Abstract

Objective

To describe health service patterns before opioid-related death among non-elderly individuals in the Medicaid program focusing on decedents with and without past year diagnoses of non-cancer chronic pain.

Methods

We identified opioid-related decedents, ages 12 to 64 years in the Medicaid program, and characterized their clinical diagnoses, filled medication prescriptions, and non-fatal poisoning events during the 30 days and 12 months before death. The study group included 13,089 opioid-related deaths partitioned by presence or absence of chronic non-cancer pain diagnoses in the last year of life.

Results

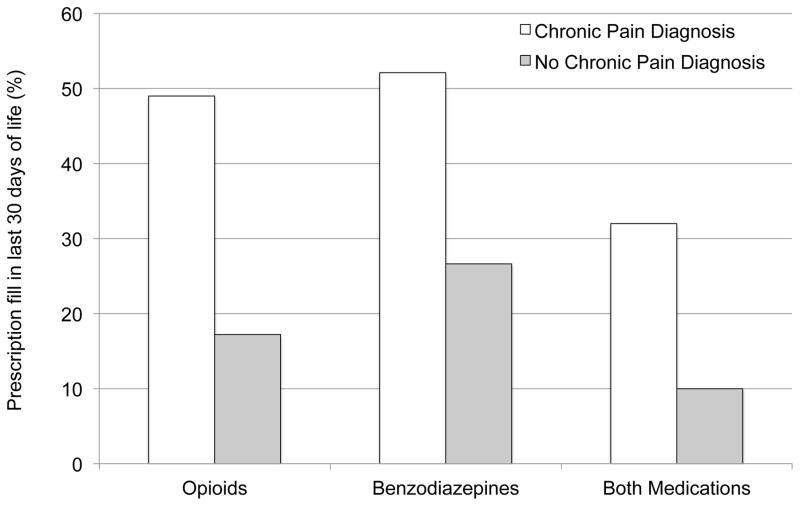

Most decedents (61.5%) had received clinical diagnoses of chronic non-cancer pain conditions in the last year of life. As compared to fatalities without chronic pain diagnoses, those with these diagnoses were significantly more likely to have filled prescriptions for opioids (49.0% vs. 17.2%, p<.0001) and benzodiazepines (52.1% vs. 26.6%, p<.0001) during the last 30 days of life, while diagnoses of opioid use disorder during this period were uncommon in both groups (4.2% vs. 4.3%, p=0.87). The chronic pain group was also significantly more likely than the non-pain group to receive clinical diagnoses of drug use (40.8% vs. 22.1%, p<.0001), depression (29.6% vs. 13.0%, p<.0001) or anxiety (25.8% vs. 8.4%, p<.0001) disorders during the last year of life.

Conclusions

Persons dying of opioid-related causes, particularly those who were diagnosed with chronic pain conditions, commonly received services related to drug use disorders and mental disorders in the last year of life, though opioid use disorder diagnoses near the time of death were rare.

The United States is confronting an unprecedented epidemic of opioid overdose deaths. In 2015, unintentional overdoses claimed 52,404 US lives and nearly two-thirds (63.1%) of these deaths involved opioids (1). Between 2000 and 2014, the annual rate of overdose deaths involving opioids tripled from 3.0 to 9.0 per 100,000 persons (2). In addition to overdose deaths, there were more than 360,000 emergency department visits in 2011 related to nonmedical use of prescription opioids which is more than double the number in 2005 (3). In response to the increase in opioid-related morbidity and mortality, federal, state, and local governments are implementing a range of policies and programs aimed at reducing inappropriate prescribing of opioid analgesics (4–6) and increasing access to treatments for opioid dependence (7–9).

Much remains to be learned about the characteristics of people who die of opioid-related overdose. Characterizing common health care use patterns during the months preceding these fatalities might yield insights into clinical opportunities to identify high risk patients. Although many fatalities are related to use of illicitly obtained drugs, a statewide study of 298 unintentional overdose fatalities in West Virginia reported that 29.1% filled prescriptions for analgesics and 64.8% filled prescriptions for alprazolam in the 30 days before death (10). A study from North Carolina reported that among 301 unintentional opioid analgesic deaths, treatment of musculoskeletal disorders (43.2%) was more common in the year preceding death than treatment of drug dependence (15.6%) (11).

