ABSTRACT

Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) in Staphylococcus aureus is a poly-glycerophosphate polymer anchored to the outer surface of the cell membrane. LTA has numerous roles in cell envelope physiology, including regulating cell autolysis, coordinating cell division, and adapting to environmental growth conditions. LTA is often further modified with substituents, including d-alanine and glycosyl groups, to alter cellular function. While the genetic determinants of d-alanylation have been largely defined, the route of LTA glycosylation and its role in cell envelope physiology have remained unknown, in part due to the low levels of basal LTA glycosylation in S. aureus. We demonstrate here that S. aureus utilizes a membrane-associated three-component glycosylation system composed of an undecaprenol (Und) N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) charging enzyme (CsbB; SAOUHSC_00713), a putative flippase to transport loaded substrate to the outside surface of the cell (GtcA; SAOUHSC_02722), and finally an LTA-specific glycosyltransferase that adds α-GlcNAc moieties to LTA (YfhO; SAOUHSC_01213). We demonstrate that this system is specific for LTA with no cross recognition of the structurally similar polyribitol phosphate containing wall teichoic acids. We show that while wild-type S. aureus LTA has only a trace of GlcNAcylated LTA under normal growth conditions, amounts are raised upon either overexpressing CsbB, reducing endogenous d-alanylation activity, expressing the cell envelope stress responsive alternative sigma factor SigB, or by exposure to environmental stress-inducing culture conditions, including growth media containing high levels of sodium chloride.

IMPORTANCE The role of glycosylation in the structure and function of Staphylococcus aureus lipoteichoic acid (LTA) is largely unknown. By defining key components of the LTA three-component glycosylation pathway and uncovering stress-induced regulation by the alternative sigma factor SigB, the role of N-acetylglucosamine tailoring during adaptation to environmental stresses can now be elucidated. As the dlt and glycosylation pathways compete for the same sites on LTA and induction of glycosylation results in decreased d-alanylation, the interplay between the two modification systems holds implications for resistance to antibiotics and antimicrobial peptides.

KEYWORDS: lipoteichoic acid, glycosylation, cell envelope stress, SigB, cell envelope, teichoic acids

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is an opportunistic pathogen that commonly inhabits the pharynx and skin (1, 2). In the past two decades, this bacterium has made headlines due to the clinical rise of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Despite its namesake, MRSA is capable of resisting various beta-lactam antibiotics and not just methicillin (3). Beta-lactams and other commonly used antibiotics, such as vancomycin, target the biosynthetic machineries that assemble the Gram-positive bacteria cell wall. The biosynthesis of these cell wall components is essential for MRSA's fitness and survival and thus presents an attractive target for antibiotic development (4–7).

The cell wall of S. aureus is comprised of a thick peptidoglycan matrix embedded with various surface-associated proteins and unique phosphodiester linked alditol polymers called teichoic acids (TA) (8). There are two types of TAs, namely, wall teichoic acid (WTA) and lipoteichoic acid (LTA). In S. aureus, WTA is comprised of polyribitol phosphate (poly-RboP) repeats anchored to the peptidoglycan via an N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc)-N-acetylmannosamine linkage unit (9), while LTA is comprised of poly-glycerophosphate (poly-GroP) repeats anchored directly to the cell membrane via a diacylglycerol-gentiobiose moiety (10–12). TAs are essential for maintaining the integrity of the cell envelope where they play numerous roles, including osmoprotection, regulating peptidoglycan autolysis, and coordinating cell division (9, 10, 13). In fact, deletion of both WTA and LTA is synthetically lethal (14, 15). The biosynthetic pathways for both forms of TAs have been established in S. aureus (9, 10). However, the biosynthesis of more complex forms of TAs in other species, as well as modifications in model TAs such as those in S. aureus, is still being elucidated. Modification of both WTA and LTA parent polymers can have vast impact on function. For instance, d-alanine (d-Ala) ester addition by the dltABCD operon has been shown to regulate autolysis during cell wall remodeling (16), localize penicillin-binding proteins (17), and confer resistance to antibiotics such as daptomycin (18) and antimicrobial peptides (19–21). The d-alanylation pathway is currently the most well defined (20, 22, 23), whereby DltA loads the carrier protein DltC with d-Ala. The functions of DltB and DltD are not as clear but are thought to transport the DltC–d-Ala intermediate across the membrane and subsequently d-alanylate TA acceptor substrates. Glycosylation of TAs has remained relatively underexamined by comparison, but recent studies have made progress in demonstrating the roles of TarM and TarS in transferring α- and β-GlcNAc, respectively, to WTA in S. aureus (24–27). WTA modification with β-GlcNAc imparts beta-lactam resistance, is critical to colonization, and plays a role alongside d-Ala modifications in cell division and morphogenesis (28, 29). Both TarS and TarM utilize cytoplasmic UDP-GlcNAc donors with glycosylation occurring before the WTA polymer is transported to the outer surface of the membrane. The TarM/TarS family of WTA glycosylases is widely distributed among TA-harboring Gram-positive bacteria and has been characterized among other Firmicutes, including in Bacillus subtilis (30).

Interestingly, a new class of integral membrane proteins (YfhO) was recently implicated in ribitol phosphate WTA glycosylation with GlcNAc moieties in Listeria monocytogenes (31). In this proposed glycosylation pathway, YfhO adds GlcNAc residues to WTA outside the cytoplasmic membrane using extracytoplasmic undecaprenol monophosphate GlcNAc (Und-P-GlcNAc) donor produced by the CsbB protein family. An analogous Listeria sp. serovar system for WTA galactosylation has also now been described (32). In the model S. aureus strain NCTC8325, there are both CsbB (SAOUHSC_00713) and YfhO (SAOUHSC_01213) orthologues, suggesting the genetic potential to glycosylate WTA as in L. monocytogenes. Instead, however, we present evidence here that the S. aureus YfhO orthologue glycosylates LTA with GlcNAc and is dependent on CsbB for donor substrate. We show that wild-type S. aureus LTA has low GlcNAc levels under normal growth conditions but that these levels are markedly elevated by either overexpressing CsbB, reducing d-alanylation, or inducing cell envelope stress using growth media containing high levels of NaCl.

RESULTS

CsbB and YfhO do not glycosylate WTA.

To examine whether CsbB-YfhO is indeed a WTA-specific glycosylation system, we first overexpressed the putative components of the membrane-bound extracellular glycosylation system in S. aureus. Typically, these systems consist of three proteins: the membrane associated Und-P-sugar glycosylase (i.e., CsbB), the integral membrane glycosyl transferase (i.e., YfhO), and an integral membrane protein involved in flipping the sugar loaded Und carrier from the cytoplasmic to the extracellular face of the membrane (40, 41). Since no flippase genes were located in proximity to either CsbB (SAOUHSC_00713) or YhfO (SAOUHSC_01213), a protein similarity search using the annotated Und-P-sugar transporter from the Shigella flexneri O-antigen glycosylation system encoded by the bacteriophage Sfx (41) was performed. A lone transporter candidate in the S. aureus genome with the same conserved domain was identified (GtcA; SAOUHSC_02722). The S. aureus GtcA protein shares 24% identity over 83% of its length (128 amino acids total) with the putative S. flexneri transporter and is predicted to have the four-transmembrane pass topology common to this transporter class. Hence, both CsbB and the putative transporter GtcA were overexpressed on a single multicopy plasmid to ensure transport would not be limiting. We transformed this plasmid into strains that were null for either of the known cytoplasmic WTA glycosylases tarM, tarS, or both, as we speculated modification could be masked by the resident GlcNAc glycosylases. Crude WTA was extracted from these strains and analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Because TarM and TarS have redundant GlcNAcylating activities differing only in anomeric configurations, the single deletion profiles were not discernible from the wild type. In the ΔtarM ΔtarS double-knockout strain from which WTA glycosylation was eliminated, nonglycosylated WTA migrated at lower molecular weights. Contrary to our expectation, simultaneous overexpression of CsbB and GtcA (PcadcsbB-gtcA) did not reestablish higher-molecular-weight WTA in the ΔtarM ΔtarS double knockout and deletion of ΔyfhO had no effect on WTA regardless of the presence of PcadcsbB-gtcA. To confirm this, WTA was purified from overexpression strains for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). The structure of WTA isolated from the different constructs was indifferent to the expression levels of CsbB-GtcA-YfhO.

CsbB and YfhO induces LTA structural heterogeneity.

Since LTA is structurally similar to WTA, we next examined whether instead LTA is the actual CsbB-GtcA-YfhO target substrate. Gründling and coworkers previously identified a galactose LTA modification system in L. monocytogenes that uses an extracytoplasmic three-component glycosylation system (42). Furthermore, GlcNAc-modified LTA has been isolated from certain S. aureus strains, although no genes have been annotated, and there also is a lack of consensus on whether LTA glycosylation occurs in all S. aureus lineages (10, 36, 43). In order to rapidly analyze LTA for glycosylation, we sought to develop a quick PAGE method to monitor LTA structure analogous to that used for WTA analysis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Initial attempts at separating purified LTA directly on PAGE were poorly resolved since no discrete bands were observed (see Fig. S2, lane 1, in the supplemental material). We posited that LTA, unlike hydrolyzed WTA, aggregates due to the covalently attached diacylglycerol moiety. In order to deacylate LTA while preserving glycosidic linkages, we screened a panel of lipases (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast to acid or base deacylation (44), pretreatment with Resinase HT (Strem Chemicals) consistently produced single-band resolution with no concurrent LTA polymer degradation upon PAGE analysis.

