Abstract

Mice harboring Notch2 mutations replicating Hajdu-Cheney syndrome (Notch2tm1.1ECan) have osteopenia and exhibit an increase in splenic marginal zone B cells with a decrease in follicular B cells. Whether the altered B-cell allocation is responsible for the osteopenia of Notch2tm1.1ECan mutants is unknown. To determine the effect of NOTCH2 activation in B cells on splenic B-cell allocation and skeletal phenotype, a conditional-by-inversion (COIN) Hajdu-Cheney syndrome allele of Notch2 (Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN) was used. Cre recombination generates a permanent Notch2ΔPEST allele expressing a transcript for which sequences coding for the proline, glutamic acid, serine, and threonine–rich (PEST) domain are replaced by a stop codon. CD19-Cre drivers were backcrossed into Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN to generate CD19-specific Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mutants and control Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN littermates. There was an increase in marginal zone B cells and a decrease in follicular B cells in the spleen of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice, recapitulating the splenic phenotype of Notch2tm1.1ECan mice. The effect was reproduced when the NOTCH1 intracellular domain was induced in CD19-expressing cells (CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice). However, neither CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST nor CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice had a skeletal phenotype. Moreover, splenectomies in Notch2tm1.1ECan mice did not reverse their osteopenic phenotype. In conclusion, Notch2 activation in CD19-expressing cells determines B-cell allocation in the spleen but has no skeletal consequences.

Notch are transmembrane receptors that determine cell fate and function. Notch receptors are activated after their interactions with ligands of the Jagged and Delta-like families residing in neighboring cells.1 The interactions lead to the proteolytic cleavage of the Notch receptor and the release of its intracellular domain.2 The Notch intracellular domain (NICD) translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a ternary complex with recombination signal binding protein for Ig of κ region (RBPJκ) and Mastermind-like.3, 4, 5 As a consequence, inhibitors of transcription are displaced and coactivators are recruited, and Notch target genes of the hairy enhancer of split (Hes) and Hes-related with YRPW motif families are transcribed.6 Although the four Notch receptors share structural properties, their function is not redundant. This has been attributed to distinct patterns of cellular expression, structural differences, and specific interactions of each NICD with RBPJκ.7

Notch1 is expressed preferentially by T cells, and its inactivation prevents T-cell development and causes ectopic B-cell formation; Notch1 gain of function has been associated with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.8, 9 Notch2 is expressed preferentially by B cells, and its gain of function has been associated with B-cell lymphomas and lymphomas of the marginal zone of the spleen.10, 11 Notch2 signaling is required for marginal zone (MZ) B-cell development.12, 13 NOTCH2 loss-of-function mutations in humans, Notch2 haploinsufficiency, or the conditional inactivation of either Notch2 or Rbpjκ in CD19-expressing cells all result in a reduction in the B-cell population of the MZ of the spleen.14, 15, 16 Accordingly, expression of the NOTCH2 NICD in CD19-expressing cells leads to the reallocation of B cells to the MZ of the spleen.17

Hajdu-Cheney syndrome (HCS) is a rare genetic disease characterized by craniofacial developmental abnormalities, acroosteolysis, and osteoporosis; occasionally, it can present with splenomegaly.18, 19, 20 HCS is associated with point mutations or short deletions in exon 34 of NOTCH2, leading to the generation of stop codons upstream of the proline (P), glutamic acid (E), serine (S), and threonine (T)–rich (PEST) domain, which is necessary for the degradation of NOTCH2.21, 22, 23, 24, 25 As a consequence, the mutations result in the translation of a stable protein product and gain-of-Notch2 function.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27

To gain an understanding of the pathophysiology of HCS, a mouse model harboring a Notch2 mutation (6955C>T) in exon 34, upstream of the PEST domain (hence reproducing the HCS mutation), was engineered and termed Notch2tm1.1ECan.26 The Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant mouse exhibits osteopenia as well as a B-cell phenotype, with reallocation of B cells to the MZ of the spleen.28 Although B cells are presumed to affect skeletal homeostasis, it is not known whether the osteopenia of the Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant is related to the observed alteration in B-cell lineage allocation.29, 30, 31

Splenic as well as bone marrow B cells are considered a source of receptor activator of nuclear factor κ B ligand (RANKL), and the production of RANKL by B cells contributes to the bone loss induced by estrogen deficiency and the bone erosion of rheumatoid arthritis.32, 33, 34 These observations suggest a role for B-cell–derived RANKL in osteoclastogenesis, but it is not known whether the effect of Notch2 on B-cell allocation in the spleen influences the skeleton and whether the reallocation of B cells is a Notch2-specific function. To address these questions, Notch2 was activated in CD19-expressing B cells by crossing CD19Cre mice with a conditional-by-inversion (COIN) mouse model of HCS (Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN).35 The model was designed to introduce a stop codon in exon 34 of Notch2 after Cre-mediated recombination (Notch2ΔPEST), resulting in the translation of a truncated NOTCH2 protein and, thus, mimicking the genetic defect associated with HCS. The effects of Notch1 gain of function were also examined by crossing CD19Cre mice with Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(Notch1)Dam/J (defined herein as RosaNotch1) mice, where a loxP flanked STOP cassette is placed between the NOTCH1-NICD coding sequence and Gt(Rosa)26 regulatory elements.36 Mice were examined for B-cell allocation in the spleen and bone marrow by flow cytometry and for skeletal phenotypic changes by microcomputed tomography (μCT).

Materials and Methods

Mouse Models

Notch2 COIN Mice

The Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN mouse model was generated by introducing an artificial COIN intron into exon 34 of Notch2 in the antisense strand, as recently described.35, 37 Before Cre recombination, the COIN module is removed by splicing of the precursor mRNA to generate a Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN transcript that is indistinguishable from the Notch2 wild-type (Notch2WT) mRNA. In the presence of Cre recombinase, the COIN module is brought into the sense strand, causing the irreversible inversion of the allele. The resulting allele, which was termed Notch2ΔPEST, encodes for a NOTCH2 mutant protein truncated at lysine 2384 lacking the PEST domain.35 After the removal of the neo selection cassette, Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN mice were maintained in a 129SvJ/C57BL/6J background.

Induction of the HCS Mutation in the Germline and in CD19-Expressing Cells

To achieve systemic inversion of the Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN allele, F1 heterozygous Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/WT male mice were bred with female mice expressing Cre under the control of the Hprt promoter (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME).38 This resulted in the germline inversion of the COIN module and consequent generation of mice heterozygous for the Notch2ΔPEST allele.35 The latter were backcrossed into a C57BL/6J genetic background and crossed with wild-type C57BL/6J mice to generate Notch2ΔPEST/WT experimental and wild-type control littermates for phenotypic characterization.

C57BL/6J mice in which the Cre coding sequence was inserted into the endogenous CD19 locus (CD19Cre; Jackson Laboratory) were used to express Cre recombinase in the B-cell lineage.39 To study the activation of the HCS mutation in CD19-expressing cells, the Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN allele was introduced into CD19Cre/WT mice, and CD19Cre/WT;Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN mice were crossed with Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN mice for the generation of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST experimental and Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN littermate controls.

Induction of the NOTCH1-NICD in CD19-Expressing Cells

To induce the NOTCH1-NICD in CD19 cells, RosaNotch1/WT mice in a C57BL/6J genetic background (Jackson Laboratory) were used.36, 40 In this model, the Gt(Rosa)26 locus is targeted with a DNA construct encoding the NOTCH1-NICD, preceded by a loxP-flanked STOP cassette, cloned downstream of the Gt(Rosa)26 promoter, so that the NICD is expressed on excision of the STOP cassette by Cre recombination. Homozygous RosaNotch1/Notch1 mice were crossed with heterozygous CD19Cre/WT mice to generate CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT experimental mice and RosaNotch1/WT littermate controls.

Hajdu-Cheney Global Notch2tm1.1ECan Mutant Mice

To generate a global mutant mouse model of HCS, a 6955C>T substitution was introduced into the mouse Notch2 locus by homologous recombination, as previously reported.26 After the removal of the neomycin selection cassette and confirmation of the Notch2 mutation by sequencing of genomic DNA, mice were backcrossed into a C57BL/6J background for eight or more generations. Heterozygous Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant and control sex-matched littermate controls were obtained by crossing heterozygous mutant Notch2tm1.1ECan mice with wild-type mice.

Genotyping and Verification of LoxP Recombination

Allelic composition was determined by PCR analysis of tail DNA with specific primers (all primers from Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, CA) (Table 1). Inversion of the COIN module in spleen and bone marrow cells from CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice and deletion of the STOP cassette in spleen cells from CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice were documented by PCR analysis of genomic DNA with specific primers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers Used for Genotyping and Determination of Cre-Mediated Recombination by PCR

| Allele | Strand | Sequence | Amplicon size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping | |||

| CD19Cre | Forward | 5′-GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC-3′ | 100 |

| Reverse | 5′-GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT-3′ | ||

| CD19WT | Forward | 5′-CCTCTCCCTGTCTCCTTCCT-3′ | 500 |

| Reverse | 5′-TGGTCTGAGACATTGACAATCA-3′ | ||

| Fabp1 | Forward | 5′-TGGACAGGACTGGACCTCTGCTTTCC-3′ | 200 |

| Reverse | 5′-TAGAGCTTTGCCACATCACAGGTCAT-3′ | ||

| HprtWT | Forward | 5′-TTTCTATAGGACTGAAAGACTTGCTC-3′ | 200 |

| Reverse | 5′-CACAGTAGCTCTTCAGTCTGATAAAA-3′ | ||

| HprtCre | Forward | 5′-GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC-3′ | 100 |

| Reverse | 5′-GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT-3′ | ||

| Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN | Forward | 5′-CCGGGCCGCGACTGAAACCCTAG-3′ | 330 |

| Reverse | 5′-CCACCACCTCCAGGAGTTGGGC-3′ | ||

| Notch2tm1.1ECan | Forward Nch2Lox gtF | 5′-CCCTTCTCTCTGTGCGGTAG-3′ | WT = 310 Notch2tm1.1ECan = 400 |

| Reverse Nch2Lox gtR | 5′-CTCAGAGCCAAAGCCTCACTG-3′ | ||

| Notch2WT | Forward | 5′-GCTCAGACCATTGTGCCAACCTAT-3′ | 100 |

| Reverse | 5′-CAGCAGCATTTGAGGAGGCGTAA-3′ | ||

| RosaNotch1 | Forward | 5′-GGAGCGGGAGAAATGGATATG-3′ | WT = 600 RosaNotch1 NICD = 250 |

| Reverse WT | 5′-AAAGTCGCTCTGAGTTGTTATTG-3′ | ||

| Reverse RosaNotch1 NICD | 5′-GCGAAGAGTTTGTCCTCAACC-3′ | ||

| LoxP recombination | |||

| Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN | Forward | 5′-GTACTTCAGCACAGTTTTAGAGAAC-3′ | Not recombined and not detected Recombined = 250 |

| Reverse | 5′-GTGAGTCACCCGCCGGATGTC-3′ | ||

| RosaNotch1 | Forward | 5′-TTCGCGGTCTTTCCAGTGG-3′ | Not recombined = 500 Recombined = 300 |

| Reverse absent loxP recombination | 5′-AGCCTCTGAGCCCAGAAAGC-3′ | ||

| Reverse present loxP recombination | 5′-GCCGACTGAGTCCTCGCC-3′ | ||

NICD, Notch intracellular domain; WT, wild type.