Because the national increase in opioid-related deaths has coincided with escalating use of prescription opioids, concern has focused on the contribution that therapeutic opioids to treat chronic pain may make to opioid-related mortality (12–14). In a case control study, opioid-related decedents were three times as likely as the comparison group to have had a chronic pain condition (15). These findings raise the possibility that people with chronic pain who die of opioid-related conditions may be a distinct subgroup of opioid-related deaths, though no previous research has examined this issue.

A greater understanding of the health services used by individuals prior to opioid-related death may inform efforts to improve clinical identification of risk. In the following analysis, we describe health service use patterns preceding opioid-related deaths stratified by past year clinical diagnosis of a non-cancer chronic pain condition. We focused on service use during the 12 months and 30 days prior to opioid-related death. The analysis was limited to Medicaid enrollees, a population at high risk of opioid overdose death (16).

Methods

Sources of Data

Opioid-related deaths were extracted from 2001–2007 national (45 states, not including AZ, DE, NV, OR, RI) Medicaid Analytic Extract (MAX) data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Dates and cause of death information in the study decedents were derived from linkage to the National Death Index (NDI), which provides a complete accounting of state-recorded deaths in the US, and is the most complete resource for tracing mortality in national samples (17). The NDI segment variables were linked to the Medicaid administrative data by the National Center for Health Statistics. The project was reviewed and approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board.

Study Samples and Follow-Back

Because in adults ages ≥65 years Medicare covered services renders Medicaid claims records incomplete, we restricted the sample to individuals who were ≤64 years of age at the time of opioid overdose death. Following the CDC definition of drug overdose deaths involving opioids, deaths included poisonings by and adverse effects of opioids (T40.0X), heroin (T40.1X), other natural and semi-synthetic opioids (T40.2X), methadone (T40.3X), synthetic opioids other than methadone (T40.4X), and unspecified narcotics (T40.6X) (1). In order to assess service use during the 12-months preceding death, we further restricted the sample to decedents who were continuously enrolled in the Medicaid program for at least 12 months prior to death.

Opioid-related deaths were partitioned by occurrence of at least 1 inpatient or at least 2 outpatient claims with a chronic non-cancer pain diagnosis in the last year of life (18) (Table S1). To increase the generalizability of the results, patients with cancer diagnoses were included in the study sample. However, neoplasm related pain (ICD-9-CM: 338.3) was not included in the definition of the chronic non-cancer pain variable.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Based on Medicaid eligibility data, decedents were classified by sex, age in years (<24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64), and race/ethnicity: Hispanic; white, non-Hispanic (white); black, non-Hispanic (black); and other, non-Hispanic (other) including American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

Service claims classified decedents by any outpatient visits and any visits with substance use, drug use, opioid use, and alcohol use disorder diagnoses during the 30 days and 12 months before death (Table S1). Because acute services separated by fewer than 2 days may represent single care episodes (19), service dates for in-hospital deaths were initiated 2 days before the index inpatient admission.

Pharmacy claims classified decedents with respect to presence of filled prescriptions for opioids, benzodiazepines, their combination, antidepressants, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers during the 30 days and 12 months before death. Decedents were also classified with respect to selected overdose (nonfatal poisoning) events during these time periods including opioid, anxiolytic/sedative, other psychotropic medication, and alcohol overdoses (Table S1).

Variables representing diagnosis of selected specific mental disorders on or within 365 days before the date of death were defined drug use, opioid use, alcohol use, depression, anxiety, bipolar, schizophrenia, personality, and other mental disorders. At least 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient diagnoses defined clinical diagnosis of each mental disorder group. Decedents were also characterized with respect to selected causes of death (Table S1).

Analysis

We compared the percentages of decedents in the two chronic pain diagnosis groups by the demographic, service use, prescription, and cause of death variables. In view of the large sample sizes and number of comparisons, two tailed alpha was set at 0.001.

Results

Demographic and service use characteristics

Among the 13,089 opioid-related decedents, 61.5% were diagnosed with a chronic pain condition during the year prior to death. This included 59.3% who were diagnosed with back pain, 24.5% with headaches, and 6.9% with neuropathies; virtually all of the decedents in the chronic pain group were also diagnosed with other bodily pain conditions (99.6%) (Data not shown).

