Abstract

Personal space regulation is a key component of effective social engagement. Personal space varies among individuals and with some mental health conditions. Simulated personal space intrusions in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) reveal larger preferred interpersonal distance in that setting. These findings led us to conduct the first test of live interpersonal distance preferences in symptoms in BPD. With direct observation of subjects’ personal space behavior in the stop-distance paradigm, we found a 2-fold larger preferred interpersonal distance in BPD than control (n = 30, n = 23). We discuss this result in context of known biology and etiology of BPD. Future work is needed to identify neural circuits underlying personal space regulation in BPD, individual differences in preferred interpersonal distance in relation to specific symptoms and relationship to recovery status.

1. Introduction

1.1 Personal Space

Personal space refers to “the area individuals maintain around themselves into which others cannot intrude without arousing discomfort” and governs each person’s preferred interpersonal distance from others (Hayduk, 1983). Personal space has been theorized to serve a protective function by regulating one’s distance from potential emotional and physical threats while also allowing for an appropriate level of intimacy and trust in social contexts (Lloyd, 2009). Preferred interpersonal distance is one way to describe personal space in a measurement task (e.g. the stop-distance paradigm described in detail below). For each individual, preferred interpersonal distancevaries according to psychological state and situational circumstances, for example, degree of familiarity with one’s interaction partner (Hayduk, 1983), gender roles (Uzzell and Horne, 2006), and emotional valence of the interaction (Tajadura-Jiménez et al., 2011). However, there is also evidence that personal space is a stable trait (Perry et al., 2016), varying between individuals according to such factors as attachment style (Yukawa et al., 2007b) and varying levels of social anxiety in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Perry et al., 2013).

1.2 Personal Space and Borderline Personality Disorder

Personal space regulation is understudied in borderline personality disorder (BPD), a severe personality disorder characterized by problems with mood, impulse control, and interpersonal functioning (Lieb et al., 2004) as well as altered amygdala function (Schulze et al., 2016), disordered attachment (Levy et al., 2015) and impairments in mentalization (see discussion of mentalization below) (Fonagy et al., 2003).

Disturbed social relationships have been considered central to the phenotype of BPD (Gunderson, 2007) and empirical studies of interpersonal functioning in BPD have found widespread alterations in perceptual biases, social cognition, theory of mind, trust and cooperation (for review see (Lazarus et al., 2014)).

Two recent studies of imagined social experiences have suggested that personal space may be altered in BPD. In a study of implicit and explicit behavioral activation, BPD patients and controls were asked how many steps they imagined they would take toward or away from faces shown to them in photographs. BPD patients imagined more steps away from both the happy and fearful faces than controls (Kobeleva et al., 2014). More recently, a neuroimaging study found that simulating personal space intrusion by zooming in on pictures of emotional faces activated fronto-parietal regions and the amygdala in BPD patients and controls (Schienle et al., 2015). BPD patients endorsed a larger preferred interpersonal distance in a pen and paper task. They also had increased activation of both amygdala and fronto-parietal cortex in the fMRI task, but only towards looming disgusted faces (not faces expressing other emotions). It is important to note, however, that neither of these studies involved live interpersonal interactions – only imagined ones.

1.3 Methods for measuring personal space regulation

Personal space regulation is an essential component of social interaction. However, these dynamic aspects of social exchange have been difficult to capture in traditional experimental probes of social cognition. Typically, studies of preferred interpersonal distance have relied on derivate stimuli (e.g. disembodied faces) abstracted from social context (Adolphs, 2006; McCall, 2016). When looking at individuals with BPD, utilizing methods such as drawing circles around figures (e.g. Schienle et al., 2016) is likely less reliable than observing live interaction (Harrigan, 2008; Hayduk, 1983; McCall, 2016). Some researchers have argued that individuals with BPD may struggle to accurately describe their emotions in response to hypothetical situations, particularly when they are emotionally aroused (Bateman, 2004). If this is the case, direct observation of behavior may be essential to accurately measuring differences in preferred interpersonal distance (and other social behaviors) among people with BPD.

1.4 Current study: a live interpersonal paradigm to test personal space preferences in BPD

To overcome the limitations of previous studies in BPD, we employed a more ecologically valid method: the stop-distance paradigm. This is a highly reliable measure of preferred interpersonal distance that is performed in a live 2-person interaction in the lab (Aiello, 1987; Hayduk, 1983; Perry et al., 2016). Study participants are asked to indicate when an approaching confederate has stepped into their personal space.

