ABSTRACT

The two-partner secretion system ExlBA, expressed by strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa belonging to the PA7 group, induces hemorrhage in lungs due to disruption of host cellular membranes. Here we demonstrate that the exlBA genes are controlled by a pathway consisting of cAMP and the virulence factor regulator (Vfr). Upon interaction with cAMP, Vfr binds directly to the exlBA promoter with high affinity (equilibrium binding constant [Keq] of ≈2.5 nM). The exlB and exlA expression was diminished in the Vfr-negative mutant and upregulated with increased intracellular cAMP levels. The Vfr binding sequence in the exlBA promoter was mutated in situ, resulting in reduced cytotoxicity of the mutant, showing that Vfr is required for the exlBA expression during intoxication of epithelial cells. Vfr also regulates function of type 4 pili previously shown to facilitate ExlA activity on epithelial cells, which indicates that the cAMP/Vfr pathway coordinates these two factors needed for full cytotoxicity. As in most P. aeruginosa strains, the adenylate cyclase CyaB is the main provider of cAMP for Vfr regulation during both in vitro growth and eukaryotic cell infection. We discovered that the absence of functional Vfr in the reference strain PA7 is caused by a frameshift in the gene and accounts for its reduced cytotoxicity, revealing the conservation of ExlBA control by the CyaB-cAMP/Vfr pathway in P. aeruginosa taxonomic outliers.

IMPORTANCE The human opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa provokes severe acute and chronic human infections associated with defined sets of virulence factors. The main virulence determinant of P. aeruginosa taxonomic outliers is exolysin, a membrane-disrupting pore-forming toxin belonging to the two-partner secretion system ExlBA. In this work, we demonstrate that the conserved CyaB-cAMP/Vfr pathway controls cytotoxicity of outlier clinical strains through direct transcriptional activation of the exlBA operon. Therefore, despite the fact that the type III secretion system and exolysin are mutually exclusive in classical and outlier strains, respectively, these two major virulence determinants share similarities in their mechanisms of regulation.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Vfr, cAMP, gene regulation, TPS, exolysin, PA7 group, virulence, cyclic AMP

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial virulence factors are tightly regulated by complex regulatory networks integrating multiple stimuli to ensure their synthesis only when required (1). Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a major inhabitant of various environmental reservoirs, is also an important human opportunistic pathogen and, consequently, a frequently used model for studying virulence gene regulation. Its exceptional regulatory complexity was suggested from the 6.3-Mb genome of the reference strain PAO1, containing 5,570 genes with roughly 12% of them devoted to regulation (2–4). Additionally, more than 500 putative noncoding RNAs carrying potential regulatory functions were found in different strains (5–7) further increasing the complexity of regulatory networks used by this versatile microorganism. Quorum sensing (QS [with four interconnected systems: Las, Rhl, PQS, and IQS]), the two-component regulatory systems (comprising around 60 of both histidine kinases and response regulators and 3 Hpt proteins), the Gac/Rsm system (with regulatory RNAs RsmY and RsmZ negatively controlling the activity of the posttranscriptional regulator RsmA), and the 2 second messengers (cyclic AMP [cAMP] and cyclic di-GMP [c-di-GMP]) (1, 8–10) are among the well-characterized networks controlling virulence. These regulatory pathways govern the reciprocal expression of the virulence factors, depending on the P. aeruginosa “lifestyle.” During planktonic growth, the bacteria express factors involved in acute virulence, such as pili, flagella, and toxins, and most of these factors are under the positive control of QS and cAMP, an allosteric activator of the virulence factor regulator, Vfr (11). In contrast, other factors like exopolysaccharides and adhesins are synthesized under growth in a structured and multicellular community called “biofilm.” A high c-di-GMP level is commonly associated with this mode of life in several pathogenic bacteria, even if only a few direct targets have been identified up to now (12, 13). These regulatory circuits were mainly studied in most common laboratory strains (PAO1, PAK, and PA14), and they are encoded within their core genome. However, there are some strain variations that have been reported, such as strains with point mutations or deletions in key regulatory genes affecting their virulence. For instance, the defective genes mexS in PAK, ladS in PA14, and gacS in cystic fibrosis (CF) isolate CHA are responsible for overexpression of genes encoding the type 3 secretion system (T3SS), the major virulence factor of P. aeruginosa (14–16).

The existence of P. aeruginosa taxonomic outliers with the fully sequenced PA7 strain as the representative was recently reported (17–22). They constitute one of the three major groups of P. aeruginosa strains defined from phylogenetic analysis of core genome sequences (23). The PA7 strain exhibits low sequence identity of its core genome to the “classical” strains PAO1 (group 1) and PA14 (group 2) (95% instead of the >99% usually found) and possesses numerous specific regions of genome plasticity (RGPs) encoding notably a third specific type 2 secretion system, Txc (17, 24). An unexpected but important feature of PA7 is the absence of the toxA gene, as well as the absence of the determinants for the entire T3SS apparatus and all T3SS-exported toxins (17). While characterizing the PA7-like strain CLJ1, isolated from a patient suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and hemorrhagic pneumonia, we discovered a new type 5 secretion system (T5SS) responsible for this strain's pathogenicity. This T5SS is composed of two proteins—ExlB and ExlA. ExlB is the outer membrane protein that facilitates the secretion of the pore-forming protein exolysin (ExlA) responsible for membrane permeabilization and cell death (19, 21, 25). Since 2010, approximately 30 additional PA7-like strains have been reported in publications, and some of these were studied in more detail. We analyzed the phenotypes of the majority of exlA+ PA7-like strains and their ability to produce ExlA. Interestingly, different levels of ExlA secretion were observed among these strains leading to variations in the extent of cytotoxicity and pathogenicity in mice (21). This observation strongly suggested that ExlB and ExlA synthesis is controlled by as yet unidentified regulatory pathways.

With this objective in mind, we undertook to analyze the regulation of exlBA expression in strain IHMA879472 (IHMA87), a PA7-like strain isolated recently from a urinary infection. This strain is able to secrete ExlA, exhibits high ExlA-dependent cytotoxicity on different eukaryotic cell lines, and can be genetically manipulated (21, 25). We found that exlBA is under the control of cAMP and its cognate receptor Vfr, which regulate the expression of acute virulence factors in the classical P. aeruginosa strains. We further demonstrate that the absence of a functional Vfr in PA7 accounts for its reduced cytotoxicity.

RESULTS

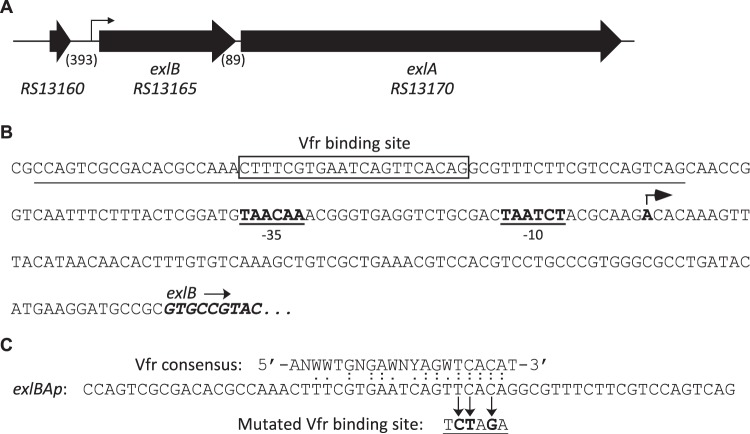

The exlBA promoter region contains a putative Vfr binding site.

ExlBA constitutes a T5SS belonging to the “b” subgroup, also called a two-partner secretion (TPS) system, whose determinants are commonly encoded in a single transcriptional unit (26, 27). As depicted in Fig. 1A, the exlB and exlA genes are in the same orientation, separated by 89 bp, and are predicted in PA7 to form an operon without the presence of an intergenic transcriptional terminator (28; www.pseudomonas.com). We sought the transcription start site (TSS) of exlBA mRNA using a circularization approach and identified one nucleotide located 91 bp upstream from the exlB start codon as the TSS candidate, and predicted putative “−10/−35” sequences using BPROM (29; www.softberry.com) (Fig. 1B). Because the −10 and −35 sequences were poorly conserved, we validated the existence of the promoter by site-directed mutagenesis. First, we introduced a reporter lacZ gene directly into the exlA locus, creating a transcriptional reporter in the wild-type (WT) strain. Then we mutated the −10 and −35 boxes directly on the chromosome, which affected the exlBA expression in vivo (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). By examining the promoter sequence using Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools (RSAT) (30; http://embnet.ccg.unam.mx/rsa-tools/) and the Vfr consensus binding sequence (31), we identified a putative binding site for the transcription factor Vfr, CTTTCGTGAATCAGTTCACA centered at around 95 bp upstream from the TSS of exlBA (Fig. 1B and C).