Most of the decedents were between 35 and 54 years of age and non-Hispanic white in race/ethnicity. Over half (57.6%) received ≥1 outpatient visits in the 30 days prior to death. Although receiving a diagnosis of substance use disorders was common in the 12 months prior to death (42.2%), relatively few were diagnosed with substance use disorders (12.3%) in the last 30 days of life and even fewer (4.2%) were diagnosed with opioid use disorder (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and service use in 30 days and 12 months before opioid-related death by clinical diagnosis of chronic pain conditionsA

| Demographic Characteristics | Total opioid-related deaths % (N=13,089) | Opioid-related deaths with chronic pain diagnoses % (N=8,050) | Opioid-related deaths without chronic pain diagnoses % (N=5,039) | Statistics (×2) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 115.6 | <.0001 | |||

| < 24 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 6.9 | ||

| 25–34 | 13.2 | 12.8 | 13.4 | ||

| 35–44 | 33.1 | 34.3 | 31.2 | ||

| 45–54 | 38.4 | 39.1 | 37.4 | ||

| 55–64 | 10.7 | 10.6 | 10.7 | ||

| Sex | 141.5 | <.0001 | |||

| Male | 51.2 | 47.1 | 57.8 | ||

| Female | 48.8 | 52.9 | 42.3 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 89.7 | <.0001 | |||

| Hispanic | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.9 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 83.3 | 85.6 | 79.7 | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10.7 | 8.9 | 13.5 | ||

| Other, non-Hispanic | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 | ||

| Service use | |||||

| Any outpatient visits | |||||

| 30 days | 57.6 | 71.8 | 34.9 | 1737.5 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 87.3 | 98.6 | 69.3 | 2412.6 | <.0001 |

| Any substance use diagnosis | |||||

| 30 days | 12.3 | 14.0 | 9.6 | 55.8 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 42.2 | 50.9 | 28.3 | 648.7 | <.0001 |

| Any drug use diagnosis | |||||

| 30 days | 10.2 | 11.4 | 8.1 | 39.2 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 37.2 | 45.4 | 24.2 | 596.7 | <.0001 |

| Any opioid use diagnosis | |||||

| 30 days | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 0.03 | .87 |

| 12 months | 14.8 | 16.2 | 12.7 | 28.7 | <.0001 |

| Any alcohol use diagnosis | <.0001 | ||||

| 30 days | 3.3 | 4.0 | 2.2 | 30.2 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 15.1 | 17.8 | 10.6 | 126.0 | <.0001 |

Data from MAX files.

Chronic pain conditions defined by diagnoses in year prior to death.

As compared to fatalities without a past year history of chronic pain diagnoses, fatalities with chronic pain claims histories were more likely to be female and white. They were also more likely to have received any outpatient visit and to have received diagnoses of substance use, drug use, opioid use, and alcohol use disorders during the 30 days and 12 months prior to death (Table 1).

Prescription Medications

Roughly two-thirds of the persons with fatalities filled opioid (66.1%) and benzodiazepine (61.6%) prescriptions during the last 12 months and approximately half (50.2%) filled both (Table 2). Prescriptions for antidepressants (59.0%), antipsychotics (31.6%), and mood stabilizers (35.4%) were also commonly filled during this period. In the last 30 days of life, over one-third (36.8%) of the decedents filled ≥1 opioid prescription. In relation to the decedents without clinical chronic pain diagnoses, those with chronic pain diagnoses were significantly more likely to fill prescriptions for opioids, benzodiazepines, and both opioids and benzodiazepines (Figure 1) as well as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers during both time periods (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prescription of selected medication classes and poisoning events within 30 days and 12 months of opioid-related death by clinical diagnosis of chronic pain conditions

| Prescription Medications | Total opioid-related deaths % (N=13,089) | Opioid-related deaths with chronic pain diagnosesA % (N=8,050) | Opioid-related deaths without chronic pain diagnoses % (N=5,039) | Statistics (×2) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids | |||||

| 30 days | 36.8 | 49.0 | 17.2 | 1348.1 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 66.1 | 81.5 | 41.6 | 2207.8 | <.0001 |

| Benzodiazepines | |||||

| 30 days | 42.3 | 52.1 | 26.6 | 825.1 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 61.6 | 74.0 | 41.9 | 1343.4 | <.0001 |

