Abstract

Individuals with bipolar spectrum disorder (BSD) frequently meet criteria for comorbid anxiety disorders, and anxiety may be an important factor in the etiology and course of BSDs. The current study examined the association of lifetime anxiety disorders with prospective manic/hypomanic versus major depressive episodes. Participants were 244 young adults (aged 17–26) with milder forms of BSDs (i.e., bipolar-II, cyclothymia, BD-NOS). First, bivariate analyses assessed differences in baseline clinical characteristics between participants with and without DSM-IV anxiety diagnoses. Second, negative binomial regression analyses tested whether lifetime anxiety predicted number of manic/hypomanic or major depressive episodes developed during the study. Third, survival analyses evaluated whether lifetime anxiety predicted time to onset of manic/hypomanic and major depressive episodes. Results indicated that anxiety history was associated with greater illness severity at baseline. Over follow-up, anxiety history predicted fewer manic/hypomanic episodes, but did not predict number of major depressive episodes. Anxiety history also was associated with longer time to onset of manic/hypomanic episodes, but shorter time to onset of depressive episodes. Findings corroborate past studies implicating anxiety disorders as salient influences on the course of BSDs. Moreover, results extend prior research by indicating that anxiety disorders may be linked with reduced manic/hypomanic phases of illness.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, comorbidity, depression, hypomania, mood disorders

1. Introduction

Bipolar disorder has long been recognized as an impairing clinical condition, but more recently, increased interest has emerged in exploring the concept of a bipolar disorder spectrum that incorporates milder bipolar conditions (e.g., cyclothymia and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified) along a continuum with bipolar II and bipolar I disorders (Dunner, 2003; Katzow et al., 2003). Research on these conditions indicates that bipolar spectrum disorders (BSDs) are chronic disorders characterized by high rates of relapse and recurrence (Harrow et al., 1990). Individuals with BSDs experience substantial functional impairment, even when receiving treatment (Judd et al., 2003; Judd et al., 2005). BSDs also carry great socioeconomic impact (Begley et al., 2001) and represent a leading cause of disability (Ferrari et al., 2016). Advancing knowledge of the potential factors influencing BSD course and persistence has the potential to curtail the adverse trajectories of these disorders, as well as to decrease the cost and burden to society.

One factor that may be important to consider is comorbidity. Individuals with BSDs frequently meet criteria for other, co-occurring psychiatric disorders, with anxiety disorders being among the most common (Merikangas et al., 2007). Epidemiological studies estimate that 46–75% of individuals with BSDs have had at least one lifetime anxiety diagnosis (Merikangas et al., 2007; Sala et al., 2012; Simon et al., 2004). Several conceptual models of comorbidity between anxiety disorders and BSDs have been proposed. One model suggests that anxiety disorders and BSDs are pathophysiologically distinct phenomena that overlap by chance due to their commonality; another suggests that they are separate disorders but have overlapping etiological mechanisms or risk factors (e.g., affective dysregulation, approach sensitivity, shared underlying affective temperaments) (Chen and Dilsaver, 1995; Freeman et al,, 2002; McIntyre et al., 2006; Serafini et al., 2017). Yet another model suggests that anxiety is part of the etiology of BSDs, in that it serves as a reliable prodrome to developing BSDs and often manifests many years earlier than mood symptoms (Duffy et al., 2013). Indeed, research implicates anxiety as a frequent precursor to developing BSDs (Brückl et al., 2007; Goldstein and Levitt, 2007; Henin et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2000; Jolin et al., 2008). Additionally, two independent prospective studies showed that childhood anxiety disorders were associated with an increased (2.1- to 2.6-fold) risk for later mood disorders in offspring of parents with BSDs (Duffy et al., 2013; Nurnberger et al., 2011).

Unfortunately, anxiety disorder comorbidity is also linked with greater BSD severity (e.g., suicide risk, mental health service use, and hospitalization), chronicity, poorer treatment outcomes, and impaired psychosocial functioning (Gaudiano and Miller, 2005; Goldstein and Levitt, 2008; Otto et al., 2006; Sala et al., 2014; Simon et al., 2004). In fact, anxiety disorders are shown to uniquely predict BSD severity independently of other common comorbidities such as substance use disorders (Goldstein and Levitt, 2008; Simon et al., 2004).

Taken together, the above research underscores the significance of anxiety in both the onset and course of BSDs. The strength of the anxiety/BSD relationship has led to the addition of a new “anxious distress” diagnostic specifier for bipolar disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), fifth edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). What is less clear is whether anxiety is associated more consistently with the persistence and severity of certain phases of the illness (Vazquez et al., 2014). Some research to date suggests more reliable links between anxiety and depressive phases (e.g., severity, persistence) than between anxiety and manic phases of BSDs (Coryell et al., 2012; Gaudiano and Miller, 2005; O’Garro-Moore et al., 2015; Otto et al., 2006). However, contrary evidence suggests that anxiety is associated similarly with both mood poles of BSDs (depression and mania/hypomania) (Sala et al., 2012). These discrepancies in the literature may be due to the fact that most studies have recruited participants from treatment facilities, which may represent a more severe population. In addition to the likelihood that such participants may not be representative of all individuals with bipolar conditions (e.g., those with bipolar II disorder or cyclothymia), it may be difficult to temporally disentangle risk mechanisms due to confounding effects of treatment. Past studies have been limited by cross-sectional or retrospective designs and have not examined progression of the illness. A better understanding of the relationship between anxiety comorbidity and the phases of BSDs might elucidate both the nosologic and clinical relationship between anxiety disorders and BSDs.