The study included only female subjects. The approaching strangers (confederates) were also all young women. We selected the single-gender experimental design given expected differences in BPD presentation by gender which we predicted might markedly increase heterogeneity of preferred interpersonal distance. Men with BPD are less likely to present for clinical care, though the condition has been found in some studies to be equally prevalent in men and women in community samples, and men with BPD are more likely to have substance use disorders and to exhibit externalizing behavior (Bayes and Parker, 2017). Proxemic behavior in the stop-distance task has been shown to differ between women and men: female research subjects show a larger difference between distance preferences from men (larger) and women (shorter) than do male subjects (Miller et al., 2013) (Holt et al., 2014).

To our knowledge, this is the first study of personal space regulation in BPD in a live dyadic context, involving face to face interaction with another individual. We used the stop-distance paradigm to test the hypothesis that disrupted interpersonal functioning in BPD manifests in increased preferred interpersonal distance in an encounter with a stranger.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Women aged 18–60 were recruited from the community via posters and online advertisements.. This study was approved by the Yale Institutional Review Board and all subjects gave informed consent. Initial screen was done over the phone; subjects were then screened by a psychiatrist (SKF) using semi-structured interviews (Structured Interview for DSM-IV: controls had no psychiatric conditions, BPD subjects had no current substance dependence and no primary psychotic disorder; Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Personality Disorder (Zanarini et al., 2002): controls scored ≤ 4 (scaled total), BPD subjects scored ≥ 8 (scaled total)). Included subjects also read English well (no history of special education, ≤ 11 errors on the Wide Range Achievement Test 4th Edition (WRAT-4) reading test (Wilkinson, 2006)), had no history of head injury or neurologic condition, and had no gait disturbance.

We collected information on subject education level, hours of work and/or schoolwork per week, current relationship status, and reading level (to detect differences among the more literate subjects in our sample, we used the more challenging North American Adult Reading Test (NAART) instead of the WRAT-4 score here) (Uttl, 2002).

2.2 Self-report scales

Subjects also completed commonly used validated self-report scales. The Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23) is a 23 item scale with established reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.94–0.96) and validity (r = 0.96 versus the longer BSL-95, r = 0.87 versus the Beck Depression Inventory, and r = 0.48 versus the general psychopathology scale SCL-90) in initial psychometric studies (Bohus et al., 2009). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.95. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21 item scale is established reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.94) and validity (r = 0.54 versus diary reports of anxiety) in an initial psychometric validation study (Beck et al., 1988; Fydrich et al., 1992). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.95. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) is a 21 item scale with established reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.9) and validity (r = 0.71 – 0.86 versus a range of commonly used depression scales) in a large meta-analysis (Steer et al., 1999; Wang and Gorenstein, 2013). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.97. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) is a 30 item scale with slightly lower reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.79–0.82) and good discriminant validity (ANOVA comparing healthy to impulsive groups F(3,657) = 27.49, p < 0.0001) (Patton et al., 1995). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.61 (consistent with lower value in established psychometric properties). The Peters Delusion Inventory (PDI) is a 21 item scale to measure delusions and delusion-like experiences (Peters et al., 2004), including PDI subscales for belief intensity, belief-associated distress, and conviction. It has established reliability (Cronbach’s alpha is 0.82) and validity (r = 0.61 versus other delusion scales). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

2.3 Stop distance paradigm

To determine preferred interpersonal distance, subjects began standing face-to-face and 6 feet away from a female confederate. On each of 3 trials, the confederate slowly approached the subject. The confederate was always a young woman, and always stood up straight, made consistent eye contact, and maintained a neutral facial expression. Several different graduate students served as confederate over the course of the study. The subjects were instructed that the confederate would walk towards them until they said stop. They were instructed, “Say stop when you feel uncomfortable.” Final toe to toe distance was measured using a tape measure, and mean preferred interpersonal distance for the three trials was computed.

3. Results

We enrolled 30 women in the control group and 23 women in the BPD group. The two groups were matched on age, years of education, current work status, current relationship status, and reading ability (Table 1). In the control group, 10% were Asian, 26.7% were Black, 10% Hispanic, 36.7% White. In the BPD group, 4.3% were Asian, 13% Black, 4.3% South Asian, 4.3% Latina, 56.5% White. Women in the BPD group were significantly more symptomatic on a dimensional measure of BPD symptoms (BSL) as well as self-report measures of depression (BDI), anxiety (BAI), and impulsivity (BIS) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Subject demographics. Mean results are reported followed by standard deviations.