| Opioids and benzodiazepines | |||||

| 30 days | 23.5 | 32.0 | 10.0 | 834.4 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 50.2 | 64.2 | 27.7 | 1655.6 | <.0001 |

| Antidepressants | |||||

| 30 days | 31.2 | 38.8 | 19.1 | 564.2 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 59.0 | 70.3 | 41.1 | 1091.7 | <.0001 |

| Antipsychotics | |||||

| 30 days | 15.7 | 18.5 | 11.2 | 124.3 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 31.6 | 36.5 | 23.9 | 225.7 | <.0001 |

| Mood stabilizers | |||||

| 30 days | 17.2 | 21.8 | 9.8 | 316.3 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 35.4 | 43.6 | 22.2 | 622.0 | <.0001 |

| Poisoning events | |||||

| Opioid poisoning | |||||

| 30 days | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 15.5 | <.0001 |

| 12 months | 6.2 | 8.1 | 3.1 | 135.0 | <.0001 |

| Benzodiazepine poisoning | |||||

| 30 days | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 13.7 | .0002 |

| 12 months | 3.7 | 5.3 | 1.2 | 139.0 | <.0001 |

| Other psychotropic medication poisoning | |||||

| 30 days | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 8.8 | .003 |

| 12 months | 2.2 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 60.1 | <.0001 |

Data from MAX files.

Chronic pain conditions defined by treatment in year prior to death.

Figure 1. Prescription of opioids, benzodiazepines, and both medication classes within 30 days of opioid-related death by clinical diagnosis of chronic pain conditions.

Results are based data on Medicaid administrative data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and National Death Index data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Nonfatal poisoning

During the 30 days before opioid-related death, 1.0% of the fatalities had a medically treated opioid poisoning (overdose). Decedents with clinical chronic pain diagnoses were approximately twice as likely as those without such clinical diagnoses to have had an opioid overdose. During the 12 months prior to death, 8.1% of decedents with chronic pain diagnoses and 3.1% of those without chronic pain diagnoses had an opioid overdose. Although overdoses related to benzodiazepines and other psychotropic medications were less common, they followed a similar pattern (Table 2).

Mental health diagnoses

Approximately one-third (33.6%) of decedents were diagnosed with drug use disorders in the last year of life. Over this period, a similar percentage received opioid use disorder diagnoses (13.6%) and alcohol use (13.3%) disorder diagnoses. The most commonly diagnosed non-substance use mental disorder was depression followed by anxiety, bipolar, schizophrenia, personality, and other mental disorders (Table 3). In relation to fatalities without past year chronic pain diagnoses, those with these diagnoses were significantly more likely to also have received clinical diagnoses for each substance use and non-substance use mental disorder.

Table 3.

Clinical mental health diagnoses in the 12 months before opioid-related death by clinical diagnosis of chronic pain conditions

| Mental Health DiagnosesA | Total opioid-related deaths % (N=13,089) | Opioid-related deaths with chronic pain diagnosesB % (N=8,050) | Opioid-related deaths without chronic pain diagnoses % (N=5,039) | Statistics (×2) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug use disorder | 33.6 | 40.8 | 22.1 | 489.0 | <.0001 |

| Opioid use disorder | 13.6 | 14.7 | 11.8 | 22.8 | <.0001 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 13.3 | 15.9 | 9.1 | 124.5 | <.0001 |

| Depression disorder | 23.2 | 29.6 | 13.0 | 477.6 | <.0001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 19.1 | 25.8 | 8.4 | 612.9 | <.0001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 12.2 | 15.1 | 7.6 | 162.2 | <.0001 |

| Schizophrenia | 7.8 | 8.7 | 6.4 | 22.3 | <.0001 |

| Personality disorder | 4.2 | 5.8 | 1.8 | 123.0 | <.0001 |

| Other mental disorder | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.9 | .09 |

| No mental disorder | 38.2 | 26.5 | 56.8 | 1205.0 | <.0001 |

Data from MAX files.

Requires at least two outpatient or one inpatient diagnosis in last year

Chronic pain conditions defined by treatment in year prior to death.

