Abstract

Objective

To explore stable and functional microRNA (miRNA)–disease relationships using a genome-wide expression profile pattern matching strategy.

Methods

We applied the ranked microarray pattern matching strategy Gene Set Enrichment Analysis to identify miRNA permutations with similar expression patterns to diseases. We also used quantitative reverse transcription PCR to validate the predicted expression levels of miRNAs in three diseases: inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), oesophageal cancer, and colorectal cancer.

Results

We found that hsa-miR-200 c was upregulated more than 40-fold in oesophageal cancer. The expression of miR-16 and miR-124 was not consistently upregulated in IBD or colorectal cancer.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that this expression profile matching strategy can be used to identify functional miRNA–disease relationships.

Keywords: microRNA, genome-wide expression pattern, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of single-stranded small noncoding RNAs (∼22 nucleotides long) that negatively regulate messenger RNA (mRNA) expression at the post-transcriptional level.1,2 miRNAs bind to the 3′-untranslated region of target genes through base-pairing, resulting in mRNA degradation and/or translational inhibition.3 Accumulating evidence shows that miRNAs are involved in multiple biological processes and cellular signalling pathways,4,5 and that mutations or the dysregulation of miRNAs can cause various diseases. Recently, several studies have identified close relationships between miRNAs and disease,4,6–9 leading to the construction of dozens of miRNA-related databases. For example, miR2Disease, a resource of miRNAs that are dysregulated in human diseases, currently includes 3273 miRNA–disease relationship entries.10

A common strategy to explore potential disease-related miRNAs is to identify miRNAs that are differentially expressed in a disease state using technologies such as quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR, miRNA microarray analysis, or small RNA deep sequencing. Alternatively, cell transcriptional responses to various treatments or perturbations can be compared using algorithms such as Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)11 and large gene expression profiling datasets to quantitatively calculate the relevance of different perturbations. The first large-scale effort to apply this principle was the Connectivity Map project, which aimed to find potential connections among molecule treatments, disease states, and other bioprocesses by querying large-scale expression profiling data and validated gene sets.12 Since then, several studies have also demonstrated the feasibility of this approach in drug reposition studies.13–15

Hypothetically, because miRNAs are integrated into regulatory networks that influence target and other downstream genes, cell transcriptional responses against miRNA perturbations (either overexpression or knockdown) may reflect the transcriptional response of the related disease state to some extent. Thus, miRNA–disease relationships can be identified using this transcriptional response comparison strategy. Previously, Jiang et al. suggested that it might be possible to determine miRNA–drug links by integrating miRNA targets with the expression profiles of cancers and cell responses to small molecules.16 However, to the best of our knowledge, no investigation has directly compared the transcriptional responses induced by both miRNA genotype variation and disease. Recently, our group developed the ExpTreeDB database, which allows users to mine relationships among manually curated perturbations such as agent treatment, genotype variation, disease state, stress, and infection.17 In this study, we explored miRNA–disease relationships using this methodology and datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). We collected global transcriptional response datasets representing 40 human diseases and 30 miRNA variation treatments. Pair-wise similarities were calculated to identify putative miRNA–disease links for a literature investigation and experimental validation in three diseases: inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), oesophageal cancer, and colorectal cancer. We found that miR-200 c was significantly overexpressed in oesophageal cancer. However, we did not observe the consistently upregulated expression of miR-16 or miR-124 in IBD or colorectal cancer.

Methods

Specimens

Subjects in this study were recruited by Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, and included five oesophageal cancer patients (four men and one woman; average age, 67 years), five colorectal cancer patients (three men and two women; average age, 62 years), and five IBD patients (two Crohn’s disease cases and three ulcerative colitis cases; four women and one man; average age, 38 years). The diagnosis of all patients had been confirmed by pathology. Patients with cancer were free of other malignant neoplasms, and had not undergone radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

This work was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital (approval number: 2014KY059). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to their participation.

Two 1×1 cm tissue samples and the 5 cm margin of each carcinoma sample were obtained during surgical resection. All samples were washed with saline solution then immediately placed into 2 ml RNAlater solution and stored at 4℃ overnight (>16h). The tissues were then stored at −80℃ until required for analysis. Tissue samples from IBD and corresponding normal tissues were collected during pretreatment endoscopic biopsies and prepared as described above.

RNA isolation from clinical tissues

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Tissues were centrifuged at 2000 rpm, speed 500 xg for 5 min, then cell pellets were homogenized in 1.0 ml TRIzol reagent and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Each sample was treated with 200 µl of chloroform, repeatedly inverted for 15 s, then incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,800 rpm for 10 min at 4℃, and the colourless supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and treated with the same volume of isopropyl alcohol. After incubation at 4℃ for 10 min, samples were again centrifuged at 12,800 rpm for 10 min at 4℃, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed with 75% ethanol. Samples were centrifuged twice at 11,800 rpm for 5 min at 4℃, with removal of the supernatant after the first centrifugation, then the pellet was dried at room temperature and dissolved in RNase-free water. The RNA concentration was quantified by a Nanodrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

qRT-PCR

cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). Briefly, 10 -µl reverse transcription reactions contained 2 nM miRNA RT primers, 500 µM dNTPs, 0.2 µl M-MLV reverse transcriptase, and 1 µg total RNA. Conditions were as follows: 16℃ for 30 min followed by 42℃ for 1 h and 75℃ for 10 min. The real-time PCR system contained 10 µl SYBR Premix Ex Taq, 0.5 µl upstream primer, 0.5 µl downstream primer (2.5 µM), 1 µl cDNA, and 8 µl RNase-free H2O. The reaction was incubated at 95℃ for 30 s, followed by 45 cycles of 95℃ for 5 s, then 60℃ for 30 s. miRNA expression was analysed using the 2 −ΔΔCt method, and U6 was selected as the control gene. Primer sequences are shown in Table S1. SPSS 17.0 software was used to perform statistical analysis. Data were shown as the mean ± SD. The t-test was used for analysis between cancer tissue and adjacent normal tissue or between disease and control group. Significance was defined as P value < 0.05.