FIG 1.

Features of the exlBA chromosomal region. (A) The exlBA genes as well as the upstream gene are depicted by thick arrows with the nomenclature from Pseudomonas Genome Database website (28; www.pseudomonas.com). The lengths of intergenic sequences (in base pairs) are in parentheses. The exlBA promoter (exlBAp) region identified in this study is represented by a thin arrow. (B) Sequence of the exlBA promoter. The three first codons of exlB are in italics and boldface. The nucleotide identified as potential exlBA TSS found by circularization assay is in boldface and pinpointed by an arrow, with the corresponding putative −10 and −35 boxes indicated. The Vfr binding site (VBS) is boxed. Underlined is the 60-mer sequence used in EMSA and provided in panel C. (C) Comparison of the Vfr consensus sequence to the sequence found in exlBAp. The mutated VBS used in EMSA and created in the chromosome of the VBM mutant is also indicated.

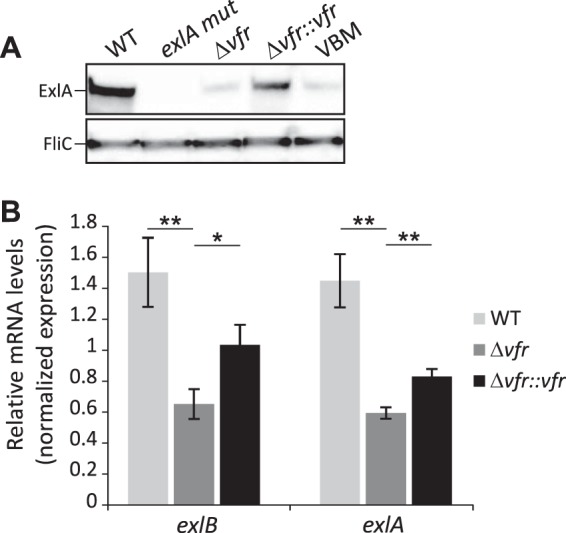

Expression of both exlB and exlA requires Vfr.

To examine the possible role of Vfr in exlBA regulation, we deleted the vfr gene in the ExlA-secreting IHMA87 strain and assessed the impact of the loss of Vfr on exlBA expression. We tested secretion of ExlA in vitro and observed a clear reduction of its secretion in the Δvfr mutant that was restored upon complementation of the strain with the wild-type copy of the gene (Fig. 2A). Then we measured the impact of vfr deletion on exlB and exlA mRNA levels by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and observed a significant reduction of both genes' expression in strains lacking Vfr. The reduced expression was partially restored upon complementation (Fig. 2B; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). These results verify that Vfr is required for exlBA expression.

FIG 2.

Vfr regulates ExlA secretion and exlBA expression. (A) The secretion of ExlA by the indicated strains grown in LB medium. The VBM strain carries a mutation in the VBS present in the exlBA promoter. Immunoblots of 100-fold-concentrated secretomes revealing the ExlA protein and FliC, used as a loading control. (B) RT-qPCR analysis of exlB and exlA relative expression in the wild-type (WT), the vfr mutant, and complemented strains grown in LB medium. The rpoD gene was used as a reference. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. The P value was determined using the Mann-Whitney U test and is indicated by * (P < 0.05) or ** (P < 0.01) when the difference between the mutant strain and the wild-type or complemented strains is statistically supported.

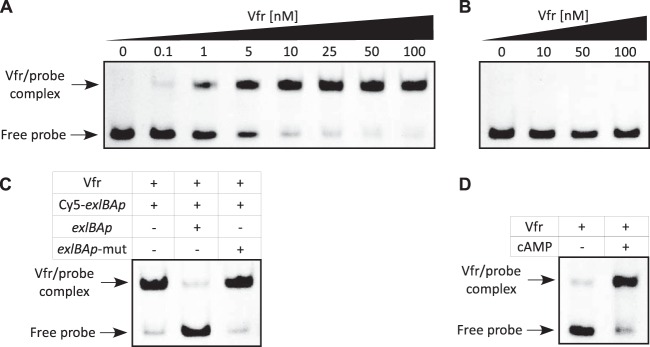

Vfr binds in vitro directly to exlBA promoter.

To test the ability of Vfr to directly interact with the exlBA promoter (exlBAp), we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using recombinant His-tagged Vfr protein. Figure 3A illustrates that Vfr binds with a high affinity to the 60-mer Cy5-labeled exlBAp fragment encompassing the putative binding site of Vfr, as revealed by the apparent equilibrium binding constant (Keq) of approximately 2.5 nM. The binding specificity was demonstrated by observing that the electrophoretic mobility of a fragment (Cy5-exlBAp mut) with mutation (in boldface) in three conserved bases in the consensus (CTTTCGTGAATCAGTCTAGA) (Fig. 1C) was not altered by Vfr, even at a high protein concentration (Fig. 3B). Moreover, Vfr binding to Cy5-exlBAp could be outcompeted with unlabeled probe containing the wild-type binding site but not with probe containing the mutated sequence (Fig. 3C). This clearly shows that the sequence present in exlBA promoter is a true Vfr binding site (VBS).

FIG 3.

Vfr binds specifically to exlBA promoter in a cAMP-dependent manner. (A and B) The recombinant His6-Vfr protein was incubated with 0.5 nM Cy5-labeled exlBAp probe (A) or the mutated exlBAp-mut probe (B) for 15 min before electrophoresis. Arrows indicate the positions of unbound free probes and Vfr-promoter probe complexes. The concentrations of Vfr used in the assay are also shown above each gel. (C) His6-Vfr (50 nM) was incubated with 0.5 nM Cy5-exlBAp probe, and where indicated, a 200-fold excess of unlabeled wild-type or mutated probe was added to the reaction mixture prior to incubation. (D) His6-Vfr (50 nM) was incubated with Cy5-exlBAp probe (0.5 nM) in the presence or absence of 20 μM cAMP in the binding buffer, as indicated. Note that in panels A, B, and C, cAMP (20 μM) was provided in the binding assay.

Inactivation of vfr affects both type 4 pilus function and ExlBA-dependent cytotoxicity.

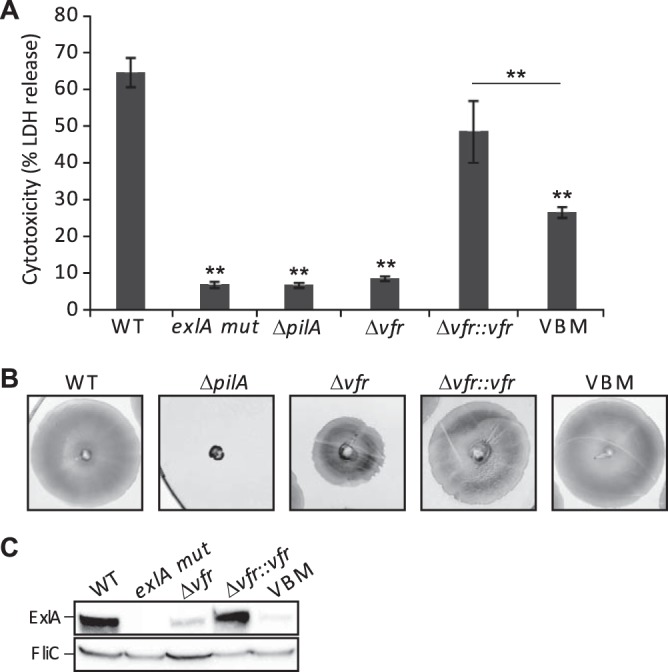

As ExlA leads to permeabilization of epithelial cell membranes and cell death (19, 25), we directly measured the impact of the vfr deletion on the cytotoxicity of the ExlA-producing strain IHMA87. The absence of Vfr strongly reduced the cytotoxicity of this strain toward A549 epithelial cells to a level similar to that observed with an ExlA-deficient strain (IHMA87 exlA mut). Additionally, the phenotype was restored to an almost wild-type level in the complemented strain (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Vfr controls synthesis of TFP and ExlBA, and both are required for cytotoxicity. (A) ExlA-dependent cytotoxicity on A549 epithelial cells of the wild type (WT), various mutants, and the complemented strains. Cytotoxicity was measured after 4.5 h of incubation with the bacteria added at an MOI of 10. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the bars indicate the standard deviations. The P value (P < 0.01) was determined using a Mann-Whitney U test and is indicated by ** when the difference between the WT strain and each mutant is statistically supported. (B) Twitching ability of the indicated strains after 48 h at 37°C. The twitching area was visualized following staining of the plates with Coomassie blue. (C) Analysis of ExlA secreted by the different strains after a 2-h infection of A549 cell monolayers. Proteins from cell culture medium were TCA precipitated and used in an immunoblot analysis with anti-ExlA and anti-FliC antibody probes. FliC was used as a loading control.