Causes of death

Among the opioid-related deaths, poisonings by natural and semisynthetic opioids were the most common followed by methadone, “other narcotics,” synthetic opioids other than methadone, and heroin (Table 4). Benzodiazepine (17.6%) and cocaine (15.5%) poisonings were listed in roughly one in six opioid-related deaths and alcohol was listed in 6.6%.

Table 4.

Selected causes of death among opioid-related deaths by clinical diagnosis of chronic pain conditions

| Poisoning Causes of Death | Total opioid-related deaths % (N=13,089) | Opioid-related deaths with chronic pain diagnosesA % (N=8,050) | Opioid-related deaths without chronic pain diagnoses % (N=5,039) | Statistics (×2) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids subgroups | |||||

| Heroin | 6.5 | 4.9 | 9.9 | 156.0 | <.0001 |

| Methadone | 29.2 | 29.9 | 28.1 | 4.8 | .03 |

| Other synthetic opioids | 15.0 | 16.7 | 12.2 | 49.2 | <.0001 |

| Natural and semisynthetic opioids | 43.0 | 45.6 | 39.0 | 54.0 | <.0001 |

| Other narcotics | 19.0 | 16.5 | 23.1 | 87.2 | <.0001 |

| Cocaine | 15.5 | 12.9 | 19.7 | 111.0 | <.0001 |

| Benzodiazepines | 17.6 | 18.6 | 16.2 | 13.2 | .0003 |

| Alcohol | 6.6 | 5.8 | 7.9 | 23.0 | <.0001 |

Data from MAX files. Opioid subgroups are not mutually exclusive (non-hierarchical).

Chronic pain conditions defined by treatment in year prior to death.

Poisonings with cocaine, heroin, alcohol, and other narcotics were significantly more common causes of death among decedents without than with diagnosed chronic pain conditions. The reverse was true of poisonings with natural and semisynthetic opioids, synthetic opioids other than methadone, and benzodiazepines (Table 4).

Discussion

Most persons with opioid-related fatalities were diagnosed with one or more chronic pain condition in the last year of life. As compared to people with opioid-related deaths without diagnosed chronic pain conditions, the decedents with chronic pain diagnoses were more likely to have also received substance use and other mental health disorder diagnoses. They were also more likely to have filled prescriptions for opioids, benzodiazepines, and other psychotropic medications and to have had a nonfatal drug overdose. The extent of health service use of this population prior to death, including clinical recognition of substance use and other mental disorders, may provide opportunities for detection of overdose risk and early intervention.

The prevalence of opioid prescriptions prior to fatal overdose greatly exceeded the corresponding prescription prevalence in the general population. In the past 30 days, approximately 8.8% of Americans fill prescriptions for analgesics (20). By contrast, 36.8% of the opioid-related decedents filled opioid prescriptions in the last 30 days of their lives. In prior research, a roughly similar proportion (29.1%) of unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities had received opioid prescriptions within 30 days of death (10). Nearly half (49.0%) of decedents with clinically treated chronic pain received opioid prescriptions in the 30 days preceding death. This pattern raises the possibility that health care professionals may frequently be proximal sources of opioids in fatal overdoses. In evaluating these percentages, however, it is important to bear in mind that only a small proportion of Americans with even severe pain meet diagnostic criteria for opioid use disorders (0.75%) (21), suggesting that most individuals with pain are at low risk for opioid overdose.

Benzodiazepines were also commonly prescribed to individuals prior to fatal opioid overdose. Among opioid-related deaths, 42.3% filled benzodiazepine prescriptions in the last month as compared to 4.6% of Americans who report taking anxiolytics, sedatives, or hypnotics in the past 30 days (20). Decedents who had been diagnosed with chronic pain also frequently filled prescriptions for both benzodiazepines and opioids in the last month of life (23.5%). The safety threat posed by benzodiazepine and opioid prescription combinations arises from the potential for benzodiazepines to potentiate opioid induced respiratory depression (22). Most deaths involving opioids result from respiratory depression (23). In roughly one in six opioid-related fatalities, benzodiazepine overdose contributed to the cause of death.