| control | BPD | statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 30 | 23 | |

| Age (yrs) | 33.4 +/− 13.05 | 36.9 +/− 12.5 | t = 0.10, p = 0.32 |

| Education (yrs) | 15.2 +/− 2.69 | 14.0 +/− 2.52 | t = 1.66, p = 0.1 |

| Reading level (NAART score) | 21.2 +/− 9.04 | 19.77 +/− 7.55 | t = 0.59, p = 0.55 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 10% | 8.60% | Chi-square = 1.31, |

| Black | 26.70% | 13% | df = 8, p = 0.10 |

| Hispanic | 10% | 4.30% | |

| White | 36.70% | 56.50% | |

| Not reported | 5% | 17.40% | |

| Taking psychiatric meds | 0 | 52.20% | |

| Anti-depressant | 0 | 26.10% | |

| Mood stabilizer | 0 | 26.10% | |

| Anti-psychotic | 0 | 13% | |

| Benzodiazepine | 0 | 21.70% | |

| Current relationship | t = −0.64, p = 0.53 | ||

| None | 40% | 34.80% | |

| In a relationship | 36.70% | 47.80% | |

| No answer | 23.30% | 17.40% | |

| Current work or school | |||

| None | 40% | 21.70% | Chi-square = 2.62, |

| 0–20 hours/week | 20% | 34.80% | df = 2, p = 0.26 |

| 20+ hours/week | 20% | 26.10% | |

| No answer | 20% | 17.40% |

Table 2.

Subject symptoms on self-report scales. Mean results of self-report scales are reported followed by standard deviations in parentheses. T-tests reveal significant differences between groups in self-reported Borderline symptoms (BSL), depressive symptoms (BDI), anxiety symptoms (BAI), and impulsivity (BIS).

| Control | BPD | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSL | |||

| n | 26 | 21 | |

| Mean ± SD | 5.08 ± 6.2 | 32.19 ± 19.06 | t = −6.26, p < 0.001 |

| BDI | |||

| n | 27 | 20 | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.56 ± 4.3 | 2.14 ± 13.9 | t = −6.16, p < 0.001 |

| BAI | |||

| n | 27 | 20 | |

| Mean ± SD | 6.52 ± 9.2 | 23.0 ± 12.8 | t = −4.90, p < 0.001 |

| BIS | |||

| n | 25 | 21 | |

| Mean ± SD | 51.10 ± 9.59 | 71.0 ± 16.5 | t = −5.10, p < 0.001 |

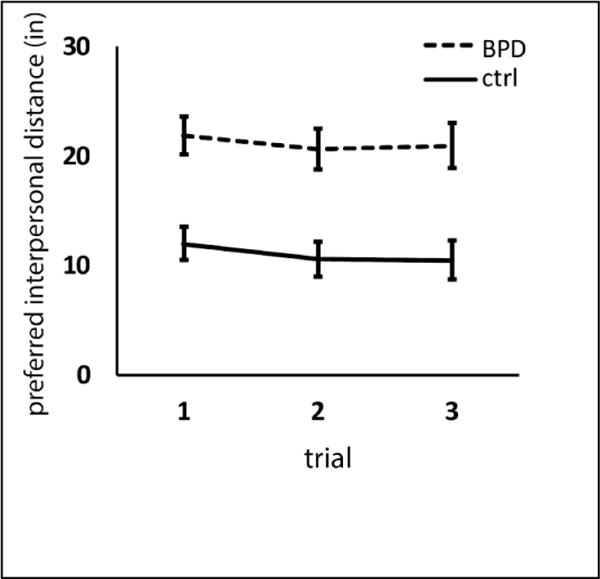

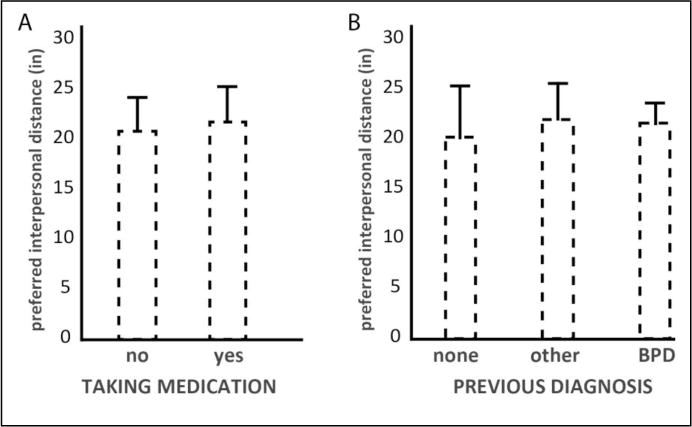

Preferred interpersonal distance was more than two-fold larger in the BPD group versus control (Figure 1). Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant differences by group (F = 16.98, p < 0.001) and by trial (F = 5.21, p = 0.009) but no trial by group interaction (F = 0.196, p = 0.822). Post-hoc tests revealed significant shortening of preferred interpersonal distance from trial 1 to 2 which was maintained at trial 3 (Tukey’s b for trial 1 × 2 p = 0.003, for trial 1 × 3 p = 0.052, for trial 2 × 3 p = 0.730). Figure 2 shows mean interpersonal distance in the sub-groups of people with BPD who were taking medication or not (2A) and who carried a previous mental health diagnosis or not (2B). The data are displayed here to provide a preliminary sense of distribution though the sample is not adequately powered to permit subgroup analyses.