Vfr is a global regulator and was shown to modulate the expression of several virulence factors in the PAO1- and PA14-like strains. For instance, Vfr regulates directly the transcription of the fimS-algR locus, with AlgR activating the expression of fimU pilVWXY1Y2E, whose products are required for type 4 pilus (TFP) synthesis (32–34). The VBS identified in the fimS promoter of PAO1 (31) is also present in the one of IHMA87 (28; www.pseudomonas.com), suggesting that the TFP regulation is conserved. The twitching motility that relies on TFP was impaired in IHMA87 Δvfr, although to a lesser extent than when the major TFP subunit PilA was absent (IHMA87 ΔpilA). Introduction of a copy of vfr corrected the motility defect of the mutant strain (Fig. 4B).

The Vfr-dependent regulation of TFP is significant, because ExlA cytotoxicity is facilitated by functional TFP (25) (Fig. 4A). To distinguish the effect of Vfr on TFP from the one on ExlBA during eukaryotic cell infection, we introduced the mutations in the VBS directly on the exlBA promoter in the chromosome by replacing the original VBS with the 3-base-mutated sequence (Fig. 1C) shown not to interact with Vfr in the EMSA (Fig. 3B and C). In this VBS-mutated strain (VBM), the ExlA secretion was reduced to a level similar to that found in the vfr mutant in both liquid medium (LB) (Fig. 2A) and during eukaryotic cell infection (Fig. 4C). This further confirms the direct regulation of exlBA expression by the transcriptional regulator. The VBM strain displayed a cytotoxic phenotype on epithelial cells intermediate between those observed for the wild-type strain and the Δvfr strain (Fig. 4A). Therefore, both the TFP and ExlBA are regulated by Vfr, and Vfr-dependent activation of exlBA expression during cell infection is required for full cytotoxicity.

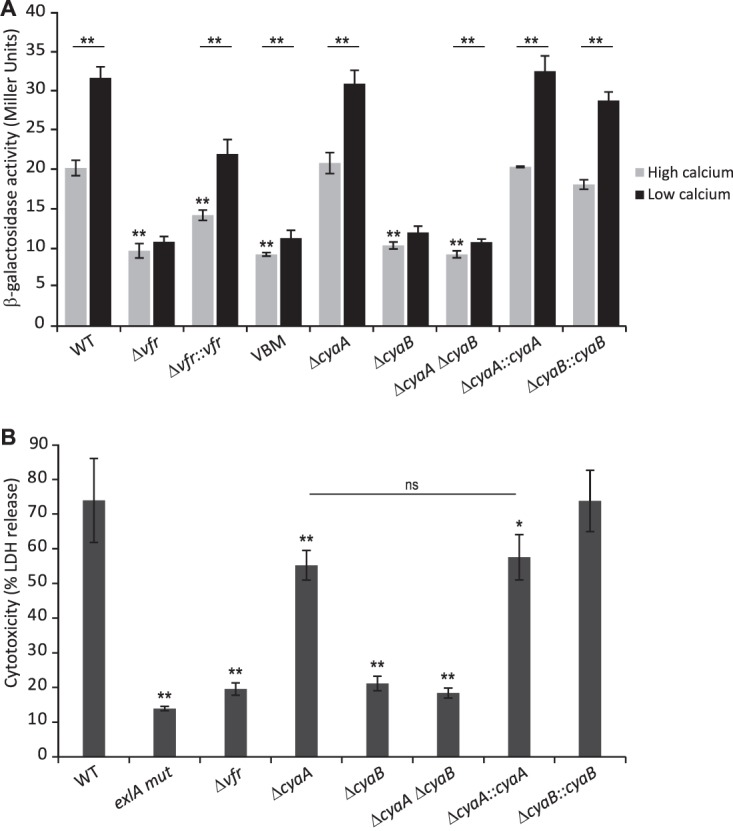

exlBA expression requires cAMP.

Vfr controls gene expression in response to levels of the second messenger cAMP, as binding of the allosteric cAMP molecule increases its DNA-binding activity to target promoters (31, 35–37). However, Vfr regulation of the QS regulator-encoding lasR gene is cAMP independent (36). Using the EMSA, we have demonstrated that cAMP is required for in vitro binding of Vfr to the exlBA promoter, as the recombinant His6-Vfr shifted the fluorescent probe only in the presence of the cyclic nucleotide (Fig. 3D). In P. aeruginosa, the cAMP levels can be modulated by calcium concentrations (38) and EGTA-induced calcium depletion of the medium has been shown to increase intracellular cAMP levels (33). We assessed the effect of different cAMP levels on exlBA expression in vivo by introducing the lacZ gene into exlA in the vfr mutant, its complemented version, and the strain with mutated VBS (VBM), creating transcriptional reporters, and then comparing their activities to that of the IHMA87 exlA::lacZ strain. When the calcium chelator EGTA was added to the medium, we observed increased β-galactosidase activity in the wild-type strain (Fig. 5A). This effect was abolished in the vfr mutant, in which exlBA expression was decreased and became “blind” to EGTA addition, but was restored in the complemented strain. As expected, the β-galactosidase activities in the latter strain were lower because of the reduced amount of Vfr in the complemented strain compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. S2). Moreover, the VBM mutant carrying mutation of the VBS in exlBA promoter exhibited exlBA expression similar to that seen in the vfr mutant (Fig. 5A). These data further confirmed that the expression of exlBA in vivo requires both Vfr and cAMP since cAMP is needed to promote Vfr binding.

FIG 5.

Vfr controls exlBA expression in a cAMP-dependent manner. (A) β-Galactosidase activities of the indicated wild-type (WT), mutant, and complemented strains carrying a chromosomal exlA-lacZ transcriptional fusion. Strains were grown in LB medium supplemented with CaCl2 (high-calcium condition) or EGTA-MgCl2 (low-calcium condition) at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.5. (B) ExlA-dependent cytotoxicity on A549 epithelial cells of the indicated wild-type (WT), vfr, cyaA, and/or cyaB mutant, and corresponding complemented strains measured after 4.5 h of infection (MOI of 10). The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations. The P value was determined using Mann-Whitney U test and is indicated above the error bars by * (P < 0.05) or ** (P < 0.01) when the difference from the wild-type strain is statistically supported. In panel A, the asterisks above the horizontal line compare each strain under the two different growth conditions. Please note that in panel B, while the ΔcyaA mutant seems slightly less cytotoxic than the wild-type strain, its phenotype is not complemented (ns, not supported by statistics) and is probably due to genetic manipulation.

CyaB is the adenylate cyclase controlling ExlA activity.

Production and degradation of intracellular cAMP are tightly controlled by adenylate cyclases (ACs) and phosphodiesterases (PDEs) to ensure homeostasis. In PAO1, three ACs have been identified: CyaA, the cytosolic class I AC; CyaB, the membrane-bound class III AC; and ExoY, the exotoxin secreted by the T3SS and active only in eukaryotic cells (reviewed in reference 39). Examination of the IHMA87 genome identified cyaA and cyaB genes, while it lacked exoY. This is in accordance with the previously noted absence of the genes for the T3SS and the effectors—a distinctive feature of the PA7-like strains (17, 22).

To address which AC provides to Vfr the cAMP molecule required for exlBA expression, we created individual deletions in cyaA and cyaB in the IHMA87 background and combined the two mutations in a single strain. We then created the exlA-lacZ transcriptional fusion in the mutants and assessed the effect of the cya mutations on exlA-lacZ expression. Only the absence of cyaB impaired the activation of exlBA expression under the conditions of calcium limitation (Fig. 5A). Moreover, inactivation of both cya genes did not reduce further the promoter activity and reintroduction of the cyaB copy restored the wild-type phenotype of IHMA87 ΔcyaB.

