritional and social support. However, frailty may manifest in different ways within racial and ethnic groups; and whether findings from non-Hispanic Whites can be applied to Hispanic older adults remains unclear.

This study examined changes in frailty states over three years and monitored mortality for the next 15 years in a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling older Mexican Americans. We hypothesized that different early frailty transition patterns would be associated with different long-term mortality risk.

METHODS

Data Source

Data were retrieved from the Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiological Study of the Elderly (EPESE), an ongoing, longitudinal study of community-dwelling Mexican Americans aged 65 years or older since 1993/94. The Hispanic EPESE used geographical probability sampling procedures to select participants from five Southwestern states: Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and California. Nine waves of data have been collected from 1993 to 2016. The current study used data obtained from the 2nd to the 8th Wave (1995/96–2012/13). A detailed description of EPESE is available elsewhere.11

Cohort Selection Criteria

This study included participants who did not report any functional disability at baseline (Wave 2, 1995/96). Functional disability was determined if the participant required assistance or was not able to perform one of the following items from the Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale22: walking, bathing, grooming, dressing, eating, transferring-bed to chair and toileting.

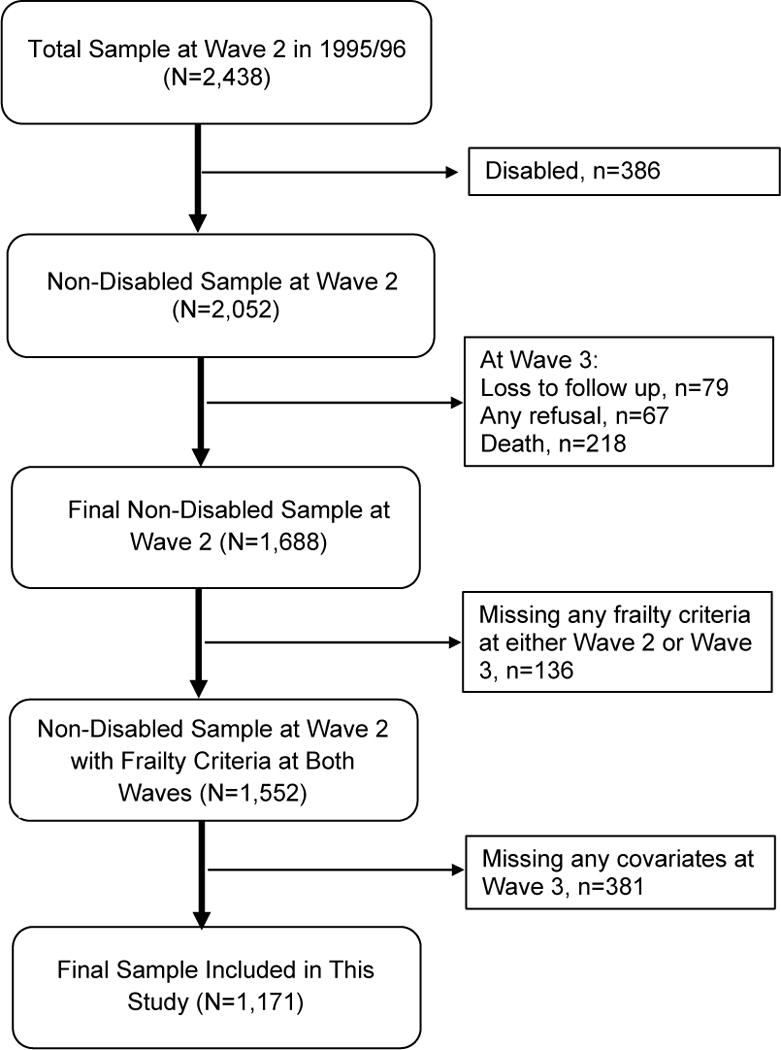

A total of 364 participants were lost-to-follow-up from Wave 2 to 3. We also exclude 136 participants with missing information on the frailty items at either Wave 2 or 3, and 381 participants with missing information in any covariates at Wave 3. The final sample included 1,171 participants. Appendix Figure 1 demonstrates the cohort selection process for the study.

Modified Frailty Phenotype

Frailty was assessed based on a modified measure described by Fried et al.20 and referred to as the modified Frailty Phenotype, because physical activity data were not available in all eight Waves of the Hispanic EPESE data collection. The physical activity data were only collected at Wave 2 due to a different research focus of the Hispanic EPESE project over time. Four frailty items were used: weight loss, weakness, exhaustion and slow walking. Participants with unintentional weight loss of >4.5 kilograms were categorized as positive for the weight loss criterion (score = 1). Exhaustion was identified using two items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale23: “I felt everything I did was an effort” and “I could not get going.” The respondents answered, “How often in the last week did you feel this way?” 0= rarely or none of the time (<1 day), 1= some or a little of the time (1–2 days), 2= a moderate amount of the time (3–4 days), or 3= most of the time (5–7 days). Participants answering “2” or “3” to either of these two items were scored as positive (score=1). Walking speed was assessed with a 2.4-meter timed walk test at normal pace. The test time was adjusted for height and gender and the slowest 20% were scored as positive (score = 1). Persons unable to perform the walk were also scored 1. Grip strength (weakness) was assessed using a handheld dynamometera. Participants unable to perform the handgrip test and those in the lowest 20% [adjusted for BMI (Body Mass Index: calculated by weight {kg}/height2 {meters}) and gender] were categorized as positive for weakness (score = 1). The summary frailty score ranged from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating increased frailty. Participants were categorized as non-frail (0 criterion), pre-frail (1 criterion) and frail (2+ criterion).