The current study examined cross-sectional and prospective associations of lifetime anxiety disorder history with BSD course among individuals with bipolar II disorder (BD-II), cyclothymia, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BD-NOS). In the BSD sample, we first compared baseline differences in clinical characteristics among individuals with lifetime anxiety versus those without lifetime anxiety. Participants were judged to have lifetime anxiety if they met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder (agoraphobia, panic disorder, PTSD, GAD, specific phobia, social phobia, or OCD) at baseline or at any previous time in their lives. We hypothesized that anxiety history would be associated with greater BSD severity (e.g., suicidal ideation, younger age of onset, etc.). Second, we examined the relationship between lifetime anxiety and BSD episodes over the course of the study. We expected that anxiety history would be associated with a greater number of prospective depressive but not manic/hypomanic episodes. Third, we examined the association between lifetime anxiety and time to episode onset, with the hypothesis that anxiety history would be associated with shorter time to prospective depressive but not manic/hypomanic episodes.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedures

The study design was reviewed by an appropriate ethical committee (Temple University IRB); the study was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the declaration of Helsinki. All participants completed informed consent after the nature of the procedures had been fully explained. Participants were 244 undergraduate students enrolled in the Longitudinal Investigation of Bipolar Spectrum Disorders (LIBS) Project at Temple University (48%) and the University of Wisconsin (52%) (Alloy et al., 2008; Alloy et al., 2012). For the LIBS Project, students were screened over the course of four years in two separate phases. Phase I encompassed screening of 20,543 students across the two sites utilizing a self-report measure of depressive and manic symptom severity, the General Behavior Inventory (GBI) (Depue et al., 1989). In Phase II, based on GBI cutoffs (see Measures), 1730 potentially eligible students completed the expanded SADS-L (see Measures) for screening. At a baseline visit following Phase I and II, participants eligible for the longitudinal study completed measures of depression symptom severity and hypo/manic symptom severity. All participants in the final sample met DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and/or Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (Spitzer et al., 1978) criteria for BD-II disorder or cyclothymia, or met project-defined criteria for bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BD-NOS).1 A goal of the larger LIBS Project was to determine risk factors for bipolar I disorder (BD-I) onset, and therefore, individuals were excluded if they reported a DSM-IV or RDC manic episode at baseline (Alloy et al., 2012). However, individuals who eventually developed BD-I over the course of the study were not excluded, because one aim of the current study was to examine the effects of anxiety on time to onset of future hypo/mania episodes. Follow-up diagnostic assessments occurred approximately every 4 months (months in study = 43.45, SD = 32.24). The attrition rate in the LIBS Project was 10.71% of BSD and control participants across both sites (Alloy et al., 2012). Of the participants who attrited, 71.11% dropped out after the first or second follow-up timepoint, 22.22% dropped out after the third or fourth follow-up timepoint, and 6.67% dropped out following the fifth timepoint. The majority of participants who dropped out did so because they were unable to meet the required time commitment, and some participants (7.91%) also left the study because they dropped out, transferred, graduated from college, or moved out of the area.

The final sample (N = 244) was 58% female, aged 17–26 years (M = 20.49, SD = 1.74 years). At baseline, 66 participants had cyclothymia or BD-NOS (27.04%) and 178 participants had BD-II (72.96%). Almost half (47.2%) reported a history of outpatient psychiatric treatment (28.2% received medication, 42.3% received psychotherapy), and 1.8% reported psychiatric hospitalization. One hundred and eight (68.40%) participants in the sample had a positive family history of mood disorders among first-degree relatives.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

(Beck et al., 1979) assessed the presence and severity of current symptoms of depression. The BDI has been shown to be valid among student samples (Bumberry et al., 1978; Hammen, 1980). It was administered at baseline (α = 0.94).

2.2.2 The Halberstadt Mania Inventory (HMI)

(Halberstadt and Abramson, 2007) measured current cognitive, motivational, affective and somatic symptoms associated with mania/hypomania. The HMI was modeled after the BDI and is administered and scored in a similar manner. In prior studies, the HMI has shown high internal consistency (α = 0.82), adequate convergent validity (r = 0.32) with the mania scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) (Hathaway and McKinley, 1943) as well as discriminant validity in a group of 1,282 undergraduate students (Halberstadt and Abramson, 2007). Alloy and colleagues (1999) also provided evidence of the construct validity of the HMI. The HMI was administered at baseline (α = 0.83).