Splenectomies

Notch2tm1.1ECan global mutants and control littermate mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane (Butler Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH), and a dorsal incision was made midway between the rib cage and the hip. The spleen was removed after the ligation of the gastrosplenic ligament and splenic blood vessels by transecting the ligament distal of the ligated vessels, and the abdominal wall was closed. For sham interventions, the spleen was exposed but not resected. Animals were given buprenorphine (Butler Scheim Animal Health), 50 μg, before and immediately after surgery, and then 100 μg twice daily for 48 hours for analgesia. Mice were sacrificed 1 month after the intervention for the characterization of their skeletal phenotype, performed in a blinded manner.

Animals were housed in a pathogen-free facility in groups of one to five per cage and fed commercially available chow (ENVIGO, Madison, WI). Animals appeared healthy during the study, were not immunocompromised, and did not exhibit obvious adverse events. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UConn Health (Farmington, CT).

Immunofluorescence

To generate frozen sections for immunofluorescence, spleens were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde overnight, exposed to 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C, and embedded in OCT medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Sections (7 μm thick) were cut, hydrated in phosphate-buffered saline, and treated with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated anti-CD169(MOMA−1) clone or phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-IgM antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) at a 1:100 dilution. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and mounted for fluorescence imaging. Sections were viewed on a Leica fluorescence microscope (model DMI6000B), and collected images were processed using the Leica Application Suite x 1.5.1.1387 (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Flow Cytometry

To release splenocytes, spleens were disrupted by gentle pressure of the organ between two glass slides. Bone marrow cells were obtained by flushing femurs and tibias with a 26-gauge needle, after the removal of both epiphyseal ends. After the lysis of erythrocytes using a buffer containing 150 mmol/L ammonium chloride, 10 mmol/L potassium chloride, 0.1 mmol/L EDTA (ACK lysis buffer), approximately 4 × 106 cells per mouse were collected in cell-staining medium containing 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Hampton, NH) in Hanks' balanced salt solution. Flow cytometry was performed using the following antibodies: anti-CD19, phycoerythrin/Dazzle 594, clone 6D5, anti-CD117 Brilliant Violet 421, clone 2B8, anti-IgM phycoerythrin, clone RMM-1, anti-CD45 allophycocyanin-Cy7, clone 3D-F11, anti-CD23 Brilliant Violet 510, clone B3B4, anti-CD21/CD35 phycoerythrin-Cy7, clone 7G9 (all from BioLegend), and anti-CD45R Alexa Fluor 700, clone RA3-6B2 (eBioscience, Santa Clara, CA). Cells were stained for live-dead cells with Zombie UV dye (BioLegend) at a 1:200 dilution, incubated with antibodies at a concentration of 0.1 μg/106 cells in 100 μL staining medium for 1 hour on ice, washed in cell staining medium, and analyzed using a BD-LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). After gating for live-dead cell staining and background staining using isotype controls, the relative number of various cell populations was analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.2 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

RNA Extraction from Spleen and Bone Marrow Cells and RNA Integrity

Splenocytes were released after disruption of the spleen, and bone marrow cells were harvested by centrifugation of femurs after removal of the distal epiphysis. In one experiment, cells from wild-type C57BL/6J mice were enriched in CD19-expressing splenocytes (CD19+) by magnetic positive selection of spleen suspensions using an autoMacs proseparator system (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). Splenocytes depleted of CD19-expressing cells (CD19−) after separation also were collected. Total RNA was extracted from homogenized splenocytes, bone marrow cells, and CD19+ and CD19− spleen cells with an RNeasy kit, in accordance with manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The integrity of the RNA was tested by microfluidic electrophoresis (Experion system; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and only RNA with a quality indicator number of seven or higher was used for analysis of gene expression.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Equal amounts of RNA were reverse transcribed using iScript RT-PCR kit (Bio-Rad), according to manufacturer's instructions, and amplified in the presence of specific primers (all primers from Integrated DNA Technologies) (Table 2) and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), at 60°C for 35 cycles.41, 42 Transcript copy number was estimated by comparing to a serial dilution of cDNA for Dll1 (Emmanuelle Six, Institut Imagine, Paris, France), Dll3, Dll4, and Jag2 (GE Healthcare Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO), Cre, Jag1, and Notch2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Hes1 and Tnfrsf11b, encoding for osteoprotegerin, and ribosomal protein L38 (Rpl38; ATCC, Manassas, VA), Hes5 (from Ryoichiro Kageyama, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), Notch1 and Notch1NICD (Jeffrey S. Nye, Janssen Research and Development Labs, LaJolla, CA), Notch4 (Yasuaki Shirayoshi, Tottori University, Tottori, Japan), and Tnfsf11 (Source BioScience, Nottingham, UK).43, 44, 45, 46 Notch2ΔPEST transcripts were detected with primers that generate an amplicon straddling the artificial splice junction generated within exon 34 of the targeted Notch2 locus on inversion of the COIN module (Table 2). Primers are specific for the Notch2ΔPEST mRNA and do not recognize the wild-type Notch2 transcript or the Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN mRNA before COIN inversion. Notch2ΔPEST and Notch3 copy number was estimated by comparison to a serial dilution of an approximately 200-bp synthetic DNA template (Integrated DNA Technologies) cloned into pcDNA3.1(−) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by isothermal single-reaction assembly using commercially available reagents (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA).47 To monitor for the efficiency of the COIN inversion, primers designed to amplify a sequence of the Notch2 transcript coding for the PEST domain were used, and the respective PCR product was termed Notch2PEST (Table 2). These primers allow the detection, by real-time quantitative RT-PCR, of the transcripts for Notch2WT and Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN, but not for Notch2ΔPEST, because the latter lacks the sequences coding for the PEST domain. Notch2PEST copy number was measured by comparing with a serial dilution of Notch2 cDNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Table 2.

Primers Used for RT-qPCR Determinations

| Gene | Sequence | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| Cre | F: 5′-TGTTAATCCATATTGGCAGAACGA-3′ | X03453 |

| R: 5′-ATCCATCGCTCGACCAGTTTA-3′ | ||

| Dll1 | F: 5′-CTCTTCCCCTTGTTCTAAC-3′ | NM_007865 |

| R: 5′-ACAGTCATCCACATTGTC-3′ | ||

| Dll3 | F: 5′-TCTATCTTGTCCCTTCTCTATCA-3′ | NM_007866 |

| R: 5′-AATCATTCAGGCTCCATCTC-3′ | ||

| Dll4 | F: 5′-TGACAAGAGCTTAGGAGAG-3′ | NM_019454 |

| R: 5′-GCTTCTCACTGTGTAACC-3′ | ||

| Hes1 | F: 5′-ACCAAAGACGGCCTCTGAGCACAGAAAGT-3′ | NM_008235 |

| R: 5′-ATTCTTGCCCTTCGCCTCTT-3′ | ||

| Hes5 | F: 5′-GGAGATGCTCAGTCCCAAGGAG-3′ | NM_010419 |

| R: 5′-TGCTCTATGCTGCTGTTGATGC-3′ | ||

| Jag1 | F: 5′-TGGGAACTGTTGTGGTGGAGTCCG-3′ | NM_013822 |

| R: 5′-GTGACGCGGGACTGATACTCCT-3′ | ||

| Jag2 | F: 5′-AAGGTGGAAACAGTTGT-3′ | NM_010588 |

| R: 5′-CACGGGCACCAACAG-3′ | ||

| Notch1 | F: 5′-GTCCCACCCATGACCACTACCCAGTTC-3′ | NM_008714 |

| R: 5′-GGGTGTTGTCCACAGGTGA-3′ | ||

| Notch1NICD | F: 5′-GTGCTCTGATGGACGACAAT-3′ | NM_008714 |

| R: 5′-GCTCCTCAAACCGGAACTTC-3′ | ||

| Notch2PEST | F: 5′-CCATTGTGCCAACCTATCAT-3′ | NM_010928 |

| R: 5′-TTGAGGAGGCGTAACTGT-3′ | ||

| Notch2ΔPEST | F: 5′-GGCTTTCCCACCTACCAT-3′ | Not applicable |

| R: 5′-TAGTCGGGCACGTCGTAG-3′ | ||

| Notch2 | F: 5′-TGACGTTGATGAGTGTATCTCCAAGCC-3′ | NM_010928 |

| R: 5′-GTAGCTGCCCTGAGTGTTGTGG-3′ | ||

| Notch3 | F: 5′-CCGATTCTCCTGTCGTTGTCTCC-3′ | NM_008716 |

| R: 5′-TGAACACAGGGCCTGCTGAC-3′ | ||

| Notch4 | F: 5′-CCAGCAGACAGACTACGGTGGAC-3′ | NM_010929 |

| R: 5′-GCAGCCAGCATCAAAGGTGT-3′ | ||

| Rpl38 | F: 5′-AGAACAAGGATAATGTGAAGTTCAAGGTTC-3′ | NM_001048057; NM_001048058; NM_023372 |

| R: 5′-CTGCTTCAGCTTCTCTGCCTTT-3′ | ||

| Tnfrsf11b | F: 5′-CAGAAAGGAAATGCAACACATGACAAC-3′ | NM_009399 |

| R: 5′-GCCTCTTCACACAGGGTGACATC-3′ | ||

| Tnfsf11 | F: 5′-TATAGAATCCTGAGACTCCATGAAAAC-3′ | NM_011613 |

| R: 5′-CCCTGAAAGGCTTGTTTCATCC-3′ |

GenBank accession numbers identify the transcripts recognized by primer pairs (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore).