Early Frailty Transitions

Early frailty transitions was defined as the absolute change in frailty state measured at two earliest time points, 1995/96 (Wave 2) and 1998/99 (Wave 3), for our study cohort. Participants were stratified into nine transition groups: 1) non-frail to non-frail, 2) non-frail to pre-frail, 3) non-frail to frail, 4) pre-frail to non-frail, 5) pre-frail to pre-frail, 6) pre-frail to frail, 7) frail to non-frail, 8) frail to pre-frail, and 9) frail to frail (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics among Non-disabled Mexican Americans.

| Total | Total | Nine Frailty Transition Group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Variables |

All Wave2 (N=2438)* |

All Wave3 (N=1171)& |

Remained NonFrail (N=357) |

Non-Pre (N=222) |

Non-Frail (N=98) |

Pre-Non (N=164) |

Remained Prefrail (N=140) |

Pre-Frail (N=74) |

Frail-Non (N=27) |

Frail-Pre (N=41) |

Remained Frail (N=48) |

| Age, Number (%)# | |||||||||||

| 65-74 years | 1274(52.3) | 446(39.8) | 164(45.9) | 95(42.8) | 29(29.6) | 63(38.4) | 51(36.4) | 27(36.5) | 16(59.3) | 12(29.3) | 9(18.8) |

| 75-84 years | 879(36.1) | 587(50.1) | 173(48.5) | 104(46.9) | 58(59.2) | 86(52.4) | 74(52.9) | 33(44.6) | 9(33.3) | 21(51.2) | 29(60.4) |

| 85+ years | 285(11.7) | 118(10.1) | 20(5.6) | 23(10.4) | 11(11.2) | 15(9.2) | 15(10.7) | 14(18.9) | 2(7.4) | 8(19.5) | 10(20.8) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Age, Mean (SD) # | 75.6(6.6) | 77.0 (5.3) | 75.9(4.4) | 76.8(5.5) | 78.0(5.0) | 77.0(5.1) | 76.9(5.1) | 78.7(6.7) | 75.2(5.3) | 79.2(6.1) | 80.1(6.3) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 1014(41.6) | 480 (40.9) | 155(43.4) | 71(32.0) | 36(36.7) | 75(45.7) | 63(45.0) | 34(46.0) | 12(44.4) | 16(39.0) | 18(37.5) |

| Female | 1424(58.4) | 691 (59.1) | 202(56.6) | 151(68.0) | 62(63.3) | 89(54.3) | 77(55.0) | 40(54.1) | 15(55.6) | 25(61.0) | 30(62.5) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Education (years) # | |||||||||||

| 0 | 426(17.7) | 166 (14.2) | 53(14.8) | 26(11.7) | 18(18.4) | 18(11.0) | 22(15.7) | 16(21.6) | 1(3.7) | 3(7.3) | 9(18.8) |

| 1-7 | 1436(59.8) | 726 (62.0) | 203(56.9) | 125(56.3) | 68(69.4) | 107(65.2) | 87(62.1) | 51(68.9) | 21(77.8) | 30(73.2) | 34(70.8) |

| 8-11 | 308(12.8) | 154 (13.2) | 52(14.6) | 38(17.1) | 7(7.1) | 19(11.6) | 22(15.7) | 4(5.4) | 3(11.1) | 7(17.1) | 2(4.2) |

| 12+ | 232(9.7) | 125 (10.7) | 49(13.7) | 33(14.9) | 51(5.1) | 20(12.2) | 9(6.4) | 3(4.1) | 2(7.4) | 1(2.4) | 3(6.2) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Marital Status | |||||||||||

| Married | 1294(53.1) | 620(52.9) | 200(56.0) | 112(50.5) | 43(43.9) | 90(54.9) | 73(52.1) | 40(54.0) | 19(70.4) | 21(51.2) | 22(45.8) |

| Unmarried | 1144(46.9) | 551(47.1) | 157(44.0) | 110(49.5) | 55(56.1) | 74(45.1) | 67(47.9) | 34(46.0) | 8(29.6) | 20(48.8) | 26(54.2) |

|

| |||||||||||

| BMI Group# | |||||||||||

| <18.5 | 13(1.1) | 19(1.6) | 1(0.3) | 2(0.9) | 3(3.1) | 2(1.2) | 7(50) | 2(2.7) | 0(0.0) | 1(2.4) | 1(2.1) |

| 18.5-<25 | 294(25.1) | 301(25.7) | 83(23.3) | 65(29.3) | 33(33.7) | 44(26.8) | 25(17.9) | 19(25.7) | 4(14.8) | 10(24.4) | 18(37.5) |