Figure 1.

Preferred interpersonal distance is significantly greater in BPD than control subjects (Repeated measures ANOVA. F = 16.98, p < 0.001). Preferred interpersonal distance decreases from trial 1 to 2, but not again from trial 2 to trial 3 (F = 5.21, p = 0.009, Tukey’s b for trial 1 × 2 p = 0.003, for trial 1 × 3 p = 0.052, for trial 2 × 3 p = 0.730). There was no trial × group interaction (F = 0.196, p = 0.822). Error bars depict standard error of the mean.

Figure 2.

Preferred interpersonal distance in BPD subjects who were (A) taking medication or not and BPD subjects who were (B) previously undiagnosed, diagnosed with another mental illness, or diagnosed with BPD. Error bars depict standard error of the mean.

We also examined preferred interpersonal distance and symptom measures within the BPD group. We did not find any significant correlations between preferred interpersonal distanceand BSL (r = 0.36, p = 0.56), BDI (r = 0.02, p = 0.93), BAI (r = 0.22, p = 0.36), BIS (r = 0.26, p = 0.25) score, or psychotic-like symptoms on DIB cognitive subscale (r = 0.12, p = 0.64) or PDI scores (total score r = 0.003, p = 0.99, PDI distress r = -0.04, p = 0.89, PDI preoccupation r = −0.07, p = 0.78, PDI conviction r = 0.08, p = 0.77). However, this sample was underpowered, and we may have missed differences that are present.

4. Discussion

4.1 Enlarged preferred interpersonal distance in the context of known behavior in BPD

In this study, we found that people with BPD prefer a significantly larger interpersonal distance from a stranger than do non-BPD controls. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis, and fits with a growing literature describing the interpersonal perceptions and behavior of people with BPD, and specifically the intolerance of sustained social closeness (though fluctuating states can include profound idealization of others and avoidance of separation as well). One recent study reports differences in social distance appraisal (judgements about how far people are from objects) as a function of self-reported willingness to take anothers’ perspective (Fini et al., 2017). By describing the enlarged distance that we measured in BPD versus control as “preferred” distance, we may seem to suggest that the difference in BPD is certainly due to preferring a larger space. However, an alternative explanation may be that people with BPD actually judge this interpersonal distance to be smaller than would someone without BPD.

People with BPD are also known to have negative attribution bias (judging stimuli, including social stimuli to be more negatively valenced than they are). For example, when viewing the faces of strangers, people with BPD perceive negative emotion though healthy control subjects describe the face as neutral (reviewed in (Schulze et al., 2016). Also, people with BPD are very sensitive to interpersonal experiences, and can often respond in ways that promote interpersonal conflict. This kind of difficulty has been quantified by observing BPD subject behavior in neuroeconomic games. In a brief economic exchange with a stranger, people with BPD responded with less initial trust and less willingness to coax a defecting partner back to continue a mutually-beneficial exchange (King-Casas et al., 2008). People with BPD are also acutely responsive to unfairness and sensitive to rejection, e.g. (Bungert et al., 2015), and rejection sensitivity can modulate response to social threats (Berenson et al., 2009). Furthermore, exposure to exogenous oxytocin, a hormone released in response to intimate interpersonal situations such as parental caregiving and sexual intimacy, women with BPD were less cooperative (Bartz et al., 2011).

These studies have quantified the phenomenon, but the observation of disrupted interpersonal functioning in BPD is not new. Borderline Personality Organization was initially described as a formulation for a group of people who could not tolerate analyst neutrality, and whose clinical status worsened on the psychoanalytic couch (reviewed in (Kernberg and Michels, 2009)). More recently, BPD symptoms have been found to negatively correlate with security of attachment and positively correlated with fearful avoidance attachment (Brennan & Shaver, 1998). Furthermore, Miano et al. found that rejection sensitivity mediates the relationship between BPD symptoms and attribution of untrustworthiness to novel faces (Miano et al., 2013). Insecure attachment style and high rejection sensitivity may be candidate mechanisms for aberrant proxemic behavior in BPD. We were not able to identify any studies that have directly examined the relationship between rejection sensitivity and personal space regulation, but several studies have linked insecure attachment style with enlargement of preferred interpersonal distance in the stop distance paradigm (Yukawa et al., 2007a) (Kaitz et al., 2004). Further work is needed to define mechanisms of change in proxemic behavior in BPD.