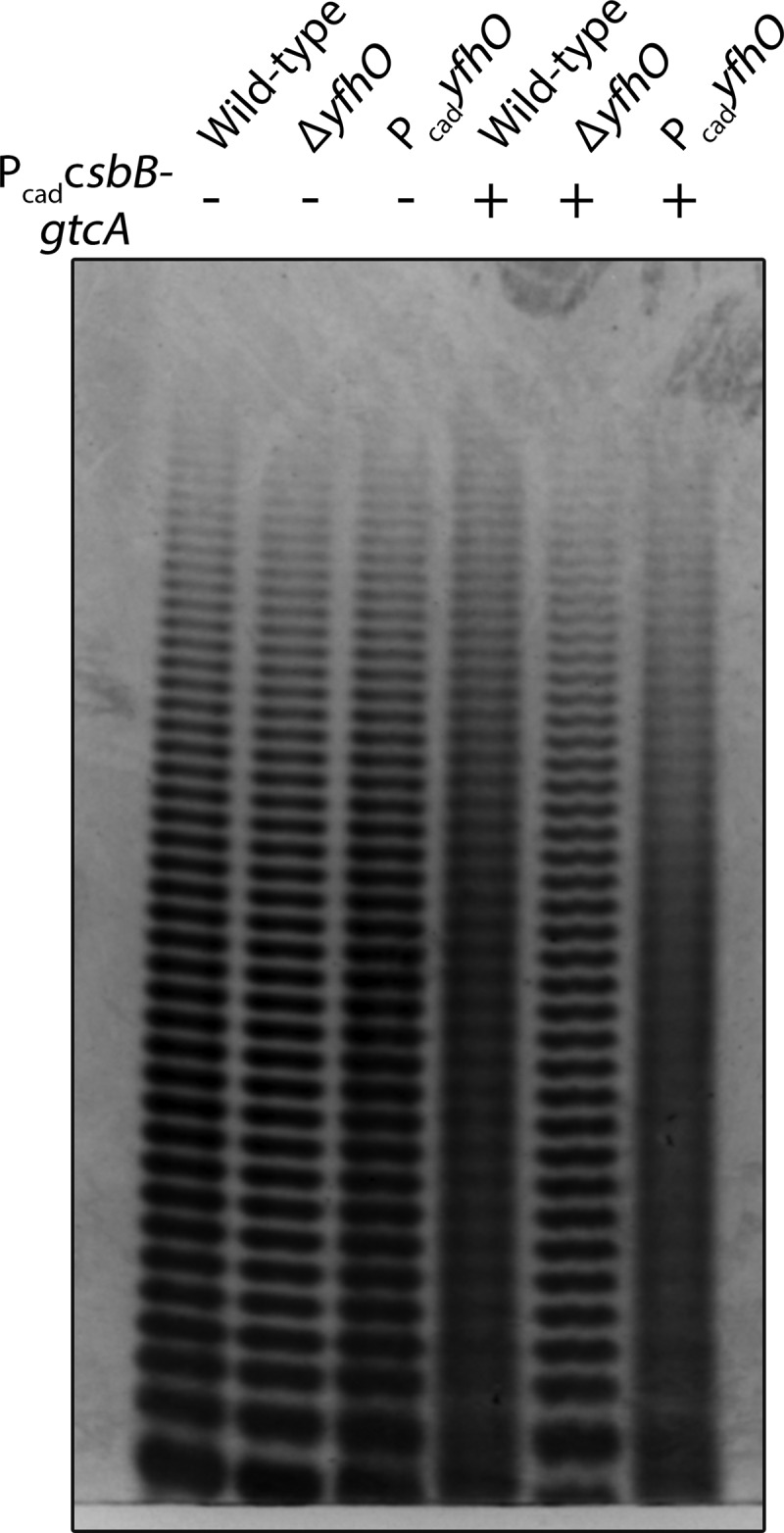

With a facile assay in hand, LTA PAGE profiles were compared to assess the effect of CsbB-GtcA-YfhO overexpression (Fig. 1). Overexpression of CsbB-GtcA caused the discrete single-band resolution to disappear and produce a “smear” in the wild type, regardless of whether YfhO was cooverexpressed or expressed at endogenous chromosomal levels. Smearing is consistent with induced LTA structural heterogeneity, as would be expected from glycosylation. Moreover, this is a YfhO-dependent phenotype since there was no effect in the ΔyfhO background even when PcadcsbB-gtcA was present. The diagnostic smearing could be restored with plasmid borne YfhO only when PcadcsbB-gtcA was also present. Hence, basal expression of YfhO from the chromosomal copy appears sufficient to modify LTA, and significant LTA modification depends on constitutive CsbB-GtcA expression.

FIG 1.

PAGE analysis of purified LTA from RN4220 derived strains. LTA was first treated with Resinase HT at pH 8.5 for 16 h to hydrolyze the lipid chains and d-Ala esters. This enabled single-band resolution of the LTA poly-GroP backbone, producing a profile consistent with minimal glycosylation in the wild type. Modification of LTA is yfhO dependent and, provided PcadcsbB-gtcA is expressed, induces a loss in band resolution. Each band indicates a poly-GroP polymer of n+1 repeat length.

CsbB and YfhO glycosylates LTA with GlcNAc.

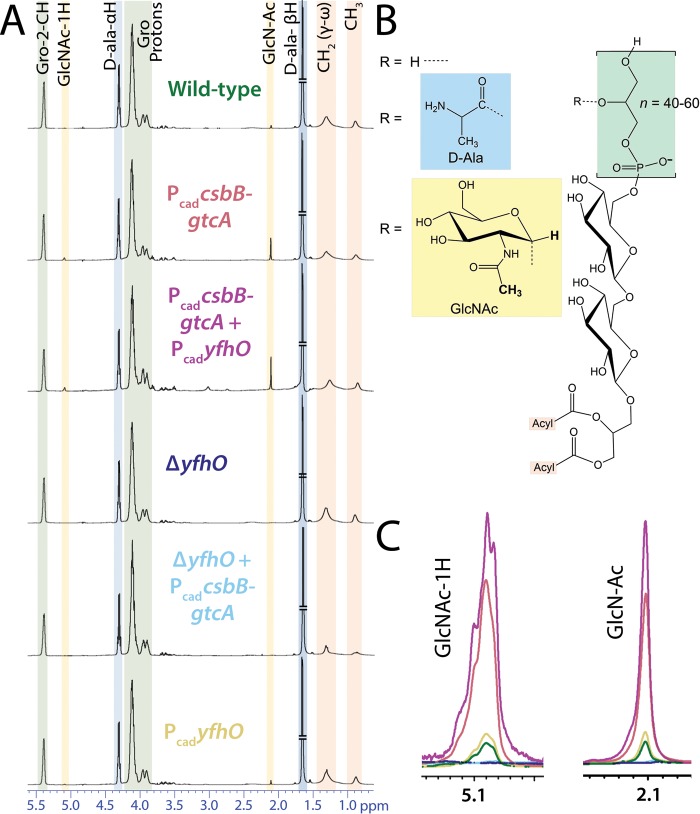

To confirm the PAGE observations and quantify the levels of glycosylation, purified LTA samples extracted from early-stationary-phase cultures of S. aureus RN4220 were analyzed by 1H NMR (Fig. 2). In wild-type RN4220, very low intensity signals with chemical shifts consistent with both the α-anomeric and methyl group protons of GlcNAc were observed (Fig. 2A). These peaks are consistent with the α-GlcNAc assignments previously made by Hartung and coworkers using LTA extracted from S. aureus subsp. aureus Rosenbach 1884 (strain H, DSM 20233) (36). However, the amount of GroP subunits modified with GlcNAc is at most 2% in comparison to the ∼15% levels previously reported in strain H LTA (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). LTA analysis from the S. aureus subsp. aureus NCTC8325 HG003 derived strain TM226 (the RN4220 strain parent lineage) likewise revealed an extremely low basal GlcNAc content. Introduction of PcadcsbB-gtcA into the RN4220 wild type increased the GlcNAc levels to 5%, whereas introduction of both PcadcsbB-gtcA and PcadyfhO further raised the GlcNAc levels to 6% (see Fig. S3 and Table S2 in the supplemental material). Deletion of chromosomal yfhO completely removed any GlcNAc related peaks, regardless of whether PcadcsbB-gtcA was present (Fig. 2C). Overexpression of YfhO alone only slightly increased the GlcNAc levels beyond the trace amount observed in the wild type (Fig. 2A, bottom panel), indicating that (lack of) expression of CsbB-GtcA is the main factor controlling LTA glycosylation levels in wild-type S. aureus.