2.2.3 The General Behavior Inventory (GBI)

(Depue et al., 1989), a 73-item self-report questionnaire assessing presence and severity of hypo/manic and depressive symptoms, was used in the Phase I screening to identify potential BSD participants. The following cutoff scores were used to identify potential BSD participants: a GBI depression subscale score of ≥ 11 and a GBI (hypo)mania/biphasic subscale score of ≥ 13 (Depue et al., 1989). The GBI has been validated among many populations (e.g., undergraduates, relatives of BD-I probands, psychiatric outpatients) and has strong psychometric properties (Depue et al., 1989; Klein et al., 1985).

2.2.4 The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Lifetime version (SADS-L)

(Endicott and Spitzer, 1978), a semi-structured diagnostic interview, was administered at baseline. Modifications for use in the LIBS study included: (a) added probes to allow the assignment of both DSM-IV and RDC diagnoses; (b) added items to better capture acute characteristics of episodes, frequency, and duration of symptoms; and (c) additional sections probing for other psychopathology (e.g., eating disorders) and medical/family history (Alloy et al., 2008; Alloy et al., 2012). Extensively trained doctoral and bachelor-level interviewers conducted the interviews. Inter-rater reliability was strong (kappa = 0.96) for BSDs (Alloy et al., 2008).

2.2.5 The Schedule for Affective Disorders – Change version (SADS-C)

(Alloy et al., 2012) was administered at all follow-up assessments to diagnose DSM-IV and RDC episodes of depression and mania/hypomania (see also: Alloy et al., 2008; Alloy et al., 2012; Francis-Raniere et al., 2006). The SADS-C is a semi-structured interview that assesses duration, timing, and severity of symptoms for various DSM-IV and RDC mood, anxiety, psychotic, and substance use disorders since the last interview. Inter-rater reliability for the SADS-C was strong (kappa = 0.80) (Francis-Raniere et al., 2006). The following variables were included in the current analyses: (1) any DSM-IV or RDC manic/hypomanic episode, and (2) any DSM-IV or RDC major depressive episode. See Alloy et al. (2008) for more details about the reliability and validity of the SADS-L and SADS-C in the LIBS project.

2.3 Data Analytic Strategy

Our data analytic strategy consisted of three main sets of analyses. First, we used t-tests and Chi-square analyses to examine baseline clinical differences in BSD participants with versus without a history of anxiety. Second, we used negative binomial regression to test presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder as a predictor of the number of hypomanic/manic and depressive episodes developed over the course of the study. Finally, we used Cox proportional hazard regression (survival) analyses to evaluate presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder as a predictor of time to onset of mood episodes.

For the second set of analyses, we selected negative binomial regression because it is an ideal analysis technique for logistic regression with a count outcome variable, assuming that overdispersion (i.e., individual counts are more variable than would be implied or expected by the model) is present in the data (Gardner et al., 1995). We chose to use the negative binomial regression analysis method after examining the conditional variances and conditional means of our outcome variables of interest at the two levels of our predictor (absence or presence of history of lifetime anxiety disorder). Given that the conditional variances were higher than the conditional means at both levels of “lifetime anxiety disorder”, overdispersion is likely present in the data, and negative binomial regression is preferable to Poisson regression (Gardner et al., 1995). Negative binomial regression analyses are detailed in the results section.

For the third set of analyses, we sought to understand the relationship between lifetime anxiety and the time course of depressive and hypo/manic episodes during the study. We selected Cox proportional hazard regression as an analysis technique because it is an ideal analysis method for our dataset given its ability to accommodate varying follow-up lengths and variable interval times between visits, utilize all available data at each time point, reduce biases due to attrition of participants, and allow for the presence of right-censored cases, in the form of participants who leave the study before onset of a mood episode or participants who do not experience onset of a mood episode over the course of follow-up (Willett and Singer, 1993). Analyses are detailed in the results section below.

3. Results

3.1. Lifetime anxiety diagnoses

Table 1 shows the prevalence of lifetime anxiety diagnoses among participants at baseline. Ninety-three (39.10%) met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a lifetime anxiety disorder (agoraphobia, panic disorder, PTSD, GAD, specific phobia, social phobia, or OCD). Among those with lifetime anxiety, most met criteria for one (66.66%) or two (20.43%) diagnoses.

Table 1.

Lifetime Anxiety Disorder Prevalence at Baseline

| Presence of Lifetime Diagnosis | % |

|---|---|

| Agoraphobia | 2.8 |

| Panic disorder | 6.4 |

| PTSD | 13.2 |

| GAD | 9.8 |

| Specific phobia | 13.7 |

| Social phobia | 10.0 |

| OCD | 6.8 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 39.1 |

|

| |

| Number of Lifetime Diagnoses (Range 1–5, M = 1.5) | % |

|

| |

| 1 anxiety disorder | 66.7 |

| 2 anxiety disorders | 20.4 |

| 3 anxiety disorders | 9.7 |

| More than 3 anxiety disorders | 3.3 |

3.2. Depressive and (hypo)mania episode characteristics

Twenty-four participants (9.8%) in the sample experienced a DSM-IV or RDC major depressive episode during the course of the study, whereas 144 participants (59.0%) experienced a DSM-IV or RDC hypomanic or manic episode during the course of follow-up. Participants experienced an average of 11.28 (SD = 12.14) DSM-IV or RDC hypomanic or manic episodes during the follow-up period and 0.85 (SD = 1.38) DSM-IV or RDC major depressive episodes during the follow-up period. Of the participants who experienced a major depressive episode, their average number of days to first onset of an episode was M = 1031.38 (SD = 531.73); among those who experienced a (hypo)manic episode during follow-up, the average number of days to first onset was 522.69 (SD = 528.28).

