Abstract

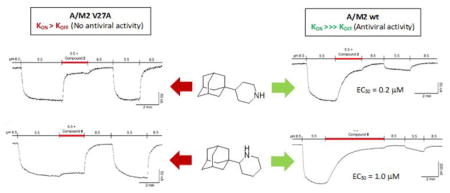

New insights on the amantadine resistance mechanism of the V27A mutant were obtained through the study of novel, easily accessible 4-(1- and 2-adamantyl)piperidines, identified as dual binders of the wild-type and V27A mutant M2 channels of influenza A virus. Their antiviral activity and channel blocking ability were determined using cell-based assays and two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) technique on M2 channels, respectively. In addition, electrophysiology experiments revealed two interesting findings: i) these inhibitors display a different behaviour against the wild-type versus V27A mutant A/M2 channels and, ii) the compounds display antiviral activity when have kd equal or smaller than 10−6 while do not exhibit antiviral activity when kd is 10−5 or higher although may show blocking activity in the TEV assay. Thus caution must be taken when predicting antiviral activity based on percent channel blockage in electrophysiological assays. These findings provide experimental evidence of the resistance mechanism of the V27A mutation to wild-type inhibitors, previously predicted in silico, offer an explanation for the lack of antiviral activity of compounds active in the TEV assay, and may help design new and more effective drugs.

Keywords: Amantadine, drug design, influenza A virus, M2 proton channel, electrophysiology

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The target of amantadine (Amt) and rimantadine, two well-known clinically approved anti-influenza drugs,1 is the M2 protein of influenza A virus (A/M2), a 97-residue integral membrane protein that forms an homotetrameric proton selective transmembrane channel with a critical role in the virus replication cycle.2–11 Unfortunately, most of the circulating strains are Amt-resistant,12 which has compelled the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to deter its use.13 Amt-resistant influenza strains possess one or more mutations in the M2 channel protein.14,15 Although several mutations appear to be viable in vitro,16 a recent analysis of 31,251 M2 protein sequences revealed that the most frequent Amt-resistant mutations in the circulating strains occur at position 31 (S31N) (~ 95%), followed by position 27 (V27A), while other mutations (L26F, A30T, G34E and L38F) were rare.12 Although in this analysis the second most prevalent mutant, V27A, was only observed in about 1% of the sequences, other reports have pointed out that the V27A mutant occurred in 10–77% of influenza virus isolates, depending on the viral strain and season.17,18 Several findings add functional relevance to the V27A mutation: (i) among the most prevalent mutations, V27A is the only one proven to originate from drug selection pressure;19 (ii) while the S31N and L26F mutants are sensitive, to some extent, to Amt, this drug is completely ineffective against the V27A mutant M2 channel;16 (iii) recent studies have noticed an increased frequency of the Amt-resistant V27A/S31N double mutant;20 and, (iv) finally, a virus harboring this V27A/S31N double mutant form of M2 displayed significantly higher mortality compared to wild-type (wt) virus in a mouse model.21

The design of new M2 inhibitors that address the problem of drug resistance is currently of utmost importance. Accordingly, efforts have been recently made to design small molecule inhibitors that target the drug-resistant forms of the influenza A/M2 proton channel.22,23 While numerous compounds targeting the wt channel have been synthesized,24–30 few dual inhibitors of the wt and either the V27A,31–36 or the S31N mutants,37–44 were only recently identified.

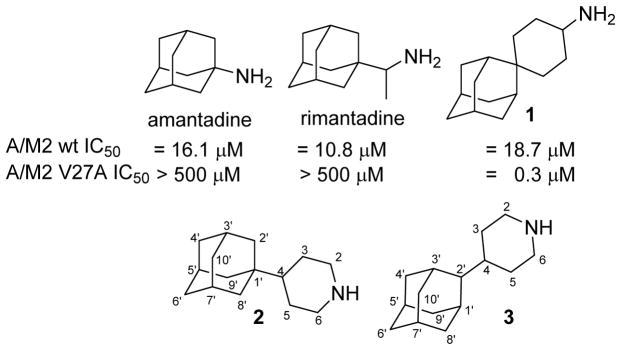

In 2011, Wang et al. used a computationally-driven design for the synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of the spiroadamante 1, a triple inhibitor of the wt, V27A and L26F mutant channels, that features a primary amine.32,36 Taking into account that the synthesis of 1 involves six steps from 2-adamantanone and that potent inhibition of the wt and V27A mutant channels was also achieved with secondary amines,33–35 we wondered whether the synthetically more accessible analogs of 1, such as the piperidine derivatives 2 and 3 described herein, would have similar channel blockage and antiviral activity as compound 1. Of note, it is known that Amt (1-aminoadamantane) is, in some influenza A strains, more potent than its 2-isomer (2-aminoadamantane).45–46 Specifically, the comparison of 2 and 3 would shed light on which position of the adamantane scaffold is more suitable for designing potent V27A inhibitors (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

Structures of Amt, rimantadine, spiroadamantane 1 and novel analogs 2–3.

Results and discussion

Herein we describe the synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of the aforementioned piperidine derivatives 2 and 3 and some related amines and guanidines. The activity of the compounds has been tested against the wt M2 channel as well as the V27A and S31N mutant forms in the two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) assay. Several novel compounds were low micromolar blockers of the wt A/M2 channel and/or the V27A A/M2 variant. Surprisingly, while their blocking abilities in the wt M2 channel nicely correlated with their antiviral activity in a wt-containing influenza A virus, there was a lack of correlation between their V27A channel blockage and antiviral activity of a V27A-containing influenza A virus. Only the 1-adamantyl substituted derivative 2 showed minimal antiviral activity against a virus carrying the V27A A/M2 mutant channel, despite its potent channel blockage. Interestingly, electrophysiology experiments revealed that our dual inhibitors display distinct channel affinities, which translate in two opposite binding patterns,47 explaining the puzzling antiviral activities observed. Overall, these findings add valuable insights into the drug-resistance mechanism postulated for the V27A mutation.48–49

Chemistry

First, we undertook the synthesis of the 4-(1-adamantyl)piperidine, 2, and its related compounds. Togo and coworkers had previously reported the synthesis of a mixture of the (1-adamantyl)pyridines 5 and 6 by radical decarboxylation of 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid, 4, in the presence of pyridine.50 In our hands, compounds 5 and 6 were obtained in a ratio 3 : 1 in 36% overall yield. Both isomers were easily separated by column chromatography. Catalytic hydrogenation of 5 and 6 gave the corresponding piperidines 2 and 8 in 97 and 99% yield, respectively. Kolocouris and coworkers previously reported the synthesis of 8 through a different route, and reported its activity against an H2N2 strain with a wt A/M2 channel.51 For this reason, we also evaluated compound 8 for M2 channel inhibition (see below), although its basic nitrogen atom must adopt a different orientation in the channel compared to known inhibitors.52

While the reaction of amine 2 with 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamide furnished guanidine 7 in 76% yield, several attempts directed towards the synthesis of the corresponding guanidine derived from 8 were unsuccessful, probably reflecting the greater steric congestion around this nitrogen atom (Scheme 1).53

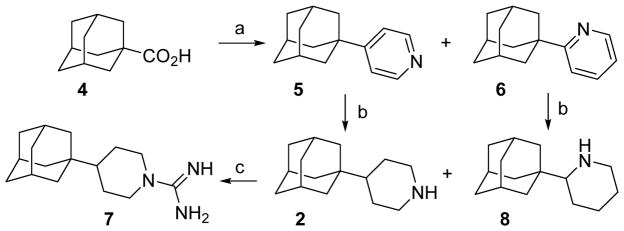

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of (1-adamantyl)piperidines 2 and 8 and guanidine 7.a

aReagents and conditions: a: pyridine, [bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo]benzene, anh. benzene, reflux, overnight, 5, 9%; 6, 27%; b: H2, PtO2, MeOH, 30 atm, 97% yield for 2; 99% yield for 8; c: 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamide hydrochloride, anh. Et3N, acetonitrile, reflux, 6 h, 76% yield.

In order to synthesize piperidines 3 and 12, we followed the pioneering work of Kolocouris et al. for the synthesis of the related 2-(2-adamantyl)piperidine,54 but starting from 4-pyridyl lithium instead of 2-pyridyl lithium. The addition of 4-pyridyl lithium –synthesized in situ from air and light sensitive 4-bromopyridine–, to 2-adamantone, 9, furnished the expected tertiary alcohol 10 in 70% yield. Catalytic hydrogenation of 10 or its hydrochloride under several conditions did not gave the pure alcohol 11, but a complex mixture of 3, 11 and 12 along with other minor impurities, presumably arising from isomerization or rearrangement.54 By crystallization from CH2Cl2, we were able to isolate the pure alcohol 11 from 3 and 12. Several unsuccessful attempts were made to elicit 3 and 12 from the mother liqueurs (containing 3, 12 and remaining 11) by crystallization or column chromatography, but without success. Therefore, we decided to proceed directly to piperidine 3 by treating the mixture with a dehydrating agent, securing the conversion of 11 to 12, followed by catalytic hydrogenation to solely yield the compound 3. Of note, after several fruitless dehydration trials with the acknowledged Burgess’ reagent or anhydrous oxalic acid, which was successfully applied to a very related alcohol,55 we finally were able to dehydrate the tertiary alcohol in very high yields using an extremely inexpensive, facile and fast procedure reported by Álvarez-Manzaneda et al.,56 which involves the use of a mixture of SOCl2 and pyridine in CH2Cl2. The catalytic hydrogenation of the remaining mixture of 3 and 12, furnished the piperidine 3 in nearly quantitative yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 4-(2-adamantyl)piperidines and related compounds from 2-adamantanone, 9.a

aReagents and conditions: a: 4-pyridyl lithium; Et2O/THF, −65 °C to rt, 70% yield; b: 1 atm H2, PtO2, ethanol, rt, 24 h, 93% yield of a mixture of 3, 11 and 12; c: 1) SOCl2, pyridine, anh. CH2Cl2, −60 °C, 30 min, 2) 1 atm H2, Pd/C, methanol, HCl, rt, 2 h, 63% overall yield; d: acetaldehyde, NaCNBH3, AcOH, methanol, rt, 24 h, 76% yield; e: 1) 4-picoline, anh THF, n-BuLi; 2) 9, 2 h, rt, 90% yield; f: 1 atm H2, PtO2, HCl, methanol, 5 days, > 99% yield; g: SOCl2, pyridine, anh. CH2Cl2, −60 °C, 30 min, > 99% yield; h: 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine hydrochloride, anh Et3N, acetonitrile, 70 °C, 6 h, 88% yield for 19, 64% yield for 20; i: 1 atm H2, Pd/C, methanol, HCl, rt, 2 h, 68% yield; j: formaldehyde (37% aqueous solution), NaCNBH3, AcOH, rt, 18 h, 73% yield.