FIG 2.

Expression of CsbB-GtcA and YfhO induces GlcNAcylation of LTA in S. aureus. (A) NMR spectra of purified LTA extracted from various strains. Shading of peaks corresponds to LTA structural components highlighted in panel B and whose integration was used in calculating d-Ala and GlcNAc percent compositions (summarized in Fig. S3; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). Strains were as follows: RN4220, wild type; TM684, PcadcsbB-gtcA; KK791, PcadcsbB-gtcA + PcadyfhO; KK737, ΔyfhO; KK753, ΔyfhO + PcadcsbB-gtcA; and KK860, PcadyfhO. (C) Signal from the α-anomeric proton (∼5.1 ppm) and the acetate proton (∼2.1 ppm) of GlcNAc (in boldface text in panel B). Spectra are color coded to match the labels in panel A.

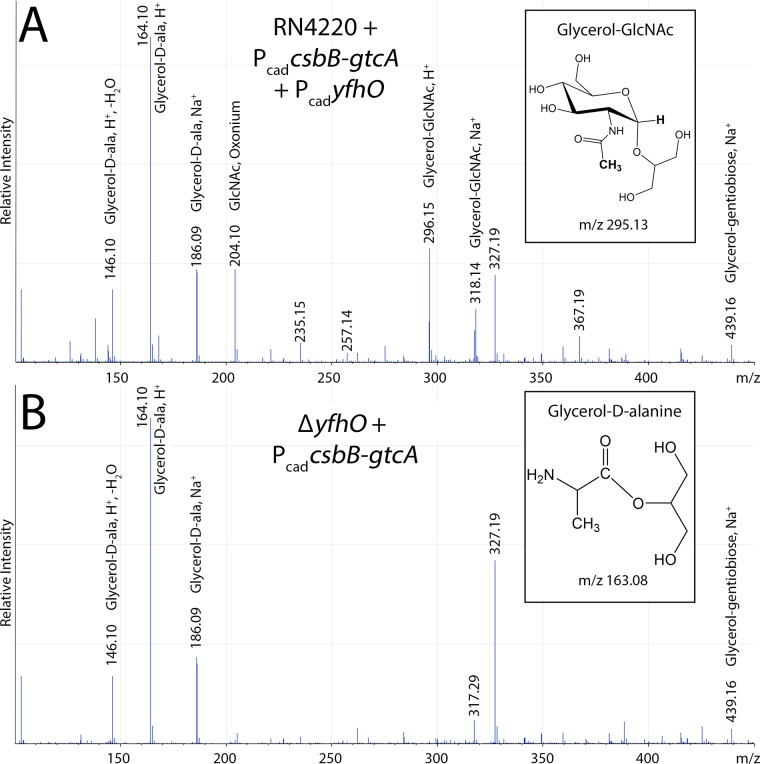

Since S. aureus elaborates many GlcNAc containing cell envelope polymers including peptidoglycan and poly-N-acetylglucosamine that could potentially contaminate LTA-purified preparations (45–47), it was necessary to unambiguously confirm covalent attachment of GlcNAc to the poly-GroP backbone. We thus adapted a hydrofluoric acid (HF)-mediated WTA depolymerization method for LTA monomer analysis by electron spray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) (48–50). LTA extracted from two different strains harboring PcadcsbB-gtcA were compared; one control sample from a ΔyfhO background (KK753) and the other from a strain cooverexpressing YfhO (Fig. 3). From both strains, the dominant mass profile observed was a family of peaks consistent with protonated (dehydrated) and sodiated glycerol-d-Ala LTA monomer (m/z = 164.1, 146.1, and 186.09, respectively). Thus, the majority of notoriously labile d-Ala esters (23) remained largely intact during HF treatment. In addition, a number of ions could be assigned to the acylglycerol moiety and gentiobiose core from both samples (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Three prominent strain-specific ion signals corresponding to GlcNAc were observed at m/z 204.10 (free GlcNAc, oxonium), 296.15 (glycerol-GlcNAc, H+), and 318.14 (glycerol-GlcNAc, Na+) when CsbB-GtcA-YfhO was overexpressed (Fig. 3A). In contrast, no GlcNAc signals were detected in the ΔyfhO background (Fig. 3B), confirming both covalent GlcNAc attachment to LTA and a complete dependence on YfhO activity for glycosylation.

FIG 3.

Electron spray ionization-mass spectrometry of KK791 (RN4220 + PcadcsbB-gtcA + PcadyfhO) (A) and KK753 (ΔyfhO + PcadcsbB-gtcA) (B). The GlcNAc-related ions are observed at m/z 204.10 (GlcNAc, oxonium), m/z 296.15 (glycerol-GlcNAc, H+), and m/z 318.14 (glycerol-GlcNAc, Na+) in KK791, whereas these signals are absent in KK753. A complete list of assignable signals is provided in Table S3 in the supplemental material.

Depletion of d-Ala promotes high level LTA glycosylation.

Based on the NMR data (Fig. 2; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material), C2 GroP hydroxyls from wild-type RN4220 LTA are ∼85% substituted by d-Ala, a finding which is in agreement with previous reports (20, 36). The level of d-alanylation among the purified LTA extracts remained in the 80 to 90% range, regardless of how much GlcNAc modification (up to 6% maximum) was achieved through the overexpression of CsbB-GtcA-YfhO. We hypothesized that this glycosylation ceiling may not solely be due to limited gene expression but rather is capped by competition with the d-alanylation machinery. Simply put, if LTA GroP approaches 90% occupation by d-Ala, the maximum amount of GlcNAc substitution can only be 10% since both moieties are attached to the C2 hydroxyl of the poly-GroP backbone.

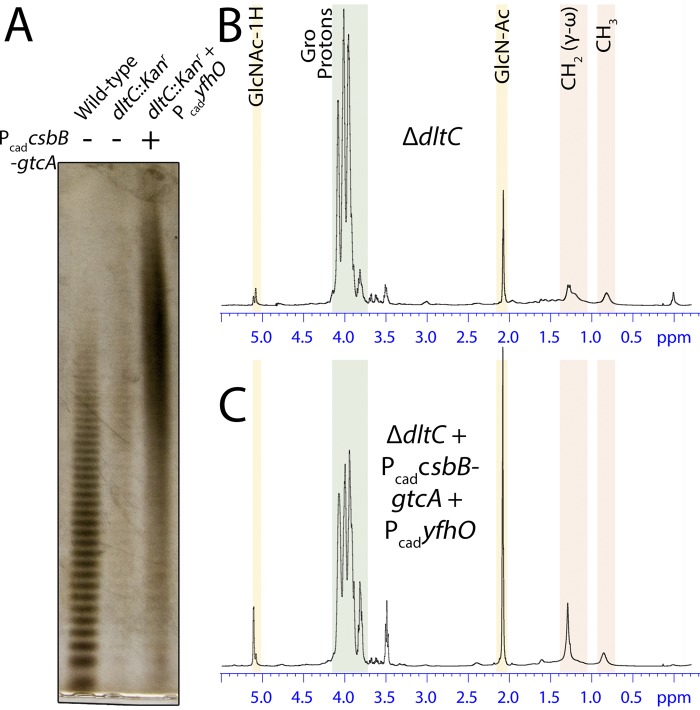

To test this hypothesis, we replaced the d-Ala carrier protein dltC with a kanamycin resistance cassette and analyzed LTA by PAGE and 1H NMR (Fig. 4). While the overall amount of LTA extracted from the dltC::Kanr strain was significantly lower than in the wild type, it was apparent that the extracted LTA migrated more slowly than that of the wild-type parent (Fig. 4A). We then overexpressed CsbB-GtcA-YfhO in the dltC::Kanr background, which restored the levels of extractable LTA to near wild-type levels. In addition, LTA from this strain was shifted to a higher molecular mass and pronouncedly smeared, as would be expected for high-level GlcNAc modification. To quantify this, LTA extracted from both strains was analyzed by 1H NMR (Fig. 4B). The levels of d-Ala were significantly lower in the dltC::Kanr background, as would be expected. More importantly, the ΔdltC LTA was now 8% substituted with GlcNAc (∼4.5-fold higher than in the dltC+ parent strains). Overexpression of CsbB-GtcA-YfhO in the dltC::Kanr mutant further elevated GlcNAc levels to 28% (Fig. 4C), indicating substitution in one of every four GroP repeating units. This degree of substitution was by far the highest observed in any of the tested constructs (see Fig. S3 and Table S2 in the supplemental material), suggesting that a combination of overexpression of the three-component glycosylation system in tandem with lowered d-alanylation activity is the most effective route to highly glycosylated LTA.

FIG 4.