F, forward; R, reverse; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

Amplification reactions were conducted in CFX96 real-time quantitative RT-PCR detection systems (Bio-Rad), and fluorescence was monitored during every PCR cycle at the annealing step. Data are expressed as copy number corrected for Rpl38 expression, estimated by comparison with a serial dilution of Rpl38 (ATCC).48

Microcomputed Tomography

Femoral microarchitecture was determined using a microcomputed tomography instrument (Scanco μCT 40; Scanco Medical AG, Brütisellen, Switzerland), which was calibrated periodically using a phantom provided by the manufacturer.49, 50 Femurs were scanned in 70% ethanol at high resolution, energy level of 55 kVp, intensity of 145 μA, and integration time of 200 milliseconds. A total of 100 slices at midshaft and 160 slices at the distal metaphysis were acquired at an isotropic voxel size of 216 μm3 and a slice thickness of 6 μm, and chosen for analysis. Trabecular bone volume fraction (bone volume/total volume) and microarchitecture were evaluated starting approximately 1.0 mm proximal from the femoral condyles. Contours were manually drawn every 10 slices, a few voxels away from the endocortical boundary, to define the region of interest for analysis, whereas the remaining slice contours were iterated automatically. Total volume, bone volume, bone volume fraction, trabecular thickness, trabecular number, connectivity density, structure-model index, and material density were measured in trabecular regions using a gaussian filter (σ = 0.8) and user-defined thresholds.49, 50 For analysis of cortical bone, contours were iterated across 100 slices along the cortical shell of the femoral midshaft, excluding the marrow cavity. Analysis of bone volume/total volume, porosity, cortical thickness, total cross-sectional and cortical bone area, periosteal and endosteal perimeter, and material density was conducted using a gaussian filter (σ = 0.8, support = 1) with operator-defined thresholds. Technical personnel were blinded to the identity of the animals during analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical differences were determined by t-test for pairwise or two-way analysis of variance, with Holm-Šídák post-hoc analysis for multiple comparisons. To ensure normal data distribution, a Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted; and to ensure equal variance of the data, a Brown-Forsythe test was applied.

Results

Expression Pattern of Notch Receptors and Ligands in the Spleen and Bone Marrow

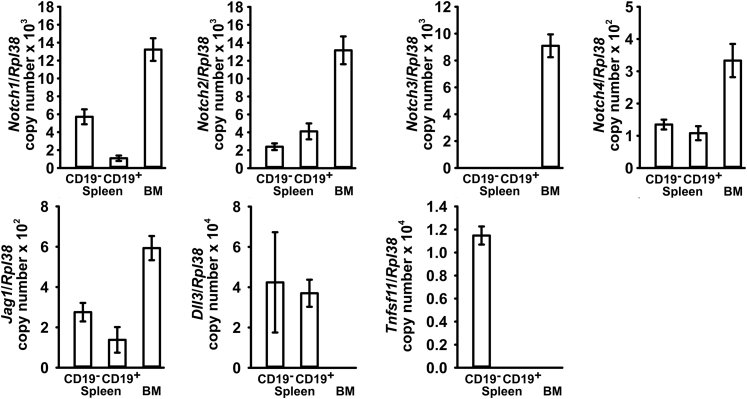

To determine the potential role of Notch receptors and ligands in cellular events in the spleen and bone marrow environment, the expression pattern of Notch receptors and ligands in these organs was determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Notch1, 2, and 4, but not Notch3, were expressed by CD19− and CD19+ cells of the spleen (Figure 1). All four Notch receptors were expressed by bone marrow cells. Jagged1 (Jag1) was expressed by CD19− and CD19+ spleen cells as well as by bone marrow cells, and Delta-like 3 (Dll3) was expressed only by spleen cells, whereas Jag2, Dll1, and Dll4 were not detected in either spleen or bone marrow cells. RANKL, encoded by Tnfsf11, was expressed by CD19− but not by CD19+ spleen cells (Figure 1), and its transcript expression in CD19+ bone marrow cells was detected inconsistently (data not shown). Osteoprotegerin expression was not detected in either spleen or bone marrow cells.

Figure 1.

Expression of Notch receptors, cognate ligands, and Tnfsf11 in the spleen and bone marrow (BM). Spleens and femurs were dissected from 7- and 10-week–old wild-type male mice, respectively. Cellular fractions enriched or depleted of CD19-expressing splenocytes (CD19+ or CD19−, respectively) were obtained from spleen suspensions, and bone marrow cells were harvested from femurs, by centrifugation. Total RNA was extracted from isolated cells, and mRNA was quantified by real-time quantitative RT-PCR in the presence of specific primers. Data are expressed as Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, Notch4, Jag1, Dll3, and Tnfsf11 copy number, corrected for Rpl38 expression. Jag2, Dll1, Dll4, and Tnfrsf11b were not detected in any cell preparation shown. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 3 splenocytes; n = 4 bone marrow biological replicates.

Inversion of the Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN Allele in the Germline Increases Marginal Zone B Cells

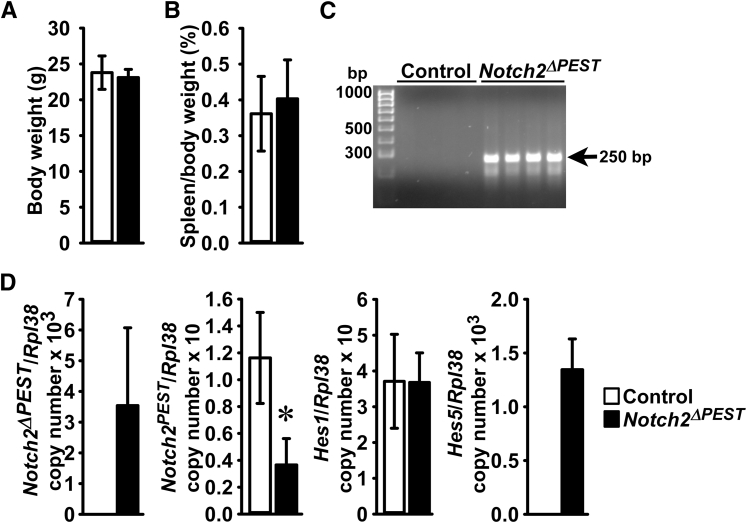

To validate the Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN mouse as a model of HCS, the spleen phenotype of Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice was determined. These mice were generated by crossing Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/WT male mice with heterozygous HprtCre female mice, which brings about the inversion of the COIN module in the germline, causing Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice. These mice were crossed with wild-type mice to obtain Notch2ΔPEST/WT and control wild-type littermates. Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice appeared healthy, and their weight and spleen weight were not different from controls (Figure 2). COIN inversion was documented by the presence of the Notch2ΔPEST allele in DNA from tails of Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of total RNA from spleen documented the expression of the Notch2ΔPEST transcript in mutant mice but not in control littermates. The levels of Notch2 transcripts that retain the sequence coding for the PEST domain (Notch2PEST) were approximately 60% lower in Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice than in controls, confirming the inversion event and demonstrating that transcription is interrupted upstream of the PEST domain. The approximately 60% reduction is congruent with the heterozygosity of the Notch2ΔPEST allele and indicates that the Notch2ΔPEST and Notch2WT alleles have a comparable level of expression. These effects were associated with increased transcript levels for Hes5, suggesting enhanced Notch signaling (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

General appearance of Notch2ΔPEST/WT germline mice and Notch signaling in the spleen. Weight, spleen weight, documentation of Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN inversion, and expression of Notch target genes in control and germline Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice. A and B: Body weight (A) and ratio of spleen/body weight (B) of Notch2ΔPEST/WT and control 2-month–old male mice. C: DNA was extracted from tails, and Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN inversion was documented by gel electrophoresis of PCR products obtained with primers specific for the Notch2ΔPEST allele. The arrow indicates the position of the 250-bp amplicon. D: Total RNA was extracted from spleens, and expression of the Notch2ΔPEST, Notch2PEST, Hes1, and Hes5 mRNA was determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Transcript levels are reported as copy number corrected for Rpl38 mRNA levels. Two technical replicates were used for each real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Data for Hes1 mRNA were obtained from 2- and 2.5-month–old mice. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A, B, and D). n = 4 biological replicates (A and B); n = 3 control and n = 4 Notch2ΔPEST/WT biological replicates for Notch2ΔPEST, Notch2PEST and Hes5 expression (D); n = 5 control and n = 7 Notch2ΔPEST/WT biological replicates for Hes1 mRNA levels (D). ∗P < 0.05 versus control (t-test).

Flow cytometry of spleen cells from 2-month–old male Notch2ΔPEST/WT and littermate control sex-matched mice demonstrated an approximately threefold increase in the percentage of MZ B cells identified as B220+IgM+CD21/35highCD23− cells in Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice compared with sex-matched control mice (Figure 3). Accordingly, the mean fluorescence intensity was increased 1.3-fold. In association with this increase in MZ B-cell subset, there was a modest decrease in the percentage of follicular (B220+IgM+CD21/35intCD23+) B cells in Notch2ΔPEST/WT compared with control mice. The results confirm the spleen phenotype of global Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant mice28 and validate the Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN model for the study of B-cell phenotypic changes.

Figure 3.