Gene expression profiling data collection

We downloaded human global gene expression profiles representing transcriptional responses to miRNA perturbations and disease states from GEO dataset (GDS) records produced by two platforms, the Affymetrix human genome U133 plus 2.0 array (GPL570) and the Affymetrix human genome U133A array (GPL96). These two human microarray platforms are the most frequently used in GEO and include over 20,000 genes, which is favourable for use with the GSEA algorithm.12,13,18,19 Human GDS records with a “disease state” subtype description were downloaded as disease state datasets and were manually examined in ExpTreeDB.17 Datasets related to miRNA perturbations were downloaded from GEO series (GSE) resources, and detailed treatments as well as miRNA entries were manually extracted. A similar approach was used to obtain small RNA silencing datasets. We required that one gene expression profile related to a given perturbation must include a blank control group so that transcriptional responses to perturbations could be clearly defined.

Generating a ranked gene list

Within each GEO dataset, we manually selected the experimental group of a particular perturbation. The experimental groups were then manually matched to normal control groups. Specific genotype variations and disease states were defined as “perturbations” to cells that induce transcriptional responses. Following the approach used in ExpTreeDB,17 we generated a phenotype ranked list (PRL) to denote the transcriptional response to a perturbation such as miRNA overexpression, gene silencing, or disease state. In brief, pair-wise global gene expression fold-changes were calculated, and all fold-change lists under a certain perturbation were merged into a PRL using a hierarchical majority voting scheme to prevent poor representation of heterogeneous experimental settings.20 Thus, the genes showing the highest level of up/down-regulation (presented as microarray probe names) under each permutation were placed at the top/bottom of the corresponding PRL.

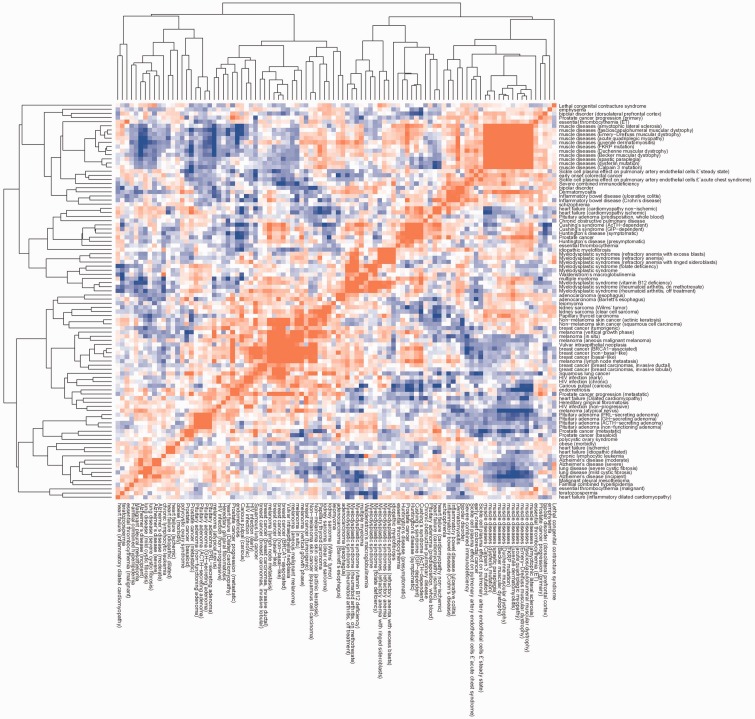

For the disease state, two perturbations were defined to a different extent: a description of the disease, such as IBD, and the provision of more detailed information about stage or subtype, such as ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD). We generated PRLs for both definitions, and correlation calculations showed that the two PRLs had high correlation coefficients (Enrichment Score = 0.662, Figure 1). Therefore, in this study we employed a general description of disease states and perturbation definitions (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A heat map of classified disease correlation scores. Each permutation is represented by a phenotype ranked list where the genes showing the most up-regulation are placed at the top while the most down-regulated genes are at the bottom. The correlation scores were computed by measuring gene regulation in correspondence with the GSEA method to obtain a score from −1 to +1. The color scale shows positive correlations in red and negative correlations in blue.

Table 1.