Depletion of d-Ala promotes GlcNAc modification of LTA. (A) PAGE of column-purified LTA extracted from wild-type RN4220, TM582 (dltC::Kanr), and KK868 (dltC::Kanr + PcadcsbB-gtcA + PcadyfhO) strains. When CsbB-GtcA-YfhO are overexpressed, a slowly migrating smear diagnostic of substantial LTA modification is observed. (B and C) NMR spectra of LTA isolated from dltC::Kanr (B) and dltC::Kanr (C) strains overexpressing CsbB-GtcA-YfhO.

Sodium chloride-induced cell stress increases GlcNAc modification of LTA.

Our results indicated that expression of CsbB-GtcA (or, conversely, a lack of chromosomal expression in the wild type) is the key genetic determinant controlling whether LTA is modified with GlcNAc residues in S. aureus. These two genes putatively load Und-P with GlcNAc inside the cytoplasm (CsbB) and flip the sugar-loaded carrier to the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane (GtcA) in a three-component glycosylation system completed by the LTA α-O-GlcNAc transferase (YfhO) whose chromosomal expression appeared to be sufficient to realize GlcNAcylation. To narrow which of the two genes (CsbB or GtcA) may be the dominant factor in regulating LTA glycosylation, we overexpressed them singly on a plasmid and monitored the resulting LTA structure by PAGE (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Since the expression of CsbB was clearly the most important determinant in inducing LTA modification, we next focused on potential regulation of the CsbB promoter to identify environmental conditions that may induce LTA GlcNAcylation in the wild type. Bioinformatics analysis using the comprehensive transcript data set of Mäder et al. suggests that SAOUHSC_00713 is under the control of the cell wall stress-induced alternative sigma factor SigB (51). However, RN4220 is known to be deficient in SigB expression due to a small deletion in rsbU, a component of the SigB activation cascade (52). Regulation experiments were thus conducted in the rsbU+ strain TM226 that, like RN4220, also does not appreciably modify LTA with GlcNAc under standard growth conditions. To further corroborate intact csbB regulation in TM226, sigB was cloned into a multicopy overexpression vector under the control of the protein A (spa) gene promoter (53). Gene expression analysis by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) confirmed 5-fold overexpression of sigB, resulting in overexpression of both csbB (2.4-fold) and the sigB expression control marker asp23 gene (18-fold) (54). Once more, LTA was now highly modified with GlcNAc at 10% when sigB was overexpressed.

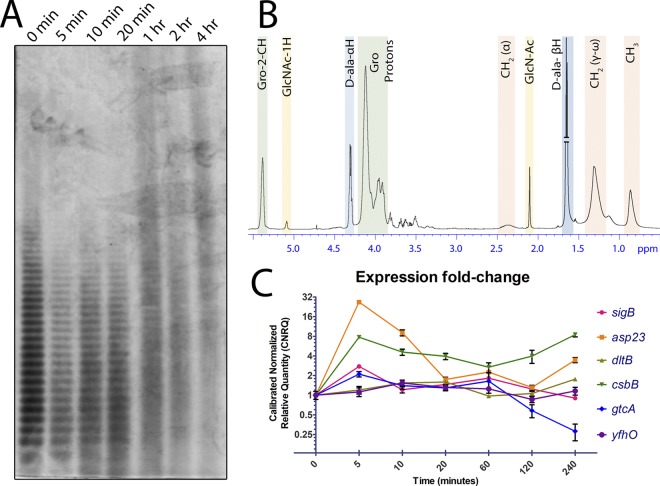

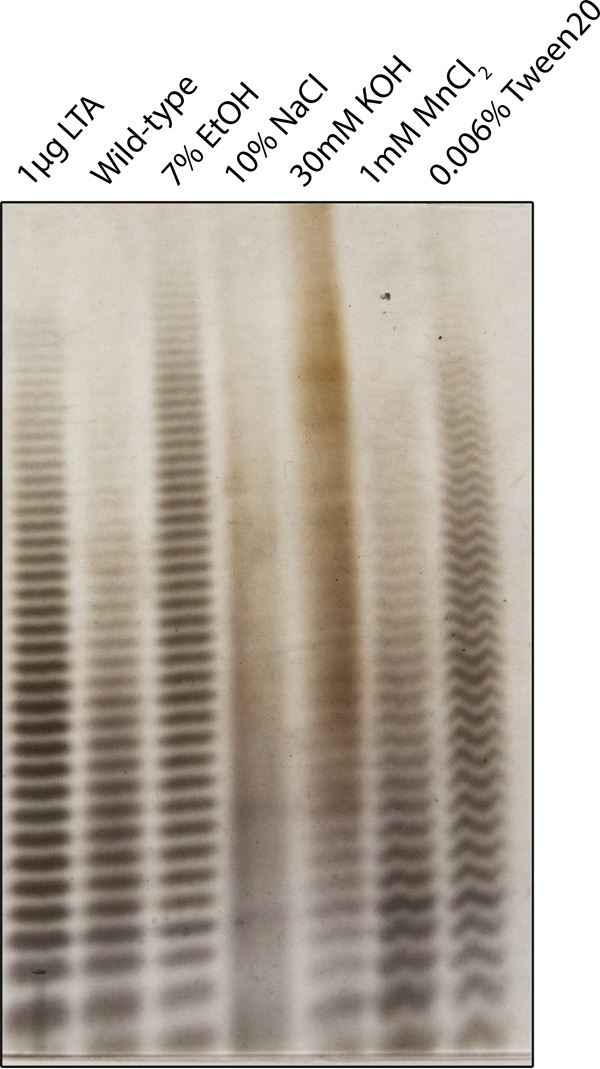

To determine whether LTA GlcNAcylation is indeed controlled by SigB under environmentally induced stress cues, S. aureus was subjected to a panel of known cell envelope stress-inducing conditions previously reported to induce SigB (55, 56). While we did not observe altered LTA PAGE profiles for all conditions tested, LTA extracted from cells grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 10% NaCl or 30 mM KOH produced PAGE profiles diagnostic of modified LTA (Fig. 5). NaCl was thus chosen for further study. To assess the effects of high-salt stress induction over time on CsbB-GtcA-YfhO gene expression and the corresponding changes to LTA structure, a 4-h time course experiment was conducted after shock exposure to 10% NaCl (Fig. 6A). Strikingly, the loss of LTA band resolution intensified with increased time of NaCl exposure with discrete single banding disappearing as early as the 1-h time point. During this initial 1-h period, there was at most a single round of cell division. Based on these results, a large-scale S. aureus culture was grown in 10% NaCl to mimic the 4-h growth point and the purified LTA analyzed by 1H NMR (Fig. 6B). LTA was appreciably glycosylated with GlcNAc at 5.5% when extracted from cells cultured under NaCl cell envelope stress.

FIG 5.

PAGE of LTA samples extracted from wild-type TM226 grown under cell envelope stress-inducing conditions. LTA samples were extracted from cultures grown for approximately five generations under the indicated stress-inducing conditions. When subjected to growth in the presence of 10% NaCl or 30 mM KOH, single-band resolution was eliminated in comparison to the well-resolved bands present in the wild type.

FIG 6.

LTA modification and gene expression analysis of S. aureus TM226 grown in 10% NaCl-containing TSB medium. (A) LTA was harvested for PAGE at various time points. Single-band resolution of LTA is gradually lost as the high-salt exposure time is prolonged. (B) NMR spectra of LTA from wild-type TM226 grown in TSB supplemented with 10% NaCl. The GlcNAc composition of LTA increased to approximately 5.5%, while d-Ala decreased to 72.8%. (C) High-salt stress induces the expression of SigB-regulated genes, including the CsbB-GtcA genes, as measured by RT-qPCR.

Parallel time point culture aliquots were withdrawn and analyzed in tandem for gene expression by RT-qPCR (Fig. 6C). To gauge the extent of SigB activation, expression of both sigB and the known SigB regulated marker asp23 (54) were monitored. There was a sharp increase in both sigB and asp23 transcript levels at 5 min. Likewise, both csbB and gtcA were upregulated 8-fold and 2-fold at the same time point. Over time, the levels of all of these upregulated targets waned, although csbB expression levels remained somewhat elevated out to 4 h. In contrast, yfhO and dltB expression did not change throughout the time course of the experiment.

DISCUSSION

There is growing appreciation for the role and dynamic nature of LTA modifications in altering cellular function, and here we report the identification and preliminary characterization of genes from S. aureus involved in LTA glycosylation with GlcNAc residues. We demonstrate that the expression of both CsbB and YfhO is absolutely required to modify LTA with GlcNAc residues in a pathway that likely resembles other characterized three-component glycosylation systems (57). These glycoconjugate systems are widespread in bacteria, modifying O-antigens, lipid A, mycolylarabinogalactan, and other cell surface polymers in addition to TAs. Glycosylation involves a three component pathway similar to the prototype O-antigen glycosylation outlined for the Shigella flexneri serotype converting bacteriophage Sfx (41). First, a DPM1 (dolichol-phosphate mannose) family glycosyltransferase charges an undecaprenol lipid carrier with a sugar from an NDP-sugar donor to form a membrane-associated Und-P-sugar. The CsbB protein belongs to this family of enzymes and has a predicted topology consistent with the characteristic two C-terminal transmembrane α-helices. Next, the Und-P-sugar is transported to the outer leaflet of the cell membrane by a small integral membrane “flippase” typically possessing four transmembrane α-helices. In S. aureus, GtcA was identified as the most likely candidate for this role based on the predicted topology. Finally, a second glycosyltransferase belonging to the GT-C family then utilizes Und-P-sugar donor to glycosylate an acceptor molecule to form the product glycoconjugate. GT-C family enzymes share limited overall primary sequence homology but are generally multipass integral membrane proteins (8 to 13 transmembrane helices) with an active-site aspartate-containing motif in the first extracytoplasmic loop (58, 59). The candidate LTA α-O-GlcNAc transferase YfhO identified here possesses all of these characteristics.