| 25-<30 | 469(40.0) | 457(39.0) | 140(39.2) | 82(36.9) | 33(33.7) | 73(44.5) | 62(44.3) | 26(35.1) | 11(40.7) | 17(41.5) | 13(27.1) |

| ≥30 | 397(33.8) | 394(33.7) | 133(37.2) | 73(32.9) | 29(30.0) | 45(27.4) | 46(32.9) | 27(36.5) | 12(44.5) | 13(31.7) | 16(33.3) |

|

| |||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2), Mean (SD) | 27.9(5.3) | 28.3(5.2) | 28.6(4.7) | 28.3(5.6) | 27.6(6.1) | 27.7(4.5) | 28.5(5.5) | 28.2(5.7) | 29.4(3.9) | 27.6(5.1) | 28.2(6.1) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Cognitive Impairment # (MMSE<21), N(%) | 584(25.9) | 361(30.8) | 92(25.8) | 52(23.4) | 42(42.9) | 44(26.8) | 47(33.6) | 37(50.0) | 9(33.3) | 15(36.6) | 23(47.9) |

|

| |||||||||||

| ADL Disabledˆ# | 386(15.8) | 91(7.8) | 11(3.1) | 10(4.5) | 19(19.4) | 3(1.8) | 11(7.9) | 18(24.3) | 0(0.0) | 3(7.3) | 16(33.3) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Smoking, N(%) | 278(11.4) | 121(10.3) | 36(10.1) | 26(11.7) | 9(9.2) | 17(10.4) | 18(12.9) | 6(8.1) | 3(11.1) | 0(0.0) | 6(12.5) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Comorbidity | |||||||||||

| Diabetes | 669(27.5) | 317(27.0) | 91(25.5) | 63(28.4) | 26(26.5) | 29(17.7) | 49(35.0) | 25(33.8) | 7(25.9) | 12(29.3) | 15(31.3) |

| Hypertension | 1392(57.1) | 710(60.6) | 212(59.1) | 142(63.9) | 57(58.2) | 92(56.1) | 82(58.6) | 50(67.6) | 18(66.7) | 29(70.7) | 29(60.4) |

| Heart attack# | 235(9.7) | 72(6.2) | 22(6.2) | 8(3.6) | 7(7.1) | 5(3.1) | 8(5.7) | 16(21.6) | 0(0.0) | 4(9.8) | 2(4.2) |

| Stroke | 243(10.0) | 43(3.7) | 10(2.8) | 10(4.5) | 3(3.1) | 4(2.4) | 6(4.3) | 7(9.5) | 0(0.0) | 1(2.4) | 2(4.2) |

| Cancer# | 147(7.2) | 62(5.3) | 15(4.2) | 8(3.6) | 8(8.2) | 4(6.5) | 15(10.7) | 5(6.8) | 0(0.0) | 3(7.3) | 4(8.3) |

| Fracture | 44(1.8) | 13(1.1) | 1(0.3) | 3(1.4) | 1(1.0) | 3(1.8) | 1(0.7) | 2(2.7) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 2(4.2) |

| Arthritis | 1091(44.9) | 517(48.8) | 165(46.2) | 103(46.4) | 55(56.1) | 73(44.5) | 73(52.1) | 40(54.1) | 12(44.4) | 21(51.2) | 29(60.4) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Comorbidity, Mean (SD) # | 1.58(1.1) | 1.5(1.0) | 1.4(1.0) | 1.5(1.0) | 1.6(1.0) | 1.3(0.9) | 1.7(1.1) | 2.0(1.2) | 1.4(0.8) | 1.7(1.0) | 1.7(1.2) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Died from 1995-2013# | 1132(67.1) | 746(63.7) | 202(56.6) | 146(65.8) | 69(70.4) | 100(61.0) | 90(64.3) | 56(75.7) | 12(44.4) | 30(73.2) | 41(85.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI (Body Mass Index), MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination), ADL (Activity of Daily Living), SD (Standard Deviation).

Wave 2 (1995/96)

Wave 3 (1998/99)

ADL Disabled was defined as help needed or unable to perform ≥1 of the seven ADL activities from Katz ADL scale (walking, bathing, grooming dressing, eating, transferring, and toileting)34.

Significant at p-value of < 0.05 among nine frailty transition groups

Functional Disability

Functional disability was assessed by items from the Katz ADL scale22 described above. ADL disability was scored as positive (yes) if the participant needed physical help or was unable to perform one or more of the seven ADL activities.

Covariates

Covariates included Wave 3 sociodemographic variables (age, gender, marital status and years of formal education), BMI, cognitive function (Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of < 21)24, smoking status and comorbidity status (self-reported presence of any of seven medical conditions: arthritis, diabetes, hypertension, heart attack, stroke, cancer or hip fracture).