The public health risks of opioid and benzodiazepine co-prescription are highlighted by recent increases in prevalence of such co-prescription (24) and a disproportionate increase in overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines with opioids (25). Coordination of care across providers, routine use of prescription drug monitoring programs, and integration of these programs with electronic medical records might help reduce unintentional co-prescription of benzodiazepines and opioids. Physicians might also reduce these safety risks by restricting benzodiazepine and opioid co-prescribing to patients for whom alternative strategies have proven inadequate, closely monitoring for sedation and respiratory depression, and limiting such co-prescription to minimum clinically required dosage and duration (26).

Approximately one in twenty (6.2%) opioid-related decedents had received medical care for a nonfatal opioid overdose in the last year of life. In a review of medical examiner records from West Virginia (n=295), approximately one in six (16.8%) pharmaceutical overdose fatalities had a lifetime history of nonfatal drug overdose (10). To help place these percentages in context, the annual rate for medically treated opioid overdoses in the general population (California and Florida) was 50.5 per 100,000 population in 2010–11, a 300-fold difference (27). The high relative proportion of opioid-related deaths that are preceded by nonfatal overdoses suggests that nonfatal opioid overdose is a strong risk factor for opioid-related death. This association supports assertive emergency department efforts to engage individuals in treatment for substance use disorders following nonfatal overdose. Yet because a great majority of fatal opioid overdoses are not preceded by medically-treated nonfatal overdoses, public health initiatives to reduce opioid-related deaths must extend beyond improving follow-up treatment for substance use disorder after nonfatal overdoses.

Many of the opioid-related decedents, especially those who had been diagnosed with chronic pain conditions, were also diagnosed with depression, anxiety, or other mental disorders in the last year of life. The high frequency with which clinical attention was devoted to mental disorders prior to opioid-related death, which was also reflected in the psychotropic medication prescribing patterns, suggests that these patients frequently presented complex clinical management challenges. Similar mental health service patterns have been reported in a Utah study in which friends and family reported on opioid-related overdose deaths (28). Psychiatric disorders are common among individuals with chronic pain and opioid use disorders. In one analysis, nearly half of adults with co-occurring chronic pain and opioid use disorder met diagnostic criteria for a current anxiety (48%) or mood (48%) disorders (29). Among adults receiving opioids for chronic pain, major depressive disorder and psychotropic medication prescriptions are associated with an increased risk of prescription opioid dependence (30). In the clinical management of chronic pain, a careful mental health history and periodic structured assessments may help detect opioid-related risks.

In the course of one year, less than one quarter of adults with prescription opioid use disorders receive any substance use treatment (31). By comparison, a larger proportion of opioid fatalities (42.2%) were diagnosed with substance use disorders in the last year of life. However, only a small proportion of these diagnoses were opioid use disorder and most decedents who received substance use disorder diagnoses during the last year did not appear to receive any substance use related services during the last 30 days. Drop out from treatment of substance use disorder may be common in the months preceding opioid-related deaths. Interventions that increase engagement and retention in treatment for substance use disorders could decrease the death toll of opioid overdoses.

This study has several potential limitations. First, there is a potential for misclassification of opioid-related overdoses, though our ICD-10 classification scheme is consistent with consensus recommendations from the Injury Surveillance Workgroup (32) and the CDC (1). Second, different results might have been obtained if privately insured and uninsured opioid-related fatal overdoses were included in the analysis, though Medicaid enrollees are a high risk population (16). Third, our study is based on data from 2001–2007. Since then opioid use, naloxone reversal, and service use patterns have changed in ways that may affect the reported service utilization patterns. For example, there has been a recent marked increase in fentanyl-related overdose deaths that has coincided with an increase in the supply of illicitly manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogs (33). This and other recent trends in fatal opioid-related overdoses are not captured in the present study. Finally, we have no means of capturing opioids that were acquired from illicit sources or of measuring whether patients took medications, including opioids, as prescribed.

In the year prior to death, most individuals with opioid-related fatalities were diagnosed with chronic pain conditions and many were diagnosed with psychiatric disorders and prescribed psychotropic medications. Although the claims histories suggest that clinical attention to substance use disorders was fairly common in the last year of life, few were diagnosed with opioid use disorder the last 30 days of life. These service patterns highlight the need to improve the integration of specialized substance use services in pain treatment clinics and mental health centers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by U19 HS021112 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by R01 DA019606 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr. Huang had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation or approval of the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The views and opinions expressed in this submission are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the US government.

