Abstract

An enantioselective total synthesis of spliceostatin G has been accomplished. The synthesis involved a Suzuki cross-coupling reaction as the key step to construct spliceostatin G. The functionalized tetrahydropyran ring was constructed from commercially available optically active tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal. Other key reactions include highly stereoselective Claisen rearrangement, 1,4 addition of MeLi to install C8 methyl group and reductive amination to incorporate the C10 amine functionality of spliceostatin G. Our biological evaluation of synthetic spliceostatin G and its methyl ester revealed that it does not inhibit splicing in vitro.

Graphical abstract

In mammalian cells, the splicing of pre-mRNAs is a fundamental process for gene expression.1,2 Splicing is carried out by a complex ribonuclear machinery, called spliceosome which upon recognition of splicing signal, catalyzes the removal of non-coding sequences (introns) and assembles protein coding sequences (exons) to form messenger mRNA prior to export and translation.3,4 These transcription and translation steps are generally very complicated. Recent studies have revealed that splicing is pathologically altered in many different ways in cancer cells.5,6 Therefore, manipulation or inhibition of splicing events by targeting spliceosome may be an effective strategy for anticancer drug development. Among strategies modulation of spliceosome to target cancer therapeutically has become an area of significant interest. Pladienolides (pladienolide B, 1, Figure 1) isolated from Streptomyces, were shown to be potently cytotoxic.7,8 They inhibit spliceosome by binding to SF3B subunit of spliceosome.9,10 While pladienolides are unsuitable for clinical use, a semisynthetic derivative E707, 2 underwent clinical trials.11,12 Subsequently, other natural products, such as FR901464, 3, and its methylated derivative spliceostatin A, 4 were shown to potently inhibit spliceosome through binding to SF3B subunit of spliceosome.13,14 Total synthesis and further design of structural isomers were pursued for these natural products to improve stability and reduce structural complexities of these agents. Recently,15,16,17 He and co-workers reported isolation and structural studies of a series of spliceostatin class of natural products from the fermentation broth FERM BP-3421 of Burkholderia sp.18 Among these natural products, a less complex structure, spliceostatin G was isolated and full structure of spliceostatin G was confirmed by detailed 1H- and 13C-NMR studies.18 Spliceostatin G did not exhibit potent cytotoxicity inherent to other spliceostatins. Spliceostatin G does not contain epoxy alcohol on a tetrahydropyran framework or 5,6-dihydro-α-pyrone subunit present in more active natural products like spliceostatins A and E.18 As part of continuing interests in the chemistry and biology of spliceostatins, we have devised an enantioselective synthesis of spliceostatin G using readily available tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal as the key starting material. Current synthesis will provide ready access to highly functionalized tetrahydropyran and the diene frameworks of spliceostatins.

Figure 1.

Structures of pladienolide B, E707, FR901464, spliceostatins A and G

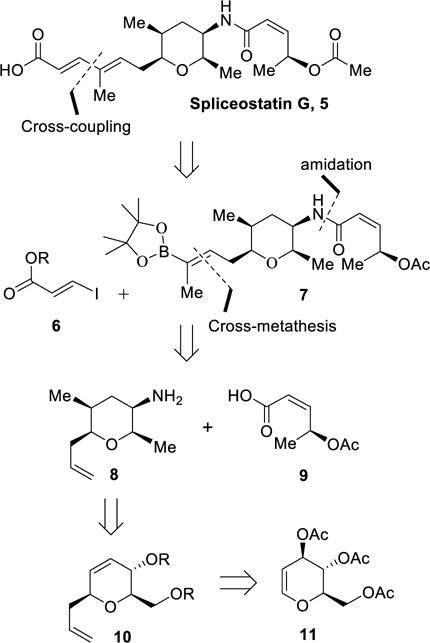

Our strategy for an enantioselective synthesis of spliceostatin G is shown in Scheme 1. To construct the diene component of spliceostatin G we planned a Suzuki cross-coupling reaction between the boronate segment 7 and iodoacrylate 6 at a late stage of the synthesis. The boronate derivative 7 would be obtained by a cross-metathesis reaction of amide derivatives of olefin 8 and commercially available pinacol boronate. Coupling of amine-functionality of 8 with acid 9 would provide the requisite amide for cross-metathesis. The functionalized tetrahydropyran ring 8 could be constructed from dihydropyran derivative 10. Optically active synthesis of this dihydropyran derivative would be carried out from commercially available tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal 11.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthesis of Spliceostatin G