Outcome

Fifteen-year mortality (1998/99-2012/13) was identified using the date of death from the National Death Index (NDI) and reports from relatives at each follow-up.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square, t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to examine the demographic distributions between the included and the excluded sample and among the nine transition groups. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the hazard of death at each follow up as a function of 2-Wave frailty transitions, controlling for socio-demographics, comorbidities, BMI, smoking status, ADL disability and cognitive impairment at Wave 3. The Cox proportional hazard regression assumption was confirmed (no proportionality issue was found). Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and nine frailty transition groups were compared using the log-rank test. Additional analyses were conducted by excluding participants who were disabled at Wave 3. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4.

Ethical Consideration

The Institutional Review Board (IRB#: 16-0014) at our institution approved this study. Participant consents were obtained verbally.

RESULTS

At baseline/Wave 2 (N=2,438), mean age was 75.6 (SD=6.6) and 58.4% were female. The mean age of the sample at Wave 3 (N=1,171) was 77.0 (SD=5.3) years. At Wave 3, the sample was 59.1% female, 52.9% married, 62.0% had 1 to 7 years of formal education, 69.2% had no cognitive impairment, 92.2% had no functional disability, 60.6% had hypertension, the sample mean BMI was 28.3 (SD=5.2), and the mean number of comorbidities was 1.5 (SD=1.0) (Table 1).

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics for the sample stratified by the nine frailty transition groups. Overall, 357 (30.5%) participants remained non-frail between Waves 2-3; 394 (33.6%) transitioned to a worse state (non-frail to pre-frail; non-frail to frail; and pre-frail to frail), 232 (19.8%) transitioned to a better state (pre-frail to non-frail; frail to non-frail; and frail to pre-frail), 140 (11.9%) remained pre-frail, and 48 (4.1%) remained frail (Table 1). Participants who transitioned to, or remained frail, were significantly more likely to be older and tended to have cognitive impairment, compared to those who remained non-frail (Table 1). Participants who remained pre-frail or frail were significantly more likely to report cancer compared with those who remained non-frail (Table 1). Those who transited from pre-frail to frail were significantly more likely to report heart attack compared to the rest (Table 1). Sensitivity analyses indicated that excluded participants were more likely to be older, unmarried, less educated, higher BMI, more comorbidities, and lower MMSE scores than the included sample (Appendix, Table 1).

Table 2 presents the hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of 15-year mortality as a function of the nine frailty transition groups, controlling for socio-demographics, smoking status, BMI, ADL disability, cognitive impairment and comorbidities. Compared to the group that remained non-frail, the HR for mortality was 1.68 (95 %CI=1.23–2.28) for those transitioning from pre-frail to frail, 1.54 (95 %CI=1.05–2.28) for those transitioning from frail to pre-frail, and 1.72 (95 %CI=1.21–2.44) for those remaining frail. Transitioning from frail to non-frail, was the only transition group with lower HR than 1.0, but not significant (HR=0.96, 95 %CI=0.53–1.72). Other factors associated with 15-year mortality were older age, less education (8-11 years), ADL disability, cognitive impairment, smoking and multiple comorbidities. Female, overweight, and obesity were associated with decreased mortality risk. Similar results were found when disabled participants at Wave 3 were excluded (Appendix, Table 2).

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazard Model of 15-Year Mortality based on Nine Early Frailty Transition Groups (1995–2013, N=1,171).

| Demographic characteristics | 15-Year Mortality HR(95%CI) |

|---|---|

| Age Group (years) | |

| 65-74 | Ref. |

| 75-84 | 1.90(1.61, 2.25)* |

| 85+ | 3.39(2.63, 4.37)* |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | Ref. |

| Female | 0.69(0.60, 0.82)* |

|

| |

| Education (years) | |

| 0 | Ref. |

| 1-7 | 1.04(0.83, 1.29) |

| 8-11 | 1.34(1.01, 1.80)* |

| 12+ | 1.24(0.91, 1.69) |

|

| |

| Marital Status | |

| Unmarried | Ref. |

| Married | 0.87(0.74, 1.02) |

|

| |

| BMI Group | |

| 18.5-<25 | Ref. |

| <18.5 | 1.56(0.93, 2.63) |

| 25-<30 | 0.82(0.68, 0.98)* |

| ≥30 | 0.74(0.61, 0.90)* |

|

| |

| Comorbidity | |

| No | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.21(1.12,1.30)* |

|

| |

| Cognitive Impairment (MMSE<21) | |

| No | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.25(1.06, 1.48)* |

|

| |

| ADL Disabledˆ | |

| No | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.47(1.14, 1.91)* |

|

| |

| Smoking | |

| No | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.63(1.30,2.04)* |

| Nine Frailty Transition& | |

| Nonfrail-nonfrail (N=357) | Ref. |

| Nonfrail-prefrail (N=222) | 1.19(0.96, 1.47) |

| Nonfrail-frail (N=98) | 1.18(0.89, 1.56) |

| Prefrail-nonfrail (N=164) | 1.05(0.83, 1.34) |

| Prefrail-prefrail (N=140) | 1.20(0.93, 1.55) |

| Prefrail-frail (N=74) | 1.68(1.23, 2.28)* |

| Frail-nonfrail (N=27) | 0.96(0.53, 1.72) |

| Frail-prefrail (N=41) | 1.54(1.05, 2.28)* |

| Frail-frail (N=48) | 1.72(1.21, 2.44)* |

95% CI is significant

In Cox regression analysis, there was no violation of the proportionality assumption assessed by the significance of a term of the predictor associated with the logarithm of survival time. The HRs were controlled for the following factors: socio-demographics, BMI, ADL disability, cognitive impairment and comorbidities

ADL Disabled was defined as help needed or unable to perform ≥1 of the seven ADL activities from Katz ADL scale (walking, bathing, grooming dressing, eating, transferring, and toileting)34.

