Abstract

This note highlights our understanding and thinking about the feasibility of l-asparaginase as therapeutics for multiple diseases. l-asparaginase enzyme (l-asparagine amidohydrolase, EC 3.5.1.1) is prominently known for its chemotherapeutic application. It is primarily used in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. It is also used in the treatment of other forms of cancer Hodgkin disease, lymphosarcoma, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, reticulosarcoma and melanosarcoma (Lopes et al. Crit Rev Biotechnol 23:1–18, 2015). It deaminates l-asparagine present in the plasma pool causing the demise of tumor cell due to nutritional starvation. The anti-tumorigenic property of this enzyme has been exploited for over four decades and evidenced as a boon for the cancer patients. Presently, the medical application of l-asparaginase is limited only in curing various forms of cancer.

Keywords: l-asparaginase, Malignance, Autoimmune disease, Infectious disease, Therapeutic

l-Asparaginase: single molecule for multiple outcomes

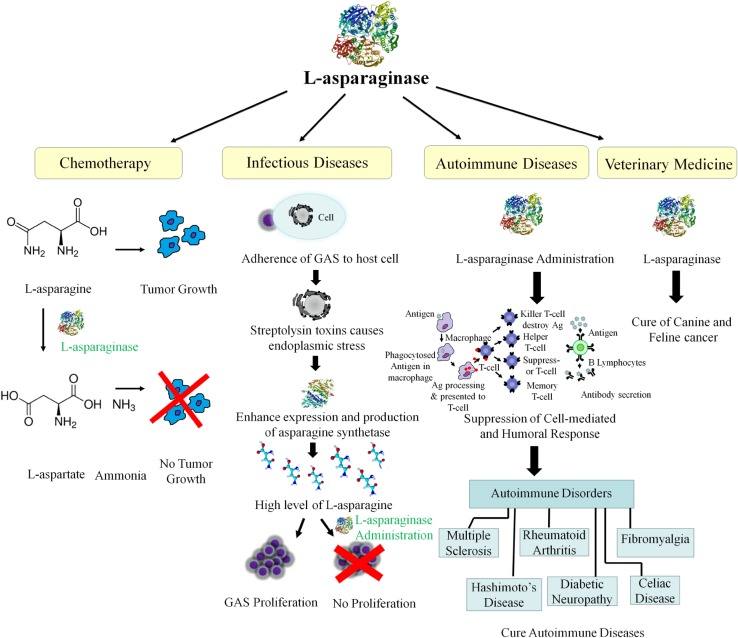

It is evident from the literature that the enzyme holds potential for more extensive applications in the treatment of other diseases apart from cancer (Fig. 1). One of such applicability is in the treatment of infectious diseases. Baruch et al. (2014a) finding take hold of metabolic changes that occur in the course of infection caused by a pathogen. This could be exploited for an efficient treatment of infectious diseases. Streptococcus pyogenes [Group A streptococcus (GAS)] is the causative agent of a wide variety of infectious diseases: Necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating disease), pharyngitis, glomerulonephritis, scarlet fever, toxic shock syndrome, meningitis, rheumatic fever. It was testified that L-asparaginase obstructs GAS proliferation in human blood and in a mouse model of bacterial infection. It was reported by Baruch et al. (2014b) that GAS induces UPR (unfolded protein response) to capture l-asparagine from the host. The infection mechanism initiates with the adherence of GAS to the host cell. Then it releases streptolysin toxins (streptolysin O and streptolysin S) that induce endoplasmic reticulum stressed condition. This situation accounts for the activation of PERK (PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase). The activated PERK phosphorylates the α-subunit of the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) and translation of ATF4 (activating transcription factor 4) occurs (Saito et al. 2011). This boosts the expression and production of asparagine synthetase which increases the concentration of l-asparagine in the medium. The liberated l-asparagine is then used by GAS for its growth and proliferation inside the host cell. Thus, the invasion mechanism is channelized through PERK-eIF2-ATF4 pathway. Here, comes the role of therapeutic L-asparaginase: check the propagation of GAS inside the host by mitigating l-asparagine from the medium. It is also presumed that infections caused by other Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium botulinum can also be treated by l-asparaginase. The reason is that they secrete similar streptolysin toxins and may also follow the same mechanism of multiplication in the host (Baruch et al. 2014a, b). Clostridium botulinum secretes a binary toxin, namely C2 toxin, that is composed of two subunits, C2I and C2II required for interaction with the mammalian cell. The binding of C2 toxin to the host cell depends on the presence of asparagine-linked carbohydrate (Eckhardt et al. 2000). The suggested cure for Clostridium botulinum mediated diseases is treatment with N (4)-(beta-N-acetylglucosaminyl)-l-asparaginase (AGA) which breakdowns the l-asparagine carbohydrate linkage and prevent its adherence to the host cell. Infection with F. tularensis is another reported example of l-asparagine mediated infectious diseases. The gram-negative bacterium uses l-asparagine for cytosolic multiplication through ΔansP transporter (Gesbert et al. 2014). l-asparaginase could also be a useful defense against this pathogen.