Splenic B-cell allocation in Notch2ΔPEST/WT germline mice. Flow cytometry of spleen cells from control and germline Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice. A: Representative dot plot of flow cytometry of spleen cells from 2-month–old male Notch2ΔPEST/WT and control sex-matched littermates. Cells were stained with anti-CD21/35 and anti-CD23 antibodies. Frequency of CD21/35highCD23− marginal zone (MZ) B cells and CD21/35intCD23+ follicular B cells gated on B220+/IgM+ B-cell populations is shown. Values represent the percentage of MZ B cells and follicular B cells for four biological replicates. B: Histogram of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the CD21/35 cell population from 2-month–old germline Notch2ΔPEST/WT and control mice. C: Bar graph of MFI of the CD21/35 cells for control and germline Notch2ΔPEST/WT mice. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A and C). n = 4 biological replicates for control and experimental mice (A and C). ∗P < 0.05 versus control (t-test).

Inversion of the Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN Allele in CD19 B Cells Causes an Expansion of Marginal Zone B Cells

To determine whether the increased B-cell population in the MZ of mice carrying the HCS mutation was driven by a direct effect of Notch2 in B cells, the Notch2ΔPEST mutation was introduced into CD19-expressing cells. For this purpose, CD19Cre/WT;Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN and Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN mice were crossed to generate CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice and littermate Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN controls. In an initial experiment, flow cytometry of the spleen and bone marrow of CD19Cre/WT demonstrated no differences in B-cell populations when compared with wild-type littermate controls (data not shown). Flow cytometry demonstrated no differences in bone marrow B-cell populations or follicular B cells in the spleen between Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN and wild-type littermate controls. However, a decrease in MZ B cells from (means ± SD; n = 4) 5.9% ± 1.4% in controls to 2.1% ± 0.3% (P < 0.05) in Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN was observed.

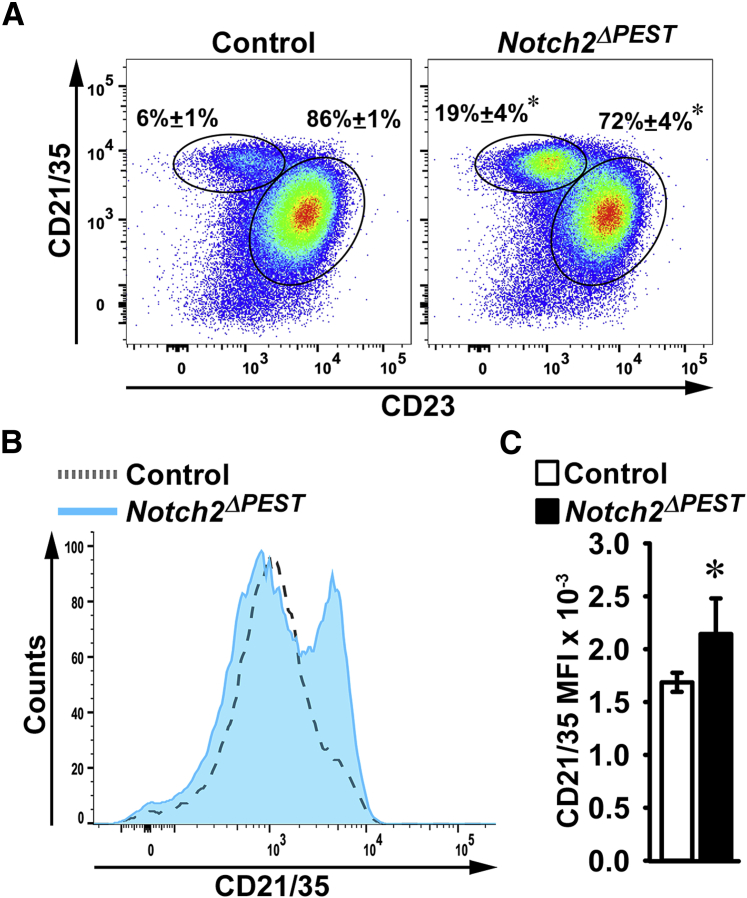

The general appearance and weight of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice were not different from controls, although the spleen of female mice was relatively larger than that of controls (Figure 4). Inversion of the COIN allele was detected in DNA from the spleen and bone marrow of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice but not of littermate controls (Figure 4). Accordingly, the Notch2ΔPEST transcript was detected only in the spleen of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice, documenting the induction of the HCS mutation in CD19-expressing cells. The presence of the Notch2ΔPEST mRNA was associated with an approximately 50% reduction of Notch2PEST mRNA and increased transcript levels for Hes1 and Hes5 in the spleen, demonstrating increased Notch2 signaling (Figure 4). A lesser degree of Notch2ΔPEST expression was observed in bone marrow cells from CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice, and no appreciable reduction in Notch2PEST mRNA was noted. This resulted in a lack of induction of the Notch target genes Hes1 and Hes5 in the marrow compartment. Although Notch2 is expressed by bone marrow cells (Figure 1), the results indicate a small degree of Notch2ΔPEST induction in CD19-expressing bone marrow cells. This was attributed to the greater expression of Cre recombinase in the spleen than in the bone marrow of CD19Cre mice.39, 51 In accordance with these observations, Cre mRNA levels were (means ± SD; n = 8 to 11 Cre copy number/Rpl38) 5.7 ± 2.4 in the spleen and 1.4 ± 0.7 in the bone marrow (P < 0.05) of CD19Cre mice. To ensure B-cell–specific Cre recombination, Cre mRNA transcripts were measured in multiple tissues from CD19Cre;Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN]; values (means ± SD; n = 3; spleen transcripts normalized to 1) for Cre copy number/Rpl38 were 1.0 ± 0.6 for spleen, 0.3 ± 0.1 for lung, 0.25 ± 0.1 for femur, and 0.02 ± 0.03 for thymus. Cre mRNA was undetectable in the kidney, liver, and brain. The expression in the femur may represent contamination of the samples by residual bone marrow cells.

Figure 4.

General appearance of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice and Notch signaling in the spleen and bone marrow. Weight, spleen weight, documentation of Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN inversion, and expression of Notch2 target genes in control and CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice. A and B: Body weight (A) and ratio of spleen weight/body weight (B) of 2-month–old control and CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST male and female mice. C: DNA was extracted from spleen or bone marrow cells of 2-month–old male CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST and Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN control mice. Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN inversion was demonstrated by gel electrophoresis of PCR products obtained with primers specific for the Notch2ΔPEST allele. The arrow indicates the position of the 250-bp amplicon. D: Total RNA was extracted from spleen or bone marrow cells of 2-month–old CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST and control Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN mice, and gene expression was measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Notch2ΔPEST, Notch2PEST, Hes1, and Hes5 mRNA copy number corrected for Rpl38 expression are shown. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A, B, and D). n = 3 Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN controls and n = 4 CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST for male mice; n = 4 Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN controls and n = 3 CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST for female mice (A and B); n = 4 Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN controls and n = 3 CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice biological replicates (D). ∗P < 0.05 versus control (t-test).

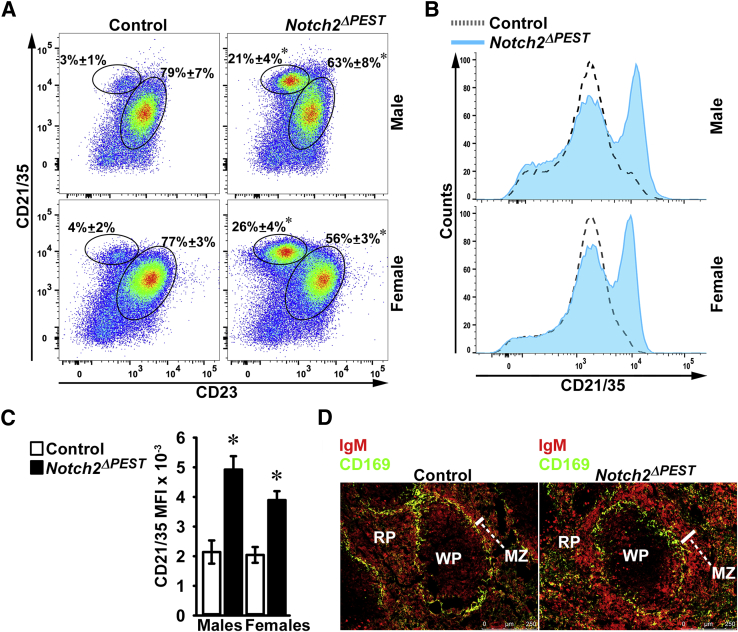

Flow cytometry of B cells isolated from the bone marrow demonstrated that the frequency of pre–pro-B (B220+CD19−CD117−IgM−), pro-B (B220+CD19+CD117+IgM−), pre-B (B220+CD19+CD117−IgM−), and immature (B220+CD19+CD117−IgM+) B cells was not different between CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST and control mice of either sex (Table 3). Flow cytometry of spleen cells revealed a sixfold to sevenfold increase in MZ B cells and a decrease in follicular B cells in CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST male and female mice when compared with control littermates (Figure 5). The mean fluorescence intensity was enhanced twofold in CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice when compared with controls. To confirm flow cytometry results, the splenic architecture was examined. The overall follicular structure and macrophage (CD169) distribution were not altered in CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice. However, the size of the MZ, as defined by IgM+ B cells, was enlarged, whereas IgM+ B cells in the white pulp (follicular B cells) were decreased in CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice compared with controls (Figure 5).

Table 3.