Abbreviations: HR (Hazard Ratio), CI (Confidence Interval), BMI (Body Mass Index), MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination), ADL (Activity of Daily Living), SD (Standard Deviation).

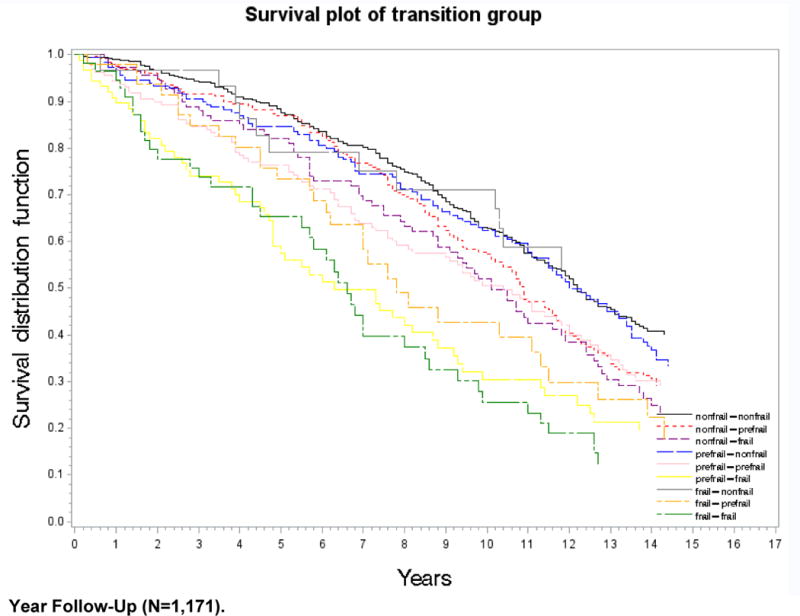

Figure 1 displays the Kaplan-Meier survival curves over 15 years following the three-year observation period as a function of the nine frailty transition groups. Those participants who remained non-frail or transitioned to non-frail (from pre-frail and frail) survived the longest, followed by those who transitioned from non-frail to pre-frail or frail, or who remained pre-frail. Those who remained frail or transitioned to frail from pre-frail or to pre-frail from frail had the shortest survival time (log-rank test, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier Survival Curve of Nine Frailty Transition Groups over 15-Year Follow-Up (N=1,171)

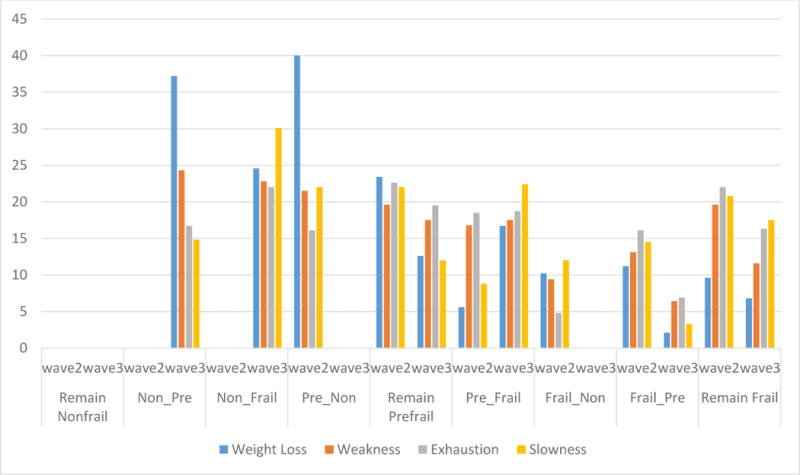

Figure 2 presents the most common frailty criteria from Wave 2 to 3 among the nine transition groups. For participants who transitioned from non-frail to pre-frail (and vice versa), the most common frailty change was weight loss (37.2%). For those who transitioned from non-frail to frail (and vice versa), the most common frailty change was slow walking (30.1%). For participants who remained pre-frail or frail, all four frailty criteria stayed similar.

Figure 2. Frailty Change (%) from Wave 2 to Wave 3 by Frailty Criteria.**.