4.2 Personal space regulation in other mental illnesses

Personal space regulation and preferred interpersonal distance (in particular) has been more studied in other mental illnesses. Four groups have reported live stop-distance tests in autism spectrum disorder, and results are inconsistent. Asada et al. reported decreased mean preferred interpersonal distance in 16 men with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), compared to 16 typically developing controls, but, symptom intensity did not significantly correlate to preferred interpersonal distance (Asada et al., 2016). Previous studies in children with ASD reported conflicting results. However: Gessaroli found increased preferred interpersonal distance (Gessaroli et al., 2013), whereas Kennedy et al. and Perry et al. found no group differences. Though in Kennedy et al., parents reported significantly larger numbers of personal space intrusions by their ASD children (Kennedy and Adolphs, 2014) (Perry et al., 2015). Perry et al. did go on to define a potential dimensional symptom measure to explain these conflicting data. Social anxiety, which can vary quite broadly in ASD, correlated with preferred interpersonal distance in their sample (Perry et al., 2015). They also noted that the N1 ERP signal, an attentional marker which they measured during a personal space simulation game, “significantly and strongly correlated” with IPD within the ASD sample (Perry et al., 2015). Our study was underpowered to detect differences in preferred interpersonal distance due to specific symptoms, and we did not specifically test social anxiety or attachment style. This will be an important future direction for this work.

Two groups have reported measurements from the stop distance paradigm in schizophrenia, both finding increased preferred interpersonal distance in schizophrenia versus control (Holt et al., 2015) (Schoretsanitis et al., 2016). One group found that preferred interpersonal distance correlates to negative, but not positive symptoms (Holt et al., 2015). The other reported that a feeling of threatened paranoia correlated with increased preferred interpersonal distance, whereas a different flavor of paranoia with a greater sense of personal power abrogated the sensation of personal space intrusion (like the experience of amygdala-lesioned patient). Those patients with schizophrenia but without paranoia behaved on the stop-distance task similarly to control subjects (Schoretsanitis et al., 2016). Holt et al. found that greater activation of the fronto-parietal personal space monitoring network in schizophrenia than in controls in response to looming faces vs. withdrawing faces (Holt et al., 2015).

We identified only one study reporting stop distance behavior in people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In a group of 83 male war veterans with chronic PTSD compared to 85 healthy men, preferred interpersonal distance was increased in PTSD versus control, but the current symptom score did not correlate to preferred interpersonal distance (Bogovic et al., 2014).

In sum, though results have not been fully consistent across studies, it seems that autism may lead to decreased preference for personal space, and negative symptoms of schizophrenia as well as symptoms of PTSD lead to increased personal space.

4.3 Neurobiology of personal space

Studies using brain imaging and examining the responses of brain-lesioned human subjects have defined the amygdala (Kennedy et al., 2009), as well as the dorsal intraparietal sulcus (DIPS) and the ventral premotor cortex (PMv) (Brozzoli et al., 2011) (Holt et al., 2014) as a key regions for processing and regulating personal space preferences. Holt et al. identified DIPS-PMv functional connectivity as a correlate of real-world social activity (Holt et al., 2014). the amygdala. The amygdala is crucially involved in fear conditioning, but is also important for processing emotional cues, such as angry faces (Kim et al., 2016) and ambiguous faces (Davis et al., 2016), for processing non-verbal emotional data such as olfactory fear cues (Hariri and Whalen, 2011), and for social learning (Davis et al., 2010). The fronto-parietal network is implicated in self-regulation (reviewed in (Kelley et al., 2015)) and attentional processes, especially spatial attention (reviewed in (Scolari et al., 2015)), and some argue, internal (self-focused) attention (reviewed in (Luckmann et al., 2014)). Given that fronto-parietal network dysfunction and amgydala dysregulation are reported in several neuropsychiatric conditions including schizophrenia (Anticevic et al., 2012) (Chang et al., 2014), PTSD (Shin et al., 2006; Weber et al., 2005), and autism (Rudie et al., 2011; Swartz et al., 2013), measures of preferred interpersonal distance may be subtle markers of neurological abnormalities underlying interpersonal impairments.