Since water molecules in the M2 channel are believed to play an important role in assisting the binding of the amino group of the putative inhibitor,9,15,57 we decided to check the effect of introducing a tertiary amine in compound 3. This was accomplished through the reductive alkylation of 3, the assumption being that the ethyl derivative 13 should be less potent as M2 channel inhibitor than the secondary amine 3. The reductive alkylation of 3 with acetaldehyde and NaBH3CN in methanol in the presence of acetic acid led to 13.

On the other hand, since the lumen of the V27A M2 protein is wider than that of the wt channel,58–59 size-expanded Amt derivatives may lead to better inhibition of the V27A mutant channel.31–36 Taking into account the poor inhibitory activity displayed by the first series (see discussion of inhibitory activity of 3 and 13 below), a second group of piperidine derivatives was envisaged from 2-adamantanone, 9. The second series featured an increased length thanks to the introduction of an additional carbon atom between the piperidine and the adamantyl group. The addition of the organolithium derivative of 4-picoline to 2-adamantanone furnished alcohol 14 in 90% yield. The subsequent catalytic hydrogenation to the piperidine hydrochloride 15 elapsed in excellent yields. The dehydration of 15 using Alvarez-Manzaneda’s procedure56 led to alkene 16 in quantitative yield. Upon catalytic hydrogenation, 16 smoothly furnished 17 in 79% yield. Finally, guanidines 19 and 20 were synthesized from 16 and 17, respectively, by reaction with 1H-pyrazole-carboxamidine hydrochloride. The tertiary amine 18 was prepared through a reductive alkylation of 17 with formaldehyde in 84% yield (Scheme 2).

Inhibition of the wt A/M2 ion channel and amantadine-resistant mutant forms

The inhibitory activity of the compounds was tested on A/M2 channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes, using the TEVC technique. All inhibitors were initially tested at 100 μM. In the next step, the IC50 values for the compounds that inhibited the V27A channel by more than 60% were obtained using an isochronic (2 min) inhibition assay. The results are given in Table 1. As reference, Amt inhibited the wt A/M2 channel with an IC50 of 16.0 μM, while displaying much lower activity against the S31N mutant channel (IC50 of 200 μM),60 and being totally inactive against the V27A mutant.33

Table 1.

Inhibitory effect of the synthesized compounds on proton channel function of wt or V27A mutant A/M2.a,b

| Compound | A/M2 wt (mean ± SE) | A/M2 V27A (mean ± SE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Inhibition by 100 μM for 2 min (%) | IC50 (μM) | Inhibition by 100 μM for 2 min (%) | IC50 (μM) | |

| Amantadine | 91.0 ± 2.1 | 16.0 ± 1.2 | 8.9 ± 1.0 | >50032 |

| 2 | 92.0 ± 1.4 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 85.7 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 0.6 |

| 3 | 70.7 ± 2.4 | 45.3 ± 2.3 | 61.9 ± 2.3 | 60.6 ± 5.1 |

| 7 | 91.8 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 79.3 ± 2.8 | 16.2 ± 1.7 |

| 8 | 48.1 ± 3.4c | ND | 10.1 ± 0.6 | >500 |

| 11 | 10.9 ± 0.8d | ND | 13.1 ± 0.6 | ND |

| 13 | 43.9 ± 1.0 | ND | 23.5 ± 2.1 | ND |

| 15 | 18.4 ± 2.8 | ND | 14.6 ± 1.9 | ND |

| 16 | 64.0 ± 4.3 | ND | 44.2 ± 1.9 | ND |

| 17 | 76.7 ± 4.0 | ND | 47.3 ± 3.5 | ND |

| 18 | 48.9 ± 10.7 | ND | 29.2 ± 0.9 | ND |

| 19 | 89.9 ± 0.9 | 6.8 ± 1.4 | 63.0 ± 0.9 | 46.0 ± 1.1 |

| 20 | 94.7 ± 1.2 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 77.8 ± 1.5 | 21.7 ± 2.6 |

The activity of the inhibitors was measured using the TEVC technique on A/M2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes; percentage of inhibition was the mean of at least three experiments. For IC50 experiments, 7–9 concentrations were measured, and, at each concentration, experiments were run at least three times.

Isochronic (2 min) values for IC50 are given.

The inhibition for 4 min was ca 75% and > 90% after 6 min of treatment.

The inhibition for 7 min was ca 25% and ca 30% after 10 min. See text and supporting information for details. ND, Not determined.

For the wt M2 channel and any given scaffold, the guanidine derivative was more potent than the corresponding amine for the pairs 19 versus 16, and 20 versus 17, although such a difference was less apparent for the pair of compounds 7 versus 2. Similar trends were also observed from the inhibitory data determined against the V27A mutant. Thus, the presence of the guanidinium fragment presumably offers a better anchoring to the inhibitors in the interior of the wt M2 channel, though this effect is more relevant for compounds with a non-linear structural scaffold, as found in 16 and 17. These results are in line with those previously reported for other sets of molecules.33–34

Moving the adamantane ring from position 2, as found in 8 and in the family of compounds reported by Kolocouris et al.,51,54 to position 4 of the piperidine, as in the rest of our new inhibitors, had a clear incremental effect on the inhibitory activity for both wt and V27A channels. Indeed, the inhibitory effect increases from 48.1 (8) to 92% (2) in the wt M2 channel, and from 10.1 (8) to 85.7% (2) in the V27A mutant M2 channel. On the other hand, the insertion of an extra carbon atom between the adamantane and piperidine rings (3 versus 17) seemed to have little influence on the inhibitory potency. A larger effect, however, was achieved in both channels when moving the anchoring point of the piperidine ring from the C-2 position of adamantane, as in 3, to the C-1 position, as in 2 and 7. This change triggered a substantial increase of the inhibitory activity against both wt and V27A channels, as noted in the 11- and 17-fold reduction of the IC50 observed between compounds 3 and 2. Unluckily, none of the tested molecules had activity against the S31N channel (<10%) (data not shown).

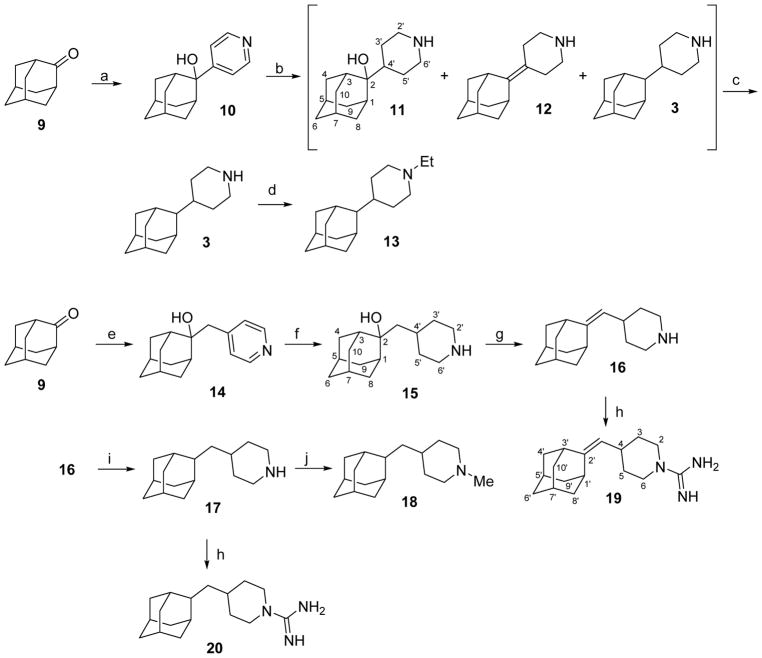

The electrophysiological inhibition assay for wt and mutant channels routinely uses a fixed time of 2 min to calculate the isochronical inhibitory constant (IC50). As the amino alcohols 11 and 15 showed to be very poor inhibitors under these conditions, together with the fact that the bindings were far from saturated at 2 min, additional experiments were performed at longer times, taking 11 as a representative example. Even after 10 min, 11 inhibited only 30% of the wt channel current (data not shown). This observation suggests that the introduction of a hydroxyl group in the middle part of the molecule is deleterious for activity (11 versus 3 or 15 versus 17). Nevertheless, after incubation for 6 min compound 8 led to more than 90% inhibition of the wt channel (Figure 2D). This potent inhibition by compound 8 agrees with its activity in the cell-based antiviral assay (see below), in which the compound is applied for longer incubation times to achieve equilibrium. In contrast, the inhibition of the V27A M2 mutant channel with 8 was already at steady-state after just 1 min (Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of the A/M2 wt channel (derived from the A/Udorn/307/72 H3N2 virus strain) and V27A mutant form, using the TEVC technique in Xenopus oocytes. Oocytes were bathed in Barth solution at pH = 8.5 and pH = 5.5. Current was clamped at −20 mV and the indicated compounds were applied at 100 μM in pH 5.5 solution once the inward current reached maximum amplitude in A/M2 wt channel (A–D) and V27A mutant channel (E–H).

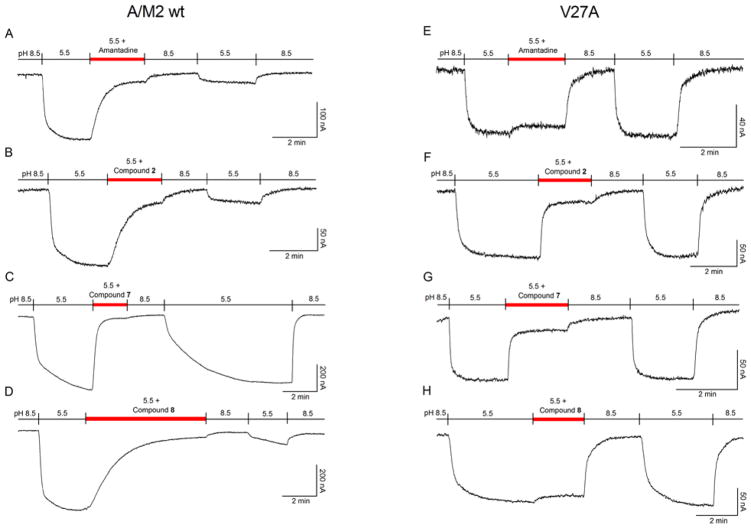

Antiviral activity and cytotoxicity in cell culture

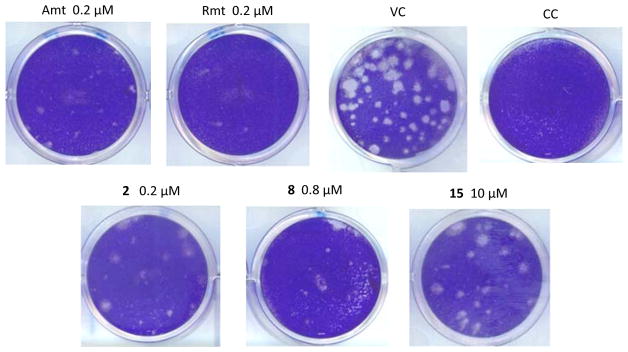

The anti-influenza virus activity of the compounds was determined in MDCK cells using two different assays, i.e. a 24-h virus yield assay (based on RT-qPCR quantification of virus in the supernatant), and a 72-h virus plaque reduction assay (PRA), both with the A/HK/7/87 virus (H3N2 subtype), which carries a wt M2 protein (Table 2). Guanidine derivatives 7, 19 and 20 did not display antiviral activity (data not shown). In the PRA (Figure 1), amines 2 and 8 and amino alcohol 15 were found to be active, with 2 being equally potent as Amt (EC50 = 0.14 μM for the two compounds in the PRA assay). Considering that compound 11, an aminoalcohol like 15, did not block the wt M2 channel in the TEVC assay even at long times, the antiviral activity of 15 in cell culture suggests the involvement of another mechanism of action, an observation that we previously made for other adamantane derivatives.46,61–62 In the case of compound 8, its greater potency in the PRA compared to the electrophysiological method relates to its slow A/M2 binding kinetics (see Figure 2 and Table 3). Of note, the antiviral activity determined for 8 (EC50 = 1.0 μM) is very similar to the EC50 value of 3.3 μM that was reported for this compound by Kolocouris et al. in an assay with an H2N2 virus strain.51 In addition, the antiviral activity of 2 and 8 (but not compound 15) was confirmed in our virus yield assay (Table 2). This antiviral effect was seen at concentrations well below the cytotoxic concentrations, since compound 2 had a selectivity index (ratio of CC50 to EC50 based on 72-h compound exposure time) of 128, and compound 8 was devoid of cytotoxicity at 100 μM, the highest concentration tested.