1) Remain Non-frail: non-frail to non-frail; 2) Non_Pre: non-frail to pre-frail; 3) Non_Frail: non-frail to frail; 4) Pre_Non: pre-frail to non-frail; 5) Remain Pre-frail: pre-frail to pre-frail; 6) Pre_Frail: pre-frail to frail; 7) Frail_Non: frail to non-frail; 8) Frail_Pre: frail to pre-frail; and 9) Remain Frail: frail to frail; *Frailty was assessed based on modified items described by Fried et al. (2001).25

For those participants transitioning from pre-frail to frail, two frailty criteria increased the most: weight loss (from 5.6% to 16.7%) and slow walking (from 8.8% to 22.4%). The percent of weakness and exhaustion remained stable (16.8% to 17.5% and 18.5% to 18.7%, respectively) from Wave 2 to 3. All four frailty criteria decreased for those who transitioned from frail to pre-frail, but the largest decrease was in weight loss (from 11.2% to 2.1%) and slow walking (from 20.8% to 17.5%) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

This study examined how early transition in frailty stages over a three-year period (1995/96-1998/99) predicted 15-year mortality among non-disabled, community-dwelling older Mexican Americans. Our findings can be summarized as follows: those who remained non-frail or transitioned to non-frail survived the longest, followed by those who remained pre-frail or transitioned from non-frail to pre-frail or frail. While transitioning to the non-frail state was protective of long-term mortality, transitioning from frail to the pre-frail state was not. Participants who transitioned from pre-frail to frail, or who remained frail, showed the highest risk for mortality (~70%) over 15-year follow-up period. Our findings are the first we are aware of demonstrating that the transition from frail to non-frail is associated with decreased but not significant long-term mortality compared to those who remained non-frail in older Mexican Americans. The findings provide information to identify strategies for prevention and intervention in frailty, and further improve long-term care planning for older Mexican Americans.

Gill et al.17 found that, between baseline and an 18-month follow-up, 43% of participants progressed to a more-frail status, 34% had no change, and 23% improved. These proportions are similar to our results. In our sample, over a three-year follow-up period, 34% of participants progressed to a more-frail status, 47% had no change in status, and 20% of pre-frail or frail participants showed improved transitions. By contrast, Pollack et al.19, in a study of 5,086 community-living men 65 years and older most participants had no change in frailty status (56%), with 35% progressing in frailty status or dying, and 15% of pre-frail or frail participants improving, over 4.6 years. Our sample showed the highest relative percent of the overall sample transitioning from frail to non-frail (2.3%), compared to 0.5% - 0.9% in the other two studies17,19.

Weight loss was the most prevalent frailty criterion for those transitioning from non-frail to pre-frail, while slowness in walking was the most prevalent frailty criterion in transitions from non-frail to frail. Weight loss and slow walking may serve as precursors for transitioning to physical frailty (as defined in our study). Health providers might consider these as potential indicators to identify older adults at high risk for frailty. Early frailty prevention programs targeted to maintain muscle strength and gait speed with physical exercise, adequate nutrition, and fall prevention may help avoid, or delay, the onset of frailty25. This type of prevention program will likely be a challenge for health professionals working with older Mexican Americans, who are reported to have low levels of physical activity and poor compliance with formal exercise programs26. The development of appropriate preventive programs to delay frailty onset for older Mexican Americans is an important topic for future research.

In contrast to our findings, Fallah and colleagues18 found mobility and gender, but not frailty transition, were significantly associated with 54-month mortality for adults 70 years and older living in New Haven, Connecticut. The inconsistent findings highlight an important issue to consider when interpreting frailty in older adults: that is, different racial groups and geographical locations may impact frailty transition and long-term mortality differently. In addition, different definitions of frailty may result in different mortality predictions. Frailty has been difficult to operationally define in the research literature27. Comprehensive reviews of frailty have been published25,28. This study used the Fried et al.’s frailty definition because of the following reasons: multiple systems (physiological, biological and environmental) that contribute to frailty and its clinical implementation are considered; and this frailty definition is also the most widely cited and used in the U.S. geriatric/gerontology literature18,20,25.

We understand the limitations associated with the modified Frailty Phenotype measure in terms of information related to cognition, psychosocial function, and the environment29. However, our study considers the modified Frailty Phenotype as a measure of physical frailty and the discussion of divergent frailty definitions is beyond the scope of this study. The findings suggest that longitudinal study about frailty are needed for older Mexican Americans. Additionally, preventive programs should be developed to minimize health disparities in frailty transition and long-term mortality in older Mexican Americans.

Study Limitations

As stated above, approaches differ in measuring frailty. Using four instead of five factors may have reduced the sensitivity of the frailty assessment. The Frailty Index of cumulative deficits considers symptoms, signs, diseases, and disabilities as ‘deficits’21 which allow more sensitivity in examining changes in frailty status over time, but requires a level of clinical and medical information not available in the Hispanic EPESE data. The use of self-reported data on medical conditions and depression in this study may lead to biased results. However, self-reported data have been found to be robust.30 The excluded participants in our study were older and less healthy than the included sample; thus, our result may underestimate mortality risk. In addition, the mortality risk generated from our analyses is based on early-stage frailty transitions, however, frailty states may change over time, and the impact of frailty transitions beyond the three-year observation period is unknown. Also, only covariates from Wave 3 were used in the study and we did not control for the effect of changing covariates over time, which may lead to biased result. Finally, a small sample size may lead to less power in the subgroup frailty transition analyses.