Unlike most three component glycosylation systems, however, the genes for CsbB, GtcA, and YfhO are located at noncontiguous positions spread throughout the S. aureus chromosome. The lack of clustering with any TA-associated genes in S. aureus makes YfhO family glycosyltransferase substrate prediction challenging, particularly given the similarity in TA structure between type I poly-GroP LTA and poly-RboP WTA. In certain serovars of L. monocytogenes (31), YfhO is a WTA GlcNAcylating enzyme, while in S. aureus it is now clear that LTA is the preferred ligand. In the absence of any known TA discriminating amino acid sequence motifs, experimental characterization remains necessary. While both TA substrates are structurally similar phosphodiester linked alditol polymers, WTA and LTA have mechanistically distinct biosynthetic pathways (9, 10, 13). LTA is polymerized on the outer cell surface by the enzyme LtaS, which polymerizes GroP from phosphatidylglycerol donors (37, 60), while WTA is built from polymerization of RboP entirely within the cytoplasm (9). In this respect, LTA is more similar to Wzy-dependent O-antigen pathways whereby the polysaccharide is polymerized from building blocks on the extracellular surface, and WTA is more similar to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter pathways that extrude a polymer completed entirely within the cytoplasm. Mann et al. have demonstrated that the same three-component glycosylation system is capable of modifying both types of glycopolymer-forming systems (61), providing conceptual evidence for the mechanistic feasibility of a common GT-C family glycosyltransferase to modify preassembled (WTA) or surface-polymerized (LTA) glycopolymers using common machinery.

In contrast to S. aureus, where GlcNAcylated LTA is difficult to detect in most strains (10), many Bacillus spp. elaborate LTA richly substituted with GlcNAc modifications under standard culture conditions (62). An LTA glycosylation pathway using Und-P-sugar donor was originally proposed (62), which has been supported by recent work in B. subtilis proposing a three-component LTA GlcNAcylation system similar to the one described here in S. aureus (63). In B. subtilis, yfhO and csbB are cotranscribed in the same transcriptional unit that can be further induced by the extracytoplasmic sigma factor σX, as well as the alternative sigma factor σB (64, 65). These genes were thus suggested to be involved in modifying the cell envelope in response to stress possibly through glycosyl transferase activity, though their exact functions remained unclear at that time. Subsequent work in B. subtilis discovered that csbB expression in the absence of yfhO induced marked cell stress, likely due to Und carrier lipid sequestration as Und-P-sugar dead-end intermediates (66). While these studies are largely consistent with a common role for LTA glycosylation in both B. subtilis and S. aureus, there are clearly unique aspects to how the CsbB-GtcA-YfhO system functions in S. aureus. The most apparent difference is in the tightly repressed basal level of LTA GlcNAcylation, since less than 2% of the GroP units are modified with GlcNAc in the wild type (Fig. 2). Low expression of CsbB appears to dictate LTA GlcNAc levels in S. aureus. Regulatory control at the Und-P sugar loading step is a logical checkpoint, given the known toxicity of accumulating Und dead-end intermediates (6, 66, 67). By regulating flux into the three-component glycosylation pathway, no Und intermediates can accumulate and peptidoglycan/WTA assembly will not have to compete with a depleted pool of carrier. In contrast to CsbB, we observed basal YfhO expression under standard culture conditions in both SigB-positive (TM226) and SigB-defective (RN4220) genetic backgrounds and did not observe appreciable YfhO upregulation upon sigB overexpression or salt-induced cell envelope stress. Consistent with this result, other transcriptional profiling studies in S. aureus have not identified YfhO as a member of the SigB regulon. Both CsbB and the putative transporter GtcA, however, have SigB-driven promoters (50, 51, 68), and we were able to observe induction upon high-salt exposure (Fig. 6C). The tight basal regulation and transient induction under certain cell culture conditions is a satisfying explanation for variations in previous reports regarding LTA-GlcNAc levels in S. aureus. Since the genetic determinants CsbB-GtcA-YfhO identified here are distributed ubiquitously throughout the species, strain-specific LTA glycotypes are a less likely explanation.

The SigB regulon is the dominant alternate sigma factor responsible for mounting cell envelope stress response in S. aureus, controlling a variety of cell wall-related processes conferring antibiotic resistance and adaption to environmental stress (50, 54, 56). The LTA GlcNAc tailoring modification observed here presumably enables the bacteria to alter its cell wall physiology to tolerate such environmental challenges. Curiously, we did not observe LTA GlcNAcylation under all of the classical SigB stress-inducing conditions tested (Fig. 5). High-NaCl conditions and 30 mM KOH treatments were by far the most potent effectors, inducing a remarkably rapid phenotypic shift in the LTA PAGE profile (Fig. 5). Conversion was apparent after at most a single round of cell division had occurred (Fig. 6A). Once more, while we did observe robust induction of csbB within minutes of high-salt exposure and a decrease in d-Ala LTA content (Fig. 6B and C), we did not observe a coordinated transcriptional repression of the dlt operon, as previously reported for S. aureus and Lactobacillus casei when cultured in high-salt media (69, 70). The downregulation of dlt would help rationalize how such a rapid change in the LTA GlcNAcylation state could be achieved, particularly if the sole mechanism for switching to a GlcNAc-rich LTA is through dilution of unmodified mature LTA with a highly GlcNAcylated nascent polymer via cell division. This raises the intriguing possibility of GlcNAcylation of mature LTA already within the cell envelope prior to challenge with NaCl or KOH. For this to occur, existing d-Ala linkages would likely have to be removed since the two LTA modification systems are in competition for a shared poly-GroP substrate. Transcription-independent mechanisms that lower d-Ala LTA content have been proposed. Kiriukhin and others have demonstrated that high NaCl concentrations inhibit transacylation from d-alanyl-DltC to the C2-OH of GroP and stimulate hydrolytic cleavage of the d-alanyl thioester (23, 71). Alternatively, a recently described TA d-Ala esterase FmtA could play a role in reducing the LTA d-alanylation content under certain conditions (72). The mechanism of dealanylation by KOH treatment is more straightforward, as d-Ala LTA ester linkages are extremely labile to base. Regardless of the mechanism, modification of mature LTA chains would require reorientation so as to place the acceptor 2-OH of the GroP repeating unit within the putative active site of YfhO. The active site of GT-C family enzymes is likely within extracytoplasmic loop 1 at the membrane surface (58, 59). LTA conformation is highly dynamic, and biophysical studies have demonstrated a reversible transition from an extended conformation to a random coil that packs against the membrane surface in a high-NaCl solution (23, 73). It remains unknown, however, how GlcNAcylation impacts LTA structure and function, but the induction by cell envelope stress demonstrated here would suggest a net stabilizing affect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmid construction, and growth conditions.

All S. aureus strains used in this study are listed in Table 1 and are derived from the reference strain NCTC8325. Gene deletions were made with the E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector pKFC for allelic exchange using 1-kb flanking DNA homology arms amplified by PCR (33). TM852 was generated using pKFC with the dltC::Kanr cassette from SHM084. Plasmid assemblies were performed using an In-Fusion cloning kit (Clontech). S. aureus was typically grown in TSB at 37°C with agitation. Where necessary, antibiotic markers were selected with chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml), erythromycin (10 μg/ml), or a combination of kanamycin and neomycin (25 μg/ml each). The strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| RN4220 | Kreiswirth et al. (74) | |

| TM226 | S. aureus HG003 ϕ11::FRT | Santiago et al. (75) |

| SHM084 | S. aureus Newman dltC::Kanr | S. Walker, Harvard Medical School (unpublished data) |

| TM684 | RN4220(PcadcsbB-gtcA) | This study |

| KK713 | RN4220 tarO::Tetr | This study |

| KK717 | RN4220 tarO::Tetr(PcadcsbB-gtcA) | This study |

| KK731 | RN4220 ΔSA664 (tarM) | This study |

| KK737 | RN4220 ΔyfhO | This study |

| KK739 | RN4220 ΔSA228 (tarS) | This study |

| KK742 | RN4220 ΔtarM ΔtarS | This study |

| KK753 | RN4220 ΔyfhO(PcadcsbB-gtcA) | This study |

| KK776 | RN4220(PcadcsbB) | This study |

| KK777 | RN4220(PcadgtcA) | This study |

| KK791 | RN4220(pLI50, PcadcsbB-gtcA, PcadyfhO) | This study |

| TM852 | RN4220 dltC::Kanr | This study |

| KK860 | RN4220(PcadyfhO) | This study |

| TM864 | RN4220(PspAsigB) | This study |

| KK868 | RN4220 dltC::Kanr(PcadcsbB-gtcA, PcadyfhO) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKFC | E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector for cloning and allelic exchange; Carbr (E. coli), Cmr (S. aureus) | Kato and Sugai (33) |