Table 2.

Antiviral activity in influenza virus-infected MDCK cells.a

| Compound | Antiviral activity (μM) against A/HK/7/87 (wt M2) | Cytotoxicity (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (PRA)b | EC99 (Virus yield)c | CC50d | |

| 2 | 0.14 | ≥1.7 | 18 |

| 3 | ND | ≥50 | >100 |

| 7 | >50 | >2 | 10 |

| 8 | 1.0 | 3.5 | >100 |

| 11 | >100 | 76 | >100 |

| 13 | >10 | >10 | 25 |

| 15 | 10 | >50 | >50 |

| 16 | >5 | >10 | 25 |

| 17 | >10 | >2 | 15 |

| 18 | >10 | >2 | 6.2 |

| 19 | >5 | >2 | 19 |

| 20 | >10 | >2 | 3.8 |

|

| |||

| Amantadine | 0.14 | 0.51 | >500 |

| Rimantadine | 0.016 | 1.1 | >500 |

MDCK: Madin-Darby canine kidney cells; virus strain: A/HK/7/87 (A/H3N2 carrying wt M2). None of the compounds displayed activity against the A/PR/8/34 strain bearing the S31N mutant M2 channel (data not shown).

EC50 in the virus plaque reduction assay (PRA): concentration at which the plaque number is reduced by 50% compared to untreated virus control.

EC99: compound concentration giving 2-log10 reduction in virus yield, as determined by quantifying the virus in the supernatant at 24 h post infection, using an RT-qPCR based method.63

CC50: 50% cytotoxic concentration, as determined by the MTS cell viability test in uninfected cells exposed to the compounds during 72 h. Values shown are the mean of 2–3 determinations. ND, not determined.

Figure 1.

Activity of the compounds in the influenza virus plaque reduction assay. MDCK cells were infected with influenza virus (strain A/HK/7/87; 30 PFU per well) in the presence of the test compounds. After 72 h incubation, plaques were visualized by crystal violet staining. VC: mock-treated virus control; CC: uninfected cell control.

Table 3.

Rate constants for association (kon) and dissociation (koff) of the compounds to/from the A/M2 wt or V27A mutant channels.a

| Compound | A/M2 wt (mean ± SE) | V27A (mean ± SE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| kon (M−1 s−1) | koff (s−1) | kon (M−1 s−1) | koff (s−1) | |

| Amantadine | 293 ± 37 (4) | 3×10−4 (ref 44) | 360 ± 18 (4) | 16×10−2 (1) |

| 2 | 259 ± 29 (4) | ND | 1369 ± 149 (9) | 6×10−2 ± 0.006 (5) |

| 7 | 654 ± 51 (5) | 10−2 ± 0.001 (3) | 1028 ± 167 (9) | 14×10−2 ± 0.041 (3) |

| 8 | 119 ± 11 (3) | ND | 595 ± 48 (4) | 4×10−2 (1) |

Currents from Figure 2 were fitted to a single exponential function (y=e−t/τ + constant with r>0.94) and the time constant τ was used to calculate the forward rate constant after addition of compound (kon = 1/[compound] τ) and the reverse rate constant during the washout at pH 5.5 (koff = 1/τ).47 Number of tested oocytes in brackets. ND, not determined.

The anti-influenza virus activity of compounds 2, 3, 7 and 19, that inhibited the V27A channel (Table 1), was also determined in MDCK cells using a 46-h virus PRA with the A/WSN/33 virus (H1N1 subtype), which carries a N31S/V27A M2 protein. Compound 8, that did not inhibit the V27A channel (Table 1 and Figure 2H) but showed antiviral activity against the A/HK/7/87, was also assayed. Surprisingly, in addition to 8, compounds 3, 7 and 19 were inactive and only a weak activity was found for compound 2 that clearly did not match its high potency in the TEVC assay (Table 1 and Figure S1).

Inhibition kinetics of the wt A/M2 ion channel and amantadine-resistant mutant forms

To further characterize the inhibitory effects on wt and V27A channels and rationalize the antiviral results, the current kinetics of the most potent channel blockers 2, 7, 8, 19 and 20 were determined and compared with the profile obtained for Amt (Figure 2 and Table 3; see also results for 19 and 20 in SI). Analysis of the curves for the wt channel (left panels in Figure 2) showed that the forward rate constant (kon) for association and inhibition by compound 7 (654 ± 51 M−1 s−1) was around 2.3-fold faster than the values obtained for compound 2 (259 ± 29 M−1 s−1) and Amt (293 ± 37 M−1 s−1). At saturating compound concentrations (100 μM), the slow koff rate found for compounds 2 and 8 identified them as strong binders, since that resembles the behavior of Amt, which has a koff rate of 3×10−4 s−1 (Figure 2A–B).47 Assuming that the inhibition by compounds 2 and 8 might be partially reversible,47 we performed several experiments at low inhibitor concentrations for obtaining the Koff rate, but we found that, within the time frame of the experiments (ca. 50–60 min), the inhibition by both compounds was essentially irreversible (see Figure S4).36 Contrarily, compound 7 dissociated from the channel after 5 min, an observation that may explain the failure to display antiviral activity in the PRA despite being able to block the channel (Figure 2C). This result is consistent with the 33-fold slower koff found for Amt (3×10−4 s−1)47 relative to compound 7 (10−2 s−1) (Table 3). Compounds 19 and 20, with rapid kon and koff values, displayed the same weak binding affinity as 7 (see Figures S2 and S3).

In the case of the V27A mutant channel (right panels in Figure 2), compounds 2 and 7 had higher affinity (IC50 of 3.6 ± 0.6 and 16.2 ± 1.7 μM, respectively) compared with Amt (IC50 > 500 μM)33 and compound 8 (IC50 > 500 μM) (Table 1). Despite 2 and 7 showed greater kon rate constants compared to Amt and 8, which allowed them to display channel blockade at the 2 min assay (unlike Amt or 8), all four compounds have similar koff. Hence, although compounds 2 and 7 can bind the V27A channel (Table 1), i. e., they show a fast association that allows to follow the inhibition of the proton current, the weak binding affinity facilitates dissociation during washing with drug-free pH 8.5 buffer, rendering the channel functional again (Figure 2E–H and Table 3).36,47 This behavior agrees with the resistance mechanism proposed for Amt in the V27A mutant.49 Interestingly, the case of compound 2 clearly exemplifies the different outcomes in the wt and V27A channels: although this compound has similar IC50 values (4.1 and 3.6 μM, respectively, Table 1), the faster koff in the mutated channel, probably reflecting a worse fitting to the wider pore,58–59 allows the compound to be washed away, revoking the channel blockade. This fact correlates with the antiviral activity assays (see above), justifying that some compounds with promising V27A mutant M2 channel blockade activities fail to behave as good antivirals likely due to fast dissociation (fast koff rate).

Conclusions

Several adamantane derivatives have been synthesized and tested as potential inhibitors of the influenza A virus. The novel 4-(1-adamantyl)piperidine 2 and its guanidine derivative 7, were low micromolar blockers of the wt and V27A mutant M2 channels. The following SAR trends were observed: (i) alkylation of a secondary amine to a tertiary amine reduced the activity (3 vs 13 and 17 vs 18); (ii) switching the adamantane ring from position 2 to position 4 of the piperidine, triggered faster association rate to the channel (8 vs 2); (iii) moving the piperidine ring from the C-2 position of the adamantane, as in 3, to the C-1 position, as in 2, led to an increase in the inhibitory activity on both channels. The inhibitory activity of 2 was confirmed in cell-based antiviral (virus plaque reduction and virus yield) assays. Of note, the most potent compound in the antiviral assays, amine 2, is synthetically accessible in just two steps from commercially available precursors and has a selectivity index of 128 (Table 2).

Remarkably our electrophysiological experiments have revealed some unexpected differences among structurally very similar compounds. Namely, amine 2 is a strong binder of the wt channel (IC50 = 3.6 μM, Table 1, see also Figure 2B), while its binding being fast and weak in the V27A channel (Figure 2F). Its guanidine derivative, 7, behaves in both channels as a fast and weak binder (Figures 2C and 2G), meanwhile the compound 8, its 2-piperidine isomer, shows a very slow but strong binding with the wt M2 channel (Figure 2D) and no remarkable binding at all with the V27A mutant channel (Figure 2H).

Building up from these findings we can conclude that: (1) M2 channel blockers with potent influenza A antiviral activity usually show steady binding to the channel (kon ≫ koff),47 (2) caution has to be taken when defining M2 inhibitors solely by isochronic inhibition assays at 2 min, M2 channel blockers are very slow binders, so the IC50 depends on the amount of time the drug is exposed to the target. In our case a good correlation between the TEVC and the antiviral activity for the amine 2 (IC50 = 4.1μM and EC50 = 0.14 μM, respectively) was observed in inhibiting wt M2 (because in this case kon ≫ koff). Nevertheless, while all the guanidine derivatives were pointed out to be potent dual inhibitors of the M2 and V27A channels by TEVC assays, their inactivity in the plaque reduction assays proved the TEVC predictions to be completely wrong. On top of that, the TEVC assay failed, under the standard 2 min conditions, to identify 8, shown to be one of the most promising antivirals synthesized in this work (see Tables 1 and 2). (3) The weak affinity observed in our compounds for the V27A A/M2 mutant channel, goes in line with the proposed drug resistance mechanism by in silico11,59,64–65 and structural58 approaches. This is the first time the drug resistance mechanism of the V27A A/M2 mutant channel is experimentally evidenced. Hence, our findings not only reinforce the previous in silico hypothesis but also lead to a more profound understanding of the influenza A virus resistance mechanism and to potential avenues for M2 inhibitor design.