B-Cell Populations in the Bone Marrow of 2-Month–Old Notch2ΔPEST and RosaNotch1 Mice and Sex-Matched Littermate Controls

| Gate used | B220+ IgM− |

B220+CD19+CD117− |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19− CD117− pre–pro-B |

CD19+ CD117+ pro-B |

CD19+ CD117− pre-B |

IgM+ immature B |

|

| Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST | ||||

| Male | ||||

| Control | 30.5 ± 5.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 66.0 ± 6.1 | 74.6 ± 3.2 |

| Notch2ΔPEST | 27.2 ± 3.0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 69.7 ± 2.9 | 68.8 ± 4.1 |

| Female | ||||

| Control | 29.2 ± 3.7 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 67.3 ± 3.5 | 71.5 ± 1.6 |

| Notch2ΔPEST | 24.7 ± 4.4 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 72.9 ± 4.6 | 69.6 ± 5.5 |

| RosaNotch1 | ||||

| Male | ||||

| Control | 20.5 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 76.7 ± 1.0 | 66.1 ± 1.8 |

| RosaNotch1 | 26.0 ± 1.7∗ | 0.9 ± 0.1∗ | 72.9 ± 3.4 | 67.3 ± 1.0 |

| Female | ||||

| Control | 26.1 ± 2.3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 69.7 ± 4.5 | 67.3 ± 1.2 |

| RosaNotch1 | 31.4 ± 6.0 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 67.5 ± 7.8 | 73.2 ± 4.0 |

Data are expressed as percentages within the indicated gates and represent means ± SD for three to four biological replicates.

Notch2ΔPEST, CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST; RosaNotch1, CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT.

P < 0.05 RosaNotch1 versus control mice by unpaired t-test.

Figure 5.

B-cell allocation in the spleen of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice. Flow cytometry of spleen cells from control and CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice. A: Representative dot plot of flow cytometry of spleen cells from 2-month–old CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST (Notch2ΔPEST) and Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN control male and female sex-matched littermates. Cells were stained with anti-CD21/35 and anti-CD23 antibodies. Frequency of CD21/35highCD23− marginal zone (MZ) B cells and CD21/35intCD23+ follicular B cells gated on B220+/IgM+ B-cell populations is shown. Values represent the percentage of MZ B cells and follicular B cells. B: Histogram of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the CD21/35 cell population from 2-month–old CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST and Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN control mice. C: Bar graph of MFI of CD21/35 cells for control Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN and CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice. D: Representative image of spleen follicles [white pulp (WP)] stained with anti-IgM surrounded by a CD169+ metallophilic macrophage ring, stained with anti-CD169 antibodies, separating the red pulp (RP) and defining the MZ. The presence of nucleated cells was verified by DAPI staining (not shown). Data are expressed as means ± SD (A and C). n = 3 to 4 biological replicates (A); n = 4 biological replicates (C). ∗P < 0.05 versus control.

Induction of the NOTCH1-NICD in CD19 B-Cell Phenocopies CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST Mice

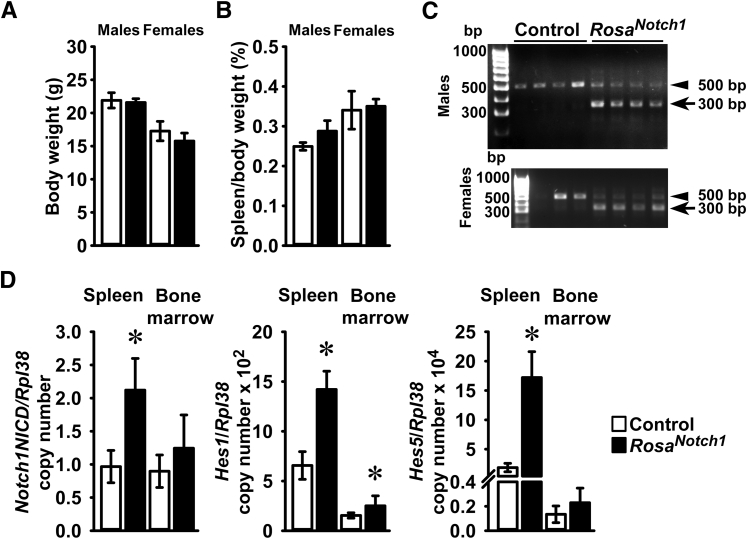

To determine whether the effect on MZ B-cell allocation was specific to Notch2, the conditional activation of Notch1 was induced in B cells. Homozygous RosaNotch1 mice were mated with CD19Cre/WT mice. In control experiments, flow cytometry of spleen cells from CD19Cre/WT or RosaNotch1 mice demonstrated no differences in B-cell populations when compared with wild-type littermates (data not shown). The general appearance, weight, and relative spleen size of CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice were not different from those of controls (Figure 6), and Cre-mediated recombination of loxP sites flanking the STOP cassette was documented in spleen genomic DNA (Figure 6). Basal Hes5 mRNA levels were detectable in control RosaNotch1 mice, whereas they were not detectable in either wild-type (Figure 2) or Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN control mice (Figure 4). Although there is no immediate explanation for this difference, it may be related to differences in colonies or the genetic manipulation of the Rosa26 locus, resulting in a modest level of basal Notch activation in the spleen. Notch1-NICD, Hes1, and Hes5 mRNA levels were increased in splenocytes from CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice when compared with control RosaNotch1/WT littermates, confirming induction of Notch signaling in the spleen (Figure 6). In accordance with the modest Cre expression in the bone marrow, minimal evidence of Notch activation was noted in this compartment.

Figure 6.

General appearance of CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice and Notch signaling in the spleen and bone marrow. Weight, spleen weight, documentation of Notch1 activation, and expression of Notch1 target genes in control and CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice. A: Body weight. B: Ratio of spleen/body weight. C: DNA was extracted from spleens of 2-month–old CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT and control RosaNotch1/WT male and female mice, and excision of the STOP was demonstrated by gel electrophoresis of PCR products obtained with primers specific for the RosaNotch1 allele. The arrowheads and arrows indicate the positions of the 500- and 300-bp amplicons, respectively, obtained from the intact or recombined RosaNotch1 alleles. D: Total RNA was extracted from spleen or bone marrow cells of 2-month–old CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT and control RosaNotch1/WT littermates, and gene expression was measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Notch1NICD, Hes1, and Hes5 mRNA copy numbers corrected for Rpl38 expression are shown. Two technical replicates were used for each real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A, B, and D). n = 7 control and n = 5 CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT for male mice; n = 6 control and n = 3 CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT for female mice (A and B); n = 8 control and n = 5 CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT biological replicates for spleen; n = 8 control and n = 7 CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT biological replicates for bone marrow samples (D). ∗P < 0.05 versus control (t-test).

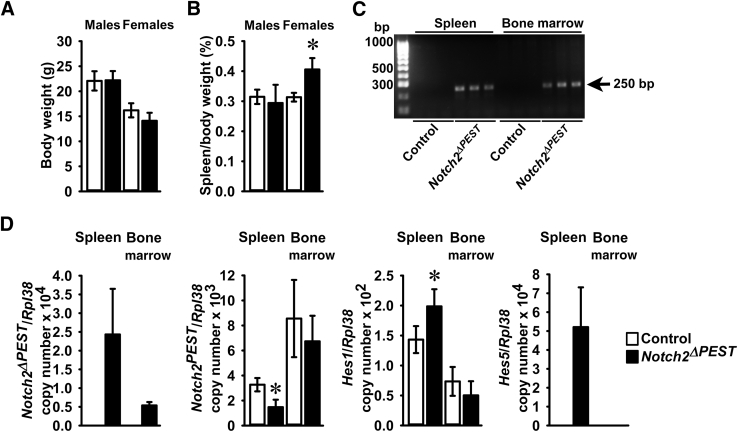

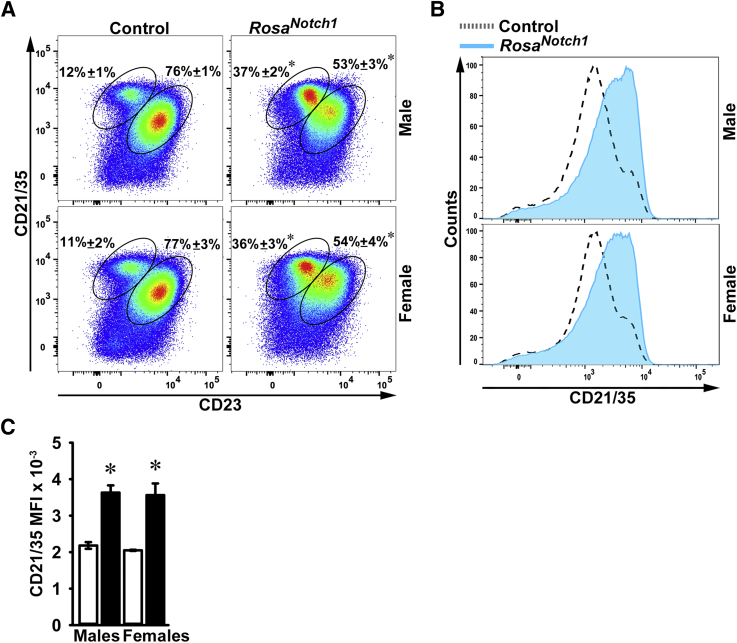

Flow cytometry of B cells isolated from the bone marrow demonstrated modest differences between CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT and control mice in the frequency of pre–pro-B and pro-B cells in the bone marrow (Table 3). Flow cytometry of spleen cells revealed a threefold increase in MZ B cells and a decrease in follicular B cells in male and female mice when compared with littermate controls (Figure 7). The CD21/35 mean fluorescence intensity was enhanced 1.7- to 2-fold in CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice. These findings demonstrate that activation of Notch1 in CD19-expressing cells recapitulates the splenic phenotype of the Notch2tm1.1ECan and CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice and indicates that activation of Notch signaling in CD19+ B cells, irrespective of the identity of the receptor, alters B-cell allocation in the spleen.

Figure 7.

B-cell allocation in the spleen of CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice. Flow cytometry of spleen cells from control and CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice. A: Representative dot plot of flow cytometry of spleen cells from 2-month–old CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT and control male and female sex-matched littermates. Cells were stained with anti-CD21/35 and anti-CD23 antibodies. Frequency of CD21/35highCD23− marginal zone (MZ) B cells and CD21/35intCD23+ follicular B cells gated on B220+/IgM+ B-cell populations is shown. Values represent the percentage of MZ B cells and follicular B cells. B: Histogram of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the CD21/35 cell population from 2-month–old CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT and RosaNotch1/WT control mice. C: Bar graph of MFI of the CD21/35 cells for control (white bars) and CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT (black bars) mice. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A and C). n = 3 to 4 biological replicates (A and C). ∗P < 0.05 versus control (t-test).