Data sets used in this study.

| Type | Term | Accession no. | Cell type or disease state pair |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease state | Adenocarcinoma (oesophagus) | GDS1321 | Barrett’s oesophagus/normal |

| adenocarcinoma/normal | |||

| Alzheimer’s disease | GDS810 | moderate AD/control | |

| severe AD/control | |||

| incipient AD/control | |||

| Bipolar disorder | GDS2190 | bipolar disorder/control | |

| GDS2191 | bipolar disorder/control | ||

| Breast cancer | GDS2250 | basal-like cancer/normal | |

| GDS2617 | non-basal-like cancer/normal | ||

| BRCA1-associated cancer/normal | |||

| tumorigenic cancer cell/normal | |||

| GDS2635 | invasive lobular carcinoma/lobular control | ||

| invasive ductal carcinoma/lobular control | |||

| Carious pulpal | GDS1850 | carious/healthy | |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia | GDS2643 | Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia/normal | |

| chronic lymphocytic leukaemia/normal | |||

| multiple myeloma/normal | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | GDS289 | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/control | |

| Colorectal cancer | GDS2609 | early onset colorectal cancer/healthy control | |

| Cushing’s syndrome | GDS2374 | ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome/control | |

| GIP-dependent Cushing’s syndrome/control | |||

| GIP-dependent nodule/control | |||

| GIP-dependent adenoma/control | |||

| Dermatomyositis | GDS2153 | dermatomyositis/normal | |

| Emphysema | GDS737 | severe emphysema/no or mild emphysema | |

| Endometriosis | GDS2737 | endometriosis/normal | |

| Essential thrombocythaemia | GDS1376 | thrombocythaemia/normal | |

| GDS552 | ET/normal | ||

| GDS761 | malignant/normal | ||

| Familial combined hyperlipidaemia | GDS946 | familial combined hyperlipidaemia/normal | |

| Heart failure | GDS1362 | ischaemic cardiomyopathy/non-failing heart | |

| non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy/non- failing heart | |||

| GDS2154 | inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy/healthy | ||

| GDS2205 | dilated cardiomyopathy/non-failing | ||

| GDS651 | idiopathic dilated/normal | ||

| ischaemic/normal | |||

| Hereditary gingival fibromatosis | GDS1685 | hereditary gingival fibromatosis/normal | |

| HIV infection | GDS2649 | non-progressive HIV infection/uninfected | |

| early HIV infection/uninfected | |||

| chronic HIV infection/uninfected | |||

| Huntington’s disease | GDS1331 | presymptomatic/normal | |

| symptomatic/normal | |||

| Idiopathic myelofibrosis | GDS2397 | idiopathic myelofibrosis/normal | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | GDS1615 | ulcerative colitis/normal | |

| Crohn's disease/normal | |||

| GDS559 | Crohn’s disease/control | ||

| ulcerative colitis/control | |||

| Kidney sarcoma | GDS1282 | clear cell sarcoma of the kidney/control | |

| Wilms’ tumour/control | |||

| GDS505 | RCC/normal | ||

| Leiomyoma | GDS484 | leiomyoma/normal | |

| Lethal congenital contracture syndrome | GDS1295 | LCCS/control | |

| Lung disease | GDS2142 | severe cystic fibrosis/normal | |

| mild cystic fibrosis/normal | |||

| Malignant pleural mesothelioma | GDS1220 | malignant pleural mesothelioma/normal | |

| Melanoma | GDS1375 | malignant melanoma/benign nevi | |

| GDS1989 | lymph node metastasis/normal | ||

| vertical growth phase melanoma/ normal | |||

| melanoma in situ/normal | |||

| atypical nevus/normal | |||

| metastatic growth phase melanoma/normal | |||

| Muscle diseases | GDS1956 | juvenile dermatomyositis/normal | |

| Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy/normal | |||

| calpain 3 mutation/normal | |||

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy/normal | |||

| FKRP mutation/normal | |||

| amyotophic lateral sclerosis/normal | |||

| Becker muscular dystrophy/normal | |||

| acute quadriplegic myopathy/normal | |||

| fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy/normal | |||

| dysferlin mutation/normal | |||

| spastic paraplegia/normal | |||

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | GDS1392 | myelodysplastic syndrome/normal | |

| rheumatoid arthritis, off treatment/normal | |||

| folate deficiency/normal | |||

| vitamin B12 deficiency/normal | |||

| rheumatoid arthritis, on methotrexate/normal | |||

| GDS2118 | refractory anaemia with excess blasts/normal | ||

| refractory anaemia/normal | |||

| refractory anaemia with ringed sideroblasts/normal | |||

| Non-melanoma skin cancer | GDS2200 | squamous cell carcinoma/normal | |

| actinic keratosis/normal | |||

| Obesity | GDS268 | morbidly obese/non-obese | |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | GDS1665 | papillary thyroid carcinoma/normal | |

| GDS1732 | papillary thyroid cancer/normal | ||

| Pituitary adenoma | GDS1253 | GH-secreting adenoma/normal | |

| PRL-secreting adenoma/normal | |||

| non-functioning adenoma/normal | |||

| ACTH-secreting adenoma/normal | |||

| GDS2432 | pituitary adenoma predisposition/control | ||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | GDS1050 | polycystic ovary syndrome/normal | |

| GDS2084 | polycystic ovary syndrome/control | ||

| Prostate cancer | GDS1423 | cancer/normal | |

| GDS1439 | metastatic/benign | ||

| primary/benign | |||

| GDS1746 | metastatic/benign hyperplasia | ||

| basaloid/benign hyperplasia | |||

| Schizophrenia | GDS1917 | schizophrenia/control | |

| Severe combined immunodeficiency | GDS420 | SCID/control | |

| Sickle cell plasma effect on pulmonary artery endothelial cells | GDS1257 | SCD with acute chest syndrome/normal | |