Experimental section

Chemical Synthesis

General Methods

Melting points were determined in open capillary tubes with a MFB 595010M Gallenkamp. 400 MHz 1H/100.6 MHz 13C NMR spectra, and 500 MHz 1H NMR spectra were recorded on Varian Gemini 300, Varian Mercury 400, and Varian Inova 500 spectrometers, respectively. The chemical shifts are reported in ppm (δ scale) relative to internal tetramethylsilane, and coupling constants are reported in Hertz (Hz). Assignments given for the NMR spectra of the new compounds have been carried out on the basis of DEPT, COSY 1H/1H (standard procedures), and COSY 1H/13C (gHSQC and gHMBC sequences) experiments. IR spectra were run on Perkin-Elmer Spectrum RX I spectrophotometer. Absorption values are expressed as wave-numbers (cm−1); only significant absorption bands are given. The GC/MS analysis was carried out in an inert Agilent Technologies 5975 gas chromatograph equipped with an Agilent 122–5532 DB-5MS 1b (30 m × 0.25 mm) capillary column with a stationary phase of phenylmethylsilicon (5% diphenyl – 95% dimethylpolysiloxane), using the following conditions: initial temperature of 50 °C (1 min), with a gradient of 10 °C / min up to 300 °C, and a temperature in the source of 250 °C. Solvent Delay (SD) of 4 minutes and a pressure of 7,35 psi. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 AC.C (35–70 mesh, SDS, ref 2000027). Thin-layer chromatography was performed with aluminum-backed sheets with silica gel 60 F254 (Merck, ref 1.05554), and spots were visualized with UV light and 1% aqueous solution of KMnO4. The analytical samples of all of the new compounds which were subjected to pharmacological evaluation possessed purity ≥95% as evidenced by their elemental analyses.66

Synthesis of 4-(1-adamantyl)piperidine hydrochloride, 2·HCl

A solution of compound 6 (830 mg, 3.9 mol) and PtO2 at 10% (83 mg) in methanol (100 mL) containing few drops of HCl was hydrogenated at room temperature, at a pressure of 30 atm until no more hydrogen absorption was observed. The resulting suspension was filtered and the residue washed with methanol. The solvent was removed under vacuo to obtain amine 2·HCl (970 mg, 97% yield) as a white solid. The analytical sample was obtained by crystallization from 2-propanol, mp 272–273 °C (dec). IR (KBr) 3674, 2900, 2846, 2728, 2671, 2503, 1597, 1446, 1396, 1344, 1075, 1023, 960 cm−1. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.20 (tt, J = 12.3 Hz, J′ = 3.2 Hz, 1 H, 4-H), 1.49 [qd, J = 14.0 Hz, J′ = 4.0 Hz, 2 H, 3(5)-Hax], 1.57 [d, J = 2.6 Hz, 6 H, 2′ (8′, 9′)], 1.68 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 3 H) and 1.77 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 3 H) [4′ (6′, 10′)-Hexo and Hendo], 1.94 [bs, 2 H, 3(5)-Heq], 1.99 [bs, 3 H, 3′ (5′, 7′)-H], 2.91 [dt, J = 13.1 Hz, J′ = 2.9 Hz, 2 H, 2(6)-Hax], 3.42 [dt, J = 12.4 Hz, J′ = 2.2 Hz, 2 H, 2(6)-Heq]. 13C-NMR (125.7 MHz, CD3OD) δ 23.6 [CH2, C3(5)], 30.1 [CH, C3′ (5′, 7′)], 35.0 (C, 1′), 38.3 [CH2, C4′ (6′, 10′)], 40.3 [CH2, C2′ (8′, 9′)], 45.8 (CH, C4), 46.0 [CH2, C2(6)]. MS (EI), m/e (%); main ions: 219 (M·+, 100), 218 (21), 205 (60), 163 (15), 135 (C10H15+, 83), 93 (27), 91 (19), 85 (83), 84 (50), 83 (21), 79 (33), 77 (16), 58 (18), 57 (48), 56 (25), 55 (21).

4-(Adamantan-2-yl)piperidine hydrochloride, 3·HCl

SOCl2 (0.42 mL, 5.8 mmol) was slowly added to a mixture of 3, 11 and 12 (850 mg; ca 3.9 mmol) and pyridine (0.84 mL) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (8 mL) at −60 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at this temperature under argon atmosphere for 30 min and quenched with sat. aq. Solution of NaHCO3 (1 mL) and the cooling bath was removed. The mixture was poured into diethyl ether-water (90 mL : 20 mL) and the phases were shaken and separated. The organic phases were reunited, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure. The yellow solid residue (a mixture of 3 and 12, GC/MS) was solved in methanol containing few drops of conc. HCl and hydrogenated with Pd/C (460 mg) at room temperature and 1 atm pressure of H2, for 2 hours. After filtration of the catalyst, the solvent was concentrated under reduced pressure and the white solid obtained was washed with pentane, giving 183 mg (21% yield) of the piperidine 3·HCl. An analytical sample was obtained by crystallization from dichloromethane, mp 252–254 °C. IR (ATR) 3311, 2931, 2911, 2850, 2820, 2785, 2724, 2501, 1598, 1451, 1423, 1302, 1279, 1041, 983 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.21–2.02 (complex signal, 20 H, adamantyl-H, 4-H and 3(5)-H2], 2.91 [td, J = 12.4 Hz, J′ = 3.2 Hz, 2 H, 2(6)-Hax], 3.34 [broad d, 2 H, J = 12.4 Hz, 2(6)-Heq]. 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 28.6 [CH2, C3(5)], 29.1 (CH) and 29.5 (CH) (C5′ and C7′), 29.7 [CH, C1′ (3′)], 32.7 [CH2, C4′ (9′) or C8′ (10′)], 34.6 (CH, C4), 39.3 (CH2, C6′), 40.2 [CH2, C8′ (10′) or C4′ (9′)], 45.8 [CH2, C2(6)], 50.4 (CH, C2′). GC/MS (EI), m/e (%); main ions: 219 (M·+, 17), 204 (100), 174 (20), 162 (93), 84 (32), 82 (18), 79 (20), 57 (22), 56 (27). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C15H25N+H+]: 220.2060, found: 220.2059.

4-(1-adamantyl)pyridine, 5 and 2-(1-adamantyl)pyridine, 6

A solution of 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid, 4, (11.35 g, 63.0 mmol), pyridine (5.1 mL, 63.0 mmol), bis[(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo]benzene (9.34 g, 21.8 mmol) in anhydrous benzene (100 mL) was heated under reflux overnight. The reaction was cooled down and the organic phase was washed with a 10 N aqueous solution of NaOH (2 × 100 mL) and the aqueous layer was washed with AcOEt (2 × 100 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with a 1 N solution of HCl (3 × 100 mL) and the aqueous was neutralized to pH = 14 with a 10 N solution of NaOH. Then, the aqueous layer was extracted with AcOEt (3 × 100 mL) and the organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under vacuo to obtain a mixture of pyridines 5 and 6. This mixture was purified by column chromatography (SiO2). Compound 5 was obtained (CH2Cl2:MeOH 98.5:1.5, 830 mg, 9.3% yield) as a beige solid. Compound 6 was obtained (CH2Cl2:MeOH 99.5:0.5, 830 mg, 27.4% yield) as a white solid. The spectroscopical data of both compounds matched the previously reported.50

Synthesis of N-amidyl-4-(1-adamantyl)piperidine hydrochloride, 7·HCl

In a 10 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a condenser and a magnetic stirrer, a suspension of amine 2·HCl (484 mg, 1.9 mmol), 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine hydrochloride (333 mg, 2.3 mmol), anhydrous triethylamine (0.47 mL) in acetonitrile (5 mL) was prepared. The reaction was heated at 70 °C for 6 hours. The reaction was cooled down and stored at 4°C overnight. The suspension was filtered out and the filtrate washed with cold acetonitrile obtaining the guanidine 7·HCl as a beige solid (428 mg, 76% yield). The analytical sample was obtained by crystallization from 2-propanol, mp > 300 (dec.). IR (KBr) 3112, 2898, 2845, 1639, 1597, 1526, 1446, 1345, 1195, 1160, 967, 743 cm−1. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.18 (tt, J = 12.4 Hz, J′ = 3.2 Hz, 1 H, 4-H), 1.31 [qd, J = 13.2 Hz, J′ = 3.6 Hz, 2 H, 3(5)-Hax], 1.57 [d, J = 2.4 Hz, 6 H, 2′ (8′, 9′)], 1.68 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 3 H) and 1.76 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 3 H) [4′ (6′, 10′)-Hexo and Hendo], 1.83 [dd, J = 13.2 Hz, J′ = 1.6 Hz, 2 H, 3(5)-Heq], 1.98 [bs, 3 H, 3′ (5′, 7′)-H], 2.98 [td, J = 13.2 Hz, J′ = 2.0 Hz, 2 H, 2(6)-Hax], 3.93 [dt, J = 13.2 Hz, J′ = 2.4 Hz, 2 H, 2(6)-Heq]. 13C-NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ 26.1 [CH2, C3(5)], 30.1 [CH, C3′ (5′, 7′)], 35.0 (C, 1′), 38.3 [CH2, C4′ (6′, 10′)], 40.5 [CH2, C2′ (8′, 9′)], 47.5 (CH, C4), 47.6 [CH2, C2(6)], 157.4 (C, C=NH). MS (EI), m/e (%); main ions: 261 (M·+, 2), 219 (13), 135 (C10H15+, 30), 129 (96), 128 (100), 127 (38), 101 (11), 93 (17), 91 (16), 88 (16), 87 (17), 86 (15), 85 (15), 79 (23), 77 (12), 75 (13), 74 (14), 67 (11), 57 (24), 56 (18), 55 (16).

Synthesis of 2-(1-adamantyl)piperidine hydrochloride, 8·HCl

From a solution of compound 6 (2.25 g, 10.5 mol) and PtO2 at 10% (225 mg) in MeOH (100 mL) containing few drops of HCl and following the same procedure than the previously mentioned for the synthesis of 2·HCl, amine 8·HCl (2.67 g, 99% yield) was obtained as a white solid, 262–265 °C (dec). IR (ATR) 3392, 2911, 2855, 2754, 2698, 2481, 1585, 1431, 1413, 1375, 1342, 1304, 1276, 1054, 1016, 971, 814 cm-1. cm−1. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.40–2.04 [complex signal, 18 H, 3-H2, 4-H2, 5-H2, 2′ (8′,9′)-H2, 4′ (6′,10′)-H2], 2.06 [broad s, 3 H, 3′ (5′,7′)-H], 2.71 (dd, J = 11.6, J′ = 2.4 Hz, 1 H, 2-H), 3.00 (dt, J = 13.0 Hz, J′ = 3.2 Hz, 1 H, 6-Hax), 3.41 (dm, J = 13.0 Hz, 1 H, 6-Heq). 13C-NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ 23.6 (CH2), 23.8 (CH2) and 23.9 (CH2) (C3, C4 and C5), 29.6 [CH, C3′ (5′, 7′)], 36.0 (C, 1′), 37.6 [CH2, C4′ (6′, 10′)], 39.1 [CH2, C2′ (8′, 9′)], 47.6 (CH2, C6), 46.0 (CH, C2). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C15H25N+H+]: 220.2060, found: 220.2061.