Prolonged Activation of Notch in the B-Cell Lineage Does Not Cause a Skeletal Phenotype

To establish whether the osteopenic phenotype previously reported in global Notch2tm1.1ECan and Notch2ΔPEST/WT germline mutants is secondary to the effect of Notch2 in B cells, the skeletal phenotype of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice and Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN littermate controls was determined.26, 35 In preliminary studies, CD19Cre/WT, Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN, and RosaNotch1/WT mice do not have a skeletal phenotype, as determined by μCT of distal femurs, when compared with wild-type controls35, 40 (data not shown). Femoral architectural analysis by μCT of male and female 2-month–old CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice revealed no differences when compared with wild-type sex-matched littermate controls (Table 4).

Table 4.

Femoral Microarchitecture Assessed by μCT of 2-Month–Old Notch2ΔPEST Mice and Sex-Matched Littermate Controls

| Variable | Males |

Females |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 5) | Notch2ΔPEST (n = 7) | Control (n = 7) | Notch2ΔPEST (n = 6) | |

| Distal femur trabecular bone | ||||

| Bone/total volume, % | 12.6 ± 1.2 | 14.9 ± 2.3 | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 6.2 ± 2.4 |

| Trabecular separation, μm | 153 ± 11 | 143 ± 17 | 226 ± 9 | 214 ± 27 |

| Trabecular no., 1/mm | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.6 |

| Trabecular thickness, μm | 33 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 28 ± 3 |

| Connectivity density, 1/mm3 | 487 ± 96 | 641 ± 151 | 134 ± 46 | 187 ± 103 |

| Structure-model index | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| Density of material, mg HA/cm3 | 1053 ± 10 | 1047 ± 21 | 1039 ± 16 | 1027 ± 18 |

| Femoral midshaft cortical bone | ||||

| Bone/total volume, % | 91.4 ± 0.8 | 91.4 ± 1.4 | 86.1 ± 1.3 | 86.6 ± 2.2 |

| Porosity, % | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 8.3 ± 1.4 | 13.9 ± 1.3 | 13.4 ± 2.2 |

| Cortical thickness, μm | 178 ± 6 | 177 ± 13 | 130 ± 7 | 130 ± 17 |

| Total area, mm2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| Bone area, mm2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Periosteal perimeter, μm | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.2 |

| Endocortical perimeter, mm | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2 |

| Density of material, mg HA/cm3 | 1138 ± 37 | 1131 ± 33 | 1136 ± 22 | 1122 ± 2.5 |

μCT was performed at the femoral distal end for trabecular or midshaft for cortical bone. Data are expressed as means ± SD of biological replicates.

μCT, microcomputed tomography; HA, hydroxyapatite; Notch2ΔPEST, CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST.

To verify that Notch activation in B cells does not alter skeletal homeostasis, the phenotype of CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT mice was examined. Analysis of the distal femur by μCT revealed that the cancellous and cortical bone of CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT male and female mice was not different from that of RosaNotch1/WT littermate sex-matched controls (Table 5). These results demonstrate that neither the activation of Notch1 nor the activation of Notch2 in CD19-expressing cells results in a skeletal phenotype.

Table 5.

Femoral Microarchitecture Assessed by μCT of 2-Month–Old RosaNotch1 Mice and Sex-Matched Littermate Controls

| Variables | Males |

Females |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 7) | RosaNotch1 (n = 5) | Control (n = 6) | RosaNotch1 (n = 3) | |

| Distal femur trabecular bone | ||||

| Bone/total volume, % | 9.3 ± 4.4 | 7.4 ± 3.0 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 5.0 ± 0.6 |

| Trabecular separation, μm | 188 ± 28 | 199 ± 21 | 228 ± 17 | 227 ± 12 |

| Trabecular no., 1/mm | 5.4 ± 0.8 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

| Trabecular thickness, μm | 33 ± 5 | 32 ± 4 | 30 ± 2 | 28 ± 1 |

| Connectivity density, 1/mm3 | 274 ± 180 | 197 ± 138 | 109 ± 45 | 109 ± 33 |

| Structure-model index | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

| Density of material, mg HA/cm3 | 1023 ± 16 | 1017 ± 16 | 1009 ± 17 | 1014 ± 13 |

| Femoral midshaft cortical bone | ||||

| Bone/total volume, % | 86.6 ± 2.7 | 85.7 ± 2.6 | 86.6 ± 2.9 | 85.6 ± 1.2 |

| Porosity, % | 13.4 ± 2.7 | 14.3 ± 2.6 | 13.4 ± 2.9 | 14.4 ± 1.2 |

| Cortical thickness, μm | 148 ± 20 | 138 ± 19 | 133 ± 17 | 130 ± 7 |

| Total area, mm2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| Bone area, mm2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Periosteal perimeter, μm | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.1 |

| Endocortical perimeter, mm | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| Density of material, mg HA/cm3 | 1137 ± 14 | 1132 ± 11 | 1158 ± 22 | 1141 ± 1.2 |

μCT was performed at the femoral distal end for trabecular or midshaft for cortical bone. Data are expressed as means ± SD of biological replicates.

μCT, microcomputed tomography; HA, hydroxyapatite; RosaNotch1, CD19Cre/WT;RosaNotch1/WT.

Changes in B-Cell Allocation in the Spleen Do Not Affect the Skeleton

To ensure that the effect of Notch2 on B-cell allocation in the spleen does not influence skeletal homeostasis, splenectomies or sham operations were performed in 1-month–old heterozygous Notch2tm1.1ECan global mutant male and female mice, known to have altered B-cell allocation in the spleen and to be osteopenic.26, 28 Notch2tm1.1ECan mice were obtained after the crossings of Notch2tm1.1ECan heterozygous mice with wild-type mice, all in a C57BL/6J genetic background. Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant mice were compared with sex-matched littermate controls at 2 months of age. μCT of the distal femur confirmed that 2-month–old Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant mice had a 40% to 50% decrease in trabecular bone volume associated with decreased trabecular number and decreased cortical bone area.26, 52 Splenectomy did not reverse the cancellous or cortical bone osteopenic phenotype of Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant mice. As a result, cancellous bone volume/total volume and cortical bone area were lower in Notch2tm1.1ECan mice, whether they were sham operated or splenectomized (Table 6). These results confirm that the Notch2-dependent alterations in cells of the spleen are not responsible for the skeletal manifestations of Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant mice.

Table 6.

Femoral Microarchitecture Assessed by μCT of 2-Month–Old Notch2tm1.1ECan Mutant Mice and Sex-Matched Control Littermates Subjected to Splenectomies or Sham Interventions

| Males | Sham |

Splenectomy |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 6) | Notch2tm1.1ECan (n = 5) | Control (n = 7) | Notch2tm1.1ECan (n = 4) | |

| Distal femur trabecular bone | ||||

| Bone/total volume, % | 8.8 ± 2.7 | 5.2 ± 3.2 | 11.1 ± 3.5 | 4.0 ± 2.9∗ |

| Trabecular separation, μm | 207 ± 11 | 281 ± 39∗ | 201 ± 36 | 333 ± 79∗ |

| Trabecular no., 1/mm | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.6∗ | 5.1 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.8∗ |

| Trabecular thickness, μm | 39 ± 6 | 35 ± 7 | 44 ± 5 | 32 ± 6∗ |

| Connectivity density, 1/mm3 | 215 ± 71 | 123 ± 105 | 269 ± 83 | 85 ± 76∗ |

| Structure-model index | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.5∗ |

| Density of material, mg HA/cm3 | 855 ± 18 | 819 ± 26∗ | 867 ± 25 | 800 ± 29∗ |

| Femoral midshaft cortical bone | ||||

| Bone/total volume, % | 87.5 ± 1.3 | 83.9 ± 4.6∗ | 87.8 ± 1.6 | 83.8 ± 2.6∗ |

| Porosity, % | 12.5 ± 1.3 | 16.1 ± 4.6∗ | 12.2 ± 1.6 | 16.2 ± 2.6∗ |

| Cortical thickness, μm | 148 ± 13 | 119 ± 21∗ | 152 ± 11 | 116 ± 13∗ |

| Total area, mm2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2∗ |

| Bone area, mm2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1∗ | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1∗ |

| Periosteal perimeter, mm | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.3∗ |

| Endocortical perimeter, mm | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.3 |

| Density of material, mg HA/cm3 | 1119 ± 16 | 1093 ± 35 | 1123 ± 21 | 1083 ± 22∗ |

| Females | Sham |

Splenectomy |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 5) | Notch2tm1.1ECan (n = 5) | Control (n = 4) | Notch2tm1.1ECan (n = 6) | |

| Distal femur trabecular bone | ||||

| Bone/total volume, % | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.1∗ | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 1.6∗ |

| Trabecular separation, μm | 261 ± 20 | 355 ± 72 | 272 ± 57 | 402 ± 109 |

| Trabecular no., 1/mm | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.6∗ | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.7∗ |

| Trabecular thickness, μm | 35 ± 2 | 29 ± 3∗ | 33 ± 1 | 30 ± 3 |

| Connectivity density, 1/mm3 | 158 ± 56 | 57 ± 37∗ | 118 ± 54 | 69 ± 44 |

| Structure-model index | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| Density of material, mg HA/cm3 | 843 ± 16 | 825 ± 7 | 844 ± 16 | 813 ± 24∗ |

| Femoral midshaft cortical bone | ||||

| Bone/total volume, % | 87.1 ± 0.8 | 84.1 ± 3.0 | 85.7 ± 2.2 | 79.9 ± 7.0 |

| Porosity, % | 12.9 ± 0.8 | 15.9 ± 3.0 | 14.3 ± 2.2 | 20.1 ± 7.0 |

| Cortical thickness, μm | 136 ± 10 | 119 ± 18 | 128 ± 14 | 101 ± 23∗ |

| Total area, mm2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1∗ | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| Bone area, mm2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1∗ | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1∗ |

| Periosteal perimeter, mm | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.2∗ | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.2 |

| Endocortical perimeter, mm | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.3 |

| Density of material, mg HA/cm3 | 1123 ± 9 | 1099 ± 47 | 1111 ± 20 | 1057 ± 43∗ |

Notch2tm1.1ECan and control sex-matched littermates were subjected to splenectomies or sham interventions at 1 month of age and sacrificed 1 month later for analysis. μCT was performed at the femoral distal end for trabecular or midshaft for cortical bone. Data are expressed as means ± SD of biological replicates.