3.3. Baseline clinical differences in BSD participants with versus without a history of anxiety

We first examined differences in baseline clinical characteristics of participants with a history of anxiety disorder (anxiety group) and without a history of anxiety disorder (non-anxiety group). Independent samples t-tests and Chi-squared analyses compared the groups on the following variables: lifetime substance use disorder, age of onset of first hypomanic episode, age of onset of first depressive episode, history of outpatient psychiatric treatment, history of psychiatric medication use, suicidal ideation (collected in the depression section of the exp-SADS-L and coded as present or absent), family history of mood disorder, BDI scores, and HMI scores (see Table 2). Participants in the anxiety group had a significantly higher chance of a lifetime substance use disorder (χ2 = 5.34, df = 1, p = 0.02) and higher BDI scores (t = −2.23, p = 0.03) compared to those in the non-anxiety group. The anxiety and non-anxiety groups did not significantly differ at baseline on suicidal ideation, family history of mood disorder, history of outpatient therapy, psychiatric medication use, age of onset of first depressive or hypomanic episode, or HMI scores. Overall, when compared to the non-anxiety group, the anxiety group exhibited baseline clinical characteristics associated with higher severity of illness and poorer prognosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

T Tests and Chi-square Analyses Comparing Individuals with versus without Lifetime Anxiety Disorders at Baseline

| Full Sample | Anxiety History | No Anxiety History | Effect Sizes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclothymia (vs. Bipolar II) | 27% | 24% | 30% | <0.01 |

| Suicidal ideation | 43% | 48% | 38% | <0.01 |

| Lifetime substance use disorder | 28% | 37% | 23%* | 0.02 |

| Family history of mood disorder | 68% | 70% | 65% | <0.01 |

| Outpatient treatment | 42% | 49% | 38% | 0.01 |

| Psychiatric medication | 28% | 35% | 23% | 0.02 |

| Onset age hypomania (years) – M(SD) | 15(5) | 15(5) | 15(5) | 0.05 |

| Onset age depression (years) – M(SD) | 18(4) | 18(4) | 18(4) | 0.03 |

| Depressive symptoms – M(SD) | 10(10) | 12(12) | 9(9)* | 0.31 |

| Hypomanic symptoms – M ± SD | 14 ± 9 | 14 ± 9 | 14 ± 9 | 0.05 |

Anxiety groups differed at the p < 0.05 level,

Effect sizes correspond to Cohen’s d and Cramer’s V.

3.4. Lifetime anxiety and prospective number of mood episodes

We next examined the relationship between a lifetime anxiety disorder history and the prospective course of BSDs. In all analyses, baseline BDI and HMI scores were entered as covariates to control for effects of baseline mood symptoms on developing a mood episode. Number of days in the study also was entered as a covariate to control for the effect of amount of time in developing a mood episode. Treatment seeking for mood problems (outpatient treatment or psychiatric medications) during follow-up (yes/no) also was entered as a covariate to control for the possibility that treatment might alter development of mood episodes. Family history of mood disorders was included as a covariate to control for familial effects. Alcohol and substance dependence were entered as covariates to account for any effects of substance use on development of mood episodes (Ostacher et al., 2010).

We performed negative binomial regression to test whether the presence of a lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder predicted the number of prospective manic/hypomanic episodes or major depressive episodes developed by participants over the course of the study. Negative binomial regression was run for two separate models; both models included presence/absence of lifetime anxiety (presence = 1, absence = 0) as a dichotomous predictor, and both models also included the additional covariates specified above. The first model specified number of hypomanic/manic episodes as the outcome variable and the second model specified number of major depressive episodes as the outcome variable. A positive anxiety history predicted fewer episodes of mania/hypomania over the course of the study, such that there was a 58% decrease in the incident rate of manic/hypomanic episodes for those who have a history of lifetime anxiety (Wald = 4.23, Exp(B) = 0.58, p = 0.04). Presence of a lifetime history of anxiety was not, however, a significant predictor of the incident rate of major depressive episodes developed over the course of the study (Wald = .148, Exp(B) = 1.15, p = 0.70).

3.5. Lifetime anxiety and time to onset of depression and mania/hypomania

Finally, Cox proportional hazard regression (survival) analyses were used to evaluate the relationship between lifetime anxiety and time to onset of mood episodes. First, we tested the proportionality of hazards assumption for the Cox regression. We tested this assumption by examining the interaction of time with each of our covariates (BDI score at baseline, HMI score at baseline, alcohol and substance dependence, number of days in the study, and treatment history). None of these interactions was significant for either of our two Cox regression models; thus, the proportionality of hazards assumption was met.