4.4 Potential neurobiological underpinnings of enlarged preferred interpersonal distance in BPD

Amygdala hyperactivity in BPD (Schulze et al., 2016) may drive the increase in preferred interpersonal distance that we have observed in BPD patients. People with BPD respond to looming pictures of faces with amygdala activation (Schienle et al., 2015). However, in a recent meta-analysis of 19 studies with nearly 300 people in each group (BPD vs control), increased amygdala activity was only observed in in unmedicated, and not in medicated, people with BPD (Schulze et al., 2016). The subjects included in the meta-analysis are similarly aged to our sample, and mostly female, however they are nearly all unmedicated (7/19 studies included unmedicated patients, with 3 studies of all unmedicated patients, 3 with 30–40% unmedicated, and another with 93% unmedicated). Our sample was closer to 50% medicated. To increase homogeneity, the Schulze meta-analysis also excluded studies of interactive social games (a social cooperation investment game, a social rejection game). The included studies delivered negative emotional stimuli such as negative words (3 studies), negative faces (e.g. Reading the Mind in the Eyes Task, 5 studies), negative scenes of people (IAPS, 7 studies), and recalled negative personal experience (4 studies). There were no studies that examined interactive social stimuli (as ours did) included in the meta-analysis. Of note, the Schliene paper examining response to looming faces did observe amygdala activation in both medication and unmedicated patients (64% of the sample was medicated) (Schienle et al., 2015).

Strong conclusions about brain regions likely to be differentially activated in interactive social contexts in BPD are not yet possible given the small literature in this area, but further investigation of amygdala as well as insula and cingulate cortex function in medicated and unmedicated BPD patients, as well as rapidly recovered and unrecovered patients will be critical to understanding the social experience of these patients. This is certainly the case for better understanding of personal space regulation, but also in terms of the regulation of interactive social behavior more generally. The simplicity and ecological validity of the stop-distance paradigm may recommend it as a particularly good assay for further studies in this area.

4.5 Limitations

There are several limitations of this work. Our small sample size limits the power to detect differences between subgroups. Our limited resources for the study prevented us from adding additional conditions, such as confederates who are male, who are more familiar to the subject, who show differing affective states, or who do not make eye contact during approach. We elected to have the confederate make eye contact to increase the likelihood that this would be a strong enough stimulus to tease our differences between groups. Personal attributes which we did not examine here also very likely impact on personal space preferences in general and in specific dyadic pairings. Some of these individual factors may include sexual orientation, ethnic and cultural background, socio-economic background, age, and height. Indeed, others have found differences in proxemics of threat perception, for example between western to east Asian contexts (reviewed and discussed in (Su et al., 2012)).

Real world experience of closeness and alienation may also be of particular interest: do people in current intimate relationships perform this task differently with a stranger? We hope that future studies will be able to include larger samples to examine the interaction of psychological states and these other important personal attributes.

Furthermore, considerations about underlying brain mechanisms are speculative, and based on relationship to existing literature, not based on data collection in this sample. We discuss potential neural underpinnings to help relate our findings to current understanding of BPD, and to provide potential links to an emerging neuroscience of proxemics, but further experiments will be needed to directly test these links.

4.6 Summary

In the mental health field, we lack behavioral assays that provide reliable reports of clinical status, brain function, and prognosis in disorders of social cognition. Future studies should test the stop-distance paradigm as part of an interactive social battery testing state and trait markers of social fear and recovery of healthy social cognition in BPD and mental illness more broadly. Another potential use of preferred interpersonal distance data may be as a measure of treatment efficacy: we predict that preferred interpersonal distance will decrease from a helpful therapist over time, and that distance from a stranger will decrease as well. We anticipate that quantifying interpersonal distance preferences will reinforce this aspect of non-verbal communication, perhaps offering therapist and client language for a felt experience of social malaise.

Highlights.

Effective personal space (PS) regulation is important to social functioning.

Personal space preferences vary with psychological state and environmental factors.

Borderline Personality Disorder is a mental illness that arises from and propogates disturbances in interpersonal relationships.

Early life interpersonal experience is encoded in attachment constructs.

We observed a 2-fold increase in preferred interpersonal distance in BPD – this may be a behavioral marker of attachment avoidance.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kristin Budde, Sasha Deutsch-Link, Erin Feeney, Carol Gianessi, Megan Ichinose, Taylor McGuiness, Margot Reed, and for their help as confederates, and Albert Goclowski for his help with preparing and maintaining our testing station at the Connecticut Mental Health Center.

This work was supported by the Connecticut State Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Sarah K. Fineberg was supported by NIMH Grant no. 5T32MH019961, “Clinical Neuroscience Research Training in Psychiatry” and a NARSAD Young Investigator Award (2014–2016). Philip R. Corlett was funded by an IMHRO/Janssen Rising Star Translational Research Award and CTSA Grant Number UL1TR000142 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adolphs R. How do we know the minds of others? Domain-specificity, simulation, and enactive social cognition. Brain Res. 2006;1079(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello JR. Human spatial behavior. Handbook of environmental psychology. 1987;1(1987):389–504. [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Van Snellenberg JX, Cohen RE, Repovs G, Dowd EC, Barch DM. Amygdala recruitment in schizophrenia in response to aversive emotional material: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(3):608–621. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K, Tojo Y, Osanai H, Saito A, Hasegawa T, Kumagaya S. Reduced personal space in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartz J, Simeon D, Hamilton H, Kim S, Crystal S, Braun A, Vicens V, Hollander E. Oxytocin can hinder trust and cooperation in borderline personality disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2011;6(5):556–563. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AWAW. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. Journal of personality disorders. 2004;18(1):36–51. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.1.36.32772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayes A, Parker G. Borderline personality disorder in men: A literature review and illustrative case vignettes. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenson KR, Gyurak A, Ayduk O, Downey G, Garner MJ, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Rejection sensitivity and disruption of attention by social threat cues. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43(6):1064–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogovic A, Mihanovic M, Jokic-Begic N, Svagelj A. Personal space of male war veterans With posttraumatic stress disorder. Environment and Behavior. 2014;46(8):929–945. [Google Scholar]

- Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, Stieglitz RD, Domsalla M, Chapman AL, Steil R, Philipsen A, Wolf M. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32–39. doi: 10.1159/000173701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozzoli C, Gentile G, Petkova VI, Ehrsson HH. FMRI adaptation reveals a cortical mechanism for the coding of space near the hand. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(24):9023–9031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1172-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungert M, Koppe G, Niedtfeld I, Vollstadt-Klein S, Schmahl C, Lis S, Bohus M. Pain Processing after Social Exclusion and Its Relation to Rejection Sensitivity in Borderline Personality Disorder. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0133693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X, Shen H, Wang L, Liu Z, Xin W, Hu D, Miao D. Altered default mode and fronto-parietal network subsystems in patients with schizophrenia and their unaffected siblings. Brain research. 2014;1562:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FC, Johnstone T, Mazzulla EC, Oler JA, Whalen PJ. Regional response differences across the human amygdaloid complex during social conditioning. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(3):612–621. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FC, Neta M, Kim MJ, Moran JM, Whalen PJ. Interpreting ambiguous social cues in unpredictable contexts. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11(5):775–782. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsw003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fini C, Bardi L, Epifanio A, Committeri G, Moors A, Brass M. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of the inferior frontal cortex affects the “social scaling” of extrapersonal space depending on perspective-taking ability. Exp Brain Res. 2017;235(3):673–679. doi: 10.1007/s00221-016-4817-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fydrich T, Dowdall D, Chambless DL. Reliability and Validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1992;6(1):55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gessaroli E, Santelli E, di Pellegrino G, Frassinetti F. Personal space regulation in childhood autism spectrum disorders. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG. Disturbed relationships as a phenotype for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1637–1640. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Whalen PJ. The amygdala: inside and out. F1000 Biol Rep. 2011;3:2. doi: 10.3410/B3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan JA. Proxemics, Kinesics, and Gaze. In: Harrigan J, Rosenthal R, Scherer K, editors. The new handbook of methods in nonverbal behavior research. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. pp. 137–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hayduk LA. Personal space: Where we now stand. Psychol Bull. 1983;94(2):293–335. [Google Scholar]

- Holt DJ, Boeke EA, Coombs G, DeCross SN, Cassidy BS, Stufflebeam S, Rauch SL, Tootell RBH. Abnormalities in personal space and parietal–frontal function in schizophrenia. NeuroImage : Clinical. 2015;9:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DJ, Cassidy BS, Yue X, Rauch SL, Boeke EA, Nasr S, Tootell RB, Coombs G., 3rd Neural correlates of personal space intrusion. J Neurosci. 2014;34(12):4123–4134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0686-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaitz M, Bar-Haim Y, Lehrer M, Grossman E. Adult attachment style and interpersonal distance. Attach Hum Dev. 2004;6(3):285–304. doi: 10.1080/14616730412331281520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley WM, Wagner DD, Heatherton TF. In search of a human self-regulation system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:389–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Adolphs R. Violations of personal space by individuals with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Glascher J, Tyszka JM, Adolphs R. Personal space regulation by the human amygdala. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(10):1226–1227. doi: 10.1038/nn.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg OF, Michels R. Borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(5):505–508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Solomon KM, Neta M, Davis FC, Oler JA, Mazzulla EC, Whalen PJ. A face versus non-face context influences amygdala responses to masked fearful eye whites. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11(12):1933–1941. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsw110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King-Casas B, Sharp C, Lomax-Bream L, Lohrenz T, Fonagy P, Montague PR. The rupture and repair of cooperation in borderline personality disorder. Science. 2008;321(5890):806–810. doi: 10.1126/science.1156902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobeleva X, Seidel EM, Kohler C, Schneider F, Habel U, Derntl B. Dissociation of explicit and implicit measures of the behavioral inhibition and activation system in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2014;218(1–2):134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus SA, Cheavens JS, Festa F, Zachary Rosenthal M. Interpersonal functioning in borderline personality disorder: A systematic review of behavioral and laboratory-based assessments. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(3):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy KN, Scala JW, Temes CM, Clouthier TL. An integrative attachment theory framework of personality disorders. In: Huprich SK, Huprich SK, editors. Personality disorders: Toward theoretical and empirical integration in diagnosis and assessment. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, US: 2015. pp. 315–343. [Google Scholar]

- Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet. 2004;364(9432):453–461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd DM. The space between us: A neurophilosophical framework for the investigation of human interpersonal space. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33(3):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckmann HC, Jacobs HI, Sack AT. The cross-functional role of frontoparietal regions in cognition: internal attention as the overarching mechanism. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;116:66–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall C. Mapping Social Interactions: The Science of Proxemics. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2016 doi: 10.1007/7854_2015_431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miano A, Fertuck EA, Arntz A, Stanley B. Rejection sensitivity is a mediator between borderline personality disorder features and facial trust appraisal. J Pers Disord. 2013;27(4):442–456. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2013_27_096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller HC, Chabriac AS, Molet M. The impact of facial emotional expressions and sex on interpersonal distancing as evaluated in a computerized stop-distance task. Can J Exp Psychol. 2013;67(3):188–194. doi: 10.1037/a0030663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Levy-Gigi E, Richter-Levin G, Shamay-Tsoory SG. Interpersonal distance and social anxiety in autistic spectrum disorders: A behavioral and ERP study. Soc Neurosci. 2015;10(4):354–365. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2015.1010740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Nichiporuk N, Knight RT. Where does one stand: a biological account of preferred interpersonal distance. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11(2):317–326. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Rubinsten O, Peled L, Shamay-Tsoory SG. Don’t stand so close to me: A behavioral and ERP study of preferred interpersonal distance. Neuroimage. 2013;83:761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E, Joseph S, Day S, Garety P. Measuring delusional ideation: the 21-item Peters et al. Delusions Inventory (PDI) Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(4):1005–1022. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudie JD, Shehzad Z, Hernandez LM, Colich NL, Bookheimer SY, Iacoboni M, Dapretto M. Reduced functional integration and segregation of distributed neural systems underlying social and emotional information processing in autism spectrum disorders. Cereb Cortex. 2011 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A, Wabnegger A, Schongassner F, Leutgeb V. Effects of personal space intrusion in affective contexts: an fMRI investigation with women suffering from borderline personality disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2015;10(10):1424–1428. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoretsanitis G, Kutynia A, Stegmayer K, Strik W, Walther S. Keep at bay! – Abnormal personal space regulation as marker of paranoia in schizophrenia. European Psychiatry. 2016;31:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze L, Schmahl C, Niedtfeld I. Neural correlates of disturbed emotion processing in borderline personality disorder: a multimodal meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(2):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolari M, Seidl-Rathkopf KN, Kastner S. Functions of the human frontoparietal attention network: Evidence from neuroimaging. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2015;1:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin LM, Rauch SL, Pitman RK. Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1071:67–79. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF, Beck AT. Dimensions of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in clinically depressed outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55(1):117–128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199901)55:1<117::aid-jclp12>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Zheng Y, Li S. Culture, distance, and threat perception: comment on Stamps (2011) Percept Mot Skills. 2012;115(3):752–754. doi: 10.2466/27.07.21.PMS.115.6.752-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Wiggins JL, Carrasco M, Lord C, Monk CS. Amygdala habituation and prefrontal functional connectivity in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(1):84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajadura-Jiménez A, Pantelidou G, Rebacz P, Västfjäll D, Tsakiris M. I-Space: the effects of emotional valence and source of music on interpersonal distance. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttl B. North American Adult Reading Test: age norms, reliability, and validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24(8):1123–1137. doi: 10.1076/jcen.24.8.1123.8375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzzell D, Horne N. The influence of biological sex, sexuality and gender role on interpersonal distance. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2006;45(3):579–597. doi: 10.1348/014466605X58384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YP, Gorenstein C. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: a comprehensive review. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35(4):416–431. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DL, Clark CR, McFarlane AC, Moores KA, Morris P, Egan GF. Abnormal frontal and parietal activity during working memory updating in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2005;140(1):27–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test 4. Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, FL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yukawa S, Tokuda H, Sato J. Attachment style, self-concealment, and interpersonal distance among Japanese undergraduates. Percept Mot Skills. 2007a;104(3 Pt 2):1255–1261. doi: 10.2466/pms.104.4.1255-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukawa S, Tokuda H, Sato J. Attachment style, self-concealment, and interpersonal distance among Japanese undergraduates. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2007b;104(3 suppl):1255–1261. doi: 10.2466/pms.104.4.1255-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines. J Pers Disord. 2002;16(3):270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]