| pLI50 | E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector; Carbr (E. coli), Cmr (S. aureus) | Lee et al. (76) |

| pLI50 PcadC | pLI50 with Pcad cadC for cadmium-inducible expression; Carbr (E. coli), Cmr (S. aureus) | This study |

| pCN59 | E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector, Pcad cadC blaZ transcriptional terminator; Carbr (E. coli), Apr (S. aureus), Emr (S. aureus) | Charpentier et al. (77) |

| PspAsigB | pLI50 with protein A (spa) promoter for constitutive gene expression; Carbr (E. coli), Cmr (S. aureus) | This study |

| PcadcsbB-gtcA | pLI50 PcadC cadC expressing both SAOUHSC_00713 and SAOUHSC_002722 | This study |

| PcadyfhO | pCN59 expressing SAOUHSC_01213 | This study |

| PcadcsbB | pLI50 PcadC expressing SAOUHSC_00713 | This study |

| PcadgtcA | pLI50 PcadC expressing SAOUHSC_002722 | This study |

All S. aureus strains are derivatives of the reference strain NCTC8325. Phenotypes: Kanr, kanamycin and neomycin resistance; Carbr, carbenicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Emr, erythromycin resistance; Apr, apramycin resistance.

WTA extraction.

WTA was isolated as previously described (34). Briefly, 20 ml of stationary-phase S. aureus was pelleted, washed with 30 ml of buffer 1 [50 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), pH 6.5] and resuspended in 30 ml of buffer 2 (50 mM MES, 4% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). Samples were placed in a boiling water bath for 1 h and pelleted. Cell wall sacculus was resuspended in buffer 2, transferred to a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube, and pelleted by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 1 min). The cells were washed consecutively with buffer 2, buffer 3 (50 mM MES [pH 6.5], 2% NaCl), and then finally with buffer 1. The pellet was then resuspended in 1 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–0.5% (wt/vol) SDS containing 20 μg of proteinase K, followed by incubation at 50°C for 4 h on a shaking heat block. Samples were then washed once with buffer 3 and three times with MilliQ distilled H2O (dH2O) to remove SDS before being thoroughly resuspended in 1 ml of 0.1 M NaOH. Hydrolysis was performed at room temperature for 16 h with constant agitation before neutralization with 250 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.8). Insoluble cell wall debris was removed by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 1 min), and the WTA-containing supernatant was extracted into a clean tube.

TA-PAGE.

For PAGE analysis of both WTA and LTA, a separating gel (20%T, 6%C) and stacking (3%T, 0.26%C) was cast using a Bio-Rad Protein II xi system (20 cm by 16 cm by 0.75 mm) as previously described (34). Crude extracts were diluted 1:3 in loading buffer (50% glycerol in running buffer with a trace of bromophenol blue) to a maximum sample volume of 15 μl. The gel was developed at 4°C with a constant current of 40 mA per gel for approximately 18 to 20 h in Tris-Tricine running buffer (0.1 M Tris, 0.1 M Tricine [pH 8.2]). Gels were then stained with alcian blue (1 mg/ml, 3% acetic acid), followed by silver staining, according to established protocols (35).

LTA purification.

LTA was purified using the 1-butanol extraction method as described elsewhere (36, 37). A 20-ml TSB starter culture was grown until mid-log phase and used to inoculate 4 liters of TSB. After overnight incubation, stationary-phase cells were pelleted and washed with 100 ml of resuspension buffer (50 mM sodium citrate [pH 4.7]). Washed cells were kept cool and disrupted by bead beating with zirconia-silica beads (0.1-mm-diameter beads; four 2.5-min pulses; BioSpec Products BeadBeater). Cell envelope components were collected by centrifugation (30,000 × g, 1 h) and resuspended in 70 ml of resuspension buffer, to which 50 ml of 1-butanol was added. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 45 min with shaking and then centrifuged (30,000 × g, 1 h) to remove insoluble material and induce phase separation. The lower aqueous phase was lyophilized and resuspended in 5 ml of equilibration buffer (15% 1-propanol in 50 mM citrate [pH 4.7]). The crude lysate was centrifuged (20,000 × g, 10 min) and filtered (0.22-μm pore size) to remove residual debris. The clarified supernatant was then subjected to hydrophobic interaction chromatography on a HiPrep Octyl 4FF (16/10) column (GE Healthcare) and LTA eluted with a linear gradient of 15 to 60% 1-propanol in 50 mM citrate (pH 4.7). Fractions were analyzed for phosphate content by colorimetric molybdate assay (38). Briefly, 100 μl of each fraction was combined with 200 μl of ashing solution (2 M H2SO4, 0.44 M HClO4) and incubated uncapped at 120°C for 3 h in a fume hood. Then, 1 ml of reducing solution (3 mM ammonium molybdate, 0.25 M sodium acetate, 1% ascorbic acid) was added, followed by incubation in a 45°C water bath for 2 h with occasional mixing. Subsequently, 250 μl of each fraction was transferred to a 96-well plate and read at 700 nm. Phosphate-containing fractions were combined, dried on a rotary evaporator, and dissolved in 5 ml of MilliQ dH2O for extensive dialysis using cellulose ester dialysis membranes (molecular mass cutoff, 0.5 to 1.0 kDa; Spectrum Labs). The dialysate was lyophilized in a preweighed vial to determine LTA yield (typically 5 to 15 mg per 4 liters of culture) and stored at −20°C.

1H NMR.

Purified LTA was deuterium exchanged by two rounds of lyophilization using 500 μl of 99.8% D2O. LTA was then resuspended in 550 μl of 99.9% D2O for NMR analysis using a Bruker Avance III 600 at 298K with water presaturation, a 10-ppm spectral width, a 5.45-s acquisition time, a 5-s recycle delay, a 0.3-Hz line broadening, and 512 scans. The collected spectra were analyzed and quantified using Bruker TopSpin 3.5. The chemical shifts assigned to each LTA component were integrated and adjusted for the number of protons, as described previously (36). Briefly, the GlcNAc anomeric and acetate integrals were averaged for four protons (GlcNAcav.). The integral between 3.7 and 4.2 ppm was added to the Gro-3-CH integral, and the underlying GlcNAc resonances (5H) were deducted to obtain the total amount of glycerol (5H+). Average LTA chain lengths were estimated by determining the ratio of glycerol (5H+) to CH2+CH3 (average, 58H+) of the lipid chains, the levels of d-Ala modification by the ratio of d-Ala-αH to glycerol (5H+) and, similarly, the level of GlcNAc modification by the ratio of GlcNAcav. to glycerol (5H+). Standard deviations were calculated from at least two experimental repetitions.

Small-scale LTA extraction for PAGE.

Either 20 ml of stationary-phase cells or 10 optical density units/ml of exponentially growing cells were pelleted and washed once with 2 ml of resuspension buffer (50 mM sodium citrate [pH 4.7]). The cells were disrupted on a MagNA Lyser (Roche) with four 30-s pulses (7,000 rpm), and the cell envelope fragments were pelleted (20,000 × g, 4°C, 1 h). Pellets were resuspended in 350 μl of resuspension buffer, and an equal volume of 1-butanol was added. The extraction was carried out on a shaking heat block at 37°C for 45 min. The crude extract was centrifuged (20,000 × g, 4°C, 1 h) to pellet insoluble materials, and the lower aqueous phase was then extracted into a clean tube.

For PAGE analysis, LTA was first enzymatically deacylated with lipase. For the butanol aqueous-phase crude extract, 50 μl of the aqueous layer was combined with 50 μl of 50 mM Tris (free base) and then adjusted to pH 8.5 with 2 μl of 1 M NaOH. For column-purified LTA, samples were dissolved to 5 μg/μl in 100 μl of 10 mM Tris (pH 8.5). For both crude and purified LTA, deacylation was carried out by adding 1 μl of Resinase HT, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 50°C for 16 h. Lipase-treated samples were then analyzed by PAGE and stained as described above.

Dephosphorylation of LTA.

LTA was monomerized by dephosphorylation with hydrofluoric acid. Approximately 1 mg of purified LTA was resuspended in 100 μl of 47% HF and incubated at room temperature for 20 h. HF was then evaporated in a closed vessel with a stream of filtered air until there was no residual liquid using a KOH pellet trap with the outlet tubing inserted into a saturated base solution. Dried samples were resuspended in 200 μl of 5 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and the pH was adjusted to 7 with dilute ammonium hydroxide before lyophilization.

ESI-MS.