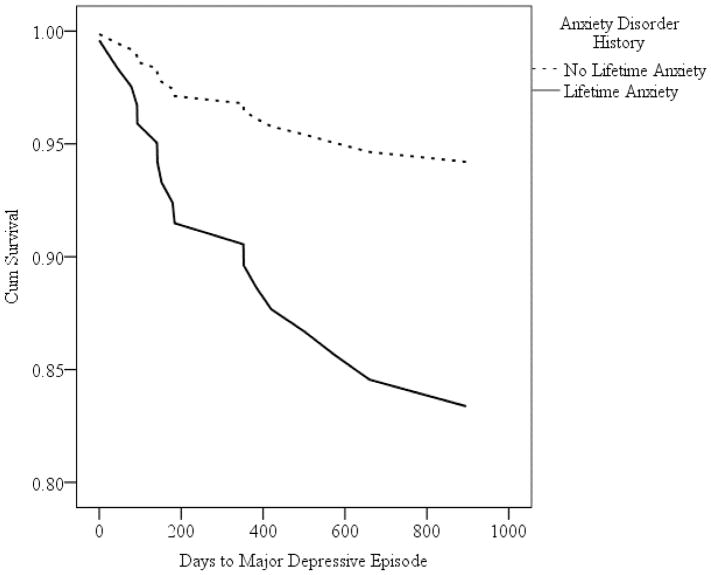

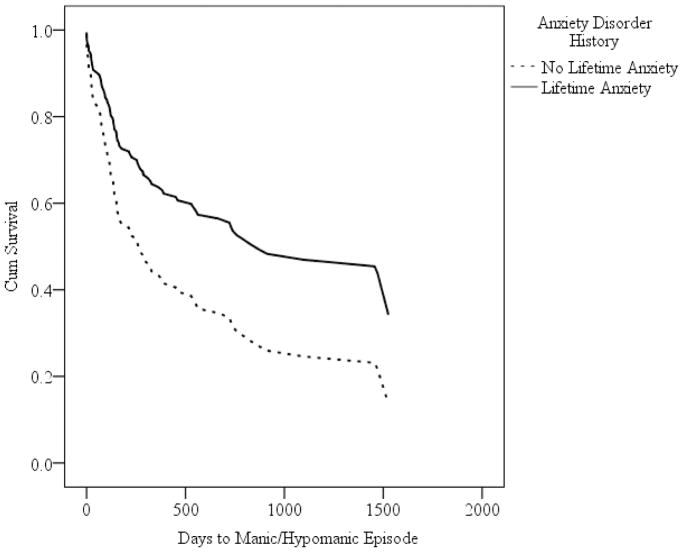

In two separate models, we entered presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder (yes = 1, no = 0) as the independent variable and time to onset of a mood episode as the dependent variable. Controlling for the covariates (described above), anxiety history predicted shorter time to onset of major depressive episodes (Wald = 4.08, p = 0.04, HR = 3.05), such that the incidence (hazard) rate for developing a major depressive episode was over 3 times greater for participants with anxiety history than without anxiety history. Anxiety history also predicted longer time to onset of manic/hypomanic episodes (Wald = 6.77, p = 0.009, HR = 0.54), such that the incidence (hazard) rate for developing a manic/hypomanic episode was 46% smaller for participants with anxiety history than without anxiety history. Survival curves for time to onset of major depressive episodes and manic/hypomanic episodes are presented in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Survival Curves for Cox Regression Analyses Predicting Time to Major Depressive Episode

Figure 2.

Survival Curves for Cox Regression Analyses Predicting Time to Manic or Hypomanic Episode

4. Discussion

Results of the present study indicate, first, that among individuals with BSDs, history of anxiety disorder was associated with greater likelihood of substance use disorder and greater self-reported depressive symptomatology. Second, anxiety disorder history predicted a shorter time to prospectively developing a major depressive episode, but not a greater number of major depressive episodes over follow-up. Third, anxiety disorder history was associated with longer time to onset of manic/hypomanic episodes and fewer manic/hypomanic episodes over the course of follow-up. Our findings partially support past research showing that history of anxiety disorders is associated with depressive phases of the illness (Simon et al., 2007), but are unique in that, to our knowledge, they are the first to show an inverse relationship between anxiety history and mania/hypomania. Previous empirical findings examining the association between anxiety comorbidity and mania/hypomania have been equivocal. González-Pinto and colleagues (2012) demonstrated that among bipolar I inpatients, anxiety symptoms were associated with exacerbated manic symptoms. Conversely, Saunders and colleagues (2012) found no significant relationship between anxiety and severity/number of manic episodes; Magalhães and colleagues (2010) reported no association between the presence of OCD and manic symptoms. However, it is important to note that these studies evaluated samples with severe symptomatology, whereas we examined these relationships in individuals who, at baseline, had diagnoses of BD-II, cyclothymia, and BD-NOS, with low rates of hospitalization. The relationships observed in our study may be specific to individuals with less severe psychopathology.