| SCD steady state/normal | |||

| Squamous lung cancer | GDS1312 | cancer/normal | |

| Teratozoospermia | GDS2697 | teratozoospermia/normal | |

| Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia | GDS2418 | vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia/control | |

| MicroRNA permutation or related gene silencing | DGCR8 | GSE13639 | HeLa cells |

| DROSHA | GSE13639 | HeLa cells | |

| GSE6767 | HeLa cells | ||

| IPO8 | GSE14054 | HeLa cells | |

| KSHV microRNA (OE) | GSE16355 | LEC cells | |

| miR-1 (OE) | GSE22002 | HeLa cells | |

| miR-124 (OE) | GSE6207 | HepG2 cell line | |

| miR-125b (KD) | GSE19680 | M07 cells | |

| miR-130b (OE) | GSE17386 | PLC8024 CD133- HCC cells | |

| miR-145 (OE) | GSE18625 | DLD-1 cells | |

| GSE19737 | MDA-MB-231 cells | ||

| miR-146a (KD) | GSE21132 | Jurkat T cells | |

| miR-146a (OE) | GSE21132 | Jurkat T cells | |

| miR-155 (KD) | GSE13296 | dendritic cells | |

| miR-155 (OE) | GSE22002 | HeLa cells | |

| GSE9264 | HEK293 cells | ||

| miR-15a/16-1 (OE) | GSE18866 | CLL-I83E95 cells | |

| miR-16 (KD) | GSE24522 | MMS1 cell line | |

| miR-16 (OE) | GSE24522 | MMS1 cell line | |

| miR-182 (KD) | GSE24824 | human melanoma metastasis | |

| miR-200c (OE) | GSE25332 | Type 2 endometrial cancer cell line, Hec50 | |

| miR-210 (KD) | GSE16962 | HUVEC | |

| miR-210 (OE) | GSE16962 | HUVEC | |

| miR-210/338-3p/ 33a/451 (OE) | GSE15385 | T84 cells | |

| miR-221 (KD) | GSE19777 | MCF7-FR | |

| miR-222 (KD) | GSE19777 | MCF7-FR | |

| miR-26a (OE) | GSE12278 | human BL cell lines:NAM (Ramos) | |

| miR-30d (OE) | GSE27718 | 5B1 melanoma cell line | |

| miR-335 (OE) | GSE9586 | LM2 cell line | |

| miR-338-3p/451 (OE) | GSE15385 | T84 cells | |

| miR-34a (OE) | GSE16674 | K562 cells | |

| GSE7754 | HCT116 cells | ||

| miR-616 (OE) | GSE20543 | LNCaP prostate cells | |

| miR-7 (OE) | GSE14507 | A549 cells | |

| miR-99a (OE) | GSE26332 | C4-2 cells | |

| miR-K12-11 (OE) | GSE9264 | HEK293 cells | |

| top 25 miRNAs (KD) | GSE21577 | HEK 293 cells |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; GIP, gastric inhibitory polypeptide; ET, essential thrombocythaemia; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; LCCS, lethal congenital contracture syndrome; FKRP, fukutin-related protein; GH, growth hormone; PRL, prolactin; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; OE, overexpression; KD, knockdown

Similarity determinations based on the GSEA algorithm

We quantified pair-wise similarities among PRLs as correlation scores based on GSEA. Following the strategy used by Iorio et al,13,20 we extracted the top 250 and the bottom 250 probes as gene signatures. The R package Gene Expression Signature with integrated GSEA was used for the similarity calculations.21 In brief, the enrichment of a signature in a PRL is estimated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for uniform distributions. The signature of permutation A is represented as (upA, downA), with upA representing the top 250 probe sets and downA representing the bottom 250 ones. The final similarity score of PRLs between perturbation A and B (SA,B) is defined as the average enrichment score:

is the enrichment score of signature s (up- and down-regulated parts separated) with respect to the PRL p. Thus, positive similarity scores represent similar regulation tendencies, while negative correlation scores represent opposite regulation tendencies.