MS analysis was performed on a Waters Q-TOF Premier quadrupole/time of flight mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation [Micromass, Ltd.], Manchester, UK). Operation of the mass spectrometer was performed using MassLynx software version 4.1 (Waters). Samples were introduced into the mass spectrometer using a Waters 2695 high-performance liquid chromatograph. The samples were analyzed using flow injection analysis. The mobile phase consisted of 50% acetonitrile (LC-MS grade) and 50% aqueous 10 mM ammonium acetate with a flow rate of 0.15 ml/min. The nitrogen drying gas temperature was set to 300°C at a flow of 7 liters/min with a capillary voltage of 2.8 kV. The mass spectrometer was set to scan from 100 to 1,000 m/z in positive- and negative-ion modes, using ESI.

Cell envelope stress response induction.

For stress-inducing conditions, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 into prewarmed TSB at 37°C. Upon reaching an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.2, cultures were diluted 10-fold into prewarmed TSB with final concentrations of 7% ethanol (EtOH), 10% NaCl, 30 mM KOH, 1 mM MnCl2, or 0.006% Tween 20. Cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.5, and 20 ml was harvested for small-scale LTA extraction as detailed above. A second 1-OD unit/ml equivalent of the cell aliquot was rapidly pelleted and resuspended in 1 ml of RNAlater (Applied Biosystems). Pelleted cells were stored at −20°C before RNA extraction for RT-qPCR.

RT-qPCR.