We suggest three possibilities for why anxiety history might be inversely related to mania/hypomania in our sample. First, lifetime anxiety may mitigate the tendency to develop manic/hypomanic symptoms by dampening the expression and/or severity of certain symptoms. Perugi and colleagues (2001) proposed a model implicating temperament as a critical factor determining bipolar symptomatology. Specifically, they suggested that individuals range on temperamental dimensions. Depending on which end of the spectrum an individual falls (constrained versus disinhibited), he or she may be more likely to espouse symptoms that mimic anxiety or mania/hypomania, respectively. Thus, it is possible that individuals with comorbid anxiety and BSD exhibit a more constrained temperament and consequently are less likely to develop the cluster of symptoms that individuals with mania/hypomania exhibit (e.g., elevated energy, racing thoughts, decreased need for sleep). This hypothesis has been substantiated by Azorin and colleagues (2015), who found that BSD individuals with a predominantly manic/hypomanic course were more likely to have a hyperthymic temperament and less likely to have a comorbid anxiety disorder than those with a predominantly depressive course. These results suggest that depression and anxiety cluster together on temperamental dimensions.

A second, related explanation is that, because prior research suggests that BSD-anxiety comorbidity engenders a more chronically depressive course of BSD, individuals may spend more time in depressive phases of the illness, and therefore, have less opportunity to experience manic/hypomanic episodes. Although anxiety disorder comorbidity was not associated with a greater number of depressive episodes in our study, participants with a history of anxiety may have experienced more protracted episodes. Various studies indeed have found that the anxiety-BSD association typically coincides with more severe and longer episodes of depression (Lee and Dunner, 2008; Simon et al., 2004; Simon et al., 2007). Additionally, the presence of an anxiety disorder has been associated with less time spent euthymic (Boylan et al., 2004). Otto and colleagues (2006) found that comorbid anxiety predicted a worse course of bipolar disorder, (e.g., lower likelihood of recovery and high risk of relapse into depression). Taken together, these findings support the notion that lifetime anxiety may affect the course of BSD by invoking more chronic depressed states, allowing less opportunity to cycle into a manic/hypomanic state.

A third explanation may be related to the behavioral activation system (BAS) or the behavioral inhibition system (BIS) (Carver and White, 1994). Activation of the BAS, a biopsychosocial system that controls approach motivation in the presence of appetitive stimuli, has been shown to be associated with happiness and elevated energy (Johnson et al., 2003) and with the presence of hypomania/mania (Alloy et al., 2015). Hypersensitivity of this system has been used to explain the etiology and course of BSDs (Alloy et al., 2008; Alloy et al., 2015; Sala et al., 2012; Urosevic et al., 2008). The BAS can be up-regulated (more responsiveness of the reward system, related to mania/hypomania) or down-regulated (less responsiveness to reward, related to depression). Individuals with BSDs are hypersensitive to both of these dysregulation pathways. Hypersensitivity of the BAS may result in up-regulation of BAS activity when an individual encounters a reward relevant stimulus or life event, triggering manic/hypomanic symptoms. When a goal is not met or reward is not obtained, severe rebounding and hypo-activation occurs, engendering depressive symptoms. Adapting this theory to our findings, it may be that individuals with lifetime anxiety experience more down-regulation of the BAS due to a shared mechanism between BSDs and anxiety. In support of this, past research has shown BAS activity to be inversely associated with anxiety disorders (Kimbrel et al., 2010).

The Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) also has been implicated in anxiety and depression. Contrary to the BAS, the BIS controls withdrawal behavior, and activates when in the presence of threatening stimuli or punishment (Carver and White, 1994). Among BSD individuals, the BIS system is postulated to be hypersensitive, engendering depressive episodes or anxious behavior. Consistent with this, self-reported BIS sensitivity has been associated with Rottenberg, Arnow, and Gotlib, 2002; Pinto-Meza et al., 2006). Given that BIS is also linked with anxiety (Rosenbaum et al., 1993), hypersensitivity of the BIS system may represent another explanation of why lifetime anxiety would predict a more depressive, rather than manic, course of illness.

Among the strengths of this study were the relatively large sample size, the inclusion of a large number of covariates, and the prediction of prospective mood episodes. Moreover, this study was unique in that it did not solely rely upon cross-sectional data, a limitation of many previous studies. These features allowed us to adequately examine the progression of anxiety and BSD over an extended period of time.

Despite the strengths of the study, it was not without several limitations. First, in creating our ‘Anxiety Disorders’ category, as has been done in prior studies (e.g., O’Garro-Moore et al., 2015; Simon et al., 2007), we grouped all DSM-IV anxiety diagnoses together. Different anxiety disorders may have different patterns of association with BSD course (Perugi et al., 2001). Similarly, certain anxiety symptoms (e.g., psychic and somatic) may be particularly important, as they may have differential effects on the BSD course. Furthermore, we did not assess anxiety severity or the impact of sub-syndromal anxiety. Dimensional measures would better capture the range of anxiety severity as well as allow for a more holistic description of the association between anxiety and BSDs. It is also important to note that participants in our study were experiencing more “soft” features of bipolar disorder, and it is not clear whether findings would generalize to all BSD samples.