Results

Overview of miRNA–disease similarities

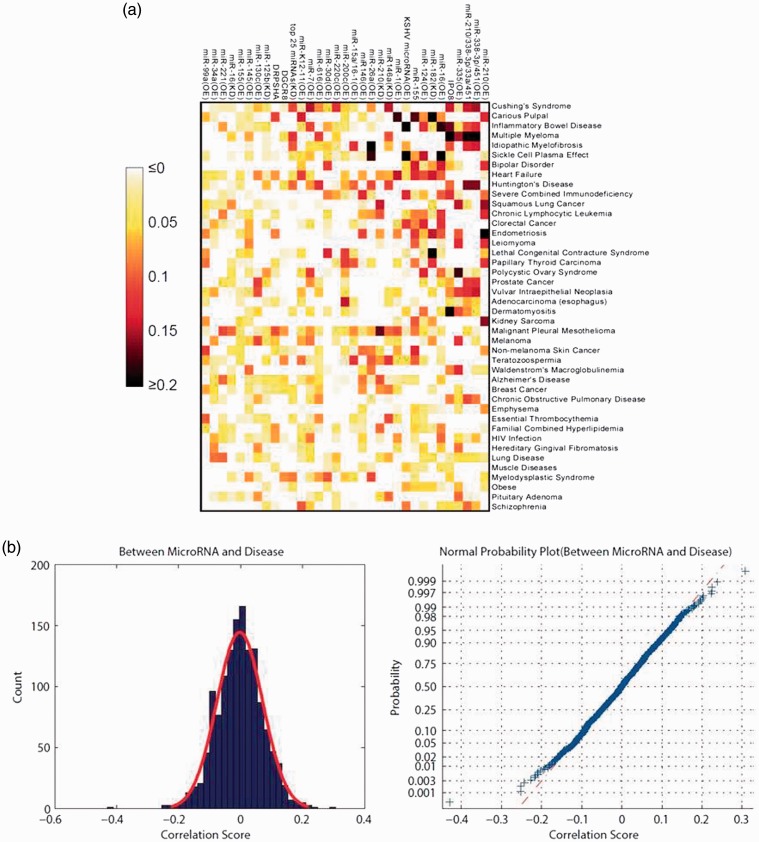

From GSE records, we obtained transcriptional responses including genotype variation of 30 miRNAs for nine knock-down and 21 overexpression treatments. Variations in Drosha, importin 8 (IPO8), and DGCR8 were also included for their functions in miRNA biogenesis. Transcriptional responses representing 42 distinct disease states were collected from GDS records. Based on a GSEA-centred pipeline, we calculated the pair-wise similarities between the transcriptional responses of miRNA variations and disease states (Figure 2(a)). We found that the overall miRNA–disease similarity values followed a normal distribution (mean = −0.002, variance = 0.074, Figure 2(b)). However, we also observed some outliers with extreme similarity scores.

Figure 2.

Pair-wise similarity scores between the transcriptional responses of miRNA variation and disease states. (a) A heat map of similarity scores. miRNA variations and diseases were sorted by their correlations with each other in the top 5%. (b) A distribution and normal probability plot of similarity scores.

Correlated miRNA–disease links

We next focused on highly correlated transcriptional responses to miRNA variation and disease states. The top 5% of miRNA–disease links (n = 69) involving 23 miRNAs and 28 diseases, which are referred to as correlated, are shown in Table 2. The correlations were also illustrated by network to exhibit hubs of miRNA variations and diseases. Among these correlations, we observed both “hub” miRNAs and diseases. Four diseases were linked to four miRNA variations, including Cushing’s syndrome, IBD, multiple myeloma, and carious pulp. The overexpression of miR-210 was correlated with eight disease states, with endometriosis found at the 0.43% percentile. The co-overexpression of miR-338-3 p and miR-451 was also correlated with seven diseases. Interestingly, we found that silencing of IPO8 was correlated with five diseases, and that Drosha or DGCR8, also functional during miRNA biogenesis, were within the top 5% of associations.

Table 2.

miRNA–disease relationships within the top five percentile.

| miRNA perturbation | Disease | CS | PR |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-182 (KD) | Carious pulpal | 0.3078 | 0.07% |

| IPO8 | Multiple myeloma | 0.2376 | 0.14% |

| miR-26a (OE) | Idiopathic myelofibrosis | 0.2247 | 0.22% |

| KSHV microRNA (OE) | Inflammatory bowel disease | 0.2246 | 0.29% |

| miR-182 (KD) | Lethal congenital contracture syndrome | 0.2226 | 0.36% |

| miR-210 (OE) | Endometriosis | 0.2026 | 0.43% |

| miR-16 (OE) | Sickle cell plasma effect | 0.2013 | 0.51% |

| KSHV microRNA (OE) | Sickle cell plasma effect | 0.1972 | 0.58% |

| miR-338-3p/451 (OE) | Multiple myeloma | 0.1953 | 0.65% |

| IPO8 | Dermatomyositis | 0.1918 | 0.72% |

| miR-210/338-3p/33a/451 (OE) | Multiple myeloma | 0.1909 | 0.79% |

| miR-16 (OE) | Inflammatory bowel disease | 0.1817 | 0.87% |

| miR-26a (OE) | Sickle cell plasma effect | 0.1794 | 0.94% |

| miR-1 (OE) | Carious pulpal | 0.1784 | 1.01% |

| miR-335 (OE) | Polycystic ovary syndrome | 0.1751 | 1.08% |

| miR-155 (OE) | Carious pulpal | 0.1747 | 1.15% |

| miR-210 (KD) | Malignant pleural mesothelioma | 0.1662 | 1.23% |

| IPO8 | Inflammatory bowel disease | 0.1655 | 1.30% |

| miR-210/338-3p/33a/451 (OE) | Huntington’s disease | 0.1621 | 1.37% |

| miR-338-3p/451 (OE) | Huntington’s disease | 0.1616 | 1.44% |

| miR-210 (OE) | Kidney sarcoma | 0.1579 | 1.52% |

| miR-210 (OE) | Squamous lung cancer | 0.1548 | 1.59% |

| miR-335 (OE) | Multiple myeloma | 0.1529 | 1.66% |

| miR-338-3p/451 (OE) | Cushing’s syndrome | 0.1503 | 1.73% |

| miR-7 (OE) | Cushing’s syndrome | 0.1487 | 1.80% |

| miR-335 (OE) | Squamous lung cancer | 0.1467 | 1.88% |

| miR-146a (KD) | Cushing’s syndrome | 0.1465 | 1.95% |

| miR-124 (OE) | Sickle cell plasma effect | 0.1465 | 2.02% |

| miR-200c (OE) | Adenocarcinoma (oesophagus) | 0.1463 | 2.09% |

| miR-1 (OE) | Heart failure | 0.1451 | 2.16% |

| miR-182 (KD) | Endometriosis | 0.1448 | 2.24% |

| IPO8 | Cushing’s syndrome | 0.1436 | 2.31% |

| miR-210/338-3p/33a/451 (OE) | Cushing’s syndrome | 0.1423 | 2.38% |

| miR-210 (KD) | Squamous lung cancer | 0.1418 | 2.45% |

| miR-338-3p/451 (OE) | Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia | 0.1416 | 2.53% |