2-(4-Pyridyl)adamantan-2-ol, 10

To a 2.5 M solution of n-butyllithium in hexane (11.7 ml, 29.25 mmol) was added dropwise with stirring at −75 °C, a solution of the released base, 4-bromopyridine (5.048 g, 31.95 mmol) in anhydrous ether (80 mL) under argon atmosphere, giving a fuchsia light solution that was further stirred at −65 °C for 20 min. Afterwards a solution of 2-adamantanone (4 g, 26.6 mmol) in anhydrous ether (60 mL) and THF (2 mL) was added dropwise. The stirring was continued for 3 hours, after which the pink mixture was then allowed to gradually warm to ambient temperature and left stirring overnight. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (40 mL) and poured into a 5 N HCl solution (40 ml) under ice-cooling. The solution was stirred for 20 minutes and the acidic aqueous phase were separated (2 × 40mL) and basified with NaOH 5N (100 mL) over an ice bath. The resultant solid was filtered while cold under vacuum and washed with cold pentane and dried to give 10 was obtained (4.3 g, 70% yield) as a white solid, 184–186 °C. IR (ATR) 2906, 2860, 1686, 1600, 1539, 1451, 1410, 1345, 1276, 1241, 983, 842 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.56 (broad d, J = 12.8 Hz, 2 H, 6-H2), 1.74–1.93 [complex signal, 8 H, 4(9)-H2 and 8(10)-H2], 2.48 [d, J = 12.4 Hz, 2 H, 5(7)-H], 2.61 [broad s, 2 H, 1(3)-H], 8.20 [d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H, 3′ (5′)-H], 8.82 [d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2′ (6′)-H]. 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ 28.1 (CH) and 28.6 (CH) (C5 and C7), 33.5 (CH2) and 35.5 (CH2) [C4(9) and C8(10)], 35.9 [CH, C1(3)], 38.3 (CH2, C6), 75.8 (C, C2), 125.9 [CH, C3′ (5′)], 143.1 [CH, C2′ (6′)], 168.3 (C, C4′). MS (EI), m/e (%); main ions: 229 (M·+, 29), 212 (14), 211 [(M-H2O)·+, 72], 151 (100), 109 (20), 106 (32), 93 (20), 91 (16), 81 (30), 80 (50), 79 (93), 78 (23), 77 (16), 67 (17).

2-(4-Piperidinyl)adamantan-2-ol, 11

A solution of the aminoalcohol 10 (980 mg, 4.27 mmol) in absolute ethanol, was hydrogenated over PtO2 (100 mg) at room temperature and 1 atm pressure for 24 hours. After filtration in order to remove the catalyst, it was concentrated under reduced pressure and the white solid obtained, washed with pentane, giving 930 mg (aprox. 93%) of a mixture of 11, 3 and 12. An analytical sample of 11 was obtained by crystallization from dichloromethane, mp > 231 °C (dec.); IR (ATR) 3427, 2906, 2850, 2794, 2729, 2663, 2501, 1694, 1590, 1451, 1433, 1410, 1357, 1327, 1287, 1137, 1054, 1034, 991, 950, 928, 756 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.44–1.94 (complex signal, 16 H, adamantyl-H and 3′ (5′)-H2], 2.08 (tt, J = 11.6 Hz, J′ = 3.6 Hz, 1 H, 4′-H), 2.13 [d, J = 12.4 Hz, 2 H, adamantayl-H), 2.4–2.7 (very broad signal, 2 H, NH and OH), 2.67 [td, 2 H, J = 12.4 Hz, J′ = 2.8 Hz, 2′ (6′)-Hax], 3.37 [broad d, 2 H, J = 12.4 Hz, 2′ (6′)-Heq]. 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.2 [CH2, C3′ (5′)], 26.9 (CH) and 27.2 (CH) (C5 and C7), 33.0 [CH2, C4(9) or C8(10)], 33.6 [CH, C1(3)], 33.7 [CH2, C8(10) or C4(9)], 38.1 (CH, C4′), 38.2 (CH2, C6), 46.4 [CH2, C2′ (6′)], 75.0 (C, C2). GC/MS (EI), m/e (%); main ions: 235 (M·+, 9), 234 (42), 219 (18), 218 (100), 216 (28), 151 (24). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C15H25NO+H+]: 236.2009, found: 236.2011.

Synthesis of 4-(adamantan-2-yl)-1-ethylpiperidine hydrochloride, 13·HCl

To a solution of 3·HCl (100 mg, 0.39 mmol) in water (5 mL) was added a 10 N aqueous solution of NaOH. It was then extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5mL) and the organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under vacuo (yellowish oil, 85 mg, quantitative yield). This oil was dissolved in MeOH (5 mL) and sodium cyanoborohydride (73.5 mg, 1.17 mmol), acetaldehyde (21 mg, 0.48 mmol) and glacial acetic acid (0.1 mL) were added to the solution. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 8 hours and a second portion of sodium cyanoborohydride (73.5 mg, 1.17 mmol) and acetaldehyde (21 mg, 0.48 mmol) were added. The yellow solution was further stirred at room temperature overnight. It was concentrated under vacuo and the yellow oil was solved in water (5 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under vacuo. Column chromatography of the solid (silica gel, hexane/EtOAc mixtures) gave the pure amine as an off-white solid (84 mg, 76%). An analytical sample of the hydrochloride was obtained by adding an excess of Et2O·HCl to a solution of 13 in EtOAc followed by filtration of the obtained solid, mp > 300 °C (dec.); IR (ATR) 3336, 2911, 2850, 2643, 2531, 1648, 1453, 1433, 1393, 1244, 1107, 976 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.35 (t, J= 7.4 Hz, 3 H, NCH2CH3), 1.58 [d, J = 12.4 Hz, 2 H, 4′ (9′)-Ha or 8′ (10′)-Ha], 1.74 [d, J = 10.4 Hz, 2 H, 8′ (10′)-Ha or 4′ (9′)-Ha], 1.76–1.95 [complex signal, 13 H, 3(5)-H2 and 9-adamantyl-H], 2.09 (m, 1 H) and 2.12 (m, 1 H) (1′-H and 3′-H), 2.93 [td, J = 12.6 Hz, J′ = 2.4 Hz, 2 H, 2(6)-Hax], 3.15 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2 H, NCH2CH3), 3.58 [dm, J = 12.6 Hz, 2 H, 2(6)-Heq]. 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.6 (CH3, NCH2CH3), 28.9 [(CH2, C3(5)], 29.1 (CH) and 29.4 (CH) (C5′ and C7′), 29.9 [CH, C1′ (3′)], 32.7 [CH2, C4′ (9′) or C8′ (10′)], 34.2 (CH, C4), 39.2 (CH2, C6′), 40.1 [CH2, C8′ (10′) or C4′ (9′)], 50.2 (CH, C2′), 53.3 (CH2, NCH2CH3), 53.7 [CH2, C2(6)]. GC/MS (EI), m/e (%); main ions: 247 (M·+, 10), 233 (18), 232 (100), 58 (23). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C17H29N+H+]: 248.2373, found: 248.2374.

Synthesis of 2-(pyridin-4-ylmethyl)adamantan-2-ol, 14

To a solution of 4-picoline (3.1 g, 33.3 mmol) in anhydrous THF (25 mL) at −20 °C, n-butyllithium (13.4 mL, 2.5 N in hexanes, 33.5 mmol) was added dropwise. When the addition was over, the mixture was allowed to reach room temperature and a solution of 2-adamantanone (5.0 g, 33.3 mmol) in anhydrous THF (18 mL) was added dropwise during 15 minutes and left stirring for 2 hours. After quenching with water (5 mL), the THF was evaporated. Diethyl ether was added, layers were separated and the aqueous one was washed with water (1 × 15 mL) and extracted with HCl 5N (3 × 15 mL). The aqueous extract was basified with solid Na2CO3. A white solid precipitated that was filtered, washed with water and dried to give pure 14 (7.3 g, 90% yield), mp 202–203 °C (dec.). IR (ATR) 3721, 3215, 2906, 1691, 1603, 1423, 1345, 1236, 1170, 1001, 958, 829, 753 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.53 [d, J = 12.6 Hz, 2 H, 4(9)-Ha or 8(10)-Ha], 1.62 [broad s, 2 H, 1(3)-H], 1.74–1.85 (complex signal, 5 H, 6-H2, 8(10)-Ha or 4(9)-Ha and 5-H or 7-H], 1.91 (m, 1 H, 7-H or 5-H), 2.15 [broad d, J = 10.8 Hz, 2 H, 8(10)-Hb or 4(9)-Hb], 2.24 (broad d, J = 12.6 Hz, 2 H, 4(9)-Hb or 8(10)-Hb], 3.04 (s, 2 H, 2C-CH2), 7.34 [m, 2 H, 3′ (5′)-H], 8.39 [m, 2 H, 2′ (6′)-H]. 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ 28.8 (CH) and 28.9 (CH) (C5 and C7), 33.9 (CH2) and 35.5 (CH2) [C4(9) and C8(10)], 38.0 [CH, C1(3)], 39.6 (CH2, C6), 44.6 (CH2, 2C-CH2), 76.1 (C, 2C), 128.0 [CH, C3′ (5′)], 149.1 [CH, C2′ (6′)], 150.4 (C, C4′). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C16H21NO+H+]: 244.1696, found: 244.1693.

Synthesis of 2-(piperidin-4-ylmethyl)adamantan-2-ol hydrochloride, 15·HCl

A solution of 14 (3.0 g, 12.3 mmol) and conc HCl (6 mL, 72 mmol) in methanol (50 mL), was hydrogenated over PtO2 (50 mg) at room temperature and 1 atm for 5 days in which H2 was recharged. After filtration in order to remove the catalyst, it was concentrated under reduced pressure, obtaining the desired product 15·HCl as a white solid in quantitative yield. mp > 300 °C (dec.) IR (ATR) 3407, 2901, 2845, 2789, 2729, 2516, 2156, 1595, 1448, 1350, 1282, 1254, 1127, 1044, 1019, 1006, 958, 930 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.47 [m, 2 H, 3′ (5′)-Hax], 1.54 [m, 2 H, 4(9)-Ha or 8(10)-Ha], 1.68 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2 H, 2C-CH2), 1.70–1.94 (complex signal, 11 H, 5-H, 7-H, 4′-H, 1(3)-H, 6-H2, 4(9)-Hb or 8(10)-Hb and 8(10)-Ha or 4(9)-Ha], 2.02 [dm, J = 13.2 Hz, 2 H, 3′ (5′)-Heq], 2.29 [dm, J = 12.0 Hz, 2 H, 8(10)-Hb or 4(9)-Hb], 2.98 [td, J = 12.4 Hz, J′ = 3.2 Hz, 2 H, 2′ (6′)-Hax], 3.34 [broad d, 2 H, J = 12.4 Hz, 2′ (6′)-Heq]. 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 28.9 (CH) and 29.9 (CH) (C5 and C7), 30.1 (CH, C4′), 32.0 [CH2, C3′ (5′)], 33.8 [CH2, C4(9) or C8(10)], 35.6 [CH2, C8(10) or C4(9)], 38.4 [CH, C1(3)], 39.5 (CH2, C6), 45.1 (CH2, C2-CH2), 45.4 [CH2, C2′ (6′)], 76.4 (CH, C2). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C16H27NO+H+]: 250.2165, found: 250.2170.