Conclusion and Implications

Our results suggest that it is possible for a person’s frailty status to change or reverse. More importantly, this reversal may have a potential long-term positive impact on mortality. Additional longitudinal research is warranted to confirm our results and to better understand how transitions in frailty occur over time. Weight loss and slow walking appear to be factors associated with progression to frailty in this population. Logically, if weight loss and slow walking are associated with the development of frailty, they may also be involved in its reversal. Healthcare investigators and providers have an important role to play in identifying early signs of frailty to reduce or reverse frailty and decrease mortality risk in older Mexican Americans.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Health (R01-AG10939; Principal Investigator: Dr. Markides, and AG017638; Principal Investigator: Dr. Ottenbacher); the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01 MD010355 Principal Investigator: Dr. Ottenbacher); and the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (K01- HD086290; Principal Investigator: Dr. Karmarkar). The authors acknowledge the important contribution of Sarah Toombs Smith, PhD, to editing this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADL

Activities of Daily Living

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- HR

Hazards ratios

- EPESE

Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiological Study of the Elderly

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NDI

National Death Index

- SD

Standard Deviation

APPENDIX

Appendix Figure 1.

Cohort Selection Diagram.

Appendix Table 1.

Comparisons of Characteristics between Included (N=1,171) and Excluded Sample (N=517) (Wave 3).*

| Variables | Included Sample (N=1,171) |

Excluded Sample (n=517) |

Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | P-Value | ||

| Gender | 0.94 | |||||

| Male | 480 | 40.9 | 213 | 41.2 | ||

| Female | 691 | 59.1 | 304 | 58.8 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 77.0 (5.3) | 78.4(6.1) | <0.0001** | ||

| Range | 70-103 | 70-100 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Education (years) | 0.0012** | |||||

| 0 | 166 | 14.2 | 109 | 21.8 | ||

| 1-7 | 726 | 62.0 | 275 | 55.1 | ||

| 8-11 | 154 | 13.2 | 68 | 13.6 | ||

| 12+ | 125 | 10.7 | 47 | 9.4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Marital Status | 0.001** | |||||

| Married | 620 | 52.9 | 230 | 44.5 | ||

| Unmarried | 551 | 47.1 | 287 | 55.5 | ||

|

| ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Range | 12.9-54.7 | 14.4-56.4 | ||||

| <18.5 | 19 | 1.6 | 6 | 1.9 | 0.0338** | |

| 18.5-<25 | 301 | 25.7 | 98 | 31.2 | ||

| 25-<30 | 457 | 39.0 | 95 | 30.3 | ||

| ≥30 | 394 | 33.7 | 115 | 36.6 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cognitive Impairment (MMSE<21) | <0.0001** | |||||

| Yes | 361 | 30.8 | 228 | 51.0 | ||

| No | 810 | 69.2 | 219 | 49.0 | ||

|

| ||||||

| ADL Disabledˆ (Wave 3) | <0.0001* | |||||

| Yes | 91 | 7.8 | 182 | 35.8 | ||

| No | 1080 | 92.2 | 327 | 64.2 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Smoking | 0.7791 | |||||

| Yes | 121 | 10.3 | 50 | 9.9 | ||

| No | 1050 | 89.7 | 456 | 90.1 | ||

| Number of Comorbidities | Mean(SD) | 1.53(1.04) | Mean(SD) | 1.72(1.23) | 0.0009** | |

| Range | 0-5 | Range | 0-6 | |||

Abbreviations: SD (Standard Deviation), BMI (Body Mass Index), MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination), ADL (Activity of Daily Living).

Everyone survived at wave 3

Significant difference at 0.05 level

ADL Disabled was defined as help needed or unable to perform ≥1 of the seven ADL activities from Katz ADL scale (walking, bathing, grooming dressing, eating, transferring, and toileting)34.

Appendix Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazard Model of 15-Year Mortality based on Nine Early Frailty Transition Groups [1995–2013, N=1,080; excluding those who were disable at Wave 3 (n=91; 8% of the original sample)].

| Demographic characteristics | 15-Year Mortality HR(95%CI) |

|---|---|

| Age Group (years) | |

| 65-74 | Ref. |

| 75-84 | 1.83(1.54, 2.19)* |

| 85+ | 3.21(2.45, 4.21)* |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | Ref. |