| miR-182 (KD) | Heart failure | 0.1412 | 2.60% |

| miR-155 (OE) | Bipolar disorder | 0.1405 | 2.67% |

| miR-K12-11 (OE) | Carious pulpal | 0.1398 | 2.74% |

| miR-16 (OE) | Bipolar disorder | 0.1385 | 2.81% |

| miR-338-3p/451 (OE) | Idiopathic myelofibrosis | 0.1381 | 2.89% |

| miR-210 (OE) | Carious pulpal | 0.1341 | 2.96% |

| miR-210/338-3p/33a/451 (OE) | Idiopathic myelofibrosis | 0.1334 | 3.03% |

| miR-124 (OE) | Colorectal cancer | 0.1328 | 3.10% |

| miR-155 (OE) | Non-melanoma skin cancer | 0.1323 | 3.17% |

| KSHV microRNA (OE) | Severe combined immunodeficiency disease | 0.1323 | 3.25% |

| miR-124 (OE) | Polycystic ovary syndrome | 0.1322 | 3.32% |

| miR-30d (OE) | Lethal congenital contracture syndrome | 0.1319 | 3.39% |

| miR-210 (OE) | Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia | 0.1319 | 3.46% |

| miR-338-3p/451 (OE) | Inflammatory bowel disease | 0.1304 | 3.54% |

| miR-335 (OE) | Leiomyoma | 0.1297 | 3.61% |

| miR-155 (OE) | Heart failure | 0.1294 | 3.68% |

| miR-146a (OE) | Severe combined immunodeficiency disease | 0.1283 | 3.75% |

| miR-335 (OE) | Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia | 0.1282 | 3.82% |

| miR-210 (OE) | Bipolar disorder | 0.1279 | 3.90% |

| miR-210 (OE) | Leiomyoma | 0.1266 | 3.97% |

| miR-616 (OE) | Huntington’s disease | 0.1259 | 4.04% |

| miR-210/338-3p/33a/451 (OE) | Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia | 0.1259 | 4.11% |

| miR-16(OE) | Colorectal cancer | 0.1236 | 4.18% |

| miR-124 (OE) | Inflammatory bowel disease | 0.1230 | 4.26% |

| miR-222 (KD) | Cushing’s syndrome | 0.1228 | 4.33% |

| miR-338-3p/451 (OE) | Prostate cancer | 0.1224 | 4.40% |

| miR-182 (KD) | Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 0.1224 | 4.47% |

| IPO8 | Severe combined immunodeficiency disease | 0.1221 | 4.55% |

| top 25 miRNAs (KD) | Multiple myeloma | 0.1209 | 4.62% |

| miR-210 (OE) | Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 0.1206 | 4.69% |

| miR-335 (OE) | Melanoma | 0.1202 | 4.76% |

| miR-146a (KD) | Teratozoospermia | 0.1201 | 4.83% |

| miR-15a/16-1 (OE) | Idiopathic myelofibrosis | 0.1196 | 4.91% |

| miR-16 (OE) | Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia | 0.1183 | 4.98% |

KD, knockdown; OE, overexpressionl; CS, Correlation Score; PR, Percentile Rank

We found that the overexpression of miR-210 was most strongly correlated with disease state, showing a wide range of relationships to different diseases. Of the eight diseases linked to miR-210, four were solid cancers, including lung cancer and kidney sarcoma. IBD was identified as a disease connected with the most miRNA genotype variations, and was predicted to share transcriptional phenotype relationships with IPO8, KSHV miRNA, miR-124, miR-16, and miR-338-3 p/451 dysregulation. We also identified multiple myeloma as a disease with five relationships, but connecting with only one miRNA genotype variation containing a single miRNA type: miR-335.

Experimental validation of miRNA differential expression

We selected correlated miRNA links in both disease state samples and controls. Based on bio-sample availability, we selected oesophageal cancer samples to analyse miR-200 c expression (OE), and colorectal cancer samples to assess miR-16 (OE) and miR-124 expression (OE). We also included IBD samples for miR-124 expression as a comparison with previous studies.