The synthesis of dihydropyran derivative 12 was carried out in multigram scale from commercially available tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal 11 as reported in the literature.19 This was subjected to heating in a sealed tube in toluene at 190 °C for 18 h to provide the Claisen rearrangement product, the corresponding aldehyde. Wittig olefination of the aldehyde with methylene-triphenylphosphorane at 0 °C afforded dihydropyran derivative 13 in 90% yield. The removal of the silyl group was carried out by exposure to nBu4N+F− (TBAF) in THF at 0 °C to 23 °C for 12 h. The resulting alcohol was initially treated with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride in pyridine at 23 °C for 12 h to furnish a mixture (6 : 1) of tosylate derivatives 14 and 15. For regioselective formation of primary sulfonate derivative, we chose a sterically bulkier 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (TPSCI). Reaction of diol with TPSCl in pyridine at 0 °C to 23 °C for 24 h afforded primary sulfonate derivative 16 in 92% yield. Reduction of sulfonate 16 by LAH in THF at 0 °C to 65 °C for 1 h provided the reduction product, the methyl derivative. Oxidation of the resulting allylic alcohol with Dess-Martin periodinane at 0 °C to 23 °C for 1.5 h furnished enone derivative 17 in 80% yield. For stereoselective installation of C5-methyl group, we carried out a 1,4-addition as developed by us previously.17 Thus, treatment of 17 with MeLi in the presence of CuBr•Me2S complex at −78 °C for 2 h provided dihydro-2H-pyranone 18 in excellent yield and excellent diastereoselectivity (25:1 by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR analysis).

Elaboration of dihydropyranone 18 to boronate derivative 7 is shown in Scheme 3. A substrate control stereoselective reduction of ketone 18 with ammonium acetate and NaBH(OAc)3 in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at 23 °C for 12 h afforded primary amine 8 with high diastereoselectivity (96:4 by 1H-NMR analysis).17,20 Coupling of optically active acid 9 and amine 8 using HATU in the presence of diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) resulted in amide derivative 19 in 85% yield. Cross-metathesis of allyl derivative 19 with commercially available pinacol boronate 20 in the presence of Grubb’s 2nd generation catalyst (10%) in 1,2-dichloroethane at 80 °C for 1 h afforded boronate derivative 7 in 41% yield.21,22,23