Synthesis of 4-[(adamantan-2-ylidene)methyl]piperidine hydrochloride, 16·HCl

SOCl2 (0.42 mL, 5.78 mmol) was slowly added to a solution of 15·HCl (1.0 g, 3.50 mmol) and pyridine (0.84 mL) in dry CH2Cl2 (8 mL) at −60 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at this temperature under argon atmosphere for 30 min and quenched with saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 (1 mL) and the cooling bath was removed. The mixture was poured into diethyl ether-water (90 mL : 20 mL) and the phases were shaken and separated. The aqueous layer was further extracted with diethyl ether twice. The organic phases were joined, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated to give 16 as a white solid in quantitative yield. An analytical sample of the hydrochloride was obtained by adding an excess of Et2O·HCl to a solution of 16 in diethyl ether, mp > 300 °C (dec.). IR (ATR) 3397, 2921, 2845, 2718, 2658, 2541, 2506, 1663, 1625, 1595, 1527, 1469, 1443, 1421, 1241, 1100, 1077, 976, 930, 849, 806 cm−1. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 1.44 [dq, 2 H, J = 4.0 Hz, J′ = 12.6 Hz, 3(5)-Hax], 1.68–1.82 (complex signal, 6 H, 3(5)-Heq, 4′ (10′)-Ha and 8′ (9′)-Ha], 1.87 [broad s, 2 H, 5′ (7′)-H], 1.88–1.96 (complex signal, 6 H, 6′-H2, 4′ (10′)-Hb and 8′ (9′)-Hb], 2.30 (broad s, 1 H, 1′-H), 2.51 (m, 1 H, 4-H), 2.85 (broad s, 1 H, 3′-H), 2.88 [dt, 3 H, J = 12.8 Hz, J = 2.8 Hz, 2(6)-Hax], 3.26 [dm, 2 H, J = 12.8 Hz, 2(6)-Heq], 4.90 (d, 1 H, J = 8.8 Hz, C2′=CH). 13C-NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 29.9 [CH, C5′ (7′)], 31.8 [CH2, C3(5)], 33.2 (CH, C4), 34.1 (CH, C3′), 38.2 (CH2, C6′), 40.2 [CH2, C4′ (10′) or C8′ (9′)], 40.9 [CH2, C8′ (9) ′ or C4′ (10′)], 41.9 (CH, C1′), 45.4 [CH2, C2(6)], 121.1 (CH, C2′=CH), 149.8 (C, C2′). GC/MS (EI), m/e (%); main ions: 231 (M·+, 5), 83 (10), 82 (100), 57 (12). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C16H25N+H+]: 232.2060, found: 232.2062.

Synthesis of 4-[(adamantan-2-yl)methyl]piperidine hydrochloride, 17·HCl

A solution of 16 (230 mg; 1 mmol) in methanol containing few drops of conc HCl, was hydrogenated over Pd/C (5% Pd, 23 mg) at room temperature and 1 atm pressure, for 2 hours. After filtration in order to remove the catalyst, it was concentrated under reduced pressure and the white solid obtained, washed with pentane, giving 17·HCl (183 mg, 68% yield), mp > 278 °C (dec.). IR (ATR) 3397, 2906, 2845, 2718, 2496, 1595, 1448, 1385, 1271, 1100, 1072, 973, 953 cm−1. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 1.35 [m, 2 H, 3(5)-Hax], 1.45 (t, 2 H, J = 7.6 Hz, Ad-CH2-piperidine), 1.56 [d, 2 H, J = 12.8 Hz, 4′ (9′)-Ha or 8′ (10′)-Ha], 1.64 (m, 1 H, 4-H), 1.67 [s, 2 H, 1′ (3′)-H], 1.75–1.98 (complex signal, 14 H, 2′-H, 5′-H, 7′-H, 3(5)-Heq, 8′ (10′)-Hb or 4′ (9′)-Hb, 6′-H2, 8′ (10′)-Ha or 4′ (9′)-Ha], 2.97 [tm, 2 H, J = 12.8 Hz, 2(6)-Hax], 3.37 [dm, 2 H, J = 12.8 Hz, 2(6)-Heq]. 13C-NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 29.5 (CH) and 29.7 (CH) (C5′ and C7′), 30.4 [CH2, C3(5)], 32.4 (CH, C4), 32.6 [CH2, C4′ (9) or C8′ (10′)], 33.4 [CH, C1′ (3′)], 39.4 (CH2, C6′), 40.2 (CH2, Ad-CH2-piperidine), 40.3 [CH2, C8′ (10′) or C4′ (9′)], 41.9 (CH, C2′), 45.4 [CH2, C2(6)]. GC/MS (EI), m/e (%); tr 20.5 min: 233 (M·+, 11), 219 (16), 218 (100), 98 (31), 85 (95), 84 (77), 82 (22), 79 (20), 67 (18), 57 (39), 56 (30), 55 (18). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C16H27N+H+]: 234.2216, found: 234.2215.

4-[(adamantan-2-yl)methyl]-N-methylpiperidine, 18·HCl

In a 250 mL round bottom flask was added 17·HCl (123 mg, 0.5 mmol), NaBH3CN (94.2 mg, 1.5 mmol), formaldehyde (37% aqueous solution, 0.13 mL, 1.5 mmol) and glacial acetic acid (0.1 mL) and left stirring, covered with a CaCl2 tube at 30 °C overnight. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo, the residue was suspended in water (10 mL) and the solution was made basic with aqueous solution of 2 N NaOH and extracted with EtOAc (1×50 mL) and dichloromethane (2 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried, filtered and concentrated under vacuum. The corresponding hydrochloride, 18·HCl, was made by adding an ethereal solution of HCl to a solution of the residue in EtOAc and purified by crystallization from diethyleter (104 mg, 73% yield), mp 265–267 °C. IR (ATR) 3417, 3362, 2906, 2850, 2663, 2546, 1615, 1464, 1451, 1256, 1067, 955 cm−1. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 1.44 (t, 2 H, J = 6.8 Hz, Ad-CH2-piperidine), 1.45 [m, 2 H, 3(5)-Hax], 1.55 [broad d, 2 H, J = 12.8 Hz, 4′ (9′)-Ha or 8′ (10′)-Ha], 1.59 (m, 1 H, 4-H), 1.66 [s, 2 H, 1′ (3′)-H], 1.74–1.82 (complex signal, 6 H, 2′-H, 5′-H or 7′-H, 8(10)-Ha or 4(9′)-Ha, 6′-H2], 1.84–2.00 (complex signal, 7 H, 8(10)-H2 or C4(9)-H2], 7′-H or 5′-H, 3(5)-Heq], 2.83 (s, 3 H, NCH3), 2.70 [broad t, 2 H, J = 12.8 Hz, 2(6)-Hax], 3.47 [broad d, 2 H, J = 12.8 Hz, 2(6)-Heq]. 13C-NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 29.5 (CH) and 29.6 (CH) (C5′ and C7′), 31.3 [CH2, C3(5)], 31.8 (CH, C4), 32.5 [CH2, C4′ (9) or C8′ (10′)], 33.3 [CH, C1′ (3′)], 39.4 (CH2, C6′), 39.9 (CH2, Ad-CH2-piperidine), 40.3 [CH2, C8′ (10′) or C4′ (9′)], 42.0 (CH, C2′), 44.1 (CH3, N-CH3), 56.0 [CH2, C2(6)]. HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C17H29N+H+]: 248.2373, found: 248.2374.

Synthesis of 4-[(adamantan-2-ylidene)methyl]piperidine-1-carboximidamide hydrochloride, 19·HCl

In a 10 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a condenser and a magnetic stirrer, a suspension of amine 16 (131 mg, 0.56 mmol), 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine hydrochloride (86.3 mg, 0.59 mmol), anhydrous triethylamine (0.12 mL, 0.86 mmol) in acetonitrile (3 mL) was prepared. The reaction was heated at 70 °C for 6 hours. The reaction was cooled down and stored at 4 °C overnight. The suspension was filtered out and the filtrate washed with cold pentane obtaining the guanidine 19·HCl as a white solid (131 mg, 88% yield). mp 266–272 °C (dec.). IR (ATR) 3245, 3139, 2901, 2850, 1648, 1614, 1512, 1441, 1342, 1168, 1122, 960 cm−1. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 1.35 [m, 2 H, 3(5)-Hax], 1.65–1.79 (complex signal, 6 H, 3(5)-Heq, 4′ (10′)-Ha and 8′ (9′)-Ha], 1.88 [broad s, 2 H, 5′ (7′)-H], 1.88–1.96 (complex signal, 6 H, 6′-H2, 4′ (10′)-Hb and 8′ (9′)-Hb], 2.29 (broad s, 1 H, 1′-H), 2.58 (m, 1 H, 4-H), 2.87 (broad s, 1 H, 3′-H), 3.12 [dt, 3 H, J = 13.6 Hz, J = 2.8 Hz, 2(6)-Hax], 3.85 [dm, 2 H, J = 13.6 Hz, 2(6)-Heq], 4.90 (d, 1 H, J = 8.8 Hz, C2′=CH). 13C-NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 30.0 [CH, C5′ (7′)], 33.4 [CH2, C3(5)], 34.1 (CH, C3′), 34.2 (CH, C4), 38.2 (CH2, C6′), 40.2 [CH2, C4′ (10′) or C8′ (9′)], 40.9 [CH2, C8′ (9) ′ or C4′ (10′)], 41.9 (CH, C1′), 46.9 [CH2, C2(6)], 121.0 (CH, C2′=CH), 149.7 (C, C2′), 157.5 (C, C=NH). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C17H27N3+H+]: 274.2278, found: 274.2275.