The findings of the present study suggest that a history of anxiety disorder may promote depressive phases of BSDs, while at the same time protecting against hypomanic/manic phases. If replicated, the current findings may increase our understanding of factors influencing BSD course. For instance, the presence of anxiety history comorbidity with a BSD may aid researchers and clinicians in more accurately identifying a likely future course of BSD illness. Replication of our findings may also help inform better treatment; clinicians might anticipate that anxiety preceding a BSD signals the likelihood of a more depressive and less (hypo)manic course, and they could alter their treatment targets to more strongly address the depression. Future research should also focus on elucidating anxiety-related factors (e.g., shared affective temperamental dimensions) that promote shorter time to onsets of depressive episodes and longer time to onsets of and fewer manic/hypomanic episodes in BSD. Individuals with BSDs spend substantially more time depressed than manic/hypomanic (Solomon et al., 2010), and depression accounts for most of the morbidity and mortality associated with BSDs (Bauer et al., 2001; Mitchell and Malhi, 2004; Rosa et al., 2010). From a clinical standpoint, we should seek to accurately identify the anxiety-related factors that increase potential for longer and more severe depressive phases in order to prevent these factors from negatively influencing the course of the illness.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Lifetime anxiety comorbidity in bipolar spectrum disorders was examined.

Main analyses consisted of negative binomial regression and Cox regression.

Anxiety history was associated with greater illness severity at baseline.

Anxiety history predicted a greater likelihood of prospective major depression.

Anxiety history predicted a lesser likelihood of prospective (hypo)mania.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health [Grant numbers MH52617, MH77908, MH52662].

Role of the Funding sources: Funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

The BD-NOS group comprised individuals who had experienced three types of symptoms: (a) hypomanic episode(s) but no diagnosable depressive episodes, (b) a cyclothymic mood pattern with periods of affective disturbance that did not meet frequency/duration criteria for hypomanic and depressive episodes, or (c) hypomanic and depressive episodes not meeting frequency criteria for a diagnosis of cyclothymia.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Cogswell A, Grandin LD, Hughes ME, et al. Behavioral approach system and behavioral inhibition system sensitivities and bipolar spectrum disorders: prospective prediction of bipolar mood episodes. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:310–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Nusslock R, Boland EM. The development and course of bipolar spectrum disorders: an integrated reward and circadian rhythm dysregulation model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2015;11:213–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Reilly-Harrington N, Fresco DM, Whitehouse WG, Zechmeister JS. Cognitive styles and life events in subsyndromal unipolar and bipolar disorders: Stability and prospective prediction of depressive and hypomanic mood swings. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1999;13:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Urošević S, Abramson LY, Jager-Hyman S, Nusslock R, Whitehouse WG, et al. Progression along the bipolar spectrum: A longitudinal study of predictors of conversion from bipolar spectrum conditions to bipolar I and II disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:16–27. doi: 10.1037/a0023973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association, editor. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association, editor. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Azorin JM, Adida M, Belzeaux R. Predominant polarity in bipolar disorders: Further evidence for the role of affective temperaments. J of Affective Disord. 2015;182:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Kirk GF, Gavin C, Williford WO. Determinants of functional outcome and healthcare costs in bipolar disorder: a high-intensity follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2001;65:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, editors. The Guilford Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy Series. Guilford Press; New York: 1979. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. 13. print. ed. [Google Scholar]