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of boronate derivative 7

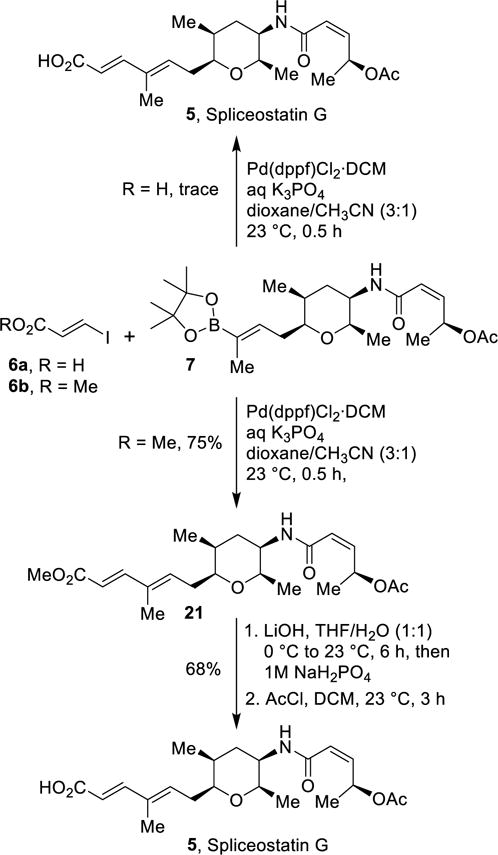

The synthesis of spliceostatin G is shown in Scheme 4. Initially, we conducted Suzuki coupling of boronate 7 and iodocarboxylic acid 6a using Pd(dppf)Cl2•DCM catalyst (20 mol%) in the presence of aqueous K3PO4 in a mixture of dioxane and acetonitrile at 23 °C for 30 min. However, this condition only provided trace amount of coupling product spliceostatin G. We have also carried out this coupling using Pd(Ph3P)4 catalyst (10 mol%) in the presence of Cs2CO3 at 55 °C. This condition only provided trace amount of desired product.24 We then carried out this Suzuki reaction25 with methyl iodoacrylate 6b using Pd(dppf)2Cl2•DCM (20 mol%) catalyst in the presence of aqueous K3PO4 at 23 °C for 30 min to furnish coupling product 21 in 75% yield after silica gel chromatography. The methyl ester 21 was converted to spliceostatin G by saponification with aqueous LiOH in THF at 23 °C for 6 h, followed by reaction of the resulting hydroxyl acid with acetyl chloride in CH2Cl2 at 23 °C for 3 h. Spliceostatin G was obtained in 68% yield over two-steps. The 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR of our synthetic spliceostatin G {[α]D23−71.7 (c 0.53, CHCl3)26 are in full agreement with the reported spectra of natural spliceostatin G.18

Scheme 4.

The synthesis of spliceostatin G.

The biological properties of synthetic spliceostatin G (5) and the precursor 21 were evaluated in an in vitro splicing system as previously described.27 (Figure 2). Neither compound showed inhibition of splicing in this system, even at 100 μM concentration. In contrast, spliceostatin A in the same assay shows strong splicing inhibition. This result is consistent with previous reports showing that spliceostatin G (5) does not affect the growth of several cancer cell lines.18

Figure 2.

Impact of spliceostatin G on in vitro splicing. Average splicing efficiency relative to inhibitor concentration normalized to DMSO control. SSG, spliceostatin G; compound 21; SSA, spliceostatin A.

In summary, we have achieved an enantioselective synthesis of spliceostatin G and confirmed the assignment of relative and absolute stereochemistry of spliceostatin G. The synthesis involved a Suzuki cross-coupling reaction as the key step. Enantioselective synthesis of the functionalized tetrahydropyran ring was achieved from commercially available optically active tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal using a highly stereoselective Claisen rearrangement.

A cross-metathesis of commercially available pinacol boronate using Grubbs’ catalyst provided the vinyl boronate derivative for the cross coupling reaction with iodoacrylic acid. The other stereoselective transformations include highly stereoselective 1,4 addition to construct C8 methyl group and reductive amination to incorporate the C10 amine functionality of spliceostatin G. The synthesis is convergent and amenable to the synthesis of structural variants. We have also evaluated spliceosome inhibitory activity of spliceostatin G and compared its activity with spliceostatin A. Spliceostatin G does not inhibit in vitro splicing assembly or chemistry. The design and synthesis of structural variants of spliceostatins are in progress. These analogs will be important to clarify the link between splicing inhibition and changes in cellular function induced by these remarkable compounds.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of dihydropyranone 18