4-[(adamantan-2-yl)methyl]piperidine-1-carboximidamide hydrochloride, 20·HCl

In a 10 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a condenser and a magnetic stirrer, a suspension of amine 17·HCl (83 mg, 0.3 mmol), 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine hydrochloride (54.2 mg, 0.37 mmol), anhydrous triethylamine (0.1 mL) in acetonitrile (3 mL) was prepared. The reaction was heated at 70 °C for 6 hours. The reaction was cooled down and stored at 4 °C overnight. The suspension was filtered out and the filtrate washed with cold acetonitrile obtaining the guanidine 20·HCl as a white solid (60 mg, 64% yield). mp 268–270 °C (dec.). IR (ATR) 3306, 3220, 3103, 2906, 2845, 1633, 1453, 1347, 1160, 1092, 963, 821, 723 cm−1. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 1.19 [dq, 2 H, J = 13.6 Hz, J′ = 4.0 Hz, 3(5)-Hax], 1.32 (t, 2 H, J = 7.6 Hz, Ad-CH2-piperidine), 1.55 [broad d, 2 H, J = 12.4 Hz, 4′ (9′)-Ha or 8′ (10′)-Ha], 1.64 (m, 1 H, 4-H), 1.67 [broad s, 2 H, 1′ (3′)-H], 1.75–1.98 [complex signal, 13 H, 3(5)-Heq, 2′-H, 5′-H, 6′-H2, 7′-H, 4′ (9′)-Hb or 8′ (10′)-Hb, 4′ (9′)-H2 or 8′ (10′)-H2], 3.06 [td, 2 H, J = 13.6 Hz, J′ = 2.8 Hz, 2(6)-Hax], 3.87 [dm, 2 H, J = 13.6 Hz, 2(6)-Heq]. 13C-NMR (100.6 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 29.5 (CH) and 29.7 (CH) (C5′ and C7′), 32.6 [CH2, C4′ (9) or C8′ (10′)], 33.1 [CH2, C3(5)], 33.4 [CH, C1′ (3′)], 33.9 (CH, C4), 39.4 (CH2, C6′), 40.3 (CH2, Ad-CH2-piperidine), 40.4 [CH2, C8′ (10′) or C4′ (9′)], 42.0 (CH, C2′), 47.2 [CH2, C2(6)], 157.5 (C, C=N). HRMS-ESI+ m/z [M+H]+ calcd for [C17H29N3+H+]: 276.2434, found: 276.2437.

Plasmid, mRNA synthesis, and microinjection of oocytes

The cDNA encoding the influenza A/Udorn/72 (A/M2) was inserted into pSUPER vector for the expression on oocyte plasma membrane. A/M2 S31N and A/M2 V27A mutants were generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). The synthesis of mRNA and microinjection of oocytes have been described previously.67

Two-electrode voltage clamp analysis

Macroscopic membrane current was recorded 24–72 hours after injection as described previously.31 Oocytes were perfused at room temperature in Barth’s solution containing (in mM) 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 0.3 NaNO3, 0.71 CaCl2, 0.82 MgCl2, and 15 HEPES for pH 8.5 or 15 MES for pH 5.5 at a rate of 2 mL/min. The tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO and applied (100 μM) at pH 5.5 when the inward current reaches maximum. The compounds were applied for 2 min, and residual membrane current was compared with the membrane current before the application of compounds. The compounds were typically applied for 2 min, and residual membrane current was compared with the membrane current before the application of compounds. Membrane currents were recorded at −20 mV and analyzed with pCLAMP 10.0 software package (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA).

Antiviral assays

The anti-influenza virus activity in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells was determined by plaque reduction (PRA) and virus yield assays. For the PRA, influenza virus A/HK/7/87 (A/H3N2) was incubated (1 h at 4°C) with different concentrations of the compounds, and then added to confluent MDCK cells in 12-well plates. After 1 h incubation at 35°C, excess virus was removed and replaced by fresh medium containing the compounds and 0.8% agarose. After 72 h incubation, plaques were visualized by cell fixation with 3.7% formaldehyde and staining with 0.1% crystal violet. For the virus yield assay, MDCK cells grown in 96-well plates were infected with influenza virus A/HK/7/87, and at the same time the test compounds were added in serial dilutions. After 24 h incubation at 35 °C, supernatants were harvested to determine the virus yield by RT-qPCR.63,68 In parallel, mock-infected cell cultures were used to determine the compounds’ cytotoxicity. After 72 h incubation at 35 °C, cell viability was measured by the formazan-based MTS assay and the OD values were used to calculate the compound concentrations causing 50% cytotoxicity (CC50).68

The PRA with A/WSN/33 N31S/V27A (H1N1) virus was carried out similarly as previously described.32 Briefly, MDCK cells monolayers in 6-well plates were infected with virus (~100 PFU/well). After adding the inoculums, cells were kept in 4 °C for 1 h to synchronize the infection, then cells were moved to 37 °C incubator for 1 h. The inoculums were removed, and the cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The cells were then overlaid with DMEM containing 1.2% Avicel microcrystalline cellulose (FMC BioPolymer, Philadelphia, PA) and NAT (2.0 μg/ml). To examine the effect of the drugs on plaque formation, at 46 h after infection, the monolayers were fixed and stained with 0.2% crystal violet in 20% methanol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M.B.-X. thanks the Institute of Biomedicine of the Universitat de Barcelona (IBUB) for a PhD grant. The authors thank the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (FPU fellowship to E.T.; grant SAF2014-57094-R to S.V.). L.N. acknowledges financial support from the Geconcerteerde Onderzoeksacties (GOA/15/019/TBA), and technical assistance from W. van Dam. J. W. acknowledges the support from NIH grant AI119187. We thank Prof. W. F. DeGrado for his expert advice.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Amt

amantadine

- ATR

Attenuated Total Reflectance

- MDCK

Madin-Darby Canine Kidney

- MTS

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium

- RT-qPCR

quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- TEVC

two-electrode voltage clamp

- wt

wild-type

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The supporting information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Additional electrophysiological experiments. Plaque reduction assay with A/WSN/33 N31S/V27A (H1N1) virus. Elemental analysis data of the new compounds. (PDF)

Molecular formula string and some data (CSV)