We also examined the ExlA-dependent cytotoxicity on epithelial A549 cells of the different mutants to determine which AC might affect the cAMP/Vfr pathway during host cell infection. As shown in Fig. 5B, solely the absence of cyaB affected strongly the cytotoxicity of IHMA87 to levels similar to that observed with IHMA87 Δvfr. Inactivation of both genes did not further decrease cytotoxicity, and introduction of a copy of the cyaB gene into the IHMA87 ΔcyaB strain reversed the cytotoxicity to wild-type levels (Fig. 5B). Therefore, in IHMA87 the expression of exlBA relies on the secondary messenger cAMP produced by CyaB, when grown under laboratory conditions and during the interaction with mammalian cells.

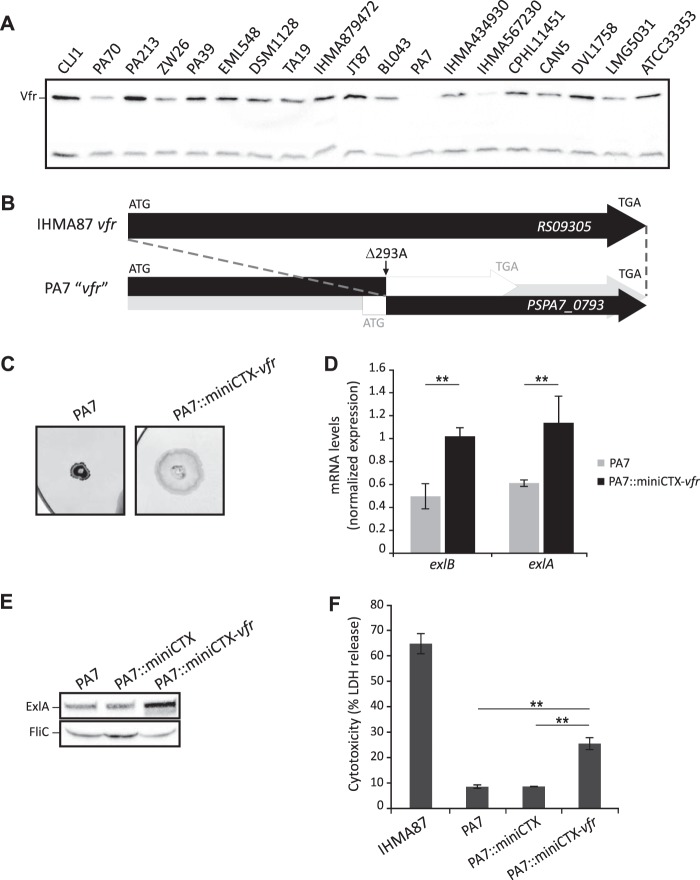

The absence of ExlBA-dependent cytotoxicity in PA7 is due to a frameshift in the vfr gene.

We recently analyzed several phenotypes of PA7-like strains, including cytotoxicity on various cell types and different types of motility (21). Compared to the ExlA-producing strains IHMA87 and CLJ1 (19), the reference PA7 strain secreted negligible amounts of ExlA in vitro, was poorly cytotoxic toward eukaryotic cells, and was devoid of TFP-dependent twitching motility (21). All these traits being consistent with the phenotypes of the IHMA87 Δvfr mutant, we wondered whether Vfr synthesis or function was affected in PA7. We first assessed the amount of Vfr in the PA7 strain by immunoblotting and then extended our analysis to all the PA7-like strains from our collection (21). We observed different Vfr levels in cells grown in calcium limiting medium. For example, we detected large amounts in CLJ1 and IHMA87 and smaller amounts in PA70 and IHMA567230, and the protein was absent from PA7 (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Natural mutation in vfr of P. aeruginosa PA7 impacts TFP synthesis and ExlA-dependent virulence. (A) Immunoblot of the cytosolic fraction of the different PA7-like strains analyzed in reference 21. The upper band corresponds to Vfr, while the lower band is a contaminant used as a loading control. (B) The PSPA7_0793 gene is shorter than the corresponding RS09305 gene of IHMA87 (AZPAE15042) (28; www.pseudomonas.com). Deletion of the adenine at 293 creates a frameshift that leads to two putative ORFs, as shown in the box. The 3′ ORF corresponds to the annotation “vfr.” (C) Twitching abilities of PA7 and PA7 containing the miniCTX-vfr plasmid integrated into the att chromosomal site strains. To visualize the twitching area, after 48 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were stained with Coomassie blue. (D) Complementation of PA7 with vfr impacts mRNA levels of exlB and exlA genes, as assessed by RT-qPCR. The relative mRNA quantity of the PA7 strain compared to the PA7::miniCTX-vfr strain is shown. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the P values (**, P < 0.01). (E) Immunoblot analysis of ExlA secreted by the different PA7 strains grown in LB. FliC is used as a loading control. (F) ExlA-dependent cytotoxicity on A549 epithelial cells of IHMA87, PA7, and PA7 containing in the chromosome either the empty miniCTX1 plasmid or the miniCTX-vfr plasmid. Cytotoxicity was measured after 4.5 h of infection at an MOI of 10. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations. The P value (P < 0.01), determined using Mann-Whitney U test, is indicated by ** when the difference between the PA7 strains is statistically supported.

The comparison of the vfr gene in PA7 (28; www.pseudomonas.com) to that of IHMA87 revealed the absence of the adenine 293, resulting in a frameshift that creates two putative overlapping ORFs. The first one encodes a 161-amino-acid (aa)-long protein consisting of N-terminal 98 aa identical to Vfr, and the other, annotated as vfr (PSPA7_0793), encodes a putative 118-aa-long protein translated from a wrong-start codon corresponding to the 116-aa C-terminal portion of Vfr (Fig. 6B). The base deletion in the PA7 vfr gene was confirmed by PCR amplification and resequencing.

In order to examine whether the phenotypes of PA7 were due to vfr inactivation or additional mutations, we introduced one copy of intact vfr into the PA7 chromosome and verified the production of Vfr in this complemented strain (Fig. S2). The PA7::miniCTX-vfr strain exhibited an increased ability to twitch (Fig. 6C) and higher exlA and exlB mRNA levels compared to the wild-type PA7 (Fig. 6D), thus producing higher ExlA secretion (Fig. 6E). The introduction of functional vfr in PA7 also led to the creation of a strain with increased cytotoxicity toward the A549 cells (Fig. 6F), demonstrating the effect of vfr expression on PA7 virulence. These results clearly show that the presence of a functional Vfr regulator is required for full cytotoxicity of PA7-like strains as seen in the other strains of this clade.

DISCUSSION

Since its discovery in 1994 (37), Vfr has emerged as an important global regulator of P. aeruginosa virulence. This transcriptional factor, which belongs to the cAMP receptor protein (CRP) family, affects directly or indirectly the expression of more than 200 genes, controlled either positively or negatively (33, 40). The virulence traits positively regulated by Vfr include the TFP, QS, exotoxin A, T2SS, and T3SS, among others. However, when overproduced, the Vfr protein can also impact negatively flagellar biosynthesis by inhibiting the synthesis of the major flagellar regulator FleQ. In this work, we extended the regulon of Vfr by demonstrating that it controls directly and positively the expression of the main virulence factor of the PA7-like strains, namely, the T5SS ExlBA. Therefore, the two major virulence determinants in P. aeruginosa, T3SS and ExlBA, are encoded by genes that are mutually excluded from the genomes of different P. aeruginosa groups (PAO1/PA14 versus PA7), but they share similarities in their mechanisms of action and regulation. Effectively, both systems require close host cell contact for translocation and action of their toxins, and the interaction is mediated by extracellular appendages, the P. aeruginosa TFP (25, 41). Furthermore, for full T3SS- and ExlA-dependent cytotoxicity, they both require CyaB, the main cAMP-producing enzyme, and the cAMP receptor Vfr (33; this work). While Vfr was known to control T3SS synthesis for over a decade (33), the underlying mechanism was deciphered only recently (42). Here, we demonstrated the cAMP-dependent binding of Vfr to the VBS identified in the exlBA promoter of PA7-like strains and its requirement for cytotoxicity toward eukaryotic cells. Deletions of cyaB and/or vfr in a classical T3SS-positive strain led to an attenuated phenotype with reduced colonization and dissemination in a mouse model of lung infection, mostly through downregulation of T3SS (43). Thus, we can infer the same cAMP/Vfr regulatory pathway requirement in vivo for the virulence of the PA7-like strains that relies on exolysin ExlA, supported by our previous observation that PA7 is avirulent in mice (19).