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the National Institutes of Health and Purdue University is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Margherita Brindisi (Purdue University) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Available General experimental procedures, characterization data for all new products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Wahl MC, Will CL, Lührmann R. Cell. 2009;136:701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roybal GA, Jurica MS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6664–6672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Will CL, Luhrmann R. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rymond B. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:533–535. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0907-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Alphen RJ, Wiemer EA, Burger H, Eskens FA. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:228–232. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper TA, Wan L, Dreyfuss G. Cell. 2009;136:777–793. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakai T, Sameshima T, Matsufuji M, Kawamura N, Dobashi K, Mizui Y. J Antibiot. 2004;57:173–179. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakai T, Asai N, Okuda A, Kawamura N, Mizui Y. J Antibiot. 2004;57:180–187. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotake Y, Sagane K, Owa T, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shimizu H, Uesugi M, Ishihama Y, Iwata M, Mizui Y. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoi A, Kotake Y, Takahashi K, Kadowaki T, Matsumoto Y, Minoshima Y, Sugi NH, Sagane K, Hamaguchi M, Iwata M, Mizui Y. FEBS J. 2011;278:4870–4880. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato M, Muguruma N, Nakagawa T, Okamoto K, Kimura T, Kitamura S, Yano H, Sannomiya K, Goji T, Miyamoto H, Okahisa T, Mikasa H, Wada S, Iwata M, Takayama T. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:110–116. doi: 10.1111/cas.12317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler MA. In: Natural Product-Derived Compounds in Late State Clinical Development at the End of 2008. Buss A, Butler M, editors. The Royal Chemical Society of Chemistry; Cambridge, UK: 2009. pp. 321–354. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaida D, Motoyoshi H, Tashiro E, Nojima T, Hagiwara M, Ishigami K, Watanabe H, Kitahara T, Yoshida T, Nakajima H, Tani T, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:576–583. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakajima H, Hori Y, Terano H, Okuhara M, Manda T, Matsumoto S, Shimomura K. Antibiot. 1996;49:1204–1211. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Thompson CF, Jamison TF, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10482–10483. [Google Scholar]; (b) Thompson CF, Jamison TF, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9974–9983. doi: 10.1021/ja016615t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Horigome M, Motoyoshi H, Watanabe H, Kitahara T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:8207–8210. [Google Scholar]; (d) Motoyoshi H, Horigome M, Watanabe H, Kitahara T. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:1378–1389. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Albert BJ, Koide K. Org Lett. 2004;6:3655–3658. doi: 10.1021/ol049160w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Albert BJ, Sivaramakrishnan A, Naka T, Koide K. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2792–2793. doi: 10.1021/ja058216u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Albert BJ, Sivaramakrishnan A, Naka T, Czaicki NL, Koide K. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2648–2659. doi: 10.1021/ja067870m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Ghosh AK, Chen ZH. Org Lett. 2013;15:5088–5091. doi: 10.1021/ol4024634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK, Chen ZH, Effenberger KA, Jurica MS. J Org Chem. 2014;79:5697–5709. doi: 10.1021/jo500800k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He H, Ratnayake AS, Janso JE, He M, Yang HY, Loganzo F, Shor B, O’Donnell CJ, Koehn FE. J Nat Prod. 2014;77:1864–1870. doi: 10.1021/np500342m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Pazos G, Pérez M, Gándara Gómez G, Fall Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:5285–5287. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoberg JO. Carbohydr Res. 1997;300:365–367. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mori Y, Hayashi H. J Org Chem. 2001;66:8666–8668. doi: 10.1021/jo0107103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel-Magid AF, Carson KG, Harris BD, Maryanoff CA, Shah RD. J Org Chem. 1996;61:3849–3862. doi: 10.1021/jo960057x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scholl M, Ding S, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. Org Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trnka TM, Morgan JP, Sanford MS, Wilhelm TE, Scholl M, Choi T-L, Ding S, Day MW, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2546–2558. doi: 10.1021/ja021146w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicolaou KC, Rhoades D, Lamani M, Pattanayak MR, Kumar SPM. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:7532–7535. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki A. J Organomet Chem. 1999;576:147–168. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biajoli AFP, Schwalm CS, Limberger J, Claudino TS, Monteiro AL. J Braz Chem Soc. 2014;25:2186–2214. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Optical rotation of natural spliceostatin G has not been reported (see reference18)

- 27.Effenberger KA, Anderson DD, Bray WM, Prichard BE, Ma N, Adams MS, Ghosh AK, Jurica MS. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:1938–1947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.515536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.