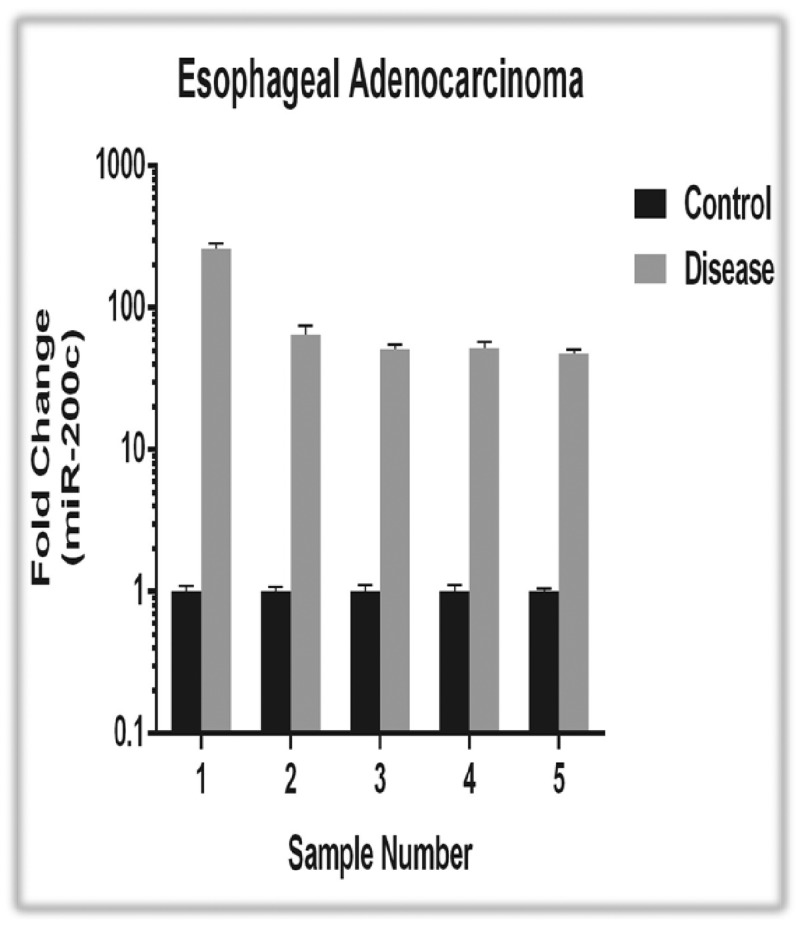

We observed consistently high up-regulation of miR-200 c in the oesophageal cancer samples compared with adjacent control samples (Figure 3). Of four sample pairs, miR-200 c was expressed >47-fold in adenocarcinoma, and in another pair it was expressed 261-fold compared with controls. This result strongly agreed with our prediction that microRNA-200c highly correlated with the development of oesophageal cancer. We also identified six genes that were significantly (P < 0.01) downregulated in association with miR-200 c overexpression and in oesophageal cancer samples using GEO2R of the GEO database. We queried these six genes in TarBase,15 and found that one, ELMO2, has been experimentally validated as a target of miR-200 c.22

Figure 3.

Quantitative RT-PCR assay for miR-200 c expression in paired normal and tumour tissues from five oesophageal adenocarcinoma patients. The expression levels of normal tissues were standardized to 1, and the fold-changes are plotted as means ± SD of three replicates.

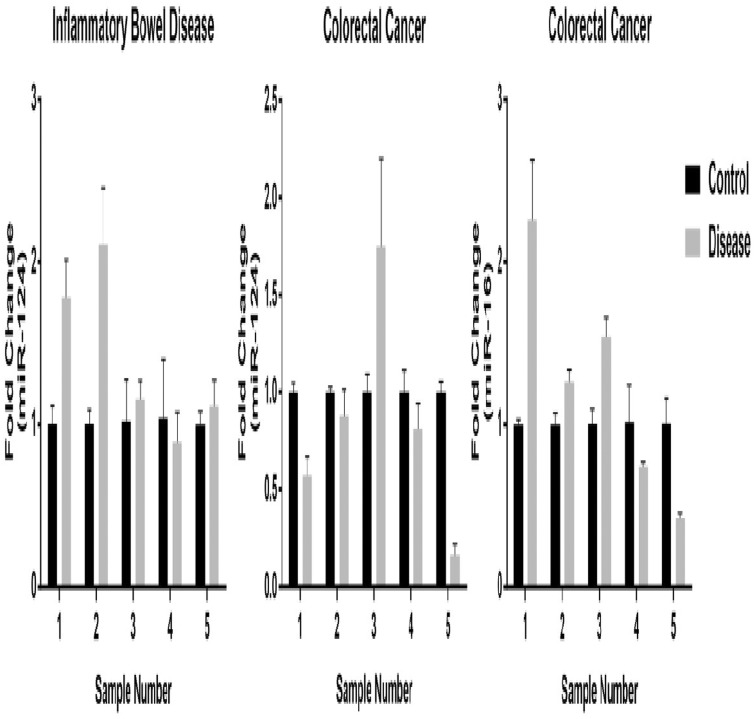

We did not observe consistent upregulated expression of miR-16 or miR-124 in either IBD or colorectal cancer samples compared with controls (Figure 4). In colorectal tissue samples from two CD and three UC patients, miR-124 was shown to be upregulated in two (one CD and one UC). The expression profiles were similar to those of miR-16/24 in colorectal cancer samples.

Figure 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR assays for miR-16 and miR-124 expression in colorectal cancer patients and miR-124 expression in IBD patients. The expression levels of normal tissues are standardized to 1, and the fold-changes are plotted as means ± SD of three replicates.

Discussion

Screening results based on microarray analysis are usually unstable and less functionally related than those derived from other assays. In this study, we connected miRNAs with diseases to better determine their functional relationships. We found that hsa-miR-200 c was upregulated >47-fold in five oesophageal cancer samples compared with normal samples. We also identified the experimentally validated miRNA target ELMO2 as a potential functional link connecting hsa-miR-200 c and oesophageal cancer through a simple overlap analysis of significantly down-regulated genes in hsa-miR-200 c interference and oesophageal cancer samples.