The P. aeruginosa T5bSS ExlBA is a new TPS found in strains of the PA7 group. TPSs are typically encoded by contiguous genes organized in a single operon, with the gene encoding the transporter preceding the sequence encoding the toxin (26). However, alternate gene organizations for other TPS-encoding genes have been described. For example, the P. aeruginosa PdtBA system is encoded by two noncontiguous genes transcribed in different transcriptional units, but they are coregulated (27). We showed that the exlBA genes are transcribed as a single transcriptional unit from the promoter controlled by Vfr. The exlBA expression is low when the IHMA87 strain is cultivated in rich liquid medium, as suggested by very low activity of a reporter lacZ fusion in the wild-type IHMA87 strain. This could reflect the poorly conserved −35 (TAACAA) and −10 (TAATCT) sequences that deviate from the consensus sequences (−35 TTGACA/−10 TATAAT) but govern exlBA transcription (Fig. S1), suggesting that other factors besides Vfr might be required for an efficient transcription.

Vfr binding to its target promoters relies on VBS whose location relative to the TSSs determines the mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Vfr downregulates expression of few genes where the VBS overlaps the −10 sequence or is located just downstream of the TSS, as reported, respectively, for fleQ and one of the four rhlR promoters (40, 44). For them, Vfr binding probably reduces transcription initiation by impairing the RNA polymerase recruitment. However, most genes are positively controlled by Vfr, the VBSs being located upstream of the TSS at variable distance. For instance, in algD far upstream (FUS) promoter, VBS is centered at bp −362.5 (31), while it is at bp −58 from the TSS at the vfr promoter (36). The VBSs can also overlap the −35 sequence, as reported for the ptxR T2 and exsA promoters (42, 45). Consequently, Vfr employs several mechanisms for RNA polymerase recruitment to promote gene expression, similar to what was observed for the CRP of Escherichia coli, with which it shares 67% sequence identity (37, 46, 47). With its VBS centered at around bp −97, the exlBA promoter should belong to a class I CRP promoter type, whereby Vfr recruits RNA polymerase by interacting with the C-terminal domain of its α-subunit (α-CTD). The in vitro binding of Vfr on exlBA promoter occurs with a high affinity (Keq of ≈2.5 nM), placing it in the top range of those previously reported for other target sequences of this regulator (36, 42). As for most genes, binding activity of Vfr depends on the cyclic nucleotide cAMP and factors affecting its cellular levels.

In the PA7 reference strain, two key regulatory genes, vfr and pqsR (mvfR), carry mutations and are inactivated. Although the base deletion within vfr was not identified in the original report (17), it is reminiscent of the annotated pqsR pseudogene resulting from the deletion of two consecutive bases, the guanidine and cytosine at positions 698/699 (28; www.pseudomonas.com). This pqsR mutation accounts for some phenotypic differences between PA7 and PAO1 (17), as the PQS system controls the expression of several virulence factors such as elastase, pyocyanin, and rhamnolipids (48). We demonstrated that the absence of Vfr also impacts PA7 virulence, particularly by reducing TFP and ExlBA synthesis, required for full cytotoxicity. The importance of the Vfr regulator in P. aeruginosa physiology and adaptation during chronic infection is highlighted by mutations in its gene commonly found among CF isolates (49). Loss of regulatory genes affecting virulence is a well-known means of reducing the aggressive phenotype of CF isolates and promotes chronic long-term infections (49, 50). Interestingly, spontaneous mutations in vfr were also observed in PAO1 after several cycles of static growth, leading to a secretion-defective and impaired-motility phenotype that could potentially benefit the bacterium under these conditions (51).

Recently we found that other Pseudomonas species, such as Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas protegens and Pseudomonas entomophila, express ExlA-like toxins which are responsible for pyroptotic death of macrophages (52). Orthologs of vfr and cyaB genes are present in these species, inferring a common regulatory mechanism. Identification of the signaling events triggering cAMP synthesis upon host cell contact, as well as other regulatory circuits controlling ExlBA synthesis, will be the next steps toward understanding of the virulence exerted by P. aeruginosa taxonomic outliers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The P. aeruginosa strains used in this study are described in Table 1. Bacteria were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) at 37°C with agitation. To assess the effect of calcium on exlBA expression, overnight cultures were diluted in LB to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. When cultures reached an OD600 of 0.5, either 5 mM calcium (high-calcium condition) or 20 mM MgCl2–5 mM EGTA at pH 8.0 (low-calcium condition) was added, and growth was continued until the OD600 reached 1.0 to 1.5. For the introduction of plasmids into P. aeruginosa, strains were selected following mating with E. coli donors on LB plates supplemented with 25 μg/ml irgasan. The following antibiotics were added when needed: 75 μg/ml gentamicin (Gm) and 75 μg/ml tetracycline (Tc).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant properties | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| IHMA879472 (IHMA87) | Wild-type strain (urinary infection)a | 58 |

| IHMA87 exlA mut | IHMA87 with pEXG2 inserted into exlA gene (Gmr) | 25 |

| IHMA87 ΔpilA | IHMA87 with nonpolar pilA deletion | 25 |

| IHMA87 Δvfr | IHMA87 with nonpolar vfr deletion | This work |

| IHMA87 Δvfr::vfr | IHMA87 Δvfr with miniCTX-comp-vfr (Tcr) | This work |

| IHMA87 VBM | IHMA87 carrying a mutation in the Vfr binding site upstream of exlB gene, in exlBA promoter | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaA | IHMA87 with nonpolar cyaA deletion | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaA::cyaA | IHMA87 ΔcyaA with miniCTX-cyaA (Tcr) | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaB | IHMA87 with nonpolar cyaB deletion | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaB::cyaB | IHMA87 ΔcyaB with miniCTX-cyaB (Tcr) | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaA ΔcyaB | IHMA87 with nonpolar cyaA and cyaB deletion | This work |

| IHMA87 exlA::lacZ | IHMA87 with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| IHMA87 Δvfr exlA::lacZ | IHMA87 Δvfr with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| IHMA87 Δvfr::vfr exlA::lacZ | IHMA87 Δvfr::vfr with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| IHMA87 VBM exlA::lacZ | IHMA87 VBM with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaA exlA::lacZ | IHMA87 ΔcyaA with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaA::cyaA exlA::lacZ | IHMA87 ΔcyaA::cyaA with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaB exlA::lacZ | HMA87 ΔcyaB with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaB::cyaB exlA::lacZ | IHMA87 ΔcyaB::cyaB with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| IHMA87 ΔcyaA ΔcyaB exlA::lacZ | IHMA87 ΔcyaA ΔcyaB with promoterless lacZ in exlA | This work |

| PA7 | Wild-type strain (nonrespiratory infection) | 17 |

| PA7::miniCTX | PA7 with miniCTX1 empty vector (Tcr) | This work |

| PA7::miniCTX-vfr | PA7 with miniCTX-comp-vfr (Tcr) | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| Top10 | Chemically competent cells | Invitrogen |

| BL21 Star(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm rne131(DE3) | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR-Blunt II-TOPO | Commercial cloning vector (Knr) | Invitrogen |

| pRK2013 | Helper plasmid conjugative properties (Knr) | 59 |

| pEXG2 | Allelic exchange vector (Gmr) | 60 |

| pEXG2-Mut-vfr | pEXG2 carrying SOE-PCR fragment for deletion of vfr | This work |

| pEXG2-VBM | pEXG2 carrying SOE-PCR fragment for mutation of Vfr binding site in pexlBA | This work |

| pEXG2-Mut-cyaA | pEXG2 carrying SOE-PCR fragment for deletion of cyaA | This work |

| pEXG2-Mut-cyaB | pEXG2 carrying SOE-PCR fragment for deletion of cyaB | This work |

| pEXG2-exlBA-lacZ | pEXG2 carrying lacZ integrated within exlBA fragment for integration into chromosome | This work |

| miniCTX1 | Site-specific integrative plasmid (att B site, Tcr) | 61 |

| miniCTX-comp-vfr | miniCTX carrying vfr gene | This work |

| miniCTX-cyaA | miniCTX carrying cyaA gene | This work |

| miniCTX-cyaB | miniCTX carrying cyaB gene | This work |

| pET15BVP | Expression vector for inducible production of N-terminally His6-tagged proteins (Apr) | 62 |

| pET15BVP-purif-Vfr | Expression vector pET15BVP carrying PCR fragment for Vfr overproduction | This work |

Referred to as AZPAE15042 at www.pseudomonas.com.