Fig. 1.

Application of l-asparaginase in the treatment of various diseases

Another acknowledgeable fact about l-asparaginase is its immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory property (Gieldanowski 1976). It has the ability to overcome T-cell-mediated B-cell responses. It is also reported to overpower the humoral and cell-mediated immunological response to T-cell dependent immunogens on sheep red blood cells (SRBCs). Along with this, it reduces splenic immunoglobulin producing B-cells. This immunosuppressive property could be used in the direction of developing medication for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (Reiff et al. 2001). An attempt was made in this direction by treating male DBA/1 mice having collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) with pegylated l-asparaginase from E. coli. It has been found that this enzyme has high efficacy and less toxicity as compared to cyclophosphamide in treating CIA (Reiff et al. 2001).

The therapeutic application of this medically valuable enzyme is not limited to human use. It also has veterinary use in the management of canine and feline lymphomas. It is a part of the multidrug curative protocol and is accompanied by Lomustine and prednisone (Saba et al. 2009). The reoccurrence of canine malignancy is often observed and requires scavenging therapy. It is because of acquiring of multidrug resistance (MDR). The accountable reasons of MDR are insufficient dosing, wrong frequency, or incorrect route of administration. The use of combination therapy delays the onset of MDR as different drugs have different mechanism. l-asparaginase is administered by the veterinary oncologist to prolong the duration of remission of a tumor, letting them time to search alternative curing therapies.

This enzyme holds potential effectiveness for a wide variety of therapeutic applications. However, its usage is limited due to high monetary costs and unexplored potency against other diseases. The estimated cost of ALL treatment using PEGylated l-asparaginase is $57,893 whereas treatment using Erwinia asparaginase is even more expensive i.e. $113,558 (Vimal and Kumar 2017). The imperative role of this enzyme as a chemotherapeutic agent is well established. Though, the less accredited medical applicability like curing of infectious disease and autoimmune disorder is still unexplored. These operative treatment suggestions are currently limited to laboratory scale research work. There is a need to extend the medical applicabilities of this enzyme for practical implementation and benefit more patients.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to National Institute of Technology, Raipur (CG), India for providing facility, space and resources for this work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Baruch M, Belotserkovsky I, Hertzog BB, et al. An extracellular bacterial pathogen modulates host metabolism to regulate its own sensing and proliferation. Cell. 2014;156:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch M, Hertzog BB, Ravins M, et al. Induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response constitutes a pathogenic strategy of group A streptococcus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt M, Barth H, Blo D, Aktories K. Binding of clostridium botulinum C2 toxin to asparagine-linked complex and hybrid carbohydrates. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2328–2334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesbert G, Ramond E, Rigard M, et al. Asparagine assimilation is critical for intracellular replication and dissemination of Francisella. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:434–449. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieldanowski J. Studies on the immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory action of L-asparaginase. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1976;24:243–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes AM, Oliveira-nascimento L, Ribeiro A, et al. Therapeutic l-asparaginase: upstream, downstream and beyond. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2015;23:1–18. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2015.1120705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiff A, Zastrow M, Sun BC, et al. Treatment of collagen induced arthritis in DBA/1 mice with L-asparaginase. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba CF, Hafeman SD, Vail DM, Thamm DH. Combination chemotherapy with continuous -asparaginase, lomustine, and prednisone for relapsed canine lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;23:1058–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Ochiai K, Kondo S, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress response mediated by the PERK-eIF2(alpha)-ATF4 pathway is involved in osteoblast differentiation induced by BMP2. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4809–4818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.152900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vimal A, Kumar A. In vitro screening and in silico validation revealed key microbes for higher production of significant therapeutic enzyme l-asparaginase. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2017;98:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]