We observed only a slight increase or no change in miR-124 expression in IBD patient samples compared with controls. This is inconsistent with the findings of Koukos et al., who reported miR-124 downregulation in UC samples. This difference could be explained by individual variation in miRNA levels even among patients with the same disease, reflecting differences in development stage or genetic background. Alternatively, it could be caused by the small sample size in our study.

Relationships between IBD, miR-16, and miR-124 have previously been reported,23,24 and the dysregulation of miR-16 has been observed in both CD and UC.23,25 The decreased expression of miR-124 has also been suggested to play a role in promoting inflammation and the pathogenesis of UC through up-regulating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.23 Moreover, miR-335 has previously been shown to play a role in multiple myeloma,26 while miR-210 was reported to be induced by hypoxia in breast cancer.27 This agrees with our observation that half of the diseases associated with miR-210 in the present study were solid tumours, which are known to often be hypoxic.28,29

A large systematic collection of gene expression changes resulting from cellular exposure to perturbations such as small molecules and genetic variations would help the understanding of cellular pathways and the development of therapies and biomarkers. The Library of Integrated Network-Based Cellular Signatures project founded by the National Institutes of Health has therefore been established. This work should increase the power of simulated screening following the accumulation of expression change information under various perturbations.

The main limitation of our study is that we only investigated a small number of miRNAs in association with disease. In the future, we plan to include more diseases and miRNAs and to increase the number of patient samples. We also aim to further explore the relationships between miRNA and diseases using in vivo studies.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China [81273488 to XC Bo, 81230089 to XC Bo, 81102419 to F Li, and 31100951 to M Ni] and the National Key Technologies R&D Program for New Drugs of China [2012ZX09301-003 to KL Liu].

References

- 1.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 2004; 431: 350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004; 116: 281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, et al. Sustained expression of microRNA-155 in hematopoietic stem cells causes a myeloproliferative disorder. J Exp Med 2008; 205: 585–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kloosterman WP, Plasterk RH. The diverse functions of microRNAs in animal development and disease. Dev Cell 2006; 11: 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 2008; 456: 980–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes J, Peruzzi PP, Lawler S. MicroRNAs in cancer: biomarkers, functions and therapy. Trends Mol Med 2014; 20: 460–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA-cancer connection: the beginning of a new tale. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 7390–7394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C. MicroRNomics: a newly emerging approach for disease biology. Physiol Genomics 2008; 33: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson PT, Wang WX, Rajeev BW. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Pathol 2008; 18: 130–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang Q, Wang Y, Hao Y, et al. miR2Disease: a manually curated database for microRNA deregulation in human disease. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37: D98–D104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102: 15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamb J. The Connectivity Map: a new tool for biomedical research. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7: 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iorio F, Bosotti R, Scacheri E, et al. Discovery of drug mode of action and drug repositioning from transcriptional responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 14621–14626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudley JT, Sirota M, Shenoy M, et al. Computational repositioning of the anticonvulsant topiramate for inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 96ra76–96ra76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Vasu VT, Mishra R, et al. Bioinformatics-driven discovery of rational combination for overcoming EGFR-mutant lung cancer resistance to EGFR therapy. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 2393–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang W, Chen X, Liao M, et al. Identification of links between small molecules and miRNAs in human cancers based on transcriptional responses. Sci Rep 2012; 2: 282–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ni M, Ye F, Zhu J, et al. ExpTreeDB: web-based query and visualization of manually annotated gene expression profiling experiments of human and mouse from GEO. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 3379–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sirota M, Dudley JT, Kim J, et al. Discovery and preclinical validation of drug indications using compendia of public gene expression data. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 96ra77–96ra77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu G, Agarwal P. Human disease-drug network based on genomic expression profiles. PLoS One 2009; 4: e6536–e6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iorio F, Tagliaferri R, di Bernardo D. Identifying network of drug mode of action by gene expression profiling. J Comput Biol 2009; 16: 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li F, Cao Y, Han L, et al. GeneExpressionSignature: an R package for discovering functional connections using gene expression signatures. OMICS 2013; 17: 116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu H, Alqadah A and Chang C. The role of microRNAs in regulating neuronal connectivity. Front Cell Neurosci 2014; 7: 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Koukos G, Polytarchou C, Kaplan JL, et al. MicroRNA-124 regulates STAT3 expression and is down-regulated in colon tissues of pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 842–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kalla R, Ventham NT and Kennedy NA. MicroRNAs: new players in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2015, 64(6): 1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Paraskevi A, Theodoropoulos G, Papaconstantinou I, et al. Circulating MicroRNA in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6: 900–904. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Ronchetti D, Lionetti M, Mosca L, et al. An integrative genomic approach reveals coordinated expression of intronic miR-335, miR-342, and miR-561 with deregulated host genes in multiple myeloma. BMC Med Genomics 2008; 1: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Camps C, Buffa FM, Colella S, et al. hsamiR- 210 Is induced by hypoxia and is an independent prognostic factor in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 1340–1348. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Merlo A, Bernardo-Castineira C, Saenz-de-Santa M, et al. Role of VHL, HIF1A and SDH on the expression of miR-210: Implications for tumoral pseudo-hypoxicfate. Oncotarget 2017; 8(4): 6700–6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Jung KO, Youn H, Lee CH, et al. Visualization of exosome-mediated miR-210 transfer from hypoxic tumor cells. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 9899–9910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]