Plasmids and genetic manipulation.

The plasmids utilized in this study and the primers used for PCR are listed in Table 1 (and see Table S1 in the supplemental material). To generate P. aeruginosa deletion mutants, upstream and downstream flanking regions of vfr, cyaA, and cyaB were fused by the splicing by overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR) procedure using the appropriate primer pairs (53). The resulting fragments of 873, 884, and 850 bp were cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector and then subcloned into the PstI-BamHI (for vfr) or HindIII-XhoI (for cya) sites of the pEXG2 plasmid to obtain the pEXG2-Mut-vfr, pEXG2-Mut-cyaA, and pEXG2-Mut-cyaB plasmids, respectively. Each wild-type gene with its own promoter region was amplified by PCR and sequenced. To complement the mutants, the DNA fragments containing the cyaA (3,385-bp) and cyaB (1,998-bp) genes were inserted into the SmaI site of the integrative vector miniCTX1 by sequence- and ligation-independent cloning (SLIC) (54), leading to miniCTX-cyaA and miniCTX-cyaB. The vfr fragment (1,220 bp) was cloned in the BamHI-HindIII sites of the plasmid, leading to miniCTX-comp-vfr. To create the transcriptional exlA-lacZ fusion, the upstream region of exlA, the lacZ gene, and the downstream region of exlA were amplified using the SLIC_pEXG2_exlBA′_F/SLIC_exlBA′_lacZ_R, SLIC_lacZ_F/SLIC_lacZ_R and SLIC_lacZ_exlA′_F/SLIC_exlA′_pEXG2_R primer pairs. The resulting fragments of 700, 3,123, and 700 bp were then cloned into SmaI-cut pEXG2 by SLIC. Flanking exlA regions were designed so that the lacZ coding sequence with its own ribosome binding site can be inserted in frame after the third codon of exlA. The miniCTX and pEXG2-derived vectors were transferred into P. aeruginosa IHMA87 or PA7 strains by triparental mating using pRK2013 as a helper plasmid. For allelic exchange using the pEXG2 plasmids, cointegration events were selected on LB plates containing Irgasan and gentamicin. Single colonies were then plated on NaCl-free LB agar plates containing 10% (wt/vol) sucrose to select for the loss of plasmid, and the resulting sucrose-resistant strains were checked for gentamicin sensitivity and mutant genotype.

For overproduction of Vfr in E. coli, the vfr gene was PCR amplified using IHMA87 genomic DNA as the template, and the amplicon was inserted into NdeI-BamHI sites of the pET15b plasmid. All the constructions were verified by sequencing.

Mapping of the 5′ end using circularization of exlB cDNA.

The procedure for 5′-end mapping was carried out as previously described (55) with some modification. Total RNA was isolated from IHMA87 at an OD600 of 2.0 using hot phenol-chloroform extraction. The residual DNAs in 30 μg of total RNA were removed with Turbo DNase I (4 U; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Following phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, 15 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using 5′-phosphorylated exlB gene-specific primer (R_exlB+60; 2 pmol) and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (400 U, 40 μl of reaction volume; Thermo Fisher Scientific). After reverse transcription, the residual RNAs were removed using RNase H (5 U) and RNase If (50 U). The cDNA was purified using the Oligo Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo Research) with a reduced ethanol volume (200 μl) and recovered with 19 μl of nuclease-free water. The 8.75 μl of cDNA was used for the circularization reaction (15 μl of reaction mixture volume, 100 U of CircLigase II; Epicentre). The control cDNA was incubated under the same condition in the absence of CircLigase II. After incubation at 60°C for 2 h, the reaction was terminated by further incubating at 80°C for 10 min. The circularized cDNA (4 μl) was used as the template in an amplification of the junction sequence using GoTaq green master mix (40 μl of reaction mixture volume; Promega) and exlB primer pairs (F_exlB+4 and R_exlB+3). The cycling conditions were 94°C for 3 min, followed by 36 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 55°C for 45 s, 72°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 2 min. PCR products were separated and eluted by 2% agarose and cloned into pJET2.1 vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Positive clones obtained from colony PCR were sequenced with the pJET reverse primer. All the primers used for circularization are listed in Table S1.

Cell culture and cytotoxicity assay.

The epithelial lung carcinoma cell line A549 (ATCC CCL-185) was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), at 37°C, in 5% CO2. The day before the infection, the A549 cells were seeded in a 48-well tissue culture plate (Falcon) at 8 × 104 cells/well in fresh RPMI medium. For the infection, RPMI medium was replaced by nonsupplemented endothelial basal medium 2 (EBM2; Lonza). Monolayers were infected with bacteria at an OD600 of ≈1.0 and at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. The bacterial cytotoxicity was determined by measuring the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the supernatant 4.5 h postinfection using the Roche cytotoxicity LDH detection kit. The negative controls were noninfected cells, and the positive controls were cells lysed by the addition of Triton X-100. The degree of cytotoxicity was calculated by determining the percentage of cytotoxicity compared to that of the positive control. The experiments were performed at least in triplicate.

ExlA secretion analysis.

ExlA proteins were precipitated and concentrated using the sodium deoxycholate-trichloroacetic acid (DOC-TCA) method, either in LB cultures or after cell infection, as previously described (25). Briefly, proteins secreted by the bacteria were collected when the bacterial cultures reached an OD600 of ≈1.0, or after 2 h of A549 infection at an MOI of 10. The secreted proteins were precipitated by adding DOC at a final concentration of 0.02% for 30 min at 4°C. TCA was then added to 10%, and the solution was incubated overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation for 15 min at 15,000 × g at 4°C, the pellet was resuspended in Laemmli loading buffer corresponding to 1/100 of the original volume. Samples were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto 0.2-μm-pore polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham) for Western immunoblotting. Rabbit polyclonal primary antibodies raised against the recombinant C-terminal part of ExlA and against the purified ExlA protein with its C-terminal part deleted (52) were mixed at a 1:1,000 dilution. The anti-FliC antibodies, used at a 1:1,000 dilution, were raised in rabbits (Biotem) with the recombinant FliC4 protein (residues 43 to 443 of the FliC b-type). His6-FliC4 was expressed from pET28a.TEV-FliC4 and purified by affinity chromatography using the HIS60 Ni SuperFlow cartridge (Clontech Laboratories). Before immunization of rabbits, the tag was cleaved off by the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease and the FliC4 protein was further purified by size exclusion chromatography using HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 Prep grade column (GE Healthcare). The immunoblots were developed using horseradish peroxidase (HRP [Sigma])-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies at a 1:40,000 dilution. The detection was performed with the Luminata Classico Western HRP substrate kit (Millipore) and analyzed using a Chemidoc (Bio-Rad).

Vfr analysis in PA7-like strains.

Bacterial cultures (30 ml at an OD600 of ≈1.0) were centrifuged for 10 min at 6,000 × g and resuspended in 600 μl of a mixture of 25 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole (pH 8.0), supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After sonication (3× 150 J), the broken cells were removed by centrifugation at 22,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. A 7.5-μl concentration of each sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE (15% gel) and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The primary anti-Vfr antibody was used at a 1:25,000 dilution and the secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody at 1:50,000.

Twitching motility assay.

For the twitching motility assay, bacteria were inoculated at the plastic-agar interface of agar plates containing 10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, 1% agar, and 10 g/liter NaCl and kept at 37°C for 48 h. The agar medium was then removed, and the twitching diameter was observed after staining with 0.1% Coomassie blue (21).

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase activity was assayed when the bacterial cultures reached an OD600 of ≈1.5 as described previously (56), with technical details reported in reference 57.

RT-qPCR.