- Begley CE, Annegers JF, Swann AC, Lewis C, Coan S, Schnapp WB, et al. The lifetime cost of bipolar disorder in the US: an estimate for new cases in 1998. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:483–495. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan KR, Bieling PJ, Marriott M, Begin H, Young LT, MacQueen GM. Impact of comorbid anxiety disorders on outcome in a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1106–1113. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brückl TM, Wittchen HU, Höfler M, Pfister H, Schneider S, Lieb R. Childhood separation anxiety and the risk of subsequent psychopathology: Results from a community study. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:47–56. doi: 10.1159/000096364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumberry W, Oliver JM, McClure JN. Validation of the Beck Depression Inventory in a university population using psychiatric estimate as the criterion. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Comorbidity of panic disorder in bipolar illness: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:280. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Fiedorowicz JG, Solomon D, Leon AC, Rice JP, Keller MB. Effects of anxiety on the long-term course of depressive disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200:210–215. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue R, Krauss S, Spoont M, Arbisi P. General Behavior Inventory identification of unipolar and bipolar affective conditions in a nonclinical university population. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:117–126. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, Keown-Stoneman C, McCloskey S, Grof P. Childhood anxiety: An early predictor of mood disorders in offspring of bipolar parents. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunner D. Clinical consequences of under-recognized bipolar spectrum disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:456–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-5618.2003.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari AJ, Stockings E, Khoo J-P, Erskine HE, Degenhardt L, Vos T, et al. The prevalence and burden of bipolar disorder: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18:440–450. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-Raniere EL, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Depressive personality styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: prospective tests of the event congruency hypothesis. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:382–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano BA, Miller IW. Anxiety disorder comobidity in Bipolar I Disorder: Relationship to depression severity and treatment outcome. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;21:71–77. doi: 10.1002/da.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Levitt AJ. The specific burden of comorbid anxiety disorders and of substance use disorders in bipolar I disorder: Anxiety and substance use disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Levitt AJ. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar I disorder among adults with primary youth- onset anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;103:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Pinto A, Galán J, Martín-Carrasco M, Ballesteros J, Maurino J, Vieta E. Anxiety as a marker of severity in acute mania: Anxiety in Mania. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;126:351–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt LJ, Abramson LY. The Halberstadt Mania Inventory (HMI): A self-report measure of manic/hypomanic symptomatology 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Hammen CL. Depression in college students: beyond the Beck Depression Inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1980;48:126–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Goldberg JF, Grossman LS, Meltzer HY. Outcome in manic disorders. A naturalistic follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:665–671. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810190065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. The Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, MN: 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Henin A, Biederman J, Mick E, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Sachs GS, Wu Y, et al. Childhood antecedent disorders to bipolar disorder in adults: A controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2007;99:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brook JS. Associations between bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders during adolescence and early adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1679–1681. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Turner RJ, Iwata N. BIS/BAS levels and psychiatric disorder: An epidemiological study. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2003;25:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jolin EM, Weller EB, Weller RW. Anxiety symptoms and syndromes in bipolar children and adolescents. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2008;10:123–129. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Maser J, et al. The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J Affect Disord. 2003;73:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA, et al. Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: A prospective, comparative, longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1322. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzow JJ, Hsu DJ, Ghaemi SN. The bipolar spectrum: A clinical perspective. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:436–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-5618.2003.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Mitchell JT, Nelson-Gray RO. An examination of the relationship between behavioral approach system (BAS) sensitivity and social interaction anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Depue RA, Slater JF. Cyclothymia in the adolescent offspring of parents with bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1985;94:115–127. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Dunner DL. The effect of anxiety disorder comorbidity on treatment resistant bipolar disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:91–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães PVS, Kapczinski NS, Kapczinski F. Correlates and impact of obsessive-compulsive comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2010;51:353–356. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Soczynska JK, Bottas A, Bordbar K, Konarski JZ, Kennedy SH. Anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:665–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RMA, Petukhova M, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:543. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PB, Malhi GS. Bipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristics. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:530–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI. A high-risk study of bipolar disorder: childhood clinical phenotypes as precursors of major mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:1012. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Garro-Moore JK, Adams AM, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Anxiety comorbidity in bipolar spectrum disorders: The mediational role of perfectionism in prospective depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostacher MJ, Perlis RH, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese J, Stange JP, Salloum I, et al. Impact of substance use disorders on recovery from episodes of depression in bipolar disorder patients: prospective data from the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:289–297. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Simon NM, Wisniewski SR, Miklowitz DJ, Kogan JN, Reilly-Harrington, et al. Prospective 12-month course of bipolar disorder in out-patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:20–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perugi G, Maremmani I, Toni C, Madaro D, Mata B, Akiskal HS. The contrasting influence of depressive and hyperthymic temperaments on psychometrically derived manic subtypes. Psychiatry Res. 2001;101:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa AR, Reinares M, Michalak EE, Bonnin CM, Sole B, Franco C, et al. Functional impairment and disability across mood dtates in bipolar disorder. Value in Health. 2010;13:984–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala R, Goldstein BI, Morcillo C, Liu SM, Castellanos M, Blanco C. Course of comorbid anxiety disorders among adults with bipolar disorder in the U.S. population. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala R, Strober MA, Axelson DA, Gill MK, Castro-Fornieles J, Goldstein TR, et al. Effects of comorbid anxiety disorders on the longitudinal course of pediatric bipolar disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders EFH, Fitzgerald KD, Zhang P, McInnis MG. Clinical features of bipolar disorder comorbid with anxiety disorders differ between men and women. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:739–746. doi: 10.1002/da.21932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini G, Geoffroy PA, Aguglia A, Adavastro G, Canepa G, Pomopili M. Irritable temperament and lifetime psychotic symptoms as predictors of anxiety symptoms in bipolar disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;72:63–71. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2017.1385851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data From the first 500 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222–2229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Zalta AK, Otto MW, Ostacher MJ, Fischmann D, Chow CW, et al. The association of comorbid anxiety disorders with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in outpatients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DA, Leon AC, Coryell WH, Endicott J, Li C, Fiedorowicz JG, Boyken L. Longitudinal course of bipolar I disorder: duration of mood episodes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:339. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urošević S, Abramson LY, Harmon-Jones E, Alloy LB. Dysregulation of the behavioral approach system (BAS) in bipolar spectrum disorders: Review of theory and evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1188–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez GH, Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L. Co-occurrence of anxiety and bipolar disorders: clinical and therapeutic overview. Depression and Anxiety. 2014;31:196–206. doi: 10.1002/da.22248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD. It’s deja vu all over again: Using multiple-spell discrete-time survival analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1995;20:41–67. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.