RNA was extracted using the SurePrep TrueTotal RNA purification kit (Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's protocol with modifications. To facilitate S. aureus lysis, the lysozyme digestion solution was supplemented with 13 μg of lysostaphin. The on-column DNase I digestion was performed using 2 U of DNase I (RNase-free; NEB). Upon elution, RNA was treated again with 2 U of DNase I in a 100-μl reaction at 37°C for 15 min. Total RNA was cleaned by a second column purification. RNA integrity was assessed by morpholinepropanesulfonic acid-formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by determining the absorbance at 260 nm. Synthesis of cDNA was carried out using a Maxima first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo), while real-time qPCRs were performed using PowerUP SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems) on an AriaMX real-time PCR system (Agilent). Data analysis was performed using the accompanying software. Primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were designed and validated according to MIQE guidelines (39).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gloria Komazin for help with cloning and strain construction (Pennsylvania State University), Tapas Mal, Carlos Pacheco, and Debashish Sahu (Penn State NMR Facility, University Park, PA) for expert technical assistance with NMR, James R. Miller for expert technical assistance with ESI-MS (Penn State Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Core Facility, University Park, PA), and Suzanne Walker for strains TM226 and SHM084.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00017-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otto M. 2010. Staphylococcus colonization of the skin and antimicrobial peptides. Expert Rev Dermatol 5:183–195. doi: 10.1586/edm.10.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong SYC, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG. 2015. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zapun A, Contreras-Martel C, Vernet T. 2008. Penicillin-binding proteins and β-lactam resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:361–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sewell EWC, Brown ED. 2014. Taking aim at wall teichoic acid synthesis: new biology and new leads for antibiotics. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 67:43–51. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weidenmaier C, Peschel A. 2008. Teichoic acids and related cell wall glycopolymers in Gram-positive physiology and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:276–287. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swoboda JG, Meredith TC, Campbell J, Brown S, Suzuki T, Bollenbach T, Malhowski AJ, Kishony R, Gilmore MS, Walker S. 2009. Discovery of a small molecule that blocks wall teichoic acid biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Chem Biol 4:875–883. doi: 10.1021/cb900151k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquina L, Santa Maria JP, McKay Wood B, Moussa SH, Matano LM, Santiago M, Martin SES, Lee W, Meredith TC, Walker S. 2016. A synthetic lethal approach for compound and target identification in Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Chem Biol 12:40–45. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. 2010. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000414. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown S, Santa Maria JP, Walker S. 2013. Wall teichoic acids of gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 67:313–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Percy MG, Gründling A. 2014. Lipoteichoic acid synthesis and function in gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:81–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091213-112949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duckworth M, Archibald AR, Baddiley J. 1975. Lipoteichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid carrier in Staphylococcus aureus H. FEBS Lett 53:176–179. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gründling A, Schneewind O. 2007. Genes required for glycolipid synthesis and lipoteichoic acid anchoring in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 189:2521–2530. doi: 10.1128/JB.01683-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneewind O, Missiakas D. 2014. Lipoteichoic acids, phosphate-containing polymers in the envelope of gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol 196:1133–1142. doi: 10.1128/JB.01155-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schirner K, Marles-Wright J, Lewis RJ, Errington J. 2009. Distinct and essential morphogenic functions for wall- and lipo-teichoic acids in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J 28:830–842. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oku Y, Kurokawa K, Matsuo M, Yamada S, Lee BL, Sekimizu K. 2009. Pleiotropic roles of polyglycerolphosphate synthase of lipoteichoic acid in growth of Staphylococcus aureus cells. J Bacteriol 91:141–151. doi: 10.1128/JB.01221-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peschel A, Vuong C, Otto M, Gotz F. 2000. The d-alanine residues of Staphylococcus aureus teichoic acids alter the susceptibility to vancomycin and the activity of autolytic enzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:2845–2847. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.10.2845-2847.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atilano ML, Pereira PM, Yates J, Reed P, Veiga H, Pinho MG, Filipe SR. 2010. Teichoic acids are temporal and spatial regulators of peptidoglycan cross-linking in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:18991–18996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004304107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mechler L, Bonetti E-J, Reichert S, Flötenmeyer M, Schrenzel J, Bertram R, François P, Götz F. 2016. Daptomycin tolerance in the Staphylococcus aureus pitA6 mutant is due to upregulation of the dlt operon. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2684–2691. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03022-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvalho F, Atilano ML, Pombinho R, Covas G, Gallo RL, Filipe SR, Sousa S, Cabanes D. 2015. l-Rhamnosylation of Listeria monocytogenes wall teichoic acids promotes resistance to antimicrobial peptides by delaying interaction with the membrane. PLoS Pathog 11:1–29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peschel A, Otto M, Jack RW, Kalbacher H, Jung G, Götz F. 1999. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J Biol Chem 274:8405–8410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovács M, Halfmann A, Fedtke I, Heintz M, Peschel A, Vollmer W, Hakenbeck R, Brückner R. 2006. A functional dlt operon, encoding proteins required for incorporation of d-alanine in teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria, confers resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol 188:5797–5805. doi: 10.1128/JB.00336-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perego M, Glaser P, Minutello A, Strauch MA, Leopold K, Fischer W. 1995. Incorporation of d-alanine into lipoteichoic acid and wall teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis: identification of genes and regulation. J Biol Chem 270:15598–15606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuhaus FC, Baddiley J. 2003. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of d-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:686–723. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.686-723.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia G, Maier L, Sanchez-Carballo P, Li M, Otto M, Holst O, Peschel A. 2010. Glycosylation of wall teichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus by TarM. J Biol Chem 285:13405–13415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobhanifar S, Worrall LJ, Gruninger RJ, Wasney GA, Blaukopf M, Baumann L, Lameignere E, Solomonson M, Brown ED, Withers SG, Strynadka NCJ. 2015. Structure and mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus TarM, the wall teichoic acid α-glycosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E576–E585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418084112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobhanifar S, Worrall LJ, King DT, Wasney GA, Baumann L, Gale RT, Nosella M, Brown ED, Withers SG, Strynadka NCJ. 2016. Structure and mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus TarS, the wall teichoic acid β-glycosyltransferase involved in methicillin resistance. PLoS Pathog 12:e1006067. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown S, Xia G, Luhachack LG, Campbell J, Meredith TC, Chen C, Winstel V, Gekeler C, Irazoqui JE, Peschel A, Walker S. 2012. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus requires glycosylated wall teichoic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:18909–18914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209126109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winstel V, Xia G, Peschel A. 2014. Pathways and roles of wall teichoic acid glycosylation in Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Med Microbiol 304:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winstel V, Kühner P, Salomon F, Larsen J, Skov R, Hoffmann W, Peschel A, Weidenmaier C. 2015. Wall teichoic acid glycosylation governs Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization. mBio 6:e00632-. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00632-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allison SE, D'Elia MA, Arar S, Monteiro MA, Brown ED. 2011. Studies of the genetics, function, and kinetic mechanism of TagE, the wall teichoic acid glycosyltransferase in Bacillus subtilis 168. J Biol Chem 286:23708–23716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.241265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eugster MR, Morax LS, Hüls VJ, Huwiler SG, Leclercq A, Lecuit M, Loessner MJ. 2015. Bacteriophage predation promotes serovar diversification in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 97:33–46. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spears PA, Havell EA, Hamrick TS, Goforth JB, Levine AL, Abraham ST, Heiss C, Azadi P, Orndorff PE. 2016. Listeria monocytogenes wall teichoic acid decoration in virulence and cell-to-cell spread. Mol Microbiol 101:714–730. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato F, Sugai M. 2011. A simple method of markerless gene deletion in Staphylococcus aureus. J Microbiol Methods 87:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meredith TC, Swoboda JG, Walker S. 2008. Late-stage polyribitol phosphate wall teichoic acid biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 190:3046–3056. doi: 10.1128/JB.01880-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolters PJ, Hildebrandt KM, Dickie JP, Anderson JS. 1990. Polymer length of teichuronic acid released from cell walls of Micrococcus luteus. J Bacteriol 172:5154–5159. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5154-5159.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morath S, Geyer A, Hartung T. 2001. Structure–function relationship of cytokine induction by lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus. J Exp Med 193:393–398. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gründling A, Schneewind O. 2007. Synthesis of glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:8478–8483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701821104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Draing C, Pfitzenmaier M, Zummo S, Mancuso G, Geyer A, Hartung T, Von Aulock S. 2006. Comparison of lipoteichoic acid from different serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Biol Chem 281:33849–33859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. 2009. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mann E, Whitfield C. 2016. A widespread three-component mechanism for the periplasmic modification of bacterial glycoconjugates. Can J Chem 94:883–893. doi: 10.1139/cjc-2015-0594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guan S, Bastin DA, Verma NK. 1999. Functional analysis of the O antigen glucosylation gene cluster of Shigella flexneri bacteriophage SfX. Microbiology 145:1263–1273. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Percy MG, Karinou E, Webb AJ, Gründling A. 2016. Identification of a lipoteichoic acid glycosyltransferase enzyme reveals that GW-domain-containing proteins can be retained in the cell wall of Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of lipoteichoic acid or its modifications. J Bacteriol 198:2029–2042. doi: 10.1128/JB.00116-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arakawa H, Shimada A, Ishimoto N, Ito E. 1981. Occurrence of ribitol-containing lipoteichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus h and its glycosylation. J Biochem 89:1555–1563. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maurer JJ, Mattingly SJ. 1991. Molecular analysis of lipoteichoic acid from Streptococcus agalactiae. J Bacteriol 173:487–494. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.487-494.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vergara-Irigaray M, Maira-Litran T, Merino N, Pier GB, Penades JR, Lasa I. 2008. Wall teichoic acids are dispensable for anchoring the PNAG exopolysaccharide to the Staphylococcus aureus cell surface. Microbiology 154:865–877. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/013292-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maira-Litran T, Kropec A, Goldmann D, Pier GB. 2004. Biologic properties and vaccine potential of the staphylococcal poly-N-acetyl glucosamine surface polysaccharide. Vaccine 22:872–879. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Gara JP. 2007. ica and beyond: biofilm mechanisms and regulation in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 270:179–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen Y, Boulos S, Sumrall E, Gerber B, Julian-Rodero A, Eugster MR, Fieseler L, Nyström L, Ebert MO, Loessner MJ. 2017. Structural and functional diversity in Listeria cell wall teichoic acids. J Biol Chem 292:17832–17844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.813964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eugster MR, Loessner MJ. 2011. Rapid analysis of Listeria monocytogenes cell wall teichoic acid carbohydrates by ESI-MS/MS. PLoS One 6:e21500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bischoff M, Dunman P, Kormanec J, Macapagal D, Murphy E, Mounts W, Berger-Bachi B, Projan S. 2004. Micro of the Staphylococcus aureus B regulon. J Bacteriol 186:4085–4099. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4085-4099.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mäder U, Nicolas P, Depke M, Pané-Farré J, Debarbouille M, van der Kooi-Pol MM, Guérin C, Dérozier S, Hiron A, Jarmer H, Leduc A, Michalik S, Reilman E, Schaffer M, Schmidt F, Bessières P, Noirot P, Hecker M, Msadek T, Völker U, van Dijl JM. 2016. Staphylococcus aureus transcriptome architecture: from laboratory to infection-mimicking conditions. PLoS Genet 12:e1005962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kullik I, Giachino P, Fuchs T. 1998. Deletion of the alternative sigma factor in Staphylococcus aureus reveals its function as a global regulator of virulence genes. J Bacteriol 180:4814–4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morikawa K, Maruyama A, Inose Y, Higashide M, Hayashi H, Ohta T. 2001. Overexpression of sigma factor, σB, urges Staphylococcus aureus to thicken the cell wall and to resist β-lactams. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 288:385–389. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giachino P, Engelmann S, Bischoff M. 2001. SigB activity depends on RsbU in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 183:1843–1852. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.6.1843-1852.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knobloch JKM, Bartscht K, Sabottke A, Rohde H, Feucht HH, Mack D. 2001. Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis depends on functional RsbU, an activator of the sigB operon: differential activation mechanisms due to ethanol and salt stress. J Bacteriol 183:2624–2633. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2624-2633.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pané-Farré J, Jonas B, Förstner K, Engelmann S, Hecker M. 2006. The σB regulon in Staphylococcus aureus and its regulation. Int J Med Microbiol 296:237–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tytgat HLP, Lebeer S. 2014. The sweet tooth of bacteria: common themes in bacterial glycoconjugates. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 78:372–417. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lairson LL, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, Withers SG. 2008. Glycosyltransferases: structures, functions, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biochem 77:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061005.092322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liang D-M, Liu J-H, Wu H, Wang B-B, Zhu H-J, Qiao J-J. 2015. Glycosyltransferases: mechanisms and applications in natural product development. Chem Soc Rev 44:8350–8374. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00600G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vickery CR, Wood BM, Morris HG, Losick R, Walker S. 2018. Reconstitution of S. aureus lipoteichoic acid synthase activity identifies Congo red as a selective inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc 140:876–879. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b11704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mann E, Ovchinnikova OG, King JD, Whitfield C. 2015. Bacteriophage-mediated glucosylation can modify lipopolysaccharide O-antigens synthesized by an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-dependent assembly mechanism. J Biol Chem 290:25561–25570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.660803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iwasaki H, Shimada A, Yokoyama K, Ito E. 1989. Structure and glycosylation of lipoteichoic acids in Bacillus strains. J Bacteriol 171:424–429. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.424-429.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rismondo J, Percy MG, Gründling A. 2018. Discovery of genes required for lipoteichoic acid glycosylation predicts two distinct mechanism for wall teichoic acid glycosylation. J Biol Chem 293:3293–3306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akbar S, Price CW. 1996. Isolation and characterization of csbB, a gene controlled by Bacillus subtilis general stress transcription factor σB. Gene 177:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cao M, Helmann JD. 2004. The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function sX factor regulates modification of the cell envelope and resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. J Bacteriol 186:1136–1146. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1136-1146.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Inoue H, Suzuki D, Asai K. 2013. A putative bactoprenol glycosyltransferase, CsbB, in Bacillus subtilis activates SigM in the absence of cotranscribed YfhO. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 436:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.D'Elia MA, Pereira MP, Chung YS, Zhao W, Chau A, Kenney TJ, Sulavik MC, Black TA, Brown ED. 2006. Lesions in teichoic acid biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus lead to a lethal gain of function in the otherwise dispensable pathway. J Bacteriol 188:4183–4189. doi: 10.1128/JB.00197-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruhland GJ, Fiedler F. 1990. Occurrence and structure of lipoteichoic acids in the genus Staphylococcus. Arch Microbiol 154:375–379. doi: 10.1007/BF00276534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koprivnjak T, Mlakar V, Swanson L, Fournier B, Peschel A, Weiss JP. 2006. Cation-induced transcriptional regulation of the dlt operon of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 188:3622–3630. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3622-3630.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palomino MM, Allievi MC, Gründling A, Sanchez-Rivas C, Ruzal SM. 2013. Osmotic stress adaptation in Lactobacillus casei BL23 leads to structural changes in the cell wall polymer lipoteichoic acid. Microbiology 159:2416–2426. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.070607-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kiriukhin MY, Neuhaus FC. 2001. d-Alanylation of lipoteichoic acid: role of the d-alanyl carrier protein in acylation. J Bacteriol 183:2051–2058. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.6.2051-2058.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rahman MM, Hunter HN, Prova S, Verma V, Qamar A, Golemi-Kotra D. 2016. The Staphylococcus aureus methicillin resistance factor FmtA is a d-amino esterase that acts on teichoic acids. mBio 7:e02070-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02070-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gutberlet T, Frank J, Bradaczek H, Fischer W. 1997. Effect of lipoteichoic acid on thermotropic membrane properties. J Bacteriol 179:2879–2883. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2879-2883.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kreiswirth BN, Löfdahl S, Betley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Santiago M, Matano LM, Moussa SH, Gilmore MS, Walker S, Meredith TC. 2015. A new platform for ultra-high density Staphylococcus aureus transposon libraries. BMC Genomics 16:252. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee CY, Buranen SL, Zhi-Hai Y. 1991. Construction of single-copy integration vectors for Staphylococcus aureus. Gene 103:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Charpentier E, Anton AI, Barry P, Alfonso B, Fang Y, Novick RP. 2004. Novel cassette-based shuttle vector system for gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:6076–6085. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6076-6085.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.