References

- 1.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths – United Sates, 2000–2014. MMWR. 2016;64:1378–1382. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crane EH. The CBHSQ Report: Emergency Department Visits Involving Narcotic Pain Relievers. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(RR-1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. ASTHO prescription drug misuse and abuse strategic map: 2013–2015. ( http://www.astho.org/Rx/Strategic-Map-2013-2015)

- 6.Johnson H, Paulozzi L, Porucznik C, Mack K, Herter B. Decline in drug overdose deaths after state policy changes: Florida, 2010–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:569–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franklin G, Sabel J, Jones CM, et al. A comprehensive approach to address the prescription opioid epidemic in Washington State: milestones and lessons learned. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:463–69. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nosyk B, Anglin MD, Brissette S, et al. A call for evidence-based medical treatment of opioid dependence in the United States and Canada. Health Aff. 2013;32(8):1462–1469. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Pub Health. 2015;105(8):e55–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall AH, Logan JE, Kaplan JA, Kraner JC, Bixler D, Crisy AE, Paulozzi LJ. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2613–2620. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitmire J, Adams G. Unintentional Overdose Deaths in the North Carolina Medicaid Population: Prevalence, Prescription Drug Use, and Medical Care Services. Raleigh, NC: State Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Manocchio T, White JO, Mack KA. Trends in methadone distribution for pain treatment, methadone diversion, and overdose deaths: United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:667–71. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webster LR, Cochella S, Dasgupta N, et al. An analysis of the root causes for opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States. Pain Med. 2011;12(suppl 2):S26–S35. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(9):618–627. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanier WA, Johnson EM, Rolfs RT, Friedrichs MD, et al. Risk factors for prescription opioid-related death, Utah 2008–2009. Pain Medicine. 2012;13(12):1580–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:85–92. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wojcik NC, Huebner WW, Jorgensen G. Strategies for using the National Death Index and the Social Security Administration for death ascertainment in large occupational cohort mortality studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(4):469–477. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohnert AS, Logan JE, Ganoczy D, Dowell D. A detailed exploration into the association of prescribed opioid dosage and overdose deaths among patients with chronic pain. Med Care. 2016;54:435–441. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larochelle MR, Liebschutz JM, Zhang F, Ross-Degnam D, Wharam JF. Opioid prescribing after nonfatal overdose and association with repeated overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:1–9. doi: 10.7326/M15-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville, Maryland: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novak SP, Herman-Stahl M, Flannery B, Zimmerman M. Physical pain, common psychiatric and substance use disorders, and the non-medical use of prescription analgesics in the United States. Drug Alc Depend. 2009;100:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horsfall JT, Sprague JE. The pharmacology and toxicology of the “holy trinity”. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;130:115–119. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corkery JM, Schifano F, Ghodse AH, Oyefeso A. The effects of methadone and its role in fatalities. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2004;19:565–576. doi: 10.1002/hup.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang CS, Kang EM, Kornegav CJ, Jones CM, McAninch JK. Trends in the concomitant prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines, 2002–2014. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NIDA Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

- 26.United States Food and Drug Administration, Drug Safety Communication. FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM518672.pdf.

- 27.Hasegawa K, Brown DF, Tsugawa Y, Camargo CA., Jr Epidemiology of emergency department visits for opioid overdose: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:462–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson EM, Lanier WA, Merrill RM, Crook J, et al. Unintentional prescription opioid-related overdose deaths: description of decedents by next of kin or best contact, Utah, 2008–2009. J Gen Int Med. 2012;28(4):522–529. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barry DT, Cutter CJ, Beitel M, Kerns RD, et al. Psychiatric disorders among patients seeking treatment for co-occurring chronic pain and opioid use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(10):1413–1419. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boscarino JA, Rukstalis M, Hoffman SN, et al. Risk factors for drug dependence among out-patients on opioid therapy in a large US health-care system. Addiction. 2010;105:1776–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Injury Surveillance Workgroup. Consensus recommendations for national and state poisoning surveillance. Atlanta, GA: The Safe States Alliance; 2012. www.safestates.org/resource/resmgr/imported/ISW7%20Full%20Report_3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson AB, Gladden RM, Delcher C, Spies E, et al. Increases in fentanyl-related overdose deaths - Florida and Ohio, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):844–849. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.