μCT, microcomputed tomography; HA, hydroxyapatite.

P < 0.05 versus control mice (two-way analysis of variance with Holm-Šídák post-hoc analysis).

Discussion

In this study, the contribution of CD19+ B cells to the spleen and bone phenotypes of Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant mice was explored by the conditional introduction of the HCS genetic defect in the B-cell lineage. The mutations associated with the disease occur within exon 34 of NOTCH2, and the conditional insertion of a premature stop codon in the homologous region of the murine Notch2 locus was achieved by the generation of a COIN allele, as reported previously.35 This approach allows genetic alterations to be introduced within coding exons without disrupting the expression or function of the targeted locus before the inversion of the COIN module, a goal that cannot be accomplished with a traditional Cre-loxP strategy. The Notch2ΔPEST mutants generated by germline inversion of the COIN allele expressed the Notch2ΔPEST transcript and phenocopied the spleen alterations present in global Notch2tm1.1ECan mutants.28 This confirms that the generalized expression of a Notch2 mutant lacking the PEST domain causes an MZ B-cell phenotype.

The present study demonstrates that either the induction of a Notch2 gain-of-function mutation or activation of Notch1 signaling in CD19-expressing cells alters B-cell allocation in the MZ of the spleen, with an increase in MZ B cells and a reduction in follicular B cells. A modest and unexplained decrease in MZ B cells was observed in Notch2[ΔPEST]COIN/[ΔPEST]COIN mice, before recombination, when compared with wild-type littermates. This should not influence the interpretation of the results in view of the magnitude (sixfold to sevenfold) of the increase in MZ B cells in CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice when compared with controls and the fact that they have an analogous phenotype to that of global Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant and of germline Notch2ΔPEST mice.28 There were no changes in the distribution of early B cells in the bone marrow after the induction of either Notch1 or Notch2, suggesting that Notch primarily affects the allocation of mature B cells in the spleen. Although lower expression of Cre recombinase in the bone marrow than in the spleen of CD19Cre/WT mice, and as a consequence a lower induction of Notch target genes, was confirmed, this does not seem to be the only reason for the lack of an effect on B-cell population in the bone marrow of mice with enhanced Notch signaling. In fact, global Notch2tm1.1ECan mice with a gain-of-Notch2 function exhibit an MZ spleen phenotype, but no changes in the bone marrow B-cell population. The results suggest that Notch affects the allocation of mature B cells, but not the early stages of B-cell differentiation. This is in agreement with previous work demonstrating that Notch2 is preferentially expressed in mature B cells and Notch2 haploinsufficiency; the selective inactivation of Notch2, Adam10, or Rbpjκ in CD19-expressing cells results in a severe reduction in MZ mature B cells.13, 14, 15, 53 Our studies also confirm work showing that the NOTCH2-NICD expression in CD19 cells drives B cells toward the MZ B-cell compartment at the expense of the follicular B cells.17

It is of interest that the spleen phenotype of CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice was reproduced after the forced activation of Notch1 in CD19-expressing cells. These effects are possibly explained by similarities between the Notch1 and Notch2 intracellular domains and by the fact that under selected conditions, the intracellular domains of both receptors are functionally equivalent.54, 55 However, this does not mean that Notch1 and Notch2 have redundant functions, because differences related to their pattern of expression and the distinct nature of their interactions with RBPJκ lead to distinct cellular responses.7

Although subjects with HCS are not known to have alterations in B-cell allocation, a recent report documents splenomegaly in an affected individual.18 It is of interest that subjects with Alagille syndrome associated with JAG1 mutations do not have abnormalities in B-cell populations, whereas individuals with Alagille syndrome associated with NOTCH2 haploinsufficiency display a marked reduction in IgM+IgD+CD27+ MZ B cells, arguing for a role of Notch2 in B-cell allocation in humans.16 Humans have a less well-developed MZ of the spleen than rodents, and the organization of the marginal and follicular zone in the human spleen differs from that in the mouse.56

The conditional HCS mutant model described in this study reaffirmed that Notch2 increases the transcript levels of Hes1 and Hes5 in the spleen, confirming that Notch2 activates RBPJκ-mediated Notch signaling in this organ. The increase in mRNA levels for these Notch target genes reflects activation of the Notch canonical pathway but does not imply that HES proteins mediate the effect of Notch2 in the spleen.

Although the selective introduction of the HCS mutation in CD19 B cells caused an MZ B-cell phenotype, it did not cause cancellous or cortical bone osteopenia. This would indicate that the roles of Notch2 in B-cell allocation and skeletal homeostasis are not interdependent. The observations are consistent with recent work demonstrating that the skeletal phenotype of Notch2tm1.1ECan mutants is largely secondary to a direct effect of Notch2 in osteoblasts and, to a lesser extent, in osteoclasts.35, 52 These results indicate that the activation of Notch2 in B cells in vivo has no skeletal consequences and that the effect of Notch2 on bone resorption is mostly secondary to its actions on cells of the osteoblast and osteoclast lineage.

Previous work has demonstrated that the expression of Tnfsf11 (encoding for RANKL) in CD19-expressing cells is responsible for the osteopenia that occurs after ovariectomy.34 However, Tnfsf11 mRNA was not detected in CD19+ spleen cells of wild-type or Notch2tm1.1ECan mice, and Tnfsf11 transcripts were not induced in spleens of Notch2ΔPEST mice, possibly explaining the absence of a skeletal phenotype in CD19Cre/WT;Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST mice. Our previous work demonstrated that Notch2ΔPEST/ΔPEST osteoblasts express increased levels of Tnfsf11 mRNA, suggesting that osteoblast-derived RANKL is responsible for the enhanced bone resorption in Notch2tm1.1ECan mutant mice.35, 52, 57 Similarly, a subject with HCS and severe osteoporosis was reported to present with elevated levels of RANKL in the serum.18

In conclusion, introduction of a Notch2 mouse mutant lacking the PEST domain in CD19-expressing cells determines the B-cell reallocation in the spleen, but this does not alter skeletal homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emmanuelle Six for Dll1 cDNA, Jeffrey S. Nye for Notch1 cDNA, Ryoichiro Kageyama for Hes5 cDNA, Yasuaki Shirayoshi for Notch4 cDNA, Tabitha Eller, David Bridgewater, and Quynh-Mai Pham for technical support, and Mary Yurczak for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease grant DK045227 (E.C.) and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grants AR063049 (E.C.) and AR068160 (E.C.).

J.Y. and S.Z. contributed equally to this work; A.S. and E.C. contributed equally as senior/corresponding authors to this work.

Disclosures: C.S. and A.N.E. receive stock options from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.02.010.

Contributor Information

Archana Sanjay, Email: asanjay@uchc.edu.