References

- 1.Vanderlinden E, Naesens L. Emerging antiviral strategies to interfere with influenza virus entry. Med Res Rev. 2014;34:301–339. doi: 10.1002/med.21289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto LH, Lamb RA. The M2 proton channels of influenza A and B viruses. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8997–9000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Qiu JX, Soto CS, DeGrado WF. Structural and dynamic mechanisms for the function and inhibition of the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong M, DeGrado WF. Structural basis for proton conduction and inhibition by the influenza M2 protein. Protein Sci. 2012;21:1620–1633. doi: 10.1002/pro.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei C, Pohorille A. Activation and proton transport mechanism in influenza A M2 channel. Biophys J. 2013;105:2036–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawano K, Yano Y, Matsuzaki K. A dimer is the minimal proton-conducting unit of the influenza A virus M2 channel. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:2679–2691. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georgieva ER, Borbat PP, Norman HD, Freed JH. Mechanism of influenza A M2 transmembrane domain assembly in lipid membranes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11757. doi: 10.1038/srep11757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreas LB, Reese M, Eddy MT, Gelev V, Ni QZ, Miller EA, Emsley L, Pintacuda G, Chou JJ, Griffin RG. Structure and mechanism of the influenza-A M218-60 dimer of dimers. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14877–14886. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomaston JL, Alfonso-Prieto M, Woldeyes RA, Fraser JS, Klein ML, Fiorin G, DeGrado WF. High-resolution structures of the M2 channel from influenza A virus reveal dynamic pathways for proton stabilization and transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:14260–14265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518493112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei C, Pohorille A. M2 proton channel: toward a model of a primitive proton pump. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 2015;45:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s11084-015-9421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu R, Liu LA, Wei D. Drug inhibition and proton conduction mechanisms of the influenza A M2 proton channel. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;827:205–226. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9245-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong G, Peng C, Luo J, Wang C, Han L, Wu B, Ji G, He H. Adamantane-resistant influenza A viruses in the world (1902–2013): frequency and distribution of M2 gene mutations. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiore AE, Fry AM, Shay DK, Gubareva LV, Bresee JS, Uyeki TM. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza - recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gleed ML, Busath DD. Why bound amantadine fails to inhibit proton conductance according to simulations of the drug-resistant influenza A M2 (S31N) J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:1225–1231. doi: 10.1021/jp508545d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleed ML, Ioannidis H, Kolocouris A, Busath DD. Resistance-mutation (N31) effects on drug orientation and channel hydration in amantadine-bound influenza A M2. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:11548–11559. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b05808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balannik V, Carnevale V, Fiorin G, Levine BG, Lamb RA, Klein ML, DeGrado WF, Pinto LH. Functional studies and modeling of pore-lining residue mutants of the influenza A virus M2 ion channel. Biochemistry. 2010;49:696–708. doi: 10.1021/bi901799k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki H, Saito R, Masuda H, Oshitani H, Sato M, Sato I. Emergence of amantadine-resistant influenza A viruses: Epidemiological study. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s10156-003-0262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito R, Sakai T, Sato I, Sano Y, Oshitani H, Sato M, Suzuki H. Frequency of amantadine-resistant influenza A viruses during two seasons featuring cocirculation of H1N1 and H3N2. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2164–2165. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.2164-2165.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furuse Y, Suzuki A, Oshitani H. Large-scale sequence analysis of M gene of influenza A viruses from different species: Mechanisms for emergence and spread of amantadine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4457–4463. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00650-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durrant MG, Eggett DL, Busath DD. Investigation of a recent rise of dual amantadine-resistance mutations in the influenza A M2 sequence. BMC Genetics. 2015;16(Suppl 2):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-16-S2-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abed Y, Goyette N, Boivin G. Generation and characterization of recombinant influenza A (H1N1) viruses harboring amantadine resistance mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:556–559. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.556-559.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duque MD, Valverde E, Barniol M, Guardiola S, Rey M, Vázquez S. Inhibitors of the M2 channel of the influenza A virus. In: Muñoz-Torrero D, editor. Recent Advances in Pharmaceutical Sciences. Transworld Research Network; Kerala (India): 2011. pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Li F, Ma C. Recent progress in designing inhibitors that target the drug-resistant M2 proton channels from the influenza A viruses. Biopolymers. 2015;104:291–309. doi: 10.1002/bip.22623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Cady SD, Balannik V, Pinto LH, DeGrado WF, Hong M. Discovery of spiro-piperidine inhibitors and their modulation of the dynamics of the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8066–8076. doi: 10.1021/ja900063s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu W, Zeng S, Li C, Jie Y, Li Z, Chen L. Identification of hits as matrix-2 protein inhibitors through the focused screening of a small primary amine library. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3831–3834. doi: 10.1021/jm901664a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duque MD, Ma C, Torres E, Wang J, Naesens L, Juárez-Jiménez J, Camps P, Luque FJ, DeGrado WF, Lamb RA, Pinto LH, Vázquez S. Exploring the size limit of templates for inhibitors of the M2 ion channel of influenza A virus. J Med Chem. 2011;54:2646–2657. doi: 10.1021/jm101334y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Ma C, Balannik V, Pinto LH, Lamb RA, DeGrado WF. Exploring the requirements for the hydrophobic scaffold and polar amine in inhibitors of M2 from influenza A virus. ACS Med Chem Let. 2011;2:307–312. doi: 10.1021/ml100297w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao X, Zhang ZW, Cui W, Chen S, Zhou Y, Dong J, Jie Y, Wan J, Xu Y, Hu W. Identification of camphor derivatives as novel M2 ion channel inhibitors of influenza A virus. Med Chem Commun. 2015;6:727–731. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu S, Huang J, Gazzarrini S, He S, Chen L, Li J, Xing L, Li C, Chen L, Neochoritis CG, Liao GP, Zhou H, Dömling A, Moroni A, Wang W. Isocyanides as influenza A virus subtype H5N1 wild-type M2 channel inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:1837–1845. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tzitzoglaki C, Wright A, Freudenberger K, Hoffmann A, Tietjen I, Stylianakis I, Kolarov F, Fedida D, Schmidtke M, Gauglitz G, Cross TA, Kolocouris A. Binding and proton blockage by amantadine variants of the influenza M2WT and M2S31N explained. J Med Chem. 2017;60:1716–1733. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balannik V, Wang J, Ohigashi Y, Jing X, Magavern E, Lamb RA, DeGrado WF, Pinto LH. Design and pharmacological characterization of inhibitors of amantadine-resistant mutants of the M2 ion channel of influenza A virus. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11872–11882. doi: 10.1021/bi9014488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Ma C, Fiorin G, Carnevale V, Wang T, Hu F, Lamb RA, Pinto LH, Hong M, Klein ML, DeGrado WF. Molecular dynamics simulation directed rational design of inhibitors targeting drug-resistant mutants of influenza A virus M2. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12834–12841. doi: 10.1021/ja204969m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rey-Carrizo M, Torres E, Ma C, Barniol-Xicota M, Wang J, Wu Y, Naesens L, DeGrado WF, Lamb RA, Pinto LH, Vazquez S. Azatetracyclo[5.2.1.15,8.01,5]undecane derivatives: from wild-type inhibitors of the M2 ion channel of influenza A virus to derivatives with potent activity against the V27A mutant. J Med Chem. 2013;56:9265–9274. doi: 10.1021/jm401340p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rey-Carrizo M, Barniol-Xicota M, Ma C, Frigolé-Vivas M, Torres E, Naesens L, Llabrés S, Juárez-Jiménez J, Luque FJ, DeGrado WF, Lamb RA, Pinto LH, Vázquez S. Easily accessible polycyclic amines that inhibit the wild-type and amantadine-resistant mutants of the M2 channel of influenza A virus. J Med Chem. 2014;57:5738–5747. doi: 10.1021/jm5005804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rey-Carrizo M, Gazzarrini S, Llabrés S, Frigolé-Vivas M, Juárez-Jiménez J, Font-Bardia M, Naesens L, Moroni A, Luque FJ, Vázquez S. New polycyclic dual inhibitors of the wild type and the V27A mutant M2 channel of the influenza A virus with unexpected binding mode. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;96:318–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu Y, Musharrafieh R, Ma C, Zhang J, Smee DF, DeGrado WF, Wang J. An M2-V27A channel blocker demonstrates potent in vitro and in vivo antiviral activities against amantadine-sensitive and –resistant influenza A viruses. Antiviral Res. 2017;140:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Wu Y, Ma C, Fiorin G, Wang J, Pinto LH, Lamb RA, Klein ML, DeGrado WF. Structure and inhibition of the drug-resistant S31N mutant of the M2 ion channel of influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1315–1320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216526110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Ma C, Wang J, Jo H, Canturk B, Fiorin G, Pinto LH, Lamb RA, Klein ML, DeGrado WF. Discovery of novel dual inhibitors of the wild-type and the most prevalent drug-resistant mutant, S31N, of the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. J Med Chem. 2013;56:2804–2812. doi: 10.1021/jm301538e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams JK, Tietze D, Wang J, Wu Y, DeGrado WF, Hong M. Drug-induced conformational and dynamical changes of the S31N mutant of the influenza M2 proton channel investigated by solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9885–9897. doi: 10.1021/ja4041412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Y, Canturk B, Jo H, Ma C, Gianti E, Fiorin G, Pinto LH, Lamb RA, Klein ML, Wang J, DeGrado WF. Flipping in the pore: Discovery of dual inhibitors that bind in different orientations to the wild-type versus the amantadine-resistant S31N mutant of the influenza A virus M2 proton channel. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:17987–17995. doi: 10.1021/ja508461m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li F, Ma C, DeGrado WF, Wang J. Discovery of highly potent inhibitors targeting the predominant drug-resistant S31N mutant of the influenza A virus M2 proton channel. J Med Chem. 2016;59:1207–1216. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li F, Ma C, Hu Y, Wang Y, Wang J. Discovery of potent antivirals against amantadine-resistant influenza A viruses by targeting the M2-S31N proton channel. ACS Infect Dis. 2016;2:726–733. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jalily PH, Eldstrom J, Miller SC, Kwan DC, Tai SSH, Chou D, Niikura M, Tietjen I, Fedida D. Mechanisms of action of novel influenza A/M2 viroporin inhibitors derived from hexamethylene amiloride. Mol Pharmacol. 2016;90:80–95. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.102731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li F, Hu Y, Wang Y, Ma C, Wang J. Expeditious lead optimization of isoxale-containing influenza A virus M2-S31N inhibitors using the Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. J Med Chem. 2017;60:1580–1590. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zoidis G, Kolocouris N, Foscolos GB, Kolocouris A, Fytas G, Karayannis P, Padalko E, Neyts J, De Clercq E. Are the 2-isomers of the drug rimantadine active anti-influenza A agents? Antivir Chem Chemother. 2003;14:153–164. doi: 10.1177/095632020301400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kolocouris A, Tzitzoglaki C, Johnson FB, Zell R, Wright AK, Cross TA, Tietjen I, Fedida D, Busath DD. Aminoadamantanes with persistent in vitro efficacy against H1N1 (2009) influenza A. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4629–4639. doi: 10.1021/jm500598u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C, Takeuchi K, Pinto LH. Ion channel activity of influenza A virus M2 protein: characterization of the amantadine block. J Virol. 1993;67:5585–5594. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5585-5594.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Astrahan P, Kass I, Cooper MA, Arkin IT. A novel method of resistance for influenza against a channel-blocking antiviral drug. Proteins. 2004;55:251–257. doi: 10.1002/prot.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leonov H, Astrahan P, Krugliak M, Arkin IT. How do aminoadamantanes block the influenza M2 channel, and how does resistance develop? J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9903–9911. doi: 10.1021/ja202288m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Togo H, Aoki M, Kuramochi M, Yokoyama M. Radical decarboxylative alkylation onto heteroaromatic bases with trivalent iodine compounds. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1993:2417–2427. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stamatiou G, Foscolos GB, Fytas G, Kolocouris A, Kolocouris N, Pannecouque C, Witvrouw M, Padalko E, Neyts J, De Clercq E. Heterocyclic rimantadine analogues with antiviral activity. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:5485–5492. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cady SD, Schmidt-Rohr K, Wang J, Soto CS, DeGrado WF, Hong M. Structure of the amantadine binding site of influenza M2 proton channels in lipid bilayers. Nature. 2010;463:689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature08722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolocouris A, González Outeriño J, Anderson JE, Fytas G, Foscolos GB, Kolocouris N. The effect of neighboring 1- and 2-adamantyl group substitution on the conformations and stereodynamics of N-methylpiperidine. Dynamic NMR spectroscopy and molecular mechanics calculations. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4989–4997. doi: 10.1021/jo0016677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolocouris A, Tataridis D, Fytas G, Mavromoustakos T, Foscolos GB, Kolocouris N, De Clercq E. Synthesis of 2-(2-adamantyl)piperidines and structure anti-influenza virus A activity relationship study using a combination of NMR spectroscopy and molecular modeling. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:3465–3470. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00631-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mariani E, Schenone P, Bondavalli F, Lampa E, Marmo E. (±)-1-(Adamantan-2-yl)-2-propanamine and other amines derived from 2-adamantanone. Il Farmaco. 1980;35:430–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Álvarez-Manzaneda E, Chahboun R, Álvarez E, Tapia R, Álvarez-Manzaneda R. Enantioselective total synthesis of cytotoxic taiwaniaquinones A and F. Chem Commun. 2010;46:9244–9246. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03763j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gianti E, Carnevale V, DeGrado WF, Klein ML, Fiorin G. Hydrogen-bonded water molecules in the M2 channel of the influenza A virus guide the binding preferences of ammonium-based inhibitors. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:1173–1183. doi: 10.1021/jp506807y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pielak RM, Chou JJ. Solution NMR structure of the V27A drug resistant mutant of influenza A M2 channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;401:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gu RX, Liu LA, Wang YH, Xu Q, Wei DQ. Structural comparison of the wild-type and drug-resistant mutants of the influenza A M2 proton channel by molecular dynamics simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:6042–6051. doi: 10.1021/jp312396q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jing X, Ma C, Ohigashi Y, Oliveira FA, Jardetzky TS, Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Functional studies indicate amantadine binds to the pore of the influenza A virus M2 proton-selective ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10967–10972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804958105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Torres E, Duque MD, Vanderlinden E, Ma C, Pinto LH, Camps P, Froeyen M, Vázquez S, Naesens L. Role of the viral hemagglutinin in the anti-influenza virus activity of newly synthesized polycyclic amine compounds. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.For a recent set of compounds that seem to behave similarly see: Dong J, Chen S, Li R, Cui W, Jiang H, Ling Y, Yang Z, Hu W. Imidazole-based pinanamine derivatives: discovery of dual inhibitors of the wild-type and drug-resistant mutant of the influenza A virus. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;108:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.12.013.

- 63.Stevaert A, Dallocchio R, Dessì A, Pala N, Rogolino D, Sechi M, Naesens L. Mutational analysis of the binding pockets of the diketo acid inhibitor L-742,001 in the influenza virus PA endonuclease. J Virol. 2013;87:10524–10538. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00832-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gu RX, Liu LA, Wei DQ. Structural and energetic analysis of drug inhibition of the influenza A M2 proton channel. Trends Pharm Sci. 2013;34:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Nguyen H, Nguyen HT, Le LT. Investigation of the free energy profiles of amantadine and rimantadine in the AM2 binding pocket. Eur Biophys J. 2016;45:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s00249-015-1077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.See the Supporting Information for elemental analysis data.

- 67.Ma C, Soto CS, Ohigashi Y, Taylor A, Bournas V, Glawe B, Udo MK, DeGrado WF, Lamb RA, Pinto LH. Identification of the pore-lining residues of the BM2 ion channel protein of influenza B virus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15921–15931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710302200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vanderlinden E, Göktas F, Cesur Z, Froeyen M, Reed ML, Russell CJ, Cesur N, Naesens L. Novel inhibitors of influenza virus fusion: structure-activity relationship and interaction with the viral hemagglutinin. J Virol. 2010;84:4277–4288. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02325-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.