| Female | 0.70(0.59, 0.83)* |

|

| |

| Education (years) | |

| 0 | Ref. |

| 1-7 | 1.03(0.82, 1.30) |

| 8-11 | 1.38(1.02, 1.88)* |

| 12+ | 1.21(0.87, 1.67) |

|

| |

| Marital Status | |

| Unmarried | Ref. |

| Married | 0.81(0.68, 0.96)* |

|

| |

| BMI Group | |

| 18.5-<25 | Ref. |

| <18.5 | 1.89(1.07, 3.35)* |

| 25-<30 | 0.84(0.70, 1.02)* |

| ≥30 | 0.75(0.62, 0.92)* |

|

| |

| Comorbidity | |

| No | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.21(1.12,1.31)* |

|

| |

| Cognitive Impairment (MMSE<21) | |

| No | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.27(1.07, 1.52)* |

| Smoking | |

| No | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.38(1.07, 1.76)* |

| Nine Frailty Transition& | |

| Nonfrail-nonfrail (N=346) | Ref. |

| Nonfrail-prefrail (N=212) | 1.21(0.97, 1.51) |

| Nonfrail-frail (N=79) | 1.32(0.98, 1.78) |

| Prefrail-nonfrail (N=161) | 1.07(0.83, 1.36) |

| Prefrail-prefrail (N=129) | 1.19(0.91, 1.56) |

| Prefrail-frail (N=56) | 1.59(1.13, 2.24)* |

| Frail-nonfrail (N=27) | 0.96(0.54, 1.73) |

| Frail-prefrail (N=38) | 1.57(1.05, 2.36)* |

| Frail-frail (N=32) | 1.62(1.07, 2.45)* |

95% CI is significant

In Cox regression analysis, there was no violation of the proportionality assumption assessed by the significance of a term of the predictor associated with the logarithm of survival time. The HRs were controlled for the following factors: socio-demographics, BMI, ADL disability, cognitive impairment and comorbidities.

ADL Disabled was defined as help needed or unable to perform ≥1 of the seven ADL activities from the Katz ADL scale (walking, bathing, grooming dressing, eating, transferring, and toileting)34.

Abbreviations: HR (Hazard Ratio), CI (Confidence Interval), BMI (Body Mass Index), MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination), ADL (Activity of Daily Living), SD (Standard Deviation).

Footnotes

Jaymar Hydraulic Dynamo-meter model #5030J1; J.A. Preston Corp., Jackson, MI

References

- 1.Snih Al S, Graham JE, Ray LA, Samper-Ternent R, Markides KS, Ottenbacher KJ. Frailty and incidence of activities of daily living disability among older Mexican Americans. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(11):892–897. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cano C, Samper-Ternent R, Al Snih S, Markides K, Ottenbacher KJ. Frailty and cognitive impairment as predictors of mortality in older Mexican Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(2):142–147. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0104-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cawthon PM, Marshall LM, Michael Y, Dam TT, Ensrud KE, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Frailty in older men: prevalence, progression, and relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1216–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, Fink HA, Stone KL, Cauley JA, et al. Frailty and risk of falls, fracture, and mortality in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):744–751. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ottenbacher KJ, Graham JE, Al Snih S, Raji M, Samper-Ternent R, Ostir GV, et al. Mexican Americans and frailty: findings from the Hispanic established populations epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):673–679. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandeen-Roche K, Seplaki CL, Huang J, Buta B, Kalyani RR, Varadhan R, Xue QL, Walston JD, Kasper JD, et al. Frailty in older adults: A nationally representative profile in the United States. J Gerontol A Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1427–1424. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv133. doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glv133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health (BR) Secretariat of Health Care. Department of Basic Attention. Aging and health of the elderly. Brasília, DF: Ministry of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espinoza SE, Hazuda HP. Frailty in older Mexican American and European American adults: Is there an ethnic disparity? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(9):1744–1749. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crist JD, Koerner KM, Hepworth JT, Pasvogel A, Marshall CA, Cruz TP, et al. Differences in transitional care provided to Mexican American and Non-Hispanic White older adults. J Transcult Nurs. 2017;28(2):159–67. doi: 10.1177/1043659615613420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ottenbacher KJ, Ostir GV, Peek MK, Snih SA, Raji MA, Markides KS. Frailty in older Mexican Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1524–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. pp. 25–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. The next four decades: The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Retrieved on 4/30/2017 from https://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf.

- 14.Campbell JA. Current Population Reports: Health Insurance Coverage 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce; US Census Bureau; 2008. (Publication P60-208). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alemayehu B, Warner KE. The lifetime distribution of health care costs. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(3):627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ottenbacher KJ, Ostir GV, Peek MK, Goodwin JS, Markides KS. Diabetes Mellitus as a risk factor for hip fracture in Mexican American older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(10):M648–M653. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.10.m648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):418–423. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallah N, Mitnitski A, Searle SD, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. Transitions in frailty status in older adults in relation to mobility: a multistate modeling approach employing a deficit count. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(3):524–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollack LR, Litwack-Harrison S, Cawthon PM, Ensrud K, Lane NE, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Patterns and predictors of frailty transitions in older men: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2473–2479. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston JD, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J GerontolThe Journals of Gerontology: Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–727. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe NM. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff LS. The CED-S Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bird HR, Canino G, Stipec MR, Shrout P. Use of the Mini-mental State Examination in a probability sample of a Hispanic population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175(12):731–737. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levers MJ, Estabrooks CA, Ross Kerr JC. Factors contributing to frailty: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(3):282–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brawley LR, Rejeski WJ, King AC. Promoting physical activity for older adults: The challenges for changing behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(3):172–183. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen HJ. In search of the underlying mechanisms of frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(12):M706–M708. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.12.m706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. How might deficit accumulation give rise to frailty? J Frailty Aging. 2012;1(1):8–12. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nam S, Al Snih S, Markides KS. A concordance of self-reported and performance-based assessments of mobility as a mortality predictor for older Mexican Americans. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(3):433–439. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]