Total RNA from 2.0 ml of cultures (OD600 of ≈1.0) was extracted either with hot phenol followed by ethanol precipitation or using the TRIzol Plus RNA purification kit (Invitrogen) and then treated with DNase I (amplification grade; Invitrogen). The yield, purity, and integrity of RNA were further evaluated on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and by agarose gel migration. cDNA synthesis was carried out using 3 μg of RNA with the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen) in the presence or absence of the SuperScript III RT enzyme to assess the absence of genomic DNA. The CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad) was used to PCR amplify the cDNA, and the quantification was based on use of SYBR green fluorescent molecules. Two microliters of cDNA was incubated with 5 μl of Gotaq master mix (2×) (Promega) and reverse and forward specific primers at a final concentration of 125 nM in a total volume of 10 μl. The cycling parameters of the real-time PCR were 95°C for 2 min (for activation of the Taq polymerase), 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 45 s, and finally a melting curve from 65°C to 95°C by increments of 0.5°C for 5 s to assess the specificity of the amplification. To generate standard curves, serial dilutions of the cDNA pool of the CLJ strains were used. The experiments were performed in duplicate with 3 biological replicates for each strain, and the results were analyzed with the CFX Manager software (Bio-Rad). The relative expression of mRNAs was calculated using the quantification cycle (ΔΔCq) method relative to rpoD reference Cq values. The sequences of primers were designed using Primer3Plus and are given in Table S1.

Vfr purification.

Overproduction of His6-Vfr was performed in E. coli BL21(DE3)Star harboring pET15BVP grown at 37°C in ampicillin-containing LB medium. Overnight culture was diluted to an OD600 of 0.05, and expression was induced at an OD600 of 0.6 with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). After 3 h of growth, bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and resuspended in a mixture of 25 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole (pH 8.0) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The bacteria were then broken using an M110-P Microfluidizer (Microfluidics). After centrifugation at 4°C and 30,000 rpm for 30 min, the soluble fraction was directly loaded onto a 1-ml nickel column (Protino Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid [NTA]; Macherey-Nagel). The column was washed with buffer containing increasing imidazole concentrations (20, 40, and 60 mM) using an ÄKTA purifier system (GE Healthcare), and the proteins were eluted with 200 mM imidazole. Aliquots from the peak protein fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the fractions containing Vfr were pooled and dialyzed against buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM KCl, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Tween 20 [pH 7.0]) as previously described (36).

EMSA.

The 60-mer DNA probes (5′Cy5-pexlBA_EMSA_F/pexlBA_EMSA_R, pexlBA_EMSA_F/pexlBA_EMSA_R, 5′Cy5-pexlBA_mut_EMSA_F/pexlBA_mut_EMSA_R, and pexlBA_mut_EMSA_F/pexlBA_mut_EMSA_R) were generated by annealing complementary pairs of oligonucleotides as described in Table S1. The probes (0.5 nM) were incubated for 5 min at 25°C in binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]) containing 25 ng/μl poly(dI-dC) (×1,330) and, unless indicated otherwise, 20 μM cAMP (Sigma-Aldrich). Vfr protein was added at the indicated concentrations in a final reaction volume of 20 μl and incubated for an additional 15 min at 25°C. Samples were immediately loaded on a native 5% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) polyacrylamide gel and run at 100 V and 4°C with cold 0.5× TBE buffer. Fluorescence imaging was performed using the Chemidoc MP apparatus. EMSAs were repeated a minimum of two times, and the representative gels are presented.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were carried out using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. P values of <0.05 and <0.01 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Katrina Forest for the Vfr antiserum, Annabelle Varrot for the pET28a.TEV-FliC4 plasmid, and Peter Panchev for proofreading the manuscript. International Health Management Association (IHMA, USA) kindly provided the P. aeruginosa IHMA879472 strain.