Ernesto Canalis, Email: canalis@uchc.edu.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Schroeter E.H., Kisslinger J.A., Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zanotti S., Canalis E. Notch and the skeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:886–896. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01285-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovall R.A. More complicated than it looks: assembly of Notch pathway transcription complexes. Oncogene. 2008;27:5099–5109. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nam Y., Sliz P., Song L., Aster J.C., Blacklow S.C. Structural basis for cooperativity in recruitment of MAML coactivators to Notch transcription complexes. Cell. 2006;124:973–983. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson J.J., Kovall R.A. Crystal structure of the CSL-Notch-Mastermind ternary complex bound to DNA. Cell. 2006;124:985–996. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iso T., Kedes L., Hamamori Y. HES and HERP families: multiple effectors of the Notch signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:237–255. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan Z., Friedmann D.R., Vanderwielen B.D., Collins K.J., Kovall R.A. Characterization of CSL (CBF-1, Su(H), Lag-1) mutants reveals differences in signaling mediated by Notch1 and Notch2. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34904–34916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.403287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radtke F., Wilson A., Stark G., Bauer M., van Meerwijk J., MacDonald H.R., Aguet M. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10:547–558. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pear W.S., Aster J.C. T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma: a human cancer commonly associated with aberrant NOTCH1 signaling. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11:426–433. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000143965.90813.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S.Y., Kumano K., Nakazaki K., Sanada M., Matsumoto A., Yamamoto G., Nannya Y., Suzuki R., Ota S., Ota Y., Izutsu K., Sakata-Yanagimoto M., Hangaishi A., Yagita H., Fukayama M., Seto M., Kurokawa M., Ogawa S., Chiba S. Gain-of-function mutations and copy number increases of Notch2 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:920–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossi D., Trifonov V., Fangazio M., Bruscaggin A., Rasi S., Spina V. The coding genome of splenic marginal zone lymphoma: activation of NOTCH2 and other pathways regulating marginal zone development. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1537–1551. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witt C.M., Hurez V., Swindle C.S., Hamada Y., Klug C.A. Activated Notch2 potentiates CD8 lineage maturation and promotes the selective development of B1 B cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8637–8650. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8637-8650.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanigaki K., Han H., Yamamoto N., Tashiro K., Ikegawa M., Kuroda K., Suzuki A., Nakano T., Honjo T. Notch-RBP-J signaling is involved in cell fate determination of marginal zone B cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:443–450. doi: 10.1038/ni793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito T., Chiba S., Ichikawa M., Kunisato A., Asai T., Shimizu K., Yamaguchi T., Yamamoto G., Seo S., Kumano K., Nakagami-Yamaguchi E., Hamada Y., Aizawa S., Hirai H. Notch2 is preferentially expressed in mature B cells and indispensable for marginal zone B lineage development. Immunity. 2003;18:675–685. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witt C.M., Won W.J., Hurez V., Klug C.A. Notch2 haploinsufficiency results in diminished B1 B cells and a severe reduction in marginal zone B cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2783–2788. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Descatoire M., Weller S., Irtan S., Sarnacki S., Feuillard J., Storck S., Guiochon-Mantel A., Bouligand J., Morali A., Cohen J., Jacquemin E., Iascone M., Bole-Feysot C., Cagnard N., Weill J.C., Reynaud C.A. Identification of a human splenic marginal zone B cell precursor with NOTCH2-dependent differentiation properties. J Exp Med. 2014;211:987–1000. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hampel F., Ehrenberg S., Hojer C., Draeseke A., Marschall-Schroter G., Kuhn R., Mack B., Gires O., Vahl C.J., Schmidt-Supprian M., Strobl L.J., Zimber-Strobl U. CD19-independent instruction of murine marginal zone B-cell development by constitutive Notch2 signaling. Blood. 2011;118:6321–6331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adami G., Rossini M., Gatti D., Orsolini G., Idolazzi L., Viapiana O., Scarpa A., Canalis E. Hajdu Cheney syndrome: report of a novel NOTCH2 mutation and treatment with denosumab. Bone. 2016;92:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canalis E., Zanotti S. Hajdu-Cheney syndrome: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:200. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0200-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canalis E., Zanotti S. Hajdu-Cheney syndrome, a disease associated with NOTCH2 mutations. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2016;14:126–131. doi: 10.1007/s11914-016-0311-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray M.J., Kim C.A., Bertola D.R., Arantes P.R., Stewart H., Simpson M.A., Irving M.D., Robertson S.P. Serpentine fibula polycystic kidney syndrome is part of the phenotypic spectrum of Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:122–124. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isidor B., Lindenbaum P., Pichon O., Bezieau S., Dina C., Jacquemont S., Martin-Coignard D., Thauvin-Robinet C., Le M.M., Mandel J.L., David A., Faivre L., Cormier-Daire V., Redon R., Le C.C. Truncating mutations in the last exon of NOTCH2 cause a rare skeletal disorder with osteoporosis. Nat Genet. 2011;43:306–308. doi: 10.1038/ng.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majewski J., Schwartzentruber J.A., Caqueret A., Patry L., Marcadier J., Fryns J.P., Boycott K.M., Ste-Marie L.G., McKiernan F.E., Marik I., Van E.H., Michaud J.L., Samuels M.E. Mutations in NOTCH2 in families with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:1114–1117. doi: 10.1002/humu.21546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson M.A., Irving M.D., Asilmaz E., Gray M.J., Dafou D., Elmslie F.V., Mansour S., Holder S.E., Brain C.E., Burton B.K., Kim K.H., Pauli R.M., Aftimos S., Stewart H., Kim C.A., Holder-Espinasse M., Robertson S.P., Drake W.M., Trembath R.C. Mutations in NOTCH2 cause Hajdu-Cheney syndrome, a disorder of severe and progressive bone loss. Nat Genet. 2011;43:303–305. doi: 10.1038/ng.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao W., Petit E., Gafni R.I., Collins M.T., Robey P.G., Seton M., Miller K.K., Mannstadt M. Mutations in NOTCH2 in patients with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2275–2281. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2298-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canalis E., Schilling L., Yee S.P., Lee S.K., Zanotti S. Hajdu Cheney mouse mutants exhibit osteopenia, increased osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:1538–1551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.685453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukushima H., Shimizu K., Watahiki A., Hoshikawa S., Kosho T., Oba D., Sakano S., Arakaki M., Yamada A., Nagashima K., Okabe K., Fukumoto S., Jimi E., Bigas A., Nakayama K.I., Nakayama K., Aoki Y., Wei W., Inuzuka H. NOTCH2 Hajdu-Cheney mutations escape SCF(FBW7)-dependent proteolysis to promote osteoporosis. Mol Cell. 2017;68:645–658.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J., Zanotti S., Walia B., Jellison E., Sanjay A., Canalis E. The Hajdu Cheney mutation is a determinant of B-cell allocation of the splenic marginal zone. Am J Pathol. 2018;188:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horowitz M.C., Fretz J.A., Lorenzo J.A. How B cells influence bone biology in health and disease. Bone. 2010;47:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Toraldo G., Li A., Yang X., Zhang H., Qian W.P., Weitzmann M.N. B cells and T cells are critical for the preservation of bone homeostasis and attainment of peak bone mass in vivo. Blood. 2007;109:3839–3848. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manilay J.O., Zouali M. Tight relationships between B lymphocytes and the skeletal system. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y., Terauchi M., Vikulina T., Roser-Page S., Weitzmann M.N. B cell production of both OPG and RANKL is significantly increased in aged mice. Open Bone J. 2014;6:8–17. doi: 10.2174/1876525401406010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meednu N., Zhang H., Owen T., Sun W., Wang V., Cistrone C., Rangel-Moreno J., Xing L., Anolik J.H. Production of RANKL by memory B cells: a link between B cells and bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:805–816. doi: 10.1002/art.39489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onal M., Xiong J., Chen X., Thostenson J.D., Almeida M., Manolagas S.C., O'Brien C.A. Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL) protein expression by B lymphocytes contributes to ovariectomy-induced bone loss. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29851–29860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.377945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanotti S., Yu J., Sanjay A., Schilling L., Schoenherr C., Economides A.N., Canalis E. Sustained Notch2 signaling in osteoblasts, but not in osteoclasts, is linked to osteopenia in a mouse model of Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:12232–12244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.786129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murtaugh L.C., Stanger B.Z., Kwan K.M., Melton D.A. Notch signaling controls multiple steps of pancreatic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14920–14925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436557100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Economides A.N., Frendewey D., Yang P., Dominguez M.G., Dore A.T., Lobov I.B., Persaud T., Rojas J., McClain J., Lengyel P., Droguett G., Chernomorsky R., Stevens S., Auerbach W., DeChiara T.M., Pouyemirou W., Cruz J.M., Jr., Feeley K., Mellis I.A., Yasenchack J., Hatsell S.J., Xie L., Latres E., Huang L., Zhang Y., Pefanis E., Skokos D., Deckelbaum R.A., Croll S.D., Davis S., Valenzuela D.M., Gale N.W., Murphy A.J., Yancopoulos G.D. Conditionals by inversion provide a universal method for the generation of conditional alleles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E3179–E3188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217812110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang S.H., Silva F.J., Tsark W.M., Mann J.R. A Cre/loxP-deleter transgenic line in mouse strain 129S1/SvImJ. Genesis. 2002;32:199–202. doi: 10.1002/gene.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rickert R.C., Roes J., Rajewsky K. B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1317–1318. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canalis E., Parker K., Feng J.Q., Zanotti S. Osteoblast lineage-specific effects of notch activation in the skeleton. Endocrinology. 2013;154:623–634. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nazarenko I., Pires R., Lowe B., Obaidy M., Rashtchian A. Effect of primary and secondary structure of oligodeoxyribonucleotides on the fluorescent properties of conjugated dyes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2089–2195. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nazarenko I., Lowe B., Darfler M., Ikonomi P., Schuster D., Rashtchian A. Multiplex quantitative PCR using self-quenched primers labeled with a single fluorophore. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e37. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Six E.M., Ndiaye D., Sauer G., Laabi Y., Athman R., Cumano A., Brou C., Israel A., Logeat F. The notch ligand Delta1 recruits Dlg1 at cell-cell contacts and regulates cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55818–55826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nye J.S., Kopan R., Axel R. An activated Notch suppresses neurogenesis and myogenesis but not gliogenesis in mammalian cells. Development. 1994;120:2421–2430. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirayoshi Y., Yuasa Y., Suzuki T., Sugaya K., Kawase E., Ikemura T., Nakatsuji N. Proto-oncogene of int-3, a mouse Notch homologue, is expressed in endothelial cells during early embryogenesis. Genes Cells. 1997;2:213–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.d01-310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akazawa C., Sasai Y., Nakanishi S., Kageyama R. Molecular characterization of a rat negative regulator with a basic helix-loop-helix structure predominantly expressed in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21879–21885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gibson D.G., Young L., Chuang R.Y., Venter J.C., Hutchison C.A., 3rd, Smith H.O. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kouadjo K.E., Nishida Y., Cadrin-Girard J.F., Yoshioka M., St-Amand J. Housekeeping and tissue-specific genes in mouse tissues. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bouxsein M.L., Boyd S.K., Christiansen B.A., Guldberg R.E., Jepsen K.J., Muller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glatt V., Canalis E., Stadmeyer L., Bouxsein M.L. Age-related changes in trabecular architecture differ in female and male C57BL/6J mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1197–1207. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwenk F., Sauer B., Kukoc N., Hoess R., Muller W., Kocks C., Kuhn R., Rajewsky K. Generation of Cre recombinase-specific monoclonal antibodies, able to characterize the pattern of Cre expression in cre-transgenic mouse strains. J Immunol Methods. 1997;207:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Canalis E., Sanjay A., Yu J., Zanotti S. An antibody to Notch2 reverses the osteopenic phenotype of Hajdu-Cheney mutant male mice. Endocrinology. 2017;158:730–742. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibb D.R., El Shikh M., Kang D.J., Rowe W.J., El Sayed R., Cichy J., Yagita H., Tew J.G., Dempsey P.J., Crawford H.C., Conrad D.H. ADAM10 is essential for Notch2-dependent marginal zone B cell development and CD23 cleavage in vivo. J Exp Med. 2010;207:623–635. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zanotti S., Canalis E. Notch signaling and the skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2016;37:223–253. doi: 10.1210/er.2016-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Z., Brunskill E., Varnum-Finney B., Zhang C., Zhang A., Jay P.Y., Bernstein I., Morimoto M., Kopan R. The intracellular domains of Notch1 and Notch2 are functionally equivalent during development and carcinogenesis. Development. 2015;142:2452–2463. doi: 10.1242/dev.125492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zouali M., Richard Y. Marginal zone B-cells, a gatekeeper of innate immunity. Front Immunol. 2011;2:63. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vollersen N., Hermans-Borgmeyer I., Cornils K., Fehse B., Rolvien T., Triviai I., Jeschke A., Oheim R., Amling M., Schinke T., Yorgan T.A. High bone turnover in mice carrying a pathogenic Notch2-mutation causing Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:70–83. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.