This work was supported by grants from Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-15-CE11-0018-01), the Laboratory of Excellence GRAL (ANR-10-LABX-49-01), and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (Team FRM 2017, DEQ20170336705). We further acknowledge support from CNRS, INSERM, CEA, and Grenoble Alps University. Alice Berry received a Ph.D. fellowship from the CEA Irtelis program.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00135-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moradali MF, Ghods S, Rehm BH. 2017. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lifestyle: a paradigm for adaptation, survival, and persistence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:39. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, Olson MV. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigue A, Quentin Y, Lazdunski A, Mejean V, Foglino M. 2000. Two-component systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: why so many? Trends Microbiol 8:498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01833-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galan-Vasquez E, Luna B, Martinez-Antonio A. 2011. The regulatory network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb Inform Exp 1:3. doi: 10.1186/2042-5783-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wurtzel O, Yoder-Himes DR, Han K, Dandekar AA, Edelheit S, Greenberg EP, Sorek R, Lory S. 2012. The single-nucleotide resolution transcriptome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in body temperature. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002945. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cattoir V, Narasimhan G, Skurnik D, Aschard H, Roux D, Ramphal R, Jyot J, Lory S. 2013. Transcriptional response of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to human respiratory mucus. mBio 3:e00410-. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00410-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez-Lozano M, Marvig RL, Tulstrup MV, Molin S. 2014. Expression of antisense small RNAs in response to stress in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Genomics 15:783. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coggan KA, Wolfgang MC. 2012. Global regulatory pathways and cross-talk control pseudomonas aeruginosa environmental lifestyle and virulence phenotype. Curr Issues Mol Biol 14:47–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jimenez PN, Koch G, Thompson JA, Xavier KB, Cool RH, Quax WJ. 2012. The multiple signaling systems regulating virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:46–65. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balasubramanian D, Schneper L, Kumari H, Mathee K. 2013. A dynamic and intricate regulatory network determines Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. Nucleic Acids Res 41:1–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suh SJ, Runyen-Janecky LJ, Maleniak TC, Hager P, MacGregor CH, Zielinski-Mozny NA, Phibbs PV Jr, West SE. 2002. Effect of vfr mutation on global gene expression and catabolite repression control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 148:1561–1569. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-5-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hengge R. 2009. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valentini M, Filloux A. 2016. Biofilms and cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling: lessons from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other bacteria. J Biol Chem 291:12547–12555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.711507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Y, Yang H, Qiao M, Jin S. 2011. MexT regulates the type III secretion system through MexS and PtrC in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 193:399–410. doi: 10.1128/JB.01079-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikkelsen H, McMullan R, Filloux A. 2011. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa reference strain PA14 displays increased virulence due to a mutation in ladS. PLoS One 6:e29113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sall KM, Casabona MG, Bordi C, Huber P, de Bentzmann S, Attree I, Elsen S. 2014. A gacS deletion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolate CHA shapes its virulence. PLoS One 9:e95936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy PH, Tetu SG, Larouche A, Elbourne L, Tremblay S, Ren Q, Dodson R, Harkins D, Shay R, Watkins K, Mahamoud Y, Paulsen IT. 2010. Complete genome sequence of the multiresistant taxonomic outlier Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA7. PLoS One 5:e8842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dingemans J, Ye L, Hildebrand F, Tontodonati F, Craggs M, Bilocq F, De Vos D, Crabbe A, Van Houdt R, Malfroot A, Cornelis P. 2014. The deletion of TonB-dependent receptor genes is part of the genome reduction process that occurs during adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the cystic fibrosis lung. Pathog Dis 71:26–38. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elsen S, Huber P, Bouillot S, Coute Y, Fournier P, Dubois Y, Timsit JF, Maurin M, Attree I. 2014. A type III secretion negative clinical strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa employs a two-partner secreted exolysin to induce hemorrhagic pneumonia. Cell Host Microbe 15:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boukerb AM, Marti R, Cournoyer B. 2015. Genome sequences of three strains of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA7 clade. Genome Announc 3:e01366-. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01366-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reboud E, Elsen S, Bouillot S, Golovkine G, Basso P, Jeannot K, Attree I, Huber P. 2016. Phenotype and toxicity of the recently discovered exlA-positive Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains collected worldwide. Environ Microbiol 18:3425–3439. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber P, Basso P, Reboud E, Attree I. 18 July 2016. Pseudomonas aeruginosa renews its virulence factors. Environ Microbiol Rep doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freschi L, Jeukens J, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, Boyle B, Dupont MJ, Laroche J, Larose S, Maaroufi H, Fothergill JL, Moore M, Winsor GL, Aaron SD, Barbeau J, Bell SC, Burns JL, Camara M, Cantin A, Charette SJ, Dewar K, Deziel E, Grimwood K, Hancock RE, Harrison JJ, Heeb S, Jelsbak L, Jia B, Kenna DT, Kidd TJ, Klockgether J, Lam JS, Lamont IL, Lewenza S, Loman N, Malouin F, Manos J, McArthur AG, McKeown J, Milot J, Naghra H, Nguyen D, Pereira SK, Perron GG, Pirnay JP, Rainey PB, Rousseau S, Santos PM, Stephenson A, Taylor V, Turton JF, Waglechner N, Williams P, Thrane SW, Wright GD, Brinkman FS, Tucker NP, Tummler B, Winstanley C, Levesque RC. 2015. Clinical utilization of genomics data produced by the International Pseudomonas aeruginosa Consortium. Front Microbiol 6:1036. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cadoret F, Ball G, Douzi B, Voulhoux R. 2014. Txc, a new type II secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA7, is regulated by the TtsS/TtsR two-component system and directs specific secretion of the CbpE chitin-binding protein. J Bacteriol 196:2376–2386. doi: 10.1128/JB.01563-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basso P, Ragno M, Elsen S, Reboud E, Golovkine G, Bouillot S, Huber P, Lory S, Faudry E, Attree I. 2017. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pore-forming exolysin and type IV pili cooperate to induce host cell lysis. mBio 8:e02250-. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02250-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leo JC, Grin I, Linke D. 2012. Type V secretion: mechanism(s) of autotransport through the bacterial outer membrane. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367:1088–1101. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faure LM, Llamas MA, Bastiaansen KC, de Bentzmann S, Bigot S. 2013. Phosphate starvation relayed by PhoB activates the expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa sigmavreI ECF factor and its target genes. Microbiology 159:1315–1327. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.067645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winsor GL, Griffiths EJ, Lo R, Dhillon BK, Shay JA, Brinkman FS. 2016. Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas Genome Database. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D646–D653. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solovyev V, Salamov A, Seledtsov I, Vorobyev D, Bachinsky A. 2011. Automatic annotation of bacterial community sequences and application to infections diagnostic, p 346–353. In Bioinformatics 2011. Proceedings of the International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods, and Algorithms, Rome, Italy, 26 to 29 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medina-Rivera A, Defrance M, Sand O, Herrmann C, Castro-Mondragon JA, Delerce J, Jaeger S, Blanchet C, Vincens P, Caron C, Staines DM, Contreras-Moreira B, Artufel M, Charbonnier-Khamvongsa L, Hernandez C, Thieffry D, Thomas-Chollier M, van Helden J. 2015. RSAT 2015: Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W50–W56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanack KJ, Runyen-Janecky LJ, Ferrell EP, Suh SJ, West SE. 2006. Characterization of DNA-binding specificity and analysis of binding sites of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa global regulator, Vfr, a homologue of the Escherichia coli cAMP receptor protein. Microbiology 152:3485–3496. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beatson SA, Whitchurch CB, Sargent JL, Levesque RC, Mattick JS. 2002. Differential regulation of twitching motility and elastase production by Vfr in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 184:3605–3613. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.13.3605-3613.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfgang MC, Lee VT, Gilmore ME, Lory S. 2003. Coordinate regulation of bacterial virulence genes by a novel adenylate cyclase-dependent signaling pathway. Dev Cell 4:253–263. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo Y, Zhao K, Baker AE, Kuchma SL, Coggan KA, Wolfgang MC, Wong GC, O'Toole GA. 2015. A hierarchical cascade of second messengers regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface behaviors. mBio 6:e02456-. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02456-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serate J, Roberts GP, Berg O, Youn H. 2011. Ligand responses of Vfr, the virulence factor regulator from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 193:4859–4868. doi: 10.1128/JB.00352-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuchs EL, Brutinel ED, Jones AK, Fulcher NB, Urbanowski ML, Yahr TL, Wolfgang MC. 2010. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Vfr regulator controls global virulence factor expression through cyclic AMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Bacteriol 192:3553–3564. doi: 10.1128/JB.00363-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West SE, Sample AK, Runyen-Janecky LJ. 1994. The vfr gene product, required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A and protease production, belongs to the cyclic AMP receptor protein family. J Bacteriol 176:7532–7542. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7532-7542.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inclan YF, Huseby MJ, Engel JN. 2011. FimL regulates cAMP synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 6:e15867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lory S, Wolfgang M, Lee V, Smith R. 2004. The multi-talented bacterial adenylate cyclases. Int J Med Microbiol 293:479–482. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dasgupta N, Ferrell EP, Kanack KJ, West SE, Ramphal R. 2002. fleQ, the gene encoding the major flagellar regulator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is sigma70 dependent and is downregulated by Vfr, a homolog of Escherichia coli cyclic AMP receptor protein. J Bacteriol 184:5240–5250. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5240-5250.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundin C, Wolfgang MC, Lory S, Forsberg A, Frithz-Lindsten E. 2002. Type IV pili are not specifically required for contact dependent translocation of exoenzymes by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb Pathog 33:265–277. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2002.0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsden AE, Intile PJ, Schulmeyer KH, Simmons-Patterson ER, Urbanowski ML, Wolfgang MC, Yahr TL. 2016. Vfr directly activates exsA transcription to regulate expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system. J Bacteriol 198:1442–1450. doi: 10.1128/JB.00049-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith RS, Wolfgang MC, Lory S. 2004. An adenylate cyclase-controlled signaling network regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. Infect Immun 72:1677–1684. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1677-1684.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Croda-Garcia G, Grosso-Becerra V, Gonzalez-Valdez A, Servin-Gonzalez L, Soberon-Chavez G. 2011. Transcriptional regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhlR: role of the CRP orthologue Vfr (virulence factor regulator) and quorum-sensing regulators LasR and RhlR. Microbiology 157:2545–2555. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.050161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrell E, Carty NL, Colmer-Hamood JA, Hamood AN, West SE. 2008. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ptxR by Vfr. Microbiology 154:431–439. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Busby S, Ebright RH. 1999. Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP). J Mol Biol 293:199–213. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Browning DF, Busby SJ. 2016. Local and global regulation of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:638–650. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diggle SP, Cornelis P, Williams P, Camara M. 2006. 4-Quinolone signalling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: old molecules, new perspectives. Int J Med Microbiol 296:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith EE, Buckley DG, Wu Z, Saenphimmachak C, Hoffman LR, D'Argenio DA, Miller SI, Ramsey BW, Speert DP, Moskowitz SM, Burns JL, Kaul R, Olson MV. 2006. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:8487–8492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeukens J, Boyle B, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, Ouellet MM, Aaron SD, Charette SJ, Fothergill JL, Tucker NP, Winstanley C, Levesque RC. 2014. Comparative genomics of isolates of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa epidemic strain associated with chronic lung infections of cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One 9:e87611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fox A, Haas D, Reimmann C, Heeb S, Filloux A, Voulhoux R. 2008. Emergence of secretion-defective sublines of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 resulting from spontaneous mutations in the vfr global regulatory gene. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1902–1908. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02539-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basso P, Wallet P, Elsen S, Soleilhac E, Henry T, Faudry E, Attree I. 2017. Multiple Pseudomonas species secrete exolysin-like toxins and provoke caspase-1-dependent macrophage death. Environ Microbiol 19:4045–4064. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li MZ, Elledge SJ. 2007. Harnessing homologous recombination in vitro to generate recombinant DNA via SLIC. Nat Methods 4:251–256. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polidoros AN, Pasentsis K, Tsaftaris AS. 2006. Rolling circle amplification-RACE: a method for simultaneous isolation of 5′ and 3′ cDNA ends from amplified cDNA templates. BioTechniques 41:35–36, 38, 40. doi: 10.2144/000112205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thibault J, Faudry E, Ebel C, Attree I, Elsen S. 2009. Anti-activator ExsD forms a 1:1 complex with ExsA to inhibit transcription of type III secretion operons. J Biol Chem 284:15762–15770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kos VN, Deraspe M, McLaughlin RE, Whiteaker JD, Roy PH, Alm RA, Corbeil J, Gardner H. 2015. The resistome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in relationship to phenotypic susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:427–436. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03954-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Figurski DH, Helinski DR. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rietsch A, Vallet-Gely I, Dove SL, Mekalanos JJ. 2005. ExsE, a secreted regulator of type III secretion genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:8006–8011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503005102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoang TT, Kutchma AJ, Becher A, Schweizer HP. 2000. Integration-proficient plasmids for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: site-specific integration and use for engineering of reporter and expression strains. Plasmid 43:59–72. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arora SK, Ritchings BW, Almira EC, Lory S, Ramphal R. 1997. A transcriptional activator, FleQ, regulates mucin adhesion and flagellar gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a cascade manner. J Bacteriol 179:5574–5581. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5574-5581.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.